THE STAR SISTERS: HELEN AND LUCILLE WESTERN

Men drooled when Helen Western, with her glossy brunette hair and large, lustrous eyes, “dazzling in their brilliancy,” appeared on stage.1

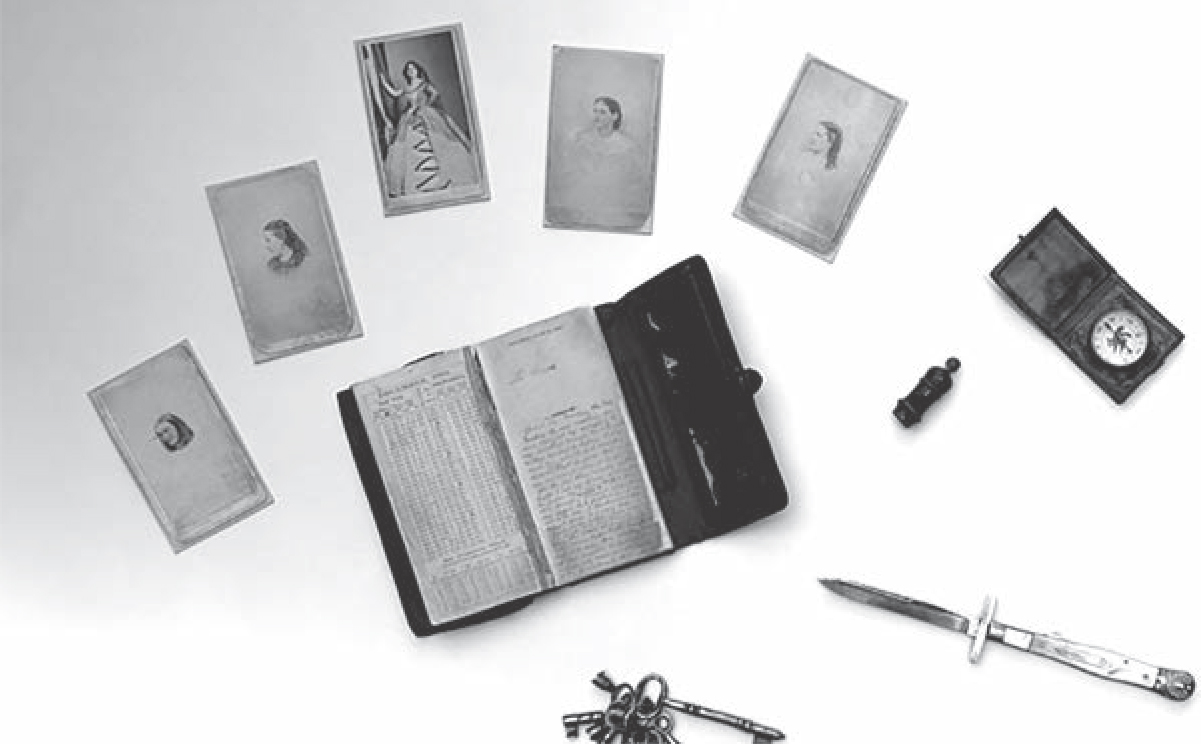

John Wilkes Booth knew many beautiful women—many of them intimately—in his life. When John died he had five photographs in his pocket. Four of them were of actresses. One of those actresses was Helen Western.

When Helen and her older sister Pauline Lucille came to Richmond in April 1860, they were still known as the “Star Sisters.” Both girls were born in New Orleans. Like many performers of that era, their parents were both entertainers.2 And like many youngsters from theatrical families, Helen and Lucille (she dropped her first name at an early age) went on stage almost as soon as they could walk. By 1852, they were touring the New England circuit from Boston to Bangor, Maine, with their mother in William B. English’s “Dramatic Company” (by then their father had died). Lucille acted the part of a boy, and Helen was the sentimental heroine. By 1856, they were already being called “the old Boston favorites.” In 1857, Bill English married their mother and became his wife’s and Helen’s and Lucille’s manager.3

Photos and other items found in John Wilkes Booth’s pocket at the time of his death. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Bill English was not oblivious to the stares his tall, dark, graceful, adolescent step-daughters were getting from men in the audience. He had been in the business long enough to know that sex sold. A few years earlier he had leased the National Theatre in Boston to put on an act so risqué for its time, the theatre manager’s son beat him with a stick for lowering the “respectability” of his father’s theatre.4

English became manager of Boston’s National Theatre the same year he married their mother and cast the “Star Sisters,” English’s new name for Helen and Lucille, in a racy melodrama, The Three Fast Men or The Female Robinson Crusoes of America. The play, featuring them both as men in barely concealing disguises that showed off “the graces of their figures,” opened to rave reviews on March 9, 1857.5 “The most attractive piece ever written,” commented the New York Clipper. “It is the quintessence of comedy, the par excellence of ingenuity. Although occupying three full hours, it is the only piece on record that entertains an audience so long and so merrily.”6 The Boston Herald was similarly enchanted: “There has not been such an excitement to witness a play within the memory of the oldest inhabitant.”7

English had not anticipated how big a hit he had. Two days after the play opened, the Boston Herald reported The Three Fast Men had attracted the largest houses in the National Theatre’s history. “It is estimated that there were three thousand persons there on Monday evening; every part of the house being packed full. . . . Miss Lucille personates seven distinct characters. Miss Helen also has quite a number of parts in her hands, and she sings the sweep song capitally.”8

The storyline involved three young women trying to lure their men, who have gone astray, back to the straight and narrow by disguising themselves as men and behaving in ways that show the errant males their error. Helen and Lucille appeared as sailors, organ grinders, drunkards, gamblers, chimney sweeps, pawnbrokers, rowdies, or some other dissolute characters. Sometimes they appeared in eight different roles.9 The play ended with a minstrel set in which the male actors sat around in a semi-circle strumming a banjo while Helen and Lucille danced jigs and sang.10 At one point the mood turned pensive while the musicians played “A Maiden’s Prayer.” The song was the “hit” tune of the play and became a favorite parlor piano piece of the Civil War Era.11 At the end of the play, the three fast men married the three devoted women, and everyone lived happily ever after.

Two weeks into the play’s run, the Boston Herald reported “the house is regularly besieged every evening. Last night the lobbies were crowded to excess.”12 The following week, the Boston Herald reported “hundreds unable to get seats.”13

Lucille initially garnered most of the accolades. Four days into the show’s run, the “charming Lucille received bounteous applause.” When she appeared in her sixth “protean” character, some women sitting in a private box threw a bouquet of flowers with a small purse attached onto the stage. Inside was fifty dollars in gold. “Miss Lucille,” punned the Boston Herald, “is winning golden opinions from everybody, and she deserves them.”14

Helen received her share of attention too. Nearing the end of the play’s run, the Boston Herald printed a poem to Helen by an anonymous admirer. Her eyes, he wrote, were like “beams of sun,” and her cheeks were “like roses in bloom.” Her ringlets were as “black as the curtains of night and glossier than the raven in flight” and floated “sunnily down to a bosom of snow.”15

The Three Fast Men played for eighty-seven consecutive nights in Boston, “unprecedented in the annals of theatricals” until then.16 After another unprecedented three weeks each in Philadelphia and New York, the “Star Sisters” were back at Boston’s National Theatre.17 “Lucille,” the Boston Herald commented, was “admirable.” Helen was “prepossessing . . . [she] has a bewitching face and great powers of pleasing.”18 Six months later The Three Fast Men played at the National Theatre yet again.19 Fans were encouraged to stop by Page’s store windows to see Cutting & Turner’s “elegant photographs of Lucille and Helen, in their protean character.”20

William Dean Howells, novelist, playwright, and editor of the Atlantic, attributed The Three Fast Men’s success to what he considered its underlying theme of morality.21 Less high-minded men in the audience came to leer at Helen and Lucille in revealing clothes. The working class “b’hoys” at New York’s seedy Old Broadway Theater didn’t scream and whistle at the girls because they were feeling virtuous.22

Despite The Three Fast Men’s popularity among eastern audiences, theatre critics in the west criticized the girls’ scanty costumes and the play’s lewdness.23 The New Orleans Times-Picayune did not mince words: “Whatever is low in fun, disgusting in allusion, vulgar in taste, and impure in morals, may be found in the ‘Three Fast Men.’ Any decent woman would blush to be seen at its representations, and any decent man should be ashamed to countenance it by his presence.” In Cincinnati, the play was “suppressed by order of the police.” Far from discouraging audiences, the notoriety lured them into the theatres. “It is all very well to say the wretched burlesque they appear in is of a bad and immoral tendency,” said another reviewer, but nevertheless, “people go to see the curls and the ankles of two plum and pretty girls—and those who do so, with no intention but that of unreflective enjoyment, will not be disappointed.”24

Confusing Weston and Western, the Cincinnati Daily Gazette claimed Helen and Lucille’s moral failings were not surprising since they were sisters of Lizzie Weston Davenport, the adulteress at the center of a public scandal in New York.25 Helen and Lucille sued the Cincinnati Daily Gazette for $10,000 for libel. “This is quite an unique case,” the Pittsburgh Daily Post editorialized, “one of the first we remember wherein persons have brought suit for being furnished with false relatives.”26 Fans in Boston were riled at the insult to their favorite actresses.27

After appearances in Detroit, Cincinnati, Louisville, Chicago, and other major cities in the west, the “Misses Lucille and Helen Western, the young ladies whose rosy cheeks, gaiety of style, etc., made such an excitement among the ‘b’hoys,’ some months ago,” were back at the Bowery Theatre in February 1859.28

Three months later, Helen and Lucille leased the National Theatre on their own and cast themselves in “the New Popular Play, Sickles; or, The Washington Tragedy.” The Detroit Free Press reported the play was “a very close and correct dramatization from the facts, and offers with it a good moral in the pure and Puritanical city of Boston.”29 The “facts” involved adultery and murder. In February 1859, New York Congressman (later Major General) Daniel E. Sickles shot D.C. District Attorney Philip Barton Key (son of Francis Scott Key, author of “The Star-Spangled Banner”) in cold blood outside Sickles’s house in Lafayette Square for having an affair with Sickles’s wife, Teresa, for more than a year.30 In a landmark case, in which Sickles was represented by future Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, Sickles was exonerated on grounds of “temporary insanity.” It was the first time the insanity defense was successfully used in the United States.31

Sickles was no show stopper. After a short stage run, Helen and Lucille dropped the play and resumed their stage careers. For the rest of the year they were the headliners in theatres across the United States and Montreal, Canada.32

Bored with performing with some semblance of modesty, Helen and Lucille began dressing even more provocatively in The Three Fast Men and their quips and banter had more sexual innuendo. The New York Clipper commented Lucille and Helen were overdoing it: “We receive every day awful accounts of their too natural style of acting.” The New York Clipper advised them to “dial it back.”33

Helen Western in a French spy costume. Courtesy of New York Public Library, Billy Rose Collection.

The only ones complaining they were overdoing it were the theatre critics. St. Louis’s theatre critic scowled Helen and Lucille were “poor actresses, and only to be tolerated before Bowery audiences,” but he had to admit St. Louis’s audiences were jamming the theatre every night.34 A critic in Wheeling, Virginia, was just as disapproving of the play’s “immoral tendency” and just as unpersuasive in discouraging people not to attend.35

Meanwhile, sixteen-year-old Lucille had met twenty-nine-year-old James Harrison Mead in St. Louis and was canoodling with the “small and spare framed” ruddy-haired actor.36 After they married in September 1859, Mead gave up his own acting career and became Lucille’s business manager. It was the beginning of the end for the “Star Sisters.” Helen and Lucille stayed together for another two years, but Lucille’s marriage started a fissure that eventually cracked their act apart. For one thing, the sisters no longer shared the same room. For another, despite being married, Lucille still had a roving eye and was not above flirting with men interested in Helen.

Helen and Lucille’s next engagement was at the Marshall Theatre in Richmond.37 John had been at the Marshall for two years by then. He performed with Helen and Lucille every night except Sundays during their three-week engagement. Like every other male in the cast and in the audience, he was likely smitten with the two sisters, especially Helen, who was coming into her own and no longer simply Lucille’s younger sidekick. John was handsome and charismatic, but there is no record of either sister spending time offstage with him. A year later, however, the “Star Sisters” would be at each other’s throats over which one of them John preferred to spend his nights with.