CHAPTER SEVEN

Confronting our Past

Jesus wasn’t white: He was a brown-skinned, Middle Eastern Jew. Here’s why that matters

Robyn J. Whitaker

Co-ordinator of Studies—New Testament, Pilgrim Theological College, and Senior Lecturer, University of Divinity

I grew up in a Christian home, where a photo of Jesus hung on my bedroom wall. I still have it. It is schmaltzy and rather tacky in that 1970s kind of way, but as a little girl I loved it. In this picture, Jesus looks kind and gentle; he gazes down at me lovingly. He is also light-haired, blue-eyed and very white.

The problem is, Jesus was not white. You’d be forgiven for thinking otherwise if you’ve ever entered a Western church or visited an art gallery. But while there is no physical description of him in the Bible, there is also no doubt that the historical Jesus, the man who was executed by the Roman State in the first century CE, was a brown-skinned, Middle Eastern Jew.

This is not controversial from a scholarly point of view, but somehow it is a forgotten detail for many of the millions of Christians who will gather to celebrate Easter this week.

On Good Friday, Christians attend churches to worship Jesus and, in particular, remember his death on a cross. In most of these churches, Jesus will be depicted as a white man, a guy that looks like Anglo-Australians, a guy easy for other Anglo-Australians to identify with.

Think for a moment of the rather dashing Jim Caviezel, who played Jesus in Mel Gibson’s Passion of the Christ. He is an Irish-American actor. Or call to mind some of the most famous artworks of Jesus’s crucifixion—by Ruben, Grunewald, Giotto—and again we see the European bias in depicting a white-skinned Jesus.

Does any of this matter? Yes, it really does. As a society, we are well aware of the power of representation and the importance of diverse role models.

After winning the 2013 Oscar for Best Supporting Actress for her role in 12 Years a Slave, Kenyan actress Lupita Nyong’o shot to fame. In interviews since then, Nyong’o has repeatedly articulated her feelings of inferiority as a young woman because all the images of beauty she saw around her were of lighter-skinned women. It was only when she saw the fashion world embracing Sudanese model Alek Wek that she realised black could be beautiful too.

If we can recognise the importance of ethnically and physically diverse role models in our media, why can’t we do the same for faith? Why do we continue to allow images of a whitened Jesus to dominate?

Many churches and cultures do depict Jesus as a brown or black man. Orthodox Christians usually have a very different iconography to that of European art—if you enter a church in Africa, you’ll likely see an African Jesus on display.

But these are rarely the images we see in Australian Protestant and Catholic churches, and it is our loss. It allows the mainstream Christian community to separate their devotion to Jesus from compassionate regard for those who look different.

I would even go so far as to say it creates a cognitive disconnect, where one can feel deep affection for Jesus but little empathy for a Middle Eastern person. It likewise has implications for the theological claim that humans are made in God’s image. If God is always imaged as white, then the default human becomes white, and such thinking undergirds racism.

Historically, the whitewashing of Jesus contributed to Christians being some of the worst perpetrators of anti-Semitism. It continues to manifest in the ‘othering’ of non-Anglo-Saxon Australians.

This Easter, I can’t help but wonder, what would our church and society look like if we just remembered that Jesus was brown? If we were confronted with the reality that the body hung on the cross was a brown body: one broken, tortured and publicly executed by an oppressive regime.

How might it change our attitudes if we could see that the unjust imprisonment, abuse and execution of the historical Jesus has more in common with the experience of Indigenous Australians or asylum seekers than it does with those who hold power in the church and usually represent Christ?

Perhaps most radical of all, I can’t help but wonder what might change if we were more mindful that the person Christians celebrate as God in the flesh and saviour of the entire world was not a white man, but a Middle Eastern Jew.

Article first published March 29, 2018.

‘Western civilisation’? History teaching has moved on, and so should those who champion it

Rebecca Cairns

Lecturer in Education, Deakin University

The Australian National University recently decided not to accept money from the Ramsay Centre for Western Civilisation to set up a Western civilisation degree. The university joins the University of Melbourne, Macquarie University and others that have also been approached but not pursued any similar arrangement.

The Ramsay Centre has been criticised for its narrow and outdated agenda, and the views of its board members, including former prime ministers John Howard and Tony Abbott.

The processes of making and evaluating history and history curricula are complex. When it comes to public opinion about which histories should be taught in schools and universities, politicians from across the spectrum tend to over-simplify this.

This cycle of political interference stagnates the discussion. The politics of who is represented in history requires ongoing investigation, but the conversation could be moved in a more educationally constructive direction. We should instead ask how history education can better explore competing narratives and perspectives in history.

A history of political interference

Political interference in history curriculum intensified during the Howard government years. Howard revived Australia’s ‘history wars’ by bringing the concept of the ‘black armband view of history’ to national attention. This refers to overly negative accounts of Australian history, particularly in relation to the treatment of Indigenous Australians.

The left and right accused each other of misusing history. Conservatives regarded the history curriculum as too politically correct, biased and postmodern. In 1999, the Howard government initiated the National Inquiry into School History, based on concerns young Australians lacked knowledge of national history.

This resulted in the creation of the National History Project and the National Centre for History Education. The centre was discontinued in the mid-2000s.

Howard re-engaged with the debate in his 2006 Australia Day speech. He sought to renew the position of Australian history in curriculum and promote the teaching of an uncomplicated and structured narrative of the national story.

The National History Summit was launched later that year. Howard’s handpicked team developed the Guide to the Teaching of Australian History in Years 9 and 10.

The election of the Rudd Labor government in 2007 meant the plan to mandate 150 hours’ teaching of stand-alone Australian history was never implemented. Despite this, Australian history and Western history remain prominent in the current curriculum.

History was one of the four subjects prioritised in the new national curriculum, drafted in 2010 under the Labor government. Labor’s world history framework focused much more on Asia, a stark contrast to the structured national narrative supported by Howard. Some criticised the over-emphasis on Western societies in some units, resulting in alternative topics (ancient India, for example) being added.

A review of the Australian curriculum was called for in early 2014, following the election of the Abbott Coalition government. The then education minister, Christopher Pyne, expressed concerns about the national curriculum not placing enough value on ‘the legacy of Western civilisation’. Kevin Donnelly and Ken Wiltshire—both conservative critics of the Australian curriculum—were selected to lead the review. Commentary was again polarised.

The final report highlighted that some submissions were ‘critical of the Australian Curriculum for failing to properly acknowledge and include reference to Australia’s Judeo-Christian heritage and the debt owed to Western civilisation’. Despite this, it was decided the curriculum adequately covered Western history. Only minor changes were made.

The Victorian Liberal–National Coalition parties expressed similar arguments at the start of 2018. They argued the Victorian curriculum had inadequate coverage of Australian history, religious tolerance and Western Enlightenment principles.

Evidence-based approaches to teaching history

To ensure Australian students have access to a range of quality history curricula at school and university, we need to consider the responses of history experts and teachers, rather than politicians. Current history teaching recognises historical narratives are complicated and shaped by multiple and opposing perspectives. They also offer students the critical thinking tools needed to understand these complexities.

The work of Canadian Professor Peter Seixas has been influential in this area. The historical thinking concepts he helped develop provide a framework for historical inquiry and critical thinking.

This framework is built around the idea students need to do more than just recite what happened in the past. Students need to be able to ask why things are historically significant to certain people at certain times. They need to understand the past from their position in the world, as well as different perspectives in relation to their own cultural identities.

This framework is grounded in international evidence-based research on teaching history. Many countries have adapted it, including Australia in its national curriculum.

Politicians who privilege Western perspectives are doing the opposite of what we’re trying to get students to do in classrooms. To be successful in learning about history, it’s crucial students understand world history, contested and rival narratives, as well as how history is used in different places and times. This enables us to move beyond outdated labels such as ‘Western civilisation’.

Article first published June 6, 2018.

Friday essay: On the trail of the London thylacines

Penny Edmonds

Associate Professor History, University of Tasmania

Hannah Stark

Senior Lecturer in English, University of Tasmania

On a cold, dark night in the winter of June 2017, hundreds of people gathered on the lawns of Hobart’s parliament house to join a procession that carried an effigy of a giant Tasmanian tiger (thylacine) to be ritually burnt at Macquarie Point.

In an act called ‘The Purging’, part of the Dark Mofo festival, participants were asked to write their ‘deepest darkest fears’ on slips of paper and place them inside the soon-to-be-incinerated thylacine’s body. This fiery ritual, a powerful cultural moment, reflects the complex emotions that gather around this extinct creature.

More than a spectacle, the Dark Mofo event can be read as a strange memorialisation of loss and a public act of Vandemonian absolution in response to the state’s deliberate role in the tiger’s extinction. It led us to ask: what remains of the thylacine and what does it mean to come face-to-face with thylacine remains in the age of mass extinction?

Numerous ‘sightings’—and scientific research that seeks to resurrect the thylacine—attest to our longing to bring this species back from the dead. Our research takes a different path. We want to look for the traces of the thylacine in this time of great environmental uncertainty, in which species are becoming extinct at a rate never before experienced by humans. Facing our past losses is an important project in the Anthropocene, the age defined by humanity’s impact on the Earth.

We have hunted for some of the 750 thylacine specimens in museum collections scattered around the world. These are a legacy of the period when Tasmania was a British colony and the network of global trade connected this small island state to the centres of colonial power.

In September 2017 we went in search of some of the creatures that had made the perilous journey to the United Kingdom: the London thylacines.

An archive of bodies

In search of what remains, we visited the Natural History Museum of London, one of the premier repositories of natural science collections in the world. In the storeroom, we were able to look through a cabinet containing trays of thylacine specimens, many with their original 19th-century tags attached.

Among these remains were the preserved skins of Tasmanian tigers as well as skulls, bones and one thylacine pup. Stuffed and sewn, with a blind eye of cotton wool, this baby in its white protective tray was the tiniest of thylacine young.

While our photographs of the visit to the museum show us smiling in the storeroom—as travelling Australians we were pleased to be there after our long journey—we were overwhelmed with cross-currents of emotion. The palpable shock of seeing so many thylacine bodies in trays in this and several other collections was a profound recognition of loss.

Some 167 specimens of Tasmanian tigers reside in museums in the UK alone. As such, this small joey is made more poignant by the scale of what we saw. A museum visitor might see a single thylacine on display, where one body stands in for its entire species.

Yet in the storerooms of the museum we came face-to-face with the sheer volume of animal bodies that were evacuated from Tasmania. In a world where extinction is becoming all too mundane, the individual lives and deaths of these animals were palpable.

From the late 18th century, the new Antipodean colonies in Australia and New Zealand were homes for the strangest of new creatures, at least to European eyes. A furious trade began between the colonies and Europe.

New animals of scientific curiosity were avidly collected and discussed at meetings of the Royal Society of Tasmania, founded in 1843. Animals such as black swans, wombats and thylacines were exhibited, examined and circulated. The society members responded enthusiastically to requests from Europe’s elite scientists to send specimens from the colonies.

In 1847, for instance, the society’s committee minutes show that members attempted to source an ‘impregnated Platypus or Echidna preserved in spirits. Also the brains of the Thylacinus [Tasmanian Tiger] and Dasyurus [Tasmanian Devil]’. These were to be collected for the eminent British comparative anatomist and fossil hunter Professor Richard Owen, one of the forces behind the creation of the Natural History Museum in London.

The bodies of animals shipped from the colonies and held in museums have always been important for scientific research; they constitute vast repositories of natural heritage material of immense value. In the Anthropocene age, the value of these animal archives as arks of genetic material has become more apparent, but they are also repositories of loss.

Moreover, many collecting institutions the world over face financial difficulties and struggle to look after their collections. Some collections are deteriorating due to lack of resources and staff, and this might ultimately lead to the final disappearance of the thylacine.

Dead on arrival

We visited the London Zoo archives to find out more about the thylacines displayed there over the 19th and early 20th centuries. The London Zoo was the place to which the first and last recorded Tasmanian tigers were exported—the former in 1850 and the latter, purchased for the princely sum of 150 pounds, in 1926. The very last thylacine outside Australia died at the London Zoo in 1931.

The long sea journey was harsh and many of the thylacines shipped from Van Diemen’s Land were simply declared ‘dead on arrival’. One animal died just eight days after arriving in 1888.

In the hope of offspring, many thylacines were shipped in breeding pairs. Yet these hopeful reproductive futures were often foreclosed when one of them died in transit, as was the case with the final shipment in 1926.

We were lured to the London Zoo archives by the librarian’s mention of the ‘death books’, a remarkable set of ‘Registers of Death in the Menagerie’. Within these weighty volumes we found page after page of neat, looping cursive script listing the dates, names, ‘originating habitat’, ‘cause of death’ and ‘how disposed of’ for all the animals that died in the zoo, beginning in 1904.

As we turned the pages and moved through the years, we witnessed the deaths of the ‘Tasmanian wolf’ among a veritable menagerie of animals from all over the globe and especially from Britain’s colonies—Egypt, South Africa, India, Ceylon, the west coast of Ireland, and Australia—reflecting the imperial networks of exchange and transportation through which these animals were shipped.

Among two black swans found dead within days of each other, budgerigars found ‘worried to death’ and a ‘black-faced kangaroo’, which died of pneumonia in the cold, wet English weather, was the thylacine that died on January 17, 1906. This was ‘Specimen 91’, a female purchased on March 26 two years before.

Yet while there is little information on the cause of her demise, the death books note she was ‘not examined’ but was ‘disposed of’ to ‘W. Gerrard (of Gerrard and Sons taxidermist)’ and ‘sold for 1 pound, 1 shilling’.

Armed with the 1869 plans of the zoo, we went looking for the thylacines’ cage. From the map we could see that thylacines had been kept in a far corner of the zoo, near the banks of a rivulet. Due to more recent building and development, pinpointing the exact location was a challenge. What we did find was a nondescript, brutalist building and an asphalt service road. Of the thylacine enclosure, nothing remained.

This site resonates with the abandoned Beaumaris Zoo in our home city of Hobart, the location of the ‘final’ thylacine death, which sits on the banks of the River Derwent in Hobart behind locked gates. Both of these spaces are forgotten sites of death. They are where thylacines began and ended their journeys, places that link the colony and London through circuits of scientific trade and esteem, where animal lives and deaths were managed by bureaucratic processes, and where humans and thylacines came face-to-face.

But what remains at these sites? Nothing that would tell the sad story of the thylacine.

Deliberate extinction

The ‘last’ thylacine died of exposure after it was locked out of its sleeping enclosure on September 7, 1936, at Beaumaris Zoological Gardens on the Hobart Domain. This death, now so weighted with significance, went unremarked at the time. There were no news reports to record the animal’s passing. Its remains were thrown away.

The extinction of the thylacine is particularly resonant because it was annihilated through human actions; its death was sanctioned by government policy and deliberately and systematically enacted.

Tasmanian graziers demonised the thylacine as a blood-thirsty carnivore that liked to feed on sheep. While the Van Diemen’s Land Company had placed a bounty on the head of the thylacine in 1830, it was the parliament that signed the species’ death warrant. Between 1888 and 1909 the government paid one pound per adult and ten pence per young. During this time 2,184 bounties were paid.

The public knew what it was doing. In 1884 a group of farmers on Tasmania’s east coast set up the ‘Buckland and Spring Bay Tiger and Eagle Extermination Society’ with the explicit purpose of eradicating the species.

The cultural guilt that attends the thylacine is perhaps why it is such an important international symbol for extinction and why the date of the death of the last thylacine is now National Threatened Species Day.

The thylacine’s legacy

The spectre of the thylacine haunts the public imagination and there is significant scientific focus on the physical remains of this now infamously extinct creature. In 2017 there was a spate of highly publicised ‘sightings’ in Queensland and Tasmania.

In December of the same year, scientists reported that they had sequenced the genome of a one-month-old thylacine pup or joey, a curious and pale creature preserved in alcohol from Museum Victoria.

In February 2018, researchers announced they had for the first time completed full CT scans of rare pouch young. Indeed, they found a mix-up: some specimens were tiny quolls or Tasmanian devils, not thylacine joeys at all. As an article in The Guardian noted, the research ‘all contributes to the ultimate end goal of bringing back a thylacine, a project that is technologically distant but theoretically possible’.

However, for scholars Thom van Dooren and Deborah Bird Rose, de-extinction projects blind us to the finality of extinction. They advocate actively grieving extinction because it does important political work. They write:

The reality is that there is no avoiding the necessity of the difficult cultural work of reflection and mourning. This work is not opposed to practical action, rather it is the foundation of any sustainable and informed response.

Australia has the worst mammal extinction rate in the world. The thylacine is one of 30 mammals that have been lost here since European settlement. Thinking through the meanings and politics of the loss of the thylacine is crucially important in this context.

Rare thylacine remains, housed in museum collections around the world, are precious archives that are part of our global heritage. We must take care of them. Moreover, facing this loss directly in the age of extinction is a political act.

Article first published April 6, 2018.

A brief history of fake doctors and how they get away with it

Philippa Martyr

Lecturer in Pharmacology, University of Western Australia

Melbourne man Raffaele Di Paolo pleaded guilty last week to a number of charges related to practising as a medical specialist when he wasn’t qualified to do so. Di Paolo is in jail awaiting his sentence after being found guilty of fraud, indecent assault and sexual penetration.

This case follows that of another so-called ‘fake doctor’ in New South Wales. Sarang Chitale worked in the state’s public health service as a junior doctor from 2003 until 2014. It was only in 2016, after his last employer—the research firm Novotech—reported him to the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA), that his qualifications were investigated.

‘Dr’ Chitale turned out to be Shyam Acharya, who had stolen the real Dr Chitale’s identity and obtained Australian citizenship and employment at a six-figure salary. Acharya had no medical qualifications at all.

Cases of impersonation, identity theft and fraudulent practice happen across a range of disciplines. There have been fake pilots, veterinarians and priests. It’s especially confronting when it happens in medicine, because of the immense trust we place in those looking after our health.

So what drives people to go to such extremes, and how do they get away with it?

A modern phenomenon

Impersonation of doctors is a modern phenomenon. It grew out of Western medicine’s drive towards professionalism in the 19th century, which ran alongside the explosion of scientific medical research.

Before this, doctors would be trained by an apprentice-type system and there was little recourse for damages. A person hired a doctor if they could afford it and, if the treatment was poor or killed the patient, it was a case of caveat emptor—buyer beware.

But as science made medicine more reliable, the title of ‘doctor’ really began to mean something—especially as the fees began to rise. By the end of the 19th century in the British Empire, becoming a doctor was a complex process. It required long university training, an independent income and the right social connections. Legislation backed this up, with medical registration acts controlling who could and couldn’t use medical titles.

Given the present social status and salaries of medical professionals, it’s easy to see why people would aspire to be doctors. And when the road ahead looks too hard and expensive, it may be tempting to take short cuts.

Today, there are four common elements that point to weaknesses in our healthcare systems, which allow fraudsters to slip through the cracks and practise medicine.

1. Misplaced trust

Everyone believes someone, somewhere, has checked and verified a person’s credentials. But sometimes this hasn’t been done, or it takes a long time.

Fake psychiatrist Mohamed Shakeel Siddiqui—a qualified doctor who stole a real psychiatrist’s identity and worked in New Zealand for six months in 2015—left a complicated trail of identity theft that required the help of the FBI to unravel.

Last year, in Germany, a man was found to have forged foreign qualifications that he presented to the registering body in early 2016. He was issued with a temporary licence while these were checked. When the qualifications turned out to be fraudulent, he was fired from his job as a junior doctor in a psychiatric ward. But this wasn’t until June 2017.

2. Foreign credentials

Credentials from a foreign university, issued in a different language, are another common element among medical fraudsters. Verifying these can be time-consuming, so a health system desperate for staff may cut corners.

Ioannis Kastanis was appointed as head of medicine at Skyros Regional Hospital in Greece in 1999 with fake degrees from Sapienza University of Rome. The degrees were recognised and the certificates translated, but their authenticity was never checked.

Dusan Milosevic, who practised as a psychologist for ten years, registered in Victoria in 1998. He held bogus degrees from the University of Belgrade in Serbia—at the time a war-torn corner of Europe, which made verification difficult.

3. Regional and remote practice

It’s easier to get away with faking in regional or remote areas where there is less scrutiny. Desperation to retain staff may also silence complaints.

‘Dr’ Balaji Varatharaju fraudulently gained employment in remote Alice Springs, where he worked as a junior doctor for nine months.

Ioannis Kastanis had worked on a distant Greek island with a population of only around 3,000 people.

4. It’s not easy to dob

Finally, there are two unnerving questions. How do you tell a poorly trained but legally qualified practitioner from a faker? And who do you tell if you suspect something is off?

The people best placed to spot the fakes—other hospital and healthcare staff—work in often stressful conditions where complaints about colleagues can lead to reprisals. If the practitioner is from another ethnicity or culture, this adds an extra layer of sensitivity. It was only after ‘Dr Chitale’ was exposed that staff were willing to say his practice had been ‘shabby’, ‘unsavoury’ and ‘poor’.

So, why do they do it?

The reasons for fakery are as diverse as the fakers. ‘Dr Nick Delaney’, at Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital in Brisbane, reportedly pretended to be a doctor to ‘make friends’ and keep a fling going with a security guard at the same hospital.

On a more sinister level, there are possible sexually predatory reasons, like those of bogus gynaecologist Raffaele Di Paolo. Fake psychiatrist Mohamed Shakeel Siddiqui said he only did it to help people.

There are also the less easily understood fakers, like ‘Dr’ Adam Litwin, who worked as a resident in surgery at UCLA Medical Center in California for six months in 1999. Questions only began to be asked when he turned up to work in his white coat with a picture of himself silk-screened on it—even by Californian standards, this was going too far.

So how do we stop this happening?

Part of the problem is our cultural dependence on qualifications as the passkey to higher income and social status, making them an easy target for fraudsters. Qualifications only reduce risk, but they can’t eliminate it. Qualified doctors can also cause havoc: think Jayant Patel and other bona fide qualified practitioners who have been struck off for malpractice, mutilation and manslaughter.

Conversely, no one complained about ‘Dr Chitale’ in 11 years. The only complaints Kastanis received in 14 years were from people who thought his Ferrari was vulgar. The German junior doctor had an excellent knowledge of mental healthcare procedures and language—obtained from his time as a psychiatric patient.

Most of these loopholes can be closed with time and patience. What would help is if hospital and healthcare staff felt sufficiently supported to report their suspicions to their employer, rather than to their colleagues. This would foster a more open culture of flagging concerns about fellow practitioners without fear of formal or informal punishment. It might also uncover more ‘Dr Chitales’ before anyone is seriously harmed.

Article first published April 10, 2018.

Friday essay: The ‘great Australian silence’ 50 years on

Anna Clark

Australian Research Council Future Fellow, Australian Centre for Public History, University of Technology Sydney

It’s 50 years since the anthropologist W.E.H. Stanner gave the 1968 Boyer Lectures—a watershed moment for Australian history. Stanner argued that Australia’s sense of its past, its very collective memory, had been built on a state of forgetting, which couldn’t ‘be explained by absent-mindedness’:

It is a structural matter, a view from a window which has been carefully placed to exclude a whole quadrant of the landscape. What may well have begun as a simple forgetting of other possible views turned under habit and over time into something like a cult of forgetfulness practised on a national scale.

His lectures profoundly influenced historians partly because of the image he captured: for a practice based on documentation, archiving and storytelling, silence is a compelling idea. And a whole-scale silence—a ‘cult of forgetfulness’, no less—indicated a bold re-imagining of a national historiography on Stanner’s part.

As Stanner insisted, this sort of silence was no ‘absent-mindedness’: the occlusion of Aboriginal people from Australian history wasn’t inevitable.

In the wake of his lectures, influential Australian historians conceived of their own historical awakening in these same terms. In an autobiographical essay, historian Marilyn Lake described the prevailing historical view in her small rural town: ‘Growing up in the former colony of Tasmania we did our fair share of forgetting too.’ And in his evocative memoir, Why Weren’t We Told?, Henry Reynolds famously pondered that shift away from silence as people endeavoured to write in Indigenous perspectives from the 1970s onwards.

It’s a common refrain. I remember my dad describing how he also ‘hadn’t been told’ about Australia’s Aboriginal history when Reynolds’s book came out. And a colleague and friend recently recounted visiting Myall Creek as part of a Sunday school picnic in the 1980s: no-one mentioned its dark history as the site of an infamous Aboriginal massacre in 1838.

Yet the move from ‘great Australian silence’ to historical ‘truth-telling’ isn’t quite as clear-cut as Stanner’s description might suggest. ‘Too often it is taken to imply a kind of historiographical periodisation where there was no Aboriginal history before Stanner’s own lecture and an end to the silence after it,’ writes Ann Curthoys. Yet that doesn’t capture the whole picture: ‘there is neither complete silence before 1968, nor was it completely ended afterwards’.

While we now have important interventions into Aboriginal history that amplify Australia’s uncomfortable past, such as Lyndall Ryan’s massacre map and the Uluru Statement from the Heart, those reverberations continue to cause anxiety.

The Statement from the Heart called for a ‘truth-telling about our history’ but still awaits bipartisan support. Meanwhile, online commentary in response to the release of Ryan’s massacre database shows the persistence of historical refusal in Australia.

‘Black crows’

The ‘great Australian silence’ is also historically a little more complex. I’m writing a history of history-making in Australia and have been struck by the detailed interest in Aboriginal life as well as the often graphic accounts of frontier violence in works from the early and mid-19th century. For want of colonial history ‘texts’, I’ve also been reading travelogues and emigrants’ guides. While these books and pamphlets are largely observational, they frequently present historical narratives and interpretation.

Many of them didn’t hold back in their tales from the colonial frontier, cataloguing extensive episodes of violent conflict between Aboriginal people and colonialists.

Have a look at this description of the 1838 Myall Creek massacre from Godfrey Charles Mundy in his travelogue, Our Australian Antipodes, published in 1852:

They captured the whole of them, with the exception of a child or two; and having bound them together with thongs, fired into the mass until the entire tribe, 27 in number, were killed or mortally wounded. The white savages then chopped in pieces their victims, and threw them, some yet living, on a large fire; a detachment of the stockmen remaining for several days on the spot to complete the destruction of the bodies.

It is graphic historical writing.

The horror of Mundy’s Myall Creek account is paradoxically eclipsed by the chilling official silence he observes after most attacks:

Reprisals [against Aboriginal people] are undertaken on a large scale—a scale that either never reaches the ears of the Government, which is bound to protect alike the white and the black subject; or, if it reaches them at all, finds them conveniently deaf.

James Demark’s Adventures in Australia Fifty Years Ago, from 1893, similarly reports a structural and deliberate deafness in response to the violent, eerie echoes across the frontier: ‘The settlers retaliated in their own way’, he writes, and ‘there were no Government regulations to check these irregular proceedings’.

Even self-described histories, such as those by James Bonwick and John West, explicitly link frontier violence with Australia’s colonisation. West’s History of Tasmania, first published in 1852, even uses the terms ‘black hunts’ and ‘black war’ to describe the first 50 years of Van Diemen’s Land. West was an abolitionist, and a tone of historical injustice inflects his writing about the Tasmanian Aborigines in volume 2.

Take this excerpt, where he relates the perverse logic of colonial expansion:

It was better that the blacks should die, than that they should stain the settler’s heath with the blood of his children.

And this one, where he mourns the destruction of Tasmanian Aboriginal society in only two generations:

At length the secret comes out: the tribe which welcomed the first settler with shouts and dancing, or at worst looked on with indifference, has ceased to live.

Bonwick’s 1870 history of Tasmania is similarly full of sentiment. In a tone curiously analogous to Paul Keating’s Redfern Park speech 120 years later, Bonwick offers this lament on the effects of colonisation on Tasmania’s Aboriginal people:

We came upon them as evil genii, and blasted them with the breath of our presence. We broke up their home circles. We arrested their laughing corrobory. We turned their song into weeping, and their mirth to sadness.

Bonwick also reveals the ease with which colonial discourse accounted for murder. During his time in Tasmania, Bonwick writes, he had heard several people explain that ‘they thought no more of shooting a Black than bringing down a bird’. He went on:

Indeed, in those distant times, it was common enough to hear men talk of the number of black crows they had destroyed.

Those recollections of euphemistic colonial vernacular hint at some of Bonwick’s method as a historian. In the introduction to his history and in an 1895 talk to the Royal Colonial Institute in London, he gives a more detailed explanation of that approach.

It was not a hunt through ‘blue books’ (government records), that provided the source material for his research, he explains. Rather, it was conversation and hearsay, from sly-grog sellers, ex-bushrangers and colonial gentry alike, that furnish his historical narrative.

How else could you write about hunting crows?

Alongside those histories was a humanitarian public discourse that anguished over frontier violence. Media commentary, public debates and lectures, as well as letters to the editor from the frontier that related specific episodes of violence, are explored in detail by Henry Reynolds in This Whispering in Our Hearts.

Likewise, poetry such as The Aboriginal Mother (1838) by Eliza Hamilton Dunlop reveals a form of popular and creative history-making in response to colonisation that can be seen in the work of writers such as Judith Wright and Eleanor Dark a century later.

So why was that reverberation replaced with euphemism and omission? Partly the silence was a fear of punishment, as Bain Attwood argues in a recent essay on historical denial.

Especially after the successful prosecution of the Myall Creek massacre perpetrators, colonial front lines and allegiances became a little murkier. ‘There were good reasons to be silent,’ historian Tom Griffiths has similarly insisted.

Mundy’s 1852 account of his ‘ramble’ through the Antipodes confirms Attwood’s and Griffiths’ explanation, and reveals how stories quietly murmured along the frontier provided a catalogue of violence. He writes:

Dreadful tales of cold-blooded carnage have found their way into print, or are whispered about in the provinces. And although there be Crown land commissioners, police magistrates, and settlers of mark, who deny, qualify, or ignore these wholesale massacres of the black population, there can be no real doubt their extirpation from the land is rapidly going on.

‘Historia nullius’

It wasn’t simply a case of an uncomfortable frontier that came to characterise the silence Stanner identified in his Boyer Lectures, however.

The historians Stanner named in his lectures (such as M. Barnard Eldershaw, Hartley Grattan, Max Crawford and Brian Fitzpatrick) were largely silent on Aboriginal policy and history in their mid-20th-century histories—despite being written after the 1930s, a decade that Stanner notes for its influence in shapeshifting on Aboriginal policy.

Yet this form of history writing had begun in the late 19th century. At a time when Australian nationhood and national identity were being formed around Federation, the historical discipline was moving into a particular form of narrative writing oriented towards (non-Indigenous) Australian exceptionalism based on democratic and economic progress.

As Australia’s national consciousness emerged, it required a historical consciousness of its own origin. Education departments commissioned history texts and universities appointed history professors. As history became increasingly professionalised, ‘blue books’ and official archives were in; hearsay and poetry out.

So what did disciplinary ‘silence’ look like in Australia? It saw History (with a capital ‘H’) arriving with colonisation: ‘She alone of all the continents has no history,’ proclaimed journalist Flora Shaw in a presentation about Australia to the Royal Colonial Institute in London in 1894:

She offers the introductory chapter of a new history and bases her claim to the attention of the world upon the future which she is shaping for herself.

Lorenzo Veracini has described that settler–colonial vision of the Australian continent as a sort of historia nullius, where ‘Australian history’ only existed thanks to the selective creation and curation by colonial historians.

For Australian historians in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the silence of pre- and post-contact Indigenous experience occurred because it existed outside the Whiggish historical narrative of imperial progress. ‘The federation of (white) Australia and the birth of ‘national’ historical consciousness thus represent … a moment of disciplinary origin,’ historian Leigh Boucher asserts.

In his 1916 Short History of Australia, Ernest Scott described ‘vast tracts of fertile country which had never rung under the hoof of a horse and where the bleat of a sheep had never been heard’. In these texts, silence is counterposed against the ringing of axes and ‘industry’.

Scott writes that Australia ‘begins with a blank space on the map, and ends with the record of a new name on the map, that of Anzac’. It’s worth dissecting this quote here, to unpack that form of history writing: the inevitability of historical progress and national formation is telling.

We shouldn’t assume that this early national history writing was completely silent on Indigenous matters. Coghlan and Ewing’s 1902 Progress of Australasia in the Nineteenth Century described the ‘invasion’ of parts of southern Australia by the colonists, and related in some detail the colonial massacre of Aboriginal people at Risden Cove in Tasmania; and Scott’s 1916 short history included ghastly and violent accounts of murder on the colonial frontier, as well as the deliberate planting of arsenic in flour destined for Aboriginal people.

Nevertheless, Stanner gave voice to an emergent idea about silence that understands history as a method that changes over time and place, rather than an objective interpretation of the past. It reminds me of what narrative psychologist Jerome Bruner explains as the ‘coherence’ we ‘impose’ on the past, to ‘make it into history’.

In other words, the 1930s histories that Stanner identified in his Boyer Lectures exist in a historical structure where Indigenous perspectives have been locked out. As Stanner himself articulated:

We have been able for so long to disremember the Aborigines that we are now hard put to keep them in mind even when we most want to do so.

Still a work in progress

Stanner’s point raises an important question: if ‘History’ itself is tied to the process of colonisation, can it accommodate perspectives outside its colonial apparatus? Stanner sensed that history would overcome its own silences, but doing so would require major methodological shifts, such as the incorporation of Aboriginal Studies and oral history:

In Aboriginal Australia there is an oral history which is providing these people with a coherent principle of explanation … It has a directness and a candour which cut like a knife through most of what we say and write.

His predictions played out, and such approaches, applied by Indigenous and non-Indigenous historians such as Hobbles Danyari, Heather Goodall, Peter Read, Paddy Roe and Deborah Bird Rose, overturned Aboriginal historiography in Australia.

The murmurings have since turned into a groundswell: Indigenous histories have become increasingly prominent and Indigenous perspectives are now mandated across school curricula. Conspicuous public and political debates over Australian history are further indication of how this counter narrative has become a significant historical lens.

‘I hardly think that what I have called “the great Australian silence” will survive the research that is now in course,’ Stanner anticipated. And, to a large degree, he was right—a substantial historical revision has taken place in Australia.

If anything, that change has accelerated since Stanner’s death in 1981. Yet in university history departments Indigenous historians still remain vastly under-represented.

Indigenous perspectives have increasingly informed, critiqued and revised historical approaches. But Indigenous histories are often relegated to ‘memoir’, ‘story’, ‘family history’, ‘narratives of place’ or ‘political protest’, rather than acknowledged as part of a disciplinary practice.

And with the possible exception of oral history and pre-history/deep time, there is still a marked absence of Indigenous historiography in Australia’s historical ‘canon’.

We may have developed new critical approaches and a growing understanding of the genealogy of historical ‘silence’. Yet the meaning and the consequences of that understanding are still a work in progress.

Article first published August 3, 2018.

Time to honour a historical legend: 50 years since the discovery of Mungo Lady

Jim Bowler

Professorial Fellow, School of Earth Sciences, University of Melbourne

This month we celebrate an event 50 years ago in western New South Wales that changed the course of Australian history. On July 15, 1968, the discovery of burnt bones on a remote shoreline of an unnamed lake basin began a story, the consequences of which remain sadly unfinished today.

It’s the story of a legend, the discovery of Mungo Lady, the first in the series of steps that led to the creation of the Willandra Lakes World Heritage area.

But it’s a story where the making of a legend has fallen off the national radar, leaving a legacy of shame.

At a time when we afford so much effort to remember those in Australia’s more recent history, is it not time to honour those who helped tell so much of the ancient history of our land?

A timely discovery

It was just one year after the circuit-breaking 1967 referendum. Aboriginal people were being heard.

For me it was the beginning of a journey to explore the geological legacy of climatic change in our ice age landscapes, the ancient dunes, lakes and rivers.

I had recently joined the Australian National University Department of Geography and had chosen dry lake basins as possible rain gauges for ancient wet climates.

I was mapping ancient shorelines and finding strange objects, freshwater shells high above water levels, stone tools lying on erosion surfaces, fallen from above but with no certainty of their original undisturbed sites. People had been there long before me.

I reported my suspicions of ancient shoreline occupation of this now-dry basin to archaeological colleagues at the Australian National University. I later named the basin Lake Mungo, after the pastoral property lease that covered the major part of the basin, Mungo Station.

From geological analysis I was confident the lakeshore dune suggested origins at least 20,000 years ago. My archaeological colleagues immediately dismissed this with the warning: ‘Bowler, geologists should stick to stones. Leave the archaeology to us.’ That warning never anticipated the finding of bones in lakeshore stones.

Concerned to resolve the puzzle, I was studying freshwater shells deep in the dune core of this ancient lake margin. According to my field notes that was on July 15, 1968, although it was incorrectly reported for a time as July 5.

If those shells represented a human midden (a refuse heap), it involved occupation much older than accepted at the time. But was it human agency? Birds can carry shells.

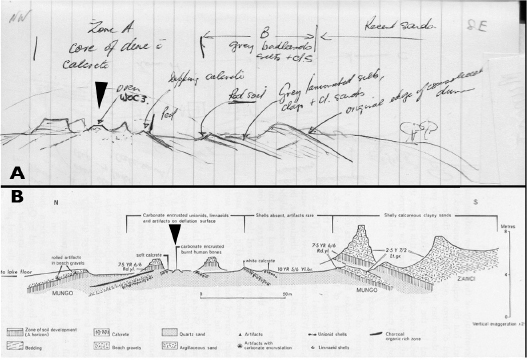

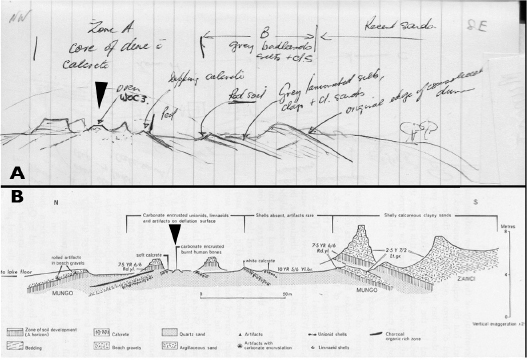

Diagrammatic cross-section through the site of suspected hearth, later identified as cremation site of Mungo I, arrowed.

Source A (upper): Sketch from field notes of July 15, 1968.

Source B (lower): Details published in proceedings of the 1968-69 seminars (Aboriginal Man and Environment in Australia, Eds. Derek John Mulvaney & Jack Golson, 1971. ANU Press, p.389).

Burnt bones uncovered

Returning to camp in the late afternoon, an interesting block of soil carbonate lay exposed on an erosion surface. Nothing special in itself, but this contained a substantial concentration of burnt bones.

Firmly cemented in soil carbonate, this reflected a fire of great antiquity. The organised burning of large mammalian bones, recorded in field notes as a probable hearth, clearly involved human agency. Ironically, this was the first item of archaeological evidence clearly in an undisturbed position.

Duly marked for future location, I reported these findings in an October 1968 archaeological seminar at the ANU. The photographs shown then of burnt bones of such obvious antiquity spoke for themselves.

The scepticism of my archaeological colleagues diminished. Despite an immediate invitation, it took another six months, until March 1969, to lead a team of soil scientists and archaeologists to the site.

Finding the bones exactly as I had left them eight months earlier, that clear sunny day generated immense excitement. Dr Rhys Jones, breaking away fragments of cemented bones, recognised remnants of a human cranium.

Suddenly, this was not just the reflection of human activity. We were in the presence of humanity itself. Australian archaeology took a leap forward!

A very modern human from many years ago

Collected into Professor John Mulvaney’s suitcase, the bones were delivered in Canberra to Dr Alan Thorne, the ANU physical anthropologist. His meticulous cranium reconstruction demonstrated the remains of a fully modern young woman.

Dated by later work to 40,000 years ago, that small modern cranium had impacts far beyond its size. It remains today as the world’s earliest evidence of cremation.

It brought to a close the long and, to Indigenous peoples, the offensive practice of cranial profiling, the measure used to test differences between ancient and modern cranial features.

Following its earliest introduction by Thomas Huxley in 1863—a man known as Charles Darwin’s ‘bulldog’—the gathering of Aboriginal skeletal remains became a virtual industry. Grave robbers competed to supply university anatomy departments and museums around the world.

Alone, but now announced on the international stage, Mungo Lady’s clearly modern cranium brought it to an end. At 40,000 years ago, she was just like us!

Mixed blessings

To Aboriginal Australians, the removal of bones and the Thorne reconstruction brought mixed blessings.

Firstly, removal of remains without permission evoked memories of more grave robbing. For a time, cross-cultural tensions developed between scientific and Indigenous cultures.

Some nine years later, friendly dialogue led to the signing of an historical accord, a collaborative agreement between the two groups—scientists and traditional owners—each learning from the other. That agreement holds to the present day.

Secondly, Mungo Lady’s voice, declaring her rightful place in this landscape, stirred Aboriginal women into action, especially traditional owners among the three tribal groups—Mutthi Mutthi, Barkindji and Ngiyampaa.

As though by canonisation, she became a saintly figure, especially to the central pioneering elder, the late Alice Kelly, together with her companions from related tribal groups, Alice Bugmy, Tibby Briar and Elsie Jones.

These four pioneering women stood together to assert Aboriginal ownership, to challenge the bureaucracy and ensure the legacy of Mungo Lady held pride of place in the history of Australia’s occupation.

Sadly, that resolve has been betrayed. The story of her heritage management is no less than disaster.

The remains today

Returned to traditional owners by Alan Thorne in 1992, the skeletal remains of this legendary person lie today in anonymous solitude with those of the later discovery, Mungo Man, out of sight and out of mind in storage at Lake Mungo visitor precinct. No monument, no place for respectful gratitude, no place to honour.

In late 2013, the NSW government, without warning, summarily dismissed all management structures, Central Management, the Elders Council and the scientific advisory group. For the last four years, there has been no management in place, no one to care.

A costly new plan of management was delivered by consultancy in early 2014, but there remains, even today, no management group to give it to. The governments of both NSW and Australia have turned their backs on this legendary issue.

Traditional owners, scientists and the Australian public have been deprived of that fundamental right to honour the dead to whom our history owes so much.

But the nation owes a special debt to this ancient lady. In death, together with her Aboriginal women pioneers, she has changed the way we see ourselves across the cultural divide.

Time to honour a lady

So a message for Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull: A$100 million appeared no problem for that worthy Monash memorial to our dead in France.

It’s time now to cut through the tangled web of bureaucratic inertia, to bring the remains of those legendary Mungo figures, Mungo Lady and Mungo Man, from storage to a central place of honour.

The nation needs a vision, the inspiration to build the contemplative space where stories of ice age land and ice age people join to illuminate what it means to be Australian.

The Willandra Lakes World Heritage area provides the place. To do less adds additional shame to an already failed heritage trust.

Article first published July 6, 2018.