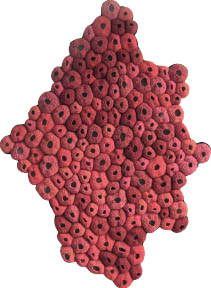

It’s like a biology textbook and a ball of yarn fell madly in love, got married, and had a few babies. New York–based artist Emily Barletta is the very talented matchmaker who got these crazy kids together, and the reason is that as a youth, Emily was diagnosed with a spinal disease that altered her life, but ultimately led her to art. (In fact, most of her crochet hangings and objects are meant to represent diseased cells!) In 2003 she received her BFA from the Maryland Institute College of Art, and now creates work that beautifully blurs the line between science and art, not to mention art and craft. Crochet, clay, beadwork, and embroidery on paper. Absolutely gorgeous.

JC—Clearly it doesn’t define you, but could you talk about your illness, and how it has impacted your life, and art career?

EB—When I was twelve years old I started to grow a hunchback and was diagnosed with Scheuermann’s disease. I had a severe case that required having reconstructive spinal surgery when I was fifteen, and two other surgeries after that. I was in a great deal of physical pain throughout my teenage years. There is a certain amount of emotional isolation that goes along with having a deformity and living in constant physical pain. However, having Scheuermann’s disease is the thing that brought me to art. When I was a young teenager, and my body was out of my control, making art became a way for me to express the emotional and physical trauma I was experiencing. As I developed into an adult artist, making art became the way that I processed and expressed all of my feelings, not just the ones about physical pain. It’s the filter through which I see and record all of my life. But when I was young it was therapeutic, and it saved me.

JC—Incredible. Was it during those teen years that you started to feel like an artist?

EB—Yes. When I was sixteen or seventeen I had a goofy, unrealistic idea of myself as an artist. I wanted to go to art school and learn to illustrate children’s books. This was a very short-lived dream. During art school I thought I would work at a bookstore and draw privately in my sketchbooks forever. About a year or so after I graduated, thanks to some positive encouragement, I realized that the objects I was creating privately could be art.

JC—Where do you find inspiration?

EB—I enjoy learning and reading. When I work I listen to audio books and a great deal of podcasts. I like going to museums to see art, but the American Museum of Natural History, New York Aquarium, and the Brooklyn Botanical Gardens are among my favorites. I like going out into nature, especially near water of any kind. In the city I like to take long walks, and just look.

JC—Which artist’s work are you most jealous of, and why?

EB—Louise Bourgeois. Her work makes me feel so much, and I strive to create work that could hopefully have a moving emotional experience for the viewer.

JC—Would you throw a piece away if it’s not working, or would you just keep going until you’re happy with it?

EB—I’m a huge fan of throwing things away, or taking them apart. At art school there wasn’t enough emphasis on the idea that it was OK to make bad art. In my own practice I had to learn that I don’t like everything I make. Not every beginning is going to be a finished work. Now I’m good at realizing when it’s not what I want, accepting it, and just chucking it to begin again.

JC—But your work is so meticulous! What do you do if you’re quite far along with a piece, and you “make a mistake”?

EB—The embroidery on the paper can be more forgiving. I have been known to spend forty hours embroidering something only to rip out all the stitches and start over again, working with the holes already in the paper. I tend not to view specific stitches as mistakes; I think they add a bit of personality to the work. For me it’s sort of all or nothing that way: I’m usually satisfied with the overall look—or not at all.

JC—Do you ever equate your self-worth with your artistic successes?

EB—It’s impossible not to feel a bit of an ego boost when success comes. Then after a show, when everything has slowed down again, it’s hard not to feel a bit lower. When I’m in the studio, working, I tell myself that everything I make will have a home or a purpose someday. Then when I’m done making it, I just pack it up and put it in the closet. I make art because the process of making art makes me happy. Being successful with it and doing it for personal fulfillment are separate ideas.

JC—Do you ever hear your inner critic?

EB—My inner critic is judgmental and opinionated. On John Cage’s “Some Rules for Students and Teachers,” number eight is “Don’t try to create and analyze at the same time. They’re different processes.” I struggle with this a great deal, and try to remember this rule and stick to it.

JC—Have you experienced creative blocks?

EB—Yes, some have lasted for months or even a year, which was painful!

JC—How do you push yourself through something like that?

EB—I look for inspiration outside myself. I push myself to keep making things, even when I’m aware that the thing I am making is going to end up in the trash. Sometimes I stare at the wall, but I find it’s more helpful to just keep drawing and sewing and moving my hands and hoping for a breakthrough: eventually one comes—usually. I think they pass on their own, and it’s just a matter of time.

Not every beginning is going to be a finished work.

I make art because the process of making art makes me happy.