HOW SHOULD WE GO about creating a note-by-note dish? In creating a traditional dish, some chefs begin by making sketches; others go to the market; others simply sit down and think. Any of these methods, even the second one, might work in note-by-note cooking. But let’s try sitting down—in front of an empty plate.

A plate? It may seem an oddly conventional choice considering that what we are trying to do is to imagine a truly new way of cooking. Foods are physical objects, and so they can be served in many different ways. They can, of course, be served in bowls or in cups. But they could also be suspended. Fruits, after all, hang from trees. Why couldn’t they be thrown? It was thus, after all, that God caused manna to fall from heaven. In principle, at least, there are any number of ways in which dishes can be presented. But let’s not complicate matters too quickly. Let’s start with the traditional plate and think about what we wish to put on it.

Gases, vapors, and fumes are possible candidates, at least theoretically, but the density of these substances is so slight that most gourmets will prefer liquids and solids. In the case of a liquid, the question of shape and form arises only indirectly because it is bound to assume the form of the container in which we choose to serve it. But if a food is solid, it will have the shape that we ourselves will have given it. In either case, we face the problem of deciding which shapes are most appropriate.

Unless you are a great artist—someone who, almost by definition, cannot help but surprise his audience—it would be mere laziness, if not actually childishness, to serve a dish consisting of a single object and a single shape. Unless times are very hard indeed, a breast of chicken served without sauce and something to go with it, a vegetable or a starch, is a sorry sight. A tomato with just a sprinkling of salt likewise makes a poor meal. We may well appreciate its virtues when we pause during a long day’s hiking in the mountains for something to eat, hunger having become the best of cooks, but no civilization in normal times has willingly resigned itself to so little. In both these examples, as in any number of others that may easily be imagined, the most disconcerting thing is the lack of

structure. Cooking might almost, in fact, be said to be entirely a matter of structure, in the sense that a cook whose ambition goes beyond executing a series of familiar procedures known as a “recipe” has no choice but to construct—to use his own imagination in giving a certain structure or shape or form to his dish. He will be aided in this task if he is aware that the human brain has developed the ability over millions of years of evolution to recognize contrasts and differences. When you enter a room filled with cigarette smoke, for example, you are struck at once by the odor of burned tobacco. But if you remain in a smoky room long enough, you no longer perceive the odor. The same is true for color. We are sometimes surprised when, developing film in a darkroom that is artificially illuminated by red light, everything looks red at first, then normal. The reason is that after prolonged exposure to light in which the wavelength that the eye perceives as red is predominant, we no longer see the color red. The same goes for the perception of consistencies, and also of shapes, which are what we are concerned with here.

The question of structure seldom arises in traditional cooking. Shapes are given for the most part by the ingredients themselves, and even if the cook slightly alters them by cutting and chopping and so forth, he is generally limited to assembling a series of shapes given in advance. Why have cooks been content historically to work with so few shapes? Probably because of a practical concern with wasting as little food as possible. A fish filet trimmed in the form of a slab would have been an unthinkable luxury in times of famine, when not a scrap of food was thrown away. Cooking as we know it today developed when shortages were common.

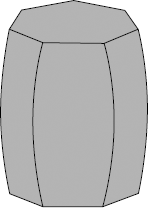

The traditional cook who nevertheless insists on creating novel forms offers proof of the affection he feels for his guests. Cutting a food into a square is a way not only of showing that he is willing to sacrifice a part of the ingredients he has purchased at more or less great cost, but also of showing that he has applied himself to the task of pleasing those who dine at his table. Thus one trusses a roast with butcher’s twine to give it a cylindrical shape or slices (or juliennes or dices) carrots instead of leaving them whole. In the case of Pommes de terre à l’anglaise, lopping off the two ends of the potato to make a log and then cutting seven sides or faces to give it the shape of a small barrel is a way of reconciling labor with economy: with seven sides, the cook has to go only to a very small amount of trouble in order to keep the loss of edible material to a minimum. Traditional cooking had the right idea. But it was handicapped by a certain conceptual stinginess, a certain lack of imagination, and failed to get very far.

The problem of structure assumes a different form in note-by-note cooking, but it is no less unavoidable: our empty plate will remain empty if we are unable to give a shape to the foods we wish to construct. How many shapes are there for us to choose from? A much larger number, as it turns out, than traditional cooking would lead us to believe. As a practical matter, the answer to our question is really quite simple: one takes a mold, which already has a shape, and fills it with a substance that will then take on the shape of the mold and retain it. From a theoretical point of view the answer is simple as well, but immensely more illuminating. Since most complex shapes can be reduced to elementary shapes, let’s examine this latter class first, beginning with so-called regular forms.

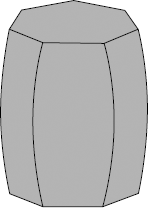

Polyhedrons are volumes enclosed by flat surfaces. Prehistoric toolmakers, for example, took an irregular piece of flint and modified it by cutting it along a flat plane so that each cut produced a smooth face. A moment’s reflection will show that a physical object cannot have only two faces, or only three. The minimum number of faces for a polyhedron is four, in which case the object is a tetrahedron. A tetrahedron can be regular, with faces that are identical, or it can be irregular. The same is true of objects with more than four faces. Furthermore, whether polyhedrons are regular or not, they can be either convex or concave.

CONVEX POLYHEDRONS

In the history of mathematics, regular convex polyhedrons occupy a special place. They were systematically studied by the Greek mathematicians of antiquity, who interpreted them as models of physical objects. The Greeks understood that although it is possible to construct an infinite number of convex polyhedrons, only five of them have faces that are regular polygons, which is to say polygons having equal sides. These objects, the so-called Platonic solids, are the tetrahedron (with four triangular faces), the cube (six square faces), the octahedron (eight triangular faces), the dodecahedron (twelve pentagonal faces), and the icosahedron (twenty triangular faces).

Our names for convex polyhedrons of all kinds, not just regular polyhedrons, are derived from Greek roots. I have just mentioned the tetrahedron (from tetra, meaning four); beyond this, there are pentahedrons, hexahedrons, heptahedrons, octahedrons, nonahedrons, decahedrons, hendecahedrons, dodecahedrons, and so on. But knowing their names will count for little so long as we remain unable to rapidly survey the universe of possible forms and then, from this very, very long list, select the ones that will fill up a plate in just the way we have in mind. Taking symmetry into account will help us sort through the most promising candidates far more efficiently.

If we look at a person’s face, for example, we see that it is symmetrical: a vertical plane passing through the nose divides the face into two roughly identical halves, reversed in relation to the plane. A plane of this sort is called a “plane of symmetry” (or a “symmetry plane”). In other cases, the relevant geometrical perspective is provided not by a plane, but by an axis. Take, for example, a prism with a triangular base—in other words, an object described by three vertical planes passing through the sides of a triangle traced on a horizontal supporting plane. If the base triangle is equilateral, with three equal angles, then the vertical axis, which passes through its center, exhibits what geometers call symmetry of order 3: rotating the prism by a third of a turn brings it back into alignment with its initial position. Rotational symmetries of order 4, 5, 6, and so on are defined in a similar fashion.

And so it is that number makes itself manifest in the world! Is it visible to us because it does in fact constitute the basis of the physical world or because our minds have been predisposed by biological evolution to find it everywhere? This is a very difficult question—but cooks, even without trying to answer it, will be able to exploit the mathematical properties (and, more generally, the cultural associations) of numbers in the kitchen. Starting from 4, the minimal number of faces of a polyhedron, we move on to 5, which is sometimes thought of as a magic number, and then to 6, whose ambivalent reputation in the popular mind is due to its role in games of chance and prophecy. I mentioned the number 7 a moment ago in connection with the seven faces of Pommes de terre à l’anglaise. Whether this number somehow minimizes both the loss of edible material and the labor required to make certain dishes, as legend would have it, it has special significance for many people: the seven basic colors, the seven days of the world’s creation, the seven pillars of wisdom, the seven days of the week, and so on. The number 7 is a mystical number for some, the symbol of perfection; and for at least one fraternal organization that comes to mind it holds greater importance than perhaps it should. Seven is also the number of chapters in this edition of my book.

From 7 we go on to 8, a symbol of happiness responsible for the congestion in town halls on the eighth day of the month in France and other countries, when many couples come to be married. The number 9 is considered to be a token of good luck, whereas 11 is linked with the idea of excess. As for 13, there is no need for any very lengthy explanation. In our culture it has a baleful connotation, and cooks, for their part, will generally want to avoid it; but if they happen to be cooking for a party of guests for whom 13 is a propitious number, there is no reason not to use it in selecting the shapes of various dishes. Is this mere opportunism? No doubt it is, at least to some extent. Still, even if the cook is imagined to be a simple, naive soul who is in the habit of choosing the shapes of the food he makes on the basis of his own numerological whims and prejudices, what harm is there in his trying from time to time to add to the happiness of the people he feeds by catering to theirs?

CONVEXITY AND CONCAVITY

This exceedingly rapid tour of polyhedrons would not be complete without saying a word or two about convexity and concavity. Why are some objects pointed or protruding, and others hollow? One hardly needs to be preoccupied by sex in order to think in the first place of the complementarity of masculine and feminine. But there is also the relation between container and contained. Thus a concave polyhedron can accommodate either a liquid or a solid substance. What is more, a hollow object that is open on one side can be sealed or closed up, which suggests to the mind of a cook the idea of stuffing foods inside one another—a way of surprising the person to whom they are served.

Which form should we prefer, concave or convex? Consider the difference between the English place setting, where the fork is placed with its tines upward, and the French place setting, where the fork is placed with its tines downward. The choice in this case conceals a question of politeness having to do with one person’s sympathetic concern for the psychological and physical comfort of others: a fork placed in the English manner confronts the person across the table with a set of sharp, menacing prongs, whereas the same fork, turned face down, presents a softer, more rounded aspect. Again, as a matter of courtesy, the blade of the knife is customarily turned toward the plate, and not outward in the direction of the person sitting next to us.

Showing concern for those who dine at our table is not merely a detail of etiquette, however. It is a form of conviviality in the literal sense of the term. From the geometrical point of view, the cook must take care not to take too pointed an interest, shall we say, in the sensibilities of his guests. Apices and convex polyhedrons should not be banned from the repertoire of admissible culinary forms, of course—but only on the condition that all the rough edges have been smoothed out!

Another, more rounded class of shapes that recommends itself to the cook’s consideration includes the sphere, the cylinder with a circular base, the cone. Mathematicians have exhaustively studied all of these solids. In all of them, the idea of symmetry is essential.

ROTATIONAL SYMMETRY

Spheres, cylinders, and cones are members of a family of shapes that exhibit rotational symmetry; that is, they are produced by rotation around an axis, without undergoing any alteration of shape. A sphere is produced by the rotation of a semicircle around an axis passing through the center of this semicircle. A cylinder exhibiting rotational symmetry is produced by turning a rectangle around one of its edges. A cone is likewise the result of rotating a triangle. Other solids can be obtained by rotation as well. Most bottles, for example, exhibit rotational symmetry around their axis. Pottery made on a potter’s wheel displays the same property.

All these objects have a pleasing roundness, long appreciated not only by architects and interior designers, but also by sculptors, stoneworkers, and furniture makers. Today more than ever, with the advent of note-by-note cooking, cooks will profit from the example of these and other craftsmen, whose ancestors were not given shapes to work with in advance—the shape of a tenderloin of beef, for example, or a breast of chicken or a filet of fish. They had to learn which shapes were most suitable for their work. Their knowledge and experience can now be imported into cooking.

OTHER FORMS OF SYMMETRY

Shapes produced by rotation around an axis are by no means the only possible symmetrical forms. Many living creatures are more or less symmetrical, but their symmetry is not due to rotation. A fish, for example, is roughly symmetrical in relation to a plane. An idealized starfish, with its five arms, has a symmetry (of order 5) in relation to an axis perpendicular to the plane of the arms. One thinks, too, of star fruit (carambola or Chinese gooseberry) and the inflorescence of a sunflower, both of which exhibit a symmetry that is more difficult to recognize—also of squashes that have several lobes and of winter squash and pumpkins, which have a larger number of lobes more or less evenly distributed around an axis.

A whole book could be written about symmetries—indeed, many such books already have been written. I shall limit myself here to observing that symmetry, in the world in which we actually live, is an unattainable ideal: our faces are not composed of two absolutely symmetrical halves in relation to the nose; more generally, shapes that appear at first sight to be perfectly balanced are marred by a slight departure from symmetry, even if our brains usually manage to cope with the imperfection readily enough. It is, after all, an old painter’s trick to introduce a slight asymmetry just where the mind expects to find symmetry. This little blemish is what makes formal perfection—which Nietzsche rightly saw as poisonous and inimical to life—human and loveable. In cooking no less than in many fields of endeavor, not only painting and the other arts but also the sciences, even the worlds of administration and commerce, we are well advised, I believe, to tolerate some small degree of imperfection lest we become inhuman.

WHEN SYMMETRY DISAPPEARS

Cooks should therefore be guided by the simplicity found in symmetry. But they mustn’t neglect complexity, because the human mind perpetually hesitates between the two. Nevertheless cooks should not be interested in complexity for its own sake—too much of it and their creations will be incomprehensible. In my book with Pierre Gagnaire, I proposed (unwisely, perhaps, since when it comes to art we should be wary of rules) that art can be appreciated only if it introduces a limited and controlled sort of novelty into a composition whose elements are for the most part recognizable and familiar to us. It will therefore be to the artist’s advantage to slightly deform or distort the known and the familiar, whether he is dealing with a geometric shape or an abstract “form.”

Why the scare quotes around the last word? Because even though we are concerned primarily with geometry here, it is impossible to resist the temptation to venture a useful generalization involving Platonic forms—the name Plato gave to objects of intelligible (rather than visible) reality, objects of pure knowledge. In this sense, one may speak of the Orangeness of oranges, the Bitterness of beer, the Freshness of mint, the Spiciness of pepper, and so on. These capitalized nouns refer to ideal archetypes, of which the actual objects we know from firsthand experience are regarded as so many inferior copies. I am well aware, of course, that most gourmets will balk at the suggestion that in the realm of odors, for example, there exists an ideal Vanilla odor. They know that no two neighboring pods of vanilla in a market smell the same; indeed, chemical analysis of the constituent compounds confirms that they differ very slightly. We ought, then, to speak instead of the various odors of vanilla, not of Vanilla as an archetypal odor. The same is true for oranges, whose fragrance cannot be reduced to the olfactory effect of a compound called limonene, any more than the smell of Roquefort can be reduced to the effect of heptanone. Or, again, considering the matter from the standpoint of color: the yellow plum known in France by the name “mirabelle” displays a variety of yellows in addition to shades of orange and red. Similarly, with respect to taste, different kinds of beer display different kinds of bitterness (just as their color may vary from blond to dark over a range of shades); with respect to trigeminal sensations, different kinds of mint (peppermint, pennyroyal, bergamot, spearmint, wild mint, and so on) display different kinds of freshness, and different kinds of pepper (from Madagascar, Szechuan, Sarawak, and many other places) display different kinds of spiciness.

Cooks will nonetheless gain new insight if they keep in mind the similarities, rather than the differences, between these qualities, for they will then be able to take advantage of the brain’s innate tendency to detect general properties—geometric forms, olfactory forms, sapid forms, and so on—in creating new dishes. A gifted cook can season a sauce with tarragon, for example, so very slightly that the herb’s aroma is not obvious: the gourmet tastes, smells something, and begins to wonder. “What’s that flavor? Could it be [chews pensively], or perhaps [thinks a bit more]…?” And then suddenly it hits him: “Tarragon!” Surely the same effect could be exploited in the case of both geometric shapes and abstract forms, but only so long as cooks are acquainted with all those solids that do not display symmetry—much more numerous, as it happens, than the ones that do.

How are we to begin hacking our way through this jungle? By putting the resources of topology to work. Topology is a branch of mathematics that contemplates objects as though they were made of modeling clay—as though they were capable, in other words, of being deformed, though not to the point of being torn. From this point of view, a ball and a cube are topologically equivalent. Think of the ball as an egg yolk that has been cooked at 67°C (153°F) until it assumes the consistency of an ointment, so that it is malleable while yet conserving the color and taste of a fresh egg, and you will see at once that it can be made into a cube.

Topology classifies objects by the number of holes they have. A coffee cup, for example, is topologically equivalent to a doughnut or a rubber tire or a simple knot: all of these things have one hole, as you can easily see by playing with modeling clay yourself. Eyeglasses have two holes before they have been fitted with lenses, however, and so are not equivalent to coffee cups. None of this tells us which shapes we should choose, of course. But it does help us to think more clearly and to get our bearings in an infinite universe of possibilities.

The problem of choosing culinary forms will become somewhat more tractable if we remember that painting, sculpture, music, and the other arts have often imitated nature. Why they have imitated nature and whether imitating nature is a good thing are questions that do not concern us for the moment. What matters is that artists have seldom tried to reproduce nature exactly. Instead they have sought to give both a personal vision and, even more important, a cultural interpretation of it. In the Middle Ages, for example, rather than make objects and figures in the foreground larger than the ones in the background, painters scaled them in a way that corresponded to their cultural significance or social prominence.

Did the formulation of rules of perspective in Florence in the fifteenth century represent a step forward? Certainly they provided painting with a technique that until then had been beyond its reach and that enabled it to draw ever nearer to the precision that photography was later to achieve. But should art concern itself mainly with exact reproduction? For that purpose, surely, reality itself will do. If art seeks above all to arouse emotion, however, the rules of linear perspective represent a step backward, one that Picasso and other painters of his generation adamantly refused to take.

In the art of cooking, social ties and the personal experience of sharing count for more than anything else. This is why, ultimately, I prefer to examine the problem of culinary structure in terms of purpose or intent. What is the cook trying to do? Many things—but in the first place he or she is trying to fill a plate with shapes that will provoke an emotional response from his guests. How shall the culinary artist decide which shapes are best suited to this purpose? This is the basic question that we must deal with at the very outset. It goes to the heart of the mystery of artistic creation, which may be expressed in the form of another question: How is it that a great artist’s work comes to be admired by people in every country and in every age despite the mutable nature of personal tastes?

A poetic answer to this second, still more fundamental question is given in a fable by Alphonse Daudet (written in collaboration with Paul Arène) that first appeared in his collection Lettres de mon moulin (Letters from My Mill, 1869). To “the Lady who asks for light-hearted stories,” Daudet replies with these words:

On reading your letter, madame, I had a feeling of remorse. I was angry with myself for the rather too doleful color of my stories, and I am determined to offer you today something joyous, yes, wildly joyous.

For why should I be melancholy, after all? I live a thousand leagues from Parisian fogs, on a hill bathed in light, in the land of tambourines and Muscat wine. About me everything is sunshine and music; I have orchestras of finches, choruses of tomtits; in the morning the curlews say: “Cureli! cureli!”; at noon, the grasshoppers; and then, the shepherds playing their fifes, and the lovely dark-faced girls whom I hear laughing among the vines. In truth, the spot is ill-chosen to paint in black; I ought rather to send to the ladies rose-colored poems and baskets full of love-tales.

But no! I am still too near Paris. Every day, even among my pines, the capital splashes me with its melancholy. At the very hour that I write these lines, I learn of the wretched death of Charles Barbara, and my mill is in total mourning. Adieu, curlews and grasshoppers! I have now no heart for gayety. And that is why, madame, instead of the pretty, jesting story that I had determined to tell you, you will have again today a melancholy legend.

Once upon a time there was man who had a golden brain; yes, madame, a golden brain. When he came into the world, the doctors thought that the child would not live, his head was so heavy and his brain so immeasurably large. He did live, however, and grew in the sunlight like a fine olive tree; but his great head always led him astray, and it was heartrending to see him collide with the furniture as he walked. Often he fell. One day he rolled down a flight of stairs and struck his forehead against a marble step, upon which his skull rang like a metal bar. They thought that he was dead; but on lifting him up, they found only a slight wound, with two or three drops of gold among his fair hair. Thus it was that his parents first learned that the child had a golden brain.

The thing was kept secret; the poor little fellow himself suspected nothing. From time to time he asked why they no longer allowed him to run about in front of the gate, with the children in the street.

“Because they would steal you, my lovely treasure!” his mother replied.

Thereupon the little fellow was terribly afraid of being stolen; he went back to his lonely play, without a word, and stumbled heavily from one room to another.

Not until he was eighteen years old did his parents disclose to him the monstrous gift that he owed to destiny; and as they had educated and supported him until then, they asked him, in return, for a little of his gold. The child did not hesitate; on the instant—how? by what means? the legend does not say—he tore from his brain a piece of solid gold as big as a nut, and proudly tossed it upon his mother’s knees. Then, dazzled by the wealth that he bore in his head, mad with desires, drunken with his power, he left his father’s house and went out into the world, squandering his treasure.

From the pace at which he lived, like a prince, sowing gold without counting, one would have said that his brain was inexhaustible. It did become exhausted, however, and little by little one could see his eyes grow dull, his cheeks become more and more hollow. At last, one morning, after a wild debauch, the unfortunate fellow, alone among the remnants of the feast and the paling candles, was alarmed at the enormous breach he had already made in his ingot; it was high time to stop.

Thenceforth he led a new kind of life. The man with the golden brain went off to live apart, working with his hands, suspicious and timid as a miser, shunning temptations, trying to forget, himself, that fatal wealth which he was determined never to touch again. Unfortunately, a friend followed him into the solitude and that friend knew his secret.

One night the poor man was awakened with a start by a pain in his head, a frightful pain. He sprang out of bed in deadly alarm, and saw by the moonlight his friend running away, with something hidden under his cloak. Another piece of his brain stolen from him!

Some time afterward, the man with the golden brain fell in love, and then it was all over. He loved with his whole heart a little fair-haired woman, who loved him well too, but who preferred her ribbons and her white feather and the pretty little bronze tassels tapping the sides of her boots.

In the hands of that dainty creature, half bird and half doll, the gold pieces melted merrily away. She had every sort of caprice; and he could never say no; indeed, for fear of causing her pain, he concealed from her to the end the sad secret of his fortune.

“We must be very rich,” she would say.

And the poor man would answer:

“Oh, yes! very rich!” and he would smile fondly at the little bluebird that was innocently consuming his brain. Sometimes, however, fear seized him; and he longed again to be a miser; but then the little woman would come hopping towards him and say:

“Come, my husband, you are so rich, buy me something very costly.”

And he would buy something very costly.

This state of affairs lasted two years; then, one morning, the little woman died, no one knew why, like a bird. The treasure was almost exhausted; with what remained the widower provided a grand funeral for his dear dead wife. Bells clanging, heavy coaches draped in black, plumed horses, silver tears on the velvet—nothing seemed too fine to him. What mattered his gold to him now? He gave some to the church, to the bearers, to the women who sold immortelles; he gave it on all sides, without bargaining. So that, when he left the cemetery, almost nothing was left of that marvelous brain, save a few tiny pieces on the walls of his skull.

The people saw him wandering through the streets, with a wild expression, his hands before him, stumbling like a drunken man. At night at the hour when the shops were lighted, he halted in front of a large shop window in which a bewildering mass of fabrics and jewels glittered in the light, and he stood there a long while gazing at two blue satin boots bordered with swan’s-down. “I know someone to whom those boots would give great pleasure,” he said to himself with a smile; and, already forgetting that the little woman was dead, he went in to buy them.

From the back of her shop the dealer heard a loud outcry; she ran to the spot, and recoiled in terror at sight of a man leaning against the window and gazing at her sorrowfully with a dazed look. He held in one hand the blue boots trimmed with swan’s-down, and held out to her the other hand, bleeding, with scrapings of gold on the ends of the nails.

Such, madame, is the legend of the man with the golden brain.

Although it has the aspect of a fanciful tale, it is true from beginning to end. There are in this world many poor fellows who are contented to live on their brains, and who pay in refined gold, with their marrow and their substance, for the most trivial things of life. It is to them a pain recurring every day; and then, when they are weary of suffering….

Alas, my dear cooks, it may be thus that you will decide which shapes to assemble on a plate in order to give form to a dish that you yourself will have constructed: by extracting all the gold there is in your brains—and this at the risk of great suffering, even of death. Out of love for those whom you have invited to dine at your table, you dare to exhaust your own most precious resources in seeking to recover nuggets of artistic truth—your truth, the product of your deepest feeling and emotion.

Some may feel that a book that aspires to inaugurate a new way of cooking should be wary of starting out on such a gloomy note. After all, a fable is just that—a fable. Against the dark melancholy of Daudet’s windmill, plunged into mourning by Barbara’s death, let us therefore set the luminous prospect of the birth of a truly new cuisine. My sisters, my brothers, all of you who are cooks, if you are true artists, your spirit will speak through your creations. And in giving voice to your spirit, you shall have achieved your supreme purpose as a human being, by sharing yourself, your ideas, your passions, your innermost longings with all those who are dear to you.

Berggren, Lennart, Jonathan Borwein, and Peter Borwein, eds. Pi: A Source Book. 3rd ed. New York: Springer, 2010.

Coxeter, H. M. S. Regular Polytopes. 3rd ed. New York: Dover, 1973.

Neugebauer, Otto. The Exact Sciences in Antiquity. 2nd ed. New York: Dover, 1969.

This, Hervé, and Pierre Gagnaire. “Thomas Aquinas and the Green of the Grass.” In Cooking: The Quintessential Art, translated by M. B. DeBevoise, 166–178. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008.

Zee, A. Fearful Symmetry: The Search for Beauty in Modern Physics. 3rd ed. With a foreword by Roger Penrose. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2007.