January 12, 1970: The Boeing 747 takes its maiden flight.

June 4, 1970: Tonga becomes independent from the United Kingdom.

December 31, 1970: Allende nationalizes Chile’s coal mines.

JANUARY 10, 1972: THE RMS QUEEN ELIZABETH SINKS, HONG KONG.

February 21, 1972: President Nixon visits Mao’s China.

January 27, 1973: The Vietnam Peace Accord is signed.

April 4, 1975: Microsoft is founded, Seattle.

The enemy has overrun us. We are blowing up everything. Vive la France!

—FRENCH RADIO OPERATOR’S FINAL WORDS, MAY 7, 1954, BATTLE OF DIEN BIEN PHU, INDOCHINA

I have relinquished the administration of this government. God Save the Queen.

—HONG KONG GOVERNOR CHRIS PATTEN, FINAL TELEGRAM TO LONDON, MIDNIGHT, JUNE 30, 1997

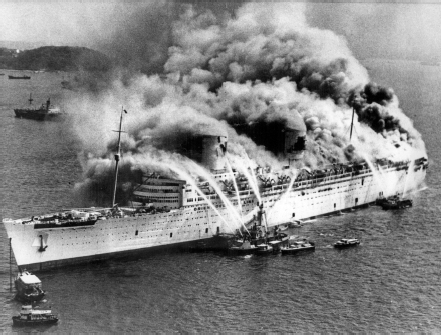

She was the loveliest ocean liner the world had ever seen—eighty-three thousand tons of Clyde-built elegance and pride and craftsmanship, a ship of longing and allure and fine cuisine, of passions promised over her moonlit taffrail, of romances hatched in the sway of her grand saloons. But just after noon on a winter’s Monday in Hong Kong, half the world away from her Scottish birthplace, the burning and twisted wreck of this mighty vessel capsized onto her starboard side and slumped down heavily into the shallow, greasy waters of the harbor, never to rise again. The Royal Mail ship Queen Elizabeth, the younger of the pair of great and graceful sister ships that had for decades dominated the grand luxe transatlantic run, had come to her most wretched and unseemly end.

Unseemly endings are everywhere in this part of the modern Pacific’s story. So far as the great old ship is concerned, the British firm that built her, John Brown of Clydebank, vanished in financial ignominy. In 1986 the British firm that operated her, Cunard, was reduced to a mere subsidiary of another giant, and now it possesses only three ships, compared with its fleet of sixteen back when the Queens were sailing. And Hong Kong, the British colony where the liner sank, was wrested from London’s hands in 1997 and is now an increasingly Chinese part of China.

Endings of varying degrees of seemliness extend through the Pacific far beyond the waters of Hong Kong Harbor. Since the sixteenth century and the first crossings of the ocean by exploring outsiders, it has provided foreigners (Europeans, mainly) with an immense imperial playground, with territories for all sides to take, either for wholesale exploitation or for the simple amassment of regional power. The Portuguese came first; and then, in quick succession, the Pacific’s great coastal states and its long drifts of islands were snatched up by the Dutch, the Spanish, the British, the Russians, the Germans, the French, the Japanese, the Americans, the New Zealanders, and even the Norwegians, all in three centuries of uncontrolled imperial greed.

Yet so many glorious beginnings were inevitably followed by as many inglorious endings—with the result that all these various powers have retreated from the ocean, leaving the Pacific now almost entirely to its own devices, to be run by its own people.

The graceful Cunarder RMS Queen Elizabeth, shown in her glamorous heyday and at her sad sabotaged demise in Hong Kong, had a thirty-three-year life, which marked the beginning of the decline and fall of the British Empire.

Associated Press.

Louis Gardella.

The foreigners’ first withdrawals from the ocean began, effectively, in the mid-1950s, when France came to accept the reality that its once great Southeast Asian peninsular landholding “Indochine” was no more, and had to be returned. For the next forty years, farewell ceremonies seemed to be held almost monthly, with alien flags lowered and swansdown plumes, helmets, and swords being loaded into cabin trunks and sent home to London, Lisbon, Paris, The Hague, and Washington, from islands and outposts dotted in and around the gigantic blue space of sea. Hong Kong was the last of the outsiders’ grand territories to be handed back—it was retroceded—and this was done with appropriately grand ceremony, half a century after the French pulled down their tricolor in Hanoi.

The sinking of the Queen Elizabeth, which took place twenty-five years earlier, more or less halfway between the return of Hanoi and that of Hong Kong, might well serve as a symbol for the frailty of empire. It was a reminder of the temporary nature, the sinkability, of all the foreign majesty wielded in this great expanse of sea. That the sinking occurred to a Western-made sea machine, and under circumstances that were peculiarly and bewilderingly Pacific in their nature, helped make the symbolism of the event all the more potent.

The Cunard Line had first sold off its two Queen liners in 1967. The great ships had operated across the North Atlantic ever since the end of World War II, and both had at first been filled to the gunwales with more than two thousand paying passengers each week. But it was a creature of the Pacific that proved their nemesis: the made-in-Seattle four-engine passenger jetliner the Boeing 707.

Starting in the late 1950s, when three airlines began using these jets to run daily ferry service between London’s Heathrow Airport and Idlewild in New York City, all of a sudden crossing by ship seemed quaint and inefficient. Despite Cunard’s slogan suggesting that “getting there is half the fun,” the paying public decided that getting there and back in half the time was much more sensible. So, in their thousands, they abandoned the ships, leaving them embarrassingly empty, light in the water.

“Space is usually available on all departures,” read a dismayed internal note to Cunard directors in 1965. The combination of vacant staterooms and low-budget passengers steadily reduced Cunard’s profits to the thinness of the cucumbers in the Britannia lounge’s afternoon tea sandwiches. And though the firm added to the Queen Elizabeth a three-million-dollar outdoor swimming pool, a Lido Deck, and other touches that it thought holidaymakers might like, and then packed the liner off to try wintertime cruises in the Bahamas,* the figures continued to slide. In the end, the unsentimental clicking of the back office abacuses sounded the death knell. The Queen Mary was sold first, in August 1967, and on Halloween she sailed off by way of Cape Horn to the Pacific to be, as she remains today, a cemented-in-place hotel and museum on the Long Beach seafront, a successful and well-liked international seamark now remade as a successful and well-liked local landmark.

The Queen Elizabeth’s fate was to be very much more complicated, very much less dignified, and ultimately, a terribly sorry one. The moment that Cunard put the liner on the block, there came a buzz of intense interest—but a buzz that quickly faded. The firm heard about vaguely suitable offers from companies in Brazil and Japan, but these never materialized, and as many as a hundred others were haughtily dismissed. Eventually a group of American investors in Philadelphia made a real offer; their plan was to moor her in a swamp on the Delaware River and run her as a hotel, similar to the Mary on the far side of the country. But they never checked to see if she would fit in the river (she wouldn’t), or how customers would get to her (a brand-new highway would have to be built).

Yet, for inexplicable reasons, the Cunard chiefs stuck with these investors, and a deal was made for the liner to become a hotel not in a Chesapeake Bay swamp, but by a nicely tropical beach in Florida. After a series of formal farewells—one a banquet attended by the Queen Mother, the very Elizabeth who had launched the ship thirty years before—the Queen Elizabeth left Southampton at the end of November 1968 for what many hoped was some kind of dignified future.

It was not to be. She scraped into the port with inches to spare beneath her keel and promptly had the word Queen erased from her name with welding torches. Soon after, she was declared a fire hazard and then began decaying in the damp Florida heat. Meanwhile, among her buyers and their friends, people involved were shot, whacked Mafia style; others went to prison on racketeering charges; some declared bankruptcy; others appeared in long-drawn-out American court battles in which hapless and bewildered Cunard executives from London were brought across to testify.

When two of the original buyers were jailed, Cunard put the forlorn ship up for sale again—and in September 1970 a Shanghai-born shipowner, Tung Chao Yung, bid three million dollars for her at auction. He would take her to Hong Kong, he said, where he would restore her to her former glory, establish her as a floating center of learning and intellectual discourse, and rename her Seawise University. Eight hundred first-class passengers and eight hundred students would sail with her. “She will be more beautiful than ever,” Tung promised.

It first took almost one million dollars to make the ship safe enough to take to the seas, and even then the journey to Hong Kong was something of an ordeal. Her boilers broke down. She spent hours adrift, powerless, off Cuba. For days, there was no running water aboard, and welders had to affix three-seater toilets to the outside of the ship’s boat deck, where passengers could go to perform their natural functions, using gravity and the sea instead of the flush and the pipe. She then had to be towed to Aruba, where she spent three months having her engines repaired. She eventually arrived in Singapore, and Royal Air Force jets flew over to salute her as she was tugged to her berth. Two weeks later, in July 1971, she finally arrived in Hong Kong—though she arrived a day early, and had to sail back and forth, south of the colony, like an actress with stage fright waiting for her curtain call. It had taken her five expensive months to perform a journey that a cargo vessel would have done in six weeks. C. Y. Tung was twelve million dollars in the hole already.

Upon her entering British colonial waters, a fireboat performed a water storm of welcome—a prescient gesture, considering what would then unfold. For, as she anchored off Tsing Yi Island, and as her first refitting got under way (new paint, new cabins, new boilers), there came ominous warnings, particularly of that most feared enemy of all deep ocean ships: an outbreak of fire.

Ship fires are terrifically dangerous—with all that fuel aboard, with hundreds of tons of combustible materials, with scores of passengers and crew. They are also very hard to fight—foul weather and great distance can hinder any firefighting efforts from outside, and if water is pumped onto the blaze, it may well endanger the vessel’s buoyancy. After “the indiscriminate use of large quantities of water,” reads one of the standard manuals on the subject, “the ship may be lost as a result of instability, and not because of the fire.”

Hong Kong government officials had been openmouthed with dismay at the lack of fire precautions they discovered when they had toured the great ship. They found sprinklers out of order, an electrical system as frayed as the carpets, fire hoses not working, main pipes cracked and blocked, watertight doors left open, and no fire crews with any idea of how to fight a blaze. Twenty-one recommendations for improvements were swiftly made: if the Queen was left as she was, said the government, she “presents an extremely dangerous fire and life risk.” Mr. Tung said he would do all that was asked.

But his problem turned out to be political, a classic Pacific collision between ideological systems that were both Asian and American, even between races. For, many years before, Tung had committed what to some appeared a heresy: he had turned his back on Communist China. Like so many Hong Kongers of his generation, he had fled by way of Taiwan to the British colony, and there had run an empire of profit, indulgence, and entrepreneurialism. He had lived a life that was entirely counter to the attitudes and aspiration of the Communists and, more important, because of his unique situation, of the Communist agents who were operating among the working millions in Hong Kong.

For, in the early 1970s, the colony was an ideological tinderbox. In China the Cultural Revolution may have been starting to wane, but the Red Guards were still ferocious and active, and the turmoil that had convulsed the mainland since 1966 frequently seeped southward, into the British colony, and erupted in demonstrations and riots that had sorely tested the local police and militia.

Strikes and slowdowns were a constant threat, and though by the early 1970s the main sources of disruption had been largely tamped down, there were agitators and troublemakers aplenty still active. Many were active in the labor unions, and most especially of all, there were many among the workers who came each day to hammer and chip, weld and paint, on Mr. Tung’s great white whale of—as they liked to see her—a onetime British imperialist, white man’s ship.

Moreover, the ship now sported a new symbol sure to envenom the more radical of these workers. Tung’s company symbol was a plum blossom, and he demanded it be etched onto the old Queen’s two funnels. The flower was not the Tung logo alone; it was also a symbol of Taiwan, the island republic that had broken away from Communist China, and was particularly loathed and despised for having done so.

But if the workers on the ship felt they had cause to abominate their bosses, the Tung managers had their own reasons to be irritated with the workers. They grumbled, for instance, when the laborers left the ship each lunchtime to eat ashore, declining a bizarre offer by Tung’s managers to stage Cantonese operas in the liner’s ballroom in an effort to persuade them to stay. Many of the painters and cleaners demanded time to play poker and mah-jongg, ran onboard gambling rings, and demanded to smoke whenever and wherever they liked.

Moreover, it was also believed that many of the dockyard workers were members of the Triads, the Mafia-like secret societies that practiced big- and small-scale villainy in a colony that was riddled with corruption and whose police force did little to clamp down on the gangs’ activities. Anyone who objected to the workers’ right to smoke, gamble, or eat where they liked could easily be hacked to pieces with a meat cleaver, the weapon of choice, both now and back then, for the Triads’ pitiless hit men.

Yet despite all this poisonous stew, C. Y. Tung remained confident that things were going well and that his Seawise University project would work out in the end—that is, until people spotted smoke shortly after 11:00 a.m. on Sunday, January 9. Wintertime weather in Hong Kong is more often than not calm, clear, and, to most non-Asians, comfortably warm. That morning, barbecues were getting under way on a score of rooftops at the western end of Hong Kong Island and up on the mid-levels of Victoria Peak. As the first gin and tonics were poured, those gathered together couldn’t help focusing on the great newly painted white liner gleaming brightly in the southern sunshine.

Then, at once, they began to notice that all along the ranks of portholes, from the ship’s stem to her very stern, and on three of her decks, black, oily smoke started streaming out into the clear winter air. This joined into a cloud, which the morning breeze blew in their direction. Within minutes, the lunching hundreds could smell an acrid, chemical, greasy industrial smoke, heavy and sinister.

The greatest old ship of the British Empire was on fire.

But no fireboats came, not right away. A local accountant was giving his English fiancée’s parents a Sunday boat ride around the harbor, and the four of them stayed, entranced, for three hours. For the first hour no rescue craft came, and they watched with amazement as the blazes consolidated, as explosions began to rock the ship, and as curtains of fire began to race uncontrollably along the vast superstructure. It became swiftly clear that the great liner was doomed to burn, and to sink—and that there were people aboard who needed to be rescued.

It was a full hour before the first fireboats arrived, including the Sir Alexander Grantham, the powerful red-painted vessel that had welcomed the liner six months earlier with vertical jets and curtains of colored water. Instead, today, tens of thousands of gallons of hastily inhaled seawater would be thrust onto the burning ship to drench and protect the police and ambulance crews who were trying to get everyone off her. Which they did, and successfully, even rescuing a worker’s child (who of course should not have been on the ship), who was tied to a rope and lowered over the stern to a waiting tugboat. They also found and took to safety C. H. Tung, C.Y.’s son, who was making a Sunday visit and who would in time inherit the family firm.

No one died that Sunday; nor was anyone badly hurt, except for one man who broke his leg jumping from a porthole and onto a waiting police launch. Nor was anyone hurt the next morning, after all the hoses had been turned off and when the ship was charred black and smoldering and listing alarmingly to starboard, readying herself to founder.

This she did almost precisely at noon, slumping down on her starboard side and into the mud. She died with more of a whimper than a bang, though, with her port-side hull red hot, with fires still burning and setting off dull thumps of explosions that could be heard from deep in her bunkers.

Tung was in Paris at the time, and wept upon hearing the news. In time, insurance paid up eight million dollars, more than twice Tung’s purchase price for the ship, though less than he had spent in total since the ship left her berth in Florida. That insurance payment raised eyebrows; the probable presence of the Triads aboard raised eyebrows; the savage distemper of the Communists in the labor unions working on the ship prompted suspicions; the delay in the fireboats’ arrival led to still more puzzlement; and Hong Kong’s reputation as a sink of corruption made few confident that the obvious two questions—who had done it, and why?—would ever be either properly asked or fully answered.

And this remains the case. All that is certain today, nearly forty years on, is that fires broke out simultaneously in nine different places and that they were deliberately set. But the official reports do not offer a sophisticated conclusion as to who might have set them.* The courts have never decided why or who, and the confidential police file on the matter remains open to this day. Most Cunard officials believe the ship was the victim of sabotage, most probably politically inspired. The Tung family still regards any political motive as wholly improbable.

The ship was scrapped where she lay. About three-quarters of the steel from the wreck was salvaged. Divers employed by a South Korean company worked with acetylene torches to cut her into bite-size chunks, which were then taken away to be smelted into girders for use in Hong Kong’s many new housing projects. Her brassware, screws included, was sold to the Parker Pen Company, and five thousand “QE75” pens were made with brass inlays and nibs, and with a solemnly worded certificate of authenticity from the Tung’s Island Navigation Corporation.

The salvage work became increasingly difficult, as the divers had to venture deeper and deeper—one of them blowing himself up with an accidentally placed gelignite charge—until work was halted in March 1978. Twenty thousand tons of the liner remained buried in the mud south of Tsing Yi Island—including her keel, John Brown’s Keel Number 552, which had formed the enduring base of the largest riveted ship ever made.

For years, her resting place was marked on navigation charts with the green notation that signified a wreck. There was a buoy, and passing mariners were cautioned not to get too close. Then the island near where she sank was expanded with landfill and pilings and cement, and most of the ruined vessel now lies beneath the wharves and walkways and crane tracks of the territory’s main container port.

The saga has an interesting coda, which began to unfold soon after C. Y. Tung’s death in 1982. His son C. H. Tung took over the family’s new-formed shipping company, Orient Overseas Container Line (OOCL), the firm having realized, rightly, that containerization was the wave of the Pacific’s maritime future. But it was not a future the company principals were apparently geared to meet, and the firm soon ran into heavy weather, and needed cash. But—and here is the irony—it was not Taiwan that eventually bailed Tung out, but Communist China. China’s banks loaned him $120 million, and from that moment on, according to one sardonic Hong Kong civil servant, Tung was effectively owned by the mainland party, and henceforward did Beijing’s bidding as his masters saw fit.

They did not wait long to call in his obligations. Britain’s century and a half of sovereignty over Hong Kong would end at midnight on June 30, 1997, and the Chinese would take over. Beijing decided that it would be Tung Chee Hwa (C. H. Tung, newly styled) who would become the first Chinese-appointed chief executive of what would now be called the special administrative region of Hong Kong. Mr. Tung was a shipowner, a man with no knowledge of running a country, or even part of one. But that was perhaps not the point. For, ever since China’s banks bailed him out, he was in China’s debt, and he would be unfailingly loyal.

He had shown this already, in a speech given just one month before the handover of sovereignty. It was a speech that chilled some spines: “Freedom is not unimportant,” he said. “But the West just doesn’t understand Chinese culture. It is time to reaffirm who we are. Individual rights are not as important as order in our society [my emphasis]. That is how we are.”

The Pacific was slowly shifting gears. Those Europeans who had for so long pulled the levers of power in the region were gradually leaving, saying their farewells. A new order was coming to the fore. The United Nations had been eagerly promoting the benefits of decolonization ever since the end of the Second World War, when seven hundred fifty million of the world’s peoples were governed by outsiders and aliens. By the 1970s the old imperial possessions were beginning to shrink like ice cubes on a stove top. New commanders were on the bridge, giving their directions, mouthing their orders, dictating the region’s future with either caution or swiftness or relief, according to their own devices. On great ships, on tiny islands, and along exotic coastlines, all around.

This new order produced many farewells, some poignant, others lethally violent. The sabotaging of the great British ocean liner, and the elevation to power of a man who was so intimately involved with her fate, serve as a potent symbol—but as a symbol only. Other farewells were very much more savage, and some had global repercussions. The most notoriously dramatic and costliest of these had to be the enforced departure of the Americans from Vietnam in the spring of 1975. For it was only then, and after more than a century, that the various states* of Indochina, bastions of the western Pacific hinterland, were at last able to rule themselves again. Foreign domination had utterly defined the recent history of the Southeast Asian peninsula. But the process of restoring governance to the various Indochinese peoples (the Vietnamese, the Lao, and the Khmer) was a far more protracted business than the infamous nine years of America’s own ill-judged involvement there, which cost the lives of fifty-eight thousand of its young men and women, and two million or more of those who claimed these countries as their own.

The French had ruled in Indochina—had owned Indochina, as colonists like to claim—ever since their capture of Saigon in 1859. Though the French were as imperially oppressive as any, they are generally seen today as having been more benign and cultured than such philistine ruffians as the Dutch and the British, and the legacy of their sovereignty—a local fondness for wine; the number of surviving boulangeries; the pidgin French still heard there in the cities from Hanoi to Luang Prabang, from Kompong Som to Hue—is still well thought of, and offers to yesterday’s “Indochine” a veneer of exotic and erotic Eastern chic. Even so, all empires, benign or brutal, inevitably fade, and the drawing down of French influence in South East Asia would get under way swiftly, soon after the Second World War.

It is conventional to see France’s humiliating defeat at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu in far northern Vietnam in 1954 as the beginning of the end of France’s land tenure in the western Pacific. But one other episode, half-forgotten now, marks the ultimate cause of the whole unlovely mess, of which Dien Bien Phu was but one part. It occurred in 1945, and it concerns a much-decorated British Indian Army officer named Douglas David Gracey. The strange events that briefly enfolded him offer invaluable context for what would occur in the years following.

For Major General Gracey had been handed the unusual, unprecedented appointment, at the Pacific War’s end, of commander in chief, Allied Land Forces French Indochina. He was dispatched to Saigon—a senior British army officer from India ordered to preside over a French colony that was at the time occupied by defeated Japanese invaders must surely be one of the more curious pieces of political flotsam to wash up in the wake of war. Gracey was aware of the sensitivities of the situation: for six heady months, and from a hastily built British military headquarters in southern Vietnam, he directed his twenty thousand soldiers through one of the most bizarre periods in modern Indochinese history—with the specific avowed aim (since restoring the imperial status quo was Winston Churchill’s stated policy) of returning the territory to the imperial rule of the French. His expedition’s name was Operation Masterdom.

Gracey and his troops had been ordered into Saigon because those Allied politicians who in 1945 were planning Indochina’s fate—a peripheral issue in the Potsdam Conference, held after victory was ensured in Europe—had been blindsided by Japan’s unexpectedly swift surrender. Vietnam had long been occupied by Japan, and now the Japanese soldiers involved in the mechanics of that occupation had all to be disarmed and packed off home, much as their brother soldiers were to be sent home from various other places in the Pacific.

But what Gracey had not expected was the impassioned opposition to his mission by the Viet Minh nationalists in Saigon.* No matter that he was there to turf out the Japanese occupiers: as soon as he arrived, in September 1945, he noted that the road from the Saigon airport was lined with people waving Viet Minh flags and holding posters that supposedly welcomed him and his forces, but that demanded also that the French colonists leave. Since British policy (Churchill’s policy) was precisely the opposite, Gracey smelled trouble.

He first refused point-blank to cooperate with the Viet Minh. His job, as he saw it, was simply to free all Allied prisoners of war, to ease the French back into running the country, and to get the Japanese garrisons out of the country. The Viet Minh did not take kindly to the general’s insouciantly dismissive attitude. They staged strikes and closed down the Saigon market. Gracey retaliated by shutting down the newspapers; declaring what was effectively martial law; and freeing a particularly violent group of former French soldiers, who promptly armed themselves, initiated a citywide version of a coup d’état, and embarked on acts of vengeance against everyone who stood in their way—Viet Minh nationalists most especially.

Fighting erupted, and quickly spread everywhere. Gracey and his infantrymen and his kukri-wielding Gurkha battalions from Nepal, tore into the fight with gusto. His superiors back in Singapore told him to stop, saying the battles were none of his business, were nothing to do with Britain. But such was the ferocity of some of the attacks (one of them with rifles, spears, and poisoned arrows) on British positions that he was eventually given carte blanche and told his new duty was to “pacify” the region.

That’s when Gracey made one of the most curious of all postwar decisions, aware that because he had not had time to ship them out, he had thousands of disarmed Japanese troops still in the area. Since they knew the city and knew how to fight, Gracey gave them guns and demanded that they stand alongside his British soldiers against the Viet Minh nationalists.

Of all the many bizarreries of the time, this was among the most extreme. The notion that Japanese troops would be armed by those who had recently vanquished them and that they would then be compelled to fight under a British flag alongside Nepalese soldiers for a French colonial ideal against a Vietnamese force that was demanding its own people’s independence is well-nigh incomprehensible.

But it worked. With the help of the Japanese—“they did their job with characteristic efficiency,” said one Gurkha officer, noting, in addition, that they may have reduced “casualties among our own troops”—the British did in the end succeed in pacifying the region.

By October, matters had quieted down enough that the French could indeed return, as Churchill had ordered. The magnificently aristocratic French general Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque assumed the reins in Saigon, and early in 1946, Major General Gracey was able to conclude his tenure in Vietnam, to take his soldiers back with him to India, and to resume something of a quiet life.*

Unwittingly, though, Gracey had so angered the Viet Minh by his disdain, his arrogance, and his brutal battles against them that some insist it was he who case-hardened Ho Chi Minh’s opposition to the West, and indeed to all continued Western interest in the region. Ho’s opposition to all future outside interference in Indochina became, from that time onward, unyielding, implacable. Critics of Gracey’s “ruthless” and “overtly political” pacification campaign have long blamed him for standing in the way of what could have been peaceful progress to self-government.

The Vietnamese path to independence, of shedding their submission to a European power, was long and bloody. The Vietnamese today speak of the First and the Second Indochina Wars—the first, pitting the Viet Minh against the French; the second, pitting Vietnam’s North against its South, with the Americans in this case heavily and vainly trying to keep the two young countries from becoming dominated by Communists. The fighting involved in both wars lasted for thirty years. The first war cost 500,000 Vietnamese lives and 90,000 French. The second resulted in more than 1 million North Vietnamese dead, 200,000 South Vietnamese, more than 58,000 Americans, and an assortment (Australian, Koreans, Thais) of more than 5,000 others. All told, well over 1.5 million Vietnamese died, and well over 160,000 Europeans and Americans—and in the end, the Indochinese were fully back in control of their own affairs.

The way stations of the two conflicts are fading fast along history’s conveyor belt. Some of the names and events once so famed have receded with pitiless speed. Who now recalls Bao Dai, the perfumed and bejeweled final emperor of Annam, the last ruler of the Nguyen dynasty, who gave Vietnam its name and who was a puppet of the French, more famous in Monte Carlo than he ever was in the valleys of the Mekong or the Red River? What is now known of the Navarre Plan of 1953, a scheme by which the French had hoped to win back their influence from the guerrilla armies of the Viet Minh, and which was formally approved by the American headquarters in Hawaii? Do any now recall General Francis Brink, the Cornell-educated American infantryman who headed the first-ever U.S. Army headquarters in Saigon, established back in August 1950—and who shot himself an improbable three times in the chest in his office at the Pentagon because, the army said later, he was depressed? Questions about what drove him to his death—or of how anyone could shoot himself three times, anywhere—have surfaced now and then; but General Brink’s medical records were accidentally burned, and the suggestion that he stumbled on some misappropriation of funds or the smuggling of drugs, and was silenced, has been discounted and, like so much else from Vietnam, forgotten.

Dien Bien Phu lingers somewhat in the memory, though. In November 1953, three battalions of French paratroopers dropped from squadrons of aircraft, and established their new fortress in a long valley on the border with Laos. Within weeks this swath of low-lying territory had been transformed into a formidable-looking base. There were two long airstrips, scores of gun emplacements, and subsidiary hilltop forts with winsome female names such as Beatrice, Huguette, Gabrielle, Claudine, and Eliane—which were supposed to help win the support of the war-weary citoyens back home, but which actually did the opposite.

Ho Chi Minh had the measure of the giant base almost from the start. It was said that he once took his topee from his head and turned it upside down. He thrust his fist into the concavity: “[T]he French are here.” Then, with a sly grin, he traced his fingernail around the rim: “[A]nd we are here.”

His equally sly military commander, Vo Nguyen Giap, had been preparing for weeks, bringing in artillery pieces bolt by bolt, trunnion by trunnion, barrel by barrel, along the maze of jungle paths. In total silence his soldiers dug rabbit warrens of trenches to within feet of the French lines. And once the howitzers up on the hillsides had been trained and the trench mortars readied, on March 13, 1954, one of the greatest, saddest, most heroic, most Orientally impudent and Asiatically triumphant battles of recent times got under way.

At a signal from Giap, a thunderous artillery barrage was unleashed from up on the surrounding hilltops, announcing an assault that would go on, uninterrupted, for a horrendously lethal fifty-four days. Day by day the French were pushed into what must have seemed like the unforgiving jaws of a meat grinder. Discipline held, and there were heroic displays that have never been forgotten in France to this day. But it was hopeless. The position was entirely surrounded; the odds, overwhelming.

The French artillery commander committed suicide, killing himself with a grenade for bringing dishonor (as a Frenchman naturally would put it) to his country. The most senior French general was captured in his bunker, well-nigh unimaginably. So desperate was the situation that brief consideration was given to asking the Americans to use tactical atomic weapons, to help drive the unstoppable Viet Minh away.

But that never happened; and for all its ardor, the fighting by the French turned out to be, essentially, all for nothing. They finally surrendered when their last central redoubt was overrun by Viet Minh troops at 5:30 p.m. on Friday, May 7, 1954. The very next day, the topic of Indochina was formally added to the agenda of the Korean War peace conference that was under way in Geneva; and there, in full view of the international community, the French announced their formal withdrawal from all of Indochina. They were done. They were out.

More ominously, the conferees also then divided Vietnam into two. A demilitarized zone was established around the Seventeenth Parallel. To its north were Ho Chi Minh and Vo Nguyen Giap and their Democratic Republic of Vietnam, a brand-new state that was now backed by Moscow and Beijing. To its south was the State of Vietnam, nominally ruled by Emperor Bao Dai, but in effect run by the United States and its chosen surrogates. The mutual hostility between the two states simmered through the remainder of the fifties; there were insurrections and outbreaks of dissidence and monkish demonstrations and assassinations, met with so swift a gathering of support from Washington that President John F. Kennedy was formally warned he was doing no more than replacing the French, and that he was likely to bleed just as badly as they had bled.

But both he and his successor ignored the advice; and on the flimsiest of pretexts, President Lyndon Johnson won congressional approval in the summer of 1964 to send troops to Vietnam without any formal declaration of war. American involvement in the heartache of the Second Indochinese War accelerated mightily from that moment onward. Yet the arc of progress for this conflict ended just as it had for the French, and just as Kennedy had been warned: with defeat, withdrawal, collapse, and humiliation.

The way stations and the dramatis personae of this second war were once familiar icons written in universally known shorthand—there was the Ho Chi Minh Trail, there was Operation Rolling Thunder, there was the My Lai Massacre, Agent Orange, Khe Sanh, the Siege of Hue, the Tet Offensive, Hamburger Hill, Da Trang, William Westmoreland, Hanoi Jane, Le Duc Tho, Operation Linebacker, the Cambodian evacuation operation known as Eagle Pull, and its Saigon equivalent Operation Frequent Wind. Many of these people, places, or events have now to be looked up in indexes; and as one generation is succeeded by the next, those who struggle to remember are fast being overturned by those who never knew. Sixty percent of today’s Americans were unborn when the war came to its end. It was not entirely incredible when some late-night comedian remarked that a sizable number of modern high school students fully believe that the Vietnam War was fought against the Germans.

Nine million American men and women served in the military in Vietnam. At the fighting’s bitterest, in 1968, more than half a million American troops were in the country. Thereafter, as domestic distaste for the conflict grew, the numbers began to drop, by many tens of thousands every year—until, at the very end, at the close of 1974, just fifty soldiers and marines remained. And then Operation Frequent Wind was staged in the final days of April 1975, to get those final fifty out, and to collect all available others and their friends, and to bring America’s formal role in Indochina to its sorry conclusion.

The last American hours of Saigon in 1975 were both wretched and poignant. Even the most Panglossian in the capital knew that their city, by then quite surrounded by Viet Cong army units, was about to fall. Elaborate plans had been laid for a helicopter evacuation of all remaining Americans and those friends and helpers and foreign journalists who were known as “at-risk aliens.” Booklets were published with instructions, to be kept as secret as possible: if a radio broadcast began with the phrase “The temperature in Saigon is 112 degrees and rising,” and was followed by thirty seconds of Bing Crosby singing “I’m Dreaming of a White Christmas,”* then it was time to go, with all deliberate speed, to one of a dozen designated spots where U.S. Marine Corps and Air America helicopters would be waiting.

But over the din of shellfire and shouting, few in Saigon heard the broadcast; fewer still understood it. Rumors spread wildly. Thousands crowded the landing zones, panic-stricken, frantic, desperate. Previously chosen landing sites came under fire; new sites had to be found in double-quick time—marines were to be seen cutting down tamarind trees to clear the way for the giant flying machines, which came stuttering to the city every few minutes, from a mighty armada of ships hurriedly assembled twenty miles out in the Pacific. The American ambassador was one of the last to go, shortly before 5:00 a.m. on Wednesday, April 30. “Tiger is out” was the coded signal, meaning that the American official presence was officially at an end.

Except that it wasn’t. Someone had forgotten to collect the ten remaining marine bodyguards, and a final helicopter had to be sent for them. At 7:53 a.m. this final machine took off; and at 8:30 a.m. it landed aboard the amphibious assault ship USS Okinawa.

Helicopters employed in the final frantic hours of the evacuation of Saigon were tipped into the Pacific, useless symbols of American power squandered in the hopeless quagmire of an end-of-empire war that should never have been fought.

U.S. Marine Corps.

Three hours later, precisely, North Vietnamese tanks smashed through the gates of the Presidential Palace and raised the Viet Cong flag.

Western occupation of the continental coastline of the far western Pacific was now, after 175 years, at an end. Those foreigners who would later come to this part of the world would do so only by invitation, and with the permission of those whose land it was now, at last.

The Pacific’s British colonists, by contrast, departed with rather less fuss. Instead of being run out on a rail as the Americans had been in Southeast Asia (and as had the French, Germans, and Japanese), they went like the country house guests who, on a muffled cough from the butler, suddenly realize they have overstayed their welcome. So they leave in a state of mild confusion, dropping things, tripping over their shoelaces, shutting their fingers in doors, and saying to their beaming hosts all too many farewells, in their embarrassed and befuddled haste to get away.

Until the 1970s, maps of the Pacific, like those of the rest of the world, were still awash with British imperial pink. The legatees of Captain Cook and Stamford Raffles still reigned over tiny but critical morsels of land in the ocean west of the dateline. This meant that British officials governed untold numbers of dark-skinned native peoples—Kipling’s “lesser breeds without the law.” Britain’s islands there were never to be abandoned, never to be forsaken. They were a reminder of what John Milton had once called England’s “precedence of teaching nations how to live.” This notion recalls the old joke of many a 1950s mother, who would tell her irregular child to eat prunes because the fruit had much in common with British missionaries in these parts: since prunes, like missionaries, “go into dark interiors and do good works.”

Malaya, Singapore, Papua New Guinea,* Brunei, Sarawak, and North Borneo—they all form the fortress of the western flank. Then, farther eastward and out at sea, there are the poster children of Britain’s blue-water Pacific empire: the Gilbert Islands, the Ellice Islands, the Solomons, the New Hebrides, and Ocean Island. More distant still are the lonelier imperial holdings: Fiji, Tonga, and the Pitcairn Group. Finally, up north, alone and presiding magisterially over all else in the Pacific, is Hong Kong, an outpost of Britishness then little more than a century old, quite alone on the underbelly of China, looking especially vulnerable and impermanent. Few in the 1970s, though, could imagine just how little time was left.

So far as Britain’s long invigilation in the region was concerned, the clock was now ticking, insistently. There were three essential reasons. London’s treasuries had been emptied by the Second World War, and it had become too expensive to maintain all the imperial flummery and panjandrumry around the world. In the new, postwar world, there was a growing feeling that empires were unfair, immoral, and unfashionable, and this led to stirrings of revolt and disaffection among more than a few of the ruled peoples. All of a sudden London was facing the gnawing realization that this empire really had to be brought to an end.

A program for the empire’s divestment was devised, and the whole carelessly assembled confection of countries, enclaves, islands, lighthouses, and reefs and redoubts, on which no sun had set for scores of years, was let go, and Britain started to ease herself out.

Malaya was the first to go. The Duke of Gloucester came and read a message from his niece, Queen Elizabeth, wishing all the Malays deserved good fortune. The British rulers of North Borneo then packed for home six years later. Then, out at sea, the various colonial entities that occupied the 2.5 million square miles of ocean (and about ten thousand square miles of land within it) that were ruled as one by the British High Commissioner, as his full title had it, “in, over and for the Western Pacific Islands,” were given their independences in stages.

One of them, the Kingdom of Tonga, a centuries-old monarchy that had been under British protection since 1900, wrested itself free of this most cumbersome arrangement in 1970. So, too, did Fiji: Prince Charles did the honors there, though he was four hours late because his royal plane broke down in Bahrain. He was given twelve live Fijian turtles as a gift, and a set of gold cuff links. The prince said he was glad they hadn’t given him a silver spoon, since he and his siblings had been born with those already. As it happened, the violence for which the Fijian islands had long been known—the fork used to eat the Reverend Mr. Baker is still in a display case in the Fiji Museum—was perpetuated in postcolonial times, with coups d’état and constitutional crises on a heroic scale.

The imperial crown jewels of the Western Pacific, the Gilbert and Ellice Islands, achieved their self-rule in 1976. They had been an immense Pacific possession of two million square miles, first made famous abroad by their former governor Arthur Grimble and his 1932 book, A Pattern of Islands, about running them—every British schoolboy raised in the 1950s knew passages from this classic book by heart and by jingo! The island groups had been stitched together for reasons of London’s administrative convenience—notwithstanding the fact that the Gilberts were populated by Micronesians and the Ellices by Polynesians, peoples not always on the friendliest of terms. So once the islanders scented the merest whiff of freedom, they voted to break away, not just from Britain but from each other. Today the former are known as Kiribati and the latter as Tuvalu, separate entities in the wide and decidedly non-British Pacific.

The British Solomon Islands Protectorate—best known in America either for the savage fighting on Guadalcanal or for being, during their wartime occupation by the Japanese, the place where Lieutenant John F. Kennedy was shipwrecked and where he carved the famous message on a coconut that led to his rescue—then became independent in 1978. (The American astronaut John Glenn, who had served as a marine in the South Pacific, was part of the celebrations.)

The New Hebrides, nearby, went two years after. Since 1906 these islands had been run for complicated reasons by a condominium of two uninvited European powers, the British and French. Two bureaucracies had been set up, exactly mirroring each other—the French official in charge of drains in Port-Vila, for example, had a British counterpart who was charged with exactly the same task.

The language of New Hebridean administration had to be translated twice, Canadian style, and sometime thrice, since the doubly colonized citizens actually spoke a third, Creole tongue called Bislama, and many of the territory’s more important legal documents had to be rendered into its mysteries as well. The colony’s laws were in consequence a magnificent mess: any New Hebridean could choose to be tried or to sue under either Napoleonic or Magna Cartan legal principles, or else by Melanesian local law in a native court—the chief justice of which was appointed by the nominally neutral king of Spain.

Two police forces, their officers wearing different uniforms, did their best to keep civil order in turns, performing their respective duties on every other day. (History does not record which police officers were the more lenient.) Finance was exceptionally cumbersome—French francs and British pounds sterling being interchangeable, Australian money accepted, and banknotes issued by the Paris-based Bank of Indochina in stores everywhere. National holidays were so numerous and so keenly celebrated in the perpetually torrid climate that little work was performed anyway—and in time, the whole unholy and intractable mess of governance exhausted everyone, collapsed internally, and was finally called to a halt in 1980, with the new and present entity being called Vanuatu. The French, who had wanted to retain a foothold in this corner of the ocean, sulked mightily when independence was eventually declared, and their officials stormed away from the islands with all their telephones, radios, and air-conditioning units, in a display of official petulance seldom rivaled.*

In the wider Pacific, foreign empires were nearly all done with by the 1990s, after this two-decade cascade of self-determination. Only one pair of imperially run places of significance then remained. By happenstance they were places that in all senses were the polar opposites of each other—and both of them were British.

One was the hugely populous, hugely rich, and world-renowned colony of Hong Kong. Four hundred square miles in extent, it was a crowded mountain home to six million people, most of them Cantonese-speaking Chinese, administered as they’d been since the middle of the nineteenth century by a tiny and privileged corps of very British diplomats, civil servants, and politicians.

The other was the tiny (just two square miles) Pitcairn Island group, which was hardly populated at all, a starveling child of empire (since 1838) with fewer than sixty people. It remains a persistent and unwanted colony today; and though its origins as the refuge of the nine men who, under Fletcher Christian’s leadership, mutinied in 1789 against Captain Bligh and his captaincy of HMS Bounty are seen by some as the stuff of swashbuckling romance, its present situation has been clouded by a deeply unedifying scandal.

I first visited Pitcairn in 1992, by courtesy of the New Zealand captain of the HMNZS Canterbury, who gave me a ride on his frigate as she was making her way from Auckland to Liverpool to take part in a naval review to mark the queen’s fortieth jubilee.

We took ten days to reach the island—the colony in fact comprises four: Pitcairn itself, together with nearby Henderson, and then the further atolls of Ducie and Oeno, each about a hundred miles from the others. We saw not a single ship on our passage, sliding into an ever-lonelier sea each day that we pressed farther eastward.

Finally we spotted Pitcairn, a tiny speck of green volcanic hills that rose abruptly out of an otherwise empty tropical ocean. We were met by a flotilla of longboats. Islanders are always on the watch for any sign on the horizon that might suggest an approaching ship; when they saw us, dozens of miles away, they launched every craft available to make sure as many of them as possible got to see a modern ship of war—which, after all, was what the Bounty, burned to the waterline but still vaguely visible, had been.

We surfed in, dangerously, to the tiny concrete pier. I walked, painfully, up the viciously steep Hill of Difficulty, the one approach to the colony’s small shanty settlement of Adamstown. There was not the vaguest hint of anything untoward. The island was warm, sleepy, friendly. The walking—up and down red laterite roads onto green peaks from which all else was blue, an empty, cloudless pale blue sky and an empty, shipless deep blue ocean—was wearying, hot, lonely.

But there were always stories to be found. At the top of one hill, for instance, I met a Japanese man with a pup tent and a large radio transmitter: he was a ham operator who had come to Pitcairn to broadcast messages and persuade those who heard him to write the so-called QSL “I have heard your transmission” cards, asking for a dollar or so each time in return. People had sent him ten thousand dollars thus far, he said, and felt it was time to go home. Could we take him on to Panama? The captain said no. The Japanese man, only a little crestfallen, crawled back into his tent with a book. He said he was content to wait for another passing ship, maybe in a month or so.

There was a pineapple plantation in a nearby meadow, and a couple of Pitcairners with a Cryovac food packaging machine told how they once had had plans for exporting air-dried pineapple to the outside world. But then the French resumed testing nuclear weapons on Mururoa Atoll, six hundred miles to the west; and even though the prevailing winds were blowing away from Pitcairn, such of the world as might perhaps have been interested in buying Pitcairn pineapples decided, in short order, that Ecuadorian and Philippine pineapples were safer bets, less likely to be radioactive. Later experiments with Pitcairn honey—a New Zealand beekeeper was brought in to offer training—proved more successful, though; and Bounty products can be seen today in high-end grocery stores in London. Otherwise, only the sale of postage stamps and of carvings made from the rock-hard miro wood found on Henderson Island* provide some islanders with a modest income. The island government, such as it is, canvasses for outsiders to come and settle. Few have taken the bait.

The recent scandal hasn’t helped. It started to unfold in 1999, when a young female police officer from England was sent out to Pitcairn (which had never had a regular police force) for a six-month training exercise and discovered a widespread culture of sexual abuse. It seems that Pitcairn men regularly had sex with girls as young as ten, and it was not uncommon for girls to have their first pregnancies when they were as young as twelve. The islanders said they saw nothing unusual or improper about the practice, and claimed they were following established Polynesian custom—the British mutineers having brought Tahitian wives with them in 1789, and the island stock ever since being an admixture of Anglo-Pacific genes and cultures.

When the police officer reported her findings, the British courts were not so understanding. Detectives promptly descended on the Pitcairn community; then lawyers—some to be involved in historical challenges over exactly who had sovereignty and legal jurisdiction over an island that had only infrequently paid more than lip service to any legal system at all—began what would amount to a five-year field day.

Victims were found. Witnesses were identified. Charges were brought. Seven men, including the island mayor and longboat coxswain Steve Christian, a direct descendant of Fletcher Christian, were arrested. It was first argued that the case should be heard in New Zealand, but the courts decided it should be heard on Pitcairn—with the result that more judges, lawyers, witnesses, and reporters suddenly arrived in Adamstown to take part in the trial than lived in Adamstown in the first place. A satellite system was set up so that witnesses could testify remotely—it turned out that every one of the women involved now lived overseas. All the islanders’ guns were confiscated, to prevent any possibility of violence on an island that was now bitterly divided over the issue.

The trial took forty days and cost some twelve million dollars. There was then a series of appeals, which wound their steady and convoluted way through the maze of the British legal system, right up to the then-supreme authority of the Privy Council in Buckingham Palace, which summarily rejected them. Six of the seven men charged were then sentenced to prison—except there was no prison on Pitcairn, and one had to be specially built.

Fears were promptly expressed by many in Adamstown that the whole affair was a devilish plot that would enable Britain to get rid of the costly annoyance that was Pitcairn. For the six able-bodied men put in jail would now not be able to man the longboats that brought in vital cargo from the island supply ships—with the result that the settlement would wither and die, and the remaining islanders would head west to join the refugees from an earlier crisis (a famine, and overcrowding in 1856) on the former prison colony of Norfolk Island, off the Queensland coast.

But wiser counsels prevailed. The men were locked into their cells in a jail they built themselves, from a prefabricated prison kit sent down from Britain. But every time a ship hove to off the island to unload cargo, the men were briefly freed (supervised by corrections officers) and paid to get out the island longboats and transfer goods to the quayside. After which they were marched back up the Hill of Difficulty and into their cells, and locked in again until the next smudge of smoke was spotted on the horizon.

All six men eventually served out their sentences and were released back into the population. Since only one woman on the island is currently of childbearing age, and since these six presumably still fertile men are bound over to be exceptionally well behaved, it is now gloomily assumed that the colony of Pitcairn will wither and die anyway.

Until it does—most demographers believe it can last only until about 2030—some small number of tourists will come, once in a while, to see the relics of the famous mutiny: HMS Bounty’s anchor, her Bible, and her cannon. They will sample the local honey. They will buy tchotchkes made of miro wood and postcards with postage stamps. And they will stay in the newly made but quite empty jail—which, since it is one of the few structures on Pitcairn to have proper plumbing, is thought best used as a guesthouse. And those who visit this most remote outpost of Britain’s former empire in the Pacific may choose to reflect, and wistfully, on the droll reality: that a place with such a lawless and inglorious beginning is now suffering, as a consequence of lawlessness, an inelegant and inglorious end.

An end rather less celebrated and memorialized than that of its polar opposite in the Pacific, eight thousand miles farther northwest: Hong Kong.

It was only toward the very end of London’s rule in the southern Pacific that those in the one colony in the northern Pacific started to question their own status. Hong Kong’s bankers in particular began to fret—especially those who held or gave or thought themselves likely to extend mortgages, fifteen-year mortgages most commonly. These anxious moneymen started to ask a simple but obvious question: would those mortgages still be valid after fifteen years if the government of Hong Kong were no longer capitalist and British, but Chinese and doctrinally Communist?

They began asking this question in the spring of 1979, because fifteen years from that time very roughly spelled the date, in small print, on the half-forgotten last treaty that the British and Chinese had signed together, a treaty that, most important, had said that a major part of Hong Kong’s territory was to be ruled by the British as a lease. The document had been signed in June 1898. The lease was for ninety-nine years. The bankers were wise enough to know what many ordinary colonial citizens had forgotten, had never known, or had chosen to ignore: that this lease would expire at midnight on June 30, 1997.

So the question the bankers wanted answered was: were the Chinese going to extend the deadline and allow Hong Kong to remain under British rule for some long and indefinable period far into the future?

The bankers asked the then-governor of Hong Kong, Murray MacLehose, to put this question to his Chinese counterparts in the Chinese capital, in what was then generally known as Peking. His Excellency duly flew there and was given banquets and taken to the Great Wall, the Winter Palace, and the Forbidden City and was accorded appropriate respect. And he got the answer to the bankers’ question, from Deng Xiaoping, the Chinese leader at the time. It was not what he, the bankers, or anyone else in the colony wanted to hear.

There was absolutely no question, the diminutive Deng declared, of extending any lease. Hong Kong was most assuredly being shepherded back to its motherland. The Chinese wanted all of their territory returned. They wanted the New Territories. They wanted Kowloon. They wanted Hong Kong Island. They wanted, in short, everything. There was no point in any clever British lawyers spluttering that the three treaties signed during Victorian times gave some of the territory to Britain in perpetuity. As far as Deng Xiaoping was concerned, all three treaties were unequal and unfair, had no standing in law or modern reality, and could be torn up and turned into confetti at will. Deng insisted that everyone understand that Hong Kong’s existence as a British overseas territory was coming to an end. June 30, 1997, was the fixed date when the bills came due. The timer was running down. Talks had better get under way to sort out the details.

The only thing that gave MacLehose any kind of reassurance was a phrase from Deng, uttered just before the pair made their farewells, and that the British governor then went on to repeat endlessly to the nervous, skittish, unhappy millions he greeted upon his return home, after flying over the dark plains of China to the brilliantly lit jewel that was his colony: “Set your hearts at ease.” He said it a score of times. It was what the Chinese leader had asked him to tell Chinese citizenry down in Hong Kong. “Set your hearts at ease.”

Yet this mantra was not at all helpful. The next years for Hong Kong would be an agony of a thousand cuts. Talks did indeed get under way, but they were dispiriting affairs. I flew to the Chinese capital for one of the earliest sessions, a mid-level British ministerial mission designed to prepare the ground for a visit the following year by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. Ordinarily, if Britain has influence in such talks, they have a sense of style, brio, confidence, fun, purpose. But what I watched in Beijing was more like a solemn requiem in the key of gray, played out in the bitter cold of a northern Chinese winter week.

The city was a place of dreary monochrome—and was gritty, cold, smoky, unnaturally quiet, as if everyone were half-hidden and spoke in whispers. This, in 1981, was the neon-less, barely prosperous, cold-comfort Communist China of quite another era: there were armies of bicycles everywhere; clusters of soldiers huddling for warmth around street corner coke burners, seething masses of laborers in hutongs of amiable slums; with hugger-mugger gatherings of workers clad in gray or dark-blue Mao suits and with exhortative Communist slogans everywhere.

The officials who came in from Britain, men and women likewise swathed in gray (though some wore Savile Row pinstripes) would meet each day with lantern-jawed officials from the Chinese ministries, and then retire to their miserable gray-painted rooms in a huge gray-walled hotel on Chang’an Avenue, just along from Tiananmen Square. Each evening they seemed listless, unimpressive, puny—and to the extent that they talked out of school, it was to express their disappointment that the Chinese would not budge, would not agree to any kind of compromise or concession.

When Mrs. Thatcher came to China, she looked puny and unimpressive, too, and she proved no match for her Chinese counterpart. She winced visibly when Deng told her in undiplomatic terms that he could march into Hong Kong anytime he wanted, and retake it in an afternoon if he was so minded—the implication being that he was doing her a considerable favor by restraining himself from doing so. Whatever the tenor of her retort, the spirit gods were not with her that day, for on her way out of the meeting, she tripped and fell onto the steps of the Great Hall of the People in a mess of gabardine and mussed hair, looking vulnerable and weak as she was hoisted upright again by her team of men in gray.

Back at home, she may still have cut a heroic figure, fresh from having had her soldiers win the return of the Falkland Islands from their Argentine invaders. But this did not interest Mr. Deng. Not one whit. This Pacific colony was not one she was going to win back from history or from him, now or ever.

This somber fact was eventually formalized by a joint declaration of the British and Chinese governments, made public shortly before Christmas 1984. All knew such a statement was coming, but a number of Hong Kong government officials wept openly at hearing the words. The only way of life they had ever known was coming to an end. Soothing nostrums were offered, suggesting that nothing would change, but everyone shrewd enough in matters Chinese knew that everything would, slowly but surely.

A mood of deep pessimism then settled on the territory—especially now that the Tiananmen Square demonstrations in 1989 that ended with the killings of so very many protesters had reminded residents of the terrors of totalitarianism. Over the next several years, thousands of Hong Kong residents were prompted to leave; to settle in Canada, Australia, the United States, and, to a lesser extent than seemed proper, the United Kingdom, which did not exactly open wide its doors to its nonwhite colonial subjects.*

Embassies and consulates in Hong Kong were thronged with visa applications. The lines outside the U.S. consulate snaked uphill for hundreds of yards. Sixty thousand people left in 1992. Parts of Vancouver changed their appearance almost overnight: sedate suburban houses on the airport road, which for decades had looked as though transplanted from Tunbridge Wells, were sold to fleeing Hong Kongers for many times their asking price. They were then torn down and replaced by enormous mansions, all marble and onyx, without the fringing flower gardens for which the newcomers had no use.

As 1997 approached, an enormous digital clock was set up in Tiananmen Square, counting down the days and hours until the completion of what most people called “the handover.” (Official London called it “the retrocession.”) Fireworks were prepared, and local Beijing residents were urged to celebrate the territory’s return to the motherland after its century and a half away. Not a single Chinese could be found who wished the territory to remain British—and small wonder. Hong Kong, after all, was one of the spoils of the Opium Wars, a legatee of the time when cocksure Britain had tempted the impoverished Chinese with cheap drugs from India and then reacted violently when the emperor tried to ban the commerce, and had used warships and overwhelming force to press home the British right to trade.

In Hong Kong the approach of its tryst with destiny—to use Nehru’s phrase in independent India, won from the British exactly a half century before—was regarded very differently. Few in the territory could be found who regarded with equanimity the ticking down of the clock, and as hot April became sweaty May and then sweltering June, there was widespread apprehension that something, unspecified but ominous, would occur when the deadline passed. Television journalists flooded in from all over the world, and there were scaremongers among them, who spoke of seeing Chinese heavy armor on the far side of the border, wild-eyed men of the kind who had perpetrated the Tiananmen tragedy eight years before, massing beyond the wire and ready to storm in and make dreadful mischief once the territory was restored.

The British took months to pack and get ready to leave. I watched many of the details, most especially those involving the military, always a great component of maintaining any empire. Ammunition, thousands of tons of naval artillery shells and torpedoes, was taken from the tunnels on Stonecutters Island and put on ships to go back to armories in England. The Sikh security men who had acted as its guards for generations (chosen to preside over flammable explosives because of their absolute religious prohibition on smoking) were offered jobs elsewhere. (Local hotels liked to employ Sikh doormen because of their magnificent, guest-impressing headgear.)

Likewise, thousands of Gurkha soldiers were stood down, and most of those who chose not to go home to Nepal were employed as security guards by one of the British firms that planned to remain in the territory post-handover. The doughty little motor yacht that used to take the official with the job of “District Officer, Islands,” on his enviable inspection tours of the scores of little rocks and their fishing communities in his imperial charge, had its Union Jack replaced by a burgee sporting the insignia of the bauhinia, a sterile, orchid-like flower.

The last keeper of the Waglan Island Lighthouse was retired and replaced by a machine: a sorry fate, though it meant that the “Light at the End of the Empire,” as we all knew the summit tower on the colony’s eastern tip, would continue to shine out long after its owners had departed, winking its reassurance to ships gliding into and out of one of the world’s busiest and richest ports.

The British Forces Broadcasting Service transmitters were unbolted from their barrack block studios, where they had been transmitting to British soldiers and sailors since 1945, and moved onto a waiting destroyer. The plan was to continue to broadcast until midnight, when the ship would leave Hong Kong waters and the station’s final refrain (the national anthem, or maybe Vera Lynn’s “White Cliffs of Dover”) would fade into the ether as the craft moved away to sea.

The royal yacht Britannia arrived in port, in the very last few days of British rule, tasked to take away Prince Charles and the governor and the various diplomats and officials who would participate in the final ceremonials. The weather on the afternoon and evening of June 30 was ferocious, and driving tropical rain and wind turned Britain’s final sunset military parade into a soggy maelstrom of misery, with the symbolism not lost on either side—either the skies were weeping for the departure of the British or the winds were raging to drive them from the scene.

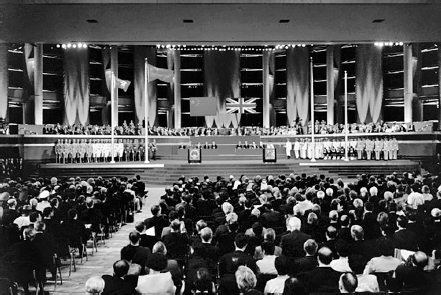

The ceremony of the transfer of sovereignty, choreographed to the microsecond around the midnight hour, was sturdily impressive. The Chinese leadership had been flown in from Beijing by 747. Some five hundred truckloads of Chinese soldiers came across the border three hours before the deadline. The tallest and best dressed of them took part in a performance of crisp goose-stepping discipline that was as chilling as it was majestic. And when they raised their national flag, the pictures, transmitted live onto giant screens a thousand miles to the north, prompted Tiananmen Square to erupt in paroxysms (whether enforced is still not known) of fireworks and wild enthusiasm. The British forces who then took part in the flag lowering, moments before midnight, looked by contrast worn, weary, and unkempt, their uniforms still damp from the rainstorm, their performance to be seen as either shabbily charming or unhappily threadbare.

The June 1997 night of Hong Kong’s long-awaited “retrocession” from the British Empire was cold and rainswept, drenching the ceremonial and those who attended, and making for an unseemly end to Britain’s presence in the North Pacific.

FormAsia.

Once the flag was down, Hong Kong was no longer a British colony; and the governor’s formal telegram was transmitted to the queen, a relinquishment done, the retrocession achieved, the ills of the Opium Wars overturned and finished with.

No one said sorry, though—the messages were all merely of farewell, and of Godspeed, and good fortune for the future. Prince Charles had declined to bow to the Chinese and promptly left for his safe haven on Britannia, and as soon as was decent, and with Chinese warships watching every move (though with the frigate HMS Chatham escorting), he sailed west out of Hong Kong Harbor, bound for the Philippines, and home.

In the small hours of that postimperial night, Prince Charles wrote a diary entry, which was somehow leaked and which made it clear that he had hated every minute of the experience. “After my speech,” he wrote, “the president [of China] detached himself from the group of appalling old waxworks who accompanied him and took his place at the lectern. He then gave a kind of ‘propaganda’ speech which was loudly cheered by the bussed-in party faithful at the suitable moment in the text.” The goose stepping, said the heir to the British throne, was unnecessary and ridiculous.

The two British ships moved silently through the night and into the wind—with Hong Kong Island glittering on the port side, Kowloon and the blue remembered hills of the New Territories on the starboard. In the distance ahead were the lights of Macau, still as Portuguese a territory as it had been since the sixteenth century, but now due for its own peaceable return to China in 1999.

There comes a point, fifteen minutes into the journey, where there is a slightly awkward maneuver for any vessel outbound from Hong Kong. It occurs shortly before the steersman must begin the long and lazy turn to port that brings his ship down into the fairway and out onto the powerful Pacific swells of the South China Sea. It occurred that final June night—or was it actually July now, the pitch-dark start of a brand-new day?—when the two captains, one of the Britannia, the other of the frigate, had to make the well-known and very slight course adjustment, to avoid one well-marked obstruction, underwater.

This was the submerged wreck of the RMS Queen Elizabeth, thirty feet down and sunk there, by sabotage and fire, a quarter century before. The wreck had significance that night: the foundering of this great old British ship, the finest and grandest vessel of her time, could be said to have marked the beginning of the end for all the imperial powers in the Pacific.

But the yacht and the warship passed her by that night without remark, and then, with the sunken wreck falling fast astern, spooled up their engines to full ahead all and officially left Hong Kong and their remaining British corner of the North Pacific Ocean, forever.