9

MUTANTS, MONSTERS, AND MORPHOGENESIS

Back to the Facts

If I lived twenty more years, and was able to work, I should have to modify the Origin, and how much the view on all points would have to be modified!

CHARLES DARWIN, ORIGIN, POSTMORTEM EDITION

THE WORM WHO WOULD BE MAN

That creatures respond, adapt, and adjust to their environment in certain ways is, I would think, a given—nothing new or profound there—and nothing so trenchant as to demystify our origins, indeed nothing “more than a statement of the obvious,” as far as author Francis Hitching is concerned.1 Empedocles of the fifth century BCE, as well as other classical Greeks, wrote about it. Darwin did not invent it or discover it.

In fact once he realized the weakness of natural selection, he actually moved away from it, preferring to pitch sexual selection; between the time of Origin (1859) and Descent (1871), Darwin switched from natural to sexual selection, the latter entailing competition among males for females. The human acquisition of a beard, for example, was presumably by sexual selection, an “ornament to charm the opposite sex.” Darwin’s concept of sexual selection was used even to define the races: selection, guided by tribal standards of beauty, would set the pace for morphological change. The sexually attractive feature would confer a higher reproductive rate on its owner, and hence eventually become incorporated in the race as a whole.

But this was overplayed, if not completely misguided. We know, for instance, that even though male bustards can impress females with their flashing feathers, this extravagance has its cost: scientists have found the most flamboyant master cocks, in fact, produce a greater amount of abnormal sperm. It has also been found that among the red deer of Scotland, the most prolific males sired daughters who had fewer offspring.

As for early humans, there was probably little competition for females among Au (Au. afarensis) males.2 In fact, sexual selection seems to work for only a few animals and none of the plants. Biologists have asked: If it really did alter the species, wouldn’t everyone be bright colored or fancy feathered in a few generations? Sometimes, too, the darn hens are not even watching the male display; even vividly colored male fish are not seen by the females whose eggs he fertilizes.

It has also been argued that fighting between males does not confer any special advantage on the winner; the “loser” simply goes elsewhere to mate. Often enough the female will mate, willy nilly, with the loser. The vanquished male, moreover, may have as many offspring as the “victor.”

Some theorists have objected to this business of sexual selection as little more than a set of out-dated male assumptions, Victorian values (masculine bias) masquerading as science. In “deep thought, reason, and imagination,” thought Darwin, the male of our species attains a “higher eminence,” while women’s faculties conform more with “the lower races.”3

Earnest Hooton, for his part, refuted Darwin’s argument that sexual selection led to hairlessness; in most species, Darwin had surmised, the less hairy female, with greater exposure of naked skin, constituted a special sexual attraction. But Hooton concluded “there are few indications that preferential mating could have brought about such profound modifications in the amounts of body hair.”4 Darwin had gone so far as to explain human language, beginning with the cries and gestures of animals, as developing out of the emotional stress of courtship—the sweeter voices of females having been acquired to attract the males! (Later in this chapter we’ll take a more realistic look at the origin of language.)

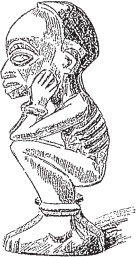

Figure 9.1. Harvard physical anthropologist Earnest Hooton was also a cartoonist and author of science fiction under a pseudonym.

Do not suffer thy judgment to mislead thee as to a law of Selection. There is no law of Selection.

OAHSPE, BOOK OF APOLLO 3:6

The ultimate question is: Could the process of natural or sexual selection or any other imagined mechanism really change things enough to produce an entirely new species? Or even a new genus? That animals can change and turn into other animals seems a bit more like magical thinking than any part of science.

Each species develops according to its own kind.

LUCRETIUS, ON THE NATURE OF THE UNIVERSE

Isn’t it interesting that natural selection, held as the key to the evolution of species in the wild, was so influenced by artificial selection as directed by human agents—animal and plant breeders, who hybridized preferred types by, of course, mixing! How ironic, since Darwin himself emphatically rejected the mixing (crossbreeding) model as an explanation of the varieties of men and animals. Here I might add, his own expertise was in the diversity of living animals and organisms—not man, and not early man. Darwin was a world expert on barnacles (he devoted eight full years to documenting their minute anatomical variations) and quite the master of beetles, pigeons, and earthworms. The worm who would one day be a man.

All right, natural selection is valid enough for minor changes, say, in the case of disease-thwarting genes against malaria, or smallpox, or when insects develop resistance to pesticides. But is that evolution or just modification? Sure, people of the Andes and Tibet have adapted to thin air with larger hearts and lungs and a greater volume of blood. Is that evolution? Whatever it is, it’s not speciation.

Also in the Andes, the llama once had five toes (10 kya); now it has two. Is that evolution? The llama has not changed to a different species! So what, if natural selection is the mechanism that changes the coat color of mice: they’re still mice. Enthusiasts find small differences in the wing shape of birds and call it “evolution in action.” No, it is modification in action. Horizontal changes only. They’re still birds.

We think of natural selection as tuning the piano, not as composing the melodies.

JERRY FODOR AND MASSIMO PIATTELLI-PALMARINI, WHAT DARWIN GOT WRONG

All such changes are horizontal, which is to say: DNA is encoded for changes only within the range of that species (there are limits, as discussed elsewhere). The genome is a conservative thing, not innovative. Indeed, DNA is structured to prevent vertical variation. In light of these well-known facts, it is not unusual nowadays to hear the top people confess “that early evolution was driven by forces very different to those we usually associate with natural selection.”5

But what are these forces? Here’s where the fudging begins: We are told, for example, that it is a recombination of factors that exist in the gene pool, or repatterning of the genotype, or genetic drift that accounts for random changes in the proportion of genes. Grasping at straws, these formulas are makeshift at best.

In the 1980s, British-Australian biochemist Michael Denton mounted an incisive case against the “implausibility of selectionist explanations.” This brilliant molecular biologist makes mincemeat of Darwinism’s imagined phylogeny, which he suggests is on a par with “medieval astrology.”6

No, I don’t think the orangutan ever held the “potentiality . . . [of] becoming man,”7 nor does the worm “strive to be man,” as Ralph Waldo Emerson mused in a moment of poetic madness. The idea that we ultimately descend from a wood louse or insectivore sounds, to one critic, like “a Kafkaesque joke.”8

Some critics say the supposed evolution of complex structures—from flagellum of bacteria to the human eye—is mathematically impossible. The eye, to England’s William Paley, was a designed instrument, like a telescope. Darwin himself, who admired Paley’s writing, owned that “to suppose that the eye with all its inimitable contrivances . . . could have been formed by natural selection, seems I freely confess, absurd in the highest degree.”9 Even his great American admirer the Harvard botanist Asa Gray thought that Darwin was unable to explain the eye by natural selection: How could “the eye, though it came to see, not be designed [e.a.] for seeing?”10 One mathematician argued that there was insufficient time for the number of mutations apparently needed to make an eye. Another mathematician has said that a simple adaptive change involving only six mutations could not occur by chance in less than a billion years. In fact “the probability of evolution by mutation and natural selection is inconceivable.” The odds of the eye evolving by chance are ten billion to one.11 When testing this possibility on computer programs, “it just jams . . . [indicating] zero probability.”12

ENVIRONMENTAL DETERMINISM: PULLING THE CLIMATE CARD

Nature does not seem to have achieved any significant modifications of existing hominid species.

JEFFREY GOODMAN, THE GENESIS MYSTERY

With nothing else—other than Divine Power—to explain the wonderful differences between species, environment then became anointed as the god of change. Pulling the climate card, theory now tells us that human evolution, occurring in Africa, was caused by major aridification: men evolved in adaptive response to the drying out of forest land and the subsequent appearance of savanna land. The whole argument is based on the assumption that man evolved in response to a drying Africa (see chapter 11). But since such different groups as Neanderthal and early Homo sapiens overlap in time and space, it became harder to explain their differences according to climate—considering their shared environment.

It has also been pointed out that, rather than adapt to drastic environmental changes, species tend to move away in search of a habitat like the one they were in. The fact that animals usually choose their habitats and flee from inhospitable environments (those all-powerful selective pressures) just about “pulls the rug from under the whole Darwinian hypothesis of natural selection.”13 Creatures like to investigate their surroundings, changes arising not from the selective pressure of the environment, but from the initiative of the living organism.14

Despite all the damning evidence trouncing natural selection, boilerplate explanations still abound—improvisation at its best. Neanderthaloid prognathism, for example, evolved because it “kept cold air away from the brain.”15 Only a few problems here: (1) cold climate cannot account for Neanderthal’s sloped forehead, chinlessness, large browridge, retromolar gap, and round eyes; (2) The German Neanderthals living in the Valley of the Ilm “enjoyed a warmer climate than now.”16 This adaptation business is “pure speculation . . . the famous Neanderthals of Krapina, in Croatia, actually enjoyed a pleasant climate.”17 As did the Neanderthals in the Near East and North Africa.

The environment plays only a very limited role in the actual creation of new genetic variants.

AARON G. FILLER, THE UPRIGHT APE

What about the assumption that people like the Inuit developed bulky bodies and short limbs to help conserve heat, thus properly adapting to a cold environment? I would argue, though, that length of limbs, like stature, is quite simply an inherited trait. Short legs are the unmistakable legacy from early man. And since the Inuit were probably the last arrivals to Native America, they came on the scene (less than 12 kya) looking rather as they do today.

If, as the evolutionary argument runs, short and stocky Neanderthal got that way due to a cold climate, why then are northern Europeans (in the coldest clime) long legged, tall, and slim? And if taller is better suited to heat, why are the northern Mongoloids taller than the southern ones? The first H. sapiens in Europe, it is argued (to smooth away the contradiction), were slimmer than Neanderthal because they had previously adapted to the warmer climates of the Mideast and Africa. The alternative explanation, of course, is inheritance: gracile AMH genes made them so.

The climate card also cranks out a case for “cold-adapted” Mongolian features (like the broad noses), even though many Asian races live and lived in hot and moist tropics. In Europe, as one moves north, noses actually narrow (rather than broaden, as theory predicts). Scandinavians have small, narrow noses. So do the Inuit. I guess they weren’t around when evolution was happening.

The races of man, in short, give no evidence that differences in nose form have anything whatever to do with cold air. Why do the little white monkeys, adapted to China’s coldest region, have such cute tiny, turned-up, snub noses? It is the opinion of some, moreover, that a smaller nose is actually more adaptive to cold—to reduce the risk of frostbite! At all events, the wide Neanderthal nose would not really heat incoming air, it would dissipate it. And with all this evidence piling up against Neanderthal’s “specialized” snoot, anthropologists are saying, yeah, we were wrong about the “radiator” nose, it was probably just a trait inherited from their ancestors. Back to square one.

Along the same lines, William Howells suggested that large-bodied, big-headed people in the western Pacific must be “the result of a little natural selection . . . [given] the constant cooling breezes that blew from the open Pacific over the islands of Polynesia . . . [whereby] loss of body heat could be a serious matter. Large bodies have a relatively smaller surface-to-bulk ratio, so that heat preservation . . . is better.”*114 18

The same school of extemporizing submits that exertion under the tropical sun led to reduction of body hair; yet man’s “peculiar larval nakedness is difficult to explain on survival principles,”19 and the loss of a hairy covering is actually disadvantageous, even in the tropics, since it exposes the body to the scorching sun. “It is improbable that this denudation could have come about through natural selection . . . there is no appreciable relationship between climate and the amount of body hair.”20

As flattering as it may be to think of ourselves as adaptable, flexible creatures, we are not so plastic as argued by these overplayed “explanations,” which ignore man’s inherited or intrinsic attributes. Magazines and journals are lousy with adaptive explanations for everything from stubby legs to long noses. But may I ask: Why do women have a wider pelvis than men? Will you explain that by natural selection? No, it is simply inherent design. Even Lucy’s modernized pelvis cannot be chalked up to evolutionary pressure: Why is the human pelvic opening larger than that of the apes? The ready answer is that it was an adaptive change allowing for the larger-headed human infant to pass through. Yet the head size of Lucy’s people (australopiths) was no larger than an ape’s.

“Adapative” is so broadly used, it loses all meaning: “Intelligence is obviously adaptive,”21 but consider this—apes are smarter than monkeys but are going extinct while monkeys abound. Go figure.

ON THEIR HIND LEGS

There is no end to these contrived explanations: the teeth of first man Ardi (Asu) were short and blunt (humanlike) because the males “no longer needed to bare sharp fangs to scare off competing males” (and get the gals). Instead, they now won the gals by going far off “on their hind legs,”22 bringing back enticing gifts of food! This fishy line of reasoning is part of the vaunted but improbable savanna hypothesis, which argues that human bipedalism evolved simply from the need to walk increased distances across open territory (the dry savanna of Africa). Part of evolution’s presumptive logic and circular reasoning is the habit of explaining things by a need for them.

Climate change, it is asserted, having transformed Ardi’s Africa into open grassland (savanna), made standing upright a great advantage. Ardi thus became bipedal due to walking and food gathering, or perhaps by looking over tall grasses (constant surveillance against predators favored a standing posture), even though: (1) George Gaylord Simpson himself, the acclaimed comparative zoologist and champion of neo-Darwinism, says bipedality is an adaptation to desert, (2) “bipedalism is not really the best way of getting around in a hostile world,”23 (3) there are disadvantages to bipedalism: a monkey can outrun a human being, (4) baboons get on quite well on four legs in the savanna, indeed making faster escape from the toothed predators of that open environment, and (5) finally, upright bipedal posture may go deeper into primate history: the “common ancestor” of both chimps and humans could have been already bipedal, say some theorists. Nevertheless, it is held that humans got bipedal because of the need to carry things in their hands, or perhaps the need to expose less body surface to the sun. The final pitch is high drama: If our ancestors had remained in the forest and not gone on to savanna life, “we would not be here.”24

But who can believe such fables? That these conjectural scenarios led to major structural change is as whimsical as the Lamarckian principle of acquired characteristics being inherited.

Down from the trees, but not out of the woods: Another problem with all this is that Ardi (Asu) probably lived in woodlands, not open plains, at least according to paleobiologist Tim White. For example, Laetoli (Au) was already bipedal while living in Tanzania’s woodlands, not in savanna. Earliest man was a creature of the woodlands, a closed habitat (only later was his mixed descendant, Au, associated with open country). Soil research says the African savanna itself is not even 3 myr, while Ardi has been dated to 4.4 myr.

The philosophy of evolution stands or falls on the platform of natural selection, which postulates that the changes that define species come about through adaptations to the rigors of life. Hence, survival of the fittest, meaning: those best equipped to adjust to a given environment have an edge in survival and a better chance of reproducing after their own kind. Which is fine, theoretically; but evolution then boils down to a negative meaning, really, which is to say: The important changes in the gene pool will be the elimination of characteristics too feeble or ill suited to meet the demands of life. Natural selection, in other words, selects or filters out the weaker strains. But how does it account for new and better genes? Or for brand-new species? Where does the improved stuff come from?

Being a conservative force, natural selection merely prevents the survival of extremes, removing defective organisms in order to keep the status quo. Its work is to weed out deleterious genetic information, not innovative or creative at all, but pruning. It “chooses” from among a pool of variations—nothing actually new is introduced.

So where do novel genes come from (like H. sapiens’ prominent chin, high forehead, bigger brain)? They presumably turn up by mutations, which of course are incidental, haphazard events. Despite this randomity, genetic mutations are royally crowned as the grand force behind the development of humankind—the human brain! Could chance events have fashioned the cerebral cortex in all its complexity, with more than ten billion cells all carefully coordinated? Darwinists say yes; let’s have a look at their reasoning.

THE TOOL-FOOD-BRAIN CONNECTION

Recent workers, such as Meave Leakey (along with Richard himself and anthropologist Robert Martin), tell us that the brain requires a great deal of high-energy food; therefore, early man’s increasingly creative use of tools (for hunting, hence for meat getting) must have been the impetus for brain growth. The energy provided now by hunted meat supposedly fueled the development of a bigger brain: “Meat and bone marrow gave them the extra energy to grow larger brains.”25 Thus did technological advances and hunting allegedly give us not only more gracile bodies but also better brains.

But have we got the cart before the horse here? This is the same sort of spurious causality argued by Louis Leakey in 1960—that tool use sped up the evolution of the Zinj hominids (he later abandoned this fruitless argument). Indeed, Ernst Mayr pointed out that freeing the arms to use tools could not have been the main reason for the increase of brain size, for even apes use tools. Nevertheless, a minute later, Mayr said Au’s need for “ingenuity” (against predators) is the deciding factor that “created a powerful selection pressure for an increase in brain size”!26

No hominid species shows any trend to increased brain size during its existence.

STEPHEN JAY GOULD, “EVOLUTION: EXPLOSION NOT ASCENT,” NEW YORK TIMES

But let me stop and ask: Could tools really have refined our anatomy? Or is it a fact that those people who used tools in the first place were already AMH, the earliest Ihin-blooded races? I agree with George Frederick Wright who contended that the more modern behaviors are the results of greater mental capacity “rather than their cause. It is not the use of tools that has produced his mental capacity. It is his mental capacity which has invented tools.”27

It is hard to believe such patent chimeras (tools made the man), given that Hooton, so long ago, cautioned that no “gorilla will ever invent a knife or fork; and if he did invent them and use them, I doubt if his jaws would shrink. . . . Handling things does not necessarily produce thought, nor do tools make the brain grow.” Why do today’s workers ignore his warning against “facile mechanistic interpretations of . . . evolutionary changes . . . evolving an entirely new species out of a new habit.”28 Carl Sagan, for example, had man’s knowledge of tools “even-tually propelling such feeble and almost defenseless primates into domination of the planet Earth.”29 Tool use, as we saw, is also claimed as a cause of bipedalism (according to C. Loring Brace and many others), even though bipedal Au. afarensis (Lucy) had no tools; tool use actually came “long after bipedalism.”30

HOT FOOD AND BIG BRAINS

What stimulated human evolution from our apelike ancestors? Cooking, says Harvard University biological anthropologist Richard Wrangham, a former student of Jane Goodall. That way, more nutrition reached our energy-hungry cerebrums, allowing them to “evolve” to their present capacity. This is how H. erectus got such dramatically larger brains than Au (a jump of 400 cc): their use of fire for cooking.31

In Darwin’s own time, the Archbishop of Dublin saw Darwin’s theory as “Lamarck’s cooked up afresh . . . [especially] the conversion of the unaided savage into the civilized man.”32 Even though modern theorists have thoroughly discredited the old Lamarckian doctrine of habitual behavior influencing genes, here it is again, driving the theory that Neanderthal’s ruggedness (large incisors, forward position of jaws, long face, supraorbital torus, and low cranium) developed out of his habitual use of teeth as tool; and also that fire and cooking eventually reduced the massive jaws of early Pleistocene man. I think we made more sense one century ago, following Arthur Keith’s “full examination of all the facts [which] has compelled me to reject such Lamarckian explanations.”33 Mayr, for one, doesn’t much care for Wrangham’s assumptions: “Almost everything in this scenario is controversial . . . [especially] the date when fire was tamed.”34

Figure 9.2. Sir Arthur Keith.

Nonetheless Wrangham seems to have good company: Milford Wolpoff found an “evolutionary” trend of cheek teeth getting smaller as AMHs began “evolving,” the progressive change supposedly reflecting improvements in food preparation. According to Brace, excellent tools reduce the size of molars and the bulky shape of face and jaw.35 Brace then used these “changes” to explain why Australia’s northern Aborigines, with greater “technological elaborations,” like seed grinders and nets, have smaller teeth than southern Aborigines, who lack this technology. I’ll stick with Hooton, who, concerning this supposed dental reduction in African groups, inferred that “this size diminution may have been caused by hybridization [e.a.] of the large-brained type with . . . pygmies.”36

All these primordial cooks are a misdirection: “There is no positive evidence . . . the Pithecanthropines even knew fire.”37 At the famous Peking site, the hearths (the ash deposits in these caves) could have just as well belonged to a more advanced type (like the Ihuan hordes) who hunted H. erectus! After all, Weidenreich showed that Peking man coexisted with AMHs. Or Peking Man’s remains “may have been introduced by carnivores. . . . The ash layers are not hearths and may not even be ash. . . . Animal bones in the deposit are not evidence of hominid diet.”38 Lumps of burned clay could simply represent tree stumps consumed by brush fires; “baked” clays and ashes could be natural objects of volcanic origin, prairie fires, or lightning (“geofacts” versus artifacts).

Druks did not cook their food, though they ate all manner of flesh and fish and creeping things; probably their main meat was carrion. According to a recent study, they snacked more extensively on termites than on meat. Even late in the game (around 6 kya), the ground people (in Egypt) were still eating fish, worms, bugs, and roots. Druks may have been carnivorous (H. erectus sites suggest baboon kills), but not necessarily hunters; heck, even Au ate baboon brains.

Actually, current theory needs H. erectus to possess fire, allowing him to have made the great migration out of Africa; fire would have been essential for their widespread dispersal into colder regions. If H. erectus colonized Europe and Asia, how else could he have survived during the glacial winters there? Yet we cannot use logic alone to reconstruct history, especially presumptive logic. Although it has become fashionable to announce unambiguous evidence for controlled fires by H. erectus, it is by no means certain that they could actually start fires. Even if Peking Man did have fire, he may not have known how to start one: the depth of the hearth layers indicates he did not permit his fires to go out, which is the custom of even historical tribes who cannot start a fire. Today, African pygmies on the Epilu River do not know how to make fire; nor did the Andamanese and Tasmanians of the nineteenth century.

Regular fire use began in Neanderthal times39; only in later Neanderthal deposits are there signs that they ate cooked grains (bits found in their teeth). Neither were the Ihuans full-fledged carnivores until around 22 kya, while actual fire making in Africa is probably no older than 20 kyr.40 And in America, it was not until 18 kya, that their angel mentors taught the Ongwees how to cook flesh and fish to make them more palatable. And this was the first cooked food since the days of the flood.41 Similarly did the Greeks credit an unseen host, the god Phos, with their ability to control and use fire, just as the “advanced beings” (ABs) gave fire to man. It was also in this manner that the South American Tukano Indians learned the art of fire from their god Abe Mango, while the Kuikuru of Brazil say they had fire brought to them by the god Kanassa; likewise did the Aztecs have a fire god—Xiuhtecuhtli.

MAN THE HUNTER

Just as fire and cooking may in fact be more recent than current theory credits, man the hunter is not old enough to figure in the evolution of our species. Was H. habilis a “competent hunter,” thus setting humanness in motion? Anthropologists claim that H. habilis brought back meat to be butchered and shared. However, follow-up digs at Africa’s Olduvai Gorge uncovered additional H. habilis skeletons, which revealed that this “mighty hunter” was tiny (under four feet tall). Here, on the open savanna bristling with lions and saber-toothed tigers, H. habilis was likely spending a lot more time cowering in the trees. Cut marks superimposed over tooth marks indicate they were probably scavenging scraps of carcasses. Nor were the Neanderthals particularly organized hunters, but rather opportunistic ones, killing prey on an encounter basis—“rotten hunters” according to University of Chicago’s Richard Klein. Even the “great mammoth hunters,” as critics point out, may not have been hunters at all but marginal scavengers, at least until the late Mousterian. The much later people of Klasies River, and all other South African hominids for that matter, were not efficient hunters until 50 kya,42 long past the age of H. habilis.

Sherwood Washburn, who led the dubious school of causality claiming that culture shapes physiognomy (rather than vice versa), argued that the “success of this adaptation” (hunting) dominated the course of evolution, resulting in “our intellect . . . and social life.”43 This way of thinking includes, of course, the notion that our bigger brains were developed on savanna land, as the forests, with its many fruits, retreated. With the switch to hunting and meat eating, hominids required “even greater cooperation and longer hunts.” Or so they say. A great deal is made of this cooperation. Did early man hunt cooperatively? So what if he did; wolves, lions, hyenas, orcas, hawks, goatfish, and apes hunt cooperatively. Even one-celled animals form collectives; such grouping “appears very low down in the scale of development indeed.”44

In three short sentences, the clincher word evolutionary is used five times by an anthropologist pitching the importance of hunting and eating meat: “The incorporation of meat-eating in the diet seems to me to have been an evolutionary change of enormous importance which opened up a vast new evolutionary field. [It] ranks in evolutionary importance with the origin of mammals . . . it introduced a new dimension and a new evolutionary mechanism into the evolutionary picture.”45

But just the opposite, really: it was the vegetarian Ihins who were the real thrust of humanity; the sacred little people ate no flesh food, teaching that all life was sacred: “Neither killed they man nor beast nor birds nor creeping thing that breathed the breath of life.”46 Among their descendants, for example, the Atlantes people of North Africa, as mentioned by Herodotus, “ate no living creature.”

TALKATIVE CHIMPS

Analysts would have us believe that humans improved their communication skills by hunting together; that we got our enhanced gray matter because we “had to obtain foods [large animals] that were even harder to find,” and therefore we cooperated and communicated more fully. Thus is it argued that “diet accounts for the different paths taken by humans and the apes.” This is how “humans became talkative chimps.”47 Believable? Even clear thinkers like Ashley Montagu and Ernst Mayr have turned causality toward agenda: “Speech . . . exerted an enormous selection pressure on an enlargement of the brain.”48 To get around the circularity of these arguments, they call it a “feedback loop”: brain develops language and language develops brain!

We are told that because greater resourcefulness was needed (in drying Africa), bigger brains were selected to deal with the problems, the challenges. This “need” thing blunders into the supposition that human speech came along as a response to “adaptive pressures” and “demands on communication”49 (in the movement away from the free-and-easy forest). Speech now arose because it was needed in the hunt; perhaps the threat of animal predators on Au led to such useful adaptations as “the evolution of increased vocalizations.”50 The need to share vital information on food sources is what “stimulated the development of fluent speech.”51 And these are the flimsy fictitious factoids taught today in institutions of higher learning.

Today’s interpreters, then, are saying that the Great Leap Forward was caused by our capacity for speech: “development in language . . . propelled early modern humans to cultural dominance.”52 This inverted causality is an affront to both reason and scholarship. Recent researchers have gone so far as to suggest the bizarre idea that “early human language evolved as a way to effectively groom several people at the same time. . . . Having a larger vocal repertoire allows you to have a more complex social set-up. . . . Language arose as a form of group grooming.”53 (The idea, of course, is based on reciprocal grooming as observed among apes). Once the group got larger, say these theorists, vocal exchanges replaced the bonding created by one-on-one grooming. And this moon-shine passes muster in today’s prestigious journals. Seeing that population levels increased at sites of early mods, Erik Trinkaus, for example, suggests that “larger groups inevitably demand [e.a., there’s that “need”] more social interactions, which goads the brain into greater activity . . . creat[ing] pressure to increase the sophistication of language.”54

Darwin believed that the “social feelings” were innate: “Most of our qualities are innate.”*115 Language, I would argue, is innate, too, hardwired into our brains, like thought. “The premise that cognition evolves [e.a.] . . . is not only unproven—there is actually no evidence for it.”†116 According to Noam Chomsky, the great MIT linguist and Nobel Prize winner, language was not acquired through natural selection, nor did it evolve. To Chomsky, “deep grammar” is built into the human brain only—not the ape brain. Indeed, Stephen J. Gould endorsed this “universal grammar.” Language is simply one aspect of big brain, not a cause of it, as argued by evolutionary scientist Christopher Wills: “the force that accelerated our brain’s growth . . . [includes] language, signs, collective memories.”‡117 But cognition cannot be “explained” by evolution; language, thought, and consciousness are givens—part of the intrinsic inheritance of the human being; we come thus equipped, hence, the hyperbolic myths of Krishna and Noah, who spoke as soon as they were born. The givens, irreducible and fundamental, do not need to be explained. They are self-evident, like the Buddha’s “suchness of reality”: “Ours not to reason why.”

If you’ve had enough of the “experts’” wizardry, let’s see how speech really fits in the human picture.

THE MECHANICS OF SPEECH

When man first became widely diffused, he was not a speaking animal.

CHARLES DARWIN, THE DESCENT OF MAN

Darwin was right: Only fully upright man is a speaking man: the vertical column must be erect, not only to support his large brain, but to permit the mechanism of speech. It is for this reason that the talking birds (starling, raven, parrot) can utter words, for their larynx (voice-box) is vertical. Asu and Au, however, had the larynx rather high in the throat, limiting the range of sounds; you need a larynx low in the throat for humanlike articulation.

And man [Asu] was dumb, like other animals; without speech and xwithout understanding.

OAHSPE, BOOK OF INSPIRATION 7:2–3

Lucy, an Au, was not much of a speaker, judging from the air sacs attached to her hyoid bone. Neither is articulate speech possible without a fairly flexible neck. This flexion at the cranial base is missing in early man; the bottom of their skulls, the basicarnia, is flat, limiting production of vowels and consonants. The Au palate and pharynx, in addition, are unsuited for articulation. Early hominids in general had shorter pharynges; one needs a longer pharynx to modulate the vibrations produced in the larynx.

But the modern vocal tract is not why humans can speak, it’s how. The spoken word did not make us human, for speech is part of humanity, inseparable from brain power, an aspect of brain power.

Let us pause and ask if language, as claimed, was the cause of improved culture and complex social organization. Can we agree with today’s experts who reckon that man’s command of language triggered the cultural explosion of the Upper Paleolithic? We cannot, judging from the Kebara find in Palestine: a Neanderthal that came after AMHs in the Near East and that had an anatomically modern larynx*118—yet Neanderthals never did make that Great Leap Forward.

The Max Planck people made big news with their “astonishing find” of Neanderthaloid El Sidron (Spain) specimens who share with mods a version of the gene called FOXP2, which contributes to language ability: “they possessed some of the same vocalizing hardware as modern humans.”55 Neanderthals also had a modern hyoid bone, enlarged thoracic spinal cord, and a Broca’s area (even H. habilis had Broca’s area, a feature of the AMH brain).

True to the record, in Hopi myth, the First People could not talk. The Maya Quiches also say the antediluvian race was without intelligence or language, for when Gucumatz and Tepeu first attempted to fashion human beings, the result was a dumb creature who could not speak or worship their creator. Neither did H. P. Blavatsky’s third root race have spoken language: they lived, like the ground people, in pits dug into the earth. Even after the flood, the ground people had little speech (ca 21 kya).*119 As late as the nineteenth century, the Sri Lankan Nittevo, now extinct, had speech reportedly like the twittering of birds, while other eighteenth-century travelers mentioned Madagascan “manimals” who apparently did not speak any language. Even in our own day we hear reports of throwbacks, such as the cryptid Jacko, caught in British Columbia in 1884 (see chapter 12), who spoke in a half bark, half growl.

But have our paleoanthropological experts got it backward? Thinking that speech ability led to larger brains and modern behavior?: “Articulate speech . . . opened up whole new vistas . . . [and stimulated] brain development”56—the idea probably inspired by Darwin’s strange logic: that speech, in time, helped perfect the mind.

Having found mod features in the vocal tract of hominids who possessed neither the culture nor the intellect*120 to go with it, theorists had to save the day, somehow. Thus it is that Tattersal and Schwartz posit the vocal tract as a feature prepared in advance—its downward flexion traceable all the way back to some members of H. heidelbergensis, 500 kya. However, no symbolic or linguistic or cognitive behavior is evident before 50 kya. This 450-kyr gap is then explained by something called exaptation (or preadaptation)—a desperate gambit, inventing something that lay “dormant” in the genome until needed for some new purpose.

Such features, as the argument goes, were present in the ancestor, but they were doing something else initially, say breathing, and later were put to a different purpose, say eating or speaking. Thus may a population be “adapted in advance . . . a good example of a human exaptation is speech,” the necessary structures having been in place “well before” language actually arose.57 The modern vocal tract “must have been acquired in another context, possibly . . . a respiratory one. . . . Our ancestors possessed an essentially modern vocal tract a very long time before they used it for linguistic purposes.”58 Nonsense—it appears only because of genes inherited from early AMHs. Exaptation has become a convenient catchall solution, or as cosmologist Sir Fred Hoyle ventured, a “rubbish bag for all evolution’s awkward odds and ends. . . . Talking about pre-adaptation is simply a way of avoiding the issue.”59

This pseudo-explanation called “exaptation” now crops up in zoological evolution: In the case of saurians “evolving” into birds for example, the morphology of proto-wings is a “crucial flight feature [that] evolved long before birds took wing. It’s an example of . . . exaptation: borrowing an old body part for a new job. . . . Bird flight was made possible by a whole string of such exaptations stretching across millions of years, long before flight itself arose.”*121 Rubbish. Feathers, allegedly, had evolved long before they were used for flight—which only came later as a by-product of dinosaur arm-flapping and gliding to balance themselves as they made fast turns. Eventually the flapping evolved into the repetitive strokes of wings. Yeah, right; just like the giraffe got a long neck from repetitive stretching for the golden apple. This exaptation is craft, not science.

MUTATION: DUMB LUCK

Structural and chemical complexity reduces the chance of evolution by mutation to near zero. . . . The chance mutation of genes causing a series of concerted, appropriate behaviors would be more than a miracle.

BALAZS HORNYANSZKY AND ISTVAN TASI, NATURE’S I.Q.

The fortuitous character of evolution by mutation is certainly a coincidence of the highest order. Mutations, after all, are errors that occur during cell division. They are copy mistakes made by DNA, sometimes producing striking deformities. To get “good” evolution, you need a thousand favorable copying “errors” all in the proper order and in the right direction. How likely is that?

The mutation argument for evolution was famously debunked by the great cosmologist Fred Hoyle, who quipped that a living organism emerging by a series of chance events is about as likely as a tornado in a junkyard assembling a Boeing 747 from the materials therein. What a singular stroke of luck that out of the chaos of blind forces emerged this prince of beings—man!

By what trick of mesmerism have we fallen under the spell of such intellectual sorcery—making haphazard mutations the cause of order and design? Most new mutations actually become extinct because they only happen once; besides, some of these “mutations” may actually be recessive traits coming out!

The laws of probability rule out advantageous random changes on any but the smallest, most insignificant scale. A finely graded series, all stages heading in the same direction, is not only implausible in the highest degree but also absent in the fossil record. Evolution teaches the improbable; that the great diversity of life is due to atypical, aimless deviations from a norm—the vanishingly small chance of accidental design features (itself an oxymoron, for design means plan)—that still, somehow, add up to superb system and order! This blind random process, “a giant lottery,” in Michael Denton’s words “is one of the most daring claims in the history of science.”60 Fred Hoyle, for his part, could not believe that chance (or even any earthbound theory) could produce genes capable of writing the plays of Shakespeare.

Figure 9.3. Ray Palmer—“Planets hold to orbits, day follows night; the seasons progress in fixed order. Everything that lives and grows does so by a process that is consistent and not haphazard.” Ray Palmer was editor of Amazing Stories, Fate, Mystic, and Search magazines, as well as publisher of Amherst Press and the 1960 edition of Oahspe.

The belief in randomity, the faith in it, as against system and purpose, is very much a piece of philosophy, not really science. It is my understanding that the deeper a society (like our own) falls into anomie (a form of rootless alienation), the quicker it embraces unhinged notions of randomity and purposelessness, utterly losing sight of the universe with all its grand order and design. Even the evidence is against it, as geneticist Ronald A. Fisher put it: For mutations to afford evolution, one must postulate mutation rates immensely greater than those that are known to occur. Or as Gould saw it: “mutations have a small chance of being incorporated into a population.”61

Genes are a powerful stabilizing mechanism whose main function is to prevent new forms evolving.

FRED HOYLE AND N. C. WICKRAMASINGHE, EVOLUTION FROM SPACE

When lab manipulations aim for eyelessness in fruit flies (Drosophila), it does indeed produce a strain of sightless flies. But given enough generations, some force seems to step in and once again the offspring have eyes. Called reversion, this response betrays genetics as the machinery of stability—not change, not innovation, not evolution. And “to observe a mutation” in the laboratory, thought French biologist and Nobel Prize winner Jacques L. Monod, “is a very far cry from observing actual evolution.”62 Yet so many evolutionary claims depend on experimental breeding programs with insects and little animals. Can we extrapolate from fruit flies to human beings? Do you really think that bombarding fruit flies with X-rays is a good way to find out about the history of man’s evolution? Even mutated fruit flies are still fruit flies—eyes or no eyes—and have not speciated to some other critter.

Neither are large mutations—the stuff of “rapid evolution”—likely to be an improvement; chances are, a big jump, genetically, will end in death. Most macromutations, as they are called, are lethal, for any mutation big enough to cause an important change would, by the same token, be fatally disruptive. “Mutation is a pathological process which has little or nothing to do with evolution.”63 Change a gene too much, “and it will be unable to continue its existing functions.”64 Mutants are usually short lived and leave no progeny.

Only tiny changes (micromutations) have a chance. Darwin called them “infinitesimally small” modifications. Indeed, Dixon thought whatever the modifications in man’s development, they were “far more likely to have affected the superficial rather than the actual structural portions of the body.”65

With evolution pinned on random mutations, it is most damaging to find that mutations are overwhelmingly negative and admittedly rare; natural selection actually operates against them. Are human beings the exception to the rule? “Many geneticists express doubt that genes have evolved. . . . Genetic variations are more likely to be harmful than helpful.”66 Not a few biologists will tell you that mutations are pathological and can have nothing to do with evolution.

Perhaps most telling is the observation concerning novel traits in flowers: “What looked . . . like mutants were actually hybrids.”67

INDIVISIBLE COMPLEXITY

Francis Crick, Nobel prize winner, proved that DNA was far too complex to have evolved by random chance. The accidental synthesis of DNA molecules and its associated enzymes would be a coincidence beyond belief. Ask any biochemist. The unfathomable interworking of DNA demands an explanation of order and pattern, not chaos and happenstance.

The unsolvable problem is this: How could so many complex parts evolve piecemeal yet work together toward a coherent whole? The theory of mutations is empirically and even logically unacceptable. We’re talking about thousands of small changes—all happening coincidentally and randomly, yet evolving together in tandem? Please. This is a step in reasoning no thinking person should be asked to take. Minor changes over millions of years, all in exactly the right direction, producing mutually beneficial behaviors? Tell that to the judge.

Partial, incomplete, changes (so-called transitional forms) would be of questionable value to an organism, indeed a hindrance. “The piecemeal evolution of birds’ lungs from reptiles’ lungs,” for example, “seems virtually impossible. The survival of [such] intermediates . . . is totally inconceivable.”68 Biochemist Michael Behe finds no living thing that can be “put together piecemeal” and provides many examples of how the complex machinery of life could not have “come into existence . . . in step-by-step fashion.”69

Correlation of parts (as the matter is classically phrased) implies an all-or-nothing situation, and it is this indivisible web of interrelationship that defies evolutionism and its cozy, safe-sounding “step-by-step” changes. Something more systematic must be involved.

Correlation of parts in the house mouse, for example, entails coat-color genes that have some effect on body size; they are interrelated. In fruit flies, induced eye color mutations actually changed the shape of the sex organs. “Almost every gene in higher organisms has been found to effect more than one organ system, a multiple effect,”70 and these effects are species specific—which means, of course, it doesn’t “evolve” and turn into any other kind of animal, any other species.

It is a question of orchestration, of interdependence.

Each change, taken in isolation, would be harmful, and work against survival. You cannot have mutation A occurring alone, preserve it by natural selection, and then wait a few thousand or million years until mutation B joins it, and so on, to C and D. Each mutation occurring alone would be wiped out before it could be combined with the others. They are all interdependent. The doctrine that their coming together was due to a series of blind coincidences is an affront not only to commonsense, but to the basic principles of scientific explanation.

ARTHUR KOESTLER, THE GHOST IN THE MACHINE

Georges Cuvier, an opponent of evolution, regarded organs as so intimately coordinated within the matrix of life that no one part can be fitted to perform a function without affecting other parts. In comparative anatomy, each major group of animals is seen to have its own peculiar correlation of parts—every structure functionally related to others and too well coordinated to survive major change through evolution. All the elements of change must be simultaneously present, and how incredible that would have been, a coincidence beyond belief, coordinating, in synch, all the accidental factors involved.

Figure 9.4. Georges Cuvier. Zoologist, comparative anatomist, paleontologist, once known as the Aristotle of biology, the French scientist was also a statesman and public figure. Cuvier was opposed to the concept of evolution, even before Darwin came on the scene.

Irreducible complexity, said Behe, involves a “meshwork of interacting components . . . matched parts that block Darwinian-style evolution.” Change one link in the chain, and the system is seriously endangered. Gradual evolution, Behe goes on to argue, cannot by any stretch of the imagination account for the origin of: the immune system, metabolism, blood clotting, antigens, photosynthesis, DNA replication, vision, cellular transport, protein synthesis, metabolic pathways—all of which participate in an integrated, irreducible matrix. Darwin’s tiny steps, analyzed biochemically, are a sham, “wildly unlikely.”71 Nor could the symbiotic relationships we find throughout nature have developed gradually, by “incipient stages” or trial and error.

AN INTRICATE WEB

As book review editor of a research journal, I was once asked to review Balazs Hornyanszky and Istvan Tasi’s Nature’s I.Q.: Extraordinary Animal Behavior That Defies Evolution. Outside the English-speaking world, French, German, Swedish, Russian, and East European biologists and ethologists are not so sold on Darwinism. This colorful book by two Hungarians, Hornyanszky and Tasi, advances the view that species do not and never did evolve from one another, citing “countless instances of complex . . . mechanisms whose origin the theory of evolution is helpless to explain. It seems much more reasonable to conclude that a being possessing higher intelligence equipped all species with the organs, knowledge and abilities they need.”72

Nature’s I.Q. was translated from the original Hungarian to English in the “Year of Darwin” (the 2009 bicentennial of Darwin’s birth), a time when audiences were focusing attention on the undying controversy of Evolution versus Intelligent Design. From the notorious 1925 Scopes “Monkey Trial” in Tennessee (where the two views locked horns) to ongoing curriculum wars in Texas and other states, this great debate just won’t quit, and with the publication of Hornyanszky and Tasi’s delightful animal study, it becomes crystal clear why the great debate has continued without stint for 150-plus years. Gradual evolution of traits and behaviors does not hold up to scrutiny; rather, they appear to be quite simply innate, givens.

Never letting the facts get in the way, the Darwinists ask us to believe that a series of chance events (mutations) have resulted in the highly intricate mechanisms enjoyed by members of the animal kingdom. Thus does science continue to ignore the inherent order in things. How is it that the house of evolution, built upon the shaky, unscientific principle of blind chance, luck of the draw, has endured? How can the honest man say that one anomaly or mutation—freak, really—after the other has created the incomparable architecture of each and every species?

The matchless efficiency in nature that these Hungarian scientists regale us with, its interactive attunement, harmony, and wonder—in weaverbirds, night moths, scorpion fish, horned frog, mallee fowl, praying mantis, crested grebes, humpback whales, pelicans, starlings, sea turtles, cicadas, and dozens more—is all consigned (by godless science) to random transmutations within each species; the grand theory of evolution thus teaching us and our children that nature’s precision and majesty are nothing more than a collection of fortunate accidents, a series of chance events, a chain of randomity bordering on a miracle—no, make that “more than a miracle” (according to Hornyanszky and Tasi).

Blind chance, to these authors, is perfectly laughable in the face of the keenly interconnected faculties found everywhere in the animal kingdom. It is “out of the question” that step-by-step change could result in the carefully arranged and coordinated equipment possessed by living creatures, simply because the behavior is “adaptive” only in its final form; there’d be no survival advantage at all in “incipient stages.” Rather than natural selection or survival of the fittest, it is an intelligent designer, say these authors, who supplied each family of creatures with their life-enhancing characteristics.

Take the South American four-eyed frog whose fake eyes on its rump help to scare off aggressors. To these scientists, it is almost a joke that the posterior eyes appeared suddenly from a mutation, in exactly the right position and with the right markings; not to mention that the frog knows what mask it has on its derriere and behaves accordingly—turns its back on the attacker and lifts its rump-mask menacingly. These ethologists say point blank that the theory of evolution “is on the level of fairy tales.” Indeed, “the sudden appearance of such complex biological systems, as if by magic, is completely impossible.”

Flower and fertilizing insect fit each other like hand in glove. Has this sort of symbiosis “evolved” over and over again in thousands of species by blind chance? No, according to paleontologist Robert Broom and geneticist Richard Goldschmidt, the latter showing that complex mammalian structures could not have been produced by the selection and accumulation of small mutations, which can only account for minor changes within the species boundary. Large-scale mutations would produce “hopelessly maladapted monsters.”

If you make Chance your creator, you are likely to get nothing but monstrosities as your creatures; you cannot make an alarm clock by whirling bits of scrap iron in a closed box.

JACQUES BARZUN, DARWIN, MARX, WAGNER

SPEAKING OF MONSTERS

What science calls mutations (or Loren Eiseley calls “genetically strange variants”) may be nothing more than unfortunate hybrids, the result of unwise mating, in which case, we ask: Have humanoid monsters arisen from mutations or simply from mixing? Some esotericists have interpreted the Sons of God/Daughters of Men myth of biblical fame as a parable of mismatched genetic codes—the merger of the holy watchers with Earth men, their offspring “not quite human.” The antediluvian patriarch Enoch, reasons one writer, knew about this mating between angels and earthlings, which resulted supposedly in the birth of mutants, “hybrid beings of all kinds, contaminated, depraved, a terrifying mixture of intelligence and beast.”73 Another extraterrestrial interpreter supposes that similar unnatural couplings produced hybrid beings, half human and half animal, that “nearly brought about the disappearance of the human race.”74

But leaving extraterrestrials out of our search for monsters, let us consider Carl Sagan’s suggestion that “occasional viable crosses between humans and chimpanzees may be possible.”75 Perhaps this is where our monsters lie. The school of theosophy, accounting in its own way for legendary monsters, posited that the fifth subrace of Lemurians, being stupid things, interbred with beasts. Some of the acclaimed (and controversial) Ica stones of Peru depict such bestiality. Indeed, today’s paleontologists are not above suggesting that the ancestors of chimps and humans may have interbred, about 6 mya.76 Even in today’s world, we occasionally hear of cases such as Siberian village children born from sexual matings between humans and savage humanoids like Yeti.77

In 2001, Michael Brunet and his team made a strange fossil discovery in the Sahara Desert of Chad: six individuals of the race of Toumai. Officially named Sahelanthropus tchadensis, they were dated 6 to 7 myr (the time of the supposed split of anthropoid apes and hominids). This Toumai, put forward as the “common ancestor” of man and ape, possessed a mosaic of human and nonhuman traits. He had an apelike cranium (only 370 cc), round eye sockets, very prominent brow, and a short muzzle; yet he had a flat, vertical, humanlike face*122 and small teeth. Thought to be an upright, walking creature, Toumai was only three feet three inches tall. Prehuman? They found that the angle at which his spinal cord connects to the brain was like humans and quite different than the chimpanzee’s much more acute angle. Sahelanthropus also had a pattern of tooth wear like humans.

Yet, rather than accepting Toumai as a common ancestor, might we ask if he was a hybrid of Asu and ape? Stephen Jones, editor of Cambridge Encyclopedia of Human Evolution, on the very first page (xi), mentions the possibility of early crosses between man and ape, for we are “extremely close cousins” (sharing 98 percent DNA). There are also “rumors of test-tube crosses between men and chimps.”78

The earliest traditions of Western civilization remembered a time when Earth brought forth monsters, be it legends of the north, with monsters in the region of the Gobi Desert; or India’s memory of a world “polluted with monsters” (at the time of Krishna’s birth); or the Babylonian creation epic, describing Earth as peopled with gods, men, and monsters; or the Chaldean goddess who sired a crop of monsters; or the classical Greek legend of the grotesque Cyclops.*123

Turning to Hebrew tradition, we learn of a time when the purity of the race was imperiled by degrading sexual customs: “There was a time . . . when both men and women had sexual intercourse with animals, from which resulted the birth of monsters.”79 The Bible (Lev. XVIII) warns: “Thou shalt not lie with any beast to defile thyself therewith. . . . It is confusion.” Hebrew legend, moreover, recalls that in the antediluvian period, the tribe of Seth was of noble blood, but then the children of his son Enos(h) became idol worshippers, those who “strayed,” their sins changing the “countenances of men. . . . No longer in the likeness and image of god, they resembled centaurs and apes.”80 Is this a remembrance of the four-footed Yaks (see below) or Pan the satyr (of the early Greeks) who was the most debased child of these miscegenations? Myths depicting men transformed to animals are fairy tales, of course, but their ineluctable kernel of truth lies in the retrobreeding of Adam’s sons. “I showed him that every living creature brought forth its own kind; but he understood not and he dwelt with beasts, falling lower than all the rest.”81 (The time frame for this Oahspe quote matches the advent of the patriarch Enosh and “apeish” men, ca 65 kya.)

Cain, Adam’s son, was not above retrobreeding with the lower races: “The Druks (Cain) went away in the wilderness, and dwelt with the Asuans. . . . And because the Druks had not obeyed the Lord, but dwelt with the Asuans, there was a half-breed race born on the earth, called Yaks . . . and they burrowed in the ground like beasts of the forest. And the Yaks did not walk wholly upright, but also went on all fours [giving us eventually the goatlike satyrs of the Greeks]. And the arms of the Yaks were long, and their backs were stooped and curved.”82

Prehistoric drawings on pottery found in southern Peru depict a queer manimal with bent back and long thin arms, rather like images in the strange catacombs hidden in the cliffs of Easter Island, these frescoes representing a humanoid with a catlike head; the curved form has a rounded back and long skinny arms. Who was this prehistoric monster, this unknown race? Were they Yaks?

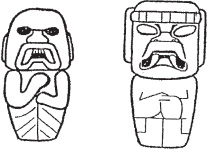

Figuer 9.5. Greek Pan, a metaphor, really, of degenerated man.

Figure 9.6. Yak. It is possible that creatures like Zinj, Denisova, and Dmanisi were Yaks, a race produced both before and after the flood, thanks to retrobreeding. Illustration from Oahspe.

The first wave of Yaks, before the flood, resulted from the admixture of Asu (animal-man, with zero percentage of Ihin blood) and Druk/H. erectus (hybrid man, with 50 percent Ihin blood). The Yak therefore had only 25 percent fully human genes. I believe the name Yak has been retained in the languages of the world. It is curious that the long-haired, hump-shouldered, wild ox of Central Asia, domesticated as beasts of burden, are called yaks—just as the subhuman Yaks of old were made into servants,83 to build, sow, and reap for the higher races. In fact a Japanese word for servants is yakko.

The name Yak persists in India, where the yakshas are spirits of the wilderness, and Hiran-yak-ashas are legendary giants. In Malaysia, Yak Jalang is the name of one ancestor. In Japan, the Gilyaks, like the Neanderthals, had a cult of bear sacrifices; these people were somewhat hirsute like the Ainu. In Northern Europe are the Votyak people. In Borneo are the headhunting Dyaks.

In Siberia are the dolichocephalic Ostyaks (proto-Australoid), the Koryaks of Kamchatka, and the Yakuts hunters. The Siberian Yucaghiri is phonetically Yakaghiri. It is, after all, from Siberia that we hear reports of humanoids like Yeti (almost a Yak type). In America are the Guayaki tribe of Paraguay, the Yakina Indians, and the Yaqui (Yaki) Indians of New Mexico. Among some California tribes, Sin-yak-sau was the first woman. In addition, the Yakama forest in the Cascades abounds in legends of animalistic Stick Indians; while the Yak name also seems to be recalled in places like Yakima (Washington), Yakutat Bay (Alaska), Tuk-to-yak-tuk (Canada), and the Eyak languages of the Pacific Northwest.

Oahspe makes mention of a great number of monstrosities betwixt man and beast before the time of Apollo. No, man did not come from the beast so much as he became one by these unruly mixings: thus it is said by theologians that “the sons of Adam erred,” filling the world with cannibals and manimals, apes, and centaurs. Such off-spring were without judgment and of little sense, hardly knowing their own species. And they mingled together, relatives as well as others.

Figure 9.7. The Yakuts are a Turko-Tatar tribe near the Bering Strait. Yakuzia is the name of a region in northeast Siberia.

And idiocy and disease were their general fate, though they were large and immensely strong. Because of their marvelous power and brawn, we find them glorified in legend and icon, which we may interpret as a remembrance of the extraordinary strength in the bloodline of the ground people, the race of Cain, the burrowers (Druks). They were so strong, their grip could break a horse’s leg, like the incredibly strong arms of Nittevo, Jacko, didi, and Orang Pendek (see chapter 12). Even the Ihuans, being the offspring of the Ihins and the ground people, inherited this corporeal greatness; they fought in popular arena games, unarmed, catching lions and tigers and “with their naked hands, choking them to death.”84

But back breeding brought disease and deformity. According to tradition, Mexico’s Cholula pyramid was built by gigantic men of deformed stature, the legend matched perhaps by the Old World cyclops and titans, also great builders, but bestial in both act and appearance, having “union with beasts.” Huge, misshapen, and violent also were the Fomorians of Celtic myth.

The book of Genesis says “all flesh had corrupted his way upon the earth,” much as Oahspe recounts: “They bring forth in deformity on the earth,”85 for mortals descended rapidly in breed and blood when the Ihins mingled with the large Druks,86 their offspring afflicted with catarrh, ulcers, lung, and joint diseases (i.e., deformed). Earth before Apollo was overrun with monstrosities, men and women looking like a dog that is tired, with deformed spines.*124

Lesions have been found on Neanderthal skeletons as well as African specimens, which show abcesses, rheumatism, and joint disease. Paleontologists say the average life span of Au in Swartkrans, South Africa, was seventeen years! Even the lifespan of the Neanderthals was no more than forty years, while half of them died by age twenty. Numerous specimens had crippling ailments, many with rickets and syphilis. Smithsonian workers found many deformed bones and syphilitic lesions on ancient skulls in Patagonia.

In the tenth century, when the Scandinavian Vikings reached northeastern America, near Rhode Island, they found there a race “totally distinct from the Red Man . . . whom they designated Skrellingr [sic], or ‘chips,’ so small and misshapen were they.”87 It was “the same race as in Labrador . . . [whom] they contemptuously call Skralinger . . . and describe as numerous and short of stature.”88 In Mexico as well, the deformed little Puuc were hunchbacked like the Skralinger. Such crooked men in the Americas have been confirmed archaeologically: Owen Lovejoy excavated skeletons with “strange physical deformities . . . [and] many unusual bones.”89 And in Africa as late as the nineteenth century, de Quatrefages reported on deformed pygmies south of Abyssinia.

Asia also has its misshapen figures. In Tibetan legend, the Han-Dropa tribe, of unknown breed, were supposedly so weird that their Chinese neighbors tried to exterminate them. Puny and fragile, four feet tall, they possessed disproportionately large heads. Their eyes were large with pale blue irises. A similar whispery race was known to live in North America, south of Cherokee country, a tribe of little people called Tsundige’wi, with very queer-shaped bodies, living in nests scooped in the sand. The little fellows were so weak, said the Cherokee, that they could not fight at all, and were in constant terror from the wild geese and other birds that came to make war upon them.

Figure 9.8. Puuc depicted in Mexico’s Loltun Caverns. Illustration by Jose Bouvier.

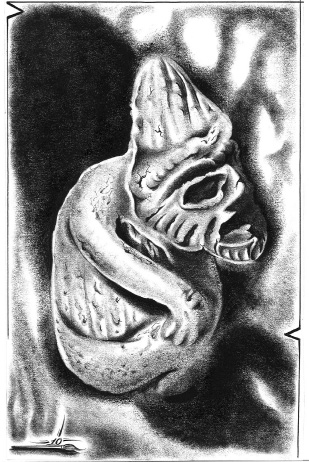

Figure 9.9. “Misshapen gods” are represented in Olmec art by “jaguar-men” and other monstrosities depicting all types and stages between man and beast.

Figure 9.10. A large-headed African figurine.

Yet not one of these “hopelessly maladapted” races was the product of natural selection. The vagaries of hybridization—not mutation—once peopled Earth with surprising spawn, such as are recalled in our own “enlightened” age only in the fables and fairy tales of children.