A manager looks at her computer screen when an employee is talking to her, obviously sending a message of disinterest or lack of time.

A manager looks at her computer screen when an employee is talking to her, obviously sending a message of disinterest or lack of time.You’re in the middle of one of the most important presentations of your life. You have done extensive research to be sure you project confidence and authority. Your computer-generated slides are flawless. You’re impeccably dressed. The information is simply rolling off your tongue. Things are going very well.

Then as your eyes scan the room, they come to rest on the most important person in the audience—the decision-maker. His eyes are on the conference table. His fingers play aimlessly with a pen. He is swiveling back and forth in the chair. He stops playing with the pen long enough to pick some invisible lint off his sleeve.

You feel your mouth go dry and a cold sweat break out on your forehead. You try to get back into the swing of your presentation, but you can’t take your eyes off Mr. Turned Off and Tuned Out. He might as well get up out of his chair and walk out of the room. His body language is saying it all.

When you engage in conversation or deliver a presentation, picking up on your audience’s many and ongoing nonverbal signals will improve your chances of communicating successfully with them. Likewise, monitoring and tailoring your own body language will help you send a positive message and encourage your audience to be straightforward and responsive.

Nonverbal communication includes so many areas that it may be easier to define what it isn’t rather than what it is. According to Dr. Paul R. Timm, in Managerial Communication: A Finger on the Pulse, most researchers agree that nonverbal communication includes everything except our use of words and numbers in written and oral communication. “The sobering reality,” says Timm, “is that what we say is almost always overridden by what we do. Indeed, regardless of what words convey, our bodies tell others how we feel about what we say.”

What we call nonverbal communication, or body language, includes stance, gestures, motion, facial expression (including eye contact), and use of personal space, to name a few. Most experts agree that nonverbal communication also extends to makeup, clothing, jewelry, and personal possessions. Here are some examples of poor nonverbal communication:

A manager looks at her computer screen when an employee is talking to her, obviously sending a message of disinterest or lack of time.

A manager looks at her computer screen when an employee is talking to her, obviously sending a message of disinterest or lack of time.

An aggressive sales rep takes his seat at a conference table and spreads his papers on either side of him, intruding on the personal space of those seated beside him.

An aggressive sales rep takes his seat at a conference table and spreads his papers on either side of him, intruding on the personal space of those seated beside him.

A new employee wears flashy, expensive jewelry, perhaps hoping to impress her new colleagues.

A new employee wears flashy, expensive jewelry, perhaps hoping to impress her new colleagues.

We send strong messages, either positive or negative, through the things we do, which are often more powerful than words.

The Voice as Nonverbal Communication

The voice also makes up a critical component of a spoken message. It’s not just what you say, but how you say it. The elements of pitch, pace, and power (volume, authority, passion) can project such qualities as timidity, hostility, confidence, suspicion, and collaboration. A monotone delivery may say to the audience that the speaker isn’t really engaged in his or her topic.

“Fillers” such as “Uh,” “okay,” and “you know” and hedging phrases such as “I think,” “I feel,” and “sort of” all undermine a speaker’s authority and confidence.

Some speakers fall into the habit of “uptalk”—or ending a declarative statement with an upward inflection as though it were a question. People who use uptalk come across as powerless, and their speech sounds unsure. They appear to need constant validation and agreement from their audience.

In the hierarchy of communication, spoken messages possess the most richness and flexibility because we can call on so many factors to deliver our ideas. When we are in someone’s presence, we have both the verbal component and nonverbal assets that we can leverage for success. What may be surprising is that research shows that words are actually the smallest part of a message—dramatically overshadowed by the nonverbal components.

More specifically, words comprise a mere 7 to 10 percent of a spoken message. Nonverbal factors make up the remainder of the message, with the voice accounting for another 35 to 38 percent. The rest comes from body language.

What these findings mean is that when the verbal and nonverbal components of our messages are at odds with each other, it’s no contest. The nonverbal factor will win every time. Too often, we send nonverbal messages without being aware of what we’re telling those around us. So being oblivious to that part of our communication can truly sabotage the most carefully planned communication.

When Does Communication Begin?

We begin to send messages from the first moment we are in our listeners’ presence. The way we enter a room, the way we make eye contact, the way we shake hands or nod in greeting, the way we take a seat and where we choose to sit, all send signals about whether we are friend or foe, knowledgeable or incompetent, and confident or nervous.

Studies show that it takes less than a minute for us to react either positively or negatively to someone, and, if that first impression is negative, several encounters are necessary to change that perception.

Just as it’s important for you to be aware of your own nonverbal communication and what it conveys to others, you must also be able to interpret others’ nonverbal responses to your communication.

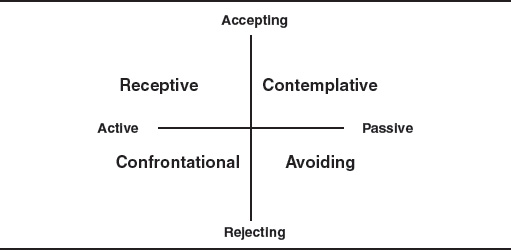

Be sensitive to the signals. In simple terms, we can categorize the “message” of body language by whether the audience seems to accept or reject our message and whether their response tends to be active or passive. The reaction can be represented as it is in the model shown in Figure 4-1.

Figure 4-1. Adapted from John Mole, Mind Your Manners: Managing Business Cultures in the New Global Europe.

Someone who leans toward you and nods energetically with a pleasant facial expression, perhaps even a smile, sends a signal that he or she agrees with what you’re saying and will probably approve your request or proposal. A tilted head and a body position that leans away from you, with more restrained body language, may be accepting but passive. This person is probably thinking about what you’re saying and willing to hear more.

Like acceptance, rejection has its own nonverbal communication—either active or passive. In passive rejection, the body language becomes evasive and tries to create some distance. The eyes wander; the head turns away; the hands fidget. You get the distinct impression that the person has mentally left the room. You may not get a straight reaction from the words, but the message is coming through all the same. In such a situation, you may want to switch, at least temporarily, to a subject that you know is more pleasing to the person or ask questions to create some dialogue. Active rejection is a little easier to interpret. It may take the form of an intense sullen stare. Body language may look as though the person is gearing up for an attack. When you experience active rejection, find a way to determine why before continuing in your current direction, perhaps by speaking to the person in private.

If you’re not sure, ask for clarification. As with any communication, the possibility for ambiguity in nonverbal communication often exists. For example, someone listening to you with his or her arms crossed, traditionally considered a negative signal, may simply be relaxed and comfortable with you. Avoid judging any one component in isolation. Look at the total package. If everything else looks positive, don’t worry so much about a single nonverbal signal.

However, if you are getting a consistently negative message or see a sudden change in someone’s demeanor, stance, or posture, it’s often helpful to ask questions to find out why the person feels that way. If you’re in a one-on-one situation, you might say, “Julie, you seem a bit uncomfortable with what I just said. Tell me what you’re thinking.” If you’re in a group setting, then address the group and invite people with concerns to voice those concerns or to share their perspective.

Based on our understanding of the impact of nonverbal communication, it’s not hard to accept that courtesy often begins with body language. And because the nonverbal component so outweighs the verbal component of a message, actions will always speak louder than words. This fact was brought home to me at a recent department meeting, when a colleague suddenly closed her notebook and pushed her chair back, crossing her arms. No one at the table had trouble recognizing her displeasure at what the meeting leader had just said.

People sometimes use body language to intimidate, exclude, denigrate, condescend, and humiliate. It’s safer than actually communicating those negative messages with words, because the meaning of the body language can be refuted and the message can simply be labeled a misinterpretation.

On the other hand, negative body language is often not deliberate and may just result from insensitivity. Once in a communication class that I was teaching, I led the students in a group decision-making exercise. Of eight students sitting around one rectangular table, all except one were male. In addition to being the only woman in the group, this student was also relatively new to the United States. She took a seat at the corner, which prevented her from being able to draw her chair under the table.

As the discussion progressed, the two people sitting on either side of her shifted their bodies so that their backs more and more were turned to her, in effect, creating a circle from which she was excluded. At the same time, she leaned back in her chair and withdrew from the discussion.

In debriefing the group on some of their decision-making techniques, I showed them a videotape of their meeting. What caught everyone’s attention was the group dynamics. The woman was offended by what she saw, and the other students were obviously embarrassed by their behavior. To a person, they all insisted that they had not acted deliberately. The results, however, were the same as if they had. It is equally true that the woman had not asserted herself during the conversation. In fact, as the meeting progressed, she had become increasingly disengaged, thereby contributing to the outcome.

Our nonverbal actions can also display concern, compassion, interest in, and respect for others. A smile and a nod as you pass someone in the hall, a hearty handshake to congratulate a colleague for a job well done, or obvious attentiveness to what someone is saying all foster positive interpersonal relationships.

Even in an adversarial situation, the right nonverbal messages can defuse hostility. For example, maintaining a composed demeanor and restraining your own body language when someone is angry with you can actually have a calming effect on the person. Keeping your voice low, limiting gestures, and maintaining a relaxed posture will discourage the other person from continuing to rant. On the other hand, displaying animation and enthusiasm with someone who is happy or excited can validate and support the person’s feelings.

Effective communication requires keeping your own body language in sync with that of the person with whom you’re communicating. For example, if your body language naturally tends to be expressive and dramatic, your style is perfectly suitable for communicating with an animated, enthusiastic person. However, you probably should tone it down when in conversation with a particularly low-key or restrained person. The idea is to make sure that your body language doesn’t make others uncomfortable because it either overpowers or underwhelms them. What if your own style tends to be restrained or low key? In that case, it’s best to be yourself and not try to match the style of someone who tends to be more spirited. If you do try, you will probably feel uncomfortable and your communication will project a degree of insincerity.

As you strive to communicate more clearly, understanding nonverbal communication can be a tremendous asset in your professional as well as personal communications. Being deliberate in your nonverbal communication and clearly interpreting and appropriately responding to the nonverbal cues of others will ensure that others see as well as hear what you’re saying.

To help you stay on track, here’s a brief summary of some common body language signals and their meaning.

Defensive/Confrontational

Arms crossed on chest

Crossing legs

Fist-like gestures

Pointing index finger

Reflective

Head tilted

Stroking chin

Peering over glasses

Taking glasses off and cleaning

Suspicious

Arms crossed

Sideways glance

Touching or rubbing nose

Squinting slightly

Open and Cooperative

Upper body in sprinter’s position

Open hands

Sitting on edge of chair

Tilted head

Hands behind back

Steepled hands

Insecure and Nervous

Chewing pen or pencil

Biting fingernails

Hands in pockets

Pinching or picking skin or clothing

Fidgeting in chair

Hand covering mouth while speaking

Poor eye contact

Perspiring

Tugging at ear

Playing with hair

Swaying

Frustrated

Short breaths

Tightly clenched hands

Pointing index finger

Rubbing hand through hair

Rubbing back of neck

Recognizing and understanding other people’s nonverbal signals is critical to communicating successfully with them.

Recognizing and understanding other people’s nonverbal signals is critical to communicating successfully with them.

What you say is almost always overridden by what you do. Body language tells others how you feel about what you say.

What you say is almost always overridden by what you do. Body language tells others how you feel about what you say.

Your voice makes up a critical component of a spoken message.

Your voice makes up a critical component of a spoken message.

Courtesy often begins with body language.

Courtesy often begins with body language.

Monitoring and tailoring your own body language will help you send a positive message and encourage your audience to be straightforward and responsive.

Monitoring and tailoring your own body language will help you send a positive message and encourage your audience to be straightforward and responsive.

Over the next thirty days,

I will stop ___________________________________________________

I will start ___________________________________________________

I will continue ________________________________________________