Thirteen

How to Outguess Ponzi Schemes

From the 1970s through 2008, three longtime employees of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities—David Kugel, Annette Bongiorno, and Joann Crupi—did the paperwork. “I worked together with them to create the false trades and make them appear on investment advisor client statements and confirmations,” Kugel told a federal judge. The trades were invented to correspond to a return on investment that Madoff himself decreed for each of his clients. It was the Bizarro World version of money management. Instead of calculating the return from the trades, Kugel and company made up trades to match the return.

This isn’t the way Bernie Madoff started, assuming he can be believed. “I… was successful at the start but lost my way after a while and refused to admit that I failed.” Soon afterward Madoff began inventing numbers.

The money management business is founded on trust. How does an investor know whether the numbers on the statements are for real? The standard advice is to be a judge of character and deal only with those managers you’re sure you can trust. That’s exactly what Madoff’s clients did. A line on the company’s website once ran, “Clients know that Bernard Madoff has a personal interest in maintaining the unblemished record of value, fair-dealing, and high ethical standards that has always been the firm’s hallmark.”

Another rule of thumb is never invest in anything you don’t understand. Though the sentiment is laudable, it’s unrealistic in today’s complex financial universe. Some people don’t truly “understand” money market accounts or index funds. Should they keep their money in a mattress? In any case, someone investing with a miracle-working manager should not expect a complete explanation of how he makes the money. That’s the secret sauce.

Madoff’s investors believed he had achieved annual returns of something like 10 percent a year with low volatility, and had done so over an otherwise volatile decade. Despite what you may have heard, this wasn’t too good to be true. Other money managers have racked up better records.

Jim Simons started his Medallion Fund a couple of years before Madoff did. Since 1988, Medallion’s return has averaged 45 percent a year. Simons is a mathematician who hires only mathematicians and scientists and sequesters them in a compound on the north shore of Long Island, where they invent top secret trading algorithms. The fund has done especially well when the general market plummets. Medallion’s best year was 2000, with a return of 99 percent. In 2008 Medallion was up 80 percent. “When everyone is running around like a chicken with its head cut off,” said Simons, “that’s pretty good for us.”

Simons doesn’t offer details, and neither will anyone else who aims for comparable returns. Successful hedge funds must constantly invent new strategies as old ones are reverse engineered by competitors and become played out. Were the methods disclosed to investors, the secrets would leak faster.

The black-box nature of the business is well illustrated by a mortifying incident. Stony Brook University asked Simons, formerly of its math faculty, to recommend a good manager for its endowment fund. Simons introduced them to… Bernie Madoff. The university invested with Madoff and lost $5.4 million. Some might have looked at Madoff’s returns and figured they were too good to be true. Simons knew they weren’t.

The rule should perhaps be reworded: Never invest more than you can afford to lose in something no outsider understands. Many of Madoff’s victims violated that rule, putting practically all their assets with him. One of the more suspicious things about Madoff was how transparent he was. He claimed to use a split-strike conversion strategy. That jargon is meaningful to professionals (though no one could figure out how Madoff made it pay the way he claimed). At least some clients got statements that ostensibly listed every trade. That should have made it possible to figure out Madoff’s system, assuming he had one.

At least one person tried. In 1991 hedge fund manager Ed Thorp—also known as the inventor of blackjack card counting—was asked for his opinion on a company’s investments. Thorp saw that the returns for the account with Madoff were fantastic. Curious, Thorp asked Madoff for more detail on his trades. He got it and quickly determined that something was fishy. On April 16, 1991, Madoff had supposedly bought 123 call options for Procter & Gamble on behalf of the client. Thorp found that a mere twenty Procter & Gamble calls had been traded that day. In other cases, too, Madoff claimed to have bought or sold more of a security on a given day than was traded in total. Thorp advised his client to pull its money out.

Retaining a trusted expert is the best way to check out a money manager. Thorp’s reputation must have helped him get the trade-by-trade information he needed.

Mark Nigrini argues that the numbers themselves could have pointed to Madoff’s fraud or similar ones. Madoff had at least two sets of made-up numbers, the monthly returns (evidently set by Madoff himself) and the fake trades (invented by his minions). There were three people making up trades, and they made the prices fit the historic record. Given that the fictitious sale prices were constrained by the day’s trading range and the prescribed returns, it’s hard to say what their digit distributions should look like. The monthly returns, however, apparently came straight from the mind of Bernie Madoff. Returns are the one thing that any manager, no matter how secretive, must disclose to investors.

At least one set of Madoff returns has been disclosed, those for the feeder fund Fairfield Sentry. Founded in 1990 by Walter Noel and Jeffrey Tucker, Fairfield Sentry gave Madoff a global reach, pitching Madoff’s “algorithmic technology” to wealthy institutions worldwide (minimum investment $100,000). The Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, JPMorgan Chase, Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria (Spain), Nomura Holdings (Japan), and numerous Swiss banks were among those that bought a piece of Madoff’s wizardry via Fairfield Sentry.

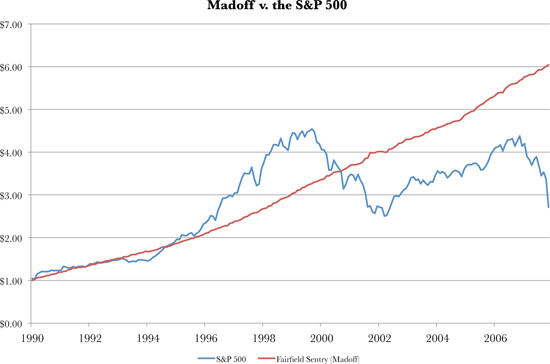

In its first month, December 1990, Fairfield Sentry claimed a return of 2.77 percent. It reported monthly returns through October 2008, when it had a small loss of 0.06 percent. By that point its reported assets were over $7 billion, accounting for more than a tenth of the assets under Madoff’s management. A dollar invested in Fairfield Sentry in December 1990 would have turned into $6.04 by October 2008—had you only been able to collect it. That averages out to a 10.6 percent annual return.

More eyebrow-raising was how steady the claimed returns were. The chart shows the value of a dollar invested in Fairfield Sentry against a dollar invested in the S&P 500 index. Fairfield Sentry was not only steadier than a stock index but steadier than US Treasury bonds.

Madoff knew all about volatility. But when he came to invent fake numbers, he fell back on the not-so-rational instincts we all share. He apparently felt a need to keep monthly returns close to the average he was pitching. Only once (January and February 2003) did he deliver two negative returns in a row.

You might look at the chart and say that returns can’t be that consistent. Then you wouldn’t have put your money with Madoff, and that would have been the right call. Fairfield Sentry’s investors, some of them the world’s most astute bankers, were hardly naïve. They understood that everyone who runs a hedge fund is claiming to walk on water, one way or another. They assumed that Madoff’s preternaturally low volatility was a feature of his winning algorithm—whatever it was.

Things started to go sour in August 2008. JPMorgan Chase redeemed a quarter of a billion dollars from Fairfield Sentry. The official story was that they’d become “concerned about lack of transparency.” Meanwhile Madoff and Fairfield Sentry were working on a new fund. It would use more leverage to achieve returns of 16 percent. Fairfield Sentry reportedly warned its investors that anyone who dared to withdraw money, and anyone so foolish as to not invest in the new fund, would be punished in the severest way possible, by being blacklisted from investing in any future Madoff funds.

Madoff was arrested on December 11, 2008.

Fairfield Sentry’s monthly returns were given to the hundredth of a percentage point. That means there are only two or three significant digits. Rounding discards information (or in this case, it means Madoff didn’t bother to invent the information in the first place). Despite that, it’s easy to see that Madoff’s monthly return numbers were unusual.

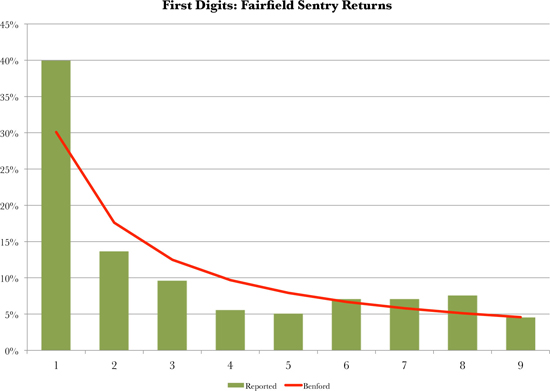

Let’s start with first digits, the test in which Benford’s law comes most into play. Nigrini recommends omitting negative values (or analyzing them separately), as the incentive is to minimize a loss. I’ve also omitted a few cases where there were fewer than two significant digits. That leaves 190 values, all two- or three-digit positive numbers. The bars show the actual first-digit tallies, and the line shows the ideal Benford distribution.

Forty percent of the returns start with 1. That’s well beyond the 30 percent predicted by Benford’s law. The digits 2 through 5 are underrepresented, and there’s an excess of 7s and 8s. These differences are statistically meaningful.

Madoff was claiming returns of about 11 percent a year. That means the monthly returns would tend to be close to 1 percent. These returns were rock steady, never straying too far from the mean. Take all that at face value, and you’d expect a disproportionate number of months with returns in the range of 0.70 to 1.99 percent. That would create an excess of first digits of 7, 8, 9, and 1, and a deficit of the other digits.

That’s what we do see, with one exception. The first digit 9 occurs in just about the Benford proportion. This contrasts with the greater-than-Benford occurrence of the digits around it.

A likely explanation is manipulation. Like everybody else, Madoff knew that a return of 1.00+ percent feels a lot bigger than one of, say, 0.99 percent. So he avoided 9s. Monthly returns that otherwise might have started with 9 were bumped up to 1.00+ percent. It’s difficult to think of an alternative explanation even if you buy Madoff’s claim of fantastically low volatility. Why else would steady returns skip over values starting with 9?

Now let’s look at the last two digits of the monthly returns. The chart of last two digits, from 00 to 99, shows a ragged picket fence with some slats missing. Several digit pairs are far more common than the others. The chart’s most remarkable feature is the spike for 86. Those are the last two digits for eight of Fairfield Sentry’s monthly returns. There are also three pairs that occur 6 times: 14, 26, and 36.

This is consistent with the unconscious repetition of invented numbers. This idea becomes more compelling when you look at which digit pairs were repeated: 86, 14, 26, and 36. All but one end in 6.

In fact, there are nine last pairs ending in 6, and they occur 33 times total. That is twice what you’d expect.

The Fairfield Sentry returns are routine by tests of doubled last digits and descending pairs. With 190 numbers, you’d expect about 19 to end in doubled last digits. In fact, there are 24, more than expected. (Remember, fabricators usually shy away from doubled pairs.) The only thing slightly suspicious is that 55, which many fabricators avoid, does not occur.

There are nine descending pairs (10, 21, 32…) and they occur 17 times, almost exactly what would be expected.

In short, the Fairfield Sentry returns seem to have been manipulated to yield more months topping 1 percent. The figures are also suspicious for the profusion of returns ending in 6 and 86. Two other criteria of invented numbers were not present. Overall, these findings don’t prove that the returns were made up, but they are far from reassuring.

As a potential investor your first concern would have been deciding whether you were comfortable enough to hand over your money—that, rather than proving beyond doubt that Madoff was a fraud. Were you to find yourself in a similar situation, the most reasonable response would be to ask for more detailed return figures, with more significant figures. This request would pose no threat to the confidentiality of the trading algorithms. Should the manager say no, you’d ask yourself whether you want to invest with someone who won’t even tell investors exact returns.

In the aftermath of the scandal, a CNBC journalist obtained Madoff’s golf scores from the Golf Handicap and Information Network. Madoff self-reported twenty games played between 1998 and 2000 at Palm Beach Country Club, Atlantic Golf Club, and Fresh Meadow Country Club. The scores were as weirdly consistent as his investment returns, and three of the twenty scores were 86.

Recap: How to Outguess Ponzi Schemes

• Financial schemers may fabricate and manipulate data. Be suspicious when too many numbers just top a psychologically significant threshold.

• A last-two-digits test can help detect fraudulent managers who unconsciously favor certain digit pairs.