APPROACHING THE HELLENISTIC POLIS THROUGH MODERN POLITICAL THEORY: THE PUBLIC SPHERE, PLURALISM AND PROSPERITY

Benjamin Gray

1 THE HELLENISTIC POLIS AND CONTEMPORARY METHODS IN THE STUDY OF POLITICS AND POLITICAL THOUGHT

Modern political and social theory have long stood in a fruitful, mutually reinforcing relationship with historical study of the Greek polis and its political thought.1 This relationship has been rooted in theoretical and historical study of the city of Athens, as a paradigmatic and problematic democracy, especially during its classical period of imperial and cultural flourishing (c. 478–322 BCE). Greek historians interested in contemporary social and political theory, and contemporary theorists interested in the Greek polis, have tended to dedicate less attention to other Greek cities, and to other periods in the history of the Greek polis. There has been relatively little focus, for example, on the subsequent Hellenistic period (c. 323–31 BCE), from the death of Alexander the Great to the establishment of the Roman principate.

Although leading philosophies of the Hellenistic period, especially Stoicism and Epicureanism, have played an important role in discussions of ancient and modern ethics and sociology,2 the Hellenistic city itself has not figured so prominently in those debates. This is partly because the Hellenistic polis was long regarded as a poor, emasculated and depoliticised shadow of the classical polis, especially of imperial Athens. Hellenistic shadow-poleis were seen as eclipsed by the much more expansive Hellenistic kingdoms and their courts, and then by the developing Roman Empire. This disparaging assessment has been dispelled by recent decades of Hellenistic scholarship, which have demonstrated the vitality and range of Hellenistic civic life, institutions and thought: far from ‘dying at Chaironeia’, the Greek polis remained a dominant social, cultural and political form, which helped to shape the ever more interconnected Mediterranean of the Hellenistic kingdoms and then the Roman Empire.3 This has now prompted innovative contributions which have sought to bring the Hellenistic polis into the ongoing contemporary debate about the Greek city and modern citizenship.4

In this chapter, I focus on one way in which study of the Hellenistic polis can harness methods and approaches of contemporary political and social theory. My argument is that the rich record of inscribed documents from the Hellenistic cities, ranging from private gravestones to public laws and decrees, makes it possible to apply contemporary approaches to the study of political thought and debate which stress the complexity and breadth of the public sphere, especially the two-way interaction between intellectual theory building and even the most everyday political assumptions and rhetoric. Indeed, comparison of the epigraphic, literary and philosophical sources for the Hellenistic polis makes it possible to reconstruct a complex, dynamic Hellenistic public sphere of debate about power, principles and community, within and across cities, involving many more participants than a handful of great Stoics and Epicureans.5 Not only was there such a thing as Hellenistic political philosophy, as scholars have emphasised in the last thirty years,6 but that sophisticated political theorising was itself stimulated by much broader political debates. Both the form and content of the Hellenistic public sphere reconstructed through these methods can in turn offer historical parallels for attempts in modern political thought to adapt traditional notions of citizenship, participation and civic equality to respond to a more cosmopolitan, mobile world, marked by severe inequalities of wealth and power.

The past few decades of scholarship on classical Athenian political thought have demonstrated the value of an inclusive, dynamic conception of ancient Greek political thinking. Nicole Loraux, Josiah Ober, Paul Cartledge, Danielle Allen, Ryan Balot and several others have revealed the advantages of situating the great works of political theory of Plato and Aristotle within the broader classical Athenian debates about citizenship, democracy and virtue which can be reconstructed from Athenian oratory, drama and historiography.7 Others, such as Peter Liddel, have further demonstrated how the official civic rhetoric of classical Athenian inscriptions can be used to further enrich this picture of a thriving and disputatious Athenian public sphere, with which political philosophers engaged.8

Many of these approaches to classical Athenian political thought take their theoretical inspiration partly from the work of the Cambridge School of the contextualist study of political thought, especially the work of Quentin Skinner.9 Guided by that example, these Greek historians have interpreted Plato, Aristotle and other Athenian intellectuals as performing distinctive speech acts in their work, designed to contribute to, and shape, the political and theoretical debates and language of their society.10 According to this approach, the meaning of Plato’s Republic and Aristotle’s Politics can be fully understood only with the aid of a thorough and nuanced understanding of the wider linguistic and discursive context in which those works were produced, which can enable historians to reconstruct what the authors were doing – what speech acts they were performing – in writing and arguing as they did. In other words, Plato and Aristotle, like Skinner’s Machiavelli, were eloquent participants in a complex contemporary discussion, in their case about the politics and psychology of democracy, whose broader contours must be integral to any effective interpretation of their ideas.

The question of what constitutes essential ‘context’ for the understanding of major works of political thought is crucial for this method. Historians of modern political thought working in the Cambridge School tradition have often concentrated primarily on the intellectual context.11 This is the context attested in the works of the well-known thinkers’ less prominent, but equally intellectual and systematic contemporaries: often self-consciously theoretical or educational speeches, pamphlets or tracts, such as those which circulated at the time of the English Civil War and Commonwealth, provoking responses from (among others) Hobbes.12 Plato and Aristotle were certainly operating within a dynamic intellectual context like this, but that context is very hard to recover because of the loss of the work of, for example, most of the Sophists. The modern historians of the Athenian democracy mentioned above have compensated well for this problem by placing the theoretical political arguments of Plato and Aristotle alongside, for example, those of non-philosophical authors whose works have survived because they were judged pre-eminent in their own separate fields, especially Thucydides and Xenophon in historiography and Isocrates and Demosthenes in rhetoric. These ancient historians have, however, also compensated for this source problem by broadening out the notion of context to include, as part of the Athenian conversation about political principles, not only intellectual reflection but also less systematic and theoretical comments, including the more pragmatic, everyday or even throwaway remarks found in historiography, oratory and epigraphy. The Hellenistic period offers rich evidence and debates highly suitable for the extension of this dimension of their approach.

In developing further this particularly inclusive approach to ancient political thought, it is possible to supplement the theoretical example of the Cambridge School with the methods and approaches developed by two other modern historians of political ideas strongly influenced by contemporary social science. Both E. P. Thompson, in the British tradition, and Pierre Rosanvallon, in the French, offer distinctively inclusive and broad-ranging conceptions of what counts as a contribution to collective, community-defining debates about basic political questions of virtue, justice and community. Both historians are partly inspired by their own direct experience of workers’ education and experiments in radical worker democracy, but also by social scientists’ discussions of the public sphere, political culture, discourse and ideology. Thompson argued for the complexity and depth of the political consciousness of an English working class which was ‘present at its own making’; its members reflected deeply about their own experiences before and during the Industrial Revolution, through popular sermons, tracts, songs and conversations.13

Rosanvallon, for his part, has developed a more theoretical rationale for including the broadest possible range of evidence within the history of political thought and debates. He argues for a ‘philosophical history of the political’, which requires analysing a very wide range of acts, habits and apparently throwaway statements with the same interpretative care as formal theoretical tracts. These varied examples of social interaction and language should be interpreted not purely as expressions of power or domination, but also (often at the same time) as contributions to building, sustaining and questioning a fruitful shared world of political concepts, problems, ambiguities and understandings.14 As Rosanvallon himself puts it:

the subject matter of the philosophical history of the political, which I would call ‘conceptual’, cannot be limited to the analysis of and commentary on great works, even if these can often justifiably be considered ‘moments’ crystallizing the questions that an era poses and the responses that it attempts to these questions. The history of the political borrows, especially, from the history of mentalities the concern of incorporating the totality of the elements that compose that complex object that a political culture is: the way that great theoretical texts are read, the reception of literary works, the analysis of the press and movements of opinion, the life of pamphlets, the construction of transitory discourses, the presence of images, the significance of rites, and even the ephemeral trace of songs. Theorizing the political and doing a living history of representations of life in common combine in this approach. For it is at a ‘bastard’ level that one must always come to the political, in the tangle of practices and representations.15

Obviously not all of the modern paraphernalia of politics and culture named by Rosanvallon have ancient equivalents which are accessible to the ancient Greek historian. Nonetheless, the rich variety of Hellenistic inscriptions, public and private, offers an extremely promising seam of parallel, though different, evidence for the ancient Greek world.16 The rhetoric of those inscriptions can be used to reconstruct the very wide-ranging political discussions and tensions17 which provoked contributions or reactions from Hellenistic intellectuals writing on politics – for example, philosophers such as Epicurus or the Stoic Chrysippus or historians such as Polybius. Indeed, applying careful ideological and theoretical analysis even to apparently routine or mundane Hellenistic inscriptions, treated as themselves often intricate contributions to collective self-understanding, can make it possible to write a Thompson-style history of Hellenistic political thinking beyond the narrowest intellectual and political elite, or the Hellenistic chapter of Rosanvallon’s ‘philosophical history of the political’. The aim is to reconstruct the complex ‘Hellenistic moral economy’ of interconnected debates, concepts and ideals.18 That ‘moral economy’19 was just as complex, and deserving of intricate study, as recent studies have shown the Hellenistic (material) economy to have been.20

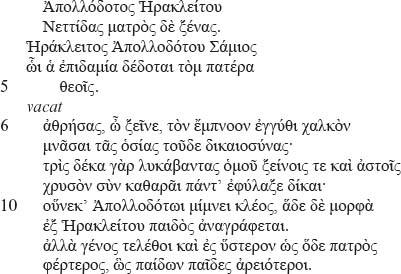

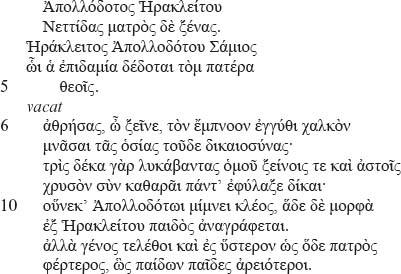

The rest of this chapter offers examples of the potential of this approach, focusing on the rich political rhetoric of the public inscriptions of Hellenistic poleis, containing the published versions of their laws and decrees. To give an immediate impression of the usefulness of the full range of Hellenistic inscriptions for building an inclusive, complex picture of Hellenistic political thought, it is worth analysing a concrete example of a more private inscription, still published in a civic context: the inscription on a Hellenistic family honorific monument on Rhodes.21 That inscription presents a complex family history, and interweaves it with ethical values. The grandfather, Herakleitos, son of Pausanias, had been an active Rhodian citizen. He had a son, Apollodotos, by a non-Rhodian mother. This complicated Apollodotos’ civic status on Rhodes, forcing him to present himself as ‘of the deme of Nettidai, but of a foreign mother’. This Apollodotos put up a statue of his father with an accompanying inscription, the first preserved on this monument (col. I). The inscription praises his father for his service as a magistrate (phylarch) of the Ialysian phylê (civic subdivision) on Rhodes, as well as his victories in ‘fitness’ or ‘manliness’ (euandria) and the torch-race at festivals. From his position on the margins of Rhodian citizenship, Apollodotos thus placed the emphasis squarely on traditional, institutionalised civic engagement within the contours of the home polis.

Alongside that expression of traditional civic commitment, in the other inscription on the monument (col. II), Apollodotos’ own son, Herakleitos, developed an alternative picture of virtue, which allowed more dignity for Apollodotos’ own interstitial lifestyle. To accompany a statue of Apollodotos, his son Herakleitos published the following inscription and epigram:

Apollodotos son of Herakleitos, of the deme of Nettidai, but of a foreign mother. Herakleitos, the son of Apollodotos, a Samian to whom residence rights have been given, dedicated this statue of his father to the gods.

‘Stranger, having gazed at the living bronze close at hand, remember the holy justice of this man. For thirty years he guarded all gold with pure justice for both foreigners and citizens alike. As a result glory remains with Apollodotos, and this likeness is set up in public by his son Herakleitos. But may the family continue to exist, and in the future, just as this man was better than his father, may the children of his children be stronger still.’

Herakleitos identified himself as a citizen of another island polis, Samos, where he must have gained citizenship, now living on Rhodes by virtue of a grant of residence rights (epidamia): he combined civic identity and pride with a recognition of his own mobility and complex status. It is the epigram which explicitly offers a more open, cosmopolitan vision of virtue. Apollodotos, even though not a full citizen of his host city, had exercised ‘holy justice’ and ‘pure justice’ there for thirty years, demonstrating the attributes – financial incorruptibility and punctilious respect for agreements – required of a just banker. Moreover, he had done so in relations with foreigners and locals alike: his justice had a universalist cast, making no distinctions by status or origin. This quite simple and routine private inscription therefore contains complex, idealistic language about pure justice, adapted to suit this family’s particular circumstances. Its approach to justice is consistent with the religious component of the statue monument, dedicated to ‘the gods’, but its abstraction also evokes an almost Platonising conception of transcendent ethical values. Read as a whole, the monument also reveals sophisticated reflection and dialogue about the meaning of citizenship, virtue and justice in a more cosmopolitan world: the younger Herakleitos’ inscription responds to his father’s proudly civic inscription by portraying more unconventional, border-crossing forms of justice and social responsibility.

In doing so, Herakleitos was engaging in a much broader Hellenistic conversation about trans-polis relationships and ethics, and their implications for civic identity itself. Integrating voices such as Herakleitos’ can help to make our understanding of that broader conversation much more sophisticated. For example, it casts in a different light the scepticism about the traditional polis and traditional civic engagement of many leading Hellenistic philosophers: in particular, Stoic thinkers, who tended to present the wise man as a citizen primarily of a natural world polis (‘cosmopolis’) of fellow wise men, rather than of his particular polis, to which he is attached only by an accident of birth;22 and Epicureans, who advocated semi-detachment from the political realm, in favour of a focus on pleasurable, reliable relationships within smaller friendship groups.23

These developments in philosophical ethics need not be seen as straightforward expressions of a new, homogeneous Hellenistic Zeitgeist, more individualistic and cosmopolitan, with a focus on large kingdoms rather than small city-states. On the contrary, they can be seen as contributions to a varied public sphere still built on civic institutions and values. On the one hand, such philosophies captured and refined the anxieties and aspirations of those, such as Apollodotos and the younger Herakleitos on Rhodes, who lived an interstitial life on the margins of Hellenistic civic life, outside normal citizenship but still aware of its attractions: Stoic and Epicurean ideas must have had great appeal for those who sought new forms of community, virtue and knowledge which could be just as fulfilling as the traditional civic lifestyle, or even eclipse it.

On the other hand, Stoics and Epicureans can also be seen as in direct dialogue with established citizens of poleis, still suffused with civic pride. Whether based in cities or at royal courts, Stoics and Epicureans would have constantly come into contact with continuing devotees of the civic ideal. In response, they provided the essential quasi-Socratic challenge and provocation to civic ideology and practice which were necessary for the continuing vitality of the polis and its public sphere. As Ober argued, the Athenian democracy flourished partly precisely because it harboured, and gave voice to, strenuous critics of the Athenian consensus that democracy was the most justified and desirable political system: a critical community which strengthened democracy by questioning it at its roots.24 In the early Hellenistic period, as Ma has recently argued, there emerged a new consensus, more broadly shared around the Greek world: a ‘great convergence’ of cities in their values and institutions, towards a shared model of civic participation and city autonomy, negotiated through interaction with kings. This model had striking similarities with Aristotle’s ideal model of balanced politeia, though often called dêmokratia by Hellenistic Greeks themselves.25 The city decrees explored in the rest of this chapter, and also in Canevaro’s chapter in this volume, offer vivid evidence of the working of this new consensus in practice.

This new consensus meant that the obvious new focus for the critical community of intellectuals and philosophers – the obvious, taken-for-granted ideal needing to be probed in a rigorous and useful critique – was now the very ideal of the law-governed polis itself, and its claim to centrality in the good human life. Stoic and Epicurean attacks on the polis can thus be regarded as much-needed internal critique, rigorous and uncompromising, of a still flourishing system. As Long argues, even if some Hellenistic philosophers turned away from traditional citizenship and the traditional concern of Greek political philosophy with the analysis of constitutions, their arguments were still deeply political in a broader sense: they were concerned with society’s structures as well as individual lives, and tried to envisage alternatives to the polis. Indeed, they advocated a ‘reconstitution of the socio-political world’, which could be achieved if everyone embraced their demanding and unconventional ethical advice, based on the Socratic ideal of self-mastery.26 Relevant philosophers borrowed from live civic models in order to attack them, not only in imagining alternative communities such as the cosmopolis, but also in building up their pictures of individual flourishing: as Long puts it, ‘Hellenistic ethics transfers to the self traditional notions of leadership and political control’,27 making individualistic metaphors out of central polis principles of law-governed rule, freedom and autonomy. In doing so, these philosophers laid down a challenge for the citizens of Greek poleis: to restate and reimagine the value of the traditional polis and traditional citizenship in the new world. Engaged Hellenistic citizens responded to that challenge with confidence and subtlety, further reinforcing the Hellenistic public sphere; their efforts are the subject of the rest of this chapter.

2 THE HELLENISTIC POLIS AND THE SEARCH FOR OPEN CITIZENSHIP

Although the Greek polis has remained an indispensable point of reference in contemporary political thought, it has suffered vigorous criticism as a political model. Suspicion of the totalising, illiberal character of ancient citizenship dates back, at least, to debates about the ethics and politics of the French Revolution: the Greek polis came under suspicion, for example in the work of Benjamin Constant, on the grounds that it relied on ideals of fanatical devotion to, and self-sacrifice for, the political community, incompatible with modern values of personal freedom and constitutional protection of individual rights.28

This attack was intensified at the time of twentieth-century European totalitarian regimes, perhaps most cuttingly in Karl Popper’s attack on Plato’s polis in The Open Society and its Enemies (1945). Hannah Arendt drew an influential distinction between the abstract, anti-pluralist Plato and the truly political public sphere of the classical democratic polis, which she saw as a space for free and equal interaction between contrasting voices.29 Nonetheless, suspicion has grown that the classical Greek polis was, even in practice, a disturbingly closed and anti-pluralist form of society, with too little space for individual difference and outsiders. Arendt’s own strong privileging of ‘action’ in the public political sphere of the polis over the more mundane ‘work’ and ‘labour’ of private, social and economic life may well itself have fed such suspicions.

Wariness about the closed polis has paradoxically come to unify the otherwise very different Anglo-American liberal30 and Continental post-structuralist traditions:31 they share a suspicion of classically inspired notions of community and the public good which appear to offer the possibility of transcending conflict and difference through education and public virtue. Developing this approach, other modern thinkers have criticised the exclusive patriotism which they see as inherent in the ancient civic ideal: a legacy which modern forms of cosmopolitanism have to overcome, or at least supplement.32

It is important not to exaggerate the flaws of the classical Greek polis or Athenian democracy, or to judge them only against impossibly demanding modern moral ideals. Moreover, there has been a recent tendency among some classicists and political theorists to resist the disparaging, exclusive picture of the classical polis and its political thought, in favour of models emphasising greater openness and ambiguity.33 Nonetheless, it is not difficult to see why even democratic classical Athens might have proved less than appealing to contemporary political theorists who highly prize cosmopolitanism and pluralism: that is, those who advocate complex, law-governed political interaction, based on peaceful deliberation about alternative viewpoints, among a wide spectrum of different people.

Classical Athenian citizenship was quite literally ‘closed’ to most outsiders, a feature symbolised by Pericles’ citizenship law (see Lyttkens and Gerding, this volume). Even if, as some scholars have recently emphasised, Athenian citizens and resident foreigners often in practice managed to sidestep institutional and ideological constraints in their everyday interactions,34 the ideal of the closed Athenian descentgroup was still a powerful influence on Athenian civic life. As Loraux argued, the Athenian citizen body nourished ideals of masculinity and ethnic purity, symbolised in the myth of autochthony, which reflected and reinforced the problematic character of its collective relations with women and resident foreigners, let alone slaves.35 This brand of exclusivity and assertive masculinity was the internal correlate of a hostile foreign policy, based on almost perpetual military engagement. That hostility was a response to a harsh environment of competing claims to hegemony, which demanded vigilance, but the Athenians developed and sustained their own complex structures of imperial and hegemonic control. The democracy had a thriving cultural life; it also created spaces, especially its dramatic festivals, for internal critique and reflection.36 Nevertheless, relations between the dêmos and freethinking intellectual critics were often tense. The condemnation of Socrates, perceived by some at the time as a way of defending the purity and strength of the polis and its laws,37 became a symbol of the conflict.

The problematic features of the classical Greek civic model have prompted some to call for modern classicists and political theorists to develop new versions of the ‘Aristotelian’ civic ideal, better suited to accommodating individual difference and ethical disagreement.38 Although this is often conceived as a thoroughly modern project, certain developments in the Hellenistic polis and its public sphere can offer helpful starting points for reflection. This is certainly not to say that the Hellenistic poleis represented some kind of utopia. Indeed, they preserved many of the problematic features detailed above. The early Hellenistic polis, in particular, was conservative in institutions and ideology, perpetuating many fourth-century patterns. Nonetheless, in the course of the Hellenistic period, Greek cities experimented with new models of citizenship, which may have something to offer to modern thinkers interested in more ‘open’ or even ‘ambiguous’39 forms of citizenship: they suggest possible routes towards more flexible, inclusive and pluralistic types of public sphere.40 This emerges strongly when, as here, Hellenistic political thought and debates are interpreted in the broadest possible way, to include the institutions and rhetoric attested in civic inscriptions.

The most striking institutional changes in the Hellenistic civic world pointed in this direction. For one thing, many more poleis came in the Hellenistic period to participate meaningfully in larger political units, with institutions and rules designed to achieve fair cooperation across polis borders. These ranged from unions or sympoliteiai between two distinct communities41 to larger and more complex federal structures such as the Achaian and Aitolian Leagues.42 These developments created a new form of institutionalised cross-border public sphere, such as the pan-Peloponnesian public sphere celebrated by Polybius.43 They were also connected with broader changes in the tenor also of looser inter-polis relations, away from competing attempts at hegemony and towards more egalitarian ‘peer-polity interaction’ among mutually respectful city-republics, aided by increasingly complex forms of interstate diplomacy and arbitration.44 War remained ever present, but it was in the Hellenistic world that the Greek cities experimented with what might be called ‘post-imperial’, if not ‘post-colonial’, approaches to foreign policy, as they subtly negotiated their reciprocal positions among themselves and their collective standing vis-à-vis the martial Hellenistic kingdoms and Roman Empire.

Most importantly for the purposes of this chapter, these interstate changes ran in parallel with developments in the shape of individual poleis and their public spheres. It became much easier for outsiders, including those without a long Greek ancestry, to participate in polis life, whether in a newly founded Hellenistic polis (especially in Asia Minor) or in a long-established polis which had become more open to outsiders. Partly because of federalism, double or even multiple citizenship became more common, and accepted, across the Greek world by the later Hellenistic period.45 Even if the mobile wealthy were the main beneficiaries of this development, a broader spectrum of the population could participate in another development which rendered many poleis’ public spheres more open and complex: the explosion in the Hellenistic world of voluntary associations or koina, usually devoted to a particular cult and often united by practice of a craft or other shared interest. Although many such associations catered for expatriates with a shared ethnic origin, others were much more mixed in membership, combining local citizens with outsiders. Most such associations had their own quasi-civic institutions, including an assembly and magistrates, which opened up the possibility of formal participation in the public sphere to many who would otherwise have been excluded from it.46 Indeed, these associations made it possible for those with common or overlapping interests and concerns, from worshippers of Egyptian Isis at late Hellenistic Athens47 to caravandrivers at Palmyra in the Roman Empire,48 to negotiate their similarities and differences through flexible but still formal channels, even in the absence of pre-existing political or institutional bonds.

By the later Hellenistic period, after c. 150 BCE, these changes in the form of the Greek public sphere came to influence the ways in which the whole sovereign dêmos or civic community of a polis could be conceived and enacted.49 Indeed, in that period, it is possible to detect strong echoes of the poleis’ contribution to the dialogue about civic patriotism and cosmopolitanism identified at the end of the last section; poleis’ citizens sought to combine the two, conceptualising the whole civic community as something like a macrocosm of a koinon or association, flexible and open yet also structured and civic. This can be illustrated through some inscriptions from the city of Priene in Western Asia Minor, which had flourished in the early Hellenistic period as the archetype of the small-scale, planned, self-contained, democratic Hellenistic polis. Later Hellenistic Prienian experiments with more open styles of civic community are attested in some of the long Prienian honorary decrees of that period, passed in praise of its leading citizen benefactors.

Some time in the first century BCE, the Prienians passed three successive decrees praising a certain Aulus Aemilius Zosimos for his extensive civic contributions, especially as gymnasiarch (the magistrate in charge of the gymnasium). Zosimos is a good example of the normalisation of naturalisation, and of double citizenship, at this point. The Prienians appear earlier to have been very reluctant to open their citizenship to outsiders who would actively exercise it.50 By contrast, Zosimos was not only permitted to play a leading role in civic life, but also explicitly presented as a foreigner and Roman citizen who had been naturalised as a citizen of Priene. The opening of the first decree for him even celebrated his complex identity and loyalties, praising him for loving Priene as if it were his fatherland, showing the civic concern which would be expected of a genuine citizen.51 His precise circumstances are unclear, but he was perhaps an Italian immigrant or freedman of a Roman citizen.52

The opening of that first decree also offers a complex picture of the broader Prienian civic community with which Zosimos engaged. It emphasises that he helped and served many different members of the community: as the decree puts it, he knew that virtue alone brings the greatest fruits and gratitude from citizens (astoi) and probably also foreigners who hold ‘the fine’ (to kalon) in honour.53 This description of the community sounds like a deliberate attempt to broaden, loosen and re-energise notions of the polis and citizenship, in a way which took account of new forms of social mobility and complexity: the Prienian polis was now treated as a broad community of people devoted, not to particular gods, land or traditions, but to an abstract ethical standard of to kalon, which foreigners such as Zosimos could appreciate as keenly as Prienians.

This newly flexible, heterogeneous community could incorporate all the interdependent residents of the city, whose fortunes were interlinked regardless of origin and legal status. Indeed, a slightly earlier Prienian decree describes the community towards which another benefactor, Athenopolis, directs his attention as ‘those conducting their lives together’ with him, hoi synanastrephomenoi, an unusual word which seems specifically designed to evoke interdependence across a broad spectrum.54 Similarly, another late Hellenistic Prienian decree refers to a benefactor’s good service towards ‘those living together’ with him through kinship or acquaintance, hoi symbiountes, as well as the rest of the citizens.55 This notion of symbiôsis, which was also often used in the Roman imperial period to describe fellow members of a voluntary association,56 explicitly evokes a form of shared life deriving more from overlapping fortunes than from ethnic or institutionalised homogeneity.

Despite its breadth and openness, the flexible Prienian civic community envisaged in these decrees was still strongly civic. It was still expected to carry out traditional civic activities, such as recognising virtue and honouring benefactors. Moreover, the Zosimos decree’s picture of citizens and foreigners united in shared commitment to ‘the fine’ (to kalon) recalls very closely the citizens of Aristotle’s ideal polis, who are united by their commitment to ‘living well’, rather than merely living.57 The Zosimos inscriptions lend themselves, therefore, to the modern project, discussed above, of devising a more open Aristotelianism. The late Hellenistic Prienians were bringing into the centre of their civic life and self-image the kinds of status-crossing, open forms of community and citizenship58 with which citizens and thinkers had experimented on the margins of classical civic life and thought.59 This must have partly been an automatic change of perspective in response to altered social realities, as in some modern states,60 but it also pointed towards the kind of subtle blending of particular and universal ideals advocated by some modern theorists.61

At the same time, this change offers a historical case study for testing critical modern theories which see advocacy of ethical and political universalism as a form of concealed imperialism or hegemony, which itself submerges or blocks political disagreement and true pluralism.62 This issue of power relations – or their concealment – in cosmopolitan discourse is undoubtedly a complex and double-edged one. It is noteworthy that Zosimos, himself quite possibly a former slave or descendant of slaves, was held to have extended his open benevolence even to slaves: he made his first day in office as stephanêphoros ‘common for all on equal terms’, inviting even slaves and foreigners to the ‘humane benefaction’ (philanthrôpia) of breakfast at his house. This briefly rendered of the least importance the formal status of foreigners and the ‘chance fate’ (tychê) of slaves.63 Although this was only a temporary suspension of status distinctions, which might even have helped to reinforce the whole status edifice, the suggestion that slave status was a matter of ‘chance’ was at the same time a bold challenge to any notion of a fixed or ‘natural’ distinction between free and slave, citizen and outsider. This is especially striking in a group of inscriptions for a benefactor which in other places, as noted above, chime closely with Aristotle’s Politics and ethical works, which insist strongly on the natural character of status distinctions.

The ideal of humanity (philanthrôpia) mentioned here, increasingly attributed to home citizens in the later Hellenistic period, combined an element of cosmopolitanism with a related dimension, also worthy of further study by modern thinkers seeking to imagine a more open polis: it evoked the cultural, gentle and reflective virtues which came to occupy a more central place in the image of the good citizen, as military virtues receded slightly in importance.64 For example, Zosimos was praised for organising a literary tutor for the ephebes in the gymnasium of Priene, to lead their souls towards ‘humane emotion’ (pathos anthrôpinon), at the same time as physical training primed their bodies.65 Zosimos was certainly not alone in being celebrated for making cultural contributions central to his leading civic role: as L. Robert put it, the gymnasium became effectively a ‘second agora’.66

The gentle, humane and cultured virtues encouraged and scrutinised in this changing public sphere, such as philanthrôpia, were, unlike militaristic patriotism, virtues in which many different residents could excel: not only male foreigners and visitors, but also women, who are increasingly attested playing a leading civic role, as the prominent second-century BCE female benefactor and magistrate Archippe of Kyme did.67 Women’s public visibility remained in many ways strongly curtailed. Moreover, those elite women who did play significant roles were often standing in as representatives of their household, in the absence of a suitable male representative. Nonetheless, their very prominence must in itself have significantly reshaped the civic public sphere.68

The developing discursive form and content of the civic public sphere also made possible new types of openness to diverse approaches and choices of life, and even something resembling pluralism, or a politics of recognition. Honorary decrees, such as those for Zosimos discussed above, became much subtler in their discussion of the psychology and aspirations of benefactors, stressing these citizens’ voluntary choice or voluntary disposition (prohairesis) to engage in their polis.69 As I discuss in more detail elsewhere, the word prohairesis evoked conscious, reflective choice; it was also, for example, used to describe affiliation to one of the varied Hellenistic philosophical schools.70 A late Hellenistic polis could even openly embrace the plurality of philosophical prohaireseis open to its citizens. When the Athenians sent their famous ‘philosophers’ embassy’ to Rome in 155, they sent leading philosophers from no fewer than three competing schools – the Stoics, Academics and Peripatetics – to plead their case and advertise Athens’ intellectual prowess.71 This pluralism was probably also reflected in the formal educational curriculum. In the later second century BCE, the official ephebic curriculum, authorised by the polis and celebrated in an honorary decree for ephebes, could include teaching held in different philosophical schools, the Academy, Ptolemaion and Lyceum.72 Even if these varied locations were chosen partly for pragmatic reasons of space, with philosophers of different schools moving between buildings,73 there would have been a powerful symbolism in Athens, the polis which had once condemned Socrates, encouraging its young citizens to spend time learning and reflecting in turn at the physical centres of contrasting critical traditions. To develop a reflective approach to vexing philosophical questions was now central to being a good citizen; something like D. Villa’s modern ideal of ‘Socratic citizenship’, at once moral, intellectual and civic, came into view.74

3 THE ENDURANCE AND ADAPTATION OF POLITICS IN THE HELLENISTIC POLIS

An obvious and important objection to my argument so far is that whatever moves the Hellenistic poleis made towards greater openness, inclusivity, peaceableness, gentleness and pluralism in their public sphere were achieved at too high a cost. According to this objection, the Hellenistic cosmopolitan and cultural turn simply helped civic elites, and wider Mediterranean elites, to avoid rigorous scrutiny. The argument would be that Hellenistic changes diverted attention away from material questions of production and distribution, in favour of more nebulous questions of recognition and education, which had less direct impact on inequalities of wealth and status. Moreover, according to this objection, Hellenistic developments hindered collective action and regulation by the citizenry, because civic communities were now so mixed, fluid and polycentric. According to this view, checks and balances inherited from the classical polis lost their egalitarian bite without the driving force of a homogeneous citizen body, unified, mobilised and committed to equality as a result of collective military action and experience. The slackening of that kind of mobilisation might also be thought to have rendered cities less capable of defending themselves against outside interference or even dominance. Some might even argue that more open citizenship was already itself a symptom of the abandonment of civic autonomy: citizens lost interest in jealously guarding access to citizenship, because the vote became much less valuable in emasculated cities with a dwindling geopolitical role.

Doubts such as these perhaps partly explain why historians’ very effective defences of the vitality of the Hellenistic polis in recent decades have tended to focus on the persistence of democratic civic institutions, laws and practices of scrutiny familiar from the classical period.75 Distinctive Hellenistic developments, from cosmopolitanism to the increasingly elaborate honorific systems of Hellenistic poleis, have been treated as much more problematic. It is precisely the long, intricate, highly rhetorical decrees of the later Hellenistic period, such as the Prienian decrees for Zosimos discussed in the previous section, which are identified as the most embarrassing sign of the dilution of civic equality and democracy. It is not hard to see why such decrees might lend themselves to a pessimistic reading: they appear to abandon civic equality in favour of fulsome praise for the great men (and women) of increasingly narrow civic elites. They even appear to help to build for those elite figures a dominating civic profile, which ranges far beyond the traditional limits of the exercise of temporary, rotating magistracies in turn.76

According to this reading, these decrees are a sign that civic institutions were being diverted into giving a moral veneer to ostentatious philanthropy, allowing vacuous77 language about individual souls and cultural ideals to encroach on genuine scrutiny and strong assertion of the common good. This pessimistic picture of (later) Hellenistic civic life coalesces with the ‘post-political’ dystopia of some contemporary critical theory. Decrees’ rhetoric emerges as an ancient version of what C. Mouffe calls ‘politics in the register of morality’, which she sees as dominant in post-Cold War liberal democracies: the use of moral language, focusing on the self and personal conduct, in order to smooth over inequalities of power and wealth, blocking out genuinely political, agonistic debate about conflicting interests.78

Research is ongoing, but it may well be true that many Greek cities assigned greater power to their elites at least in the later Hellenistic period, moving towards something closer to a ‘mixed constitution’. Nonetheless, even if that turns out to be the most plausible picture, this would not be a story only of the erosion of opportunities for wide political participation: even if poorer male citizens lost some of their bargaining power in many cities, women and foreigners participated in the civic public sphere to an unprecedented degree. Moreover, even if cities lost some of their independence from outside interference, coming to rely on subtle negotiation with superiors rather than defiant self-assertion, that was partly compensated for by gains in different kinds of freedom: the freedoms for self-realisation and cultural exchange made possible by the more peace-oriented civic life and public sphere explored in the previous section.

Most importantly, that new style of civic public sphere need not be regarded as a pale shadow of its highly politicised classical predecessor, newly open and inclusive because the stakes had now become much lower. That would be to underestimate the vibrancy of the civic and associative life documented in post-classical inscriptions, which engaged the energies and enthusiasms of both non-citizens and citizens themselves for centuries. It would also be to underestimate the continuing political character of the discourse of the Hellenistic cities, even the ubiquitous discourse about honours: debates in the assembly and wider polis about whom to honour as benefactors, and how, were themselves a central forum for debate and negotiation concerning both politics and ethics, a distinctive space for discussion of both power and the good life.79

The political complexity of the Hellenistic honorific process can be illustrated by analysing the resulting honorific decrees as subtle and mixed speech acts, crystallising the many different speech acts which contributed to their creation. John Ma has shown how modern speech-act theory can bring out the dynamic, power-political dimension of the honorific process.80 When honours were to be discussed, an elite figure, or his supporters, laid claim in the assembly and wider public sphere to civic prominence and authority in recognition of past and potential contributions to civic life. As Ma emphasises, the dêmos then responded with its own speech act: it authorised honours, but simultaneously emphasised through its collective voice that this reciprocal relationship was conditional on the continuing willingness of elite figures to recognise and accommodate the people’s will and interests. The honouring dêmos’ distinctive speech act – its use of complex rhetoric to achieve practical ends in the world – served to create and publicise demanding, long-term expectations of civic commitment and fairness on the part of elites, whether kings or local citizens. Indeed, the dêmos’ collective speech acts were then immortalised in honorary decrees or inscriptions on statue-bases, which cast the honoured benefactor as inextricably enmeshed in the civic community, perhaps even dependent on its approval. Whenever a polis put up a statue-base with the honorand’s name in the accusative case, it signalled that the honorand was as much acted upon as agent, in a complex relationship with the polis.81

Ma’s picture of the power-political charge of the Hellenistic honorific process builds on, and develops, many of the insights of Ober’s Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens, discussed and updated also by Carugati and Weingast in this volume. The Hellenistic cities perpetuated a central part of classical Athenian political discourse, emphasised by Ober: negotiation between benefactors and beneficiaries about the balance between elite self-aggrandisement and collective needs and interests. In both contexts, the negotiation was mediated through complex rhetoric, with each side seeking to define notions of virtue, justice and freedom. Moreover, in both settings, the dêmos succeeded in developing a public language of citizenship and the common good which tied the wealthy into using their wealth for communal ends.82

Building on Ma’s picture, I would like to argue that Hellenistic honorary decrees also enacted, and preserved, two other types of speech act, crucial to the overall balance of the Hellenistic public sphere as a centre of political interaction. These correspond to the two varieties of civic rhetoric which are emphasised in turn in the subsequent two parts of Ober’s trilogy on the classical Athenian democratic public sphere: Political Dissent in Democratic Athens and Democracy and Knowledge.83

It is perhaps more straightforward to see what Hellenistic honorary decrees have to do with the final part of the trilogy, Democracy and Knowledge.84 That book discusses the success of Athenian civic institutions in spreading and coordinating useful knowledge across the citizenry, including knowledge about reciprocal incentives for cooperation. Like many classical Athenian institutions, Hellenistic debates about honours, and the resulting publication of honorary decrees for wide consumption, performed the crucial speech acts of creating, distributing and publicising useful knowledge about the community and its needs, and especially about incentives and rewards for civic contributions. Honorary decrees made clear to all what incentives were on offer to benefactors, but also provided public guarantees that the offer of such incentives was trustworthy. This was one of the principal functions of a stock feature of almost all honorary decrees: the so-called ‘hortatory clause’, which expressed the hope that the reliable grant of generous rewards to this benefactor would inspire – or incentivise – others to use their money and resources for civic ends.85 This dimension of the Hellenistic honorific process, increasingly emphasised by economic historians,86 was a matter of realist, unsentimental, efficient matching of potential with resources and rewards.

It might appear less obvious what Hellenistic honorary decrees have to do with the type of speech act studied in the remaining part of Ober’s trilogy, Political Dissent: the speech act of standing back from prevalent, consensual norms, and either criticising them or placing them within a broader ethical and humane context. This is where the Rosanvallon-style approach discussed in section 1 above, sensitive to the nuances of even apparently routine political language, can cast honorary decrees in a new light. Viewed through that lens, the honorific process did also create a space for critical reflection about basic ethical issues, which were increasingly explored in the longer decrees of the period after c. 150 BCE. For example, the Zosimos decrees at points called into question civic inequalities of status, especially in the reference to the ‘chance fate’ of slaves, mentioned above. Furthermore, those and other honorary decrees at times reflected about questions of wealth, benefit and well-being, in ways which subtly called into question some of the presuppositions central to the honorary decree as a political form, and integral to its first two types of speech act.

Honorary decrees were partly predicated on the celebration and singling out of individual success and contribution, at least partly conceived in material and financial terms. Also central to the form was a transactional relationship: the community rewarded contributions with valuable material and social capital, especially the ‘honour’ which was the aim of the central civic virtue of philotimia (love of honour). In dialogue with these more prudential and materialistic aspects of civic discourse, some honorary decrees explicitly probed notions of individual profit, benefit and success, in order to expose a deeper level of interdependence and ethical value.

This often took the form of metaphorical appeals to wealth and advantage, which exposed the hollowness of purely individualistic and transactional conceptions of them. At Mylasa in Western Asia Minor in the first century BCE, the benefactor Iatrokles was honoured by the civic subdivision of the Otorkondeis for releasing struggling debtors from their debts, ‘thinking that justice is more beneficial than injustice’.87 The word for ‘more beneficial’ (lysitelestera) closely evokes the financial realm of profit: Iatrokles was praised for recognising the deeper ‘profit’ of being a just citizen – which in this case required the repudiation of immediate profits from debt-collection. At late Hellenistic Priene, when the benefactor Athenopolis was praised for his assiduousness towards his interdependent fellow citizens (hoi synanastrephomenoi; compare above), he was explicitly said to have recognised that this was what ‘belonged to himself the most’ (νομίζων το[ῦτο α]ὑτῶι μέγιστον ὑπάρχειν):88 civic virtue was his most important ‘possession’, not any ephemeral money, property or honour. A similar approach could also be applied to non-citizens, including wealthy Romans: the citizens of the Aegean island polis of Tenos praised L. Aufidius Bassus for his financial help and clemency over debts, explaining that he thought that ‘for himself, the salvation of the polis and good repute among all were greater than all wealth’ (εἶναί θ’ ἑαυτ[ῶι] πλούτου παντὸς κρείττονα πόλεως σωτηρίαν καὶ τὴν π[αρὰ] πᾶσιν ἀγαθὴν εὐφημίαν).89

This picture of the competing speech acts of Hellenistic honorary decrees, corresponding to the three parts of Ober’s trilogy, offers a starting point for building further links between the Hellenistic poleis and modern theoretical models. The three discourses could be described as political, economic and ethical, but that convenient description underplays the political dimension of the second and third types of speech act. This problem can be solved through the modern distinction between ‘politics’ and ‘the political’, or ‘la’ and ‘le politique’, developed by Claude Lefort and others90 and recently applied to the classical Greek polis by Vincent Azoulay.91 ‘Politics’ is the structured clashing and coordination of interests within civic institutions, involving strenuous disagreement, competition and negotiation. The first and second dimensions of honorific discourse covered different parts of ‘politics’ in this sense. ‘The political’, by contrast, is the broader sphere of discourses, practices and rituals which create the shared meanings, trust and understanding which are a prerequisite for meaningful ‘politics’. The more reflective and critical aspects of honorary decrees helped to play this role within the Hellenistic polis.

The different aspects of honorific discourse were partly a conduit for ideas and values cultivated elsewhere: for example, their ethical-political language channelled the discourse of the gymnasium, philosophical schools and civic religion. Nonetheless, it was perhaps honorific debates which most successfully crystallised the productive tensions92 between different corners of the Hellenistic public sphere – assembly, commercial agora, gymnasium – into a single widely reproducible and accessible institution, which simultaneously engaged with the varied facets of ‘politics’ and ‘the political’ in all their richness and complexity.

4 CONCLUSION: THE PUBLIC SPHERE, PLURALISM AND PROSPERITY

A rich public sphere can be reconstructed for the Hellenistic poleis through the application of modern political and social theories which encourage close attention to the full range of political voices. Many features of that Hellenistic public sphere perpetuated and adapted features of the classical polis. The complex and geographically wide-ranging Hellenistic material can therefore enrich debates about the politics, society and economy of the classical polis, on which many other chapters in this volume focus.

For example, the rich, mixed discourse of Hellenistic honorific debates, studied in the previous section, shows that a range of contrasting motivations and values had to be in balance in a stable, prosperous Greek polis. To use two terms from Hellenistic decrees themselves, the philotimia (love of honour) of the ambitious citizenbenefactor, acutely sensitive to civic incentives, had to be in constant interaction with philagathia, ‘love of the good’, especially love of the common good and the ethical values of justice and solidarity which underpinned it.

This coheres with the complex analysis of classical polis society in the chapters in this volume by Lewis, Mackil and Azoulay and Ismard. Those chapters all point towards an interpretation of the ancient Greek economy which combines the best of Marxist, rational-choice and substantivist models. The Greek poleis owed their political and economic success not only to exploitation of non-citizens and slaves, but also to the creation of incentives to harness the entrepreneurial instincts of instrumentally rational citizens: for example, relatively secure property rights, efficient institutions and targeted honours and tax exemptions. Nonetheless, those incentives were effective only because they were balanced by countervailing institutions, norms and discourses which encouraged solidarity, self-criticism and mutual understanding, in ways which compensated for the inequalities and tensions resulting from strategic competition.93

The more community-oriented, reflective and critical discourses well-attested for the Greek civic public sphere, in civic epigraphy as well as high philosophy, were not luxuries made possible once economic rationality and institutions had created a stable, prosperous foundation. On the contrary, they themselves played a crucial role in sustaining trust and collective ambition. This was partly because they enabled poleis to cater to the full range of human needs, instincts and habits, as well as fostering them. The ancient Greek version of rational, incentives-driven individualism was itself a product of the complex Greek public sphere: it was only one in a complex matrix of options for a Greek citizen, which itself gained definition and force from its place within the matrix.

The traditional Greek polis – the city which made political debate and reflection both a civic responsibility and a public good – was thus present at its own mutation in the Hellenistic world. This meant that the social and political changes of the Hellenistic world, including cosmopolitanism and new types of elite power, were themselves strenuously debated at the time. Those debates gave rise to influential new open, cultural and cosmopolitan models of citizenship and the public sphere, explored in sections 2 and 3 above, which co-existed and competed with still vibrant more traditional ones. The Hellenistic cities can thus offer to modern political theory a valuable historical model of the problems and opportunities involved in reconciling philanthropy, cosmopolitanism and economic complexity with civic equality, solidarity and debate.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am pleased to thank the participants in the conference and my fellow editors of this volume for help with this chapter.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ager, S. L. (1996), Interstate Arbitration in the Greek World, 337–90 B.C., Berkeley.

Alberti, A. (1995), ‘The Epicurean theory of law and justice’, in A. Laks and M. Schofield (eds), Justice and Generosity: Studies in Hellenistic Social and Political Philosophy, Cambridge: 161–90.

Allen, D. S. (2006), ‘Talking about revolution: On political change in fourth-century Athens and historiographic method’, in S. Goldhill and R. Osborne (eds), Rethinking Revolutions Through Ancient Greece, Cambridge: 183–211.

Allen, D. S. (2010), Why Plato Wrote, Oxford.

Alston, R. (2011), ‘Post-politics and the ancient Greek city’, in O. van Nijf and R. Alston (eds), Political Culture in the Greek City after the Classical Age, Leuven: 307–36.

Appiah, K. A. (1997), ‘Cosmopolitan patriots’, Critical Inquiry 23 (3): 617–39. Appiah, K. A. (2006), Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers, New York.

Archibald, Z. H., J. K. Davies, V. Gabrielsen and G. J. Oliver (eds) (2001), Hellenistic Economies, London.

Archibald, Z. H., J. K. Davies and V. Gabrielsen (eds) (2011), The Economies of Hellenistic Societies, Third to First Centuries BC, Oxford.

Arendt, H. (1958), The Human Condition, Chicago. Arnaoutoglou, I. N. (2003), Thusias heneka kai sunousias: Private Religious Associations in Hellenistic Athens, Athens.

Azoulay, V. (ed.) (2014a), Politique en Grèce ancienne (= Annales HSS 69 (3)), Paris.

Azoulay, V. (2014b), ‘Repolitiser la cité grecque, trente ans après’, in Azoulay (ed.), Politique en Grèce ancienne (= Annales HSS 69 (3)), Paris: 689–719.

Balot, R. K. (2001), Greed and Injustice in Classical Athens, Princeton. Balot, R. K. (2006), Greek Political Thought, Oxford. Balot, R. K. (ed.) (2009), A Companion to Greek and Roman Political Thought, Oxford.

Beck, U. (2004), Der kosmopolitische Blick oder: Krieg ist Frieden, Frankfurt. Bertrand, J.-M. (1992), Cités et royaumes du monde grec: Espace et politique, Paris.

Bourke, R. (2016), ‘Revising the Cambridge School: Republicanism revisited’, Political Theory advance access 0090591716672231, first published 11 October 2016 as doi:10.1177/0090591716672231.

Bricault, L. and J.-M. Versluys (eds) (2014), Power, Politics and the Cult of Isis, Leiden.

Canevaro, M. and B. Gray (eds) (2018), The Hellenistic Reception of Classical Athenian Democracy and Political Thought, Oxford.

Cartledge, P. (2009), Ancient Greek Political Thought in Practice, Cambridge. Cohen, E. E. (2000), The Athenian Nation, Princeton.

Davies, J. K. (2013), ‘Words, acts and facts’, in M. Mari and J. Thornton (eds), Parole in movimento: Linguaggio politico e lessico storiografico in età ellenistica, Studi ellenistici XXVII, Pisa and Rome: 413–20.

Derrida, J. (1994), Politiques de l’amitié; suivi de L’oreille de Heidegger, Paris. Douzinas, C. (2007), Human Rights and Empire: The Political Philosophy of Cosmopolitanism, Abingdon.

Erskine, A. (1990), The Hellenistic Stoa: Political Thought and Action, London.

Esposito, R. (2010), Communitas: The Origin and Destiny of Community, Stanford. Forsdyke, S. (2012), Slaves Tell Tales: And Other Episodes in the Politics of Popular Culture in Ancient Greece, Princeton.

Fröhlich, P. (2004), Les cités grecques et le contrôle des magistrats (IVe–Ier siècle avant J.-C.), Geneva.

Fröhlich, P. and C. Müller (eds) (2005), Citoyenneté et participation à la basse époque hellénistique, Geneva.

Gabrielsen, V. (2007), ‘Trade and tribute: Byzantion and the Black Sea straits’, in V. Gabrielsen and J. Lund (eds), The Black Sea in Antiquity: Regional and Interregional Economic Exchanges, Aarhus: 287–324.

Gabrielsen, V. and J. Lund (eds) (2007), The Black Sea in Antiquity: Regional and Interregional Economic Exchanges, Aarhus.

Gauthier, P. (1985), Les cités grecques et leurs bienfaiteurs, Athens.

Goldhill, S. (1987), ‘The Great Dionysia and civic ideology’, Journal of Hellenic Studies 107: 58–76.

Goldhill, S. and R. Osborne (eds) (2006), Rethinking Revolutions Through Ancient Greece, Cambridge.

Gray, B. D. (2013), ‘The polis becomes humane? Philanthropia as a cardinal civic virtue in later Hellenistic honorific epigraphy and historiography’, in M. Mari and J. Thornton (eds), Parole in movimento: Linguaggio politico e lessico storiografico in età ellenistica, Studi ellenistici XXVII, Pisa and Rome: 137–62.

Gray, B. D. (2015), Stasis and Stability: Exile, the Polis, and Political Thought, c. 404–146 BC, Oxford.

Gray, B. D. (forthcoming), ‘Freedom, ethical choice and the Hellenistic polis’, History of European Ideas (special issue on the history of liberty, ed. V. Arena).

Grieb, V. (2008), Hellenistische Demokratie: Politische Organisation und Struktur in freien griechischen Poleis nach Alexander dem Grossen, Stuttgart.

Günther, L.-M. (ed.) (2012), Migration und Bürgerrecht in der hellenistischen Welt, Wiesbaden.

Haake, M. (2007), Der Philosoph in der Stadt: Untersuchungen zur öffentlichen Rede über Philosophen und Philosophie in den hellenistischen Poleis, Munich.

Hamon, P. (2009), ‘Démocraties grecques après Alexandre. A propos de trois ouvrages récents’, Topoi 16 (2): 347–82.

Hamon, P. (2012), ‘Gleichheit, Ungleichheit und Euergetismus: Die isotes in den kleinasiatischen Poleis der hellenistischen Zeit’, in C. Mann and P. Scholz (eds), ‘Demokratie’ im Hellenismus: Von der Herrschaft des Volkes zur Herrschaft der Honoratioren?, Die hellenistische Polis als Lebensform 2, Berlin: 56–73.

Harland, P. A. (2014), Greco-Roman Associations: Texts, Translations and Commentary. II. North Coast of the Black Sea, Asia Minor, Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft, Bd. 204, Berlin.

Heller, A. and A.-V. Pont (2012), Patrie d’origine et patries électives: Les citoyennetés multiples dans le monde grec d’époque romaine, Bordeaux.

Illingworth, P., T. Pogge and L. Wenar (eds) (2010), Giving Well: The Ethics Of Philanthropy, Oxford.

Ismard, P. (2010), La cité des réseaux: Athènes et ses associations VIe–Ier siècle av. J.-C., Paris.

Jones, A. H. M. (1940), The Greek City from Alexander to Justinian, Oxford. Kah, D. (2012), ‘Paroikoi und Neubürger in Priene’, in L.-M. Günther (ed.), Migration und Bürgerrecht in der hellenistischen Welt, Wiesbaden: 51–71.

Kah, D. and P. Scholz (eds) (2004), Das hellenistische Gymnasion, Berlin.

Kasimis, D. (2015), ‘Greek literature in contemporary political theory and thought’, Oxford Handbooks Online, doi 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935390. 013.40.

Kloppenborg, J. S. and R. S. Ascough (2011), Greco-Roman Associations: Texts, Translations, and Commentary. I. Attica, Central Greece, Macedonia, Thrace, Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft, Bd. 181, Berlin.

Laks, A. and M. Schofield (eds) (1995), Justice and Generosity: Studies in Hellenistic Social and Political Philosophy, Cambridge.

Lape, S. (2004), Reproducing Athens: Menander’s Comedy, Democratic Culture, and the Hellenistic City, Princeton.

Lefort, C. (1988), Democracy and Political Theory, Cambridge.

Leonard, M. (2005), Athens in Paris: Ancient Greece and the Political in Post-War French Thought, Oxford.

Liddel, P. (2007), Civic Obligation and Individual Liberty in Ancient Athens, Oxford.

Long, A. A. (2006), From Epicurus to Epictetus: Studies in Hellenistic and Roman Philosophy, Oxford.

Long, A. A. and D. N. Sedley (1987), The Hellenistic Philosophers, Cambridge. Loraux, N. (1981), L’invention d’Athènes: Histoire de l’oraison funèbre dans la ‘cité classique’, Paris.

Loraux, N. (1993), The Children of Athena: Athenian Ideas about Citizenship and the Division between the Sexes, Princeton.

McCarthy, G. E. (2002), Classical Horizons: The Origins of Sociology in Ancient Greece, New York.

Ma, J. (2002), Antiochos III and the Cities of Western Asia Minor, Oxford.

Ma, J. (2003), ‘Peer polity interaction in the Hellenistic age’, Past & Present 180: 9–39.

Ma, J. (2008), ‘Paradigms and paradoxes in the Hellenistic world’, Studi Ellenistici 20: 371–85.

Ma, J. (2013), Statues and Cities: Honorific Portraits and Civic Identity in the Hellenistic World, Oxford.

Ma, J. (2018), ‘Whatever happened to Athens? Thoughts on the great convergence and beyond’, in M. Canevaro and B. Gray (eds), The Hellenistic Reception of Classical Athenian Democracy and Political Thought, Oxford: 277–98.

Mack, W. (2014), ‘Communal interests and polis identity under negotiation: Documents depicting sympolities between cities great and small’, Topoi 18: 87–116.

Mackil, E. (2013), Creating a Common Polity: Religion, Economy, and Politics in the Making of the Greek Koinon, Berkeley.

Mann, C. and P. Scholz (eds) (2012), Demokratie’ im Hellenismus: Von der Herrschaft des Volkes zur Herrschaft der Honoratioren?, Die hellenistische Polis als Lebensform 2, Berlin.

Marchart, O. (2007), Post-Foundational Political Thought: Political Difference in Nancy, Lefort, Badiou and Laclau, Edinburgh.

Mari, M. and J. Thornton (eds) (2013), Parole in movimento: Linguaggio politico e lessico storiografico in età ellenistica, Studi ellenistici XXVII, Pisa and Rome.

Martzavou, P. (2014), ‘“Isis” et “Athènes”: Epigraphie, espace et pouvoir à la basse époque hellénistique’, in L. Bricault and J.-M. Versluys (eds), Power, Politics and the Cult of Isis, Leiden: 163–91.

Martzavou, P. and N. Papazarkadas (eds) (2013a), Epigraphical Approaches to the Post-Classical Polis, Fourth Century BC to Second Century AD, Oxford.

Morley, N. (2009), Antiquity and Modernity, Malden.

Mouffe, C. (2005), On the Political, Abingdon.

Moyn, S. (2012), The Last Utopia: Human Rights in History, Cambridge, MA.

Nancy, J.-L. (1999), La communauté désoeuvrée, 3rd edn, Paris.

Ní Mhurchú, A. (2014), Ambiguous Citizenship in an Age of Global Migration, Edinburgh.

Nippel, W. (2008), Antike oder moderne Freiheit? Die Begründung der Demokratie in Athen und in der Neuzeit, Frankfurt.

Ober, J. (1989), Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens: Rhetoric, Ideology, and the Power of the People, Princeton.

Ober, J. (1999), Political Dissent in Democratic Athens: Intellectual Critics of Popular Rule, Princeton.

Ober, J. (2008), Democracy and Knowledge: Innovation and Learning in Classical Athens, Princeton.

Ober, J. (2009), ‘Public action and rational choice in classical Greek political theory’, in R. K. Balot (ed.), A Companion to Greek and Roman Political Thought, Oxford: 70–84.

Ober, J. (2013), ‘Political animals revisited: The contemporary relevance of Aristotelian political theory’, The Good Society 22 (1): 201–14.

Oliver, G. J. (2007), War, Food, and Politics in Early Hellenistic Athens, Oxford.

Rancière, J. (1981), La nuit des prolétaires: Archives du rêve ouvrier, Paris.

Rawls, J. (2001), Justice as Fairness: A Restatement, Harvard.

Reich, R. (2010), ‘Toward a political theory of philanthropy’, in P. Illingworth, T. Pogge and L. Wenar (eds), Giving Well: The Ethics Of Philanthropy, Oxford: 177–95.

Richter, D. S. (2011), Cosmopolis: Imagining Community in Late Classical Athens and the Early Roman Empire, Oxford.

Robert, L. (1969–90), Opera Minora Selecta, 7 vols, Amsterdam.

Rosanvallon, P. (1992), Le sacre du citoyen: Histoire du suffrage universel en France, Paris.

Rosanvallon, P. (2006), Democracy: Past and Future, New York.

Rowe, C. and M. Schofield (eds) (2000), The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Political Thought, Cambridge.

Ryan, A. (2012), On Politics: A History of Political Thought from Herodotus to the Present, London.

Schofield, M. (1999), The Stoic Idea of the City, new edn with added foreword and epilogue, Chicago.

Schofield, M. (2000), ‘Epicurean and Stoic political thought’, in C. Rowe and M. Schofield (eds), The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Political Thought, Cambridge: 435–56.

Skinner, Q. R. D. (1996), Reason and Rhetoric in the Philosophy of Hobbes, Cambridge.

Skinner, Q. R. D. (2002), Visions of Politics. Vol. I: Concerning Method, Cambridge.

Teegarden, D. (2014), Death to Tyrants! Ancient Greek Democracy and the Struggle against Tyranny, Princeton.

Thompson, E. P. (1963), The Making of the English Working Class, Harmondsworth.

Thompson, E. P. (1971), ‘The moral economy of the English crowd in the eighteenth century’, Past & Present 50: 76–136.

van Bremen, R. (1996), The Limits of Participation: Women and Civic Life in the Greek East in the Hellenistic and Roman Periods, Amsterdam.

van Nijf, O. and R. Alston (eds) (2011), Political Culture in the Greek City after the Classical Age, Leuven.

Veyne, P. (1976), Le pain et le cirque: Sociologie historique d’un pluralisme politique, Paris.

Villa, D. (2001), Socratic Citizenship, Princeton.

Villa, D. (2008), Public Freedom, Princeton. Vlassopoulos, K. (2007a), Unthinking the Greek Polis, Cambridge. Vlassopoulos, K. (2007b), ‘Free spaces: Identity, experience and democracy in classical Athens’, Classical Quarterly 57: 33–52.

Wilson, J. (2014), ‘The jouissance of philanthrocapitalism: Enjoyment as a post-political factor’, in J. Wilson and E. Swyngedouw (eds), The Post-Political and its Discontents: Spectres of Depoliticisation, Spectres of Radical Politics, Edinburgh: 109–25.

Wilson, J. and E. Swyngedouw (eds) (2014), The Post-Political and its Discontents: Spectres of Depoliticisation, Spectres of Radical Politics, Edinburgh.

Wörrle, M. (1995), ‘Vom tugendsamen Jüngling zum “gestreßten” Euergeten: Überlegungen zum Bürgerbild hellenistischer Ehrendekrete’, in M. Wörrle and P. Zanker (eds), Stadtbild und Bürgerbild im Hellenismus, Munich.: 241–50.

Wörrle, M. and P. Zanker (eds) (1995), Stadtbild und Bürgerbild im Hellenismus, Munich.

1 On the early stages of this relationship, see McCarthy 2002 and Morley 2009; for its flourishing in twentieth-century France, Leonard 2005. The chapters in this volume reflect the current health of the relationship.

2 See, for example, McCarthy 2002: 17–23, on the importance of Hellenistic philosophy, especially Epicureanism, in the development of Marx’s thought.

3 See, for example, among many other works, Robert 1969–90; Gauthier 1985; Fröhlich 2004; Grieb 2008; Hamon 2009.

4 See, for example, Bertrand 1992; Ma 2002; 2008; Alston 2011.

5 Lape 2004 is an example of this style of approach to the Hellenistic public sphere, focused on the evidence of Menander; this chapter argues for the value of expanding the picture further to include Hellenistic inscriptions.

6 See, for example, Erskine 1990; Laks and Schofield 1995; Cartledge 2009: chs 9–10.

7 See, for example, Loraux 1981; Ober 1999; Cartledge 2009; Allen 2010; Balot 2001; 2006; also the approach of the different chapters in Balot 2009.

8 Liddel 2007.

9 Skinner 2002 collects Skinner’s writings on method.

10 See, for example, Ober 1999: ch. 1.

11 For this tendency in recent important works in this tradition, see Bourke 2016: 10–11.

12 See Skinner 1996.

13 Thompson 1963; for a similar approach to the French working class as an active contributor to political thought, see Rancière 1981.

14 Rosanvallon 2006: 74–5.

15 Rosanvallon 2006: 46. Rosanvallon 1992 is an extended example of this approach, applied to modern French debates about suffrage.

16 They can be usefully set alongside (for example) Greek popular stories and myths, recently well analysed in Forsdyke 2012 as evidence for Greek political ideology across the social spectrum.

17 Long 2006: 18 argues that Menander’s plays reveal the ‘uncertainty and confusion of popular ethics in the Hellenistic world’. The variety and contradictions of Hellenistic popular ethics can also be viewed in a different light, as argued here: as a sign of strenuous reflection and vibrant debate.

18 Compare Davies 2013, and the other papers in Mari and Thornton 2013.

19 This concept was developed by E. P. Thompson as a way of describing the cooperative, non-market ethics of the English peasantry when faced with economic issues (see Thompson 1971). But it can also be applied in a much broader sense: as a metaphor to convey the dynamic processes of production, exchange and distribution involved in any complex moral and ideological system, such as that of the Hellenistic world.

20 See Archibald et al. 2001; 2011.

21 Maiuri, Nuova Silloge 19; compare Ma 2013: 204–5.

22 Consider Seneca, De Otio 4.1; Long and Sedley 1987: text 67K. On the broader context: Schofield 1999; Richter 2011.

23 See Alberti 1995; Schofield 2000.

24 Ober 1999.

25 Ma 2018. See Grieb 2008, in particular, for a picture of overlapping democratic institutions in different cities in the early Hellenistic period.

26 Long 2006: 12–13, cf. 21.

27 Long 2006: 10.

28 See, for example, Nippel 2008: esp. chs 5–7.

29 See especially Arendt 1958.

30 Consider Rawls 2001: 21–3; Ryan 2012: esp. chs. 2–3.

31 See, for example, Derrida 1994; Nancy 1999; Esposito 2010. Marchart 2007 surveys this trend in Continental political philosophy.

32 See Appiah 1997 for a survey of modern debates about the complex relationship between cosmopolitanism and civic patriotism.

33 Relevant trends in political theory are summarised and discussed in Kasimis 2015: sections 3 and 4. For a similar historical approach: Vlassopoulos 2007a.

34 See Cohen 2000; Vlassopoulos 2007b.

35 See, for example, Loraux 1981; 1993.

36 See Goldhill 1987.

37 See Cartledge 2009: ch. 7.

38 See, for example, Ober 2013; compare Villa 2008: esp. 329, 352–3.

39 Ní Mhurchú 2014.

40 Alston 2011 develops similar proposals.

41 Mack 2014 surveys this phenomenon, with much further bibliography.

42 See Mackil 2013, with much further bibliography.

43 Polybius 2.37–8.

44 See Ager 1996; Ma 2018; compare Ma 2003.

45 See the papers in Heller and Pont 2012.

46 On Hellenistic associations at Athens, Arnaoutoglou 2003; compare Ismard 2010 (stressing too the importance of such associations as early as the archaic and classical periods). For the evidence for such associations across the Greek world, which becomes extremely rich in the Hellenistic period and Roman Empire, see the documents collected in Kloppenborg and Ascough 2011; Harland 2014.

47 See Martzavou 2014.

48 See, for example, SEG 15.849.

49 Compare Hamon 2012.

50 Kah 2012: 60–2. Kah offers a wide-ranging discussion of these decrees and their context.

51 I.Priene2 68, new edition of I.Priene 112, ll. 15–17.

52 See Kah 2012: 62–3, 68, citing other bibliography on this question.

53 I.Priene2 68, ll. 13–14. The word ‘foreigners’ is restored in a gap in the inscription (χάριτας π[αρὰ ξένοις κ]α̣ὶ ἀστοῖς), so it is not absolutely certain; but it is the most plausible complement to ἀστοί (‘citizens’) (compare Maiuri, Nuova Silloge 19, col. II, ll. 6–8, first discussed in the opening section above).

54 I.Priene2 63, new edition of I.Priene 107, ll. 17–21.

55 I.Priene2 64, new edition of I.Priene 108, ll. 16–18.

56 See Harland 2014: 195 for some examples.

57 See especially Aristotle, Politics 1280a34–b35. For the importance of ‘the fine’ (to kalon) as the aim of virtue and virtuous decision-making more generally in Aristotle, see, for example, Eudemian Ethics 1230a26–9; Nicomachean Ethics 1116b30–2, 1119b15–18, 1121b8–10, 1168b25–34.

58 Compare Martzavou 2014 for more on this trend in late Hellenistic communal life.

59 See again, for example, Vlassopoulos 2007a; 2007b.

60 Compare Beck 2004.

61 See, for example, Appiah 1997: 624–5; compare Appiah 2006.

62 See, for example, Douzinas 2007; Moyn 2012.

63 I.Priene2 69, new edition of I.Priene 113, ll. 53–6; compare Hamon 2012: 70–1.

64 Compare Gray 2013.

65 I.Priene2 68, ll. 73–6.

66 Robert 1969–90: vol. II, 814, n. 3. On the Hellenistic gymnasium: Kah and Scholz 2004.

67 I.Kyme 13, second century BCE.

68 For further discussion of the complex situation: van Bremen 1996.

69 Compare Wörrle 1995.

70 For full discussion, see Gray (forthcoming). For discussion of the earlier related uses of prohairesis in fourth-century Athenian civic discourse, see Allen 2006.

71 See Haake 2007: 106–10.

72 IG II2 1006 (122/1 BCE), ll. 16–20.