April 13, 1966: Boeing sells the first 747 jets to Pan Am.

July 2, 1966: France tests the A-bomb on Mururoa.

June 17, 1967: China tests its first H-bomb.

JANUARY 23, 1968: THE USS PUEBLO IS CAPTURED BY NORTH KOREA.

March 16, 1968: The My Lai Massacre takes place, Vietnam.

June 6, 1968: Robert Kennedy is shot in Los Angeles.

January 12, 1970: The Boeing 747 takes its maiden flight.

O it’s broken the lock and splintered the door,

O it’s the gate where they’re turning, turning;

Their boots are heavy on the floor

And their eyes are burning.

—W. H. AUDEN, “O WHAT IS THAT SOUND?”

One crisp, cold winter’s day in 1968, men with burning eyes fired their heavy machine guns on a small, dilapidated, and barely armed American warship and managed, by doing so, to bring Washington swiftly to its knees.

The men were North Koreans, and the actions they commenced shortly after noon on Tuesday, January 23, culminated in the capture of the ship, a 335-ton army freighter turned floating electronic eavesdropper named USS Pueblo. The ship’s seizure resulted in one of the most calamitous intelligence debacles the United States had ever suffered, and it was the first time an American naval vessel had been seized on the high seas since the British captured the frigate USS President off the coast of New York City in 1815, more than a century and a half before. But whereas the President’s crew was merely imprisoned in Bermuda and then sent home, the Pueblo’s eighty-two surviving sailors were starved and tortured for the better part of a year, until the American government was compelled to make a craven apology in order to have the half-broken men set free.

The humiliation caused by this incident was total, deliberate, and public. It was also entirely in keeping with the long-standing behavior patterns of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea, in its formal English-language rendering) toward the United States and its allies in this corner of the western Pacific. The Pueblo incident was just one of hundreds of taunting provocations, some of them lethal, some profoundly dangerous, others ludicrously extravagant, but most of them merely annoying, that have taken place since the ill-tempered signing of an armistice agreement marking the end of the Korean War’s formal hostilities in July 1953. No peace treaty has ever been enacted between the various sides in that brutal three-year brawl: the 1953 agreement merely established rules meant to prevent the resumption of armed hostilities. Considering that today the principal parties have atomic weapons, these rules seem more necessary than ever.

The roots of the nuisance—and although harsher words can easily be used to describe the pariah state of North Korea, its purely military significance in the Pacific theater, even with its atomic warheads, is reckoned to be little more than a wretched annoyance—lie deeper still than the 1953 armistice. And they are entirely the result of a single hurried decision, by just one man, with just one map, that brought about the division of the Korean Peninsula. And both the man and the map were decidedly American.

The map was a large, wall-mounted, small-scale (552 miles to the inch at the equator), National Geographic Society map of the Pacific Ocean. It had been designed by the society’s legendary chief cartographer, Albert Bumstead, and its photo lettering was designed by the equally famed typographer Charles Riddiford. The map was pinned up in the Pentagon office of George Marshall, who was then the army chief of staff, and who had used it to plan the movements of American forces in and around the ocean.

In Washington it was nighttime on August 14, 1945. Five days before, the second atomic bomb had been dropped, with devastating effect, on Nagasaki, and Emperor Hirohito, in his thin, reedy, and hitherto publicly unheard voice, was on Japanese radio telling his people that the fighting was now over and that Japan would surrender, bringing the war in the Pacific to an end.

Those listening in the Pentagon were relieved and satisfied, though it was a satisfaction muted by the sober realization that their supposed allies and friends, the Soviets, were now scything their way fast and furiously past the defeated Japanese units in Manchuria, on Sakhalin Island, and into Korea. And as the Communist Russians did so, they were claiming immense new tracts of territory. Fear about the long-term implications of this land grab dampened any celebration inside the Pentagon.

The Cold War had not yet begun,* but already strategists in Washington were supposing, correctly, that the Communists had ambitions to mop up territories for themselves along the Pacific periphery.

Marshall’s staff officers decided that night that they must come up with immediate recommendations—for the White House, for the Joint Chiefs of Staff—for halting the Soviets’ advance. They first decided to establish a series of checkpoints around the region where the onrushing expansion might be stopped. One of these young officers then walked over to the wall map and pointed to the scantily known and, of late, Japanese-governed peninsula of Korea.

The officer was thirty-six-year-old Colonel Charles Hartwell Bonesteel III, a third-generation soldier, a West Point graduate, and a Rhodes Scholar. Standing before the blue-washed expanses of the National Geographic map, he traced his index finger east and west across the entire breadth of the ocean, along a line of latitude that almost precisely joined the cities of San Francisco and the Korean capital, Seoul. Both of them lay some thirty-seven and a half degrees north of the equator, he observed—an uncanny coincidence.

He promptly declared that it was important for the city of Seoul, Korea’s capital, to remain in American hands. He told his two colleagues in the room—one of whom, Dean Rusk, would become President Kennedy’s secretary of state—that the Soviet army should be requested to stop its advance just north of the capital. Since Seoul lay at thirty-seven and a half degrees, then “the Thirty-Eighth Parallel should do it,” Bonesteel remarked with studied casualness. Then, using a grease pencil, he promptly drew a line clear across the map, from Asia to California, along the latitude line thirty-eight degrees north of the equator. The officers told General Marshall what they recommended.

Born into an esteemed American soldiering family, Colonel Charles Bonesteel III—seen here after eye surgery—famously drew the line in August 1945 that divided the Korean Peninsula along the Thirty-Eighth Parallel, creating North Korea.

U.S. Army.

Marshall thought the latitude line was perfectly reasonable and logical. Diplomats were told, and within hours, Moscow, to the astonishment of all, Teletyped back the Soviets’ concurrence. The Red Army would continue its sweep down into Korea, the message said, and would accept the surrender of all those Japanese forces on the peninsula stationed to the north of the Thirty-Eighth Parallel. The United States could land its troops elsewhere, and confront the Japanese occupiers to this line’s immediate south.

This was all written swiftly into General Order No. 1, the surrender demand that was handed formally to the Japanese the very next day. The two relevant paragraphs of this historic document were the second (“The senior Japanese commanders and all ground, sea, air and auxiliary forces within Manchuria, Korea north of 38 north latitude and Karafuto shall surrender to the Commander in Chief of Soviet Forces in the Far East”) and the fifth (“The Imperial General Headquarters, its senior commanders, and all ground, sea, air and auxiliary forces in the main islands of Japan, minor islands adjacent thereto, Korea south of 38 north latitude, and the Philippines shall surrender to the Commander in Chief, U. S. Army Forces in the Pacific”).

Immediately, and with this succinct command, two quite new and separate spheres of influence were created in the world. One would in time come to be called South Korea, and would fall under the general influence of the Americans; and the second, known as North Korea, would come under the influence and direction, first, of the Soviets and, later, of the Chinese Communists.

In due course the latter would become the oxymoronically named Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. Within a decade, these two separate, distinct, and mutually hostile states would be riven by a disastrous three-year war, which would reach an uneasy conclusion in 1953 that has separated them ever since by the most dangerous and heavily armed international border on the planet.

Many military strategists have speculated that the world might have been a far safer place if postwar Korea had been divided four ways, among the United States, the Soviet Union, the Republic of China, and the United Kingdom, as was first proposed. Or if the Soviets had been given free rein to invade all of Korea, and be done with it. In this latter instance, there would have been no Korean War, for certain—merely a Leninist satrapy in the Far East that, most probably, would have withered and died, as did other Soviet satellite states.

Instead, the Pacific Ocean’s most volatile choke point was created, innocently and unthinkingly, by one swift sweep of a grease pencil held by Charles Hartwell Bonesteel III, a man who had been known since childhood by the nickname Tick. Like so many other all-too-swift border creations—the one between India and Pakistan comes to mind—his would leave a legacy both unimagined and unimaginable. Bonesteel would live until 1977 and would see the many consequences of his casual defacement of that National Geographic map, not least the horrendously lethal war that erupted five years later, and then the thousands of subsequent cross-border shootings, kidnappings, incursions, tunneling, and myriad other nuisances for which the Thirty-Eighth Parallel is still known today—one of the most egregious being the capture in 1968 of the U.S. Navy spy ship USS Pueblo.

This shabby little ship, a vessel akin more to the USS Caine than to the USS Constitution, was part of a secret navy spying program of the 1950s named Operation Clickbeetle. Initially the plan was supposed to involve the recruitment of as many as seventy similarly elderly, clapped-out, and inexpensive vessels, most of them deemed useless for anything more than being melted down and made into razor blades. They were to be stuffed to the gills with electronic espionage apparatus and ordered to hug the coastlines of countries that Washington thought were troublesome, told to run out their aerials and to listen to radio chatter. But the budget couldn’t stretch to seventy ships, and in the end the Pentagon got only three, the USS Palm Beach, the USS Banner, and the USS Pueblo.

This last was the mothballed runt of the litter, and she was handed the trickiest assignment of the trio. She was to be the eyes and ears in the far western Pacific for the National Security Agency (NSA), then as now the most secret of all major American espionage organizations.

Though nothing like the omnivorous Gargantua of electronic spying it is today, the NSA in 1968 was nonetheless an immense, powerful, and expensive agency. I remember all too well being shooed away by guards when I drove too close to its triple-fenced compound in Fort Meade, Maryland. It also had secret and well-guarded outstations around the globe, from which I was also turned away whenever I tried to visit. Some were static—in Britain, in Hong Kong, on Ascension Island, in Gibraltar, on Hawaii, on Diego Garcia. Others were mobile: airborne or seaborne; some of the latter were submarines. Still others, such as the three starveling ships of Operation Clickbeetle, rode the surface waters, always isolated from other vessels, their role in espionage publicly denied, their official capacity spoken about as softly as their budget requests were hidden, even though their tasks were seen as crucial to the fast-growing empire of intelligence gathering.

The tugboat-size Pueblo, which had a couple of small tarp-covered, downward-pointing machine guns on deck under a canvas awning that made her look more like a Pacific islands tramp steamer than a fighting vessel, was supposedly, ostensibly, officially conducting innocent oceanographic research. Improbably, and in an attempt to bolster the vessel’s cover story, a college professor of nutrition was on hand at the commissioning ceremony in the Port of Bremerton, in Washington State, to tell reporters that the Pueblo’s work might involve extracting new high-tech foodstuffs from oceanic waters. This was still, after all, the time of TV dinners, and people liked to believe such things.

The Pueblo’s chosen commander was to be a hard-drinking, fast-talking, loud, chess-playing, Shakespeare-loving muscleman and former submariner named Lloyd Bucher (Pete to his friends). Bucher was initially disappointed that he was being given command of such an undistinguished vessel. But he changed his mind after ten days of briefings at the Pentagon and at Fort Meade. This was because his little ship, which would be homeported in Japan, was not going to work along the stoutly defended coasts of the Soviet Union or China. Instead, she would venture out northwestward, across the six hundred miles of the Sea of Japan, and patrol along the little-known coastline of North Korea, a ragged line never less than thirteen miles from shore—twelve miles being the territorial limit declared by most Communist nations of the time. From there she would intercept, listen to, and decipher all the radio transmissions and other electronic chatter that emanated from this most secretive of Asian states.

Built on Lake Michigan in 1944 as an army freighter and transferred to the U.S. Navy as an environmental research vessel, the USS Pueblo was captured by North Korea in 1968 while on a spy mission. She remains captive, as a museum.

U.S. Navy.

It was all very hush-hush, considered by Washington to be of critical importance. This, coupled with Bucher’s understanding that he would be performing his work all alone, and that the full might of the U.S. Navy in the Pacific might well not be able to reach him should he ever get himself into trouble, thrilled the young captain’s gung-ho side. He was a man eternally eager for adventure, a show-off notoriously given to braggadocio and fond of derring-do.

There was at the time a rough-and-ready code applying to the Cold War’s spy ships, born partly of the belief among naval officers that the sea is the only true enemy, and that human arguments are subordinate to the sea’s dangers and demands. So there was at the time, for instance, a gentleman’s agreement that governed spying on the Soviet Union, each side accepting that espionage was a necessary evil, and therefore tolerating the fact that ships involved in such business were deployed by the other’s navy. But Bucher was rather more fascinated to be told, and most forcefully, that no such agreement covered espionage against North Korea. True, Pyongyang was perhaps less of a threat. Its navy was small, with just a number of small coastal craft, and it had no blue-water ships of the kind operated by Moscow. But the North Koreans could be nasty and dangerous; moreover, they played outside the rules. This also thrilled Bucher, who was entirely undaunted by the dangers. So he flew off to his ship’s fitting-out in Washington State wholly excited by his coming duties.

It was in Bremerton that the highly sensitive interception equipment (to be manned by technicians who worked in code-locked cabins) was installed on the ship and tested by NSA engineers. Dozens of radio aerials and radar dishes, some familiar, others ungainly and of strange shape, were mounted all over the ship, most of them sprouting from two high masts built amidships. Once this work was completed, Bucher was ordered to sail his technologically festooned little craft (which rolled mercilessly on the ocean swells, to the crew’s discomfort and chagrin, causing Bucher to wonder if all the added gear might make the boat dangerously top-heavy) across to Hawaii. There, he would be given further secret and more specific briefings by the chiefs of the Pacific Fleet. At the end of 1967, the Pueblo finally set off for the naval station at the Japanese port of Yokosuka, on the western side of Tokyo Bay, where she would be based and from where she would eventually commence her duties.

On January 5, 1968, after spending the Christmas holidays of 1967 in port, the tiny vessel, a plague of mechanical problems all half-resolved, headed out for what would be her first real-world operation. The forecasters said the temperature would be cold, the sea state moderate.* A number of North Korean trawlers were noted to be operating in the region where the Pueblo would be patrolling, but Bucher was reassured by his commanders that they would be likely to do no more than pester a sovereign ship of the U.S. Navy.

The presailing orders had been quite specific: the Pueblo was to spend two weeks sailing up and down the North Korean coast from the frontier with the Soviet Union down to the DMZ that marked the border with South Korea. She was to be on the lookout for two things: a series of newly built coastal antiaircraft batteries that America believed the North Koreans had been constructing, and any of four new submarines that Moscow had recently handed over to the North’s fledgling navy. After two weeks of this, the ship was to turn about and head back to Japan. For the entire journey, the Pueblo was to keep strict radio silence, except in the event of a real emergency.

Bucher clearly relished the instructions. He eased away from the dock and out into the fairway, and as he set sail on a southbound course he stood ostentatiously out on the Pueblo’s flying bridge. He was in fine, exuberant form: as his men toasted him with eggnog, he decided to show off his singing talents, booming down to them, and to all the mystified crews of passing Japanese fishing boats, a jazz number popular at the time, “The Lonely Bull.” It turned out to be an apposite choice.

After a storm-tossed but otherwise uneventful crossing, the Pueblo arrived off the North Korean port of Wonsan on January 13, and began her ferreting duties. As ordered, she kept well away from the coast, and to minimize her chances of being seen, she sailed dangerously through the nights with all her lights dimmed or doused. As instructed, she also maintained her radio silence, and with religious determination. Bucher would not even transmit the brief coded messages that all other American vessels sent daily, allowing Pacific Fleet headquarters to know where all its ships were, all the time.

The crew, alone and unleashed from authority, then fell into a simple patrol routine. With North Korea lying gray and cold and mountainous off to their west, and the Sea of Japan lying gray and cold and empty off to their east, there commenced a plodding sameness to every day: a lumbering, swell-tossed progress up and down the coast, the ship’s bristle of aerials listening out for any transmissions, the sailors’ watching eyes trained for anything unusual that might be observed. Other than that, a good deal of time was spent in the hammock, eating three plain meals a day, watching movies such as Twelve Angry Men and In Like Flint, and doing secret work for the codebreakers and the monitoring teams locked behind their blast-proof door with all their mysterious NSA machinery. The only work that kept the men physically active was chipping away ice from the superstructure. Bucher was worried that his already unstable ship could well founder if too much ice accumulated. This was work that all of them loathed.

Nine days of this zigzagging back and forth off the frigid Korean coast, and they were off the port of Wonsan once again on January 22, a Monday. Bucher and his crew had every reason to suppose that this day and the next would be as routine and as dull as the nine before. What they did not realize, because no one had seen fit to tell them, was that a series of events had unfolded on land the previous weekend that made their presence so close to North Korean waters particularly dangerous.

A heavily armed North Korean commando unit had been smuggled south of the border a week previously, with orders to mount a daring raid on the presidential palace in Seoul. The plan had been to execute the South Korean president, Park Chung Hee, to kill his family and personal staff, and to flee back across the border. Thirty-one tough young members of the 124th Army Unit, a North Korean special forces team, had cut their way through the fences, and then managed to get all the way into Seoul and to within half a mile of the palace, before being intercepted.

A massive weekend firefight had taken place on the capital’s streets, watched with amazement and horror by civilian city dwellers. The surviving North Korean commandos fled into the surrounding hills, and were picked off one by one by some of the six thousand South Korean troops who had been mobilized to find them. Come Monday morning the team from the North had all been killed, and the episode was all but over. But the atmosphere was still electric, and incredibly tense—and it is almost impossible to believe that no one at U.S. Pacific Fleet headquarters bothered to tell the Pueblo that its presence so close to North Korean waters was likely to be even less welcome than normal.

That Monday morning was uneventful and peaceful for the ship. Just after lunch, however, Captain Bucher was summoned to the bridge. Two North Korean trawlers had been spotted steaming toward them, and they were closing in fast. The craft halted less than twenty-five yards from the American ship, and their crew members, armed with more cameras than ordinary fishermen might need, took scores of photographs. The men had extremely fierce expressions. One Pueblo sailor remarked that “they looked like they wanted to eat our livers.”

An alarmed Bucher, deciding to break radio silence, told Japanese Fleet HQ that his ship had been identified. It took the better part of half a day to compose the heavily encrypted message and then send it on the one secret channel available to the ship.

Nothing more happened that day: the two trawlers left and headed back to shore. The next morning, only an unusual amount of North Korean coastal radio chatter suggested anything abnormal; as on Monday, the morning seas were quite empty, and the Pueblo, stopped dead in the water fifteen miles off the coast, seemed to be alone in the ocean. Then, around lunchtime, a small North Korean naval vessel, a lightly armed submarine chaser, suddenly appeared out of nowhere, heading toward the Pueblo at what American sailors call flank speed, the highest its engines could command. Its crew, all wearing helmets, raised signal flags, one after another: “What nationality?” demanded the first. “Heave to or I will fire” was the second.

The oncoming ship then radioed a flotilla of other fast patrol boats that were appearing over the horizon. “It is U.S. Did you get it? It looks like it’s armed now. It looks like it’s a radar ship. It also has radio antennae. It has a lot of antennae and, looking at the wavelength, I think it’s a ship used for detecting something.” This particular message—intelligent, articulate, savvy, but unheard aboard the Pueblo—happened to be intercepted by an American C-130 Hercules aircraft that was operating high above the North Korean coast as a direct consequence of the failed attack on the palace in Seoul three days before. The U.S. Air Force signals officer, alarmed by a drama that suddenly seemed to be enveloping an unwitting American ship far below, radioed promptly back to Japan, urging the staff there to warn the ship’s captain of what now seemed about to happen.

But if a signal was then sent to the Pueblo, it went unheard. A number of North Korean ships—six in total, summoned by the subchaser’s first broadcast, and now appearing from all corners of the compass—were closing in on the Pueblo, fast. Only twenty minutes had passed since the first ship was seen, and now heavily armed enemy vessels were everywhere. They had clear intentions. “We will close down the radio, tie up the personnel, tow it and enter the port at Wonsan,” said the subchaser to one of her sister ships. “We are on the way to boarding.”

Bucher, aware only of the presence of a flotilla closing around him, quickly considered his limited options. He might try to outrun his pursuers, or else he might scuttle his ship, destroying secret documents. Two MiG jets then flew low overhead, adding to the gathering drama.

The U.S. captain decided on defiance. He first ran up signal flags indicating he was staying put—he was, after all, officially an oceanographic ship, collecting water samples. But within moments, a number of North Korean sailors appeared on the deck of the subchaser, all of them armed with rifles and clearly readying themselves to board the American vessel. So, beginning to sweat, Bucher ordered his signalman to put out more flags, this time spelling out a more conciliatory message: “Thanks for your consideration—I am leaving the area.” He pointed his prow eastward, spooled up his engines, first to two-thirds ahead and then to full speed, and lit out for the open sea. He was trying to leave with dispatch and dignity, he later said.

Up above, the American aircraft heard, quite distinctly, an alarming radio call from the North Korean subchaser: “They saw us, and they keep running away. Shall I shoot them?” Orders were evidently given from an unseen controller ashore, because Bucher then spotted a fresh set of signal pennants going up on the ship that was now half a mile behind him: it was the same warning—“Heave to or I will fire.” But he decided to keep on running. He ordered his crew to destroy as much secret material as possible, to smash the electronics, to burn the paperwork. He doubted he’d have much time.

He heard the jets thunder past overhead once again, this time terrifyingly low, terrifyingly loud. The smaller North Korean patrol vessels broke away, leaving the Pueblo alone, firmly in the gun sights of the pursuing capital ship. Then, with a terrible fusillade of sound and smoke and flying lead, the North Korean navy finally opened fire on the fleeing American warship. Piracy? War? Dangerous lunacy? Whatever the official term, the matter had swiftly become fraught with peril.

It took no more than one frantic hour for it all to play out. Topside, the crew did their best to avoid or to mitigate the withering bursts of gunfire—but shrapnel was flying everywhere; fires were breaking out; glass was shattering and the shards flying; bullet and shell holes were being punched into the hull, the smokestack, the bulkheads. Men were injured—one young man, a fireman named Hodges, was hit in the abdomen and leg and died from an immense loss of blood.

Belowdecks the wreckage was even worse, though of the crew’s making, since standing orders demanded that everything classified now be reduced to garbage, useless and unreadable by any captors. So technicians with axes and sledgehammers hacked away at the electronics—finding them remarkably robust, resistant even to the cruelest of blows by the strongest of men. There were tons of papers to burn or shred, and only a small incinerator and a one-piece-at-a-time shredder with which to do the job. So, below, scores of small fires were set, the smoke filling the classified radio room and forcing its ax-wielding technicians to leave, choking, in search of fresh air—only to be forced back into the inferno as yet more shellfire erupted from the shadowing Korean boat.

The radio operator opened a link with the navy operations room in Japan, and the whole sorry progress of the one-sided firefight was then broadcast to a team of presumably open-mouthed operators back in the safety of headquarters. Bucher was at first still trying to get away, still heading east, but his full speed was a lame and limping thirteen knots, which the enemy vessel, now alongside, could easily match. More shells were lobbed at the Pueblo, prompting the single mutinous moment of the incident: the ship’s chief engineer, viewing the situation as hopeless, demanded that the vessel come to a stop and, seeing Bucher’s momentary indecision, wrenched the pilothouse annunciator to stop all engines, which the engine room unquestioningly obeyed. The American ship decelerated quickly and sighed to a stop, finally bobbing sulkily on the half-calm swells. Black smoke billowed from every porthole and every ventilation shaft as more and more paper fires were set, the frantic continuance of a vain attempt to destroy everything.

Then the gunfire stopped, and there was sudden silence—just the slap of cold waves against the hulls of the near-touching boats. No one aboard the Korean vessel knew enough English to shout orders, so the Koreans raised yet another string of flags, with new orders. “Follow me—I have a pilot aboard.” Bucher ignored them. The sailors then angrily pointed up at the flapping strings of colors, internationally recognized and requiring no language skills, demanding the American ship turn around and do as bidden. AK-47s were raised to shoulder height. The foredeck cannon was trained and leveled. Korean sailors, unsmiling, put fingers to triggers, awaited orders to annihilate the Americans, so close, so vulnerable, so theirs.

Bucher could do little more than breach the cardinal rule of all naval officers worldwide: never give up your ship without a fight. James Lawrence’s battle cry, his dying command “Don’t give up the ship,” is a mantra of consummate importance to every American sailor. But Bucher would do the opposite: he would make the entirely contrary decision, and one that would haunt him for years to come. For not only was he unable to destroy all classified documents and machinery (to the eternal chagrin of the intelligence community), but also he simply acquiesced when asked to turn over his ship to an enemy. He did what he was told and didn’t fire a single shot in defiance.

Commentators in America would long be unforgiving: one could hardly imagine, they said, that John Paul Jones or Admiral Farragut or even Lord Nelson or Rodney would ever have done such a thing. They would have traded shot for shot, lead for lead, crewman for crewman, and they would have gone down if necessary with a crippled and burning ship, her ensign sinking into the depths just as the captain’s hat floated off to join it. That was the way navies did things. To do otherwise was unworthy, unacceptable, un-American.

But Lloyd Bucher did it anyway. This forty-one-year-old rakehell from the arid plains of southern Idaho, a man brought up as an orphan in the Nebraskan prairies, who went to college on a football scholarship, and who could in no sense ever be said to have had seawater in his veins, promptly acted in the western Pacific Ocean as no true-blue sailor would ever have done, they said. He ordered his helmsman to turn about and to limp slowly toward land, to slide westward (at a paltry four knots, to enable yet more papers to be added to the pyre). He sailed his sad little ship morosely toward the enemy shore, to acquiescence, and to be henceforward inevitably thought of in connection with such words as surrender, captivity, humiliation, and shame.

“Now hear this!” the Pueblo’s public-address system barked. “Now hear this! All hands are reminded of our Code of Conduct. Say nothing to the enemy besides your name, rank, and serial number!” Then, within seconds, there was the stamp of heavy-soled boots on the iron deck, and ten North Korean soldiers with automatic rifles and fixed bayonets boarded the American vessel. Pueblo’s maiden voyage as a spy ship was officially over, little more than two weeks after it had begun. She was under arrest, and so were her captain and all her crew.

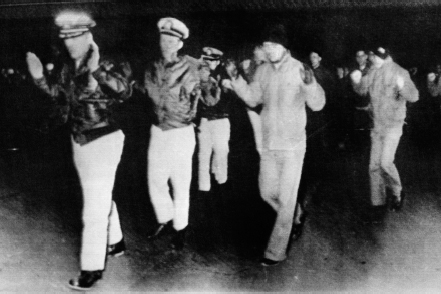

The ensuing fate of the men and their ship is recorded either in the memories of eleven months of beatings, interrogations, starvation, and humiliations or else in the black-and-white photographic images taken by their captors. First there were Captain Bucher and his men, the officers in black leather jackets and with naval caps displaying their official insignia, the enlisted men in fatigues and woolen beanies, walking in single file through the night with their hands held high, abject, defeated, captive. Next there is a group of sailors seated in a prison cell, potted plants placed to suggest home comfort;* some of the Americans have their middle fingers extended, in what they later explained to the North Koreans was a Hawaiian good luck sign. (When the North Koreans found out from a tactless caption in Time magazine what the gesture actually signified, the responsible men were beaten.) There are images of one sailor, Stephen Woelk, in a reenactment of a surgery performed on him without anesthetic, and then of him smiling at having survived the surgery. His own recollections are somewhat more vivid:

The Pueblo’s eighty-two surviving crewmen, led by Captain Lloyd Bucher, were held in prison in North Korea for eleven months, before being freed at Christmas 1968. They were greeted at the DMZ by the then general Charles Bonesteel.

Associated Press.

I believe it was the evening of our tenth day of captivity, I was removed from our room and taken to what appeared to be a medical examining room, just down the hall. Up until then, no major medical help had been provided to any of us. In this examining room, I was placed on a metal examining table, my hands were bound and tied down to the table. My legs were spread, my feet bound and tied down so I was unable to move. Their so-called NK doctors commenced operating on me without any form of anesthetic whatsoever. I can still recall the scissors cutting away flesh and being sewn up with sutures that looked like kite string. A small handful of shrapnel was removed in the operation that seemed to last an eternity, but probably did not last more than twenty to thirty minutes. I was told later my screams could be heard throughout the building and many crewmembers thought one of us was being tortured. I was then returned to my room and fellow wounded crewmen.

Aside from the crewman killed in the initial raid—Duane Hodges, a firefighter colleague of Mr. Woelk, whose own injuries were sustained in the same attack—all the Pueblo crew members survived their months in prison. And Mr. Woelk, despite the exiguous medical care, recovered:

My medical treatment would consist of the doctor taking a pair of forceps and shoving long strips of gauze saturated with a type of ointment down into my open wounds as far as it would go. Each day the healing process would not allow him to shove it in quite as far as the last time. One day something came out with the gauze that drew the attention of the doctor and his staff. It appeared that a bed bug had found refuge and a warm place to sleep inside of me. This did not seem to be a big deal to the staff. This was probably a normal occurrence in the everyday life in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. I also received several injections daily and one transfusion of a clear liquid in my leg. Although my leg swelled to twice its normal size, whatever medicine it was seemed to work since I finally started making headway towards a recovery.

All the men, fit or injured, officers or enlisted men, had similar tales to tell, of brutality, isolation, hunger, sadism. They knew little of the negotiations going on between Washington and Pyongyang to allow their release, or of the utter unblinking intransigence of their captors and those who represented North Korea at the bargaining table. It took the better part of a year for a deal to be brokered.

The Pueblo talks were conducted across a plain baize-covered table at the DMZ crossing point of Panmunjom—the site, still notorious and much visited by tourists, is where the original armistice talks were held that brought the Korean War’s fighting to an end fifteen years before. Like most negotiations with the North Koreans, these talks had the affect of a parallel universe, a strange dystopian Alice in Wonderland world where little was as it seemed, where there was much shouting, spluttering, and fist waving, and where truth was more fugitive than in other, more rationally organized places. The opening of the discussions—officially the 261st meeting of the UN Command Military Armistice Commission, to which the Pueblo incident had been formally added—began with a statement by the North’s granite-faced and unsmiling chief negotiator, Major General Pak Chung Kuk. His opening remarks to the lone American negotiator more than amply set the tone:

Our saying goes, “A mad dog barks at the moon.” I cannot but pity you who are compelled to behave like a hooligan, disregarding even your age and honor to accomplish the crazy intentions of the war maniac [President Lyndon] Johnson for the sake of bread and dollars to keep your life. In order to sustain your life, you probably served Kennedy who is already sent to hell. If you want to escape from the same fate of Kennedy, who is now a putrid corpse, don’t indulge yourself desperately in invectives. . . . Around 1215 hours on January 23 your side committed the crude, aggressive act of illegally infiltrating the armed spy ship Pueblo of the US imperialist aggressor navy equipped with various weapons and all kinds of equipment for espionage into the coastal waters of our side. Our naval vessels returned the fire of the piratical group. . . . At the two hundred and sixtieth meeting of this commission held four days ago, I again registered a strong protest with your side against having infiltrated into our coastal waters a number of armed spy boats . . . and demanded you immediately stop such criminal acts . . . this most overt act of the US imperialist aggressor forces was designed to aggravate tension in Korea and precipitate another war of aggression. . . . The United States must admit that Pueblo had entered North Korean waters, must apologize for this intrusion, must assure the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea that it would never happen again.

In the end, the Americans did as they were told. Or they went through the motions of doing so. They agreed, in essence, to the three A’s (to making an admission, giving an apology, pledging an assurance), only to repudiate all three within moments of signing the document. This tactic, this form of words, the use of bizarre new terms for what would happen—prerepudiation, a word absent from most dictionaries, was one; the term prior refutation another—was fully accepted beforehand by the Communists. And this merely added to the perception of these talks, as with most of the Panmunjom talks to have taken place in the sixty years since the end of the war, as being part of a witch’s brew of near insanity, with many of the sessions unreal and frightening by turn.

The result of these negotiations was the eventual freedom of the eighty-two men and the return of the body of the hapless Duane Hodges. As President Johnson had wished, the men were released in time for Christmas 1968. They were brought in buses to the Joint Security Area (JSA), that small bubble of hope and horror that straddles the dividing line between the two Koreas. The MDL, the military demarcation line, runs through the bubble, with buildings of North Korea on one side, of South Korea on the other, and a few heavily guarded structures built across the line itself, and is where such talks as take place do so across tables that have the line passing through their exact midpoint.

There is a shallow and muddy river, the Sachon, that dribbles through the western half of the JSA bubble. The demarcation line runs through the midpoint of the river, so any bridge crossing it would, ipso facto, cross the MDL as well. There is in fact such a bridge, an unattractive concrete affair two hundred fifty feet long, with a North Korean guardhouse at the western end, a guardhouse manned by American troops at the other. It has long been known as the Bridge of No Return, since Korean War prisoners who elected to cross it for postwar repatriation were told that, once across, they could never come back. Captain Bucher and his men were brought to the western end of the structure on the chill morning of Tuesday, December 23. It was nine o’clock. They had had turnips for breakfast. It was snowing lightly.

In another building nearby, the negotiators were signing their sheaves of meaningless documents. It had been agreed that two hours after the final signatures, the men would be freed—but then, at the last minute, the North Koreans decided on another tiny torture, delaying matters by a further, quite pointless thirty minutes. Since the prisoners in their buses had no idea what was going on, they were unaffected. But for the negotiators and the political leaders back in Seoul and Washington, it must have been agonizing.

Finally word came down the telephone line from Pyongyang that all had been approved. Captain Bucher was ordered to step out of the lead bus and ready himself. He was first taken to a waiting ambulance, there to identify in an open coffin the mummified body of fireman Hodges, now eleven months dead. Then Bucher stood, bewildered, in the gathering snow, listening patiently as Major General Pak, the chisel-jawed man who had made the speech starting the negotiations six months beforehand, harangued him for twenty minutes about the evils of his life.

Then one of the better known and least liked of the guards who had presided over the prisoners, a man of studied cruelty whom the prisoners had called Odd Job, pointed Bucher toward the bridge entrance and spoke to him one last time: “Now walk across that bridge, Captain. Not stop. Not look back. Not make any bad move. Just walk across sincerely. Go now.”

The red-and-white-striped pole across the entrance was then raised. Bucher stepped onto the bridge and walked nervously, but steadily, across the ten cement arches that supported it above the ice-choked stream. At the far end was a delegation of friendly looking men with, as he came ever closer, ever-broadening smiles on their faces. They were Americans.

When he was just feet from safety, one of them took the final picture. It is black and white, of a now much older and much thinner Lloyd Bucher, in the last moments of his coming home. His mouth is set in a rictus, a faint and sardonic smile of exhausted relief. His left hand clutches the Mao cap he had been given, but had opted not to wear. His dark raincoat is tightly belted, its collar raised against the biting wind. His trousers are too short—flood pants, Americans would call them. His shoes are dark with white laces.

Behind him idles the ambulance bearing the body of Hodges. Back on the far side of the creek are the milling men of his ship, to be sent off on their way to freedom, one by one, by their guards, to follow their captain, to keep a strict twenty paces apart from each other. They had been ordered to walk, not run. They had been told not to dare look back at their captors. They had been told they were forbidden, on pain of being shot, to give the final one-fingered gesture of “Hawaiian greeting” so many had so dearly wanted to give.

Seen from above, from one of the American sentry towers, the handover was like watching sand move through an hourglass. On the far side was the dark crowd of the American captives, a mass that was steadily winnowing itself smaller and smaller as a line of dark-clad men poured slowly down through the narrow neck of the bridge and was then re-formed into an ever-enlarging crowd of men on the other side. The two groups may have looked just the same, like the sand in the glass. But the second of the two groups, even though at one halfway moment identical in size, was all of a sudden different from the first group, in that those in it were entirely free, and at last.

American sentries were watching all this from their towers. On the ground on the far side, also gazing impassively at the unfolding drama, were a score or more of green-fatigued men of the Korean People’s Army. They were presiding over a repatriation that was no more dignified than it should have been, and from which no one had drawn much of a victory, or a triumph, or a propaganda score. As the last American limped offstage, the Koreans turned away and got back on the buses to their barracks, to kimchi and cheap shochu and endless propaganda. The Americans went for steaks and showers, orange juice and telephone calls, and flights home, to meetings with wives and girlfriends and the usual celebrations and parades and oompahs that greet returning astronauts and Olympians and such other temporary heroes and survivors that Americans have come to admire and revere so much. In time there would be courts of inquiry and investigations and postmortems, and then memoirs and interviews and reminiscences. But not today: ahead was Christmas, and freedom.

There was one final irony for the men, though it passed unrecognized at the time.

As they stepped off the concrete abutments of the bridge and into a hut decorated with Christmas tinsel and lights, they were each to be greeted in person by the commander in chief of the United Nations Command, the senior Allied soldier sent in to protect South Korea. The C-in-C at the time of this event was none other than U.S. Army general Charles Hartwell Bonesteel III, the same man who, as a mere colonel almost a quarter century before, had so casually defaced a National Geographic map on a Pentagon wall, and whose innocent remark that “the Thirty-Eighth Parallel should do it,” led to the creation of North Korea in the first place.

Had Bonesteel not drawn his grease pencil line late that summer’s night in 1945, the melancholy chain of events surrounding the capture of the USS Pueblo probably would never have taken place.

The seizure of the Pueblo* may have been one of the most painful episodes in America’s entanglement with North Korea, but it was not to be the last. More than sixty years have elapsed since the signing of the armistice, and almost every year has been peppered with events that have been, by turns, lethal, curious, frightening, or all three. Even a cursory summary of the more serious happenings confirms the idea that North Korea has been an interminable nuisance. In 1958 an airliner on an internal flight in South Korea was hijacked and flown to Pyongyang. In 1965 two MiG fighters attacked an American plane fifty miles off the coast. In 1969 four American soldiers were ambushed and killed on the southern boundary of the DMZ. In February 1974, North Korean patrol boats sank two South Korean trawlers. In August 1974, South Korean president Park Chung Hee’s wife was shot dead by a North Korean agent in Seoul. In 1978 a South Korean actress and her film director husband were kidnapped in Hong Kong and smuggled to Pyongyang. In 1983 three South Korean government ministers and fourteen staff were among twenty-one people killed in Rangoon by bombs smuggled through the DPRK embassy in Burma by North Korean agents.

One of the more notorious events took place inside the Joint Security Area, on August 18, 1976, when a group of American soldiers attempted to trim a poplar tree close to the end of the Bridge of No Return because it obscured their view of the North Korean watchtower at the far side, the same one from which Captain Bucher began his lonely walk to freedom. North Korean soldiers protested, absurdly, that the tree had been planted by their Great Leader, Kim Il Sung, and so should be considered inviolable. When the Americans continued to prune its branches, a posse of North Korean soldiers rushed them with axes and crowbars and bludgeoned and hacked two American officers to death. Four other Americans and five South Korean soldiers were also badly injured.

Washington, it turned out, had been pushed just a little too far. Three days later the so-called ax murder incident at Panmunjom triggered an almost unimaginable American response. It was called Operation Paul Bunyan, and it had the full approval of an enraged President Gerald Ford. Its mission, undertaken in the spirit of the legendary lumberjack, was to cut down the entire tree. On the face of it laughably trivial, a simple enough exercise, a robust response, a small opportunity to redress the sad capitulation of the Pueblo.

Except it was very much more than this. The deliberate American plan was to use this single small arboreal incident to demonstrate to the North Koreans that, as Washington liked to put it, “you don’t mess around with Uncle Sam.” The White House let it be known that the disproportionately immense team assembled to cut down the tree—with twenty-three vehicles, two engineering companies, sixty American security men, a sixty-four-man South Korean special forces team, and a howitzer big enough to blow the Bridge of No Return to smithereens—was to be supported by as much power as the Americans needed in the event any North Koreans dared to retaliate. “Take that, President Kim,” the Americans seemed to be saying.

So a backup assemblage of armor and weaponry was put together on a scale seldom seen in peacetime, and only occasionally seen in war. Lurking just outside the DMZ, ready to move at an instant’s notice, was an entire U.S. infantry company and nearly thirty helicopters to ferry them into battle. B-52 bombers had been scrambled from Guam, F-4 Phantom jets were swooping in from bases all around the region, F-111 fighters had come in from their faraway base in Idaho. There were Hawk missiles at the ready, the carrier group of the USS Midway had been moved close to the coast, nuclear-capable bombers were flying overhead, and twelve thousand additional troops and eighteen hundred U.S. Marines had been put on standby to fly to Korea.

In the end, the tree-cutting party took just forty-three peaceful minutes to bring the poplar down and to trim its remains to serve as a memorial to the officers who had died three days before. By the end of that hot summer day, the forces had been stood down, the bombers sent back to routine patrolling, the fighters sent back to their revetments in Japan and the Philippines and faraway Idaho. America, for once, felt it had managed to shock and awe the North Koreans into some semblance of common sense and good order.

Yet it would not last. The regime constructed by North Korea’s doctrinaire soldier founder, Kim Il Sung, evolved into a dynasty of unparalleled and ever-increasing cruelty and hostility, behaving toward its own people and the world in ways quite detached from the norms of even the most bizarre. Perhaps only Pol Pot’s Cambodia can offer a valid comparison. Or maybe Albania, during the most extreme excesses of Enver Hoxha’s time. Or perhaps Idi Amin’s Uganda, at its worst.

The original national philosophy of juche, a form of self-reliance coupled with extreme nationalism, and which, according to state propaganda, was dreamed up by Kim Il Sung at an improbably early age (ten years old, according to some), steadily transmuted itself, as Kim’s son and then his grandson took over the reins of governance. There was a time when some felt that Korean self-reliance was not a bad thing—after all, India, with its own rigid application of a similar idea, swadeshi, which forbade the importing of virtually anything from outside, worked well for a time. Moreover, the early ideas of Kim Il Sung allowed this half of Korea to retain some sense of a uniquely Korean identity, even as it was being demonstrably lost in the very Westernized and commercialized atmosphere of South Korea.

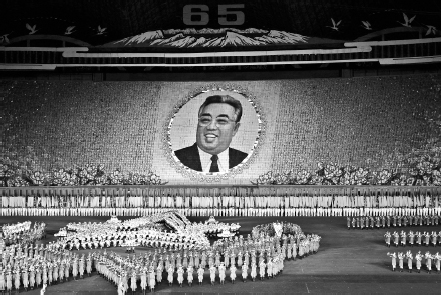

Hypnotic organized performances by thousands of impeccably drilled youngsters—known as “mass games,” with any misstep harshly punished—are one of the few signature achievements of North Korea.

Roman Harak.

But juche went slowly insane. Lenin, Marx, Engels, and Trotsky, in common with such Communist sponsors who still pay lip service to the old Soviet regime, would be hard-pressed to recognize the autarkic impoverishment that guides North Korea today. In the republic’s earliest days, it might have enjoyed some kind of reputation as a failing form of socialism, an experiment that didn’t quite work, but that had a kind of nobility of purpose. Instead, the country has evolved into a snarling, spitting, and ceaselessly hostile monster of a nation, an alien life-form that lurks menacingly in the folds of the East.

There is widespread hunger, grinding poverty of a depth and kind unknown elsewhere in the world for decades past. There is almost no personal freedom, and punishment for the slightest of crimes against the state or the dignity of the guiding ideas or their practitioners is swift and pitiless. One senior soldier was executed for seeming to nod off during a cabinet meeting—pounded into oblivion by antiaircraft cannon, some reports said. Another, reported by the lurid South Korean press to have been torn to shreds inside a cage of wild dogs, was the leader’s uncle—the fact of his kinship bringing him no mercy. Gigantic prison camps are scattered everywhere across the bleak and famine-racked landscape, and inmates are corralled within them in conditions unimaginable by even the darkest, most Orwellian, most Kafkaesque minds. One arrest can lead to the instant imprisonment of three generations of a family, the deliberate extinguishing of any potential for dissent by the preventive detention of the innocent.

I can never forget a visit I made to North Korea in the mid-1990s. If one consequence of my venture was dreadful, it was all my fault. One afternoon I was driven down to see the Panmunjom truce village from the northern side. I had a government minder with me, as always. He was a friendly man who spoke with carefully calibrated candor about the pleasures of living in the North, but liked also to voice at length his fantastic vision of the decadence and corruption of the South.

Our driver on that afternoon spoke not a word of English and smoked incessantly. He listened to his car radio, which like all Korean receivers had had its tuner welded to pick up just a single government station, one that pumped out a torrent of loud political exhortations, or else saccharine musical numbers of great patriotism and fervor. So when the minder stepped away from the car for a moment, I made what I thought was a kind gesture: I showed the driver the tiny Sony transistor radio I had in my pocket, and tuned it for him to pick up an American forces radio station. We were less than a mile from the border, and the transmitter aerials were visible.

It was a revelation. He had never heard anything like it. For the next ten minutes or so the snatches of music, and the announcer’s voice, seemed to give the driver the greatest pleasure, and he drummed his fingers on the dashboard, beamed broadly, and offered me cigarettes. His personality had completely changed. He seemed genuinely happy. Then, without warning, the door was wrenched open and the minder got into the car while my radio was still switched on. He barked angry questions at the driver, who had stopped smiling and who returned answers monosyllabically, sheepishly. The minder glowered as we were driven back to Pyongyang that evening in total silence. I never saw the driver again. No one later claimed to have any idea of his fate. In fact, in spite of much questioning, no one claimed even to know of his existence.

The savagery of this most ruthless police state is all but undeniable.* Within the country, though, there is a continuing and skillful attempt to mitigate its horrors by the endless presentation of the Kim family’s geniality and benevolence. The Kims are everywhere. The regime’s three founders, the Supreme Leaders, the eternal bestowers of guidance, have become so godlike that their given names, Il Sung, Jong Il, and Jong Un, have been banned from use by any other Koreans, and those already using the names have been ordered to change them. Photographs of the three men must now hang in every dwelling, there are immense marble statues of them in public places, and members of the Korean Workers’ Party must wear tiny brooches sporting the leaders’ enameled faces.

North Korea counts its calendar years from the date of Kim Il Sung’s birth, in April 1912, which was Juche Year 1. The year 2016 is Juche 104. On the Great Leader’s birthday each spring there are wild demonstrations of impeccably choreographed ecstasy, the so-called mass games, involving thousands of identically drilled children. The games are designed to have a hypnotic effect on a public glued to the state-controlled television. Similar demonstrations occur on dozens of other state holidays and anniversaries; and on more momentous occasions, the armed forces take part, with goose-stepping infantrymen and five-mile-long parades of missiles, tanks, and armored cars—all of them turning a show that is merely chilling into something truly alarming.

The North Korean army is immense—at almost a million soldiers, it is probably the biggest or (after China) the second biggest in the world. The country’s 2009 constitution gave the army primacy over all other institutions of state; the new notion of songun, as the army’s unchallengeable authority is now called, has ever since stood alongside juche as the state’s guiding philosophy. At the same time, the term communism, which in comparison seems almost quaint and harmless, was quietly dropped from the description of the DPRK’s central ideological principle.

That North Korea, already a fanatically militarized state, is by now formally ranking its enormous army as the leading instrument of policy worries everyone—this is a matter of ever-growing concern. The country’s attainment of a small number of crude but working nuclear weapons, along with sufficient rocketry to propel these weapons beyond its coasts, combined with its declared intention to punish anyone who has ever disrespected its leadership or its aims, presents a threat of real danger. In global terms, it may still be only a nuisance, but it is a serious, grave, and potentially bloody nuisance, which none in the outside world seems to have the power or ability to check.

The Korean DMZ, the central focus of all these nightmares, is a strange and dangerous place for humans. It is a place of searchlights and fortifications, watchtowers and minefields, howitzers and tanks, and the massing on both sides of countless stone-faced soldiers, heavily armed and ready to deploy at an instant’s notice. It is a place of strange and dangerous happenings—of shootings and stabbings, of the floating of balloons containing propaganda or poison, of the building of giant illuminations (usually of Christian crosses) that are designed to advertise god to the godless. Loudspeakers of incalculable decibellage blare the sayings of one or another of the Kims to listeners in the South.

Once, when I had completed a three-month walk up the entire length of South Korea and had arrived at the end of the Bridge of No Return, the loudspeakers were screeching out in English, welcoming me, inviting me to walk farther, to cross the bridge and savor the delights of the Democratic People’s Republic. It seemed a fine idea, but the U.S. Marines who had escorted me through the Joint Security Area were having none of it. Could I just walk across the bridge? I asked. Definitely not, they replied, and added “sir,” for emphasis. And what if I just set off and walked? They drew themselves up to their full, imposing height. We’d break your fucking legs, they said. Again, they added “sir,” for emphasis.

But there is more to the DMZ than mere menace. Though it may be a strange and hostile place for humans, it is, for example, anything but for flotillas of Siberian cranes and hordes of brown bears, musk deer, and the goatlike Amur gorals, who flourish in what is for them a sanctuary, a gun-free, human-free four-kilometer-wide swath between the two great fences. The creatures can hardly be petted, or visited, or even accurately counted. But they are there, munching and fluttering and preening under the gun sights of thousands, oblivious to all the anger and ideology swirling around them.

And there are some moments in and around the DMZ that have a certain charm to them. One such took place for me late in the 1990s, when an American magazine of some flamboyance wondered if it might be possible to stage a lunch party in Korea—“somewhere interesting” as the publisher put it, “like the middle of the Korean DMZ.”

It seemed at first a quite ludicrously impossible idea. Only wild animals (the aforesaid cranes, bears, and gorals) inhabited the DMZ—or so I thought. On a trip to Seoul to investigate other potential sites—the abbot of one of the loveliest Buddhist monasteries in the world, Haeinsa, said he might know of a nearby hall we could possibly use—I mentioned to a diplomat friend the impossibility of lunching in the DMZ. “Not so fast,” he said. “Have you tried the Swiss?”

I had quite forgotten about the Swiss. At the time of the signing of the 1953 armistice, a group of four supposedly neutral countries agreed to monitor the cease-fire. The North had nominated as its two countries Poland and Czechoslovakia; the South had selected Sweden and Switzerland. I telephoned the Swiss embassy for details, and was given the number of the only major general in the Swiss army, a civilian diplomat deputed for five years at a time to take charge of his Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission camp, up by the JSA at Panmunjom. He was delighted to have someone stop by; he saw few outsiders. “Just American soldiers,” he said. “You know how that can be.”

His camp was in a small spinney right inside the DMZ and just outside the JSA. To get there, I had to drive to the American base camp outside the DMZ and wait for a Swiss guard to come collect me, which he did in a white-painted Mercedes G-wagon. He took me through well-guarded double gates in the fences, along a gravel driveway, and up to a comfortable little headquarters house, a cottage with a mess room and bedrooms for the ten or so Swiss soldiers who had been sent out from Bern to help keep the local peace.

The general was an affable middle-aged officer, clearly weary of his tour between the Koreas, and now readying himself to leave and take up a job as Swiss consul general in San Francisco. He was up for anything, he said; yes, he had a chef, who was, in truth, rather bored cooking for Swiss soldiers; and no, he hadn’t given a party up on the DMZ for many months past. But he’d very much like to.

It would be a great relief for him, considering what he called the “comical absurdity” of his situation. Absurd mainly because of what had happened since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, and the abandonment of communism by the North’s two chosen neutral nations, Poland and Czechoslovakia (and the division of the latter into two brand-new and entirely capitalist countries). North Korea had responded to the apostates by kicking their observers out of the country, leaving only the Swiss and the Swedes to maintain the monitoring. Except that the Poles kept on trying to send at least one delegate to maintain the fiction that the commission still existed, or three-quarters of it anyway. North Korea, which has made denunciation into a cottage industry, still denounces this near-beer body as something “forgotten in history” that is now no more than “a servant of America.”

Nonetheless, each Tuesday the countries’ representatives meet in formal session—about thirty-five hundred meetings have taken place since the cease-fire in 1953—and discuss and take notes of all the various alleged breaches of the cease-fire and other such matters (tunnel diggings heard, snips in the barbed wire noticed), and write a report. They place these written reports in a mailbox marked KPA, for Korean People’s Army. But since 1995 no North Korean has ever picked up the mail, and so every six months an official from the commission empties the overflowing mailbox and puts all the reports into a file cabinet, just in case Pyongyang ever demands to see them.

As it happens, the door of the commission’s hut opens directly into North Korean territory, and for a while the Swiss general would unlock it and wave the latest report at the soldiers a few yards away. They turned their backs and ignored him, never came to collect the document, and later complained that the waving constituted an offensive gesture. So with a sigh of frustration the general stopped opening the door, not wanting to provoke or seem impolite, and maybe see for his pains the business end of a Korean-made AK-47.

So, yes, he’d very much like to entertain our party. How many guests?

A date was set, and at an appointed hour, forty distinguished men and women from the advertising world—the magazine I was writing for was eager to impress and show gratitude to those who placed advertisements on its pages each month—duly arrived at a U.S. Army base in central Seoul. They were told what to expect, told how to behave—no pointing at North Korean soldiers, no sudden movements, no loud remarks—and were kitted out with flak jackets and steel helmets “just in case.” They were then herded onto two large Chinook helicopters, which rose and then chugged for a half hour up over the mountains and paddy fields north of the city to a river and a ruined bridge, and then settled down on a grassy sports fields at the American forward operating base. A long line of Swiss vehicles was waiting for them, the general in the lead car with pennants, insignia, and the paraphernalia thought likely to appeal to his visitors. The entourage set off through the great fence gates and up to the peaceful-looking wooded grove set down in the very middle of it all.

For the next three hours we sat at a dining table eating rösti and raclette and chocolate fondue. Out one set of windows we could glimpse in the distance American soldiers drilling, cleaning their weapons, changing duties, jogging. Through the other windows, those looking out over the cold mountain to the north, we could see North Korean artillery pieces and armored vehicles and the barracks of scores of soldiers performing precisely the same tasks as the Americans, from whom they were separated by two mighty fences and two enormous minefields and four kilometers of grassland, with their populations of wild deer and bears and goatlike Amur gorals.

What we all remembered most, I suspect, was the constant querulous voice on the North Korean loudspeakers, repeating in a soaring monotone the words and wisdom of Kim Il Sung, who had chosen first to rule this benighted country and whose generations of offspring have ruled it, dangerously and wickedly, ever since.

Charles Hartwell Bonesteel III, who back in the summer of 1945 first drew the pencil line that marks the true epicenter of all this, the line that ran down the center of the Swiss general’s Panmunjom dining table, came to know something of the DMZ’s dangers when he welcomed Captain Bucher and the Pueblo’s crew back across the Bridge of No Return in 1968. This third-generation military man, educated at West Point and Oxford, is now long dead, interred at Arlington National Cemetery. He would without doubt be astonished to see how North Korea has endured, and has so case-hardened and strengthened itself in the years since. Quite unwittingly, the good colonel left the world a powerful legacy—one that to this day, seven decades on, remains memorable, malevolent, unpredictable, dangerous, and a terrible, terrible nuisance.