How much is one god beyond the other god?

Old Babylonian astronomical text

During the 1870s and early 1880s, numerous clay tablets from Babylonian archaeological sites found their way to antique dealers in Baghdad. The tablets had been found in the ruins of the ancient Assyrian city of Nineveh, where they had once formed part of the royal archive in the most famous library in the ancient Near East. The library was built by King Assurbanipal, who reigned during Assyria’s ascendancy in the eighth century BC. This historical treasure was preserved for future scholars when a combined force of Medes and Chaldeans sacked Nineveh in 612 BC destroying the library completely and burying the royal archive in the process.

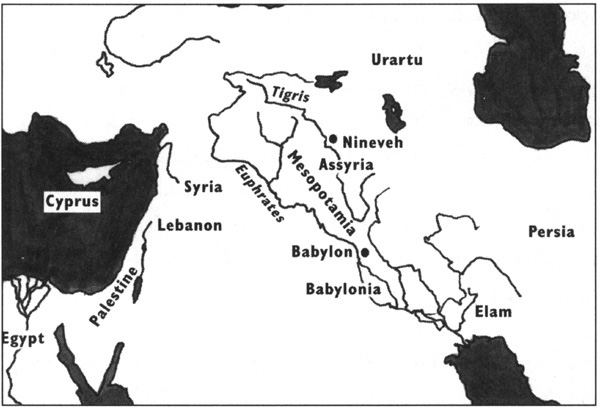

The Babylonian empire was situated between the two great rivers, the Tigris and the Euphrates, in an area historically known as Mesopotamia – the ‘land between two rivers’. Flowing south-eastward, the rivers converge to form a single valley, then proceed in parallel channels for the greater part of their course. Finally, they unite shortly before reaching the Persian Gulf. The joint delta of these rivers forms a plain about 275 km long. As in Egypt with the Nile, the delta offered many advantages to early people, continually attracting settlements for thousands of years. The fertile valley yielded abundant harvests, workable clay and the nutritious fruit of the date palm. Though large stone deposits were lacking, the early settlers used the local clay for building and even for writing material.

Figure 2.1. The Near East: Mesopotamia, the valley ‘between the two rivers’.

Wars were frequent in ancient Mesopotamia as tribes of hunters from the northern mountains and herdsmen from the south often tried to conquer this rich land. The Sumerians, the earliest inhabitants for whom there are written records, had entered the region by 3700 BC and gradually settled down to a life of farming. The Sumerians are credited with developing the earliest known form of writing.

In the 1880s, the British Museum purchased virtually all the clay tablets from Baghdad via London antique dealers. It was soon realised that among this vast collection were stories of the creation of the world and the great flood, as well as thousands of short texts on mathematics and astronomy. The latter texts contained records of astronomical observations made over hundreds of years in Assyria and Babylonia, and dating back to the third millennium BC. Today over a hundred and thirty thousand of these tablets are still stored at the Museum. It is an astonishing collection that comprises at least 98 per cent of all extant records of Babylonian astronomy.

One set of seventy tablets from Nineveh revealed a vast programme of astronomical observations which had been carried out in the second millennium BC. Known from its opening words as Enuma Anu Enlil (‘When Heaven and Earth …’), the set is a list, compiled over centuries, of celestial omens believed to have been sent to the king from the gods, warning him of impending disasters. Most of the tablets deal with interpretations of lunar and solar eclipses, conjunctions of planets, and comets, which the Babylonians took as dangerous omens.

In the early part of the second millennium BC, Hammurabi, the Semitic king from Arabia, conquered the Sumerians. With this victory he completed the unification of the region ‘between the two rivers’, and he made Babylon the capital city of his kingdom. Located on the left bank of the Euphrates, some 110 km south of modern Baghdad, for the next four hundred years Babylon was ruled by the Hammurabi dynasty during what is now called the ‘Old Babylonian period’, from 2000 to 1600 BC. It was not until after this golden age, however, when the fabled city became the leading centre and capital of the region, that the whole area became known as Babylonia.

The rich heritage of literature, religion and astronomy from the Old Babylonian period found in the ruins of the ancient cities of Babylonia would never have been preserved without a durable medium for recording. The practice of using clay tablets, inherited from the Sumerians, was perfect. These tablets were made from soft clay and written upon with a wedge-shaped stylus, which gave its name to the style of writing, cuneiform: the Latin word cuneus means ‘wedge’. For permanent records, a completed tablet was dried or baked until hard and usually protected by a clay case or envelope. Practically indestructible when dried, these tablets have provided modern scholars with a wealth of information about this period. Among some of the numerous treasures are thousands of astronomical and mathematical records. For example, the ancient site of Nippur, once the location of an astronomical observatory established by the Assyrian kingdom, has alone yielded some fifty thousand tablets.

Another legacy from Sumeria and the Old Babylonian period was the sexagesimal number system. Thousands of tablets dating from about 1800–1600 BC illustrate a number system that would seem unfamiliar to the modern reader. Instead of the decimal system based on the number 10, the Babylonians used the number 60 as the base (hence the name ‘sexagesimal’). Many historians have tried to explain the use of this unusual system of numbers. One theory is that the predominant role of astronomy in Babylonian society was instrumental in the adoption of the sexagesimal system. For example, the solar year is approximately 360 days, a figure which can easily be expressed as 6 x 60. Whatever the origin, the sexagesimal system of numeration has enjoyed a remarkably long life. Remnants survive even today in our units of time, 60 minutes in an hour, and angular measure, 360 degrees in a circle, in spite of the nearly universal acceptance of the decimal system for other counting schemes.

The Old Babylonian period was a time of great advancement for the development of what could be called the ‘sciences’. Yet it was one ‘science’ in particular that characterised the Babylonians’ world view – astrology. From early on in this period these people looked to the heavens and attempted to discover some kind of order in the skies. By the beginning of the first millennium BC, the Babylonians had developed skywatching skills and utilised them in the making of a calendar and a system of mathematics, based on the sexagesimal system, to track and simulate the motion of the Sun and Moon.

The regularity of celestial events provided early civilisations with the best means for bringing order and understanding to the cosmos. Their cataloguing of the heavens enabled them to identify celestial cycles of time and thus to develop calendars. Their knowledge of the recurrence of the seasons for agriculture and of reference points in the sky for navigation was essential for a developing culture.

Other ancient civilisations, such as the Egyptians and the Chinese, had impressive constellation maps, and developed schemes for tracking the motions of the Sun and the Moon in their attempts to solve the problem of how the Moon’s motion was synchronised with the Sun’s. Though the Moon provides a very convenient time cycle for dividing up the year, it has no bearing on the all-important seasons, which depend on the Sun.

The Babylonians went further than others in their efforts to use the Moon’s cycle as a universal timekeeping device. They did this by studying the motion of the Moon as it orbits the Earth. Their observations were accurately and systematically recorded over long periods of time. Next, they searched their records for repeating patterns of the Moon’s motion, such as the phases it passed through in the course of a month, and the succession of positions on the horizon where it rose and set. Finally, they simulated these patterns using mathematical models to predict future positions. All this bears a surprising similarity to modern applied mathematical science. It may be hard to believe, but this is how the Babylonians studied the motion of the Sun and the Moon over three thousand years ago.

However, developing a lunar–solar calendar was relatively simple compared with their deeper goal. Their aim in studying the motions of the Sun and Moon was actually to gain a complete understanding of the movements of these primary heavenly bodies. The astronomer-priests would then be able to anticipate, as much as possible, the appearance of a lunar or solar eclipse, the most fearful omens in the sky. An eclipse of the Sun or Moon was an awesome sight for the ancients. There is much evidence from early societies that they were profoundly disturbed by the darkening and disappearance of the two celestial bodies which seemed to govern and sustain their existence.

By the third millennium BC, the Babylonians had become obsessed with celestial omens, eclipses in particular. As a result these heavenly phenomena had assumed a central position in their religious beliefs. Unlike the Egyptians, who had little interest in the dozens of solar eclipses whose paths crossed the Nile during this same period, the Babylonians were so concerned about eclipses of the Sun and the Moon that they developed elaborate schemes to record these events over very long periods of time. This kind of record-keeping is very similar to our own. In fact, many have said that the Babylonians were the fathers of astronomy. However, while their methods of observing and record-keeping were similar to our modern applied mathematical astronomy, their motivations were very different. As J. J. Finkelstein has explained:

To the Mesopotamian, the entire objective universe was the crucial and urgent study, without any interposition of the self between the observer and the observed … There probably has never been another civilization so single-mindedly bent on the accumulation of information, and on eschewing any generalization or enunciation of principles.

The Babylonian quasi-religious belief in divination is an unexpected place to start a search through history for the origins of astronomy. Divination was an attempt to determine the will of the gods. To the Babylonians this was the same as an attempt to predict a future event. They believed themselves to be constantly surrounded by a host of evil spirits who caused insanity, sickness, accidents and death. To protect themselves against these spirits, they wore charms, put the image of a god at their doors and had magicians recite incantations. In addition, they depended on an elaborate hierarchy of priests who offered supplication to the gods. This was not idle superstition, but an important part of Babylonian philosophy: they believed that their very destiny was in the hands of the gods. They also believed, surprisingly, that their destiny was negotiable.

Divination rites were a way to communicate with the gods, to determine their will and perhaps change it. The discovery of signs from the gods, usually found in nature, was the first step in this process. As early as the third millennium BC they practised extispicy, the reading of the entrails of animals for clues from the gods to the nature of disasters to come. A sheep’s liver was commonly used for this practice. Extispicy was studied for centuries in the temple schools of Babylonia.

Considered as an act of religion, extispicy was an attempt to consult with the gods, to placate them, obtaining their cooperation and learning of their future intentions. The Babylonian gods were ‘sympathetic’, and might choose to change the divine decree, as a human king might. In addition to the entrails of sheep, the priests looked for clues to their fate in the behaviour of birds and other animals, the path of smoke from incense and the patterns of oil on water. We can look upon these divinations as the forerunners of readings of tea leaves settled in the bottom of a cup.

At some point in their history the Babylonians began to look to the heavens, thought to be the home of the gods. They sought their destiny in unusual celestial happenings – and there is none more unusual than an eclipse. Strange omens in the heavens, like strange patterns in the entrails of sheep, were not the cause of impending disaster but a warning intended to elicit the appropriate ritual of supplication. But this transition from extispicy to the birth of archaic astrology did not take place overnight. For example, a letter from a diviner from the time of Hammurabi in about 1780 BC reported on an eclipse of the Moon which he suspected was a bad omen. However, the letter shows that he was not yet confident in the new celestial form of divination. So in addition to celestial observation, the diviner also checks out the omen by means of extispicy.

Nevertheless, the practice of divination-astrology was growing. For example, a short manual of celestial omens that appeared during Hammurabi’s dynasty contained the following instruction, ‘If, on the day of its disappearance, the god Sin [the Moon] slows down in the sky [instead of disappearing suddenly], there will be drought and famine.’ Although celestial omens were beginning to be studied during the Old Babylonian period, the real development in the observation of the heavens came later, in the first millennium BC, in the time of the Assyrian empire.

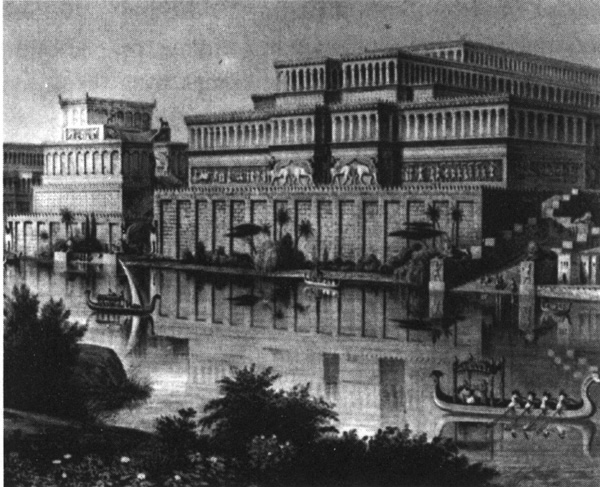

Figure 2.2. Nineveh, capital of Assyria, the walled city on the Tigris.

The Assyrians were an extremely warlike people who lived around Assur in the Tigris Valley. They had discovered the secret of smelting iron to make weapons, iron being a tougher metal than the bronze used by the Babylonians. With this advance they initiated a series of great and often cruel wars in the early part of the first millennium BC, destroying the first Babylonian state and extending their boundaries towards Asia Minor and Armenia. The new capital of the Assyrian empire was Nineveh. The political centre of a large military empire, the city was adorned with magnificent buildings, all made of the ubiquitous clay. As a great and rich commercial centre only a few hundred kilometres from Nineveh, Babylon initially retained its rank as a venerable seat of ancient culture. However, in 689 BC the Assyrians turned against the great city and had it destroyed. Even the mudbanks controlling the Euphrates were broken, flooding much of the city and turning the area into a swamp.

The Assyrians had adopted from the Babylonians the ancient and quasi-religious practice of ‘divination’, and absorbed the methods of observation and recording the movements of the Sun and Moon carried over from the Old Babylonian period. Their rulers also began to employ specialists in divination to continue the tradition of recording and interpreting eclipses, conjunctions of the Moon with planets, planetary movements, meteors and comets.

Having taken up the Babylonian philosophy of divination and developed their own astrology, the Assyrians applied their skills of organisation and discipline to the systematic observation of the heavens. They began to build astronomical observatories with temple towers all over the region. Thus began a programme of heavenly omen collection previously unknown in the ancient world. Reports that have come down to us from the period 709–649 BC indicate not just detailed observations, but, in the case of unfavourable eclipses, attempts at prediction. As the divination cult decreed, a successful prediction might provide the opportunity to make supplication to the gods against the expected danger.

While Assyria spread its kingdom by death and destruction as far as Asia Minor, parts of Persia and Egypt, the priests and scribes at Nineveh advanced the astronomical cult inspired by the sacred rites of divination. Over the hundred and fifty years of the empire’s predominance, a wealth of observations and predictions were recorded and collected in the great library at Nineveh. The library had been built by the Assyrian king Assurbanipal to store over twenty-two thousand clay tablets. Hundreds of reports were sent from the observation stations to the king’s palace. A cuneiform tablet of this period records that, ‘The King has given me the order: watch and tell whatever occurs, so I am reporting to the King whatever seems to me to be propitious and well portending and beneficial for the King, my Lord can know.’

Eventually, the harshness and cruelty of the Assyrians drove their subjects to revolt. They were attacked by the Medes from the north and the Chaldeans from the south. After a terrible siege the great capital of Nineveh was taken by storm (612 BC) and the great library was destroyed. The Assyrian empire, which had dominated the Fertile Crescent between the Tigris and the Euphrates for a century and a half, was gone. Nevertheless, it is one of the ironies of ancient history that only because the great library was completely destroyed were the clay tablets preserved. They were buried under the collapsed walls of the library.

After the defeat of the Assyrians, power passed into the hands of the Chaldeans. They revived the old capital of Babylon as the centre of their empire. To historians of science, the Chaldeans are known in particular for their obsession with celestial observation and prediction which they inherited from the Babylonians. There are conservative estimates that these people observed 373 solar eclipses and 832 lunar eclipses during their history, an impressive record given the rarity of these phenomena.

During the period of Assyrian domination, from the succession of the Chaldean King Nabonassar in the middle of the eighth century, precise historical records were systematically kept for the first time. Alternatively, as legend has it, Nabonassar destroyed all the records of the previous kings of Babylon so that the reckoning of the Chaldean dynasty would begin with him. This new beginning was so effective that, centuries later, Ptolemy, the Greek astronomer and geographer, could only begin his historical account of the Babylonian kings from this date, even suggesting that the era began at midday on 26 February 747 BC.

This day also marks an important beginning in the history of astronomy, because from here on the Chaldeans recorded highly accurate astronomical observations on a regular basis. Though it is true that the motive for these records was still mainly astrological, the observations became increasingly what can only be described as scientific.

The astronomical texts, records of observations and predictions, reveal that through centuries of pre-eminence under the Chaldean dynasties, and even during later periods of decline, celestial observations continued to be made at Babylon on a regular basis and with little change of pattern. Modern scholars estimate that the programme lasted almost eight hundred years, until after the time of Christ. The most recent surviving astronomical text dates from AD 75, an almanac prepared from contemporary observations. Thus, from 750 BC to AD 75, there exists an archive of what the observers of Babylon saw in the heavens and recorded on clay tablets.

To put this achievement into perspective, consider an equivalent project to make similar observations at Windsor Castle, starting at about the time of the castle’s construction in the early thirteenth century. This was the time of Richard the Lionheart and the Magna Carta. If the continuity of the Windsor ‘archives’ were to match Babylon’s, the skywatching would still be going on today, as the twentieth century gives way to the twenty-first. The observations would have continued through the reign of the Plantagenets and the War of the Roses, Elizabeth and the Spanish Armada, the Civil War and the Restoration. Perhaps in the late seventeenth century the observations would have been taken over by the Astronomer Royal, and examined by Isaac Newton and Edmond Halley. During Victoria’s reign the project would no doubt have been supervised by Prince Albert, science enthusiast and overseer of great civic works. Finally, in the twentieth century, astronomer-priests would get deferments from the Great War, survive the blitz of the Luftwaffe and even the celebrations marking the dawn of the new millennium.

Figure 2.3. A Babylonian cuneiform text: an astronomical diary from 164 BC (British Museum).

British Museum, London

The priests and scholars responsible for this remarkable coordinated programme have been called the Babylonian watch-keepers. Their main motive for skywatching at Babylon was no doubt astrological; they generalised the observations to produce almanacs that were used for astrological predictions. Nevertheless, as the centuries passed and mathematical models were applied to reproduce past observations and predict future movement of celestial bodies, the cult of astrology came more and more to resemble astronomy.

Another aspect of the Chaldeans’ astronomy was their ability to use their extensive catalogue of celestial observations. While the watch-keepers continued to search the heavens for omens, astronomers were able to develop a mathematical theory from their study of the records. Their analysis of the records of ancient observations suggested the possibility of creating models of the movement of the Sun and the Moon. From these models, astronomers would then be able to predict future astronomical phenomena. Once they had seen this possibility, the Chaldeans realised that they needed better accuracy in their observations. As early as 1000 BC their scribes had recognised eighteen constellations, groups of stars forming recognisable patterns in the sky. By 500 BC these constellations were systemised and identified, singly or sometimes in pairs, with the twelve lunar months as the Moon, Sun and the planets moved through the sky. For example, the second month of the Babylonian year, corresponding to mid-April to mid-May, had symbols of both Taurus and the Pleiades; the third month, Gemini and Orion; and the twelfth month, Pisces and Pegasus.

In order to introduce firm delineations for the purposes of astronomical diaries and observations, the ecliptic path along which the Sun moves was divided into twelve equal parts of 30°. This was called the zodiac, from the word for ‘animal’ – most zodiacal figures are animals or people. The first evidence of the use of this zodiac in a diary is from 464 BC, and by about 400 BC the zodiacal constellations had been clearly defined, beginning with Aries for the first month, corresponding to mid-March to mid-April. This system of zodiac constellations has lasted essentially unchanged to the present day, both for the science of astronomy and the pseudoscience of astrology.

We might expect that for chroniclers who recorded every solar and lunar eclipse over many centuries it would be natural to look for patterns. This would have given them a means of predicting the most ominous happenings in the heavens. But it wasn’t until the Hellenistic period, from the fourth century BC onwards, that the Chaldean astronomers began to use previous reports and diaries to look for repeating cycles.

Figure 2.4. The zodiac: a belt of constellations along the ecliptic, originated by the Babylonians.

From their study of previous eclipses the astronomers were able to collate a set of rules for the prediction of lunar eclipses. They noticed that lunar eclipses never occur within six months of one another. They also discovered that if two lunar eclipses occur six months apart, they will be followed by a third lunar eclipse six months later. This happened quite often. If a lunar eclipse does not occur in an expected series, it could have occurred during daytime when the Earth’s shadow on the full Moon would not be noticed. Thus the series is not broken, and another eclipse may occur six months later. If a lunar eclipse is observed a year or more after the last, and one month earlier than would have been expected on the basis of the last series, by then broken, it represents the first eclipse in a new series.

The short series described by these guidelines form part of a larger pattern of 18 years’ duration. Within that 18-year cycle there are five such short series, followed by a sixth series which closely resembles the first. This begins a new 18-year cycle. Using these guidelines, an 18-year cycle for lunar eclipses was discovered. This cycle is called a saros, a Babylonian word meaning ‘repetitive’ though the Babylonians themselves did not use the word in this context.

A cycle of lunar eclipses is naturally easier to discover than a cycle of solar eclipses. There is a very simple reason for this: a lunar eclipse, which happens when the Earth’s shadow falls on the Moon, can be seen from every point on the Earth’s surface from where the Moon is above the horizon. Solar eclipses are seen less frequently.

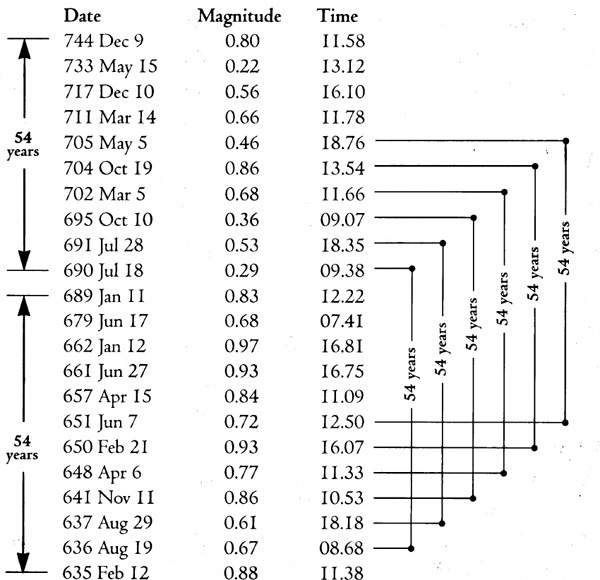

Yet given that a lunar and a solar eclipse often occur a fortnight apart, it seems probable that the Chaldean astronomers of the fourth century BC may have guessed that an 18-year cycle also existed for solar eclipses. There is another theory of how they might have discovered it. This is shown in Table 2A, which lists certain solar eclipses observed by Assyrian astrologers in the seventh and eighth centuries BC. The magnitude of an eclipse is the fraction of the Sun’s diameter that is covered by the Moon. It can be seen from the dates that all these solar eclipses have a previous eclipse predecessor 54 years earlier.

Table 2A. Solar eclipses recorded at Nineveh, 744–635 BC.

Once this pattern was noticed, it could be guessed that the number 54 might be a combination of a smaller series within the 54-year cycle, like 2 x 27 years or 3 x 18 = 54. (The reason why the Babylonians could observe a 54-year cycle directly at the same longitude but not an 18-year cycle is explained in the next chapter.)

However, the most important achievement of this entire effort from the standpoint of the history of science was the Babylonian solution to the problem of the motion of the Sun and the Moon. This solution undoubtedly grew out of problems associated with the development of the calendar. It was the Babylonians’ custom to define the beginning of each month as falling on the day after the new Moon when the lunar crescent first appears after sunset. Originally this day was determined by observation, but later they wanted to calculate it in advance. However, by about 400 BC they had sufficient numbers of observations of the motions of the Sun and the Moon through the zodiac to know that these bodies did not have a constant speed. They appeared to move with increasing speed for half of each revolution, to a definite maximum, and then to decrease in speed to a measurable minimum.

Today it is known that the gravitational pull of an attracting body on an orbiting body produces a characteristic elliptical orbit in which the moving body is always speeding up or slowing down. The Babylonians attempted to represent this cycle arithmetically by giving the Moon a fixed speed for its motion during one half of its cycle, and a different fixed speed for the other half. Later they refined the mathematical method by allowing the speed of the Moon to increase steadily from minimum to maximum during one half of the cycle, and then to decrease to the minimum in the other half of the cycle.

With their calculations of the lunar and solar months, Babylonian astronomers could predict the time of new Moon and the day on which the new month would end. They would know the daily positions of the Moon and the Sun for every day during the month. This was a true mathematical science, which reached the height of its creativity during the Seleucid period in the second century BC, when the astronomers moved away from the ancient city of Babylon. It was now possible to reduce the predictions of celestial basics to mathematical models and not to rely heavily on observation. Though this led to highly precise predictions, the Babylonians surprisingly never formulated any geometrical model of the cosmos which might have supported their calculations. Instead, the problems were solved arithmetically without recourse to a cosmology of the type developed by the Greeks; that would follow only when Babylonian and Greek astronomy were linked after the conquests of Alexander the Great.

Through further studies, the Babylonian scribes had learned to produce ephemerides – tables of the future positions of the Sun, the Moon and the planets. So, in addition to the systematic records of careful observations available to them, the scribes made use of their sexagesimal number system and their knowledge of mathematics to take full advantage of the cycles revealed by their observational records. Once the ephemerides were completed, the astrologers could make predictions even without the observations, and in all kinds of weather. The importance to the future of astronomy, meteorology, navigation, and the like of this new mode of providing written, predictive information hardly needs to be emphasised.

During this period of astronomical development, the Chaldean dynasty lost control of political power in Babylon. After less than a hundred years their empire was overthrown by a powerful alliance of Medes and Persians in 538 BC, and Babylon became part of the Persian empire under Cyrus the Great. The days of independent Mesopotamian kingdoms were over. But still the astronomical observations continued.

During more than two centuries of Persian rule, Babylonian astronomy continued to improve in the accuracy of observation and mathematical prediction. Then the city of Babylon again shifted its political allegiance. In 330 BC the Persians were conquered by the armies of Alexander the Great, beginning one of the most significant periods of cultural diffusion in history. It became known as the Hellenistic period. Alexander had planned to restore some of the glory of Babylon by making the city his eastern capital. Unfortunately, he died there only seven years later in the palace of Nabuchadnezzar II, in 323 BC. Within fifty years of Alexander’s death the Greek ruler Antiochus I ordered much of the population of Babylon to move to the newly founded metropolis of Seleucid, 100 km to the north. The old city never recovered from this transfer of its intellectual and political core, though Hellenistic rule continued there well into the second century BC. At Seleucid, Babylonian astrology was replaced by a highly advanced form of Greek astronomy. One aspect of the development included Aristarchus of Samos’ hypothesis that the apparent daily motion of the sky could be explained by assuming that the Earth turns on its axis once every twenty-four hours and, with the other planets, revolves around the Sun. This heliocentric explanation was rejected by most contemporary Greek philosophers, who could not believe that a big heavy Earth could revolve around the light bodies in the heavens. The geocentric system, bounded by the celestial sphere, would remain virtually unchallenged for two thousand years.

Thus ended the two-thousand-year Babylonian cultural development of watching the heavens. It had started with a concept of divination which inspired an obsession with observation and record-keeping of celestial omens. This led to mathematical simulation and the discovery of the saros series, which provided a method of predicting when an eclipse would take place. In Babylonian astronomy we have a model for scientific progress. Though it originated with the superstitious beliefs of astrology, it grew into a methodology that we can now see as foreshadowing the concepts and procedures used in the scientific world today.

The marriage between astrology and astronomy has had a strange history. There is no question that during the Babylonian era the motivation for this vast accumulation of celestial data was to satisfy the demands of rulers and general population alike for astrological divination. For many hundreds of years, particularly during the late first century BC, these data were obtained more and more by scribes and priests who could only just be described as astronomers.

The Babylonians were never attracted to the form of astrology popular today, which is based on the Greek geometric cosmology in which the celestial-sphere model and the zodiac provide a framework in which interpretations of personality traits for horoscopes and birth charts are drawn from ancient myths and legends. With Babylonian astrology, celestial configurations were not the final word: there was still hope that unfavourable events foretold could be avoided. Such a philosophy was therefore quite different from the version of astrology inherited by today’s practitioners from the Greeks.

The change from divination to the more recognisable Greek astrology was due mainly to the influence of two major writings from ancient Greece – Plato’s Timaeus and Ptolemy’s Tetrabiblos. Thereafter, classical astrology provided a naturalistic rationale for natal horoscopes, marking the split between astrology as divination (Babylonian) and astrology as science (Greek). Greek astrology eventually split off and grew into the science of astronomy. It is sad that this fact is not appreciated in a positive way by historians of science. No doubt this is a reaction against the popularity of the absurd claims of astrologers in interpreting birth charts and horoscopes which to the scientific mind are completely untenable.

There can be little doubt that, without the influence of astrology, astronomical observations would never have been made in the ancient world. Though today’s astronomers and other scientists loathe the concept, they should admit that this absurd pseudoscience has made at least one positive contribution to the history of science.

It is interesting to see how scientists today make use of the Babylonian records in astronomical and geological studies. One example of this heritage is the new determination of the change in the rotational speed of the Earth. Who would ever have dreamt that the report by an astronomer-scribe of a solar eclipse observed at Babylon in 136 BC would allow a modern physicist to accurately measure the decrease in the spin rate of the Earth twenty-two centuries later? But this is exactly what has happened.

It is well established that the Earth’s rotation is slowing down. This is happening because of the forces exerted by the Moon on the Earth through the ebb and flow of the tides. As the Earth’s rotation rate decreases, there is a corresponding increase in the length of the day of 2.3 milliseconds per century. The goal of many archaeologists working in astronomy today has been to use ancient records of precise celestial events to get a measure of the rotation rate that is independent of any theory. An eclipse observed at a particular point on the Earth thousands of years ago could be compared to a present-day computer projection of that same eclipse assuming a uniform spin rate throughout time. Any difference in the two eclipse paths would require a correction to bring them into agreement. This correction would, it was hoped, corroborate the experimentally determined rate of slowing of the Earth’s rotation.

F. R. Stephenson of Durham University has for several years been studying the eclipse records of the Babylonian astronomers as recorded on cuneiform clay tablets. In 1998 he was able to reliably fix an exact date in 136 BC when an eclipse was recorded at the ancient city of Babylon. He compared this record with a prediction of the path of the same eclipse made using modern computer techniques. For the calculation, he assumed that there was no slowing down of the Earth – that its spin rate twenty-two centuries ago was the same as it is today.

The result was an eclipse track which misses the ancient city of Babylon by a considerable distance. With no correction for the slowing down of the Earth, the eclipse track crosses the latitude of Babylon (32.5°N) at a longitude of 4.3°W, as shown in Figure 2.5. A correction needs to be made to bring the eclipse track back to Babylon, where it was observed, at longitude 44.5°E. This is a considerable correction, almost 50 degrees of longitude, and can be made with a great accuracy.

Figure 2.5. Long-term changes in the Earth’s rotation revealed by correcting the path of an eclipse observed at Babylon in 136 BC. The latitude of Babylon is 32.5°N.

Stephenson, F. R., Historical Eclipses and Earth’s Rotation (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1997)

The measured change gives an increase in the length of the day of 1.7 milliseconds per century. In other words, the Earth is not slowing down as fast as the theory of tides would predict, which is 2.3 milliseconds per century. There must be another component speeding up the spin rate of the Earth and decreasing the length of the day by 0.6 milliseconds per century. This component is thought to result from the decrease in the Earth’s obliqueness, its flattening of its spherical shape, following the last ice age, and is consistent with recent measurements made by artificial satellites.

The thousands of dusty clay tablets in the British Museum, a product of our ancestors’ attempts to placate the gods, may hold yet more secrets of ancient celestial configurations.