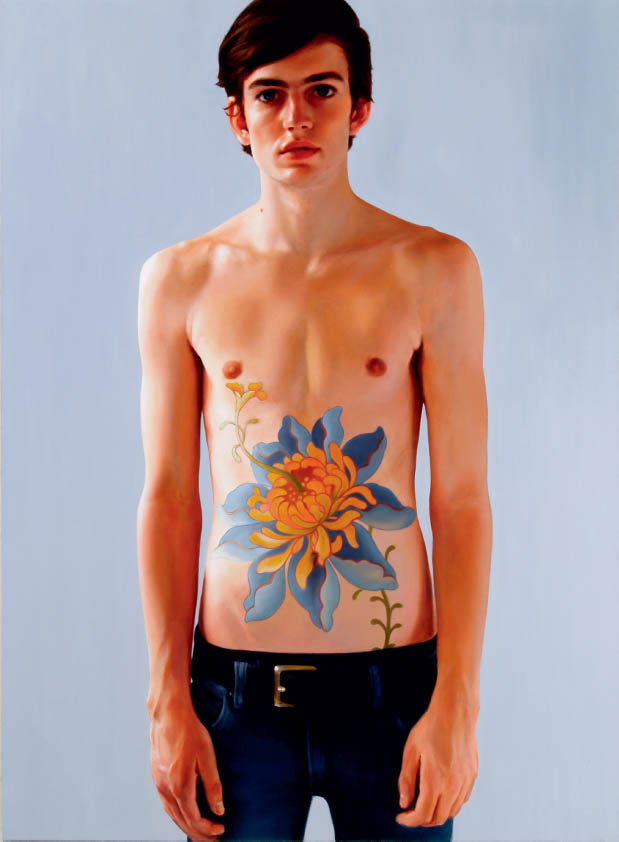

Deidre But-Husaim is a full-time painter in Adelaide, Australia. Not only are her large-scale realist portraits stunning, but her studio is also amazing. Now converted into a series of art studios, the building in which it is housed used to be an incinerator designed by the famous architect Walter Burley Griffin in the 1930s. Deidre attended Adelaide Central School of Art, where she completed an associate degree in visual art, and Adelaide Centre for the Arts, where she received her bachelor of visual art. She’s had several successful solo exhibitions in Melbourne and Sydney, and has many awards under her belt, including the Sulman Prize, Doug Moran Prize, Redlands Art Awards, John Fries Memorial Prize, and the RBS Emerging Artist Award, and she was a finalist for the Archibald Prize—just to name a few.

JC—Which artist(s) do you admire most, and why?

DBH—I love the master painters Rembrandt and Velázquez: Rembrandt for his wonderfully intense portraits that have such a tactile quality to the paint itself, and Velázquez for his economy of mark making, especially in his later works, where every mark appears to be so confidently placed.

JC—Have you ever experienced a creative block?

DBH—No, but I’ve experienced what could be referred to as creative confusion. Sometimes I have too many ideas at once, and can’t decide which is the good one. Not everything we “think” is a good or interesting idea should be made into work.

JC—Do you have a process you turn to when you’re having trouble with a painting?

DBH—Yes. I stop and spend at least twenty minutes just looking at my work. It’s easy to get caught up in the act of painting and forget to step back and look. I locate my palette approximately three meters away from the actual work so that when I load my brush I have to step back and look at my painting from a distance. I also have a mirror hung on the wall opposite to my easel, allowing me to see the painting in the mirror when I turn to go to my palette. This is helpful, as it gives more viewing distance and a more overall and complete view.

JC—Do you have any qualms about throwing your work away if it’s not working?

DBH—No. If a work fails, I have to get rid of it for it to be completely out of my thoughts. If it’s truly not working I throw it out, but that’s not until I have sliced it up with a box cutter. This resolves the problem extremely efficiently, and prevents a lot of wasted time working on a “problem child.” Although it is a bit scary, it’s very freeing, and allows you to start fresh.

JC—How do you handle criticism?

DBH—Not very well. I’m human. I think to myself, “What would John Lydon [Johnny Rotten] do?” . . . and then I get back to painting.

JC—You are a very busy full-time artist. Do you have any time for personal projects?

DBH—I don’t usually have time for them outside of my exhibiting commitments, but currently I have made time for a body of work consisting of small paintings to raise money and awareness for Acid Survivors Foundation in India. This is an organization that works toward the elimination of acid and other forms of burn violence, and offers support for the survivors of this horrendous crime. You can learn more at AcidSurvivors.org.

JC—That is a wonderful way for you to use your talent! Are those pieces similar to the work you’re known for, or are they quite different?

DBH—These pieces are small studies that allow me to “play” and explore ideas that are at times an extension of my ongoing body of work, and at other times completely different subject matter.

JC—Where do you find inspiration?

DBH—In the act of painting. I paint every day, and one painting leads to the next in a natural way. For me it’s important to make work that is about now, about the time we live in, and what surrounds us. I think it’s extremely important to evolve your practice and challenge yourself conceptually and technically. It would soon become tedious otherwise.

JC—And finally, if you weren’t an artist, what would you be?

DBH—A trapeze artist, a sky diver, a martial arts specialist, a wild horse.

I think it’s extremely important to evolve your practice and challenge yourself conceptually and technically. It would soon become tedious otherwise.