8

GETTING BACKSTAGE AND ONSTAGE

____________

Steve Brown

Filmmaker/Grateful Dead Records production coordinator (1972–1978)

Bill Graham’s manager for Fillmore West and the Winterland, Gary Jackson, was a politico—and my brother-in-law. In 1972, he was contacted by Jane Fonda to help get her husband Tom Hayden’s campaign going, and they thought employing the Grateful Dead for an event of some sort was a good idea.

I go to pick up Jane Fonda at the St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco. I remember she was wearing a beige-colored jacket and skirt thing. We go to the Winterland, and the band was pre-soundcheck. I brought her in and took her backstage to meet the band and have her do her pitch to them. They were all really kind of dumbfounded by the whole thing. They’d been warned, but apparently they’d forgotten that this was going to happen. So it was kind of awkward, their a-political stance of not really doing things for politicians. It was definitely a shoe that wasn’t going to fit. I kind of felt sorry for Jane in a way, and it made me feel awkward, too. We were all cordial, everybody was nice, and they talked about some other stuff—Barbarella or something. A roadie brought that up, I think.

There are often strange things that happen backstage—not awkward moments as much as interesting moments like that. Dylan was always interesting. I’d run into him in a backstage room. I met him at the Kezar when he played the S.N.A.C.K Concert at Kezar (“Students Need Activities, Culture and Kicks”). I think it was 1975. I was twenty-eight. There were locker rooms that were part of the Kezar backstage area or whatever you want to call it. I went in there and there’s Dylan and Jerry, and I thought, “This is cool.” But I didn’t want to disturb them, so I walked out.

That same show, I was behind the stage, looking out from the back of the stage. Right then, I felt a sort of presence around me, and it was kind of a large presence. I looked around, and it’s Marlon Brando with his wife, Sacheen Littlefeather! And that was weird enough. But as I looked behind me, in a little corduroy jean jacket was Bob Dylan. I was sandwiched between Bob Dylan and Marlon Brando for just long enough to think I’d gone somewhere weird in my world, never to return. It was a Twilight Zone kind of moment. It was also strange because Bob’s a small guy, and Brando was in his plumpy years.

When I tell people about experiences I’ve had like that, it’s like, “Yeah, right.” I have a hard time telling them because I thought I’d hallucinated it! It’s like, did that really happen? Is this big old guy standing here with this woman really Marlon Brando? And of course it was. And Dylan? Just so quiet. You don’t want to say anything to him.

Some Dead shows, you’d get crazed audience members jumping onstage or trying to barge in backstage, and you’d have to deal with people who just weren’t their real selves. Or, if they were their real selves, you wouldn’t want them back there anyway!

John Popper

Blues Traveler singer/harmonicist

Blues Traveler has had a long relationship to the Dead because of our association with the Grahams—David and Bill. I met David playing at a Barnard gig back East. He saw us, liked us a lot, and figured he could manage us because he was getting out of school. So he told his dad about it, and Bill approached us. He had us opening for the Neville Brothers less than a week later. He flew us out to open for Lynyrd Skynyrd. At one point, they were making the Doors’ movie in San Francisco, Bill was producing it, they needed some musicians to be in it, so we got in the movie, in the park scene. The day we filmed, we also opened for Garcia that night. It was a really San Francisco-y gig. To be filmed in Golden Gate Park for the Doors movie and then go to the Warfield to open for Jerry Garcia—we were all freaking out! It was really cool. When we got to the Warfield, I think it was Jerry’s personal manager, Steve Parrish, who said, “Okay, boys. Now no metal tonight!”

We went and had a good set. We were very nervous. The guitar didn’t work when we started, so we had to start over again. But that was okay. Looking back, that was kind of entertaining. We just had a ball. I remember watching Garcia playing. This music was just sort of oozing out of him. He just kind of telegraphs music right into you. It was a great thing to see.

The next time I played with Jerry was when Bill died in the fall of 1991. Bill had always been trying to get the Dead and Blues Traveler together, but it never seemed to happen. I just wanted to go to Bill’s memorial and be a part of it any way I could. And David wanted me to be there, so I flew out for that. Garcia didn’t seem too keen on it, but he would do it for David. So David wanted me to meet Garcia. I’m at the festival, and David said, “I talked to Jerry, and you’re gonna sit in with the Dead.” I was torn because it was a sad day, but it was a cool thing that I was going to sit in with the Dead. I met other members of the Dead—Phil and Bobby, and they were all very nice.

David wanted Jerry and me to have some sort of dialogue, so he took me into Jerry’s tent backstage. When I got in, Jerry’s eating a hamburger, and I’m just standing there staring at the floor. All I could think of to say was, “I’m a flurry of emotion.” And Jerry said, “Me, too,” with a long sigh. That was about it. I think he started to get a little annoyed with me, and he said, “This song will be in D.” I said, “Okay,” and I just started fidgeting with this little telescope I had. I think he got amused by that. But I just really had nothing to say to this man, and here I was left in his tent! David left, and it was me and Jerry hanging out. And the only thing I said was, “I’m a flurry of emotion.” Eventually, David came back and got me.

I remember hearing a tape of Carlos Santana once, trying to sit in with the Dead, and Carlos gave up all his chops early, and the Dead just kind of made him run out of things to say musically. So, when I got up to play, the one thing that kept running through my mind was, “Don’t try and blow your wad. If you play impressively, you’re gonna look stupid.” So I really held back, and they really had fun.

Within the next week, we were opening for Garcia at Madison Square Garden. Apparently he told someone afterwards that we blew him away. It just seemed to me, without having ever really talked to the guy since, that after I demonstrated a little self-control, he decided that we—Blues Traveler—were okay. I’ve always got the feeling that they thought we were too … “metal” is the word they use. But I think we’re just younger. I think when they were younger, they hit a lot more spots when they were playing, especially on Lesh’s part. Phil Lesh used to go crazy.

Tom Constanten

Keyboardist for the Grateful Dead, composer

Playing with the Grateful Dead, when it worked, was wonderful—like music in general: when it works, it’s wonderful; when it doesn’t, it can be very sucky. I was a newcomer, yet I wasn’t. I’d known Jerry and Phil since they knew some of the other guys in the band. And it was only because of my being in the clutches of the Air Force that I hadn’t been with them before.

The technology of the time wouldn’t allow sufficient amplification of a keyboard to give me anything resembling a dynamic range so I could be at all expressive. I felt I was shouting, musically speaking, to be heard at all. You can’t be very expressive when you’re at the top of your lungs all the time. Also, I had no instrument at home to practice on. The only time I played was at the shows or the rehearsals, so I had to do a lot of thinking on my feet. The military doesn’t pay a lot, and there were at least two places that didn’t like the band’s credit rating well enough to let me buy a piano from them. The instrument consideration was one of the suckiest things.

Of course, in the studio, that wasn’t a problem. All multi-tracking. At that time in the studio, the Dead were learning what they were doing also. Everybody was making it up as we went along.

Every “Dark Star” we did at the Fillmore East was like there were angels or something who made things work for us. I think part of that had to do with the fact that when you played for the New York audience then, you knew they were critical. But when they’re approving, it gives you this incredible lift.

Jerry Miller

Moby Grape/Jerry Miller Band guitarist

Moby Grape used to play a lot of double bills with the Dead. We’d sit up there in the little upstairs room at the Fillmore with, say, the Dead, Big Brother, Moby Grape, and the Airplane. We’d all sit up there and chew the fat, laugh. They’d rotate—each band got to play twice at most venues. So, whoever played the first also got to play fourth, which was a perfect place to play. The idea of top bill and all that, the only way you could tell probably was to look at a poster, and then they shared that pretty evenly, too. It was pretty cool. There were short breaks between bands; Bill Graham ran the show, so it wasn’t long breaks!

I’ve always said, “If it wasn’t for the Dead …” The Dead was the strongest draw here. They were the epitome, the beginning of the psychedelic scene. They actually got it started; we just winged in with them. The Dead and the Airplane always helped us out, got us into the Fillmore and the Avalon. On weekends, they’d do the Fillmore, and after hours, if they still wanted more action, they’d come over to Sausalito and play on this old ferryboat called “The Ark.” We’d jam until 6 in the morning, Janis Joplin and everybody. We kept going, and then at 6 in the morning, they’d serve eggs and bacon to all the hippies. A Bloody Mary if you wanted it.

That was such extreme fun. We always had the Ark to go to. The Sons of Champlin would come over, and we’d have these big jams. Four in the morning was nothing. Everybody was still having fun, jumping around. The police weren’t extra heavy; once in a while they could be, but overall it was pretty loose. You never had to worry about getting stopped for having a binky (translation: a joint). You never got in much trouble for that. We used that in a song.

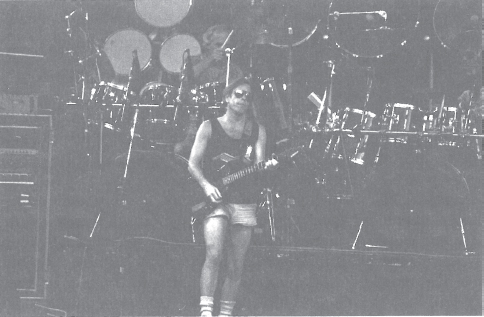

Onstage at Madison Square Garden, 1988. Courtesy of Steve Eichner.

David Gans

Musician, writer, radio producer

In October 1978, Weir got me up onstage to watch at the Winterland one night. Along about 1982, I had fairly regular access to the stage. To me, it was really cool to be able to watch the musicians interact that closely. Being a musician myself and playing in bands, I’m used to the weird perspective of being onstage. Instead of hearing it through the PA the way it’s supposed to sound, you’re hearing it from this incredibly distorted place of being right near one set of speakers. You learn how to hear what’s going on from that perspective. It was a tremendous privilege to be able to watch the musicians from that close-up.

Sometimes it was a weird thing because there are people on that stage who thought I was an intruder and that I’d sort of barged in and pushed my way in there, and they weren’t particularly welcoming. After a while, I figured out that being onstage wasn’t important enough to endure all of that weirdness. I didn’t want to be the bearer of weirdness, and I didn’t want to be the recipient of weirdness. Having had the experience enough times, being up there and seeing it, I was able to just go back out to being among the audience, where I was much more comfortable. I realized that I was happier among my friends in the audience, that it’s okay to be a Deadhead, a spectator, a fan, and go out there and listen to it from the seats where you’re supposed to be to hear the music.

Susana Millman

Long-time Deadhead and GD photographer; aka Mrs. McNally

I met Rock and Nicki Scully after my introduction to the Dead through Dick Latvala, and through them I got my first passes and then maybe even a laminate or two now and then. And then I met Jerry. I was with a couple other people, and they were comfortable with the whole backstage thing, like my friend Sue Hill was a good friend of Donna Jean Godchaux’s. So in the ’70s, I was always with her, and that was perfect for backstage because I was good friends with her.

I was always more comfortable around the Garcia Band and RatDog backstage than I was around the Grateful Dead. One of the funniest backstage stories I remember was somewhere around the late ’70s early ’80s. The Jerry Garcia band was playing at Keystone Berkeley, and Dick Latvala was at the backstage door; he and the security guard had gone to Berkeley High together. Bobby came to the show, and the guy didn’t want to let him in until Dick came out and said, “Oh no, he’s okay. He’s Bob Weir with the Grateful Dead.” That was really pretty funny. Bobby wasn’t bothered by it at all.

Another time, Jerry and I were in a van together in New York, and when we got out of the van, the girlfriend of the photographer I shared a studio with was an ice skater, and she was giving Marushka Nelson ice-skating lessons. I get out of the van with Jerry, and this voice calls out, “Susana!” And Jerry was so relieved that nobody wanted him, you know? It’s kind of like when a dog smells that you’re afraid. They know you’re not acting like your normal self and being more like, “Oh, you were in a van with Jerry Garcia? Oh my god! What’s Jerry like?”—rather than just treating him like this guy who happens to be Jerry Garcia. You just have to be part of the mix. If you’re objectifying them, you’re depriving them of their humanity.

Timothy Leary

Chaos engineer

The first time I ever got onstage with the Dead was the first Human Be-In in Golden Gate Park, January 4, 1967. It’s a powerful memory. It was miraculous. That was the first time there was that kind of show in numbers. There was no advertising, only underground radio and word of mouth—and, wow! They jammed, and suddenly forty or fifty thousand people showed up. It was awesome. It was a small little stage, and with Hell’s Angels around, there wasn’t room for anybody else!

We thought, “Shit! Good Lord! Look at all these people!” We got a sense of the demographic power the music had. Of course, Owsley was there, but the Dead! They were the only band I remember from that day. I went to a lot of their shows in the Panhandle.

Waylon Jennings

Rhythm-and-blues country musician

One time we played somewhere on a one-hundred-and-somethin’ street in New York, with the Dead and the New Riders of the Purple Sage. See, my problem was … I realized, “Hey, this is a no-win situation for me ’cause here I am, I’m a loner, and them little kids had come to see the New Riders and the Grateful Dead. So that was a no-win situation. I got outta there!

Ramblin’ Jack Elliott

Folk musician, Woody Guthrie friend

In 1971 or 1972, I played in New York with the Grateful Dead and the New Riders of the Purple Sage. We were there about a week, playin’ different gigs. The first one was at Madison Square Garden. The second one was somewheres in Long Island, and the third one was in New Jersey. Bobby loaned me a guitar for those gigs. It was the only time I ever actually played with them. I was on first, then the New Riders, and then the Dead. Well. I didn’t like the audience. They just got off the subway, and they were still walking to their seats.

Then there was the time I had a gig to play where I was opening for Jerry at the Santa Cruz Community Center. They had a bad sound system there, and people couldn’t hear me, so they weren’t listening ’cause they couldn’t hear. It was a rainy day. I was very pissed about the crowd reaction. It was bad. I went home and went for a ride on this horse named Brinkham late at night. I got lost up on top of a mountain and couldn’t find a trail to get back home. I figured I was gonna spend the night sittin’ cross-legged underneath my horse’s belly. I was sittin’ under there, hangin’ on to his front legs with my hat on, just touching the bottom of him with his saddle on. I finally did find my way home, but I caught a bad cold.

I had to play another gig the next day opening for Jerry after getting stuck all night in the rain, so I could barely sing. When I got up there, they called the gig because it was outdoors in the mud in the football field at Sonoma State College in Cotati. So they put it off till the following week. They gave us a rain date. I went up to do the rain date, and I was over my cold and I sang okay.

Another time I played my favorite gig in Denver, and there was a Grateful Dead concert the same night. After my show, I went and hung out with the Dead. I remember hanging backstage before the show, and I was amazed that Jerry would be so congenial as to visit with me, right on the stage when the curtain was closed, right before the show. I thought, “You shouldn’t do this to a performer, hang out and talk to ’em like this.” He didn’t mind. He was just happy to talk. But I remember him warning me—he said, “Don’t get in the way of a gorilla. You’ll never be invited back.” That was very good advice, and I’ve never gotten in the way of a gorilla. I’m always very careful about them backstage because if you trip one of those guys when they’re carrying those hundred-pound speakers around …

Ramrod and I are the best of friends, so I’m not too worried about him. He’s always my best friend when I go see a Dead concert. He’s the one who welcomes me in.

Rick Begneaud

Cajun chef for the Dead, artist

One time I got to take my friend Chuck backstage. I said, “Chuck, come with me,” and I took him to go onstage. Rose was the woman at the top of the stairs to the stage. Rose and I had become good friends. But she always had her limits.

I’d be like, “Hey Rose!”

And she’d go, “Hang on. Who got you in?”

And I’d say, “Kid,” or “Bobby,” or whoever.

She wasn’t like, “Oh, come on in!” She knew her work, and she was very careful.

Anyhow—she let us back, and I took Chuck up to the couch onstage, which is next to Phil, right in the wings, looking down the line at the whole band. We’re sitting there, and we’re ha-ha-ha-ha high. Chuck is just blown away. You look out into the audience, and there’s like fifty thousand people. I just thought how wonderful it was to take Chuck to see something like that.

I’ve never let that go: how grateful and lucky and special it was that I was allowed to do that. Not only to be there for myself but to bring my best pal up and sit on the couch and look down the line at this thing, this band, that was so very special to me. That was such a beautiful moment for me.

Another time, my friend Lou Tambakos got me some tickets for the Greek Theater shows in 1981. I brought him a bottle of champagne, hung out. Then I went to the show, and somehow I got put on the guest list. I guess Lou put me on some sort of special list. I went up to will-call and literally skipped back to show my friends Rick Welch and Cliff Broussard these special backstage passes I got. It was incredible because the Greek is so special, and it was my very first backstage show, plus we got to sit in special seating. It’s so easy to see the band from there.

That was the first time I really connected with how this was home turf for the Dead. They were actually home, so there was a different feeling for me at that show. And, we got to go backstage! We didn’t really meet anybody, but we were totally excited. Absolutely.

Later on, Dennis McNally was always accusing me—because I had a backstage pass—of walking people in. And I was like, “Dude, I have never walked anybody in. I have a backstage pass, and I go out and I come in and I never walk people in.” He was always determined to believe that I was walking people in. We’ve become good friends, though. He calls me Banjo.

He finally one day said, “I always figured you had too many friends and that you must be walking people in.”

I said, “I never once, out of all those years having a backstage pass, ever walked anybody in.”

I had an encounter backstage with the roadies at Cal Expo in 1986 or ’87. I went with the only guy I knew in California, my friend Lee, who worked in the garden at the place I rented. Before the show started, we’re hanging out backstage, and Steve Parrish is up on the stairs right on the stage.

He says, “Whadya doin’ back there?”

I said, “Nothin.”

He goes, “Why are you back here?”

And I said, “Weir got me backstage.”

And he says, “Yeah, right. Everybody says that.”

I go, “Well, you should ask him.”

And he goes, “I will ask him!” Just being a—you know how they always are.

I thought I was going to have to drive Weir home that night because he’d asked me before the show. Lee said, “We have to take this E backstage!”

I said, “Dude, I’ve never had it before. I can’t. I’ve got to drive Weir home after the show.”

Lee said, “C’mon!”

So we go backstage, we talk to Weir, and Lee says, “Rick says he has to drive you home after the show. Does he have to drive you home after the show?”

And Weir said, “Whatever, not really.”

So Lee just stuffed some pill in my mouth, and I’m like, “Oh shit.” I didn’t know what to expect. Let’s just say I had a good time. But at the break, I was so high I went to my car and got my camera and came back to the show and started taking photographs. I needed something in my hand, you know? After the show, we go backstage. I’m still pretty buzzed, and my buddy is playing football with Bill Graham and all the guys, and I’m just taking some photographs, hanging out. One of the security guys comes up to me and says, “Hey man, I really hate to do this, but I’ve been asked to walk you out of here.”

I said, “Really?”

He says, “Yeah,”

I go, “That’s cool.”

He says, “I feel so bad. You’re not doing anything.”

I say, “Who asked you to do that?”

He says, “Steve.”

So I’m like, okay. I tell my buddy I have to go, and the security guy was so apologetic; he felt really bad because he didn’t want to do that. So anyway, I walk out, I’m cool with it—we leave.

And I think it was the next weekend, maybe Frost or some close show, when I saw Steve again. He was like, “You know, I just thought you were some joe that slipped in or whatever…. I know. I talked to Bobby—you guys are good friends.”

And I said, “I’m not trying to pull any wool over your eye. And I get it—that’s your job.”

And it is. Anyways—those guys. I love those guys. They’re good pals now. I was telling that story to someone about Parrish, and they said, “Don’t feel bad. Parrish threw Jerry’s brother out before!” So, all right!

Jerry Miller

Moby Grape/Jerry Miller Band guitarist

Backstage, I was usually doing my own thing. Nothing really that crazy, just chatting and hanging out. I smoked many joints with Jerry, but that’s what you did then. All you had to do was breathe up near that dressing room at the Fillmore or the Avalon!

I remember Jerry needed a string one night. His roadie come tearing in there with this stuff for him, and this big old redneck is standing there like he’d never been there before with this crewcut kind of deal, and the roadie stepped on his toe a little bit, and the guy starts chasing him, running past me, runs right up to the dressing room, and the roadie knows this guy is behind him, chasing him, and getting ugly. He gives Jerry his strings, takes off his shirt, and he goes out there, and the guy is still standing there. The roadie has got muscles like Arnold Schwarzenegger, but you couldn’t tell because he had a loose shirt on. So he comes out there and says to the guy, “Did you have something you wanted to say to me?” and the guy was speechless! I didn’t like the guy. He didn’t fit. Besides, if your toe gets stepped on in those situations, that’s just the way it is. Don’t get all rednecked and ugly about it. The roadie was getting strings to Jerry, so that was more important than worrying about this pissed-off guy right then. But after he had free time, he could go back and say, “Okay. What were you saying, asshole?”

John Perry Barlow

Dead lyricist, cyberspace pioneer

I don’t know when this was, maybe 1976, maybe ’77—yeah, coming into ’77. The Dead were playing New Year’s Eve at Winterland, so it must’ve been at least that early. This was the last New Year’s Eve Winterland. I had come out on a whim just at the last possible moment. I’d just gotten together with my wife. Well, we’d been together awhile, but this was still a strange zone to her a little bit.

In any case, we’d been up onstage, and I had taken a powerfully large dose of LSD, and so had she, I think. We were up onstage, and Weir had this girlfriend at the time, Janice, she was just like … mist. She was cute. Cute, but real light. Real diaphanous. She just kind of drifted off at a certain point, and there was this zoo going on backstage that was I think the worst I’ve ever seen it. Maybe it was just because I was really high on acid, but it was like the night circus. It was Fellini on bad acid. It was like the ninth circle of hell. Everybody’s face was melting off, even if you weren’t on acid! Oh, man, twisted, contorted people dressed in all these extravagantly startling bad clothes. Yuk! It was the 1970s. The ’70s was not a pretty decade. It was ugly. And I’d been on the ranch for quite a while at that point, and I wasn’t used to it. I was doing my own things, and I’d pretty well adapted to that other environment.

Anyway … Weir’s girlfriend had taken off, and because it was the last New Year’s at Winterland, [Bill] Graham was truly gonna kick out the jams. I mean, it was gonna be Circus Maximus at midnight, and he was gonna descend from the clouds as Uncle Sam, some sort of psychedelic Uncle Sam. It was really gonna be special. Well, right before midnight, Weir says, “You gotta go find Janice. She’s backstage someplace. I can’t leave her out there for New Year’s. I want her onstage. Can you go get her? I gotta stay here.” So I said, “Alright. I’ll go look.” And I went back into this crawling mass of horror. I looked high and low. I couldn’t find her anywhere. I couldn’t find anybody I’d ever seen before in my life, in fact! There was no solace to be had. So, it’s about five minutes to midnight, and I come back to the stage entrance, and I presented myself to go back onstage, and there was this huge black guy. He was like a linebacker for the Raiders guarding the stage. He said, “You can’t go up there.” I said, “Yeah, I can, I’m John Barlow.” He said, “Nobody can go up there.” I said, “Listen, I wrote the song that they’re playing right now. My wife is onstage.” He said, “I don’t care. If you were President Carter, you couldn’t get on right now.” And I was feeling kind of panicked about this. Right at that moment, a couple of what appeared to me to be obvious groupies flounced on past, and neither one of them was President Carter. I thought, “Well, fuck this! If they can go, I can go! Screw it!” So I went past, and this guy grabbed me and threw me up against the wall, and it just unhinged me, and I had the strength of a thousand men that you’ve got on LSD sometimes, and I came back at him and hit him so hard that I dislocated his jaw. Which I didn’t know at the time, but I knocked him down sideways. Hit him really hard, but I bounced away from that shot, the wrong direction—not towards the stage, but away. Back to the hellhole!

Billy, Bobby, and Mickey playin’ Shoreline, California, 1988. Courtesy of Rick Begneaud.

So then I just sort of faded back. I thought, “I’m gonna let this ride for a little bit. I’m just gonna bide my time.” So I went backstage, and I suffered through the turning of the New Year and whatever explosive activity was taking place out on the other side. And I was in hell! So after about twenty minutes of people hugging and grimacing and kissing, it’s finally time for me to re-present myself … I think it will have blown over by then. Besides, in my view, much time has passed! We’re not even in the same geological period anymore. This is not the view of the guard for whom this whole incident is still fresh as the moment it happened! The paramedics have come, the cops have come, I come back, and the next thing I know, whang! I’m in handcuffs and charged with assault! I’m being led out onto the street and I’m thinking, “Uh-oh!” This is serious! Here I am without any ID whatsoever, high on LSD, charged with assault, holding drugs, and there’s no good end to this. They’re just gonna take me away, and Lord knows if anybody will ever see me again.” Truly a paranoid moment.

Turns out, Alan Trist—he ran Ice Nine many years, good friend of mine, originally came onto the scene as a close friend of Robert Hunter’s—way back, before there was a Grateful Dead. He’s English. Lives in Oregon now. He was too fine-tuned a unit to be in that society as long as he was. Anyway … I didn’t know he’d seen me. All I knew was that I was in irons, and that I was being hauled off into the belly of the beast. I’d been an antiwar protester, so I’d been handcuffed before. But this was different. Never for doing something that could conceivably be a crime as far as I was concerned. Then I went into this thing thinking, “Maybe I really hurt this guy,” which I had, actually. But I also … I got outside, and I had this sort of patriotic moment where I thought, “Now wait a second. This is America. This is not Bolivia. What I have to do now is to get really clear and focused and explain to this cop precisely what happened without any bullshit whatsoever. To the best of my ability to even speak!” and I was having some difficulty doing that!

“I just have to make human contact with this guy. He’s my fellow American! He’s not a pig.” Right? So I start in on him, and I’d pretty well gotten this accomplished. In fact, he’s taking off the handcuffs when we are descended upon! Turned out that Alan Trist had seen this go down and had immediately assembled all the troops he could think of, including Hal Kant, our lawyer, who is a true piece of work, John McIntyre, who was then managing the band and can be a truly operatic fussbudget, and Bill Graham, who was still dressed as a psychedelic Uncle Sam with plastic confetti hanging off him! They all jump this cop and demand my immediate release. The cop puts the handcuffs back on, and now it’s like I’m booty! I’m being held hostage because this group of people is putting a lot of pressure on the cop, and not going about it right at all! I’m trying to explain, “No! No. listen, just leave it. I think we got it covered here.” I almost got hauled off after that because these guys were so insistent on having me released. So, I was rescued. Sorta. By Uncle Sam! And that’s the way I entered the New Year …

It turned out that Janice, Weir’s girlfriend, had gone down into the garage underneath Winterland and curled up in the car and gone to sleep, so there would’ve been no way I could find her.

Now that’s problems with security! This guy was too willing to turn himself into a machine. The problem with him was that he had his orders. It turned out that the women that went past were Graham employees. One of them was Bill’s personal secretary, which I didn’t know. So there was good reason why they went by me.

Dennis McNally

Publicist for the Dead thirty-five years, self-proclaimed Deadhead, more than nine hundred shows

The whole backstage scene in general—if you don’t have any friends back there, which at the beginning I didn’t really—why go there? Well, you know, that lust—there was once a young woman out in the audience who saw my laminate, and she just about wet her pants and said, “Oh! You can go backstage! Oh that’s so cool! That’s so cool! That’s so cool!”

And I looked at her and I said, “You know, really, unless you’re invited into a room, a band member’s dressing room, it’s a boring place.”

She said, “Oh no! It’s a wonderful …”

I said, “Come here,” and I walked her through backstage. I said, “You know, there’s nothing going on here. Unless you’re actually invited, there’s just no point.” And I walked her back out and whatever.

Backstage stories, let’s see …

There was a two- to three-year period—1992 to 94—when the Chicago Bulls would win the NBA championship and about ten days later we played Soldier Field, and Phil Jackson was a Deadhead, so he would come. Ramrod was always a particular basketball fan, so Ramrod would sort of shepherd him around backstage. Weir’s a basketball fan, Mickey’s a basketball fan … because of Walton, they started paying attention to it. And I’m sure he would schmooze with Jerry—he’d be interested in doing that.

Tony Bennett’s son, I think, was a Deadhead, and Jerry always schmoozed with Tony Bennett!

Barlow was somehow connected with George Plimpton, and they together brought Paul Newman to a show. I remember seeing them backstage; I was busy, and I didn’t pay much attention. But I remember seeing Paul Newman at a bit of a distance, thirty or forty feet, and thinking, “My god, he really does have the bluest eyes I’ve ever seen.” Just extraordinary.

Jane Fonda kissed me once! That was a great moment. Quite politely, we’re not talking about a tongue and yet—man! My toes were curling. It was just a polite, proper, married-lady kiss, except, because it was Jane Fonda, there was a little more to it—it was Jane Fonda! It was a great kiss. I had done something that even she couldn’t do for herself: I made her look good to her eighteen-year-old child. The eighteen-year-old did not give a rat’s ass that his mother is Jane fucking Fonda, but he was a Deadhead, so I put him in the pit, which is an intense experience that most people don’t get. And so I made Jane look good. I put the both of them in the pit, and the kid was just wetting his mouth—not even as a joke.

Carly Simon came to a show, and she was extremely sweet. I escorted her. For whatever reason, the stage was insane that night. She had seats, and she said, “I’d really rather watch the show out there.”

I said, “Well, let me walk you out to your seats.” Then, at the end of the set, I walked her backstage. She was very touched by that and sent me flowers the next day. It’s the only time I got a major thanks!

Kiri Te Kanawa, a very famous opera singer, came to a show. There was a buddy of Weir’s who’s an opera singer, and he connected us with a bunch of opera people. One time there was a recital at a home on Riverside Drive in New York overlooking the Hudson River, just an amazing house. A number of us went, including Jerry, and then everybody there was invited to come to the Dead show the next night at the Garden. Kiri was curious, and she came and had a great time.

Whoopi Goldberg. She bought her own tickets; she was sitting alone with her bodyguard, no entourage, and somehow we found out—I don’t know if somebody saw her or what, but somehow we heard. So I went out and got her and said, “Whoopi, you’re obviously welcome to stay here, but if you’d like, you can come up onstage and see it from that angle, which is different.” And she went, “Oh, hell, yeah.” And so she did.

I had it the best of both ways because I was in the pit and that was my world because of the photographers. I mean, I ran the pit, and, as a result, I’m between the stage, and the audience—especially in stadium shows where you’ve got this deck, so you’re above the audience but still below the stage. Being in the middle of those energies is incredible.

I spent a fair amount of time onstage. I had been the biographer for a couple of years before I even got a laminate. Eventually laminates—they gave out like five hundred laminates—but when I started, it was like blood family, maybe a couple of friends, but otherwise it was for real if you got a laminate. So one day in 1983—I’d been at it now two-and-a-half years—Parrish starts yelling at me, and I kind of looked at him and I said, “Steve, you know, I can’t even tell whether you’re just goofing on me or mean it. So talk straight—tell me what you want.” He was annoyed because they hated having people watch them work. It was annoying to them. But he finally decided that I was okay and that he was going to let me hang around, and he invited me to be on the stage. And that’s when I started going on the stage—only after I got a formal invitation from Steve.

There was a show at Madison Square Garden, one of my first shows backstage, and Parrish was expecting me. As you would well expect, if you’re invited to be on the stage, you’re going to go on the stage. I was slightly nervous and being very careful back there because somebody once did really destroy the lighting for one side of the stage because they accidentally kicked a plug out.

So I spent the first set up onstage, but at intermission I looked at Parrish and said, “I got to see ‘St. Stephen’ from out in front.”

He looked at me and said, “Oh, you are a Deadhead.”

I said, “Yep.”

And I went out to the front of the stage when they were going to play “St. Stephen.” It was one of the more magical moments of the Dead’s whole career, that song. They played it three times on that particular tour: they played it once at the Garden brilliantly, just fabulous. They played it a second time four or five days later in Hartford, and it was, eh, not great. And then the next shows were at home. We did our own shows at the Marin Vets Auditorium. It’s only two thousand or three thousand seats. We were sticking a thumb in Bill Graham’s eye—that’s what it boiled down to—and saying, “Fuck you,” and making him nervous by doing our own shows, proving to him that we could. Because it was a home show, everybody was grabbing band members and saying, “You guys save all the good stuff for the East Coast. You treat us home folks like shit.” Which, there was a greater truth to that. There was more energy on the East Coast. They tended to play at home without much rehearsal. And before a tour, you know, they’d do a home show and then they’d go on tour. Well, by the time they got to the East Coast, they’d be properly warmed up.

Anyway, they were just hounded to play “St. Stephen” for the home folks, and the band finally gave in and … it sucked! It was a terrible rendition. That was the last time I ever requested a song from them!

Herbie Greene

Rock-and-roll photographer

Backstage became more of a family thing. There were always kids there. My oldest daughter grew up backstage. All the little girls loved Bobby, chased him around.

Chuck Staley

Restaurant owner, Roswell, Georgia

This wasn’t backstage exactly, but a lot of venues would block off the back of the stage. At Oakland Coliseum, they didn’t block it off—and they put speakers back there, and you could see right on to the stage. So if we could, we sat in the back of the stage, and we loved it. It was so different from back there because you could see stagehands working. We’d always laugh because Mickey would lose his shit back on stage, screaming at the guys because his stuff wasn’t sounding just right. I remember one year he literally picked up one of his things from the beast and literally threw it, and the guys came running out—and you could hear them. You could see Mickey yelling, “What the fuck are you doing? It’s not working!” My friends and I were just like, “What the heck?”

There was never anyone back there, and no one ever bothered you. People always want to get up close. I know what everybody looks like. I don’t need to kill myself to get all the way up front just to get bombarded. We wanted to be where we had room to dance. It was head down, eyes closed.

Bill Graham wheelin’ it at Cal Expo, 1989. Courtesy of Steve Eichner.

Billy Cohen

Student of Bill Graham, soldier in the music biz, poet, dreamer

In 1990, Bill Graham told his son—my Columbia buddy David—“Have Billy call me up. I want to talk to him.” I used to be able to call Bill Graham up—“Hey I want to talk to you about something”—and he would get on the phone and talk with this crazy kid—me—about shit. I never really could appreciate how outrageous it was that I should expect that I could call Bill Graham up and he would take my call. He said, “Listen, you’re gonna come out here to San Francisco and work for me. I’m going to show you how it’s done.” So I came out to San Francisco in the spring of 1990, and Bill put me under the tutelage of Peter Barsotti.

My first gig for Bill Graham Presents was Dominguez Hills, Los Angeles. I was working with Peter’s son, Dharma Barsotti. He basically grew up at Winterland. He’s an incredible show guy. We were part of the Bill Graham ambience crew, which meant all the backstage production, all the dressing room stuff. The coolest thing was we used to run the drink room backstage.

That show, we played football against Bobby Weir and his guys, who just love him. It was one of those things where we were playing aggressively, but you couldn’t fucking hurt Bobby! But we were playing pretty hard. I can’t remember if we won or lost. He was playing with gloves. It was before the shows. It was funny. It was Peter Barsotti and Dharma and me and some other guys from the crew, and then Bobby and his guys who play flag football in Marin—Tamalpais Chiefs. It was totally far out.