Oh, dark, dark, dark amid the blaze of noon, Irrecoverably dark, total eclipse Without all hope of day

Milton, Samson Agonistes

‘O, swear not by the Moon, th’inconstant Moon, That monthly changes in her circled orb …’

William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet

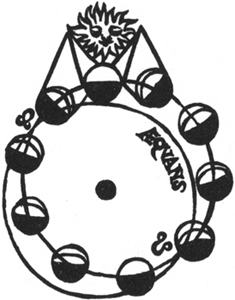

WEDNESDAY, 11 AUGUST 1999 will see the last total solar eclipse of the twentieth century. The path of totality, where the Moon’s umbral shadow tracks across the Earth’s surface, starts in the Atlantic Ocean and crosses central Europe and the Middle East, ending at sunset in the Bay of Bengal. A partial eclipse will be seen within the much broader path of the Moon’s penumbral shadow, which includes north-eastern North America, all of Europe, northern Africa and the western half of Asia. The totally eclipsed Sun will be visible across Europe, as most of the path passes across densely populated areas. It could be the most widely viewed eclipse in history.

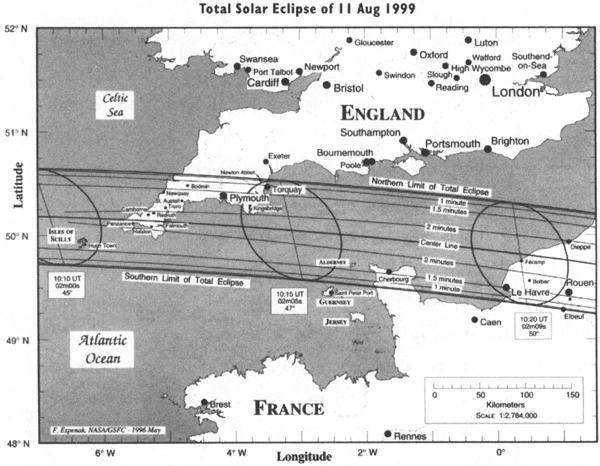

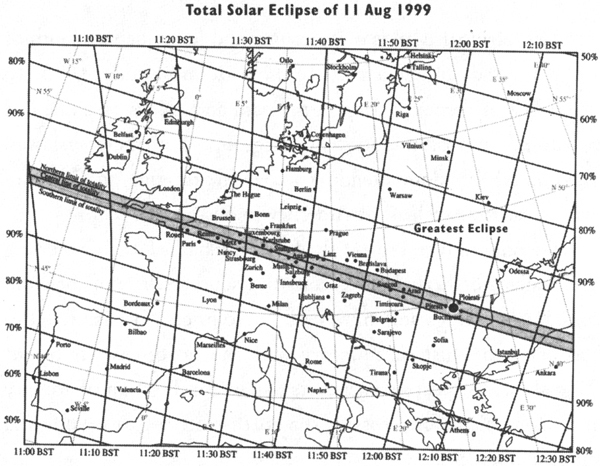

A global view of the eclipse path is shown in Figure 8.1. On this map, vertically drawn lines denoting the position of the umbra at different times are labelled in UT, Universal Time. This is a time-scale used by astronomers which is independent of time zones. To convert to British Summer Time (BST), add one hour to UT. Looking closely at the grid lines on the map, it can be seen that the Moon’s shadow sweeps over the British Isles between 10:00 and 10:30 UT, or 11:00 and 11:30 BST.

Like every other eclipse, the 11 August 1999 event is part of a saros series: it is the twenty-first eclipse of saros series 145. All eclipses in this series occur at the Moon’s ascending node, and subsequent eclipses in the series progress southward, in the opposite direction from the eclipses of saros series 136, described in Chapter 3, which take place at a descending node. This is a convenient rule of thumb: even-numbered saros series occur at a descending node, odd-numbered series occur at an ascending node.

Figure 8.1. Global view of the solar eclipse on 11 August 1999.

Espenak, F. and Anderson, J., Total Solar Eclipse of 1999 August 11, NASA Reference Publication 1398 (NASA, March 1997)

Saros series 145 is a young one, which began with a minuscule partial eclipse at high northern latitudes on 4 January 1639. After fourteen partial eclipses of increasing magnitude, the first annular eclipse occurred on 6 June 1891. The event was of 6-seconds duration, and the path swept through eastern Siberia and the Arctic Ocean. Although on this occasion the tip of the umbra fell just short of the Earth’s surface, the Moon’s distance from the Earth at each subsequent eclipse in the series gradually decreased, and the umbra struck the Earth at the very next eclipse, on 17 June 1909.

The third central eclipse of Saros 145 occurred on 29 June 1927. It was the first total eclipse of the series, and the path passed across England in addition to Scandinavia and Siberia. In the next eclipse in the series, on 9 July 1945 the path of totality began in Idaho and quickly swept north-east through Montana, Saskatchewan and Manitoba. After crossing Hudson Bay, Greenland and the North Atlantic, the umbra returned to Scandinavia and Siberia. The fifth central eclipse occurred on 20 July 1963. Its path crossed Alaska, central and eastern Canada, and Maine. The last eclipse of the series before 11 August 1999 took place on 31 July 1981. Its path crossed central Siberia, Sakhalin Island and the Pacific Ocean, where it ended north of Hawaii.

One saros cycle later, on 11 August 1999, the last solar eclipse of the millennium arrives. The path of totality starts at sunrise about 300 km to the south of Nova Scotia, where the Moon’s umbral shadow begins its journey at 10:30:57 BST. At this hour on mainland Britain, the Sun has already been above the horizon for a few hours. The first observers at sea to view the eclipse at sunrise will enjoy a mere 47 seconds of totality. At this point the width of the shadow is 49 km.

For the next 40 minutes, as the shadow sweeps across the North Atlantic, passing through several time zones, it does not touch any land. It reaches the Isles of Scilly off the south-western coast of England at 11:10 BST. Here the Sun is 45° above the eastern horizon. The eclipse duration is 2 minutes at the central line of the eclipse, and the path width has expanded to 103 km. The shadow now pursues its easterly track with a ground velocity of 54.6 km per minute.

Somewhere in this region of the shadow’s journey, the supersonic jetliner Concorde is scheduled to fly into the umbra. As a publicity stunt for the world’s fastest jet, Concorde will attempt to keep up with the umbra as it crosses the Atlantic, affording its occupants a prolonged view of the fully eclipsed Sun. But Concorde’s best effort will not be enough to keep up with the moving shadow. The plane’s cruising speed is approximately 45 km per minute. As a result, the shadow will outpace it by about 10 km per minute. Since the diameter of the shadow is 103 km, Concorde’s passengers will experience totality for about 10 minutes.

At 11:11 BST the Moon’s umbra will touch the British mainland for the first time since 1927 (it won’t be back until the year 2090). The shadow will track across the mainland for just 4 minutes. Its much-anticipated arrival along the shores of the Cornish Peninsula will give eager observers a brief taste of totality. Plymouth, the largest English city in the path, is north of the centre-line and witnesses a total phase lasting I minute 39 seconds. However, I minute and 35 seconds before the umbra reaches Plymouth it passes over Falmouth, which is directly on the centre-line of the eclipse.

A sky-watcher’s view at the seaside town of Falmouth on this special morning will never be forgotten. At 9:57:06 BST the Sun, 36° above the horizon, will just be touched by the Moon at first contact. Over the next period of I hour, 14 minutes and 9 seconds more and more of the Sun’s disk will be covered by the Moon, and the sky will gradually darken. Birds will stop chirping, flowers will close up and the impression of sunset will be created. Street lights activated by light levels will switch on.

The safest and most inexpensive method of observing the eclipse is by projection. A pinhole or small opening in a suitably large sheet of material will form an image of the Sun on a screen placed about a metre behind it. Alternatively, the many gaps in a loosely woven straw hat, or even the spaces between interlaced fingers, can be used to cast a pattern of solar images onto a screen. A similar effect is seen on the ground below a broadleaf tree: the many ‘pinholes’ formed by overlapping leaves create hundreds of crescent-shaped images of the eclipsed Sun.

Binoculars or a small telescope mounted on a tripod can also be used to project a magnified image of the Sun onto a white card positioned behind the eyepiece. All of these methods will provide a safe view of the partial phases of the eclipse. However, it is essential to ensure that no one looks at the Sun through any optical instrument. The main advantage of the projection methods is that nobody is looking directly at the Sun. The disadvantage of pinhole method is that the screen must be placed at least a metre behind the opening to get a solar image that is large enough to see easily.

Observing the Sun can be dangerous if you do not take the proper precautions. While environmental exposure to UV radiation is known to contribute to the accelerated ageing of the outer layers of the eye and the development of cataracts, the concern over improper viewing of the Sun during an eclipse is for the development of ‘eclipse blindness’ or retinal burns. The result is a loss of visual function which may be either temporary or permanent, depending on the severity of the damage.

The only time the Sun can be viewed safely with the naked eye is during the total phase of a total eclipse, when the Moon completely covers the disk of the Sun. It is never safe to look at a partial or annular eclipse, or the partial phases of a total solar eclipse, without the proper equipment and techniques. Even when 99 per cent of the Sun’s surface, the photosphere, is obscured during the partial phases of a solar eclipse, the remaining crescent Sun is still intense enough to cause a retinal burn, even though illumination levels are comparable to twilight. Failure to use proper observing methods may result in permanent eye damage or severe visual loss.

At any time other than during totality, the Sun must be viewed through a filter specially designed to protect the eyes. Most filters have a thin layer of chromium alloy or aluminium deposited on their surfaces that attenuate both visible and near-infrared radiation. A safe solar filter should allow less than 0.003 per cent of the Sun’s light to pass through it.

These warnings can never be repeated too often. To look directly at the Sun is to risk permanent blindness. Looking at the Sun through binoculars or a telescope increases the risk enormously.

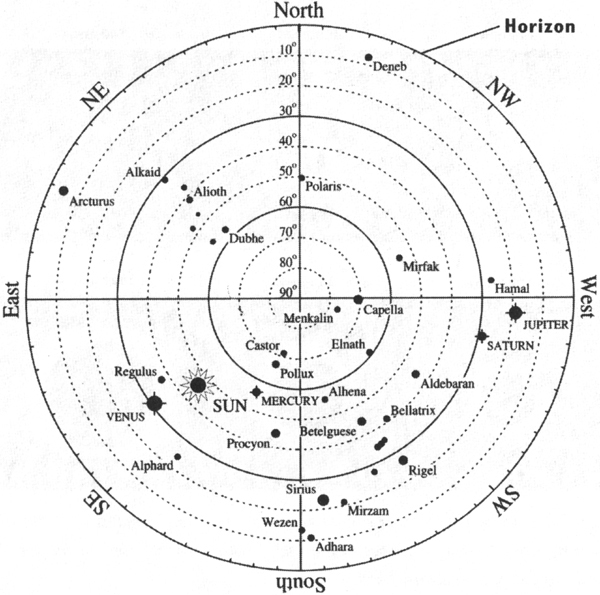

The eclipse may be safely photographed provided the above precautions are followed. Any kind of camera with manual controls can be used to capture this spectacular event. However, a lens with a long focal length is recommended so as to produce as large an image of the Sun as possible. A standard 50 mm lens yields a minuscule 0.5 mm image, while a 200 mm telephoto or zoom lens produces a 1.9 mm image. A focal length of 500 mm will give a solar image of 4.6 mm. All these are shown in actual size on 35 mm film in Figure 8.2, together with images obtained with lenses of very long focal length.

As the sky darkens for viewers in Falmouth, the planets Mercury and Venus will become visible, even before totality arrives. The last beams of sunlight pass between mountains at the Moon’s edge to form Baily’s beads and the diamond ring effect. And then, at 11:11:15 BST, second contact occurs and totality begins. As the 2 minutes and 6 seconds of totality start, the solar corona, the most distinguishing feature of a total eclipse, springs into view. After 63 seconds totality is half over. This is the moment of maximum eclipse, with the Sun in a south-easterly direction, 50° east of due south and 46° above the horizon. The Sun is still climbing in the sky as it has not yet passed the local meridian, which occurs nominally at noon.

Figure 8.2. Field of View of the eclipsed Sun on 35 mm film (actual size) for the same refracting telescope at various focal lengths. To photograph the Sun’s corona, the focal length should not exceed 1500 mm.

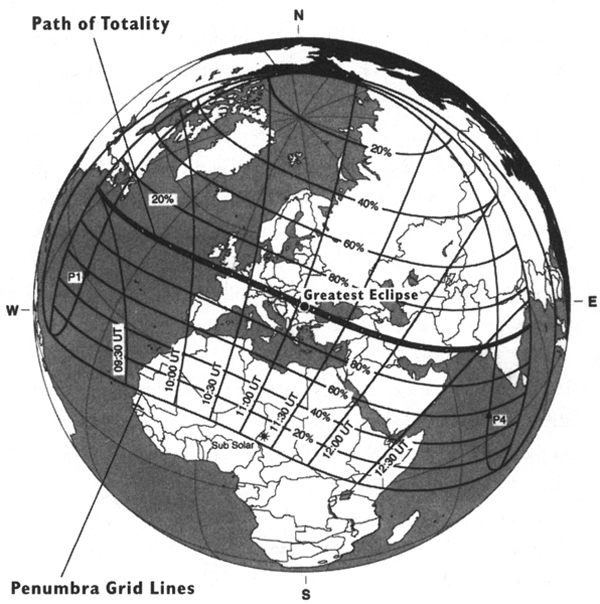

Figure 8.3 shows the view of the sky from Falmouth at the time of totality. Around the eclipsed Sun can be seen stars and planets hidden by the glare of the Sun only a few seconds before. The planets Jupiter and Saturn will be setting in the west and may be difficult to identify. However, as mentioned above, Mercury and Venus, the two inferior planets (those whose orbits are closer to the Sun than the Earth’s) should be quite easy to find. Mercury is 18° west of the Sun and Venus 15° to its east, both quite bright in the darkening sky. Venus will be shining so brightly that it will be impossible to miss it during totality. Mercury will prove much more challenging, but not too difficult if the sky transparency is good. For many people this will

Figure 8.3. View of the sky around the eclipsed Sun at Falmouth on 11 August 1999. To locate celestial objects, hold the map overhead with ‘South’pointing towards the Sun. The centre of the diagram is directly overhead; the outside rim is the horizon. be their first view of Mercury, as its orbit is very close to the Sun and it is normally difficult to observe. Under the right circumstances, it should be possible to view all five of these planets. At the time of the eclipse the Sun is in the constellation of Cancer, a region of the sky devoid of bright stars. However, bright stars which are relatively close to the eclipsed Sun include Sirius, Regulus, Castor, Pollux and Procyon.

Royal Greenwich Observatory, London

The adventurous and experienced observer may wish to look for something that is rare at any time but would be an astonishing sight during an eclipse. When the Sun’s rays have been totally obscured, it may be possible to see a meteor. The Perseid meteor shower, one of the most reliable and spectacular in the sky, reaches the peak of its activity between 10 and 12 August each year. Its radiant, the point in the sky from which the meteors appear to originate, is located about 50° above the western horizon, near the star Mirfak, which is shown in Figure 8.3. Meteors, or shooting stars as they are popularly called, are in reality tiny pieces of cosmic debris burning up as they plunge into the Earth’s atmosphere at tens of kilometres per second. In the 2 minutes 6 seconds of totality, it might just be possible to see one of these fiery tracks if it is exceptionally bright. Of course, the Perseid meteors can be seen in the night sky after the Sun sets, but it is particularly bizarre to spot one during the daytime hours.

At 11:13:21 BST the total eclipse is all over at Falmouth. This is the time of third contact, when the Moon begins to move off the Sun’s disk. The corona disappears, and eyes should be quickly protected against the harmful rays of direct sunlight streaming around the Moon’s limb.

Figure 8.4. The path of totality between England and France. The umbra engulfs Alderney, one of the Channel Islands, before making contact with the French mainland.

Royal Greenwich Observatory, London

A few minutes after the corona disappears at Falmouth, at 11:16, the umbra leaves England and quickly traverses the English Channel, as shown in Figure 8.4. London misses the total phase but experiences partiality with a maximum magnitude of 0.968 (i.e. 96.8 per cent of the Sun’s diameter will be obscured) at 11:20, when the eclipsed Sun crosses London’s local meridian. At that instant, the umbra is just about touching the French coast near Dieppe, as shown on the map.

The Channel Islands of Guernsey and Jersey lie just south of the path, and witness a partial eclipse of magnitude 0.995. To the north, Alderney is deep in the path and enjoys over one and a half minutes of totality. A large group of astronomers from the United Kingdom attending a scientific meeting on Guernsey will cruise to the island of Alderney to observe the eclipse.

The umbra then crosses the English Channel, the Cherbourg peninsula, northern France, and the southern tip of Belgium and Luxembourg, and moves on to southern Germany. After passing over Austria, Hungary and the north-eastern tip of Yugoslavia, the eclipse reaches its maximum duration of totality over Romania before crossing the north-eastern part of Bulgaria and the Black Sea.

Not since 1961 has the Moon cast its dark shadow upon central Europe. The southern edge of the umbra first reaches the Normandy coast just as the northern edge leaves England. As the shadow speeds across the French countryside, its southern edge passes 30 km north of Paris, whose inhabitants will witness a partial event of magnitude 0.992 at 11:23 BST, or 12:23 p.m. local French time.

Continuing on its eastward track, the path’s northern limit crosses into southern Belgium, Luxembourg and Germany. Stuttgart, lying near the path’s centre, has 2 minutes 17 seconds of totality. Here the Sun stands at 55° above the horizon. The path is now 109 km wide, and the ground speed has dropped to 44.4 km per minute. Although Munich lies 20 km south of the centre-line, the city’s two million citizens will still experience more than 2 minutes of totality.

Figure 8.5. The path of totality across Europe. The instant of greatest eclipse occurs at 12:03:04 BST near the Romanian capital of Bucharest.

Espenak, F. and Anderson, J., Total Solar Eclipse of 1999 August 11, NASA Reference Publication 1398 (NASA, March 1997)

The path across Europe can be followed in Figure 8.5, where the line of totality and the names of principal cities are indicated. At 11:41 BST the umbra leaves Germany and moves into Austria, where it crosses the eastern Alps. Vienna is almost 40 km north of the path and experiences a 0.990 magnitude partial eclipse. The southern edge of the path grazes north-eastern Slovenia as the shadow enters Hungary at 11:47 BST. Lake Balaton, a popular Hungarian resort, lies wholly within the path, and the umbra arrives there at 11:50 BST. Duration lasts 2 minutes 22 seconds. Like Vienna, Budapest is also about 40 km north of the path and enjoys a 0.991 magnitude partial eclipse. As the shadow leaves Hungary, it sweeps through northern Yugoslavia before continuing on into Romania.

The instant of greatest eclipse occurs at 12:03:04, when the axis of the Moon’s shadow passes closest to the centre of the Earth. At that moment the shadow’s centre is located among the rolling hills of south central Romania, very near Rîmnicu-Vîlcea as can be seen in Figure 8.6. Here the length of totality, the maximum for any point of the entire eclipse path, is 2 minutes and 23 seconds. This increase in duration is due to the increase in the ‘slowing speed’ of the shadow due to the Earth’s rotation. The slowing speed is greatest when the Moon and the eclipsed Sun are at the local meridian. A few minutes later, Romania’s capital city Bucharest is engulfed by the shadow. Continuing east– south-east, the path crosses the Romania/Bulgaria border before heading out across the Black Sea.

The next landfall occurs along the Black Sea coast of northern Turkey at 12:21 BST. For Ankara, 150 km south of the path, there is a 0.969 magnitude partial eclipse. The track diagonally bisects Turkey as it moves inland, while the duration centre-line begins a gradual but steady decrease. At 12:29 BST, Turhal falls deep within the shadow for 2 minutes 15 seconds. At just about this time, viewers in Falmouth will see the Moon finally move away from the Sun as the partial eclipse phase ends there, with fourth contact.

Figure 8.6. The path of the Moon’s umbra in the vicinity of the position of greatest eclipse, near the Romanian capital of Bucharest.

Espenak, F. and Anderson, J., Total Solar Eclipse of 1999 August 11, NASA Reference Publication 1398 (NASA, March 1997)

The umbra now reaches Turkey’s south-eastern border at 12:45 BST and briefly enters north-western Syria as it crosses into Iraq. The centre-line duration is now 2 minutes 5 seconds, with the Sun’s altitude at 50°. At Baghdad, 220 km south of the path, there is a partial eclipse of magnitude 0.940. Arriving at Iran’s western border, the shadow spends the next half-hour crossing sparsely populated mountain ranges and deserts. The inhabitants of Tehran, north of the path, will witness a 0.943 magnitude partial eclipse. At 13:22 BST the shadow enters Pakistan and skirts the shores of the Arabian Sea. Karachi is near the centre-line and experiences I minute 13 seconds of totality with the Sun 22° above the western horizon. By now the path width has shrunk to 85 km, while the shadow’s speed has increased to 120 km per minute.

The umbra arrives in India, the last nation in its path, at 13:28 BST. As the shadow sweeps across the subcontinent, its velocity rapidly increases while the duration of the eclipse on the centre-line drops to less than a minute. At this point the Sun is only 7° above the horizon. The 11 million inhabitants of Calcutta will witness a 0.879 magnitude partial eclipse with the Sun a scant 2° above the western horizon. Leaving India just north of Vishakhapatnam, the shadow sweeps into the Bay of Bengal where it moves off the Earth and back into space at exactly 13:36:23 BST, not to return until the next millennium. Over the course of 3 hours and 7 minutes, the Moon’s umbra will have travelled a path approximately 14,000 km long at an average speed of 4500 km/h, about twice the cruising speed of Concorde.

The next time an eclipse from saros series 145 returns to the Earth will be on 21 August 2017, 18 years and 10.32 days after 11 August 1999. It will be the first total solar eclipse visible from the continental United States since 1979. The path of totality in 2017 will stretch from Oregon through Idaho, Wyoming, Nebraska, Missouri, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee. The longest period of totality will be in the Carolinas, and has a duration of 2 minutes and 40 seconds.

From the twenty-first to the twenty-fourth century inclusive, Saros 145 will continue to produce total solar eclipses of increasing duration as the path of each event shifts southward. By the time the midpoint of the series is reached on 25 February 2324, the duration of totality will exceed 4 minutes. The duration continues to increase into the twenty-fifth and twenty-sixth centuries. The maximum duration of totality peaks at 7 minutes 12 seconds on 25 June 2522. In the remaining six umbral eclipses, the duration rapidly drops but is still almost 3 minutes at the final total eclipse of the series, on 9 September 2648.

Over the next three and a half centuries there will be twenty partial eclipses of progressively decreasing magnitude occuring. The final event, the 77th in the series, will take place on 17 April 3009 over the polar regions of the southern hemisphere. The saros series that produces the last eclipse of the second millennium will thus continue into the fourth millennium.

Figure 8.7. The last eclipse of the millennium.