STAVE V

The End of It

Scrooge had but few moments to observe the change that overcame his partner as Cratchit looked around the room and his eye fell on the blue paper cover of the monthly installment of the novel he had been reading a lifetime ago, it seemed. Though tears still dampened his cheeks and his breath came in choking sobs, he nonetheless realised the import of where that booklet lay—not on the floor, where it had fallen when he had been startled by Scrooge’s arrival, but on the table by his chair, where it had lain before he had begun his night’s reading. Cratchit rounded on Scrooge, a smile breaking across his face.

“It is not thrown down!” cried Cratchit, pointing a shaking finger towards the table. “It is not thrown down upon the hearthrug.” With this, he snatched the booklet off the table and clutched it in his hand with a violence that would likely have displeased the author. “It is here!” he cried, shaking the booklet at Scrooge. “I am here; the shadows of the things that would have been may be dispelled. They will be. I know they will!”

But even as Cratchit’s tears of terror and remorse turned to tears of joy and resolve, Scrooge felt himself drifting away from the scene and all that had lain before him. The threadbare chair, the table bearing the extinguished lamp, the kitchen awaiting the arrival of Mrs. Cratchit, and the trembling figure on the floor faded away and the sound of Cratchit’s sobs became the ticking of the clock on Scrooge’s own chimneypiece. The same warm air drifted in at Scrooge’s window, but as he threw up the sash and stuck his head out into the London morning, the old man found that the weather had broken, and the oppressive humidity of yesterday had given way to crisp, clean air, warmed by the summer sun but wrapped in the promise of cool autumn days to come.

“Hallo!” he shouted at a boy who made his way along the street below. “Can you tell me what day it is?”

The boy, who was not previously acquainted with Scrooge’s eccentricities, cast a puzzled look upwards and, seeing no harm in the old man, shouted back, “Twenty-third of June, sir.”

“They’ve done it again!” cried Scrooge with glee. “The spirits have done it all in one night. They can do anything they like. Of course they can. Of course they can.”

You may never have seen such a thing as a man who has passed four score years on this earth dancing a jig in his nightshirt on a summer morning, but I assure you it is a sight well worth seeing, and one that would have provided you with plentiful laughter had you been in Scrooge’s apartment that morning to see it. And had you been there, you might also have understood the expression “in a twinkling,” for Scrooge’s eyes never stopped twinkling in anticipation of the visits he planned to pay that morning.

As he hurried through the crowded morning streets after making himself presentable, even those who knew Scrooge well and were accustomed to his unseasonable greetings thought they detected an extra degree of enthusiasm in his bellows of “Merry Christmas!” and “Happy New Year!” He carried his walking stick only so he could swing it with gusto, wore a hat solely that he might tip it at every passing lady, patted the head of every child who ventured within his reach (and a few who tried, but failed, to give him a wide enough berth), and stuck his head in every shop he passed to remark on the fineness of the day, the fineness of the meat (or books, or pastries, or whatever was on offer), and the fineness of Christmas, which, by the way, he hoped would be merry for all.

Scrooge’s first stop was Whitehall, where he expected to find his nephew perched on his stool and hard at work. However, though the morning had advanced past the point at which civil servants can generally be counted upon to be adding up columns of numbers for the good of England, Freddie’s stool stood empty.

“Haven’t you heard?” asked the clerk on the adjacent stool. “He talked as if it were all your idea.”

After wishing the fellow the merriest of Christmases, Scrooge enquired as to the nature of the idea attributed to him.

“Freddie’s decided to run for Parliament,” said the clerk. “There were some in the office who found it quite a shock, I don’t mind telling you; but many of us wondered what took him so long. I always knew he could do it.”

“Do what?” asked Freddie with a scowl, for he had just arrived at the door.

“Ah, there you are, nephew,” said Scrooge. “I had hoped I might have a chat with you this morning.”

“A chat?” replied Freddie sternly. “I should think there are more important things in this world than chatting with one’s uncle.”

“And what might those be?” asked Scrooge, concerned with this unexpected standoffishness in his nephew’s demeanour.

“Why, wishing him a Merry Christmas, for a start!” cried Freddie, breaking into a smile and throwing his arms round his uncle. “And a Happy New Year, uncle, for it is a new year for me. A new year and a new life all beginning today, thanks to you.” Freddie pulled his uncle by the sleeve into a corner of the room hidden from the other clerk by a filing cabinet and whispered, “All those years ago, when you told us about being visited by those spirits—we all thought you’d gone a bit potty, you know. Most of the family still think so, though they’d never say it to your face. But, oh, uncle! What a night! What a revelation! I never understood before now.” And unable to think of what to say next, he again embraced his uncle with another “Merry Christmas,” hearty enough to be heard clearly by the clerk who put so much faith in Freddie’s future.

If Scrooge had hoped to chat with his nephew, he found the chat rather one-sided, for it was nigh on impossible for him to squeeze a word into Freddie’s unstoppable torrent of excitement. Like the surf in a winter storm came Freddie’s ideas, one after the other, without a moment to catch one’s breath in between whiles. He would propose this and he would do something about that; he had a plan for one problem and an idea about another. If Freddie had been made dictator of the empire at that very moment, I daresay the world would have been a much better place in a fortnight, but Scrooge knew that even as a lowly backbencher Freddie could, and would, do much good, and he might well rise through the ranks to higher and more influential posts as the years went by. He smiled as Freddie spoke, but after a time Scrooge did not hear every word his nephew said, for he thought he might hear, faintly on the wind, another sound—the sound of chains falling to the ground, link by link. If Freddie accomplished one-twentieth of what he set for himself, Marley would certainly be a free man.

It took no small effort for Scrooge to extricate himself from the conversation, and it was only when Freddie realised that he was late for a meeting with a gentleman likely to back his candidacy that Scrooge was able to bid his nephew farewell and press on to his next destination.

Up Whitehall to Trafalgar, up the Strand and Fleet Street and into the City strode Scrooge, whilst a sea of Londoners parted in front of him, none quite sure how to respond to his wishes for a Merry Christmas. When he arrived at the bank, his request to see the Messrs. Pleasant and Portly was met with a blank stare by the clerk in the cage. Laughing at his own foolishness, Scrooge enquired after the bankers again, this time using their proper names, which he had somehow managed to remember (when he thought it over afterwards, he suspected that Marley, who surely would have known, had whispered the names in his ear).

The clerk informed him that the two bankers he sought were engaged in a highly important conference with a highly important client and were not to be disturbed under any circumstances unless they were to receive a visit from one Ebenezer Scrooge.

“But I am Ebenezer Scrooge,” he said, laughing.

“He is, you know,” said the clerk in the next cage with a roll of his eyes. “Though I’m surprised he hasn’t yet wished you a Merry Christmas, it being June.”

The first clerk, who was evidently new to the position, did not think Scrooge looked the sort of man for whom one ought to interrupt a highly important conference, but since two newly arrived customers were even then greeting Scrooge by name and being wished a Merry Christmas, there seemed to be no doubt about his identity, so the clerk led him away down a long narrow corridor and through a series of heavy oak doors until they arrived in a dim and stuffy anteroom.

“One moment, please,” whispered the clerk, who proceeded to stand by the largest oak door they had yet encountered for nearly a minute before he ventured a timid knock. This effort was met with utter silence.

“I’m sorry,” whispered the clerk. “Perhaps they didn’t want to be disturbed after all.”

“Nonsense!” cried Scrooge, elbowing his way past the clerk and banging on the door with the handle of his walking stick. Before the clerk could restrain him, the door opened slightly and the scowling face of Mr. Portly appeared.

“I’m sorry, sir,” muttered the clerk, “I tried to . . .” But what he tried to do Mr. Portly never discovered, for as soon as Portly saw Scrooge, he swung the door open and grinned with delight.

“Mr. Scrooge, what a pleasure! What a delight. We’d no idea you would honour us so soon with a visit.” The befuddled clerk took this opportunity to make his exit, and Mr. Portly grabbed Scrooge by the hand and, shaking vigourously, pulled him into the inner sanctum in which the highly important conference was taking place.

The room might easily have contained Bob Cratchit’s entire house; Freddie’s family might have comfortably lounged in the fireplace; the table was as large as the stage of a West End theatre; and the woman who sat at the table (next to Mr. Pleasant, who now jumped from his seat to greet Scrooge by shaking the hand not claimed by Mr. Portly) wore a diamond ring that might, if pawned, have covered the weekly deposits in the bank with change left over for Sunday dinner.

“We’re so pleased you’ve joined us, Mr. Scrooge,” said Mr. Pleasant, apparently loath to release Scrooge’s hand until the old man was comfortably seated in a chair large enough that it might accommodate (and the thought occurred to all three men at once) the Ghost of Christmas Present.

“This is Mr. Scrooge,” said Mr. Portly, turning to the lady, who sat patiently at the far end of the table.

“Yes,” added Mr. Pleasant, as if she might not have heard (and she was, indeed, quite far away), “this is Mr. Scrooge.”

“It’s a pleasure to meet you, Mr. Scrooge,” said the lady, with a slight nod of her head.

Scrooge was on his feet again as soon as Messrs. Pleasant and Portly dropped his hands, and he skipped around the table to where the lady sat so that he might offer a proper greeting. Taking a deep bow, he said, “The pleasure is all mine,” and then, looking her straight in her deep-set blue eyes, he added, “And may I take the opportunity of wishing you a very Merry Christmas.”

The woman’s face, which had remained unmoved up to this point, now showed the slightest flicker of what might have been delight or amusement or both, and she said in a soft voice, “I thank you, sir, and a Happy New Year to you and your family. Mrs. Aurelia Burnett Crosse at your service.”

“Ebenezer Scrooge at yours. I do hope I’m not interrupting.”

“On the contrary, sir,” said Mrs. Crosse, “we were only just bemoaning your absence. Your arrival could not have been more propitious.”

“Mrs. Crosse is one of our very best clients,” said Mr. Portly.

“One of their very wealthiest clients, he means,” said Mrs. Crosse with a laugh. “I’m afraid, Mr. Scrooge, you’ll find me quite inept when it comes to the old stricture against talking about money. I have quite a lot of it, and, as I’m sure your friends here will tell you, there are days on which I talk of little else.”

“You see, Mr. Scrooge,” said Mr. Pleasant excitedly, “after our . . .”

“Our adventure last night,” continued Mr. Portly.

“Yes,” said Mr. Pleasant. “After our adventure, we decided we would find a way to help some of those people we met and to . . .”

“To cover some of your cheques!” cried Mr. Portly.

“Exactly,” said Mr. Pleasant. “To cover some of your cheques.”

“And there is no one in London more suited to the task of covering cheques than myself,” said Mrs. Crosse.

“So you see,” said Mr. Portly, “we’re forming a little society.”

“The Scrooge Society,” said Mr. Pleasant.

“Yes, the Scrooge Society,” continued Mr. Portly. “We’ve asked a few of our best clients.”

“Your wealthiest clients,” said Mrs. Crosse with a twinkle in her eye.

“As you put it,” said Mr. Portly, “our wealthiest clients. We’ve asked them to join this society and to start a fund to be used for the relief of distress.”

“With the funds to be dispensed at the sole discretion of Mr. Ebenezer Scrooge!” cried Mr. Pleasant.

“And when I leave, Mr. Scrooge, you shall have a thousand pounds at your disposal, so you’d best get to work, because I assure you there is more where that came from.”

Scrooge could not hide his delight, and there followed a period of hand shaking and backslapping and Merry Christmasing such as had not been seen in that hallowed chamber for many a year (if, in fact, the eyes of the portrait above the chimneypiece had ever witnessed such a display). Scrooge agreed to dine with Messrs. Pleasant and Portly the following day to discuss the details of how the charity they had insisted on naming in his honour would be administered. For the moment, though, he said that he must be going, as he had a rather important visit to pay.

It was past his usual luncheon time when Scrooge arrived at his place of business, but earthly hunger had no effect on him that day. He was pleased to find the offices shut tight, and no sign that they had been occupied since the previous evening.

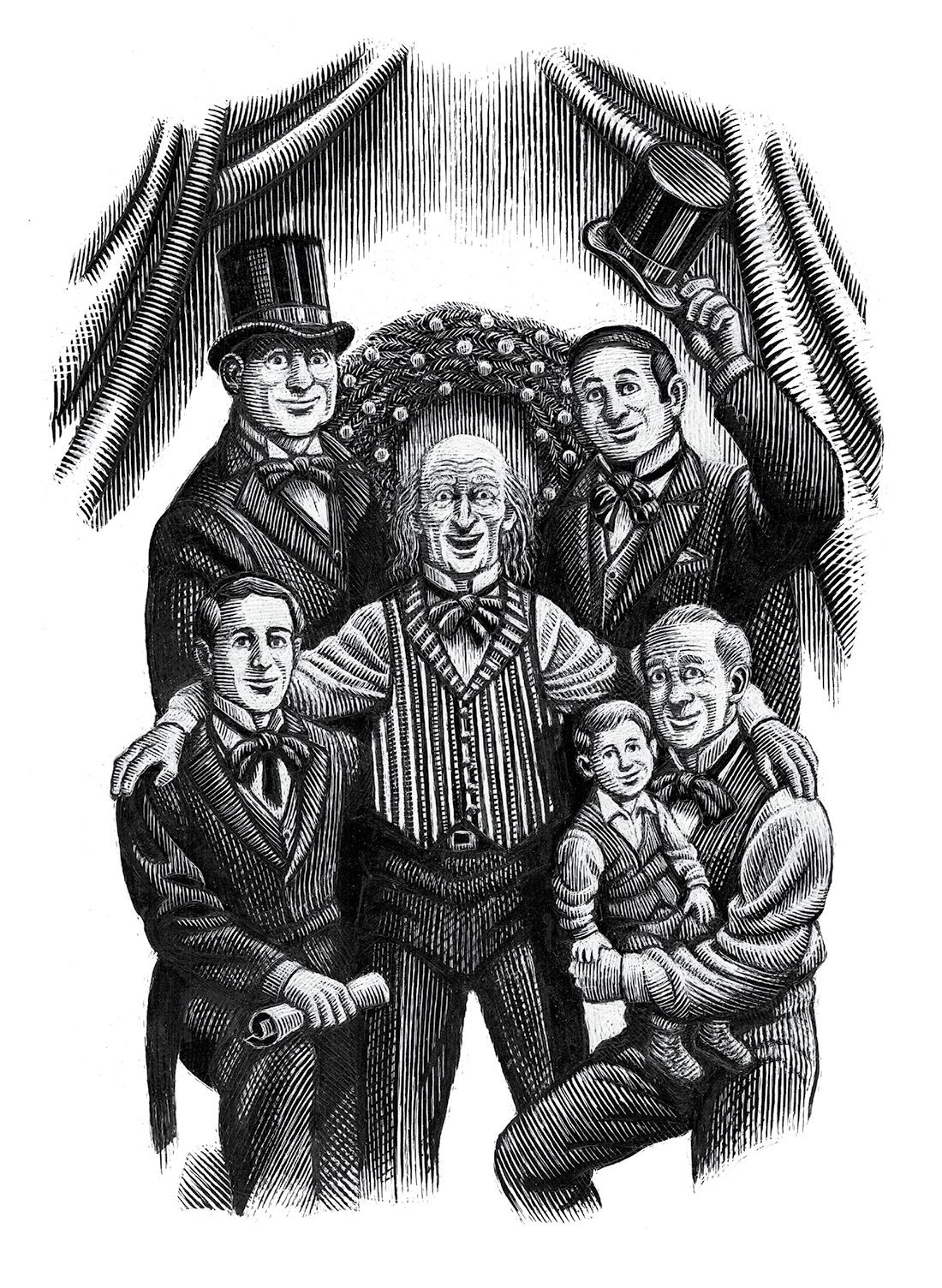

Scrooge’s last visit of the day was brief. He shook no hands, slapped no backs, made no bows, and wished no one a merry anything. The street on which Timothy and Lucie Cratchit lived was, like their home, neat and modest. At two o’clock on a summer afternoon, it was empty of pedestrians, save for an old man in a colourful waistcoat strolling slowly away from the Cratchit home, a tear glistening in his eye. Scrooge had arrived at the Cratchits’ only a few moments earlier and, peeping over the garden wall, had observed his partner, Bob, on his hands and knees in the garden doing a passable impression of a lion, whilst his grandson toddled towards him. Scrooge did not watch long enough to discover if little Tim was playing the role of big game hunter or lion tamer; he had seen enough to know that his work was done.

• • •

Scrooge half-expected another visit from Marley that evening, and sat up reading for some hours (long enough to see the young boy in the novel become a young man) before he despaired of a visit from his friend. It was nearly autumn when Marley did return, a night with a bite in the air cold enough that Scrooge entertained thoughts of a closed window and a fire in the grate. If a spirit can be said to smile, on that night Marley did. His chain, he said, was considerably lighter thanks to Scrooge’s machinations, and growing lighter every day. It was nearly four years before Marley paid his final visit, and on that occasion Scrooge’s late partner, overcome with emotion, could only mumble a simple thanks for the rest that was, at last, about to come his way.

Cratchit continued to work hard, but he left the office after lunch every Tuesday and spent the afternoon with his grandson; Scrooge saw to it that Cratchit’s income did not suffer for this indulgence. Tim always looked upon his grandfather with eyes full of love, and would consider the hours the two spent together amongst the happiest of his childhood. As Cratchit’s life became blessed with additional grandchildren, he spent more time with them and less at the office, until Scrooge convinced his partner to take early retirement and to hand the reins of the business over to his son. From that day forward, not a day passed when Cratchit did not bless the life of some member of his increasing family with an act of kindness or a display of love, and it was said by those who knew him that he taught all the Cratchit grandchildren the true meaning of family and that they would doubtless carry this lesson forth in the world as they married and had children and grandchildren of their own.

Freddie did his best to be a great reformer, and though he never became prime minister, he did attain various positions of influence and he was often, behind closed doors, the initiator and driving force behind many of the social improvements in the ensuing two decades. In his retirement, he continued to administer the charity founded in honour of his uncle.

The Scrooge Society (which eventually included several members of Parliament in addition to Freddie) met for luncheon at the club of Messrs. Pleasant and Portly every Wednesday. Scrooge had wanted to change the name to the Wednesday Club, but the members insisted that the name reflect the role Mr. Scrooge had played in all their lives. These pages are too brief to enumerate all the good the society did as the years passed, but many a desperate Londoner had his life transformed by the generosity of its members, and though the money they gave away was not, strictly speaking, Scrooge’s, they nonetheless depended on the old man’s guidance. And Scrooge’s understanding of the people of London, coupled with his genuine belief that they were, as his nephew had said so long ago, fellow passengers to the grave, always steered the society towards accomplishing true change in the lives of the people it touched.

Scrooge never stopped wandering the streets of London, looking for places where he might spread the spirit of Christmas and wishing the passersby a happy holiday. And though he preferred to be known as an eccentric old man rather than as a benefactor, Scrooge was not quite so anonymous as to have his deeds go wholly unrecognised. And so it was that, on occasion, whilst strolling down the Strand or when stopped before the window of a bookshop on Charing Cross Road, Scrooge would encounter some former beneficiary of his kindness, and that fortunate soul, be it man, woman, or child, would invariably greet him with a hearty, “God bless you, Mr. Scrooge,” to which Scrooge would as invariably reply, “God bless us, every one.”

The End