AVIATION BEFORE WORLD WAR II had been for the pioneer, the daring record-seeker, the sportsman pilot, a few relatively wealthy travelers, government officials, and the military.

A new Lockheed transport, the company’s first large one, would carry more people farther and faster and more safely than ever before, and economically enough to broaden the acceptance of flying as an alternative to train, ship, and automobile.

The Constellation was a tremendous challenge to Lockheed. It was our first attempt to enter the large-size transport field. Describing the company state of mind at the time, Hall Hibbard has said, “Up to that time we were sort of ‘small-time guys,’ but when we got to the Constellation we had to be ‘big-time guys’… We had to be right and we had to be good.”

Our commercial Model 14, so successful as the Hudson anti-submarine patrol bomber and the related Model 18 Lodestar—really a stretched Electra—were not large enough to compete in the expected post-war commercial air travel market.

Anticipating the future well before the war, we had worked on new designs, including Model 27, a canard, with horizontal stabilizer and control surfaces in front of the main supporting surfaces—or simply, with tail in front. We built a mockup but had the sense not to pursue this into production. The canard was impossible to make safe at high angles of attack—as the Russians later discovered with their supersonic TU-144 that crashed at the Paris Air Show in 1973.

Another was the Model 44 Excalibur, a very good “DC-4” in advance of the DC-4. It held considerable promise, and Pan American Airways expressed interest. Again, we built a mockup. Fortunately, we did not build it in prototype, as it would have been too small for competitive over-ocean service.

Then, in 1939, Howard Hughes as principal stockholder and Jack Frye as president of Transcontinental & Western Air, Inc., had asked Robert Gross if a transport could be designed to carry 20 sleeping passengers and 6,000 pounds of cargo across the US nonstop and at the highest possible cruising speeds. They suggested between 250 and 300 miles an hour at an altitude around 20,000 feet.

We abandoned our earlier studies and concentrated on the new airliner for TWA. What we proposed—Robert Gross, Hall Hibbard, and I—to Hughes at a meeting in his Muirfield Road residence in the elegant old Hancock Park section of Los Angeles was a larger airplane, capable of flying across the ocean and carrying many more people. We reasoned that it was economically unsound to carry only 20 sleeping passengers when we could accommodate more than 100 people in the same space with normal seating. Our design was capable of flying transatlantic with the Wright 3350 engine already in development for the military B-29 bomber. It was the world’s largest air-cooled engine.

Few people not involved directly realize what a tremendous job it is to design, test, and build a new type of aircraft. And the larger the airplane, the more difficult are some of the problems. For example, the horizontal tail area of the Constellation was greater than that of the early Electra’s entire wing.

The Constellation was first with many design features for passenger airliners. It was the first airplane to have complete power controls—that is, hydraulically “boosted.” The basic principle of mechanically enhancing the human effort had been used in steamships, cars, and trucks, but the application to aircraft was much more complicated. Lockheed earlier had undertaken it as a long-range research project in anticipation of the greater control problems to come as aircraft performance increased. It was decided early to incorporate the device in Constellation design.

I had some difficulty in convincing Robert Gross of the advisability of adding this complexity to the airplane, since other aircraft manufacturers were ignoring it. Why did we need it? But I caught him one day when he had just parked his new Chevrolet in the company garage.

“Bob, you didn’t really need power to steer that car, but it makes it a hell of a lot easier, doesn’t it?” I never heard another word of dissent about power steering for aircraft.

The new airliner was to be faster, at 340 miles per hour top speed, than many World War II fighters. This soon was increased to 350 mph. Unlikely though it may seem, the Constellation transport used the same wing design as the P-38 fighter—larger, of course, and with an improved version of the Lockheed-Fowler flaps.

Its pressurized cabin allowed comfortable flight at 20,000 feet, above 90 percent of weather disturbances. It was the first airliner with this capability. Our early work on the XC-35 contributed importantly here. The airplane had excellent performance on just two of its four engines. And those powerful engines gave it an easy transcontinental and transatlantic nonstop range.

There were other innovations for transports introduced initially or in later development: integrally-stiffened wing structure, reversible propellers, turbo-compound engines, wingtip fuel tanks, and a detachable streamlined cargo pack carried under the fuselage.

That “Speedpak,” the under-fuselage baggage carrier, was a very good concept and still is. It cost only 12 miles an hour in lost speed because of extra aerodynamic drag, and the passengers’ baggage always was right there on landing. I wish we had done more with that; it never really caught on. Of course, airports were nowhere near so busy as they are today.

Six different wind tunnels were used in development of the original Constellation design. Most of the tests were conducted at the University of Washington and Lockheed’s own tunnel, but supplementary tests were undertaken at Cal Tech and in NACA’s high-speed tunnel, spinning tunnel, and 19-foot tunnel.

Engines were tested not only in ground runup but in flight, installed in a Vega Ventura. One in the ASW series of aircraft, this was produced by a Lockheed subsidiary. It gave us a flying test bench for the Constellation engine. Installation was based on several years of work by the Civil Aeronautics Board on fire prevention, warning devices, and fire-extinguishing methods. Despite these precautions, we later would have a temporary grounding of the airplane because of fire.

Development work on the Constellation led to establishment of a second major research and development facility at Lockheed—a laboratory for mechanical and structural testing of aircraft structure and systems. We had built a full-scale fuselage mockup of the airplane. Then, because of the complexity of hydraulically boosting the entire control system, we built a mockup of that alongside the cabin mockup.

With our limited space, this all was so crowded and so unprofessional looking that Messrs Gross and Hibbard took pity on us. “All right, we’ll go for a research lab,” Gross allowed. We had a start on the very extensive and sophisticated research and development facilities that exist at Lockheed today.

We built our new research lab next to the wind tunnel and made it large enough so that we could represent in full scale the entire control system of the Constellation from cockpit to tail. We could provide the equivalent of air loads on the control surfaces by the use of very heavy springs. This is how we developed what was the first power-boosted control system for any airplane.

The electrical system on the Constellation was another of those mocked up. This served a second purpose later when a TWA plane crashed on a crew training flight. The cockpit had filled with smoke from an electrical fire. We were able to reproduce conditions in the lab and also simulated the smoke conditions in actual flight—but we wore gas masks.

In the TWA tragedy, a short circuit in an electrical fitting had set fire to oil-soaked insulation and an open door then had allowed smoke to enter and blind the pilot and copilot. Our accident investigation resulted in some redesign with extra protection against the possibility of engine fire.

That “Day of Infamy,” Sunday, December 7, 1941, put a hold on all commercial aircraft production. After Pearl Harbor, the Constellation project was stopped by military authorities who wanted Lockheed to concentrate on Hudson, P-38, and other war production. The Vega company, in pool with Boeing and Douglas, was to produce the B-17 bomber and abandon its original plans to build small civilian aircraft.

The Air Force, fortunately for the Constellation program, saw a need for military transport aircraft to carry large numbers of troops. The Constellation was “drafted.” But its production was stalled 17 times by the military during the war because of the priority of other projects when the production people were needed elsewhere.

The Constellation made its first flight on January 9, 1943, in military olive drab paint, as the C-69. We had delayed the flight for two days because of very high winds—too high for a first flight with a large, new transport. The press corps—radio and newspaper reporters, press photographers, magazine writers, newsreel cameramen—would appear each morning only to be invited twice to adjourn to the air terminal Skyroom for breakfast and a wait while we hoped for the winds to subside, finally gave up and cancelled the flight. We were all happy when the third day dawned more gently.

The airplane made six successful test flights that day. Its accelerated service tests for the military at Wright Air Development Center, Ohio, set a record—170 flying hours completed in 30 days. The airplane also had the distinction of carrying in the cockpit Orville Wright on what would be his last flight.

At the end of World War II, Lockheed was in the enviable position of having a new, highly-advanced transport, thoroughly tested in military service and ready for commercial airline production. The first deliveries of an initial Model 049 actually were conversions of Air Force C-69s already in work. It took only 90 days to turn out the first commercial model, which went to TWA in November 1945.

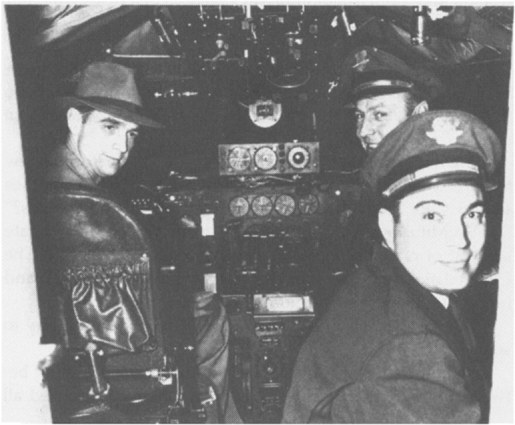

Checking blueprints of a milestone undertaking—development of the Constellation transport—with Hall Hibbard. Test flight of the aircraft with Howard Hughes, below, was to prove a terrifying experience.

There were big plans to publicize introduction of this new transport in service with TWA. Howard Hughes himself wanted to be at the controls of what would be a recordbreaking, cross-country flight carrying press and Hollywood celebrities. He earlier had established a reputation as a pilot. In fact, he was awarded the Collier Trophy for an around-the-world record flight in 1938. He flew his Model 14 at an average speed of 206 miles an hour over a 15,000-mile route in 3 days, 19 hours, and 9 minutes. We had not worked with him on that venture, although it was with a Lockheed airplane. He had the extra fuel tanks installed on his own.

Hughes would have to be checked out in the new airplane before attempting the cross-country flight, of course. So, before it was delivered to TWA, Milo Burcham, Dick Stanton as flight engineer, and I took Hughes and Jack Frye on a demonstration and indoctrination flight. Frye was just observing, but Hughes was to learn how the plane performed and how best to handle it.

Our normal procedure in checking out a new pilot in an airplane was to go through the maneuvers carefully, then have the student follow through on the controls from the copilot seat.

We had just taken off from Burbank and were only a few thousand feet over the foothills behind the plant when Hughes said to Milo: “Why don’t you show me how this thing stalls?”

So Milo lowered the flaps and gear, put on a moderate amount of power, pulled the airplane up, and stalled it. The Constellation had fine stall characteristics, not falling off, and recovering in genteel fashion.

Hughes turned to Milo and said, “Hell, that’s no way to stall. Let me do it.”

Milo turned the controls over to him. I was standing between them in the cockpit. Howard reached up, grabbed all four throttles and applied takeoff power with the flaps full down. The airplane was so lightly loaded it would practically fly on the slip stream alone. Hughes then proceeded to pull back the control all the way, as far as it would go, to stall the airplane.

Never before nor since have I seen an airspeed indicator read zero in the air. But that’s the speed we reached—zero—with a big, four-engine airplane pointed 90 degrees to the horizon and almost no airflow over any of the surfaces except what the propellers were providing. Then the airplane fell forward enough to give us some momentum. Just inertia did it, not any aerodynamic control.

At that point, I was floating against the ceiling, yelling, “Up flaps! Up flaps!” I was afraid that we’d break the flaps, since we’d got into a very steep angle when we pitched down. Or that we’d break the tail off with very high flap loads.

Milo jerked the flaps up and got the airplane under control again with about 2,000 feet between us and the hills.

I was very much concerned with Howard’s idea of how to stall a big transport.

We continued on our flight to Palmdale Airport, where we were going to practice takeoffs and landings. That whole desert area was mostly open country in those days and an ideal place for test flying.

Once on the runway, Milo and Howard exchanged seats. On takeoff from Burbank, Milo had shown Howard what the critical speeds were; so Howard now took the plane off. But he had great difficulty in keeping it on a straight course. He used so much thrust and developed so much torque that the plane kept angling closer and closer to the control tower. We circled the field without incident and came in for an acceptable landing. Then Howard decided to make additional flights, and on the next takeoff he came even closer to the control tower, with an even greater angle of yaw. He was not correcting adequately with the rudder. He made several more takeoffs and landings, each worse than the last. He was not getting any better at all, only worse. I was not only concerned for the safety of all aboard, but for the preservation of the airplane. It still belonged to us.

Jack Frye was sitting in the first row of passenger seats, and I went back to talk to him.

“Jack, this is getting damned dangerous,” I said. “What should I do?”

“Do what you think is right, Kelly,” he said. That was no great help; he didn’t want to be the one to cross Hughes.

I returned to the cockpit. What I thought was the right thing to do was to stop this. And on the sixth takeoff, which was atrocious, the most dangerous of them all, I waited until we were clear of the tower and at pattern altitude, before I said: “Milo, take this thing home.”

Hughes turned and looked at me as though I had stabbed him, then glanced at Milo.

I repeated, “Milo, take this thing home.” There was no question about who was running the airplane program. Milo got in the pilot’s seat, I took the copilot’s seat, and we flew home. Hughes was livid with rage. I had given him the ultimate insult for a pilot, indicating essentially that he couldn’t fly competently.

A small group was waiting for us at the factory to hear Hughes’s glowing report on his first flight as pilot of the Constellation. That’s not what they heard.

Robert Gross was furious with me. What did I mean, insulting our first—and best—customer? It was damned poor judgment, he said. Hibbard didn’t tell me so forcefully that I’d made a mistake, because he always considered another person’s feelings, but he definitely was unhappy and let me know it. Perhaps most angry of all was the company’s publicity manager, Bert Holloway. He had a press flight scheduled that would result in national attention, headlines in newspapers across the country and in the aviation press around the world. Because, of course, the plane would set a speed record. Would Hughes follow through as planned? By that time, I didn’t care what anyone else said. I went home and poured some White Horse and soda.

It was a frigid reception I received next day at the plant. But when I explained what the situation had been, that in my judgment I did the only thing I could to keep Hughes from crashing the plane, and then Hughes later agreed to spend a couple of days learning how to fly the plane as our pilot would demonstrate, the atmosphere thawed.

We offered a bonus to our flight crew to check Hughes out in the plane over the next weekend. Rudy Thoren, our chief flight test engineer, took my place. I never flew with Hughes again; it was mutually agreeable.

The only other time we ever thought it necessary to pay our flight crew a bonus to check out a customer’s flight crew was in training a crew who would religiously release flight controls to bow toward Mecca at certain times of the day. It happened once on approach to landing!

On his next time in the airplane, Hughes changed his attitude considerably. He followed instructions carefully. He was the only pilot I ever knew, though, who could land one of our airplanes at cruising speed! He must have made 50 or 60 practice takeoffs and landings over that weekend. In fact, he was flying right up to takeoff time for the cross-country flight.

On the flight, as he was approaching Denver, Hughes encountered a big thunderstorm that had not been predicted. Instead of flying around or over it, and perhaps adding to the flight time, he plowed right through it. Unfortunately, the passengers had not been warned of turbulence and several not strapped in their seats were injured, though not seriously.

A record transcontinental crossing was set—Los Angeles to Washington, D.C., in an elapsed time of 6 hours, 57 minutes, 51 seconds.

From then on, the “Connie,” as the plane soon came to be called, established records every time it first flew from point to point.

Except for the “penny-wise” policies of Hughes, TWA would have had a monopoly on nonstop cross-country flight for some time, because no other airliner then in service could make the flight without stopping to refuel. But in winter, against maximum headwinds, the east-to-west flight especially would take longer than nine hours. A union rule required a change of crew after that period of time. Hughes would not double-crew the flights, although it would have paid off handsomely in competitive scheduling.

Hughes had exacted an agreement from Gross in signing the Constellation fleet purchase contract that Lockheed would not sell the airplane to any other airline until TWA had received 35 of them. Despite the fact that he thereby had prevented any other line from competing with him, he refused to take full advantage of the position if it meant double-crewing. The Constellation had no competition until Douglas brought out the DC-7 with the same turbo-compound engines.

The agreement with Hughes cost Lockheed dearly. It flawed our relations with American Airlines for years. It is interesting that AA doesn’t fly a Lockheed-produced aircraft to this day, having opted for the DC-10 over the L-1011. In the commercial airplane business, everyone knows what everyone else is doing—although the information may not have been offered directly. American asked us if we could produce a new passenger transport for them, with specifications basically those of the Constellation.

Gross, Hibbard, and I met with C. R. Smith, then head of the line, Bill Littlewood, vice president and chief engineer—and a good engineer—and a few other American officials at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. We had to say that we could not build an airplane with that kind of performance although it went against the grain for all of us. And American Airlines knew damned well we were building such a plane.

American went to Douglas for the DC-6 and was responsible in large part for pushing continuing development of that plane until the DC-7 was introduced and then the jet-powered DC-8. American’s decision in the ’50s to buy hundreds of turboprop-powered Electras—it was named for the first Electra—from Lockheed effectively kept the company from being an early entrant in the jet transport field. The commanding lead that Lockheed had with the Constellation was lost.

Ironically, we may have explored the jet transport field too early. Before building the second Electra, we had invested $8 million in research and preliminary design of the Model L-199, a jet plane with four rear-mounted engines. Fuel consumption for the early engines was so high that it would require a huge airplane to fly across the ocean. Our design grew to 450,000 pounds for takeoff, and Gross decided that was just too big. Before turning thumbs down definitely, though, he retained a consulting firm for an opinion on the future of jet engines in commercial air transportation.

The report was discouraging because it forecast that operating time on the jet engine would never exceed 35 hours between overhauls. Now we think in terms of 10,000 hours.

Other orders for the Constellation followed TWA’s, and eventually the airplane flew for most of the major airlines of the world, including even American Overseas Airlines. Its identifying triple-tail and graceful lines were recognized at airports internationally.

In its long production lifetime, the design was continuously improved and extended in performance and modified for a series of specific missions. The Constellation, and then the Super Constellation, appeared in more than 20 successively advanced airline versions, cargo models, and a series of early warning, patrol, and other specialized service-types for both U.S. Air Force and Navy. Some of the commercial liners on long-range flights did have berths for sleeping passengers. The fuselage was stretched and the wings extended.

The last of the airliners, the Model 1649, still is remembered by air travelers for its luxurious interior. The planes had reclining seats with retractable footrests in standard cabin configurations. Had the turboprop engines for which this Super Constellation was designed been available, the series surely would have had an even longer life. But it could not compete with the coming jets. The last commercial Constellation was produced in 1959.

There was a myth circulating for some years that Howard Hughes had designed the Lockheed Constellation. It was not discouraged by Howard, and certainly was not true. His specifications had consisted of half a page of notes on the size, range, and carrying capacity he wanted. It was not without some encouragement from us—I did not appreciate someone else’s taking credit for our work—that eventually both Hughes and Frye acknowledged the misconception in November of 1941. They offered to publish advertisements, but Robert Gross was satisfied that their letter stated: “… to correct an impression … prevalent in the aircraft industry … the Constellation … airplane was designed, engineered and built by Lockheed.”

Hughes used to keep at least one Constellation parked on our flight line—he had one of just about every type of plane stashed away somewhere; and he would phone his favorite flight test engineer at Lockheed, Jack Real (now head of Hughes Helicopters), in the early morning hours about once a month, wanting to come over, climb into the cockpit, run up the engines, and just sit there awhile. Real would join him.

The personal eccentricities that later were to become obsessions and make a tragedy of Hughes’ life had not yet manifested themselves—at least, not to us. Hughes and Real became good friends.

While Hughes and I never again flew together, I heard from him directly during the period when he was developing his wooden Flying Boat, now a tourist attraction alongside the Queen Mary at Long Beach harbor in California.

The project actually had been proposed by Henry Kaiser, who chose wooden construction because material was plentiful while aluminum was in critical supply for war production. Hughes embraced it enthusiastically; he had the plant and people available. He took to telephoning me—I remember specifically one 8:00 a.m. call on a Sunday, because it was unusual. Hughes generally telephoned only late at night or very early in the morning. He said, “Kelly, we’re going to build a nacelle like this.… What do you think of it?” I made my comments, as I usually did, and after about two hours managed to escape and go about my own activities.

He did this on several occasions, on different subjects. Each time, I discovered, he then would call Gene Root, chief aerodynamicist at Douglas at that time, and say, “Gene, Kelly says.… What do you think?”

Then he would phone George Shairer at Boeing with “George, Kelly said … and Gene said … What do you think?” So he had a three-way consultation.

Hughes had an excellent design team on that boat, and also on his FX-11. The FX-11 he later crashed on its first flight at night over the city of Beverly Hills and was hurt quite seriously. The plane was a twin-boomed fighter-reconnaissance plane, as was the P-38. To this day, Hughes’ claim that the P-38 design was based on his FX-11 will appear in print from time to time. The FX-11 first flew in 1946. By the end of 1944, Lockheed already had built and delivered for military service some 10,000 P-38s!

The Flying Boat was a sleek design, about as good as the state of the art at the time would allow but far from being capable of carrying 750 people across the ocean efficiently and economically. It was heavier in wood than it would have been in metal, and a lot of its potential payload disappeared right there.

Hughes was determined to fly that boat to say that it had been done. Its first and only flight, with Howard at the controls, was a mismatch of common sense and responsibility. He had aboard about 32 people, not crew members but newspaper people and other guests who thought they were going for a high-speed taxi test. As he taxied down the harbor, he lifted the boat about 100 to 150 feet, and flew about a mile. If the airplane had gone out of control it would have been a tragedy. These people had not intended to go flying, particularly on a first flight.

While this determination to prove himself in aviation sometimes led to seemingly heedless action, it also spurred him to seek a forward-looking passenger transport for his airline—a decision from which air travelers all over the world would benefit in safer, faster, and more enjoyable flying. Hughes deserves credit for that. And his commitment to purchase the advanced airliner that became the Connie put Lockheed into the big time of commercial aviation.

What the Constellation was to air passenger traffic, the C-130 Hercules later was to the air-cargo business. Introduced as a military plane, it was the first design specifically for that purpose. During World War II and after, bombers or troop carriers had been converted for cargo. It was the first transport designed from the drawing board up to take advantage of new turboprop engines—jet engines driving propellers. They promised speeds of 300 to 500 miles per hour at altitudes to 45,000 feet.

With the engines and its special design, the C-130 was a major development in cargo aircraft. It would fly higher and faster and more economically than existing military transports and was tremendously versatile.

The fuselage was so low—only 45 inches from the ground—that loading was easy under any conditions. A section of the aft fuselage dropped down to become a loading ramp. The airplane converted easily and quickly from personnel carrier to hospital ship, from flying a load of heavy machinery to dropping paratroopers.

It was designed to land and take off from short and rough runways. It even operated from a carrier in a demonstration of performance. The plane was designed in what was to be known as Lockheed’s “Skunk Works” but assigned to Lockheed’s Georgia company for production. Later commercial versions were developed there. The plane has been a workhorse around the world. Many of its most effective features later were adapted to the much larger C-5A, designed at the Lockheed-Georgia Company.