January 27, 1973: The United States declares the Vietnam War over.

October 20, 1973: The Sydney Opera House is opened.

April 4, 1975: Microsoft is founded, Seattle.

NOVEMBER 11, 1975: AUSTRALIAN PRIME MINISTER GOUGH WHITLAM IS DISMISSED.

June 4, 1976: The Hawaiian canoe Hokule‘a completes her maiden voyage.

September 9, 1976: Mao Zedong dies, Beijing.

January 3, 1977: Apple Computer is founded.

. . . Australia! You are a rising child, and doubtless some day will reign a great princess in the South.

—CHARLES DARWIN, Voyage of the Beagle, 1836

Australia is a lucky country run mainly by second rate people who share its luck.

—DONALD HORNE, The Lucky Country, 1964

The moment when, on the perfect, warm spring afternoon of Armistice Day 1975, a serving Australian prime minister was suddenly sacked by a representative of the British queen, ten thousand miles away, is still known and remembered, from Perth to Sydney, from Hobart to Darwin. It is recalled simply and starkly as the Dismissal. As with Watergate, the Blitz, or the Tsunami, the economy of the description belies the enormity of the event.

It was a quite unprecedented happening, unforgettable in its staging and its consequences. It was the highest of dramas in a country long burdened by the lowest of politics. Its leading characters were petulant, pretentious, and power-hungry martinets. No one came out of it well: when the dust from the fight had cleared, there were, and deservedly so, no identifiable winners.

But it marked a turning point for Australia, by some accounts a belated coming-of-age for the only country in the world, and a very new one, that so massively occupies an entire continent. If this country of twenty-two million is now starting to play a major role in the life of the new Pacific—and it is by no means entirely certain that it has the will to do so—then this one November moment, this rather ludicrous demonstration of faraway Britain’s dwindling power over its long-ago colony, was when it all began.

The man sent packing that day was Gough Whitlam, a sleek, imposing, silver-haired and silver-tongued barrister who was seductively charming but with the temper of a honey badger. He had been Labour prime minister for three years, and his rule, which started in 1972 after a quarter century of indecorous political drift,* had sent shock waves through the Australian establishment. In his first ten days in office, he and a colleague took charge of all the government ministries (ruling as what Whitlam called his “duumvirate”), pulled the last Australian troops out of Vietnam, ended the conscription that had put them there, and freed all those imprisoned for evading the draft. He supported equal pay for men and women, increased funding for schools, and ensured land rights for the country’s aboriginals.

He gave independence to Papua New Guinea and formally opened diplomatic relations with Mao’s China, and then continued on his merry reforming way to change, and drastically, the inner workings of his country: by introducing universal health care, free university schooling, no-fault divorce laws, votes at the age of eighteen, and a set of swingeing tax reforms.

He ended the British honors system, which had long allowed the monarch in London to bestow knighthoods and medals on the citizens of a country that now delighted in its classlessness, and wanted little or nothing to do with the fiddle-faddle of nobiliary enrollment. (The system was revived in 2014.) Under Whitlam, the country also began its abandonment of the British anthem “God Save the Queen,” and eventually replaced it with, not the jaunty and traditional “Waltzing Matilda,” but the anodyne and fantastically dull “Advance Australia Fair.”

The nation, “God’s Own” as its happier residents have long thought of it, had never seen anything like it: a politician doing in government exactly what he had pledged to do during his campaign, and doing it fast—“crash through or crash” was Whitlam’s mantra—and overturning Australia’s social status quo in a matter of weeks. His popularity among the no-nonsense armies of Australia’s working “blokes,” and many of their spouses, soared. He was for a short while widely regarded as the best prime minister the country had ever had,

But only for a short while. All his achievements, so many of them won at enormous cost to the taxpayer, helped to concoct a formula that was ready-made for political disaster. And given that so many popular politicians unwittingly flirt with hubris, the disaster was not long in coming. It had much to do, as ultimately the whole scandal had, with money.

It was one specific spending scheme that triggered his government’s spectacular fall.

Late in 1974, in the aftermath of the worldwide oil shock and its associated economic turmoil, Whitlam launched an attempt to insulate Australia from any such energy-related problems in the future by boosting the country’s immense and untapped supplies of energy. Specifically, it needed to create a number of large new mines to extract coal and other of the many minerals with which Australia had been blessed, to build a giant new gas pipeline, and to electrify a long series of freight railways in the country’s southeast. Constructing all these would cost the then-staggering sum of four billion dollars, an amount of proposed spending very much in keeping with the Whitlam government’s reputation for profligacy on a heroic scale.

The energy minister, a financially unsophisticated former used-car salesman, heard rumors at a late-night cocktail party that a Pakistani trader in London could lend such a sum, denominated in then freely available petrodollars. Moreover, the trader could lend the money at knockdown interest rates, an arrangement that could be secured simply in exchange for paying the trader a $100 million commission.

Such a plan seemed to the minister not only convenient, but also just—in that by doing the deal, the impoverished West (as Australia regarded itself) could now get back some of those dollars it had given to OPEC and assorted other oil-trading villains who had conspired in the decade’s savage oil price increases, and which had wreaked so much damage worldwide. The minister didn’t smell a rat; nor did he ever imagine that the trader might be a less-than-honorable man, though he had been given advice from London that the trader was, if not necessarily a crook, then at least deeply unreliable. So secret negotiations got under way.

Inevitably, with the Australian press being tireless in pursuit of malfeasance, news of these secret talks broke open, and Whitlam’s political opposition scented blood. A Melbourne newspaper produced telexes showing that the car salesman–minister had lied to Parliament about the talks, and though he was promptly fired for doing so, the opposition (a coalition of anti-Whitlam parties led by a smooth, Oxford-educated up-and-coming politician named Malcolm Fraser, and which narrowly controlled the Australian Senate) forced Whitlam into a corner. They pressed home their advantage with a simple threat: Whitlam must call a general election, which by now he would be likely to lose; and if he didn’t, the Senate would refuse to authorize any further money for the running of the government.

Whitlam, stubborn and proud, refused to give way. Accordingly, Fraser did as threatened, called his parliamentary colleagues to order, and cut off the government’s money. It was a simple, if devastating, crisis. And because of the uniquely British manner in which the Australian government was run, its sole possible solution was a uniquely British one. The queen had to become involved. No matter that she sat on a throne halfway around the planet. She now had a constitutional role to play, and given Whitlam’s intransigence, she was obliged to do so.

Not the queen herself, however. Her Majesty had a local representative. He was a former boilermaker’s son from Sydney named John Kerr, a cherubic but leonine figure who had worked his way up through the Australian education system to become one of the country’s prominent labor lawyers. To add irony to this particular situation, he had been appointed to be the queen’s man in Australia, the governor-general, by none other than the politician who was now at the center of this imbroglio, Gough Whitlam.

The office of governor-general—a figure who in Australia is splendidly uniformed and copiously bemedaled, and has a flag of his own, an emblem of his own, a fleet of large cars without license plates, a flotilla of boats, the use of a private aircraft, and servants staffing a pair of fine and opulently furnished houses—is one peculiar to the collegial and world-girdling body known as the British Commonwealth. All the countries with a governor-general today are former British territories that have chosen to retain the British monarch as head of state. In other words, they have opted not to become republics, with presidents of their own, heads of state who are homegrown and homemade. And the Pacific, as an earlier chapter has demonstrated, is amply supplied with such former British possessions: notably Australia, Canada, Fiji, Hong Kong, Kiribati, Nauru, New Zealand, the Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu, and Vanuatu. Only four of these, however (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the Solomon Islands), still recognize the queen of England as head of state. So only these have governors-general as Her Distant Majesty’s local representatives.

And only one of these, the eighteenth governor-general of Australia—who in full was in 1975 titled “His Excellency the Right Honourable Sir John Robert Kerr, AK, GCMG,* GCVO, QC, of Government House, Canberra and Admiralty House, Sydney”—ever had the temerity to wield the ultimate reserved power of his office. And he shocked the world by doing so.

In normal circumstances an Australian governor-general—usually a white man, until 1965 wellborn and British, only once a woman (named Quentin), and thus far not even once an aboriginal—does little more than put on fancy clothing and wander about opening things. Technically he is the country’s head of state, so he receives foreign ambassadors, represents the country on overseas excursions, and is the commander in chief of the armed forces.

Yet, technically, while he is the representative of the British monarch, and is bound to perform the monarch’s wishes, he also wields some power of his own, as an Australian. And this power can be considerable. In particular he has what are known as reserve powers, one of which is the ability, under certain constitutionally defined circumstances, to sack a serving prime minister.

Which is what Sir John Kerr did—and to the very man who had appointed him. He put the boot in shortly after lunch on Tuesday, November 11, 1975.

This would have been a busy day in ordinary circumstances: it was the day when Angola, on the far side of the world, became independent from Portugal; the day when Australia marked the anniversary of the 1880 hanging of its most notoriously romantic criminal, the armor-wearing Ned Kelly; and the day when millions would stand in silence to remember the dead of various world wars, the eleventh day of the eleventh month having been chosen to mark the memorial of all.

But for this singular Australian crisis, the date remains seared into the soul of every Australian living at the time. For no one imagined this would or could ever happen.

Whitlam and Fraser had been sparring in complicated and deviously political ways for several days. On that Tuesday morning, Whitlam insisted that if no money was forthcoming, he would, in fact and at last, call an election. He telephoned Kerr to make a formal appointment to come and tell him so. Kerr, however, decided to act preemptively on his own—being only too aware that Whitlam might well telephone Buckingham Palace and have the queen remove him, Kerr, from his job, as Whitlam had every right to do. So, in his view, he had no alternative but to remove Whitlam from his job first, before Whitlam could possibly move against him. He accordingly telephoned Fraser in his capacity as leader of the opposition, and told him to report to Government House (the governor-general’s official house), clandestinely but immediately. It was all memorably Machiavellian.

So Fraser was already there, carefully hidden away in an outer room, when Gough Whitlam, fifteen minutes late and quite unsuspecting, arrived for his own appointment. He was shown into Kerr’s official study, saying he had the documents for signature calling for the long-awaited election. Kerr said that before he would look at those documents—which in any case he could not sign because an election could not be held until the money supply was restarted—would Whitlam kindly read the letter he now handed him. Whitlam sat back and read the four-paragraph document, with mounting astonishment.

“Dear Mr. Whitlam . . . In accordance with Section 64 of the Constitution,” it began, and with much highfalutin quasi-colonial rigmarole went on to authorize the “dismissal of you and your ministerial colleagues . . . great deal of regret . . .” and ended, with magisterial defiance: “I propose to send for the Leader of the Opposition and commission him to form a new caretaker government, until an election can be held.”

Such a thing had never happened before in Australian politics, and in modern times, seldom before anywhere. It was the modern version of the ax and the block: sudden, swift, and dramatic.

So there was much spluttering. Whitlam first tried to telephone Buckingham Palace, to demand that, instead, Kerr be sacked. But it was 2:00 a.m. in London, and no one answered the phone. Whitlam left Government House shaking with rage. Fraser, waiting sheepishly in an anteroom, was then ushered into Kerr’s office and told that, provided he untied the cords of his reticule and permitted the flow of money to resume, he would now be Australia’s prime minister. He agreed, wrote and signed a letter, and was formally sworn in just after lunchtime that very day.

Word leaked out within moments. Radio stations broke into their regular programs. Crowds began to gather. Fraser, it was widely assumed, had played a dark game, and stones were thrown through the windows of his political party headquarters in Melbourne. Dockworkers immediately went on strike, and all the country’s ports were promptly closed to foreign trade. Australia briefly shut itself down. People spoke of a coup d’état. Whitlam put out an inflammatory statement, urging his supporters to “maintain your rage.” The capital, Canberra, was in an uproar, and in a flurry of frantic activity, votes were being called, statements were being made; the House of Representatives refused to accept Fraser’s elevation, and then refused to adjourn itself; and it was only when the Senate accepted the transfer of power and passed the money supply bills to get the nation under way once more that some sort of legislative calm settled on the nation.

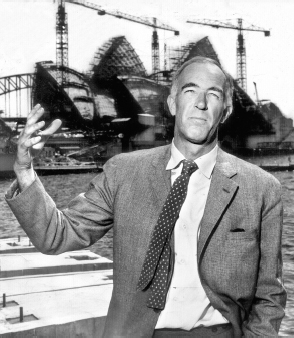

The silver-haired lawyer-politician Gough Whitlam at the moment of his dismissal as Australia’s prime minister at the hands of the Queen’s local representative. The event proved a watershed in the governance of this former British possession.

National Library of Australia.

The drama’s final act played out on the steps of Parliament, with a bemused Whitlam, jostled by scores of heavily sideburned reporters (this being the mid-seventies; no doubt their trousers were flared), listening to an icy, unsmiling civil servant, David Smith, who had been deputed to read out the governor-general’s formal proclamation. Whitlam, with his swept-back mane of silver hair, stood tall, cutting a praetorian figure. When finally Smith ended his peroration with “God save the queen,” Whitlam drew himself up still more majestically and rumbled famously into the microphones, “Well may we say, ‘God save the queen,’ because nothing will save the governor-general.”

This was followed by disturbances and marches and protests of one kind and another—“We Want Gough!”—for several days to come. But the deed was done. When the election was held the next month, Fraser won the country by a thumping majority, the largest in the country’s history thus far, and he ruled through three further elections, until 1983.

Though Whitlam had once called Malcolm Fraser “Kerr’s cur,” the pair became firm friends in the aftermath of the affair, and when Whitlam died in 2014 (just a few months before Fraser himself died, in 2015) his successor had the kindest of words to say of him. Whitlam, indeed, was viewed as an elder statesman, a man whose three years of policies had changed Australia for all time. “He had the sense of Australian identity,” said Fraser. “He had the vision for an independent Australia. He had a grand idea for the country.”

Other former prime ministers agreed. “A true internationalist and regionalist,” said one of them, Bob Hawke. “He helped Australia earn the world’s respect,” said Paul Keating, another. “The country came very close to the same marginalization that South Africa experienced over racial discrimination—our salvation from that occurred through and with Gough Whitlam.”

And most agreed that the Dismissal eventually achieved the opposite of what John Kerr had intended, which was to remind the country that he, the queen’s man, still wielded in extremis, and on her behalf, the ultimate authority over her faraway dominion. For the office of Australian prime minister has since become hugely enhanced, London’s authority has dwindled to little more than a vague notion, Canberra’s power as a federal capital has been greatly magnified,* and the endless disputes among the country’s various states and territories have been generally reduced to a dull roar.

Coincident with this affair, Australia’s presence in the Pacific, and as a regional power, has become steadily more visible. The Australians’ vocal determination that no such thing as the Dismissal should ever happen again appears to have triggered a sense of national resolve, an empowerment that has advanced the country and its standing in the world no end.

The luckless John Kerr himself was to be the butt of hostility and acrimony for the rest of his days. At almost every occasion, when he was asked to cut a ribbon or lay a foundation stone, he was mobbed by demonstrators or subjected to a withering barrage of catcalls. He took first to drink, and then he took to London, and he ended his days miserably, staggering and disdained. When he died in 1991, his family buried him quietly and in secret, sparing the government of the day—by now Labour once again, just as Gough Whitlam’s government had been in 1975—from having to contemplate a state funeral. It almost certainly would have denied such an honor to one of the most despised men in recent Australian history.

If the crisis of 1975 provides a convenient marker year for Australia and for its standing as a Pacific regional power, then there was something else about the mid-seventies, something less specific, less amenable to definition, but nonetheless wholly recognizable. For the time can perhaps also, if very roughly, be said to have ushered in a sense of a quite new Australian style, a phenomenon that promptly (and at last!) lent a touch of swagger to the country’s newfound authority.

Even Australia’s most ardent admirers would probably admit that style was a commodity not much in evidence in the country’s immediate postwar years. This, after all, was a nation that for decades had displayed cultural cringe prominently on its sun-bronzed forearm, and seemed to wish to bask in intellectual underachievement and a mulish incapacity for any kind of distinction, except in matters relating to sport. The reputation that Australians had then was one born of a gallimaufry of clichés: of meat pies; of grubby pubs; of kangaroo hunters, perpetual sunburn, the outback, larrikins, a brutish kind of football, poisonous spiders in the dunny, Anzac biscuits, Vegemite and lamingtons, Castlemaine XXXX, the tall poppy syndrome, blackfellas, barbies, “G’day, sport,” an enviable competence at cricket, an enviable concept known as mateship, the White Australia Policy . . .

Yet if anyone dared be critical of such things, or cringed at their existence, then all and any of the ill will such as these provoked would be quite trumped by one other singular and undeniable fact: the Aussies’ singular courage and determination in war, and the simple sad affection of their countrymen and -women who sent them off to fight. At Gallipoli the no-nonsense nature of the memorials to the eight thousand Australians who fell to the Turkish machine guns make this point with a special eloquence. A passerby will find, instead of grand marble graves tricked out in gold, small cards leaning by more modest tombstones, many a one left there by a mother, or else by friends who came when the mothers couldn’t afford the fare. “You did your best, son,” the cards say, or something like it. Or else there are notes placed by their mates, who had come from back home: “Good on Yer, Billy-boy,” or “You done good, Jack.”

A kindhearted country, a visitor would be likely to say—on visiting both the country and, more decidedly, the country’s faraway memorials. A goodhearted, kindly people. And if with not too much style about them, then so be it.

But come the mid-1970s, a new affect began, if timidly at first, to edge out the old. Australia started to present itself in a quite different manner. Within just a few months of each other in 1974 there appeared two markers of note: one that served to remind outsiders, if only satirically, of the adherent nature of the old Australian ways; and the other that, in a far more substantial manner and not satirically at all, delightedly and majestically exalted the new.

The first—and it has to be stressed that this is satire writ large—was the unanticipated appearance on the world scene of an antipodean archetype: the entirely memorable Australian diplomat named Sir Leslie Colin Patterson—Les Patterson, as he would genially remind his audiences, for short.

I first encountered Sir Les in Hong Kong in the autumn of 1974, when he made a speech in the swanky comfort of the Mandarin Hotel, formally announcing his appointment as Australia’s cultural attaché to the Far East. He had been officially sent out from Canberra “to impugn,” as one commentator had it, “the fundamental refinement of the Australian character.” He was just thirty-two years old, with a career already hinting at greatness.

Thanks to family connections from his schooldays in Taren Point, in the southern Sydney suburbs, he had been plucked out of a soul-destroying job in the Literature Division of Her Majesty’s Customs and Excise Office, and given the portfolio of “shark conservation minister” in the government of Sir Robert Menzies. He adroitly managed to survive the change to Gough Whitlam’s Labour government and became “minister of drought.” Next came his appointment as a cultural attaché, from which he would go on, two years later, to be posted in this capacity in London, then recalled to be chairman of the Australian Cheese Board, to become founder of a private school of etiquette, and later to be given the title of “adviser on etiquette and protocol” to the Australian federal government.

Sir Les’s sense of vision was evident even during his youthful first appearance in Hong Kong. That evening, if I remember correctly, he wore a vividly iridescent blue suit, with a yellow check lining, which had clearly seen many better days. His tie, the wide style of which owed much to cinema noir films of the 1940s, bore encrusted evidence of his many earlier dining experiences. His teeth were long, and they protruded, and they were stained the same coppery color as his fingers, which seemed always to be clutching a cigarette from which dangled an ash of improbable length. His hair, long and amply greased, hung over the none-too-well-laundered collar. One of his shoes was missing a lace.

He appeared that evening to have had a fair amount to drink and needed some support from diplomat colleagues when attempting to stand. He was easily tempted into making remarks about human reproductive activities, and made it clear he was not in favor of men lying with men. However, he had no particular problem with women lying with women, since he could not entirely understand what they did when they lay together, and no one in his various Roman Catholic schools back in Taren Point had ever found the time to explain it to him.

He was by all appearances overfed; was often overcome with what appeared to be libation-triggered tiredness and emotional excess; and to judge from his utterances, was evidently wildly oversexed. His outbursts caused many of his more sensitive listeners to recoil. His favorite nonsexual pastime, which he often indulged in while giving the very speeches that so marked his career, seemed to be either nasal excavation and gastronomy or competitive wind breaking. He was a caricature, in short, of a certain kind of Australian of old, an amalgam of bronzed ocker and working stiff, of corrupt pol* and journeyman sheep stealer. I daresay some, even in the eighties and nineties, when he was most visibly on the world speaking circuit, imagined that he did represent some kind of an Australia that still existed, if only just.

Les Patterson was, of course, entirely fictional—a character created by the writer, comedian, and artist Barry Humphries, whose other alter ego is the somewhat more lovable and acceptable Dame Edna Everage. It would be idle to read too much into what is essentially and only a fictive creation of contemporary comedy. Yet Sir Les Patterson, who performed for more than thirty years after his creation, well into the twenty-first century, is still quite recognizably emblematic of an Australian type—a type that most modern Australians hope is fading in the rearview mirror as the country eases itself steadfastly into the more respectable and respected role that it increasingly likes to play today.

A role that owes much to, and is symbolized by, the creation of one quite remarkable building, and one that happened to be completed at almost exactly the same time that Sir Les Patterson first made it onto the stage. This structure is the Sydney Opera House, and it was formally opened in October 1973 by Queen Elizabeth, in her role as queen of Australia. The American architect Frank Gehry once said it was a building that, quite simply, “changed the image of an entire country.”

Until that moment, Australia did not possess one national construction that the world would see and instantly mouth, “Australia!” There was of course the immense sandstone upwelling of Ayers Rock, Uluru, which spoke of outback, of remoteness, of the aboriginal peoples and the continent’s serene inner space. But other nations that had natural wonders on a similar scale had man-made marvels, too. America had its Grand Canyon and its Empire State Building. Britain had both its White Cliffs of Dover and Stonehenge. Egypt had the Nile and its Pyramids. Australia did not.

The best that Australia could muster, and which might be seen to complement its own natural wonders, was the great “Coat Hanger Bridge” that spanned the narrow entrance to Sydney Harbour. But it wasn’t really Australian: the Sydney Harbour Bridge was more properly a monument to empire, since it was constructed by a firm in Middlesbrough, and made mostly of steel that had been shipped down from England. To regard that as an Australian monument might be akin to a Delhi resident showing off the Viceroy’s House by Edward Lutyens, instead of the Taj Mahal.

But to see the Sydney Opera House—and yes, framed by the now venerable bridge, for together the two offer a quite incomparable spectacle—and to see its jumble of graceful white sails, its soaring peaked seashells all apparently floating beside the blue ship-busy harbor waters, is to experience the sublime lyricism of one of architecture’s greatest moments. You see it when you fly in to Sydney, you see it when you drive beside the harbor, you glimpse it peeking between the skyscrapers of the business district. And each time you see it, you notice it. It is a building impossible to take for granted. It is a masterpiece.

One recent sighting rekindled a bittersweet memory. Just after dawn one summer’s day in Sydney, I was telephoned from a hospital in New York. Would I speak, the caller asked, some last words to a dear friend of mine, an elderly editor beloved around the world, and who now was dying in a room surrounded by friends. He was unconscious; his breath was labored. But they put the telephone to his ear, and I described to him as best I could what I could see from my hotel window: the sun gilding the top of the great bridge, the little insect-like Manly ferries skittering along on white-waked water, bringing commuters across the bay, and then, rising from between the office towers like a clutch of lilies, the soft peaks and angles in a sun-washed pink of the Opera House.

When they took the phone from his ear, they told me his breathing had paused. They were sure he was listening to every word, for he loved Sydney as I loved it, and my sending him a farewell from there brought him serenity, if only for a moment. He died an hour later, calm and at peace.

But there was little peace in the making of the Opera House—and the saga of its construction amply displays many of the same contradictions evident in the makings of today’s very new Australia. The dramas of the years of its building (together with one terrible, coincident tragedy and another subsequent sex scandal) were legion: there were vicious tugs-of-war between forces old and new, between provincialism and globalism, between old-school philistine Australia and twentieth-century visionary Australia. The battles spoke volumes about the process; yet the result is memorable and wonderful, and could not have been made, it often seems, anywhere else in the world

All began peaceably enough. It was an Englishman who first conceived the need for a dedicated opera house in the country’s cultural capital: the conductor Eugene Goossens, the London-born scion of a distinguished Belgian musical family, who had been invited to Australia in 1947 after a highly successful two decades in America, to conduct the Sydney Symphony. But not long after he arrived he was heard grumbling that his new orchestra’s home, the ornate Victorian town hall, even though it had one of the world’s largest pipe organs, was far too small. Sydney, he insisted, deserved better. It could be a world-class city; it should have a world-class opera house.

His six years of energetic lobbying eventually bore fruit in 1954, when the then–New South Wales premier, a former railway worker and insurance salesman named Joe Cahill, threw his weight behind Goossens’s idea. He agreed to clear space for an opera house by demolishing a city-owned tram depot on a delightful little peninsula, Bennelong Point, just north of the city’s beautiful Botanic Gardens. Cahill staged an international contest to find the best architect: more than 230 men and women from more than thirty countries submitted drawings. It seemed as though the entire architectural world wanted Sydney, so spectacular a city in so visually blessed a country, to have something special.

The winner was an almost unknown architect from Denmark, a forty-year-old would-be sailor and admirer of Mayan temples, a man with not a single memorable building yet constructed, named Jørn Utzon.

The story goes that Utzon’s vaguely realized sketch, all elliptical shells and curves that seemed to burst organically upward and outward into the harbor like spinnaker sails, or like a huge billowing flower, was initially rejected—but that Eero Saarinen, the Finnish jury member already known for his futuristic designs in the American Midwest, pulled Utzon’s sketch from the reject pile, declared it a work of total genius, and said he would support no other competitor. “So many opera houses look like boots,” he said, a little oddly. “Utzon has solved the problem.” The Sydney city assessors, who had the final vote, were equally enthusiastic: “We are convinced that they present a concept of an Opera House which is capable of becoming one of the great buildings of the world.”

Utzon was sent a telegram informing him of his success. His ten-year-old daughter, Lin, intercepted it and brought him the news, pedaling her bicycle furiously across the flat Danish countryside to his studio, and then demanding, “Now, can I have my horse?” He could well afford it: Sydney wired him the prize money of five thousand pounds* and told to come on down and get weaving.

The weaving, though, proved to be something of a trial. Like so many of architecture’s stars—Gehry, Calatrava, and Frank Lloyd Wright come to mind—Utzon was big on vision, short on details. For example, he was never quite certain that it was possible to make the ogival shells for the roofs—especially because of their different sizes, with varying arcs and angles. The cost of all the eccentrically shaped wooden forms that would be needed to support the drying concrete for each one was going to blow a massive hole in the budget. Moreover, the total weight of these extraordinary roofs exceeded the strength of the concrete pillars that were to support them—a potentially lethal problem for audiences, a death knell for the building.

As the costs mounted, the project slipped behind, and the state government organized an emergency lottery—first prize, one hundred thousand pounds—to help raise further funds. Morale was helped in 1960 by the impromptu appearance on-site of the American singer Paul Robeson, who gave an unexpected concert among the cranes and scaffolding towers. He sang “Ol’ Man River” to a throng of Italian and Greek construction men, his dark face and their olive complexions prefiguring Australia’s future of multiculturalism.

Then, in 1961, the design teams came up with the technical breakthrough, the aha! moment, that finally made Utzon’s dream possible. All the shells, the technicians declared, could be thought of as parts of a single enormous sphere, like segments of an orange. Since they would all now have a common radius, they all could be cast from a common mold, and then cut down to smaller sizes in those places where Utzon wanted them. It seems such an obvious solution now, but in 1961 it took hundreds of computer hours (when computers were rarely used to solve architectural problems) to come up with the final answer to a taxing technical conundrum. There has been some controversy over whether it was Utzon himself or some other mathematically inspired architect who enjoyed the necessary epiphany. But in either case, the project was then promptly freed to race toward completion.

Jørn Utzon, the unassuming Danish architect plucked from obscurity to design Australia’s best-known structure, the Sydney Opera House, never saw it opened, but was honored posthumously for the creation of one of the world’s greatest public buildings.

Newspix/Getty Images.

Or it should have been—but then the old Australia briefly reared its head. In 1965 a new state government took office, with the Opera House still a long way from being finished. Two of its most senior figures happened to be politicians who, in terms of their deep disdain for high art and culture, could give Les Patterson a run for his money. They were the new leader, Bob Askin; and, more notoriously, his public works minister, Davis Hughes, a figure described by the Australian critic Elizabeth Farrelly, in Utzon’s obituary, as “a fraud and a philistine,” a man who falsely claimed to have a university degree and who had “no interest in art, architecture or aesthetics.”

Hughes wanted Utzon out, denouncing the architect as a foreigner, a prima donna, and in the very worst sense of the word, an artist. Using the want of taxpayer money as the excuse, the minister gradually pared down the budget, slicing away at the architect’s ability to pay his bills or, indeed, his staff. “How can you alter everything against my advice?” Utzon bleated pathetically during one meeting. “Here in Australia,” Hughes responded tartly, “you do what your client says”—the voting people of New South Wales, of course, being collectively the client.

Day by day through the southern summer of 1966, Utzon’s situation worsened; and when, in February, he totted up the figures to show that the government owed him some one hundred thousand dollars* in fees, and threatened to resign, Davis Hughes called his bluff and accepted.

Utzon, shattered, left Australia six weeks later, traveling under an assumed name to avoid the press. A thousand protesters marched to the half-completed building, many of them architects. A local sculptor went on hunger strike to demand that the Dane be invited back. And though he expected to be recalled, he never was.

Instead, several Australian architects were hired in his place, and they took seven further years to complete the building’s initially drab and uninspiring interior. While the outside sailed itself into architectural history as one of the great creations of the twentieth century, the inside was riddled with imperfections and crabbed spaces—early operatic orchestras had to have their percussion sections cordoned off behind plastic screens so the violins could hear themselves; ballet dancers exiting the stage had to have catchers stationed in the wings to stop them from hurling themselves into the walls.

Jørn Utzon never came back to Australia, and he never saw the completed Opera House in person. When the queen opened the building in October 1973, twenty years after it was first conceived, ten years later than scheduled, and 1,400 percent over its original budget, Utzon was not invited; nor was his name mentioned. Publicly, he was an unperson; privately, he remained stoic and unembittered. His most sardonic comment was simply to call his experiences in Australia an example of “Malice in Blunderland.”

And he continued to believe that history would eventually judge him more kindly. His faith would be borne out in his later years, when Australia effectively apologized to him. He was given an award, the Companion of the Order of Australia, in 1985. But then, more important, he was given work. The inadequacies of his building’s interior were deemed so egregious that, in 2000, Utzon was approached to help undo the botches of the Sydney architects, and to redesign it. He said he was minded to accept the commission—though on hearing him say so, a clutch of guardians of the old Australia briefly stirred themselves to life once more. The ever-querulous Davis Hughes, for instance, swiftly went to the papers: “There’s obviously a need to upgrade the place,” he allowed, “but why do we need Utzon? Why can’t we get a competent Sydney architect?”

Yet, in the end, the Dane did do the work, though from long distance, by airmail and couriered blueprint. The city was so duly delighted with the result that the Utzon Room (light, airy, sparely furnished, and with views of the sparkling harbor below) was named in his honor. The old man, now unwell and living in Mallorca, was thrilled beyond measure to receive the news, and reacted with undeserved magnanimity. “The fact that I’m mentioned in such a marvelous way, it gives me the greatest pleasure and satisfaction. I don’t think you can give me more joy as the architect. It supersedes any medal of any kind that I could get and have got.”

The queen came back once again, in 2006, to open the refurbished interiors that Utzon had designed. Utzon himself was by now too ill to travel so far, but his son was there, and he made a wistful speech in which he said that his father “lives and breathes the Opera House, and as its creator just has to close his eyes to see it.”

Utzon died in Copenhagen two years later. A year after his passing, the city of Sydney staged a concert, as both memorial and official reconciliation. An apology, if you will. But the event paled before the world’s recognition of what he had accomplished. Shortly before he died, Utzon heard that UNESCO had declared his creation a World Heritage Site. The proclamation was lengthy, as befits a structure of such complex design and tortured history. Its preamble was eloquent: Jørn Utzon’s building, a gift from Europe to the Pacific, and thence from the Pacific to the world, was “a masterpiece . . . its significance is based on its unparalleled design and construction; its exceptional engineering achievements and technological innovation and its position as a world-famous icon of architecture. It is a daring and visionary experiment that has had an enduring influence on the emergent architecture of the late 20th century.”

As befits so troubled a passage to completion, there were two codas to the Opera House story, both of them melancholy—one quite tragically so, the other more curious and bizarre.

The first related to the lottery, which had been staged in 1960 to raise additional funds for a project whose costs were at the time beginning to spiral beyond control. The prize offered was one hundred thousand pounds; and on June 1, the winner’s name was announced in the newspapers: a Mr. Bazil Thorne, who lived with his family in Bondi, where the surf famously pounds in from the South Pacific Ocean. There were no privacy laws at the time; the family’s full address was listed in the paper.

A week later, the Thornes’ eight-year-old son, Graeme, was picked up at a street corner near his home, to be taken to school—only, he never arrived. That night a man called the house demanding twenty-five thousand pounds in ransom. A massive police search began, ending a wretched month later when the child was found bludgeoned and suffocated.

The killer was captured three months later, after a triumph of forensic detection that involved pink paint chips, mismatching flower types, stolen cars—and the discovery that the man allegedly involved had just left Australia aboard a London-bound P&O passenger ship, the SS Himalaya. Australian federal police were waiting for the vessel when she arrived in Colombo; and after much legal complication (since the Sri Lankans did not at the time have an extradition treaty with Australia), the man, a Hungarian immigrant named Stephen Bradley, was arrested and returned to his adopted country. Aboard the plane, he confessed to the child’s murder. He was sentenced to life imprisonment, and died in his cell eight years later.

The other coda is more simply bizarre, and involved a train of events that provide their own commentary on the fifties Australian zeitgeist. For Sir Eugene Goossens, the towering and talented figure of English music* who, while conductor of the Sydney Symphony, had begun the process that led to the building of the Opera House, turned out to be a man of highly exotic sexual tastes. And that, to the Australia of the time, was most decidedly not on.

While in Sydney, Goossens became romantically involved with a woman named Rosaleen Norton, who was a pagan, a keen practitioner of the occult, and a lady who had a liking for both flogging and unusual kinds of misbehavior with animals, mostly goats. The popular press in Sydney—then, as now, eager for London-style sensation—liked to call Miss Norton the Witch of King’s Cross, and her studio and place of work were very much a cornerstone (a socially unacceptable cornerstone) of this louche and seedy Sydney neighborhood.

Goossens, who himself was an admirer of the British occultist (and would-be climber of Kanchenjunga) Aleister Crowley, would occasionally bring Miss Norton gifts from London. In March 1956, after he had returned from being awarded a knighthood at Buckingham Palace, customs rummagers at Sydney airport found in Goossens’s suitcase large numbers of dubious photographs, together with rolls of film and what were described as “ritual masks.” He was promptly arrested, and threatened with the serious charge of “scandalous conduct.” He was not unreasonably terrified by the prospect of spending a lengthy time in prison, and eventually agreed that he had violated a section of the Customs Act that banned the import of “blasphemous, indecent or obscene works” into Australia. His crime carried the lesser penalty of a fine, and he eventually was obliged to pay up the not insubstantial sum of one hundred pounds.

But what he didn’t reckon on was the publicity, which was immediate and merciless. The event, and its prominence in the more raffish newspapers, brought to an abrupt end what had been a glittering musical career. Goossens, now utterly shamed in public, immediately resigned from both the symphony and the New South Wales State Conservatorium, and fled to London on his sixty-third birthday. Just as Jørn Utzon would do ten years later, Goossens chose to slink out of the country under a pseudonym and in disgrace. He was subsequently described by friends back in England as having been “absolutely destroyed” by the affair. He was dead six years later.

Yet, as with Jørn Utzon and the room now dedicated to his memory, there would in time be a more kindly end to Goossens’s story, too. The Opera House, the grand realization of his long-ago vision, was opened ten years after his death. And when it opened, the foyer held a commanding sculpture of the conductor, honoring the contribution that he had made to the building of one of the great monuments to music in the twentieth century.

One television journalist in Sydney later wrote that Goossens had surely been a victim of the times, of what she called the wowserish,* churchly, prudish, censorious, hypocritical, and deeply conservative Australia. His offenses were, by today’s standards, entirely venial, unworthy of remark. Though the law that Goossens broke remains, technically, on the books, no case has been brought under its strictures for many decades. The Australia of those times, one can be certain, has now been all but submerged, almost forgotten. On the surface at least, Australia is a liberal and tolerant society, multicultural in nature and cosmopolitan in attitude, its politics progressive and forward-looking, and with a reputation and a standing that in consequence have changed in the past half century almost beyond recognition.

Or have they changed? Few would dispute that if Australia ever wants to enjoy a degree of respect in the western Pacific commensurate with its wealth and power, it has to be taken seriously by its neighbors. Most especially by its Asian neighbors, those who inhabit a vast slew of north-running countries from New Guinea up to Siberia, by way of Indonesia and Indochina, the Philippines, Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and mainland China itself. For many years, that had not been the case at all: Australia was regarded principally as a source of minerals, little more than an immense quarry, and was much caricatured as such, as an uncultured, socially conservative, unsympathetic, misogynistic, and racist outpost of the British Empire.

Geographically and geologically, and with its own distinct and ancient native anthropology, Australia is properly and undeniably a component of Asia. Yet in societal terms, and as reflected in its press and by way of its politicians until as recently as the 1970s, it seemed to see itself differently—not as part of the East at all, having made no serious attempt ever to be so, and with the great majority of its people shuddering at the thought of ever becoming so.

It was the country’s infamous White Australia immigration policy that first set the tone. Laws were enacted in 1901, from the country’s very beginnings as an independent federation, to protect it from Asians, “from the coloured races which surround us, and which are inclined to invade our shores.” The whites-only policy was declared by its supporters to be the nation’s Magna Carta, the ultimate shield that would prevent the country from being “engulfed in an Asian tidal wave.”

This was motivated by fear, of course. It was much the same fear as was enacted on the American side of the Pacific, and that hastened the passage of the various exclusion acts that kept “Orientals” so firmly at bay in California and beyond. Fear of the Chinese among Australian miners who couldn’t dig as fast or as furiously. Fear of the Pacific Islanders who would work in the cane fields of Queensland for much lower pay than their white counterparts. Fear of the Filipinas who might launder the linens and cook the pork stews with more alacrity and eagerness than would the ladies from Ireland and South Wales. Fear of the Indians and Malays who could labor on the stations of the outback with far less complaint about the heat than the wild but pale-skinned Australian boys whose ancestors had emigrated from English cities such as London, Leeds, and Liverpool.

Wars with the Japanese hardly helped. The original act that had been passed after the First World War was to be hailed by successive immigration ministers as “the greatest thing we have ever achieved,” and in keeping out nonwhites (Japanese now most especially), it seemed an even more blessed creation at the start of the Second. The prime minister of the day backed the policy wholeheartedly: “This country shall remain forever,” he declaimed, “the home of the descendants of those people who came here in peace in order to establish in the South Seas an outpost of the British race.”

The Labour Party, purportedly the champion of the working man, turned out to be the most vocal in keeping Australia as pure as pure could be. “Two Wongs don’t make a White,” said a Labour Party immigration minister in 1947. Under the strictly enforced rules, no madmen could come in, no one afflicted by an illness “of loathsome or dangerous character,” no prostitutes, no criminals; nor could any “Asiatics” or any “coloureds” enter, either; and for good measure, no one who failed a written dictation test, an examination that could be given to an unwary applicant at a moment’s notice, and in the language (not necessarily English) of the immigration officer’s spontaneous choice. Sometimes the officer would, for his own amusement, choose to have his applicant write out the test in Gaelic, to be quite certain of a ban.

This couldn’t last, of course, this fantastic notion of keeping Australia an antipodean refuge for snow-white Britons, for simon-pure Englishmen. Soon after the end of the Second World War, when war brides began knocking at the country’s doors, they were opened a crack, and somewhat reluctantly, to some of the swarthier-looking Europeans: Greeks and Italians at first. They soon came in waves, found the climate and the scenery and the city life much to their liking, and were publicly welcomed in return to a far greater degree than the politicians had supposed. Melbourne in particular soon became the most populous Greek city outside Greece. And these immigrants were well liked. “Better a dark-skinned Greek than a Japanese,” one historian commented.

Then, in the 1960s, the Japanese and the Chinese started being allowed in, too—“distinguished and highly qualified Asians” only, at first; then, as these bellwether arrivals were found acceptable, the restrictions were eased still further. Before long, members of the Oriental races who were vaguely described as “well-qualified” could apply to enter, too. And then, by 1973, Gough Whitlam, as part of his abruptly instituted reform program, ended all such restrictions. The dictation test had already been scrapped. The degrees of qualification were now dropped. The question of an applicant’s race vanished from the forms.

All who now wanted to come, and who met the none-too-strict criteria of entry, were welcome to apply. The seventy-year-old White Australia policy was swept into history. The country now became, and in short order, a great multicultural experiment. A country first manufactured as the colony of interloping white men could now reinvent itself as a brand-new community born of the entire world. It was a locally novel type of national entity, a western Pacific version of two tried-and-tested equivalents—Canada and the United States—on the ocean’s faraway east coast. All three experiments were at last joined to an ocean that was now fast turning itself into a test bed, a place where the future of human society would begin to be charted. The U.S. president Bill Clinton seemed to understand this when he came to Sydney in 1996: “I cannot think of a better place in the entire world, a more shining example of how people can come together as one nation and one community.”

It was quite an endorsement. Except that inside Australia, there were still legions of highly vocal opponents of any policies like this, policies that might draw the country more closely, as they saw it, into Asia’s too foreign maw. Some of the shriller of these have adamantly refused to quiet themselves, to accept the realities of change. They have on occasion managed to tap into an alarming groundswell of very ugly popular opinion, and by doing so have managed to set back somewhat Australia’s gathering reputation as a fully functioning member of a new pan-Pacific society.

Pauline Hanson is perhaps the most egregious recent example. This was a lady who came to brief prominence in the autumn of 1996, on the heels of a savage outbreak of race rioting that briefly convulsed the country. She was a twice-divorced mother of four, of very limited education, and the owner of a fish-and-chip shop near Brisbane—who yet managed to win election to the federal parliament in Canberra on a platform of undiluted racism and xenophobia. Her views were primitive, direct, and aimed at readily identifiable targets, both at home and overseas.

The aboriginals who lived among her own people were bad enough—they were a lazy, ill-disciplined, and grubby population of hard drinkers who, according to a book to which she gladly put her name soon after she won her seat in Parliament, ate their own babies and regularly cannibalized one another. Yet they were handed privileges in abundance, and they vacuumed up public money that should by rights have been spent on “mainstream Australians.”

Her views were no less sparing of peoples living beyond Australia’s coasts: she was especially contemptuous toward the Asians to her north:

“I believe we are in danger of being swamped by Asians,” she told Parliament in a truly splenetic inaugural address—in which she could say as she wished quite uninterrupted, as one of the courtesies that is customarily accorded to a maiden speech. “Between 1984 and 1995, 40 percent of all migrants coming into this country were of Asian origin. They have their own culture and religion, they form ghettos and do not assimilate. Of course, I will be called racist, but if I can invite whom I want into my home, then I should have the right to have a say in who comes into my country.

“A truly multicultural country can never be strong or united. . . . The world is full of failed and tragic examples, ranging from Ireland to Bosnia to Africa and, closer to home, Papua New Guinea. America and Great Britain are currently paying the price. . . . It is a pity that there are not men of . . . stature sitting on the opposition benches today. . . . Japan, India, Burma, Ceylon and every new African nation are fiercely anti-white and anti one another. Do we want or need any of these people here? I am one red-blooded Australian who says no, and who speaks for 90 percent of Australians.”

For a short while her message won a great deal of domestic traction. She wanted Australia out of the United Nations, a total end to Australian foreign aid, and, as her career progressed, ever-harsher limits on nonwhite immigration. The newspapers splashed her over the front pages for weeks. The popular Australian art form of talk-back radio was dominated by her, even though she had a voice that was as penetrating as a dentist’s drill. Television interviewers managed to find Mrs. Hanson Sr., who, over sweet tea and sticky buns, voiced her own fear, evidently inculcated in her daughter, that “the yellow races will one day rule the world.”

They also found Hanson’s senior adviser and speechwriter, and wondered why, as a man named Pascarelli, he should be so vehemently opposed to immigration. His answer was glib: “I was de-wogged.” And when Mrs. Hanson was asked if she was xenophobic, her lack of schooling offered up a reply, made after a brief and bewildered silence, of studied artlessness: “Please explain.”

But neither did her political opponents do much to advance the standing of Australia to the outside world, which watched bemused, even appalled. During a heated television discussion about why aboriginals had an alcohol problem, a well-meaning political critic demanded of Mrs. Hanson if she knew who the world’s greatest drunks happened to be? She didn’t. “White Australians,” he declared. “The biggest drunks ever known.” The notion that twenty-first-century Australia might ever revert to its old idea of keeping Asians at bay, while at the same time taking pride in a permanent national inebriation, caused a wave of shame to engulf the continent.

Which is perhaps why, by the turn of the millennium, the phenomenon of Pauline Hanson had begun to fizzle away. The country seemed swiftly to weary of her. She started to lose elections, then she lost money, and she went briefly to prison on fraud charges, though she was acquitted on appeal and released.

She tried hard to turn such occurrences to her political advantage. During her rise to prominence, she frequently claimed to have survived a childhood of “hard knocks”—and these new stumblings, she claimed, were just more of the same. Her remaining supporters found the suggestion engaging, as endearing evidence of her humanity. So, after only a brief hiatus, she was back in the running, and today she is still present, a slowly dimming star in the country’s political firmament, her drill-bit voice little more than background noise. But all the while, her political views have managed to hold the attention of not a few Australian voters, and so long as they do so, they manage, if unwittingly, to dull some of the luster of her country’s otherwise brightening public image.

Australia’s current harsh treatment of asylum seekers, most particularly those who attempt to come from Asia by boat, has served only further to damage this image of regional congeniality. The country’s current stand toward those would-be migrants hoping for safety and protection is that it will detain anyone who comes into its waters in the hope of refuge. No matter how violent the war back home, or how harsh the regime you are escaping, or how severe your risk of persecution, or how desperate your voyage—if you arrive by boat in “the lucky country”* without a valid visa, you will be locked up. Where you will go, under what conditions, and for how long are the only variables—and in recent years, the world’s human rights community has declared itself, over and over again, deeply troubled at the manner in which Australia, now essentially alone in the democratic world, has been dealing with what its politicians see as an intractable problem.

Boats laden with hungry, sick, frightened people, fleeing from a variety of conflicts and inhospitable situations in a variety of Asian nations, have been arriving in Australian waters since the mid-1970s, when the Communist takeover at the end of the Vietnam War first caused flotillas of crowded, unseaworthy, near-sinking vessels to set sail into the relative freedom of the South China Sea. For five subsequent years, the exodus of such Vietnamese went on. Most sought asylum in Hong Kong, nearby, or slightly farther away, in the Philippines. But the braver souls, or those in better-equipped boats, managed to navigate their way through the mess of Indonesian islands to the northern coast of Australia. The Canberra government of the day—Malcolm Fraser’s post-Dismissal government, as it happens—took a kindly view: more than fifty thousand were admitted. Then the situation in Vietnam eased, and the country’s frontiers were more keenly guarded. The boats stopped leaving. The South China Sea stilled. The Hong Kong camps were emptied. The coastal waters off Darwin and Cairns and Broome quieted. The problem, so far as Australia was concerned, seemed to be over.

But not for long. In 1989 it all started up again, this time with Indonesians, fleeing from poverty, dictatorship, and summary justice—or else making a quick run across the Arafura Sea in the hope of a better and more prosperous life. Or else they were Papuans trying to make it across the Torres Strait for much the same reason. Or else Afghans or Pakistanis, Burmese or Cambodians. Australia was to such people so close, so very tempting, so empty, so rich, so clearly in need of those who could, and would be willing to, work.

Invariably by now the fleeing thousands had the help (bought at great cost) of gangs of “snakeheads,” the people smugglers eager to cash in on those impoverished Asians desperate to get to the bright lights and big opportunities of Australia. But this time Australia reacted, harshly. It had no room for more, it said; Australian workers were bitterly complaining about the low-cost newcomers who were now plundering their jobs. The detention policies that still exist today—draconian, harsh, criticized—were slowly and steadily brought into force. And since that time, with the policies and their manner of implementation ebbing and flowing and shape-shifting as the various governments in Canberra have changed their views, so the matter of dealing with arriving boat people has proved to Australia a practical and humanitarian challenge without end or answer.

A so-called Pacific Solution was brought into force in 2001. It ebbed and flowed and shape-shifted, too; and though it now has an extra aspect with an extra name, Operation Sovereign Borders, Australia’s Pacific Solution remains, in essence, the policy of today.

Under its rubric, three island camps were opened to accommodate the hopeful masses, and all remain busily active today. One is on Christmas Island, an Australian territory in the Indian Ocean. Two others are on foreign-owned islands, and the Australians pay to have them there. One is in Papua New Guinea, on the Admiralty Island of Manus, which was made briefly famous by Margaret Mead, who lived in its rain forests after World War II. The other is on the former phosphate-rich equatorial Pacific island of Nauru, which in the 1960s claimed to be the richest per capita state on the planet, but which is now a devastated wreck—a played-out environmental disaster zone; an independent state associated mainly with flagrant corruption, money laundering, a population of nine thousand, and, in recent years, the third of the Australian detention centers for would-be immigrants.

The camps in all three sites are dreadful and dismal places, filled to bursting with Afghans and Tamils and Pakistanis and Syrians fleeing from war zones or from the Taliban or from ISIL or from a host of other despots and desperadoes. All the incarcerated, some held for the many years that it now takes to process their applications for Australian residency (which most likely will be denied), took months to find their way to this place. Most of them fled first to Indonesia, waiting for countless months in dreadful conditions, before taking to the sea and to what all hoped might be the sanctuary of Australian waters. But there, instead, were the ever-watchful ships from the Australian navy, determined to prevent them with force from ever reaching Australian territory and thereby being able to claim refugee status.

I was in Darwin in the November summer of 2014; and all the local talk was about the customs boats that left the little port, their crews scanning the hammered-pewter surface of the sea, looking for the tiny and barely seaworthy craft that had come down from Java or Sulawesi or the Banda Islands, and intercepting them and brusquely scooping up their passengers. They would take them on next to Manus or Nauru—or even to Christmas Island, which the Canberra government had, with Orwellian cunning, deaccessioned, ensuring that any migrant who managed to land on its shores could not claim to have landed on Australian soil. Christmas Island was indeed, legally and constitutionally, still sovereign Australian territory—except, technically, for the sole purposes of immigration, when it is deemed to be a foreign place.

Not that landing on Christmas Island was ever easy. In December 2010 a boat crashed into the cliffs of the island’s Flying Fish Cove, tossing scores of its passengers into the raging waters. Forty-eight of them died, their drownings witnessed by hundreds ashore. It was a dreadful tragedy—yet the Australian government simply used it as justification for the national policy of prohibiting boats from trying to reach land. Keeping the boats away would prevent disasters like this from happening again, the government said. Interception by armed warships was for the refugees’ own good.

The Christmas Island tragedy of 2010 served to diminish still further the luster of Australia as a would-be model member of the western Pacific’s Asian community. Canberra’s immigration minister of the time hardly helped when he complained publicly upon learning that his own government had paid for some family members to attend the funerals of the victims. When asked if he thought it was heartless to complain that a man who had lost his wife and two young children to the sea had been given a compassionate flight to the graveside, the minister went on the radio to declare that the cost of the man’s flight was unreasonable. Few thought the minister anything other than entirely pitiless.

On the one hand, pitilessness; on the other, compassion. The difference is stark, and serves as a vivid reminder of the two very separate Australias that still exist. On the one hand is the delightfully nuanced and multicultural urban Australia, with Sydney and Melbourne now among the most gorgeously admixed cities to be found anywhere in the world, representative of an Australia as a pitch-perfect member of the western Pacific community. On the other, however, stubbornly displayed by a residue of politicians and would-be politicians (Pauline Hanson a type specimen), is an Australia remarkably and woefully out of touch with and unsympathetic to the ways of the Asian world. The two sides of the argument, an argument long settled in almost all other former British colonial possessions, encapsulate a nagging and potentially serious problem.

For is this enormous, wealthy, talented, and truly fortunate country part of the Pacific, a real working component of the great engine work of Asia? Or is it still an outpost of Olde England, a place of beer, bellies, and bogans, set dustily down on the western edge of this mighty sea? It seems in part to want to be Asia, to play its role, to be a powerful component and a moral counterweight to China, to be a place of well-mixed values and of tolerance and understanding, and of a people who present, in and of themselves, a microcosm of the very ocean that washes the continent’s shores.

But there is an awful undertow at work still as well, a concatenation of white-dominated, blinkered, complacent, and reactionary forces that may yet keep this once lucky place pinioned and fettered firmly in its past, and thereby not allow it to become a true member of the community in which geography has settled it, now or maybe for some long while to come.

A great place to live, as a friend in Sydney said to me one evening. A great place to live. But not a great country. Not yet.