CHAPTER 7

POLITICAL SCANDALS

“Until this moment, Senator, I think I never really gauged your cruelty or your recklessness.”

—U.S. Army counsel Joseph Welch to Senator Joseph McCarthy, June 9, 1954, during the Army-McCarthy hearings

WASHINGTON BREEDS SCANDAL. Most every president and Congress has had scandals—whether brought on by policy decisions, like George Washington’s granting of most-favored-nation status to Great Britain, or by personal failings, like Richard Nixon’s paranoia or Bill Clinton’s libido. The Communist witch hunts of Senator Joe McCarthy during the Eisenhower era bathed the Capitol in an especially harsh light until the special counsel for the army, Joseph Welch, asked McCarthy if he had any “sense of decency.”

For President Donald Trump, scandal has been an almost daily occurrence, or so it seems at times: the firing of F.B.I. Director James Comey, the investigation into Russian meddling in the 2016 election, his former campaign manager Paul Manafort’s indictment on fraud charges, and the criminal investigation of Michael Cohen, his lawyer, who, among other things, arranged payments to women—including both a porn star and a Playboy model—to silence their accusations against Trump.

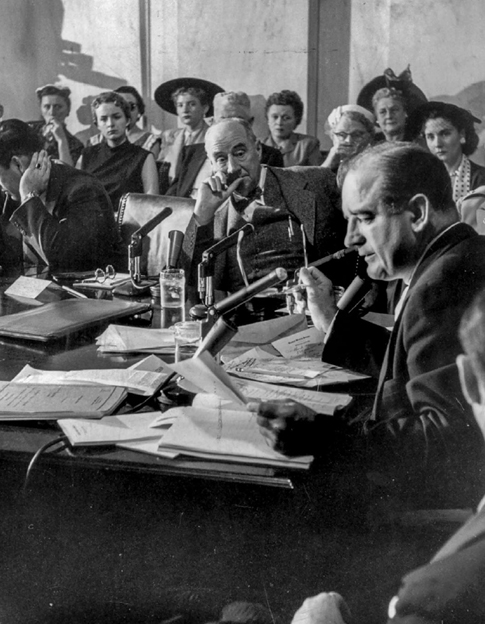

Senator Joseph McCarthy (right) and Joseph Welch, U.S. Army counsel (center) during the Army-McCarthy hearings in Washington, D.C., June 1954.

DEMANDS OIL REGULATION—LA FOLLETTE COMMITTEE SUGGESTS EIGHT IMMEDIATE REMEDIES

MARCH 5, 1923

Startling charge with respect to the oil industry in the United States are made in a report submitted to the Senate shortly before its adjournment today by Senator La Follette, Chairman of the Senate Committee on Manufactures, giving the results of its special investigation into the high cost of gasoline and other petroleum products.

The report charges that the oil industry today is under the complete control of the Standard companies, notwithstanding the decree of the United State Supreme Court in 1911 ordering the dissolution of the so-called Standard Oil Trust, and asserts that a careful examination of the evidence taken in the Senate investigation will show that in respect to the matter which “led to the outlawing of the Standard oil monopoly the same conditions exist as existed when the decree of the Supreme Court was entered.” The report further goes on to declare that “in some respects the industry as a whole, as well as the public, are more completely at the mercy of the Standard interest now than they were when the decree of dissolution was entered in 1911.”

“This point,” says the report, “cannot be too strongly emphasized for the reason that the intolerable conditions in the oil industry, which are established in the investigation, cannot be corrected while Standard Oil dominates the business as it does today.”

Warns of Dollar Gasoline

The report warns that if a “few great companies are permitted to manipulate prices for the next few years as they have since 1920,” the people of the country must be prepared before long to pay “at least $1 a gallon for gasoline.”

Besides the alleged Standard Oil control of the industry the La Follette report deals with the division of marketing territory between the Standard Oil companies, profits and prices, the effect of price changes, pipeline transportation, the situation in California, the so-called cracking process in the production of gasoline, alleged combinations among Standard companies, government concessions to oil companies, railway freight rates on oil, refinery operations, and gives detailed data relative to prices and stocks of crude and refined oil, gasoline and by-products, and concludes with the suggestion of eight suggested remedies.

That the report will be vigorously challenged by the oil industry was indicated tonight when Colonel Robert W. Stewart of Chicago, chairman of the board of directors of the Standard Oil Company of Indiana, before leaving Washington stated that in his opinion the La Follette report was “unjust” to his company and to the oil industry generally and “not based even on the testimony brought out during the hearings.”

Eight Remedies Are Suggested

Senator La Follette informed the Senate that it would be useless in the closing days of the session to present a bill—which there was no time to consider much less to pass—attempting to regulate the oil industry in any comprehensive manner, but he said the Senate committee suggests eight “immediate remedies,” adding that “their suggestions here made of certain remedies does not imply that other and more drastic ones may not later be found necessary.”

The “immediate” remedies suggested by the La Follette committee are:

1. A uniform system of bookkeeping in all oil companies doing an interstate business, which will show at any time in detail the costs and profits of the business so that reasonableness of the prices charged for any petroleum products can be ascertained on a cost basis.

2. A compulsory system of reports to a government bureau every month showing the operations of each oil company engaged in interstate business and particularly the quantities of crude oil and its products in storage or transportation.

3. That pipelines “must be made real common carriers,” with a view to divorcing the ownership of pipelines from the ownership of oil transported.

4. Changes in freight rates on petroleum products so as to permit the midcontinent refineries “once more to find a market” for their products through Michigan, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania and the New England states.

5. That exportation of petroleum and its products should be either prohibited or so regulated as not to permit the export from this country of those products for which there is pressing demand in this country, the view of the committee being that it is extreme folly to permit our resources of crude oil, gasoline and similar products to be drained out of this country.

6. That any attempt at price manipulation, such as the La Follette report alleges occurred during the past three years, should be made the basis of grand jury investigation in every state where such prices were made, and if existing laws are insufficient for this, then “such legislation should be speedily enacted.”

7. All parties to “implied” contracts or agreements, forbidden by the decree of the Supreme Court, should be cited by the court for contempt of the decree made when the dissolution of the Standard Oil trust was directed by the Court.

8. That the Department of Justice should immediately institute a rigid investigation into all claims for basic patents on pressure-still processes used in the production of gasoline.

Harry F. Sinclair of Mammoth Oil (left) and his counsel Martin W. Littleton during the Teapot Dome hearing, 1924. In 1922, Sinclair leased oil rights to a field near Teapot Rock in Wyoming directly from Interior Secretary Albert Fall, leading to the Teapot Dome Scandal.

Declares Change Is Imperative

“It must be obvious from the facts in this report,” Senator La Follette informed the Senate, “that the business cannot go on as at present organized and conducted. It is essential to the life of the industry and vital to the public also that neither the public nor the small independent producers and refiners shall not be left as at present to the mercy of a combination which advances or depresses prices as it pleases. Unless some means can be found to prevent the manipulation of prices by the large companies, and particularly the Standard group, it is as certain as any future event can be that gasoline prices in the near future will be so advanced as to put gasoline beyond the reach of the public generally as a motor fuel.”

Refers to Teapot Dome

“No greater concessions,” says the report, “have ever been bestowed upon oil companies in any land than that which the government of the United States has bestowed upon the oil companies in this country. It must be borne in mind that the vast oil-producing area in Wyoming now dominated by the Midwest Refining Company, owned by the Standard Oil of Indiana, was entered upon and wells drilled while the order of the president of Sept. 27, 1909, withdrawing the lands from location and settlement was well known. Not only were the lands so withdrawn, but in 1914 the Supreme Court decided that they had been validly withdrawn and that claims to location thereon arising since the president’s withdrawal order of 1909 were void.

WELCH ASSAILS MCCARTHY’S “CRUELTY” AND “RECKLESSNESS” IN ATTACK ON AIDE; SENATOR ON STAND, TELLS OF RED HUNT

By W. H. LAWRENCE, JUNE 10, 1954

The Army-McCarthy hearings reached a dramatic high point today in an angry, emotion-packed exchange between Senator Joseph R. McCarthy and Joseph N. Welch, special counsel for the Army.

Irritated by Mr. Welch’s persistent cross-examination of Roy M. Cohn, Senator McCarthy suddenly injected into the hearings a charge that one of Mr. Welch’s Boston law firm associates, Frederick G. Fisher Jr., had been a member of the National Lawyers Guild “long after it had been exposed as the legal arm of the Communist party.”

Mr. Welch, almost in tears from this unexpected attack, told the Wisconsin Republican that “until this moment, Senator, I think I never really gauged your cruelty or your recklessness.” He asked Senator McCarthy if any “sense of decency” remained in him.

“If there is a God in heaven, it will do neither you nor your cause any good.”

“If there is a God in heaven, it [the attack on Mr. Fisher] will do neither you nor your cause any good,” Mr. Welch declared.

Spectators Break into Applause

The crowded hearing room burst into applause for Mr. Welch as he abruptly broke off his conversation with Senator McCarthy. Mr. Welch refused to address any more questions to Mr. Cohn, counsel to the McCarthy subcommittee, and suggested to Karl E. Mundt, South Dakota Republican who is acting committee chairman, that he call another witness.

Senator McCarthy thereupon was called and took the stand on the thirtieth day of the hearing.

Senator McCarthy had interrupted Mr. Welch’s cross-examination of Mr. Cohn to denounce Mr. Fisher. He asserted, despite contradictions by Senator Mundt, that Mr. Welch had tried to get Mr. Fisher employed as “the assistant counsel for the committee” so he could be in Washington “looking over the secret and classified material.”

Senator Mundt said Mr. Welch never had recommended Mr. Fisher or anyone else for a subcommittee job. Mr. Welch explained that he had planned to have Mr. Fisher, a leader in the Young Republican League of Newton, Mass., as one of his own assistants in this case until Mr. Fisher told him that he had belonged to the National Lawyers Guild while at Harvard Law School “and for a period of months after.”

The violent, unforeseen character of Senator McCarthy’s attack seemed to upset Mr. Cohn, himself, whose facial expressions and grimaces caused Senator McCarthy to comment: “I know Mr. Cohn would rather not have me go into this.”

Senator Mundt has daily cautioned the audience to refrain from “audible expressions of approval or disapproval” of the proceedings on pain of being expelled from the hearing room. But he made no effort to control or admonish the crowd that applauded Mr. Welch’s retort to Senator McCarthy.

Disputes Obscure the Issues

The McCarthy-Welch exchange, and another hot battle between Senators McCarthy and Stuart Symington, Missouri Democrat, served to divert attention from the basic issues in this controversy. The army initially charged that Senator McCarthy and Mr. Cohn had sought by improper means to obtain preferential treatment for Pvt. G. David Schine, who until he was drafted, was an unpaid committee consultant.

Senator McCarthy and Mr. Cohn, in turn, have charged that the army held Private Schine as a “hostage” and tried to “blackmail” the committee out of investigating the army.

Other Highlights:

• Senator Symington specified that Senator McCarthy agree to explain whether, among other things, it had been proper for him to accept $10,000 from the Lustron Corporation for a pamphlet on housing, whether funds supplied to fight Communism were diverted to Senator McCarthy’s own use and whether he had violated state and federal tax laws and banking laws over a period of years.

• Charging that Senator Symington’s offer demonstrated “how low an alleged man can sink,” Senator McCarthy said he would give a firm commitment, but sign no letter, agreeing to testify before such a committee “if the Vice President or the Senate want to appoint a committee to investigate these smears.”

• Calling the exchanges divisionary and “mid-morning madness,” Senator Mundt tried to halt the personal feud between the two senators, but not until Senator McCarthy had denied that Senator Symington, while in private industry, had dealt with a Communist, one William Sentner, and paid him money to settle a strike.

The army and McCarthy sides are willing to end the hearings after Senator McCarthy and his subcommittee staff director, Frances P. Carr, have testified fully and been cross-examined. The Republican members and Senator McCarthy are seeking a specific date as a time limit, but Mr. Welch has thus far resisted that proposal. He has said he is willing instead to accept a stated number of turns in ten-minute cross-examination periods. The Democrats, on the other hand, have been fighting against an arbitrary time limit, and have insisted that other witnesses whose testimony may be material to the controversy may not be refused the right to appear.

Mr. Welch mixed humor with persistency in his cross-examination of Mr. Cohn early in the day. He made Senator McCarthy angry when he chided “these Communist hunters” for “sitting on a document for month after month” while they waited for committee hearings instead of telling Secretary Stevens about alleged Reds at Fort Monmouth.

He brought out that the altered F.B.I. report “purloined” from the army’s files had been given to Senator McCarthy last spring, but that not during March, April, May, June or July did Mr. Cohn or Senator McCarthy convey the information in it to Mr. Stevens. The crowd in the room roared with laughter as Mr. Welch added: “I think it is really dramatic to see how these Communist hunters will sit on this document when they could have brought it to the attention of Bob Stevens in twenty minutes, and they let month after month go by without going to the head and saying, ‘Sic ’em, Stevens.’”

“He knows it is ridiculous. He is wasting time doing it.”

Angrily Senator McCarthy said Mr. Welch was being unfair. “That may sound funny as all get-out here,” Senator McCarthy said. “It may get a laugh. He knows it is ridiculous. He is wasting time doing it. He is trying to create a false impression. I would like to suggest that after this long series of ridiculous questions, talking about why he wouldn’t go over to the Pentagon and yell out ‘Sic ’em, Stevens,’ that Mr. Cohn should be able to tell what happened after the document was received. That is the only fair thing, Mr. Chairman.”

Just before Mr. Cohn was excused abruptly, Mr. Welch created something of a stir in the committee room by disclosing he had obtained hotel and night club records indicating Mr. Cohn’s expenditures for dinners and parties in New York and Trenton at times when Private Schine was on leave from Fort Dix.

Some of them concerned the Stork Club, but Mr. Cohn swore that Private Schine, had not been there during the time he was assigned to Fort Dix. Some of the other expenditures, he said, represented occasions when he had dined with Private Schine, and, on one occasion, when they had been accompanied by girls.

NOTE: McCarthy was ultimately censured by Congress for his witch hunts, but the atmosphere of suspicion, distrust and guilt by association persists in Washington.

VIETNAM ARCHIVE: PENTAGON STUDY TRACES THREE DECADES OF GROWING U. S. INVOLVEMENT

By NEIL SHEEHAN, JUNE 13, 1971

A massive study of how the United States went to war in Indochina, conducted by the Pentagon three years ago, demonstrates that four administrations progressively developed a sense of commitment to a non-Communist Vietnam, a readiness to fight the North to protect the South and an ultimate frustration with this effort—to a much greater extent than their public statements acknowledged at the time.

The 3,000-page analysis, to which 4,000 pages of official documents are appended, was commissioned by Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara and covers the American involvement in Southeast Asia from World War II to mid-1968—the start of the peace talks in Paris after President Lyndon B. Johnson had set a limit on further military commitments and revealed his intention to retire. Most of the study and many of the appended documents have been obtained by The New York Times and will be described and presented in a series of articles beginning today.

Though far from a complete history, even at 2.5 million words, the study forms a great archive of government decision-making on Indochina over three decades. The study led its 30 to 40 authors and researchers to many broad conclusions and specific findings, including the following:

• That the Truman administration’s decision to give military aid to France in her colonial war against the Communist-led Vietminh “directly involved” the United States in Vietnam and “set” the course of American policy.

• That the Eisenhower administration’s decision to rescue a fledgling South Vietnam from a Communist takeover and attempt to undermine the new Communist regime of North Vietnam gave the administration a “direct role in the ultimate breakdown of the Geneva settlement” for Indochina in 1954.

• That the Kennedy administration, though ultimately spared from major escalation decisions by the death of its leader, transformed a policy of “limited-risk gamble,” which it inherited, into a “broad commitment” that left President Johnson with a choice between more war and withdrawal.

• That the Johnson administration, though the president was reluctant and hesitant to take the final decisions, intensified the covert warfare against North Vietnam and began planning in the spring of 1964 to wage overt war, a full year before it publicly revealed the depth of its involvement and its fear of defeat.

• That this campaign of growing clandestine military pressure through 1964 and the expanding program of bombing North Vietnam in 1965 were begun despite the judgment of the government’s intelligence community that the measures would not cause Hanoi to cease its support of the Vietcong insurgency in the South, and that the bombing was deemed militarily ineffective within a few months.

• That these four succeeding administrations built up the American political, military and psychological stakes in Indochina, often more deeply than they realized at the time, with large-scale military equipment to the French in 1950; with acts of sabotage and terror warfare against North Vietnam beginning in 1954; with moves that encouraged and abetted the overthrow of President Ngo Dinh Diem of South Vietnam in 1963; with plans, pledges and threats of further action that sprang to life in the Tonkin Gulf clashes in August, 1964; with the careful preparation of public opinion for the years of open warfare that were to follow, and with the calculation in 1965, as the planes and troops were openly committed to sustained combat, that neither accommodation inside South Vietnam nor early negotiations with North Vietnam would achieve the desired result.

The Pentagon study also ranges beyond such historical judgments. It suggests that the predominant American interest was at first containment of Communism and later the defense of the power, influence and prestige of the United States, in both stages irrespective of conditions in Vietnam.

And it reveals a great deal about the ways in which several administrations conducted their business on a fateful course, with much new information about the roles of dozens of senior officials of both major political parties and a whole generation of military commanders.

MOTIVE IS BIG MYSTERY IN RAID ON DEMOCRATS

By WALTER RUGABER, JUNE 26, 1972

Moving through the basement after midnight, the guard found strips of tape across the latches of two doors leading to the underground garage.

It was an altogether fit beginning for a first-rate mystery—the raid on the Democratic National Committee headquarters.

In the eight days since, the White House and the Republican party have been embarrassed, the Democrats have sensed a big election-year issue and a major federal investigation has begun. The mystery has involved Republican officials, former agents of the Central Intelligence Agency, White House aides and bewildering assortments of anti-Castro Cubans.

Guard Not Alarmed

There has been talk of telephone taps, spy cameras and stolen files; of obscure corporations and large international financial transactions; of an unsolved raid on a chancery office and on an influential Washington law firm.

The guard, Frank Wills, a tall, 24-year-old bachelor who earned $80 a week patrolling one of the office buildings in the Watergate complex for General Security Services, Inc., was not greatly alarmed when he found the tape.

The high-priced hotel rooms, prestigious offices and elegant condominium apartments within the Watergate development had been favorite targets of Washington’s burglars and sneak thieves for several years.

Along with three present or former cabinet officers and various other Republican leaders, the tenants included the Democratic National Committee. Its offices had been entered at least twice within the last six weeks. But Mr. Wills assumed that the office building’s maintenance men had immobilized the latches. He tore off the strips of tape, allowing the two doors to lock, and returned to his post in the lobby.

“Somebody was taping the doors faster than I was taking it off.”

Ten minutes later, acting on what he now calls a “hunch,” he returned to the basement. The latches were newly taped. So were two others, on a lower level, that had been unobstructed only minutes before.

“Somebody was taping the doors faster than I was taking it off,” Mr. Wills said in an interview later. “I called the police.” His alarm was logged at the central station at 1:52 a.m. on Saturday, June 17.

It took less than 48 hours for the authorities to clamp a fairly tight lid on things. Much of the information that emerged afterward, even on the most pedestrian points, was unofficial or leaked by unnamed sources.

And none of it established motive. Washington went on a speculative binge, but even those running the investigation were said to be confused and uncertain. The available facts offered many possible interpretations.

More Tape Found

First to reach the Watergate were plainclothes members of the Second District Tactical Squad. They went first to the eighth and top floor, where tape was found on a stairway door. Nothing else was amiss, however.

Working their way down, they found more tape on the sixth floor. With guns drawn, they entered the darkened offices of the Democratic National Committee. Crouched there were five unarmed men, who surrendered quietly.

“They didn’t admit what they were doing there,” said John Barret, one of the plainclothes men who handcuffed the five and lined them up against a wall. “They were very polite, but they wouldn’t talk.”

Presumably, there was plenty to talk about—the taped latches, for example.

For one thing, taping the doors was a dead giveaway. Ordinarily, burglars use wooden match sticks. Also, why did anyone bother with the door on the eighth floor?

Furthermore, once the tampering had been discovered, it was risky in the extreme to repeat it. Who did it? And why were two separate basement entrances taped the second time?

Why, in fact, were any? All of the doors open freely from the inside, and once entrance to the building had been gained, an intruder could have left without keys and without setting off an alarm.

Too Many Men

Five men were found in the Democratic offices, which struck those informed in such matters as three or four too many. The five men were charged with burglary and led off to the District of Columbia jail, where they all gave false names to the booking officer. After a routine fingerprint check, they were identified as follows:

Bernard L. Barker, 55 years old, a native of Havana who fled the Fidel Castro regime and became an American citizen. He is president of Barker Associates, a Miami real estate concern.

James Walter McCord Jr., 53, a native of Texas. He is now president of McCord Associates, Inc. of suburban Rockville, Md., a private security agency.

Frank Sturgis, 48, who lost his American citizenship for fighting in the Castro army but regained it later. He has changed his name from Frank Fiorini but is still known under both names. He works at the Hampton Roads Salvage Company, Miami.

Eugenio R. Martinez, 51, a man with $7,199 in his savings account and who works as a notary public and as a licensed real estate operator. He now works for Mr. Barker’s agency and is said to earn $1,000 a month.

Virgilio R. Gonzalez, 45, a locksmith at the Missing Link Key Shop, Miami. He is reported to have been a housepainter and a barber in Cuba, which he fled after Mr. Castro’s takeover in 1959.

All except Mr. McCord left Miami Friday afternoon, apparently on Eastern Airlines flight 190, which arrived at Washington National Airport at 3:59 p.m. Mr. Barker used his American Express credit card to rent a car at that time.

The four men checked into two rooms—214 and 314—at the Watergate Hotel. They are understood to have dined that evening in the hotel restaurant. The hotel connects with the office building through the underground garage.

What Police Seized

The police collected what the five men had with them at the time of their arrest and obtained warrants to search the two hotel rooms and the rented automobile. An inventory included:

• Two 35-mm cameras equipped with close-up lens attachments, about 40 rolls of unexposed 35-mm film, 1 roll of film from a Minox “spy” camera and a high-intensity lamp—all useful in copying documents.

• Two or three microphones and transmitters. Two ceiling panels had been removed in an office adjacent to that of the party chairman, Lawrence F. O’Brien, and it was theorized that the equipment was being installed, replaced or removed.

• An assortment of what were described as lock picks and burglary tools, two walkie-talkie radios, several cans and pen-like canisters of Chemical Mace and rubber surgical gloves, which all five men had been wearing.

• Nearly $6,000 in cash. The money, found in the possession of the five and in the two hotel rooms, included some $5,300 in $100 bills bearing consecutive serial numbers.

Parts of the Democratic headquarters had been ransacked. Mr. O’Brien subsequently said that the party’s opponents could have found an array of sensitive material, but no pattern to the search has been disclosed.

Last Sunday, the Associated Press discovered from Republican financial records filed with the government that Mr. McCord worked for both the Committee to Re-Elect the President and the Republican National Committe.

“Security Coordinator”

The records showed that since January Mr. McCord had received $1,209 a month as “security coordinator” for the Nixon organization, and that since October he was paid more than $600 a month for guard services for the Republican unit.

The following day it was learned that in address books taken by the police from Mr. Barker and Mr. Martinez the name of E. (for Everette) Howard Hunt appeared. Mr. Hunt had worked, as recently as March 29, as a White House consultant.

The police also turned up in the belongings of the five suspects an unmailed envelope that contained Mr. Hunt’s check for $6, made out to the Lakewood Country Club in Rockville, and a bill for the same amount.

The records showed that since January Mr. McCord had received $1,209 a month as “security coordinator” for the Nixon organization.

Both Mr. Hunt and Mr. McCord were members of the Rockville Club, and there were published reports that Mr. Hunt met with Mr. Barker in Miami two weeks before the break-in. The White House said that Mr. Hunt worked 87 days in 1971 and 1972 under Charles W. Colson, special counsel to the president. Mr. Colson has frequently handled sensitive political assignments.

The consultant, who is the author of 42 novels under several pen names, works full time as a writer for Robert R. Mullen & Co., a Washington public relations firm with long-standing Republican connections. The firm’s president, Robert F. Bennett, quoted Mr. Hunt as saying he “was nowhere near that place [the Watergate] Saturday.” The writer has declined public comment, however, and Mr. Bennett has suspended him.

Security Man Dropped

The Republicans quickly discharged Mr. McCord as their security man and denied emphatically that they had had any connection with the raid on the Democratic headquarters.

“We want to emphasize that this man [Mr. McCord] and the other people involved were not operating either on our behalf or with our consent,” said John N. Mitchell, the former attorney general who is now head of the Nixon committee.

Ronald L. Ziegler, the White House press secretary, said that “a third-rate burglary attempt” was unworthy of comment by him and asserted that “certain elements may try to stretch this beyond what it is.”

The White House pointed out that there was no evidence that either Mr. Colson or Mr. Hunt had been involved in any way in the raid on the Democrats, and several high-ranking police officials privately advanced the same view.

The Democratic National Committee, however, filed a $1-million civil suit against the five accused raiders and against the Committee to Re-Elect the President, charging that the Democrats’ civil rights and privacy had been violated.

Mr. Mitchell described this as “another example of sheer demagoguery on the part of Mr. O’Brien.” Mr. O’Brien said that there was “a developing clear line to the White House.

Stories about Spies

More or less simultaneously with the political exchanges, the reports about former spies began to come in. All five of the arrested men were said to have had ties to the Central Intelligence Agency.

Mr. Hunt, operating under the code name Eduardo, was described as the man in direct charge of the abortive invasion of the Bay of Pigs in Cuba in 1961. He is known to have worked for the C.I.A. from 1949 to 1970.

Mr. Barker also worked for the C.I.A. He was reported to have been Mr. Hunt’s “pay master” for the Cuban landing and, under the code name Macho, to have established the secret invasion bases in Guatemala and Nicaragua.

Mr. McCord, too, was a C.I.A. agent. After three years with the Federal Bureau of Investigation, he joined the intelligence unit in 1951 and resigned in 1970. His role in the Bay of Pigs was understood to be relatively minor.

The spy angles led directly to the Cuban refugee angle. It was disclosed that on the weekend of May 26–29, eight men who described themselves as representatives of an organization called Ameritas registered at the Watergate Hotel.

The eight included those arrested in Democratic headquarters except Mr. McCord. It was also disclosed that during that May weekend there was a burglary of the Democratic offices. Ameritas turned out to be an obscure real estate concern in Miami. One of the principals was a close friend of Mr. Barker but none of the arrested men ever owned an interest in the company. A man who does, Miguel A. Suarez, a prominent lawyer in the Cuban community, said that Mr. Barker had made “unauthorized” use of the Ameritas letterheads in making reservations at the Watergate for the eight men.

Search Is on for Four

The F.B.I. began a nationwide search for the four others who stayed there, and the theory grew that if Ameritas was not, as the police had speculated, a right-wing, anti-Castro paramilitary unit, there must be one somewhere.

The Chilean chancery, representing a left-wing government, was mysteriously searched during the night of May 13–14, and the door of a law firm with several prominent Democrats as members was tampered with on the night of May 15–16.

Some of the $100 bills found by the police appear to have been withdrawn from Mr. Barker’s Miami bank. The money had been deposited there in the form of checks drawn on the Banco Internacional, S.A., Mexico City.

There are countless anti-Castro organizations in the Miami area, ranging in size from one member to hundreds, and many of them are devoted to plotting. Among those cited in connection with the break-in was one involving veterans of the Bay of Pigs.

While it was conjectured that a Cuban group might have been seeking to curry favor with the Republicans or to battle leftists, this theory, like all the others, was uncertain.

TEARS AT PARTING

By JAMES T. WOOTEN, AUGUST 10, 1974

Richard M. Nixon, his face wet with tears, bade an emotional farewell to the remnants of his broken administration today, urging its members to be proud of their record in government and warning them against bitterness, self-pity and revenge.

“Always remember, others may hate you,” he told members of his cabinet and staff in a final gathering at the White House, “but those who hate you don’t win unless you hate them—and then you destroy yourself.”

Shortly thereafter, for the last time as president of the United States, he strode up the ramp of the plane that had taken him to the capitals of the world and was flown home to California, where his career in American politics began nearly 30 years ago.

It was 11:35 a.m. here when President Nixon’s letter of resignation was delivered to the office of Secretary of State Kissinger. This is what it said:

“Dear Mr. Secretary: I hereby resign the office of President of the United States. Sincerely, Richard Nixon.”

Richard Nixon waves goodbye to members of his staff as he boards a helicopter, August 9, 1974, the day after resigning the presidency following the Watergate scandal.

Greeted by 5,000

Soon after his departure, while the giant jet was soaring high above the heartland of the country, Gerald R. Ford was sworn in here as the nation’s president.

Despite that new status, 5,000 people greeted his arrival in his native state at El Toro Marine Base. They cheered and applauded when, with his wife, Pat, standing nearby, Mr. Nixon stepped to a waiting microphone, squinted into the brilliant midday heat and said, “We’re home.”

After a few more remarks, a helicopter whisked the former president, Mrs. Nixon, their daughter Tricia and her husband, Edward F. Cox, to La Casa Pacifica, the sprawling seaside villa near San Clemente.

Mr. Nixon’s day began in the mist and rain of a humid Washington morning, when Manolo Sanchez, his long-time valet, laid out the clothes he would wear during the final hours of his tenure as president.

He had determined that he would leave the city as president and, after saying goodbye to the White House servants, he and Mrs. Nixon and their two daughters and son-in-law went downstairs to the spacious East Room, where the men and women who had worked for him were waiting for his farewell remarks.

“You are here to say goodbye to us,” he began, “and we don’t have a good word for it in English. The best is au revoir. We will see you again.”

Then, with his family standing behind him, Mr. Nixon began to speak of many things—of the White House itself, the faithfulness and loyalty of his subordinates there, of his parents, and of the vagaries of human existence.

“This house has a great heart,” he said, “and that heart comes from those who serve.”

He stated his pride in the cabinet he had appointed and the staff he had named, and he conceded that “we have done some things wrong in this administration, and the top man always takes the responsibility—and I have never ducked it.”

“We Can Be Proud”

He went on: “But, I want to say one thing: We can be proud of it—five and a half years—no man or no woman came into this administration and left it with more of this world’s goods than when he came in.”

While he spoke, Mr. Nixon’s eyes brimmed with tears that glistened in the glare of the television lights, and although he occasionally smiled, his remarks were tinted with the sadness his friends say now plagues him.

There was also a moment of irony, when, in discussing vocational integrity, he said that among other craftsmen, the country needs “good plumbers.”

The ornate room, crowded with those who had watched the Watergate scandals grow from a small group of “plumbers” commissioned by Mr. Nixon to find and stop leaks to the media, was quiet except for a scraping chair or two and scattered coughing.

Unlike his quiet, controlled demeanor in his television appearance last night, when he announced to the nation that he would resign, Mr. Nixon was animated in his last White House appearance, moving energetically behind the wooden lectern, gesturing and nodding in punctuation of his remarks.

To Pay His Taxes

The lightest moment in his remarks came when he told the audience that he would like to compensate them monetarily for their services.

“I only wish that I were a wealthy man,” he said. “At the present time, I have got to find a way to pay my taxes.”

There was laughter in the East Room, and some of the quiet but heavy tension was temporarily relieved.

He was calm, though, as he remembered his father, “my old man,” but as he reminisced, his voice grew thick and approached the breaking point.

“I think they would have called him sort of a little man,” he said. “Common man—but he didn’t consider himself that way. . . . He was a great man because he said his job, and every job, counts up to the hilt, regardless of what happens.”

His mother, he said, was a saint about whom no books would ever be written.

Then, Mr. Cox, his son-in-law, stepped over and handed him an open copy of a book. Mr. Nixon pulled a pair of glasses from his coat pocket, put them on and began to read from President Theodore Roosevelt’s diary. The passage he cited was written after the death of his first wife, an event that, according to the diary, “took the light from my life forever.”

Served His Country

“But,” said Mr. Nixon, “he went on, and he not only became president, but as an ex-president he served his country—always in the arena: tempestuous, strong, sometimes wrong, sometimes right, but he was a man.”

At the end of his remarks, he paused and began his, farewell:

“And so, we leave with high hopes, in good spirit and with deep humility, and with very, much gratefulness in our hearts.

“And I can only say to each and every one of you, we come from many faiths, we pray perhaps to different gods, but really the same God in a sense, but I wish to say to each and every one of you, not only will we always remember you, not only will we always be grateful to you, but always you will be in our hearts and you will be in our prayers.”

As they had, when he had entered the room a quarter hour before, the audience stood and applauded. Mr. Nixon and his family stepped down from the curved platform and walked outside to the South Lawn, where Mr. and Mrs. Ford and another crowd of well-wishers were waiting.

The Last Ride

At the end of a scarlet carpet and a corridor of honor guards from the military services, an olive-drab helicopter stood waiting for the last ride from the White House out to Andrews Air Force base and the big, silver-and-blue plane he had dubbed the Spirit of ’76.

Julie Eisenhower kissed her father. David Eisenhower and Mr. Ford kissed Mrs. Nixon. Mrs. Ford kissed Mr. Nixon, and at the last moment, the president reached out for the vice president’s hand, shook it warmly, and then touched Mr. Ford’s elbow with his left hand, like a coach sending in a substitute.

Mr. Nixon mounted the steps to the helicopter, turned and jerked a wave and then lifted his arm in the familiar “victory” gesture.

Several hundred people were at the airport outside Washington to see the president depart. He made no comments there, but once again waved and smiled from the ramp just before disappearing inside.

The engines whined and then screamed and then roared as the plane turned on the tarmac and began moving slowly away from the waving group along the wire fence.

Onboard with Mr. and Mrs. Nixon were Mr. and Mrs. Cox and Ronald L. Ziegler, the press secretary and presidential adviser.

The jet wheeled onto the runway, paused momentarily and then began its takeoff roll toward the west.

THE PRESIDENT’S ACQUITTAL: THE WHITE HOUSE; PRESIDENT SAYS HE IS SORRY AND SEEKS RECONCILIATION

By JAMES BENNET AND JOHN M. BRODER, FEBRUARY 13, 1999

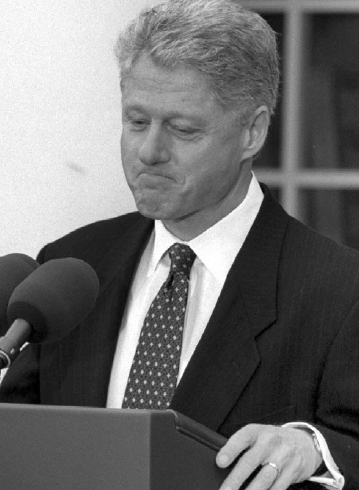

Teetering between remorse and anticipation, President Clinton said today that he felt humbled and “profoundly sorry,” as he pledged to make the most of his latest second chance.

Bill Clinton has survived, again. After the Senate found him not guilty on two articles of impeachment, he tried today to contend with two inescapable questions: At what cost, and for what purpose?

“I want to say again to the American people how profoundly sorry I am for what I said and did to trigger these events and the great burden they have imposed on the Congress and on the American people,” Mr. Clinton said. But, he said, the outcome of his trial presented an opportunity: “This can be and this must be a time of reconciliation and renewal for America.”

Hoping to betray no hint of smugness, the president spent part of Thursday evening in the White House residence working on his five-sentence statement, barely longer than a sound bite. His aides said he revised it this morning in the residence, where he remained until early afternoon.

President Clinton apologizes to the nation during a press conference in the White House Rose Garden on February 12, 1999, several hours after his acquittal in the impeachment trial.

As a strong southerly wind rustled the magnolia trees and puffed into the microphone, Mr. Clinton walked alone from the Oval Office two hours after the Senate finished voting. Speaking slowly and shaking his head for emphasis, he kept his statement short and bittersweet; its essential elements reflected those in a statement of regret he made on Dec. 11, before the House impeached him.

Mr. Clinton took one shouted question, pausing to consider it after he had started walking away: Could he forgive and forget?

He smiled slightly after he turned back to the crowd of reporters, jostling on a springlike day that would later turn stormy and cold. “I believe any person who asks for forgiveness has to be prepared to give it,” he said. Then he left.

Hoping to mold history’s judgment, Mr. Clinton is bent on remaking his protean presidency once again, his friends and advisers say. As of today, it had become something no one could have imagined at his second inaugural two years ago, when he laid his hand on a biblical passage declaring, “Thou shalt be called the repairer of the breach.”

Over 13 months of investigations, revelations and political venom, the president has put his family through misery, taxed the loyalty of his cabinet and his aides, and admitted outright lies to the nation about his affair with Monica S. Lewinsky. The political breach in Washington is gaping.

“I believe any person who asks for forgiveness has to be prepared to give it.”

But for all the personal damage done, Mr. Clinton has prospered politically and his Republican foes have suffered. The president remains firmly in office and resoundingly popular, while Speaker Newt Gingrich and the man who was to succeed him, Robert L. Livingston, are departing for private life.

Besides apologizing again to the country, Mr. Clinton expressed remorse and gratitude today to his staff. Not a single member of Mr. Clinton’s cabinet or staff resigned to protest his behavior.

Via electronic mail, the president’s chief of staff, John Podesta, forwarded to the White House staff an apology from Mr. Clinton, who for all his praise of information technology does not use a computer.

“Your dedication and loyalty have meant more to me than you can ever know,” the message read, in part. “The best way I can repay you is to redouble my own efforts on behalf of the ideals we share, and to make the most of every day we are here.”

After leaving the Rose Garden, Mr. Clinton telephoned several Democratic senators to thank them. Then, in a display of the business-as-usual briskness that carried him through his yearlong crisis, he met with his foreign policy team to begin preparing for an overnight trip to Mexico on Sunday.

Later, Mr. Clinton met in the Oval Office with his public and private lawyers to thank them, and then received a visit from the Rev. Jesse L. Jackson, who has counseled him and supported him politically during his ordeal.

As he told House Democrats at a retreat this week, Mr. Clinton wants to score legislative gains on Social Security, health care and education—even as he fights to win back Congress for the Democrats in 2000. He wants to work with the Republicans who voted to eject him from office, while he tries to eject some of them from office. Some of his allies think that Mr. Clinton has gained the upper hand and will be able to do both.

“This thing has empowered him,” said James Carville, the president’s former campaign manager and informal adviser. “His own party is unified, and the opposition party desperately needs him to get some things done before the election. He’s become stronger and his opponents have become weaker.”

Other Clinton advisers worry that his approval ratings may slide once a public urge to rally around him subsides. They fret that today’s unity might crumble if House Democrats prove less interested in agreement than in fighting Republicans on issues like raising the minimum wage.

Mr. Clinton’s history—as college politician, Arkansas governor, presidential campaigner and president—is a stuttering series of reversals and political fresh starts. Some of his aides divide his presidential terms into as many as five distinct periods of governance and politics, since the Clintons arrived here as bright-eyed outsiders promising intelligence, integrity and compassion. That was only six years ago.

First came a burst of energy and innovation, culminating in the Clintons’ politically disastrous health care proposal and the first Republican Congress in 40 years. There followed a period of drift and despondency, some officials recalled, as Mr. Clinton publicly insisted on his relevance and privately wondered what to do.

By appearing firm and compassionate after the Oklahoma City bombing and then standing up to the Republicans during the government shutdown, Mr. Clinton regained his political footing. Under the influence of his sometime adviser, Dick Morris, he took the initiative again, this time with smaller proposals tested to insure their popularity.

Those ideas carried him to reelection in 1996, but the administration seemed to run out of gas after his second inaugural. Then, as he began to regain his bearings, the disclosures about Ms. Lewinsky swamped him.

Mr. Clinton’s advisers say there is no mystery about what comes next. Mr. Clinton unrolled his policy wish list in his State of the Union message, and he is hoping that success in shoring up Social Security will counterbalance the weight of impeachment.

Some of his aides suspect that the Republicans who tried to remove him will be more scarred by their votes than he is.

“Their votes on impeachment will be in the first paragraph of their obituaries,” said one senior White House official. Mr. Clinton, he said, “will try to get impeachment erased from the first paragraph of his—or at least make it a very, very long paragraph.”

Mr. Clinton did not watch the Senate vote today, his aides said. Instead, Mr. Podesta telephoned him after each ballot to report the outcome. A group of senior aides had gathered in the chief of staff’s office, confident of acquittal but worried that the second charge, obstruction of justice, might draw a majority. “There was a good bit of suspense,” said one who was present.

But, cautioned by Mr. Podesta at the senior staff meeting this morning, Mr. Clinton’s aides avoided any celebration. Only his legal team permitted themselves public grins, as they strolled from the White House to an Indian restaurant for lunch. But even they deferred to appearances, declining a bottle of champagne offered by well-wishers.

“I think, given the circumstances of this matter that’s gone on for this long, we can be relieved it’s over,” said Joe Lockhart, the White House press secretary. “But there’s really nothing to celebrate.”

FIRING FUELS CALLS FOR INDEPENDENT INVESTIGATOR, EVEN FROM REPUBLICANS

By DAVID E. SANGER, MATTHEW ROSENBERG AND MICHAEL S. SCHMIDT, MAY 9, 2017

President Trump’s decision on Tuesday to fire the F.B.I. director, James B. Comey, immediately fueled calls for an independent investigator or commission to look into Russia’s efforts to disrupt the election and any connections between Mr. Trump’s associates and the Russian government.

Calls to appoint an independent prosecutor have simmered for months, but until now, they had been voiced almost entirely by Democrats. Mr. Comey’s insistence that he was pressing ahead with the Russia investigation, and would go wherever the facts took him, had deflected those calls—especially because he was in such open defiance of a president who said the charges were “fake.”

Mr. Comey’s firing upended the politics of the investigation, and even Republicans were joining the call for independent inquiries.

Senator John McCain, Republican of Arizona, who is among the most hawkish members of Congress on Russia, said that he was “disappointed in the president’s decision” and that it bolstered the case “for a special congressional committee to investigate Russia’s interference in the 2016 election.”

He got support from the chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee, Richard M. Burr of North Carolina, a Republican leading what appears to be the most active congressional investigation on Russia. “I am troubled by the timing and reasoning of Jim Comey’s termination,” Mr. Burr said in a statement. It “further confuses an already difficult investigation by our committee,” he said, adding that Mr. Comey had been “more forthcoming with information” than any of his predecessors.

The Democratic vice chairman of the Senate panel, Mark Warner of Virginia, said in a brief interview that Mr. Comey’s firing “means the Senate Intelligence investigation has to redouble its efforts, has to speed up its timeline, because we’ve got real questions about the rule of law.” Even before Mr. Comey was fired, the committee was pressing forward with its investigation. Late last month, it asked a number of high-profile Trump campaign associates to hand over emails and other records of dealings with Russians. Mr. Warner said the committee planned to announce on Wednesday who had complied and who had not.

Officials familiar with the investigation say the committee is prepared to issue subpoenas to get the records. Mr. Warner would not say when, or if, those might come.

Earlier in the evening, he told CNN the committee had sent the Treasury Department a request for financial records of Mr. Trump and a number of associates.

The Justice Department insisted the dismissal had nothing to do with the Russia investigation. Rather, it said, it was a response to how Mr. Comey handled the investigation of Hillary Clinton, and his decision to declare last summer that there was no reason to prosecute her for using a private email server. Yet Mr. Trump’s letter to Mr. Comey made an oblique reference to the Russia investigation that has consumed the early months of his presidency.

James Comey, Director of the F.B.I., is sworn in during the Senate Judiciary Committee hearing at the Dirksen Senate Office building on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C. on May 3, 2017.

“While I greatly appreciate you informing me, on three separate occasions, that I am not under investigation, I nevertheless concur with the judgment of the Department of Justice that you are not able to effectively lead the bureau,” Mr. Trump wrote.

The letter “doesn’t pass any legitimate smell test,” Mr. Warner said.

For weeks, Mr. Trump has turned to his Twitter account to denounce the investigations as a waste of taxpayer money, including in the hours before Mr. Comey testified to Congress last week. His Twitter posts appeared to be direct challenges to an open F.B.I. investigation, a subject presidents have traditionally tried to avoid commenting on publicly.

Whether Mr. Trump was seeking to affect the Russia investigation will now become a subject of argument and a new partisan battle. Some in the White House feared that Mr. Comey’s inquiry, first publicly acknowledged nearly two months ago, could harm the president even if no charges were brought.

At the core of the concern about Mr. Trump’s motive for firing Mr. Comey is whether the White House is trying to delay or derail the F.B.I.’s investigation into Mr. Trump’s associates. Among the former advisers to the president now under investigation are his campaign chairman Paul Manafort, and Roger Stone, a longtime confidant.

Mr. Stone predicted last year that there would be major, embarrassing revelations about Democratic officials, which proved prescient when WikiLeaks published emails from John D. Podesta, Mrs. Clinton’s campaign chairman.

The emails had been stolen by Russian hackers months earlier.

Appearing before Congress in March, Mr. Comey described the F.B.I. inquiry as a counterintelligence investigation, indicating that one question was whether Russia’s government had tried to recruit Mr. Trump’s associates. He said explicitly that one focus was possible collusion between Trump associates and the Russian officials behind interference in the election. Investigations of this type can go on for years, and some Republicans were increasingly concerned that it was creating a cloud over the president and the party that they could not dispel.

Democrats said they had little doubt of what had motivated Mr. Trump to fire his F.B.I. director. Representative Adam B. Schiff of California, the top Democrat on the House Intelligence Committee, said the firing “raises profound questions about whether the White House is brazenly interfering in a criminal matter.”

When Mr. Trump was preparing for the presidency after his election, there was no immediate sign that he would seek to oust Mr. Comey. The F.B.I. director came to brief him at Trump Tower with other intelligence officials, carrying a detailed intelligence report, ordered by President Barack Obama, on Russia’s actions and the intelligence supporting the conclusion that President Vladimir V. Putin was behind them.

Afterward, Mr. Trump said briefly in public that he was persuaded by the evidence.

During that same session, Mr. Comey briefed Mr. Trump on a dossier compiled by a former British intelligence officer that alleged a broad conspiracy between Mr. Trump and Russian officials. None of those charges have been proven, but the briefing immediately associated Mr. Comey with an investigation Mr. Trump has dismissed as a politically motivated witch hunt.

The firing also raised questions about the role of Attorney General Jeff Sessions, a former senator from Alabama and one of Mr. Trump’s earliest supporters. Mr. Sessions recused himself from the Russia investigation in March, after it was revealed that he had provided inaccurate information to Congress about his meetings with the Russian ambassador to the United States, Sergey I. Kislyak. On Tuesday, however, he wrote a letter to Mr. Trump endorsing a memorandum by his deputy, Rod Rosenstein, and making the case for Mr. Comey’s immediate ouster. In that letter, Mr. Sessions did not describe his specific concerns but said, “A fresh start is needed at the leadership of the F.B.I.”

NOTE: President Donald Trump hoped the firing of James Comey as F.B.I. director would quash the investigation into whether or not his campaign conspired with the Kremlin to interfere in the 2016 election, but it had the opposite effect. The stunning move led to the appointment of a special counsel, former F.B.I. chief Robert Mueller, to head an investigation that, as of this writing, continues well into his presidency and which is an object of almost daily public rants by Trump on Twitter and in his speeches.