A cocktail made of water, ethanol (about 35 percent), citric acid, glucose, sucrose, tartaric acid, and artificial blueberry flavoring. The mixture is put in individual soda siphons, placed under pressure using carbon dioxide, and dispensed directly from the siphons into serving glasses. First served at a dinner sponsored by the Quebec Institute for Tourism and Hotels in Montreal, April 11, 2012.

Made with coagulated fish proteins, triglycerides (oil can be substituted), amylose and amylopectin (otherwise corn starch), brilliant blue (the blue pigment found in Curaçao, for example), glucose, salt, piperine (alternatively, pepper that has been macerated in oil), and compounds that impart a sensation of freshness (cooks may use what the food industry calls “coolers,” for example, or fresh cucumbers macerated in water and oil). Montreal, April 11, 2012.

Molecular cooking has sometimes been criticized for its use of “soft” products, in particular gels, but this is due to a misunderstanding. All meat and vegetables are gels, consisting as they do of water trapped in a solid; moreover, traditional and molecular cooks alike can make whatever soft or hard products they need. Here the hard, glassy top part was made from isomalt and placed on top of a red base made from wheat proteins. Montreal, April 11, 2012.

This dish—made from gluten, which is not, strictly speaking, a pure compound, but rather a mixture of wheat proteins—is an example of “practical” (rather than “pure”) note-by-note cooking. It may be likened to using a synthesizer rather than a computer to make musical sounds. Artificial color, flavor, and odor are added to the gluten once it has been cooked. The glassy, green element is made of isomalt, colored with a green pigment, with flavor and odor added as well. Montreal, April 11, 2012.

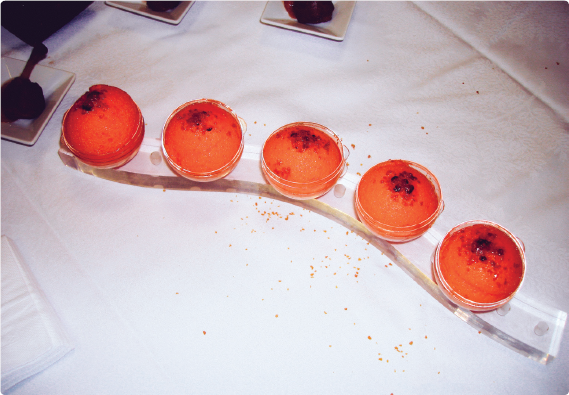

A dessert consisting of five different layers, prepared by Jean-François Deguignet, chef-instructor at L’École Le Cordon Bleu Paris and served as part of an annual dinner for students of the Institute for Advanced Studies in Gastronomy (IASG) held at the Cordon Bleu. It was made using a blue pigment, of course, but also with a number of other compounds that are officially classified as food additives. The flavor is rather like strawberry. Paris, October 15, 2011.

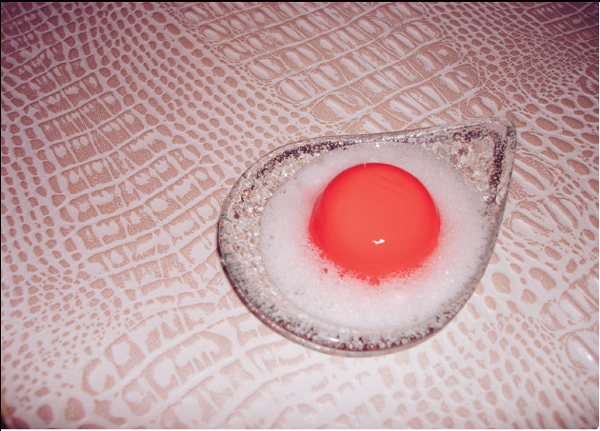

This is not an egg dish, however much it may resemble an Oeuf en meurette. The confusion was deliberate and gave rise to an amusing discussion among the guests at the 2011 IASG/Cordon Bleu dinner, who found the sauce to be quite acidic. In fact, the level of acidity is less than that of an ordinary salad dressing, but the guests had anticipated an egg flavor that was not present. Paris, October 15, 2011.

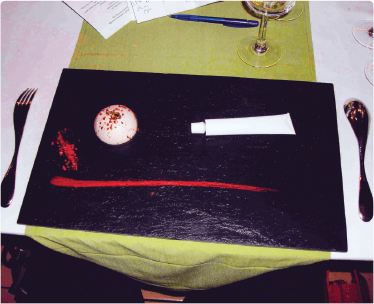

A dessert first served at the 2010 IASG/Cordon Bleu dinner. The “macaroon” on the left was made using egg proteins, sucrose, and tartaric acid. In the tube on the right, a red emulsion was prepared from cocoa butter, orange powder, and lecithin. Paris, October 16, 2010.

Chef Patrick Terrien and members of the team that prepared the note-by-note menu for the 2012 IASG/Cordon Bleu dinner. Paris, October 20, 2012.

Veal tongue fibers were mixed with turnip cellulose and arranged on a spatula with alternating layers of fatty and lean matter. The composition was then solidified with egg ovalbumin, oil, veal stock that had been slowly reduced (to hydrolyze proteins and make amino acids), citric acid, and polyphenols from the juice of Syrah grapes. Paris, October 20, 2012.

This miniature version of a commercially produced French cheese was made from milk powder, yogurt powder, iota- and kappa-carrageenan, and salt. Dipped first in a bath of water, red colorant, and iota-carrageenan, then served on a foam made with milk powder and lecithin. Paris, October 20, 2012.

The strawberry tart is a traditional dessert, sometimes served with lemon cream. In this version, devised by Chef Jean-François Deguignet, all the ingredients (except the strawberry powder) are pure compounds: lecithin, citric acid, glucose, sucrose, amylopectin, calcium lactate, water, sodium alginate, agar-agar, carrageenan. Paris, October 15, 2011.

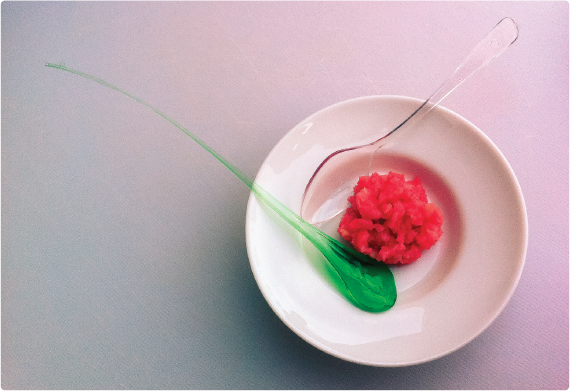

Prepared by chefs of the Paris chapter of Les Toques Blanches for the chapter’s 2011 Telethon, under the supervision of Chef Jean-Pierre Lepeltier, the dish consists of a salty aqueous solution with red colorant, ethanol, tomato powder, tartaric acid, and glucose. The green leaf on top is made of isomalt. Paris, December 3, 2011.

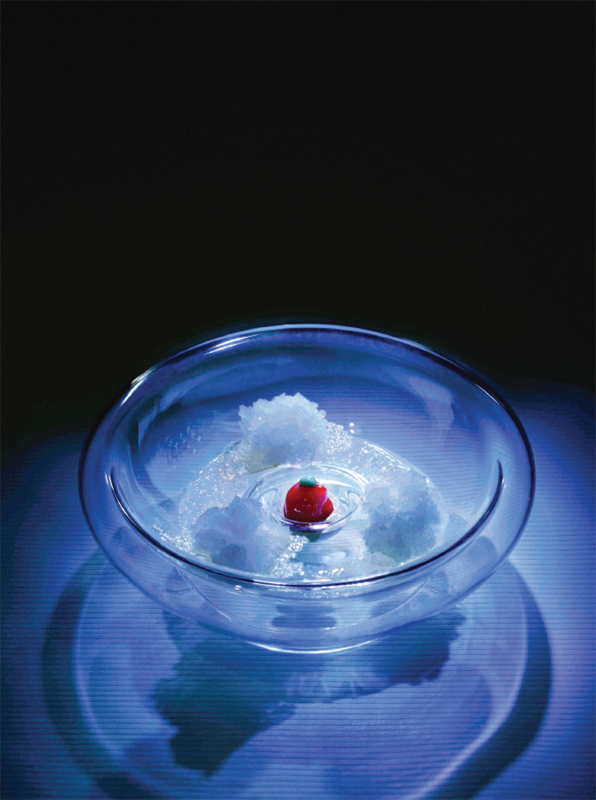

The first note-by-note dish ever served in a restaurant, by Pierre Gagnaire. The bottom part consists of alginate pearls containing a mixture of water, ethanol, salt, glucose, glycerol, and tartaric acid. It lies beneath a series of five glucose péligot disks (similar to caramel), topped by sherbet. Hong Kong, April 24, 2009.

A dessert made by the chefs Jean-Pierre Lepeltier (Hôtel Renaissance Paris La Défense), Michaël Foubert (Hôtel Renaissance Paris Arc de Triomphe), Lucille Bouche (Hôtel Renaissance Paris Trocadéro), and Laurent Renouf (Hôtel Renaissance Paris La Défense) for the dinner held at AgroParisTech in September 2012 to mark the publication of the French edition of this book. An actual chicken bone is encased in a mixture including proteins, ethanol, water, oil, tomato extract, and sucrose. Paris, September 12, 2012.

A dish conceived by the chefs Julien Lasry (Hôtel Renaissance Paris La Défense) and Jean-Pierre Lepeltier. The “bun” of these minihamburgers is made from amylopectin, ovalbumin, salt, and water. The “meat” is made from water, egg proteins (but any coagulating protein could be used), cellulose, and a number of flavoring ingredients. Paris, September 20, 2012.

A fiery appetizer created by Chef Laurent Renouf consisting of orange-colored flattened foam spheres, set alight with a mixture of ethanol and water. Served as a flaming dessert, it includes sucrose. Paris, September 20, 2012.

First served by Chef Lucille Bouche, these tarts (bouchées) were made by cooking a mixture of roasted amylopectin, ovalbumin, and water in triglycerides (otherwise in oil) for 10 minutes. The soft white “ball” placed on top is made from yogurt powder, milk powder, iota-carrageenan, and agar-agar. Paris, September 20, 2012.

Many of the gelling agents first introduced by molecular cooking (in this case sodium alginate) can be used in note-by-note cooking as well. Most traditional food ingredients are gels—plant or animal tissues in which water is trapped in a solid. The dish shown here was served as part of the 2012 IASG/Cordon Bleu dinner. Paris, October 20, 2012.

Natural oranges are made of many small vesicles (or sacs) of juice “glued” together and enclosed by a skin. Here we have small artificial pearls made from water, citric acid, and sugar and enclosed by a skin obtained by gelling sodium alginate with calcium salts. In this case, the procedure for making pearls was reversed: calcium was dissolved in the artificial juice, and then sodium alginate was dissolved in water to which this juice had been added, drop by drop; next, the pearls were collected and “glued” together using gelatin in which limonene and citral had been dispersed. I refer to all such systems as “conglomèles.”

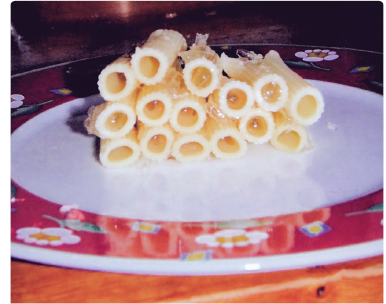

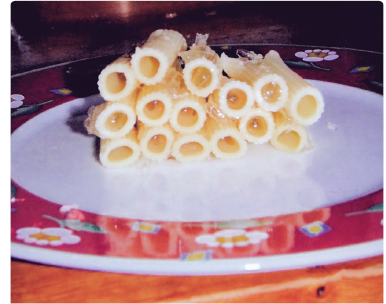

Artificial meat can be obtained by growing living cells, but the fact that meat consists of fibers connected by collagenous tissue suggests another method. The hollow tubes pictured here are made of fibers containing water and proteins and connected to one another by collagen molecules dispersed in water, just as in animal muscle tissue. I call all such examples of artificial meat “fibrés.”