Twenty One

How to Outguess the Future

Predicting the future is big business. It was estimated that companies worldwide spent close to $400 billion in 2012 on forecasters of all kinds. Most of that involves old-fashioned human expertise, though increasingly the prediction business is touting data analytics. Either way, some skepticism is in order.

“Each year the prediction industry showers us with $200 billion in (mostly erroneous) information,” complained William A. Sherden back in 1998. “The forecasting track records for all types of experts are universally poor, whether we consider scientifically oriented professionals such as economists, demographers, meteorologists and seismologists, or psychic and astrological forecasters whose names are household words.” Sherden was himself a business consultant.

In a now-notorious study, psychologist Philip Tetlock followed some 284 political and economic experts over two decades, ending in 2003, to see how accurate they were. He found that the experts did no better than nonexperts.

We reach the point of diminishing marginal predictive returns for knowledge disconcertingly quickly. In this age of academic hyperspecialization, there is no reason for supposing that contributors to top journals—distinguished political scientists, area study specialists, economists, and so on—are any better than journalists or attentive readers of the New York Times in “reading” emerging situations.… Experts in demand were more overconfident than their colleagues who eked out existences far from the limelight.

In 2011 Tetlock initiated a tournament, sponsored by the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Agency, in which thousands of experts compete to make accurate predictions in their fields of expertise. It’s hoped that the tournament will reveal something about how intuitive predictions succeed—when they do succeed.

We are often asked to evaluate predictions about future events that may not be predictable at all. To avoid being suckered, it’s worth knowing a little about the art of making poor predictions look better than they are.

Faith Popcorn, futurist and CEO of the consulting firm BrainReserve, is famous for issuing annual lists of predictions (not unlike the psychics in the National Enquirer). A few examples:

• People will become so starved for human contact that “mechanized ‘hugging booths’ ” will take the place of payphones.

• There may be “a surge in popularity of 1950s slang.”

• Reality shows will stage American Idol–style auditions for “risky but life-saving organ transplants, skin grafts, and limb replacements.”

• Robots will walk dogs, drive buses, and serve fast food. Technology “will turn battlefield decisions over to robot troops.”

• “As the cost of genetic modification plummets, engineering services will… create pets from scratch and pepper your future companion’s DNA with your own.… These animals will be such an accurate reflection of your temperament that therapists will begin seeing pets as proxies for their patients.”

You may think this is funny, but the Fortune 500 isn’t laughing. BMW, McDonald’s, Procter & Gamble, American Airlines, and Target are among Popcorn’s clients. Like other successful forecasters, Popcorn understands that she’s partly in the entertainment business. Her wilder predictions keep her name in the news, the better to build a client list. Like psychics, business forecasters pretend to have a magical ability that is inexplicably channeled to the prediction of amusing trivia. It’s hard to see who would profit from advance word of the hugging booth meme (least of all any poor soul who tried to invest in them). The magic is in thinking that the prolific forecaster can predict anything—and will, if the client keeps her on retainer. Asks Popcorn’s website, “If you knew everything about tomorrow, what would you do differently today?”

The core expertise of business forecasters is in convincing clients that their circumscribed powers constitute miracles. That’s what mentalists do, and it’s not as easy as they make it look.

I recently saw a prediction effect by magician Dave Cox. An attractive young woman from the audience was brought onstage. Cox gave her some large prop cards that he said were an aid to focusing her thoughts. He showed one card to the audience. It had the word ROMANCE printed on it.

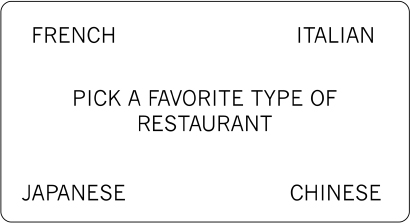

Cox had a small whiteboard. He wrote a prediction on it, out of audience view. He then asked the volunteer to imagine herself in a restaurant. What kind of restaurant would it be?

“Italian,” she answered. Cox turned the whiteboard around to show that he had written Italian.

I happened to be seated at the far left end of one of the closest rows to the stage. I was able to see Cox’s board quite plainly while he wrote—as most of the audience could not. There was no funny business. What I saw him write was what he showed to the audience.

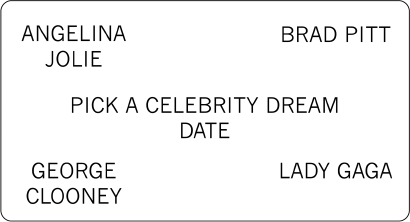

Cox wiped off the answer, wrote another prediction, and asked the volunteer to imagine that she was in the Italian restaurant with a celebrity dream date. Who would that be?

“Brad Pitt,” she said. Cox showed that he had written Brad Pitt.

Cox asked what she and Brad would order for dinner. “Pasta.” Cox asked what kind of pasta. “Spaghetti.” Cox showed the board: He had written chicken and was wrong this time.

The woman was asked to describe the pattern of the tablecloth in the restaurant and the type of beverage she would be drinking. Her answers were a red-and-white-checked tablecloth and red wine, both matching Cox’s written predictions.

Cox asked her to imagine what the bill would be. She said around $30. Cox’s prediction was $5.99. He flashed it to the audience and comically erased it by rubbing the whiteboard against his vest. He then displayed the erased board to the subject, saying the meal was free because Brad had picked up the check.

To the right of the stage was an easel announcing the performer. At the end of the act, Cox lifted up the show’s announcement to reveal a Photoshopped picture of Cox and Brad Pitt having dinner in an Italian restaurant with red-and-white-checked tablecloths. They were having chicken, and the bill was $5.99. The easel had been in plain view through the show, and I was almost close enough to touch it.

Cox does what successful business forecasters do, exploiting an illusion of representativeness and carefully managing memories. The volunteer was neither a plant nor a random audience member. At the outset Cox announced that he wanted “a young woman,” and that’s what he got. Few women (or men) who don’t meet that description will volunteer. Sexism and ageism that wouldn’t pass in the workplace are alive on the variety act stage.

The volunteer, in her early twenties, came onstage and was shown some cards. The audience assumed that the card that Cox showed (saying ROMANCE) was typical of the cards they didn’t see. Wrong. Some of the other cards were different, offering a multiple choice of answers.

These cards cued the volunteer with possible answers for the choices she would be given. Most people are a little tongue-tied when onstage and the center of attention. They will gladly choose one of the four canned responses. But the audience, unaware of the cards, will leave the theater wondering “What if she’d said ‘Korean barbecue food truck’?”

Another card cues the celebrity. The audience supposed the woman was choosing from the whole starry universe of celebrities. But prompted with the right four choices, most “young women” will choose Brad Pitt.

Not all the answers were cued. After the volunteer chose an Italian restaurant, Cox asked about the tablecloth and type of beverage, predicting the most likely answers (red-and-white-checked, red wine). The questions might have been different had other restaurants been chosen. Two of Cox’s answers were wrong. This was probably the result of the volunteer’s testing Cox’s powers or forgetting a cue. Cox was prepared to get comic mileage out of his mistakes, and the goofs “proved” that he was not just making safe guesses.

The easel had multiple versions of the picture, one for each cued restaurant choice. They were gimmicked so that Cox could lift up his title card to reveal just the picture he needed. All the pictures had Brad Pitt. They differed in the type of restaurant and details like the tablecloth and beverage.

The techniques of business forecasters are founded on similar psychology. Faith Popcorn makes it her business to learn about new pop-culture trends before her clients do. She is able to point out various instances of hot new things—and then argue that they are poised to be much bigger. Both the strength and the weakness of most forecasts is that they predict the continuance of recent trends. Valid or not, such projections are easy for the client to buy into because they appeal to our shared belief in hot hands. What just was, will be.

The skillful forecaster is an expert in managing memories. Cox’s mind-reading act is absolutely dependent on those mysterious cards shown the volunteer. The cards are also the first thing the audience forgets. When an audience member recounts the act to someone two weeks later, the cards will be long forgotten. They don’t fit the mental narrative, as they don’t serve a purpose that the audience member understands.

Business forecasters know that it’s the recollection of what happened in a meeting that counts. That’s why they like to end on a PowerPoint slide summarizing their successes. (Cox did almost the same thing.) A slide show for a 2011 talk lists some of Popcorn’s correct predictions, including

1987: Told Kodak to prepare for a “Filmless Future.”

1989: Told Coke to Bottle Water.

2006: Told Pepsi to stop bottling water.

2012: Predicting the “SHE-change,” a decade of feminine energy fueled by money, power, and compassion.

The Kodak bit was good advice—though at this remove, you may be left wondering exactly how ahead of the curve it was for 1987. Mainly, what people remember is the slide’s unverifiable heading—“95% accuracy predicting the future”—and Popcorn’s unforgettable name. She was born Faith Plotkin.

Recap: How to Outguess the Future

• Research argues that business and political forecasters are not much more accurate than educated nonexperts. Successful forecasters use mentalism-like techniques to enhance their credibility.

• Most forecasting invokes hot hand beliefs: Current trends will continue in the near future. This isn’t necessarily true, but forecasters know that their clients will believe it.

• Whatever happens last in a slideshow or meeting is most likely to be remembered. Successful forecasters are good at creating strong last impressions.