14

GETTING CLOSE

____________

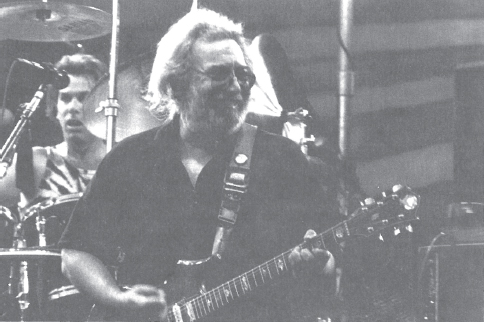

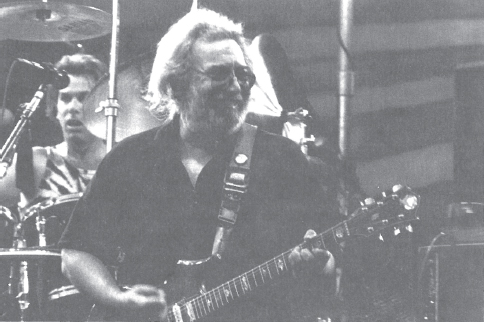

Jerry and Mickey—fun times at Cal Expo, 1989. Courtesy of Steve Eichner.

Linda Kelly

Writer

I remember the expression on his face, his gray beard and hair framing his beaming eyes peering over wire-frame glasses, when I entered the hotel bar. It was the Ritz fucking Carlton, New York City, baby, and the Dead had just played a three-and-a-half hour set up at Nassau Stadium—a bazillion Deadheads worshipping electric guitar ramblings.

I’d been dragged to the show by my girlfriend—she knew the band—because she knew I was super blue. My birthday had just passed and Manhattan was still nippy and unforgiving.

So here it was after the show and I was comfortably numb from the drugs and the music, for which I’d never really cared for having grown up in SF and all its hippie hazy whatever. My girlfriend says, “Jerry’s staring over here. Look, he wants you to sit next to him.” Sure enough, Jerry’s sitting there with a huge grin, saving a seat next to him at the bar. I was high enough to believe it was for me. Turned out that it actually was for me.

We laughed—a lot. He was warm and sweet to sit next to and there was a safety to him, a comfort and nurturing with no sexual innuendo or subtext. His energy was light and protective. I remember looking around the dimly lit, schwanky scenario and seeing people trying hard not to stare, trying to figure out who my stupid ass was. I was a nobody in their world, a nobody who barely even cared for the Grateful Dead. But apparently I offered Jerry some sort of unspoken space, some sort of sanctuary away from being a rock star or deity. He was just a regular guy to me; no pedestal or pretense.

We had an unexplained immediate connection and understanding in simply being together. We were treating each other upon that first meeting the way kids in first grade might—genuinely happy and curious to be around each others’ energy, laughing a bunch and exploring that beautiful place of not knowing someone yet somehow sensing you’re going to know each other for a while—definitely longer than a hot, sweaty hippie minute.

The next day, Jerry’s on my answering machine telling me in that super nasally voice of his that he and Phil will be at my house in fifteen minutes to go to the scuba-diving store uptown like we’d all planned the night before. Note to self: don’t make next-day plans at 4 a.m. after a Dead show.

New York City, 1993. It’s noon-ish, and I’m lying there in bed, happily hungover in my scraggly SoHo apartment, which is wickedly empty thanks to my rock star ex-fiancé’s fit of rage and separation. I mean, he took everything. The only things he left were the bed, the cat, and me—and the answering machine, upon which, as I mentioned, Jerry’s voice is winding its way around the teeny little microcassette tape because these were the days of analog, when phones were still attached to the wall.

So I gather my molecules, slip out of bed, throw on my usual cords and t-shirt, grab who knows what, give a kiss to Slacks (my gray-and-white kitty who the ex so kindly left behind), and haul my ass down the three flights of worn-out marble stairs. Sure enough, right there outside my building, is a black towncar. The backseat window rolls down, and Jerry pokes his head out. “Hey, Linda! Get in!”

So I do. And there we are—me, Jerry, and Phil sitting in the backseat as the driver wheels us uptown. I lean over Jerry and his rolly-polly jolly physicality to say hi to Phil. And Phil’s over there, skinny as the scarecrow, lighting up a big fat doobie, the kind Bob Marley would dig … and Phil takes a big long drag, peers over his glasses, leans forward, and passes me the Chernobyl-sized spliff.

I say hi to Phil, grab the joint, take a puff, and hand it to Jerry as the towncar makes its way uptown. After about twenty minutes, lots of smoke, and a fair dose of shit-eating grinned silence, the car stops in front of a scuba-diving store.

Much to my stoney surprise, we somehow make it across the sidewalk and into the shop. Jerry’s a kid in a candy shop, avid diver that he was becoming. Me, on the other hand, there I am trying to act normal and casual and not high, looking absolutely stoned as I poke through racks of wetsuits and diving gear. I’m trying so hard to do it with purpose, with intention, pretending like I know what I’m looking for … and I look up, and there are Jerry and Phil talking shop, beaming, excited and stoned and happy, and I thought to myself, “Man, this is weird—and that’s okay. I’m with them.”

So after what seemed like four hours, we leave the scuba store to go to the Metropolitan Opera House for afternoon rehearsals of Figaro, and Jerry proceeds to fall asleep on my shoulder, snoring so loudly in the empty hall that the stage crew can’t help but look and laugh.

Another three nights ensue of Grateful Dead music and magic. Riding the spaceship, being onstage, after-parties every night, lunch with Jerry the very last day, and his telling me, “It’s time to come home, girl.” After seven wild years in Manhattan, I moved back home to my native San Francisco within three months.

Dennis McNally

Publicist for the Dead thirty-five years, self-proclaimed Deadhead, more than nine hundred shows

I met Jerry through a man named Al Aronowitz—a New York Post reporter covering rock and roll who was a good friend of Jerry’s. I got to Al because, in 1959, he had done a long series of articles. In those days, the NY Post would run five-, ten-, twenty-part series. In this case, it was on the Beat Generation. It was supposed to be a hatchet job, but he got interested and did things like interview Neal Cassady at San Quentin—got completely obsessed, which was Al’s style. I heard there was this guy with all this unpublished stuff. He was a guy with lots of information on the Beat Generation. He tried to turn it into a book, but he got a little crazy behind that; deadlines were a problem for him.

It’s 1973, I’m twenty-three years old and a reasonably smart graduate student. I went to University of Massachusetts Amherst. It was one of Al’s sort of fantasies that having this young academician around would somehow help him get a book contract for his Beat Generation book, which he did have in 1959. But now, fourteen years later, he somehow thought it would be a more viable project. We worked together on it for nearly two years. In the end, he owed me money, but I didn’t mind because he taught me a lot about writing. And—among other things—he introduced me to Jerry Garcia, which is another thing I would greatly cherish.

One day Al calls me up at Amherst and says, “Get down here.”

And I said, “Okay.”

And he said, “As part of this, we’re gonna do an interview with Jerry Garcia about Neal Cassady.”

And I went, “That’s cool.” So I hopped on the old bus, Peter Pan Bus Co., and got down to his place.

We went to see a bluegrass band, Old and in the Way, at the Capital Theater in Passaic, New Jersey. It was the first time I was ever backstage. I was very shy and nervous, and Al disappeared into the dressing room, where I was not going to follow. I did eventually get to sit in the balcony and see the show. After the show, we go to meet with Jerry at the Gramercy Park Hotel. We beat them back to the hotel, so we’re waiting in the lobby. Jerry and Richard Loren—the de facto manager/road manager/you-name-it of Old and in the Way—come in. And Jerry—well, you know, my memory of this is now so colored from knowing him for thirty years, but I remember, I mean, this is the Jerry of 1969, which is to say black hair … you know, he was beautiful. I mean, there was a period in his life in which he was electric and fun, yet he wasn’t necessarily a handsome guy. But with his beard, there was a certain symmetry and attractiveness. We went up to his room and—I don’t think this is going to shock Mountain Girl—he was with a really beautiful girl. She was new to him. I had brought a copy of Charles Reich’s book, and they were looking at pictures; she was asking questions. She didn’t know anything about the Dead scene. And then we did this interview.

What we wanted was for Jerry to describe what Neal Cassady was like. To understand Neal Cassady, you had to understand nonlinear thinking and, as a graduate student in the academic world, I was linear. I’d had a couple of hits of acid, but I still was pretty lost in the linear thinking. It wasn’t the most successful interview of all time because I kept asking him to explain the inexplicable, and he worked at it. Neal was very important to him, so he made a considerable effort. Actually, it was a good interview—Jerry couldn’t do a bad interview if he tried. I just don’t think much of my performance. I will add two other side comments, which is that Jerry offered me some blow just before we sat down, and I was so focused on the work that I said no thank you, which was, I don’t know, smart or dumb. As we were finishing the interview, he fired up a doobie, and by then I was relaxing and I was more than happy to jump on that.

On the way home, I remember sitting shotgun with Al driving us back to his house in New Jersey, ripped to the eyeballs, reflecting on how good the pot was. I thought to myself, “If anybody on the planet has really good pot, it really oughta be Jerry Garcia.” And that was my first night with Jerry.

After this, I got well into the Kerouac book—Desolate Angel: The Beat Generation, And America. I suddenly started realizing there were all these connections—not least to Neal, as the obvious linchpin—between Kerouac and the Grateful Dead. I said what I really want to do is to write a two-volume history of bohemia or freakdom or whatever you want to call it—since WWII and Volume 1 is Kerouac, and that’s the 1940s, and ’50s, and Volume II is the Grateful Dead, and that’s the ’60s and ’70s. And because I’m terribly slow, you got the ’80s and ’90s thrown in for free.

I decided I wanted to do a Grateful Dead book in 1979. I’d published the Kerouac book and sent a copy to Jerry and a copy to Hunter, Post Office Box 1073, Deadheads mailing address. I didn’t have a clue how else to proceed except that I then decided to write an article about the New Year’s ritual for the San Francisco Chronicle for their Sunday magazine, California Living. It was a long article, and the editor said, “Look, I want to run this article, but I don’t want to cut it, so we have to wait until we have enough ad space to justify this.” So in the interval, in researching that article, I interviewed Bill Graham. He was easy to get to. He’s in the phonebook, and he was more than happy to talk about the Grateful Dead—more than happy.

As I was leaving the interview, his secretary, Jan Simmons (who later was the assistant road manager of the Grateful Dead) said, “Well, if you’re going to do an article about the Grateful Dead, you should talk to Eileen Law at the Dead office.” And she hands me her phone number. Eventually I spoke with Eileen and a lot of other people, and I wrote the article.

In August, Bill Graham runs an ad in the Pink Section of the SF Chronicle of two skeletons, a male and female, leaning up against the façade of the Warfield Theater, and the caption is: “They’re not the best at what they do, they’re the only ones who do what they do.” The words Grateful Dead are not in the ad. It lists thirteen shows—later expanded to fifteen. I pick up the phone, call the woman at the California Living magazine, and say, “Uh, the Dead are about to do this big thirteen-night run at the Warfield, I think it’s time to run my article.” And she does. This series of shows started on a Friday night, and my article was published on Sunday morning. By Monday, Jan had it framed, and it was on the wall of the Warfield Theater. I walk in to the show, and the article is on the wall. People are standing there reading it. How often does a writer get to see people actually read what he or she just wrote?

That same year, the Dead were doing Halloween at Radio City Music Hall, and it was going to be broadcast; they had a series of skits written by Franken & Davis to fill in the gaps because it was a three-set show: one acoustic and then two electric. They were going to do a riff on “Jerry’s Kids” and Jerry Lewis’s telethon. In this telethon, you would be donating money to buy this Jerry Kid a hit of acid and a bus ticket to the next gig! They were going to have a person who was going be Jerry’s Kid.

They had Eileen—being the mother superior of all Deadheads—call eight or ten people to come, and your job being a Jerry’s Kid was to hang out with Jerry for half an hour and tell road stories. This is how I met Jerry Garcia for the second time. I get in the room with him, and there’s Franken & Davis, and six or eight other people.

Fairly diplomatically and ingeniously, if I say so myself, about a minute into the conversation, I managed to insert the words: “By the way, Jerry, I wrote this book about Jack Kerouac, and I sent it to you. Did you ever get it?”

And he said, “You wrote that book about Kerouac?” He hops up, crosses the room, shakes my hand, and tells me it’s the best biography he’s ever read.

During Bob Dylan’s second run at the Warfield Theater, Alan Triste, who was part of the Dead’s business staff, called me up and said, “We’d like to meet with you. Why don’t you meet us at the Warfield?” I said, “Okay, fine.”

I meet them at the Warfield, and standing at the upstairs bar at the Warfield, Jerry says, “Why don’t you do us?” by which he meant, “Why don’t you write a biography of the Grateful Dead?”

I said, “Yeah, I think I could find the time.” Of course, inside I was having multiple orgasms. I went home, got pretty high, and sat at the typewriter saying, “Jerry likes my book and wants me to do a book on the Grateful Dead,” over and over again for about twenty minutes. It was among the happier moments of my life.

One time we were on tour in Washington DC, and I asked Jerry, “You want to meet Lucien Carr?” and he said, “Oh my god, yes!” Lucien Carr was a very close friend of Jack Kerouac’s in Kerouac’s original circle, which included Lucien, Lucien’s friend William Burroughs, Lucien’s friend Allen Ginsberg, and Jack—the four of them.

It was the only time in fifteen years on the road with Jerry when I saw him nervous. No, I take that back. He was nervous before his wedding, and he was nervous before my wedding. He walked my wife, Susana, down the aisle, and he was very nervous about that. It was mostly Deadheads there—friendly, older people Jerry had seen around for years. One of the bridesmaids looked at him and said, “Jerry, you stand in front of fifty thousand people playing guitar, but you appear to be rather nervous right here.”

He said, “Oh, hell yes I’m nervous! I don’t have my magic shield, my guitar.”

At any rate, I took Lucien to Jerry’s dressing room, and Jerry was actually a little nervous about meeting this hero of his. He said, “At last, I meet the real Roland Major,” which is a pseudonym that Kerouac had given him in some book—I forget which. Lucien was floored by that, that Jerry knew his shit. They had a very brief but very interesting conversation. They were intrigued with each other, their two worlds merging. They both enjoyed the encounter. Then it was time for Jerry to go back onstage.

Will Sims

Waverly, Alabama

I know Jerry was probably an extremely sharp and intelligent guy, but he seems like he’d be a funny, happy-go-lucky guy, too. I don’t even know how to put it into words. I just feel like he’s somebody who is just always kind of there. I’m not a religious guy, but I almost feel like I’m talking to him. I don’t want to put him up like god, but at the same time, I talk to my deceased grandmother, like, “You guys are out there—I need you pulling for me.” And Jerry’s definitely one of those people who I feel like … they’re on my team, which may not even make sense to anybody but me. It’s a special thing.

When things are down, I’m thinking, “Who all’s pulling for me and putting that energy out there?” I’ve seen him in the trees, man. I mean, he’s up there, and I feel like I pull him in every now and then.

Steve Brown

Filmmaker, Grateful Dead Records production coordinator (1972–1978)

I was lucky. I was there during a sweet spot with the Grateful Dead. And as much as there were drugs going on all around, everybody was maintaining enough that we could go out and play to sixty thousand people. I’m walking in with the band and hanging out backstage in a trailer while they jammed with each other. If I’d been a fly on the wall with a recorder in my brain, I would’ve had some amazing stuff. But those kind of moments are only in my brain. Magic moments. You remember those times. And hell, if you’re going to live a life and you don’t have some of those moments in it, I feel sorry for you because that’s really what the blessing of life is. And the Grateful Dead offered that to a lot of people.

The Dead were normal kind of folks—kind of a California thing. If you grew up in the Bay Area, you know there are these kind of people. They have a comfortable feeling and consciousness about them that you could relate to as just regular friends. And the fact that the Dead could make this great music and get up onstage and entertain all the rest of their friends made it seem pretty natural and easy to accept.

You’ve got that huge California horizon right off the coast—everything’s possible! And when you’re living where everything’s possible, people want to be cowboys and play rock and roll. “Hey, this seems right!” There was a whole surfing culture out here. I remember reading all my early subscriptions to Surfer Magazine and seeing Rick Griffin’s artwork in there—wow, this guy surfs and he’s an artist. He became one of my cowboy heroes of the West Coast. And then there’s Ramblin’ Jack—he ‘s a real cowboy from the East. He only added to the plot!

I remember at the Fillmore once, I had gotten this ID Magazine, which featured all the bands in San Francisco in 1966. My band was in there—The Friendly Stranger—and the Grateful Dead were in there, too. I’d just gotten it fresh off the press and, at the Fillmore that night, the Dead were playing. They were setting up onstage, and I just walked up and laid the magazine down on Pigpen’s Vox organ and said, “Could you sign this?” I had a Sharpie in my pocket, and Pigpen signed it. I was twenty-two. They knew me from seeing me around shows. Then I went over to Jerry and had him sign it. I walked offstage, and these were the days when they still had rows of chairs up front. I went and sat in a chair next to my friend, showed him the autographs, and said, “Look!”

Hanging around music started early for me. I would listen to the radio in the morning with my parents before going to school, junior high school and high school; we’d listen to Don Sherwood on KSFO, and he would always blow my mind. And then down in my room, I’d listen to KOBY, the rock-and-roll station. This is around 1955, when they were just starting to play rock-and-roll records on the radio. My friends and I went down to the KOBY and watched the disc jockey playing rock-and-roll records. That was like, “Wow!” Watching a guy play on the radio—this is really cool!”

This connects with a lot of other things in my future where this kind of path leads you. The people at the station saw how I’d gotten involved with handling things like coffee, phones, errands for Don Sherwood, and they eventually hired me. I worked for KSFO for five years. It was great. I could go into the record library and find the cool stuff that I knew his program liked to have. KSFO was the biggest station in the Bay Area at the time because it had not only Sherwood and Jim Lang as disc jockeys, it had the Giants, it had the 49ers. It was the sound of the city. It was the big station.

It’s this path you get on; you get in that certain vortex that happens to you, and you wind up—it exponentially seems to get bigger and bigger. I got open to all possibilities early on, and then when drugs came along, it just opened the door a little further. Those kinds of weirdnesses, different kinds of people, interesting people like that, I was exposed to early. I somehow magically, almost blindly, stepped into the dark and would wind up hitting these paths that kept me going that continue to blow my mind. I really appreciate having a life that’s been so rich with that. Not that it’s made me a better person than any other person—it’s just a more interesting kind of a life, that’s all.

I started working professionally for the Dead in 1972, when Jerry walked out of the conference room and told Rakow, “He’s on!” That’s all it took. Kidding. We had a meeting in the conference room, which was very impressive, and sat at the big table. It’s me, Rakow, and Jerry. Rakow had gone through my résumé and talked to me about some ideas that he had, and we kicked this back and forth, and Jerry threw in some stuff. And then Rakow had to go do something and left me with Jerry.

The record company conversation went out the window, and Jerry and I started talking about growing up in San Francisco. We talked about the city stuff mainly, and a lot about music, my working with Don Sherwood and all the celebrities and stuff. We talked for about another half an hour. Then Jerry walked out of the room, caught up with Rakow, and said, “He’s on!”

I wasn’t really touching the ground when I walked out of the building. It was like, “Yeah, this dream came true, too! Oh my god, am I lucky or what?” I’d been the head buyer at this record company, which was the biggest wholesale distributor, and we had our retail stores, The Record Factory, in the Bay Area. And Jerry and Rakow had seen the success I’d had working in the record business. And so my whole deal was pretty much working as planned when I left there. This was a chance for me to be close to really cool, creative people, helping them get their music out to the public.

We kind of ran in parallel lines of the business. They were producing the music, and I was putting the music out there. I’d been in radio before that and was playing the music. When I recorded the Dead on Haight Street in 1968, I wound up flying back to San Diego and playing it that night at midnight. It was almost like a delayed broadcast. They knew about that, and I gave them a copy of the tape. I also gave them that picture of Jerry on Haight Street I took, which he gave to Mountain Girl. She used to say that was one her favorite pictures of Jerry, which has always been a big honor to me. Also the fact that they did a blow up of it, and it’s in the lobby of the Fillmore Auditorium. It’s way cool any time you get something you created exhibited in the holy temple of rock and roll!

From the get-go, there was always more laughing than there was business. The Dead have managed to survive in an alternative mode all these years. Laughing helped a lot. When I was working with him, Jerry was a very kind person in the way he cared about people and their lives. Once they started working with the band, Jerry treated them as part of the family, a team thing with a sensitivity to it. There was a personal level to everything. Yeah. We laughed—a lot!

One of the most important things I learned working with Jerry is to be honest about what you want, what you will ultimately be satisfied with. The grace of being creative with others gives you something even more than what you singularly brought to it because you conceptualize something that then turns into something finer. The act of creation with a group of people is magic. It’s fucking magic. The chemistry of creativity is a real high.

I want to thank Jerry profusely for allowing me to cop a lot of licks off of his personality and attitudes and ways of being—the gentle, kind person that he was, and the friendly, warm, enthusiastic person for life that he was. I borrowed a lot of those personality traits the best I could. I sure as hell can’t say I lived up to bein’ as good as Jerry Garcia at ’em, but maybe some of ’em!

Jerry was enriched by art, by science, by human nature, by things that he just observed goin’ on around him. The comedy of life was pretty much his palette. He was aware of a lot of stuff all the time. I was always impressed with his knowledge and the opinions he had based on a lot of that knowledge.

Having Jerry as a role model has given me, as a result, a very exciting and joyous life. He was a real kind person, a gentle soul. He would do things that other rock artists would not normally do in the way they handled people. Jerry was very friendly and very real.

Susana Millman

Long-time Deadhead and GD photographer; aka Mrs. McNally

I was very good friends with Nora Sage, who was Jerry’s housekeeper and kind of his administrative assistant at one point in time. They were in West Marin, and she brought Jerry to my house once. I was really nervous. He was totally fun and comfortable until I started showing him pictures of himself. And then he just kind of froze up because he did not like pictures, he did not like photographers. He joked, he teased, he was very gentle about it, but he really didn’t like it. With some degree of seriousness and joking, he called photographers “parasites.” Jerry was just one of the most comfortable people in the world—other than the photo thing.

I asked Jerry to walk me down the aisle because it was his suggestion that got my relationship with Dennis beyond the platonic. Dennis and I were neighbors in the City in late 1984, and at that point he had become the Dead’s publicist. But before our relationship went beyond platonic, I made sure that he put my name on the guestlist! And he did, for the Mardi Gras shows at the Berkeley Community Theater, and that was a really good night for us.

They have these catwalks in the ceiling there, and Dennis came, grabbed me out of my seat, and said, “Come on! We’re going on the catwalk now.” I didn’t take my whole camera bag so I didn’t have a long lens, just had a wide-angle lens. The band photos were of these little tiny guys on the stage. That was the first time that I did a montage involving the Grateful Dead. It wasn’t a digital image at that time—it was much more complicated than that. It took more skill.

When Jerry walked me down the aisle, we asked him why on earth he was nervous when he goes out and plays in front of thousands of people all the time. He said, “Hey man, I’m nervous without my axe.” And the reason he was reluctant about walking me down the aisle was that he said any weddings he participated in never worked out. But ours has!

He was wearing a jacket with a t-shirt under it—but he did wear a jacket! We walked down the aisle to “Attics of My Life”—way faster than the tune because we were both nervous. We each had our own reasons, but we were both nervous. I was very honored that he agreed to do it because he was not going out a great deal in those times. This was the end of September 1985.

At the hotel later, a friend of mine who was not a Deadhead was delivering refreshments and a letter to Jerry for his friends, and he didn’t really care too much who Jerry was. He just found out the room number, knocked on the door, and Jerry answered. He gave him the food and the letter, and that was that.

If the people who all loved Jerry could’ve have gotten it together to love each other a little bit better in the name of all loving him, and if he could’ve been more anonymous, he would have lived longer. It’s very difficult to be over-adulated. That’s just in my humble opinion.

Jerry was always kind of a ringleader of fun. He was always talking about something artful, intelligent in just a great funny way. I just think he was a very, very brilliant and multi-talented man. He was a great joy to be around as a human being. My mother was a buyer in the garment sector, and when she got back from our wedding—she’d have tons of Deadheads in her office, and she talked about, “Well, this musician walked my daughter down the aisle. He was a very nice man; he helped me with my coat, he made bad puns, I loved him.” And then she tells them the name, and these people go, “Oh my god! Jerry Garcia helped you with your coat on? Can I touch your coat?” And then she goes on to say, “And know that there are actually a whole bunch of people that follow the Grateful Dead from town to town when they go on tour, and they’re called Deadheads!” And I said, “Yes, mom, I am one!”

John Popper

Blues Traveler singer, harmonicist

A few years ago, I was at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame when the Dead got inducted, and they asked for me to sit in with them. I met Bobby Weir, and he was really nice. The funnest part of that was introducing Gina (personal assistant) to Bob. She freaked out about that one! Playing with Chuck Berry was also really cool. Afterwards, we went up to their big party and hung out. He looked at me and said, “Are you having fun?” and I said, “Yeah.” And he said, “Well, then you’re doing it right.” Then he went off and fell on the bed with some voluptuous woman. I hung out with Vince Welnick, who was having some sort of laryngitis, trying to get him to make noise with his voice by laughing. It was a fun party.

David Gans

Musician, writer, radio producer

I interviewed Bobby in 1977 for Bam Magazine. I went down to Los Angeles and interviewed him. It was cool. He was working on a solo album, Heaven Help the Fool. Me and the photographer, Ed Perlstein, flew down there and went to his hotel in Beverly Hills. John McIntyre introduced us to Bobby. We did this interview, the highlight of which was that Ed somehow persuaded Bob to open a beer bottle with his teeth. He’d heard that he could do that, and Bob obliged us by doing so. Then we all got together and trooped out to Sound City in Van Nuys to listen to some tracks. Ed took pictures of Weir posing on his black Corvette. That was fun. I also interviewed Keith Olsen, who’d produced Terrapin Station and was producing this solo album with Weir.

I was meeting one of my heroes, and I made friends with Weir through those experiences and hooked up with him at other times. I went down to L.A. again in February of 1978, when he was debuting his band, the Bob Weir Band, who were touring behind Heaven Help the Fool, and that’s where Brent Mydland came into the picture, how he got into the Grateful Dead ultimately. I interviewed Weir again at a club down there. I was serious, I was a musician, I was a journalist, and I wanted to understand what was going on. And I think I made a good impression on all of the musicians I interviewed over the course of those years by knowing what I was talking about.

In 1978, Weir was the guy I knew best, and he took care of me at a show at the HaiLai in Miami. Apparently there was some acid floating around, and Weir had gotten dosed. I didn’t know that at the time, but he took care of me and sort of parked me on the drum riser, and I stood over by the guy mixing the monitors, Brett Cohen. I hung out with him and watched what he did, and I listened to the band.

I was very surprised in 1981 when I was able to get an interview with Phil because he pretty much notoriously didn’t do interviews. But he agreed to do one with me, and we had a really, really great time. I was very ready to deal with him. At one point he sort of stopped himself in the middle of a sentence and said, “Boy, you really have done your homework, haven’t you?” I felt like I connected with him very well, and several months later I finished up the interview with him, in the course of which he was talking about all this classical music stuff that he was into, and he said, “You know, you really ought to look at the conductor’s scores.” And I said, “Hey, man, I’m ready. Show it to me.” So on the 4th of July, 1982, he invited me over to his house, and I spent the day. It was like that thing: it was the hip professor who invites you to his house, you smoke a joint with him, and you talk philosophy. Well, this was going to Professor Lesh’s house, smoking a joint, and listening to Beethoven while he got out the conductor’s scores and showed me all this stuff. He brought out records and conductor’s scores, and he showed me all this stuff about Charles Ives, and he played me “Rites of Spring” by Stravinsky, and some Beethoven stuff. I just drank it all in—it was great! He was sharing his enthusiasm for this stuff, and it was just a fabulously great feeling to be learning from him. I was in way over my head, but boy, I had a great time, and I learned a lot. That became the beginning of a creative relationship that I still have with him.

It was just a fairly straightforward suburban house. I would have expected him to live someplace a lot more magical. At that time, Phil was just starting to go out with the woman who became his wife, and he was a different kind of person in those days. The first couple of years that I knew him, there was a lot of partying, and I don’t think he was a very happy guy then. After he and Jill settled down together and cleaned up their act and decided to start a family, they started remodeling the house. Now it’s a really wonderful, homey house.

We connected on a lot of levels, including sarcasm. He was happy to share his knowledge with somebody who was enthusiastic about it and who very clearly appreciated his work. I think it was one of those things where I didn’t suck up to him about music. I had opinions about the music, and I had an understanding of how Grateful Dead music works that I wanted to improve, and our tastes were similar enough that, generally speaking, if he thought a concert was good, it was one that I understood was good, too. I appreciated his criteria of excellence instead of just being a fan who just loved it all indiscriminately. I don’t think it’s possible to be in a relationship with someone who’s a real hero without having a certain amount of undue respect. There are other people I know whose dealings with famous people are characterized by pretending they don’t take them at all seriously and dissing them repeatedly. I didn’t want to do that. I just wanted to have good, creative, intellectual relationships with people whose work meant a lot to me. And I did that over the years.

John Perry Barlow

Dead lyricist, cyberspace pioneer

Bobby and I were bad boys, and we got sent away to the same special school for bad boys at the same time. It was just a prep school in Colorado Springs, Colorado, but they’d acquired some reputation as being able to deal with the smart and incorrigible, which both of us turned out to be. We were both 14, I was coming out of Wyoming, and he was coming out of the Peninsula, Atherton, where he was raised.

You run across people in your life where the second you see them, you know they’re significant people, and you don’t know why. I can’t say that I knew my life had turned such a complete fork as it did on meeting Weir, but I can remember the first day of this English class we were both in, and hearing a thumping behind me. I couldn’t figure out what it was. It would just go thump, thump, thump, thump, thump. I turned around, and there was this gawky kid who had fairly thick, horn-rimmed glasses on and the most sideways expression I had ever seen. His knee was going up and down at about 120 cycles, and his mouth was kind of hanging open, and he just … he did not look fully illuminated, but there was something about him. I just knew that he and I would have a lot to do with each other.

Bobby and I became pretty much immediately one another’s best friend at Fountain Valley, and we were very tight, though I think we were forced into it to a certain extent by virtue of being the two singularly unpopular kids in that school. It was hard to tell which one of us was lower on the totem pole. Bobby was always playing music. He’d go into the bathroom where there was a large space lined with ceramic tiling, which would give an echo effect, and he’d sing and play his guitar all the time, and I’d go in and hang out with him and sometimes sing along with him. Music was basically something that Bobby was doing and that I was participating in in a minor way, and I guess you could say that’s the way it’s always been. I always did other things.

Anyway … we were tight that year, and at the end of that year, even Fountain Valley decided to give Bobby the boot—for sins that both of us had committed. We hadn’t been caught at anything except together, but for some reason, they took it out on Weir. They didn’t kick me out, and I got indignant at the injustice that was being delivered to him by my not being expelled, so I quit. I was gonna go to California and live with his family and go to this truly wacky and also quite wonderful school that he went to next, which was called Pacific High School. It was ultimately a real seed of the Haight—a lot of the faculty there became fairly major figures in the hippie scene shortly thereafter. It was real training camp for what Bobby became. He came up and worked on my ranch that summer and helped put up hay. The assumption was, during the time he was there on the ranch that we were gonna go to California together at the end of the year. When it finally came down, I decided there was something about going off to California and going to this truly avant-garde kind of place—I just had a funny feeling about my own ability to handle a complete lack of structure. And I also had a funny feeling about quitting Fountain Valley. I decided that I was maybe cutting and running in some sense. So when Bobby had to go back to California at the end of May, I said goodbye, thinking that he and I were going to see each other in about ten days and that we were going to be living in the same room for the next year. But somewhere in that ten days, I changed my mind, and I didn’t see Bobby again for three years.

Finally, the Dead came to New York in 1967, and I saw Bobby again. I went down early to the hotel where they were staying. There was Weir, and he had hair down to the small of his back. If he had a thousand-yard stare when I first met him, he had a thousand-light-year stare at this point. He was real quiet, much more quiet than he had been, and much more quiet than he is today. It was like the inside of his mind was turning so many revs that there was jut nothing moving slow enough to attach on the outside. If it had attached at all, it would’ve been, “Blrrlrrrlll”! That was what I thought. Lord only knows what was really going on in there, but it was a foreign country to me. I mean, this was my old buddy, and it was like finding your old buddy has been reprogramed by Moonies or something … but not bad. He was just real different. It was hard to tell what his reaction was to anything. His reactions were very abstract; he was also macrobiotic, so he was translucently thin and had that generally translucent macrobiotic I’m-starving-to-death look.

We were glad to see each other. On some level, our relationship never had anything to do with seeing things the same way. It was more something deeper that we felt connected to. Bobby and I went back and forth between having nothing in common and having a lot of in common. We’d go into phase shifts on both sides where it would suddenly seem like were practically the same guy, and you wouldn’t be able to tell us apart on the phone. And then other times, the polarizing filter would move into a perpendicular condition, and you couldn’t see shit! I just kind of watched the polarization filters turn around.

Then at about three in the morning, Bobby and I walked back to his hotel, which was on lower Broadway. We went through Washington Square Park. It was really abstract, dreamy, and Weir was in this state. It was like I’d fallen into his mind in some way. There’d always been a really open aperture there, and I had just kind of gotten myself in there. I was in the washing machine of Bobby’s mind, bobbing rapidly in the suds!

It was a real hot, sticky night. Bobby had never see New York before, so in addition to being amazed by the universe, which he so transparently is at all times, he’s also amazed by New York! I am, too, to this day. New York has that thing that attached itself to the mind of a hick kid. My mouth is still small and round, and my eyes are still big and round after all these years. They were definitely so that night. So … Bobby and I sat down underneath the Arch in Washington Square. We’re sitting there, trying to have a conversation. It was like, “Well, then what happened?” For him to say what happened attaches itself to so much other stuff, it’s like a little bit of thread hanging out on the sweater of the universe: you better not pull on it! It’s not entirely working on any linear level, but we’re kind of liking it anyway. Then, things got extremely linear.

A pale green Falcon came around the corner and came bumping up at the end of Fifth Avenue there, and it was like the car in the circus where all the clowns get out. Suddenly, there are about six or seven tough—I would say Irish—kids from Queens, judging by their accents. They’re roaming the Village looking for some action. It goes on to this day, kids from New Jersey or wherever—bridge-and-tunnel people—and they all go in a pack because they’re scared of New York. It was a band of those guys, and they’re always kind of tricky. Weir doesn’t get it at all, and I only mildly get it because, for one thing, I’ve been subdued by the gentle sloshing of Bobby’s mental sphere. They’re surrounding us, it’s a clear attack posing. “Hey, you a boy or a girl?”—that kind of thing. They were mostly taunting Weir, but my hair was long, too. They did the whole routine: “Why ya not in Vietnam? Ya know my brother’s in Vietnam. He’s about your age. Why ya not in Vietnam? You got somethin’ against it? You don’t like the war?”

You have to understand, in the context of that time, people who weren’t alive then have no sense of the ugliness that was loose in American society. I actually at one point got served a skinned-out lamb’s head, lying in a pool of blood, with the eyes still in it, in my own home state. The darkness was on both sides, but it was largely on theirs. They really were in an ugly frame. We weren’t that pretty, but they were fucking ugly! They provided by their very presence an energy that was the strongest argument against testosterone I think I’d ever experienced. By this time, Weir and I had both stood up and were preparing to … I was just analyzing the situation, looking for any options I hadn’t previously considered.

Then Weir, out of the blue, came up with the last one that I would’ve considered. He said, “You know, I sense violence in you guys, and I get that sometimes. You know what I do when I feel that in myself? There’s a song that I sing that helps.” One of these guys yells, “Yeah? Like what song, hippie asshole?” and Bobby says, “Can you sing with me? It goes like this: ‘Ha re ha re, ha re ha re, ha re rama …” he launches into it, and I’m thinking, “Completely from left field. Could work. This might just be the ticket. I’m gonna go along with it.” So I start to sing, and a couple of these guys are thinking, “Wouldn’t it be fuckin’ funny if we sang along with these freaks!” and they start to sing! They did! They were singing for a little bit. I’m thinking, “Amazing! Amazing! This is the last thing I’d have thought would work.”

And just at the moment I thought we had it licked, the alpha male of this little troupe suddenly realized that he’d been gulled. He came back around with that wild fury a guy gets when he sees red. “You guys are fuckin’ with us!” Then they just pounced. They treated us like animals. We were down. We were all beat up and bloody. It was scary. I wasn’t sure if they would kiss us or not. I didn’t know.

We just sort of staggered back to the hotel. It wasn’t bad enough to go to the hospital, but we were both plenty sore the next day.

A while later, I was out in San Francisco, and Bobby was sleeping in the central room at 710 Ashbury Street. Neal Cassady would be in there all night awake, throwing his hammer and doing bebop, and Weir would be on this couch in the center of the room with all of his worldly goods down at the end of the couch, often lying there with that look. It was like he was imagining Cassady, who was going a thousand miles an hour. He’s making Cassady up; he’s the dreamer. It was a wild scene.

I’ve gone on tour with the Dead. I road-managed them on their 15th Anniversary Tour. I’d written a letter before this, sort of Moses come thundering down from the mountain. This was kind of at the height of a heavy drug period in their history. It was not a particularly pleasant phase, and I think if you look across the face of American rock—or entertainment for that matter—1980 was not a particularly attractive year. I was on tour with them at that point. It certainly gave me an opportunity to check my on morality. It was very difficult. It was made all the harder because we had the press on us like a cheap suit. I was dealing with all that press as well. The whole thing. The band was very nice to deal with. They were real pussycats. It was difficult for me because I was trying to stay up and hang out with them and get up early in the morning to start making phone calls.

I remember one time Weir got in an automotive duel with somebody down in Mill Valley. We went back and forth: he cut us off, we cut him off … it was boys. Guys just get into that thing. “Well, you motherfuckers,” so we went back and forth and finally pulled over, and he stops, and we all had to get out and yell at each other. This guy looked at Weir real hard, and he said, “Wait a second. Aren’t you … aren’t you the drummer for the Starship?” It completely took a lot out of the moment! Talk about going meta! It was really hard to keep track of the original dispute at that point.

With Jerry … he and I are in and out of phase. We have times where he’s right there, and it’s really fun. We’re not in phase at the moment. I’ve had lots of experiences with all those guys, and I have independent relationships with each of them.

Weir’s little ranch was quite a place. It was goofy! There was a peacock that would attack you if you came out the door and it thought you hadn’t seen it. It was bad enough that they had to keep a two-by-four by the door! The horses in the field across the road became rabid! It was a totally hippie kind of thing, sleeping-on-a wet-mattress kind of scene. Weir had this Appaloosa hammerhead stud horse that he thought was quite a unit. The whole place was very sweet in its way; it was kind of a hippie rustification program.

Herbie Greene

Rock-and-roll photographer

For the cover of In the Dark, they wanted me to take pictures of their eyes. The whole period was magical in that Garcia almost died, but he didn’t, hanging around Front Street and talking about failing eyesight and dental care because we’re all getting pretty old. It was pretty funny! So I’m working on the portraits at the same time they’re working on the album. I’d been taking photographs of them for years, but I didn’t assume I could do an album cover for them. This was right around Mardi Gras time in 1986 or ’87, and while that was going on, they were also formulating the concert tour with Dylan. Bill Graham called me about doing a special picture for it, and … I got to do that.

Backstage at the Henry J. Kaiser, during and after the shows, we did the pictures of the faces and the eyes, but it didn’t work out at all because they wanted to mask out their eyes and just have their eyes sitting in there. It was horrible looking! The next day I did ghost lighting on it and got them like that. In the meantime, Dylan was supposed to show up for any of the three nights, and, of course, he didn’t show up until the last night, and we did the portraits. He didn’t want to be there. The Dead were jumping up and down, and a crowd of people was standing behind me, yelling and screaming. It was a din! It was horrible! You know, you only have a couple of minutes to do these things, because it’s all they’re gonna sit for. But it all worked out. I did the placement, set up the background, set the chairs out, and shot it.

It was kind of exciting that we did the cover and the Dylan/Dead thing all in the little bit of space. The second night, we were doing more pictures for eyes. Bill Graham was there, and we did his—he’s the other eye in that album cover shot. So while I’m there doing this, Mickey walks up to me and says, “I want you to take a picture of this for me,” and he had this mask on his face that had these collaged eyes. It was done by somebody he knew in some roundabout way who’d never been to a Grateful Dead concert before, and he just kind of wandered in with it. The synchronicity of that was unbelievable because eyes were the theme. It was like this mask was made for it. It was grotesque!

They had recorded the basic tracks at the Marin Civic Center Auditorium … in the dark. So they called the record In the Dark, and the whole thing had a sinister quality to it. I wanted them to call it Out of the Dark. But, at any rate, it turned out that the portraits I’d been working on integrated beautifully into the whole concept because they had the black background, they were backlit, and the record sleeve cover was on a white background. It was really pretty remarkable to me, the way the whole package looked. People either really loved it or hated it, particularly the eye mask. That caused a lot of tension inside the band. Some people really hated it, like the producer. He thought I was trying to pull something over on him, and in reality, I wasn’t. People were misinterpreting communication between me and the record company regarding color corrections …. But anyway, after the whole thing was said and done, it was fantastic.

At the same time this is going on, everybody’s gearing up for the Dylan concert. It was an exciting time. The band, of course, had no idea how successful In the Dark was going to be. The Dylan thing was taking the most interest. Actually, the best time I ever had in my life surrounding the Grateful Dead and being in the somewhat privileged position I enjoy with them was being able to go to all the Dylan/Dead rehearsals at Front Street Recording. That was remarkable. It went on for a couple of days, and it was just plain terrific. I was listening to the rehearsal tapes the other day, and it shows me how good it is because they were playing all that material unrehearsed, and they were playing remarkably well. It was magic because everything worked, click, click, click.

Then, a little bit later, I got to do the Garcia on Broadway stuff for Bill Graham. That was great. My ex-wife worked for Bill Graham in the early days at the Avalon Ballroom, so I knew Bill reasonably well. He had his good points and his bad points, just like everybody else, but his bad was horrible, and his good was fantastic! Anyway, he called one day where I was working and said, “C’mon over. I wanna talk to you about this Garcia show on Broadway.” We talked about some ideas of how to do the shot, but nothing specific. He spent at least an hour with me, which to me was like, “Gee, this guy really is paying attention to detail in a way that nobody else would.” An hour of Bill’s time was worth huge amounts of money, but he spent all this time talking about this Garcia poster in a Vegas sort of way. Then, as I was walking back to work, the magician and the guitar out of the hat dawned on me. And that’s what we ended up doing.

Then, of course, when the Jerry Garcia Band was at the Greek, backstage, we got two minutes to shoot it. I put Jerry in the clown suit, which I always love doing—putting people in clown suits, with the little cape and everything. I think Garcia was just having a very unpleasant time. But that was the thirty-second run. He did his setup, waited around an hour, and then they came in and sat there for the thirty seconds they give you. I’m not exaggerating the amount of time. You get no time.

I try to get along with everybody. I get along with the band members, the office people, and most of the crew all the time. Garcia is real easy to love. He’s not hard. He’s a great guy. I know Jerry pretty well. There’s stuff between us, but we don’t talk on the phone every day. I love talking to Mickey—he’s always fun to talk to. He’s very interesting. He’s a fascinating man. I like Mickey a lot because I know him. He doesn’t intimidate me at all. I’ll say, “I’m listening, Mickey. I’m out there listening. You better not fuck up!” I like Kreutzmann a lot. I like them all a lot. Phil’s sort of remote, which is kind of funny for me because I think we’d get along better than we do. And Bobby … I like talking to Bob. I’m an old-timer. Everybody knows my name. And we do business.

Ramblin’ Jack Elliott

Folk musician, friend of Woody Guthrie

There was a birthday party for Bob Weir. Seems to me that it took place in a church on the road leading up to his house. I noticed a Cadillac there with Wyoming plates. It said, “Wyoming 1111,” and then it had a bumper sticker that said, “East or West, Beef is Best!” and I thought, “I’m gonna like this guy.”

It turned out it was Bob’s old friend John Barlow. So that’s where I first met Barlow. He had the ever-present black silk scarf around his neck. I don’t think he was wearing a cowboy hat, but he had boots. In fact, I’ve never known him to own a pair of shoes. I’ve never seen Barlow in anything but cowboy boots and Levi’s, and some kind of plain, kind of striped cowboy work shirt. He’s a handsome man, a character, with a daring personality. I guess this was around 1971 or ’72.

The first time I remember meeting Bobby was when Pigpen died. Their manager at that time was an Englishman named Sam Cutler, who was kind of a cockney from London. He spoke with a loud, broad, cockney accent. He remembered me from England, and he claimed that I had sung at this birthday party when he was about thirteen years old. I don’t remember meeting him in England or being at his birthday party, but he always announced it, every time he introduce me to people. He’d say, “Jack played at my 13th birthday pawty, my 30th birthday pawty and my 33rd birthday pawty.” He used to think of me as like Gene Autry, who’d come over from the United Stated with a guitar and a cowboy hat when he was a kid. But I don’t remember this at all! He says it all the time, so I guess it’s true. He always acted like I was his hero or something. I had a friendly relationship with all of those people; they treated me like I was one of them. I went to a lot of Dead concerts back in those times, but when I say a lot, it’s not like a Deadhead. When a Deadhead says they’ve been to a lot of Dead concerts, it means that they’ve been to 380 concerts. I’ve been to maybe fifteen or twenty Dead concerts in my whole life.

So there was this birthday party for Sam Cutler. It was his thirtieth birthday, and I’m just meeting Cutler for the first time at this birthday party, which took place at Weir’s house. It was also a wake for Pigpen, who’d just died. But then Bob told me this story. He said, “You know, Jack, we met before that party.” I said, “Really? I don’t know. I don’t recall. When was it?” He said, “Well, I was about seventeen years old, and someone had told me you had some marijuana for sale and you were playing in Berkeley. I went, and it was just after you’d finished playing.” I said, “Oh, you didn’t hear my show?” He said, “No, I didn’t hear your show, but I was mainly interested in getting some pot from you. And you were putting your guitar away in the case, in the dressing room, and I walked in and said, ‘I understand you have some pot for sale?’ And you said you didn’t have any.” Which is very true because I’ve never sold pot in my life. I’ve smoke a lot of it, bought some, never sold it. So I said to Bobby, “Gee, that’s pretty weird for anybody to even say that because I’ve never been known to be a salesman of marijuana. I’m a smoker, but I’m not in the business of selling it.” He said, “Yeah. Well, you told me you didn’t have any, and so I left.” So naturally I wouldn’t remember something like that—I mean, it’s not that great a story, but that is the true fact of how we first met. I don’t remember it, but Bobby remembers meeting me because I was a name performer at that time, and he was just some kid!

I used to stay with Bobby and his wife Franki. Franki had a band of her own. She was tired of living in the shadow of a rock star. She wanted to be a rock star in her own right because she’s a Leo. Leo chicks! She played some gigs with me. I was a headline act because I was a name, and she didn’t have any—she was just startin’ out. She had for her band a couple of Canadian guys called James and the Goodbrothers. So I played a bunch of gigs all that summer with her, and between gigs, I’d stay with her and Bobby.

We were a pretty close-knit family. I remember occasions where Bobby was good in the kitchen, and I always enjoyed whatever food they prepared for a party or whatever. I always wanted Bob to show me how you play an electrical guitar. This is of interest to guitar players, perhaps. But he was never interested in playing his electrical guitar around the house. He preferred to play acoustic and jam with me on his Martin. So we would sit around on the floor and play songs together on Martin guitars. One song we did really well and we were both very fond of ws an old Jelly Roll Morton song.

I’ve got some funny stories about Jerry, too. I’m a big fan of Jerry, but I’ve never been to Jerry’s house, so I can’t claim to be a real friend of his, but I love him. We’re both Leos. We have the same birthday, August 1. I have a great craving and yearning to someday get to hang out with Jerry in a relaxed home situation and maybe play some. I jammed with him on guitar for about an hour once outdoors at a big party when his assistant married an American Indian guy. That was about five years ago [1990].

Stanley Mouse

Poster artist extraordinaire

In 1967, Pigpen and I both had motorcycles. My studio was located in one of the Dead houses on Ashbury Street. He would come by and say, “Let’s go riding.” He had a bigger bike, and I had a Bultaco dirt bike, so I had quite a time keeping up with him. We didn’t talk much, we just rode. I like Pigpen. He gave the band a real gritty sound. Me being from Motown, I liked that.

I haven’t seen Jerry for a long time. I saw Bobby at a party in Mill Valley in 1994. Last year, Phil’s kid went to the same school as my daughters did, and I saw him at one of the gatherings there. He certainly was nice and happy. I’ve talked with Mickey lately, and I’m doing some projects with Bill’s daughter, Stacey. The Grateful Dead, the guys in the band, they’re all great guys. They were instrumental in saving my life. For that, I do greatly respect them, and I think that the Deadheads will inherit the Earth.

Tom Constanten

Pianist for the Dead, composer

On tour one time, way back when, American Airlines lost my suitcase. Bless their hearts, they did find it and delivered it to our hotel, Gramercy Park. However, the night I had to go without my clothes, Bob Weir and I went to the East Village to find clothes. Shopping. It was the hippie-heaven clothing renaissance. I found a lot of things. I still have a shirt from that period. It was a good thing, too, because that night, a blizzard hit!

This was around the time we did the Fillmore East, and I met Janis Joplin. It was amazing. She had this reputation, rather well-deserved, of being “toothy” when she needed to be. Sharp-tongued and explaining what she didn’t like about a certain situation … like when one of her musicians got dosed.

I think Jonathon, our road manager at the time, introduced me to her. She had the most gentle handshake. It was like lace, hanging. She was totally gentle, sweet, and wonderful. Pigpen’s line about Janis was, “I had my chance.” They were kindred spirits in a manner of speaking, though I think they might have been more like brother and sister. Pigpen was wonderful. We were roommates on the road. We lived in a house together in Novato as well. He and I were probably as close as two heterosexual males can be.

I think the first time I met Billy was in 1962 or 1963. There was a party at the Chateaux, 838 Santa Cruz Avenue, in Menlo Park, which might also be when I first met Garcia. I was in the kitchen with Phil, his friend Johnny DeCamp Winter, and Lee Adams, who was the resident African American guru. And this guy, later identified to me as “Bill,” stuck his head in the door and said, “Where’s the head?” And Lee Adams said, “Which one?” because we were all heads! Jerry sort of recovered and said, “Oh, let’s see. There’s an upstairs one and a downstairs one …”

Bill is probably the one member in the band who I had the least amount of overlap with, in terms of connections. Although, what there was of an overlap was fine. I remember him inviting me to his houseboat in Sausalito one time. We listened to Vivaldi and Bach and had a great evening talking about what there was about the music we’d found. What worked, what was attractive … there was another time we were at his place, which was near where I lived with Pigpen on Seventeenth Street in San Francisco. We smoke a little something, which I haven’t seen since then—we put on the radio, and it was John Cage. The music just tore it out of those speakers. Everything else sounded just like a continuation of it. A nice John Cage moment.

One time after we’d just come off from the road, a DJ I knew at KTIM woke me up on the phone with the news that Pigpen had passed on. It was 1973. He was twenty. I was not quite awake yet, and my first thought was—because I’d seen him three days before when I went to visit him in Corte Madera—my first thought was, “Wow! What an experience! I’ll have to call him to ask him what it was like when I see him!” Because that’s the sort of stuff he and I would share.

There were signs he was on his way out, but they’re the kind of signs you probably can’t read until you’re in your forties or fifties because you haven’t seen enough examples of them. He was a fully developed individual. Wonderful man. No one suspected he was going die.

I’ve roomed with Bobby a couple of times, too. He, Pigpen, and I were the three who were not druggies at a certain particular stretch of time. I had my phases! Bobby was very much into macrobiotics. Of course, according to him, beer and popcorn are macrobiotic!

Rick Begneaud

Cajun chef for the Dead, artist

I was living at my uncle’s [Robert Rauschenberg aka “Bob”] house in New York, and the Dead were doing the Madison Square Garden run. They had a night off, so I was having a party for them at my uncle’s house. He’s hardly ever in New York—he’s in there once every other month, but it happened he was in town that day. He’s like, “Well, just serve them popcorn.” And I’m like, “Popcorn? I don’t know about just serving them popcorn. They’re not coming over just to eat popcorn.”

My uncle ended up at some AIDS event that night. Everybody came over. I think the only person who wasn’t there was Kreutzmann maybe. I remember somewhere in the evening I was like, “Oh, Jerry’s not coming tonight.”

A few minutes later, the phone rings; I answer, and it’s Jerry. He goes, “Hey, Rick. Sorry I’m late, man. I’ll be there in a minute.” And we all had just a really great evening.

Later, Bob comes in after this AIDS benefit, and we were all lit—but Bob was really lit! He comes in, and he was kind of like—you know, it wasn’t his party. He said, “Who are all these hippies and people in my house?” He had the tape of John Cage’s four-minutes-thirty-three seconds, and he goes into the kitchen on the third floor to watch it. The third floor is where everybody is partying. He wants to watch this thing, and he put it in the VCR and, of course, everybody else has been drinking and partying all night long, so there’s a few rowdy folks in there, and Bob’s like, “Shut up! Everybody shut up!” Finally, he gets up—I know Phil was standing right behind him—Bob gets up and goes to the kitchen doors, which are never closed to the big part of the flat there, and he says, “Shut the fuck up!” He slams the doors. So whoever was in the kitchen had to see the tape. There wasn’t anybody coming through those doors! Bob sat and wanted to watch the silence where John Cage sits down for four minutes and thirty-three seconds. There’s just a handful of us in there, and it was a little touch-and-go, you know? The party kind of thinned out a bit, and Weir stayed on. He and Bob got to talking, and then it was all over. They really hit it off.

Another time Weir came to my uncle’s place for dinner, and it was Bob, me, Weir, and Darryl, Bobby’s assistant. We’re sitting there, everybody’s having several cocktails, and we’re having this really beautiful conversation. It’s probably like two in the morning, and Weir started telling us about this dream he had about Shiva. I mean, it was like a twenty-minute explanation of this dream where he had died. And Weir’s got tears rolling down his face, and Bob’s listening, he’s got tears rolling down his face, and we’re all engrossed in the his incredible story about the dream. And that was the night that Bob and Weir really connected.

I was living back in California maybe a year or two later, and my uncle calls me and says, “I went to the Grateful Dead show last night.”

I’m like, “What?”

He goes, “Yeah, I flew down for the show.”

I was almost insulted, like, “You didn’t check with me? You went to the show without telling me you were even going to a Grateful Dead show?” Bob was so far removed from what I thought of the Grateful Dead. Bob was into all kinds of other, more esoteric, stuff, but Bobby got to him, so they were hanging out a lot. I’m like, “Wait a minute!” I was really happy, I was thrilled to death, but I was like, “Really? You guys are doing stuff together?”

I took my mom—Bob is her brother—to a show in New Orleans, and Jerry told me, “You know, your uncle’s the greatest drunk. He’s the best drunk ever!” Bob will sway, but he’s clear as a bell, you know, his thinking. So it turns out Jerry, Bobby, and my uncle hung out a few more times without me. Bill Carter tells a story—they were all in New York, and they went to some kind of function together that night. Bill said it was like herding cats. “Shit, those guys were just rolling!” on whatever they were partaking in that night. He was having to try and get everybody home, and everybody was going in different directions.

Fast forward a few years, my mom’s seventieth birthday, my parents’ fiftieth anniversary, and Rauschenberg’s eightieth birthday. They were having a party down in Lafayette. I called Weir and said, “My family’s doing this party. Do you want to come?” He said yeah. So Weir shows up with a guitar. My parents had hired this band, sort of a lounge band. I was bummed because I had friends like Dickie Landry and Jimmy Mac and all these other great musicians in South Louisiana—they could’ve put it together an amazing band with Weir. But my parents hired these other guys.

My mom’s favorite song is “Sugar Magnolia,” so I was hoping Bobby could pull it off with this hired band. I was so nervous all afternoon because I’m like, “Fuck, I’ve never heard this band play.” We go in the place, Weir’s got his guitar, and he stands there for a second and listens to the band rehearsing.

I’m like, “Oh my god, this is so embarrassing.”

Bobby says, “Nah, they can play. They’ll be alright.”

I was so relieved!

I had Michael Doucet and Dickie Landry there, so there were all these great musicians. Later that night, it all worked fine. Everybody got in there and played a little bit. It was cool. That was a big deal in Lafayette because people couldn’t believe that Bob Weir was playing there.

“Yeah, he sat in.”

They were like, “Who? What are you talking about? Bob Weir was here last night?”

I said, “He came in for my Mom’s birthday.”

People in Lafayette couldn’t understand this. There weren’t many people listening to the Grateful Dead that I knew of, but my parents loved Bobby—and vice-versa.

He’s just a regular guy. I remember way back when I first moved to California and met Bobby, I started playing flag football with him, Todd Rundgren, and all these other different people out here. I didn’t know who they were. And I remember during our second game, Weir and I were headed out to the field. It wasn’t really the Tamalpais Chiefs then. It was flag football, but we didn’t have a name yet.

Anyway, I remember Weir looks over at me one day and says, “You need some cleats.”

I said, “Yeah.”

And he said, “Why don’t we stop and get some?” I was dirt poor. He said, “I’ll spring for them.”

So we got a pair of cleats and went out and played football. I would come home from those games, and I was so sore. I’d mountain bike and hike and run, but I was sore as shit after those games. Weir’s almost exactly ten years older than me, and he goes out there, and he’s fine. He doesn’t play anymore. Now he’s on the sidelines goofing around and, like I said, being a regular guy.

Here’s a weird Weir story: I worked at Whole Earth Access in San Rafael for a period of time. This guy calls on the phone, and his wife needs this attachment for some KitchenAid thing that mills flour. I look it all up, call him back, we talk a little bit, and I say it’ll be in in a few days. So he comes in to pick up the part, we introduce ourselves, and we chat it up. He’s just a great guy.

A couple months later, Natasha, Weir’s wife, calls and tells me, “Bobby found his dad!” Weir had been looking for his birth father for years.

I said, “That’s so cool!”

Natasha said, “You can come meet him.”

A few nights later, Weir was playing at the Sweetwater, and my mom happened to be in town at the time, and I said, “Let’s go down and see Bobby.”

By this time, my mom and Bobby were good friends, so she was into it.

We walk in a little bit early, and Natasha says, “Okay, you sit here, and you sit here, but this seat’s for Bobby’s dad.” I’m like, okay cool, this is great.

I go to get a beer; Natasha’s right behind me. This guy walks in, and I go, “Hey, Jack! What’s going on?”

And he said, “Rick! How have you been?”

I say, “How are you?”

I look over, and Natasha’s like, “What?”

I said, “Natasha, do you know Jack? This is my friend I met just a few weeks ago.”

She says, “That’s Bobby’s dad!”

I’m like, “What?!”

It was crazy: I knew Bobby’s dad before Bobby knew Bobby’s dad!

Dennis McNally

Publicist for the Dead thirty-five years, self-proclaimed Deadhead, more than nine hundred shows

My favorite moment with Bobby in some ways … it was heartfelt for me because I was truly inspired to be interviewing him. This is probably in the late 1990s. Bobby has a very eccentric sense of humor and, among other things, he’s dyslexic. Though he reads quite a lot, it’s a slow process for him. People have a tendency to underestimate him, his intelligence. [The under-estimated prophet! Very good Dead joke!] But this is not the case. As far as a historical memory, if you can prompt him with context, he is a very good interview. He gave me a lot of good stories.

We were doing this interview once, and he said, “We gotta wind up for now, but I’ll tell you this one story, you’ll like it, and I’ll resume later.” And he proceeds to tell me the story of his twenty-first birthday. This is the period in which, in theory, kinda-sorta-maybe-depending, he’d been fired. He and Pigpen had both been fired—sort of. The Grateful Dead never made decisions like that very well. But at that moment, Bobby theoretically was not playing with the band. Of course, they weren’t playing that many gigs—this is late 1968.

So it’s Bobby’s birthday, October 15, and Bobby’s been theoretically fired. He’s living in the loft of their studio/rehearsal hall, which was in Novato near Hamilton Air Force Base. As Bobby puts it, he slept there and tried to stay out of the way and worked and practiced a lot on his guitar work. He gets a phone call from Pigpen saying, “Hey, I’ll buy you your first legal drink.” Pigpen still lived in San Francisco; he was the last to move out. So Bobby and his guitar get out on Highway 101 South. He sticks out his thumb and tries to get a ride. He’s walking facing traffic, of course, as you must when you’re hitchhiking. His life is not going so well at that moment, and to top it all off, he’s walking backwards, backing up and sticking his thumb out and doing his hitching, and he falls into a ditch with water in it. Being Bobby, he picks himself up, dusts himself off, continues hitching, finally gets into the City, gets sloshed with Pig, and continues his life.

That is a story I had never heard before and have never heard since. That he trusted me with that story, that he dug it up for me, was one of my favorites moments ever with Bobby.

Rick Begneaud

Cajun chef for the Dead, artist

When John Goddard from Village Music in Mill Valley used to have his parties down at Sweetwater, I would sit in the back, and I’d always save a little spot for Jerry. He’d walk in, and he’d come sit down with me, and we’d just talk about the music. It was never about, “Hey Jerry, tell me about this or that.” I think he was comfortable just hanging out with me. We’d have a glass a wine, or he’d have a White Russian or something like that. He’d be telling me stuff about music, the history of this or that. There was no pretense of turning the camera on him. We were just cutting up and laughing. It was fun. Jerry didn’t like “the interview” sort of thing. He talked about so many things, but he was not comfortable talking about himself. He’d talk about the band, music, art.

Billy Cohen

Student of Bill Graham, soldier in the music biz, poet, dreamer

When Jerry was in a coma, I saw an old friend who was a fanatic Deadhead. I said, “Jerry’s in coma, this is it, this is the end of the Dead. This sucks.”

And my friend was like, “Absolutely not. Jerry will be playing again.”

I said, “Dude, you’re crazy. I bet you a hundred dollars it’s never gonna happen.”

Not only did it happen, but shortly after the coma, I’m at Christmas dinner with Jerry. It was far out. I can’t remember if it was before Christmas or after Christmas, I saw this same old friend of mine at the Dead at Madison Square Garden, and I paid him the hundred bucks. He was surprised that his friend who was a broke Deadhead would have the bread!

Chuck Staley

Restaurant owner, Roswell, Georgia

Seeing Jerry at the Warfield was amazingly good because it was so intimate. You could just walk right up to the front of the stage. I’d take a Jerry show over a Dead show any day. It’s just him, in my opinion, at his purest, playing what he loved to play. And then he brought in Melvin and Gloria and Jackie LeBron, and John Kahn. They played every single Jerry show with him—ever, which to me is just amazing. I didn’t know Jerry, but from reading the books, he said he started the Jerry Garcia Band because he thought, “Wait, I can do this, and you’re gonna pay me at the end of the night, and I don’t have to deal with all the bullshit?” That was his way of expressing the music he loved. Not that he didn’t love the Grateful Dead. But seeing a Jerry show was really special. One Halloween show he walked out, and the house lights weren’t completely down yet, so people were still milling around. Jerry walked out and went right into “How Sweet It Is.” He never said a word to the crowd ever when he was up there, usually. But this night he went up to the mic and said, “How y’all doin?” and that place went nuts.