THE PRISONERS WERE placed in formation, in lines four abreast. Officers led the way, followed by alternating ranks of four black and four white soldiers. The column was ordered to parade through the streets of Petersburg in full view of the town’s remaining civilian population. The roughly 1,500 black and white Union prisoners, who had been captured the day before, July 30, 1864, after their failed assault, were being used to send a strong message: to the men serving in Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, to the remaining white residents of Petersburg, and to the Confederacy as a whole. As the prisoners marched and countermarched through the streets, they were subjected to taunts and verbal abuses from spectators at the street level and on verandas, which offered perhaps the best view of this unusual scene. Lieutenant Freeman S. Bowley recalled years later that once the column entered the city, “we were assailed by a volley of abuse from men, women and children that exceeded anything of the kind that I ever heard.” The cries of “See the white and nigger equality soldiers” and “Yanks and niggers sleep in the same bed!” suggest that the intended message of this interracial march of prisoners had come through loud and clear, accomplishing all it had set out to do and more.1

The order to march both black and white Union prisoners through Petersburg served to remind soldiers and civilians alike of just what was at stake as the American Civil War entered its fourth summer. The torrents of abuse hurled that early Sunday morning were directed first and foremost at the black Union soldiers (now stripped of their uniforms), some of whom were once the property of Virginia slave owners. Their presence on the battlefield reinforced horrific fears of miscegenation, the raping of white Southern women, and black political control that had surfaced at various times throughout the antebellum period and that many had come to believe would ensue if victory were not secured.

The fear that animated the black soldiers as they endured the taunts of their captors and the sting of public humiliation was of a different sort. For these men the recent fight had been an opportunity to finally prove themselves on the field of battle and impress upon both their white officers and the rest of the nation that they were worthy of respect as men, as soldiers and, potentially, as future citizens of a nation reborn out of the ashes of slavery. Now, as they marched through the city, they couldn’t be certain that they would escape the fate of their black comrades who had been executed in the immediate wake of the battle. In addition to the bursts of rage exhibited on the streets by a restless public, black soldiers also had to cope with resentment and anger from many of their fellow white soldiers, who felt humiliated at having to march in formation with them rather than in their normal segregated units, as well as from their own white officers, some of whom chose to lie about their unit identification.2

Once the parade ended, the men were marched to Merchant Island, situated in the Appomattox River, where they awaited transportation to prisons in Richmond and Danville, Virginia, or Salisbury, North Carolina. Some black soldiers fared much worse. Confederate authorities refused to treat them as prisoners and instead allowed area slave owners to review them in hopes of locating and reclaiming fugitive slaves.3

Accounts of what eventually came to be known as the battle of the Crater or Mine tend to ignore or downplay this moment in the overall narrative of the battle. Instead, historians and other writers have tended to focus on the construction of the mine shaft, the early morning massive detonation of 8,000 pounds of explosives that ripped through a Confederate brigade, and the fierce battle that ensued—all of which fits into the scale of violence that had developed by the summer of 1864. On the other hand, the failure to adequately account for the presence of an entire division of United States Colored Troops and what its presence meant to the men who took part in this battle tells us a great deal about how our collective memory of this particular battle and the war as a whole has evolved since 1865. In ignoring this prisoner march of black and white soldiers, however, we fail to understand and appreciate a salient factor of this particular battle, one that was not and could not be ignored by those engaged.

The battle that took place on July 30, 1864, grew out of a costly campaign in Virginia that stretched from the Rappahannock River to the Appomattox between the beginning of May and mid-June. Beginning on May 5 and continuing through the first two weeks of June, General Ulysses S. Grant’s Army of the Potomac (commanded by General George G. Meade) and General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia engaged in some of the fiercest fighting of the entire war. The two armies clashed at such places as the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, the North Anna River, Cold Harbor, and along the defensive perimeter around the city of Petersburg. Although outnumbered two to one, Lee managed to stave off numerous attacks and keep his army between the Federals and the Confederate capital of Richmond. The fierce fighting that defined the Overland campaign cost both armies dearly, especially the Army of the Potomac, which lost upward of 50,000 men; although Lee’s army suffered less, its 33,000 casualties constituted a higher percentage in an army numbered around 60,000.4

Grant had hoped to cajole Lee into a decisive battle that would decide the war in Virginia, but as his army pushed closer to Richmond, his thoughts centered on shifting the fighting south of the James River to Petersburg. Five railroad lines connected Petersburg with the rest of the Confederacy: the Richmond and Petersburg Railroad, the Southside Railroad, Weldon Railroad, the Norfolk Railroad, and the City Point Railroad. Disruption of those lifelines would not only seriously hamper Lee’s operations and jeopardize Richmond but damage the overall Confederate war effort.

Beginning on June 12 the Army of the Potomac moved out from its positions around Cold Harbor. This final turning movement was led by Major General William Smith’s Eighteenth Corps, which moved by ship to Bermuda Hundred while the rest of the army marched to the James River crossings. Once across, the lead elements of Grant’s army were within a day’s march of Petersburg. Lee’s army remained in its positions, convinced that operations would resume in the vicinity of Richmond.

Smith’s Eighteenth Corps, which numbered around 12,500 and included a small division of USCTs under the command of General Edward W. Hinks, reached the outer defenses of Petersburg close to noon on June 15. The defense of Petersburg was left to 2,200 old men and young boys under the command of former Virginia governor Brigadier General Henry A. Wise. Their defenses—called the “Dimmock Line” after Captain Charles H. Dimmock, who commenced construction back in the summer of 1862—consisted of a chain of massive breastworks and gun emplacements that began east of the city on the Appomattox River and ended on the river just west of the city, thus forming a semicircle. The attack on June 15 succeeded in capturing a series of strong artillery positions east of Petersburg, but Smith resisted Hinks’s suggestion to continue the attack and possibly take the city itself. Major General Winfield S. Hancock’s Second Corps arrived overnight while Lieutenant General Pierre G. T. Beauregard transferred units to Petersburg, which brought their numbers to around 14,000. Attacks continued during the next two days, but they failed to break Confederate defenses. Smaller operations continued in mid-June as Union forces severed two minor railroad lines east of Petersburg, but the Southside and Weldon railroads continued to supply Lee’s army, which now numbered around 50,000 and occupied a line some twenty-six miles long between Richmond and Petersburg. Grant’s force constituted an impressive host, hovering around 112,000 troops.5

The constant digging between the two armies resulted in a forward line buttressed by enclosed redans, or forts, plus additional trenches behind the forward line connected by zigzagging communication trenches. The entire system was finally connected to the rear with sunken roads and covered ways, which were vital for shifting men and supplies out of sight of enemy guns. Work was regularly conducted in conditions topping 100 degrees with no rain throughout the period between the battle of Cold Harbor and July 19. With both armies committed to the protection afforded by their earthworks, life in the trenches was reduced to a monotonous regularity.6

A notable exception to this pattern materialized during the final week of June in the center of the Union position, where the two armies were situated barely 100 yards from one another. That sector was under the command of Brigadier General Robert Potter, who commanded a division in Major General Ambrose Burnside’s Ninth Corps. Opposite Potter’s position was situated a brigade of five South Carolina regiments under the command of Brigadier General Stephen Elliott. His brigade, along with a four-gun battery under the command of Captain Richard Pegram, occupied a salient that jutted out from the rest of Major General Bushrod Johnson’s division under the command of Beauregard. Lieutenant Colonel Henry Pleasants of the Forty-eighth Pennsylvania, who had worked as a civil engineer before the war and now commanded the most advanced regiment in Potter’s division, speculated that a mine could be dug under the enemy’s salient and packed with explosives. Potter and Pleasants shared the idea with Burnside, who, once he believed the plan had a chance to succeed, passed the proposal up the chain of command to Meade and Grant. Meade authorized the construction of the mine even though he advocated a more traditional siege operation as opposed to costly frontal and flank assaults. Mining operations commenced on June 25 in a ravine removed from direct observation by the enemy and under the direct supervision of Sergeant Henry Reese.7

The men of the Forty-eighth Pennsylvania worked for one month, from the end of June to the third week in July, before completing a tunnel measuring roughly 500 feet, which branched off into two lateral chambers at a point under the Confederate fort. Once finished, the two chambers were packed with 320 kegs of gunpowder, totaling 8,000 pounds, and these were ready for detonation on July 28. Confederate countermines were attempted in the vicinity, but they proved to be too shallow. Pleasants believed he had “accomplished one of the great things of this war.” He privately scoffed at the chief engineer and other “wiseacres” who failed to provide support for the operation or argued that a mine of such length was not feasible. Perhaps no one had a clearer sense than Pleasants of the mine’s destructive power, and this manifested in his sense of foreboding: “It is terrible however, to hurl several men with my own hand at one blow into eternity, but I believe I am doing right.”8

With the mine close to completion, the Union high command formulated a plan to exploit the results of what promised to be an impressive and destructive explosion. Burnside proposed using Brigadier General Edward Ferrero’s division, which included two brigades of USCTs, to spearhead the attack and exploit what many believed would be a significant gap in the Confederate position. Ferrero’s division was to push into the remains of the fort and swing left and right, sweeping the Confederate lines, followed by the other three divisions in Burnside’s Ninth Corps. One division of the Tenth and one of the Eighteenth Corps stood ready to support the advance. Their goal was to break through the salient and seize a ridge crest overlooking Petersburg some 533 yards beyond. If all went as planned, black soldiers stood a chance of being the first Union soldiers to enter the city of Petersburg.9

The presence of African American soldiers signaled a dramatic shift in the overall policy of the Lincoln administration, which had hoped to save the Union strictly through military means without risking popular support by redrawing deeply entrenched racial boundaries. By the middle of the summer of 1862 it had become clear to military officials in the field and President Abraham Lincoln that both free and enslaved blacks could be utilized for military purposes to preserve the Union; to this end the president issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862 as well as authorization for the enlistment of blacks in the army. While the decision was intended both to increase troop strength and to cripple the Confederate war effort, Lincoln’s decision fueled Northern prejudices and political opposition in 1863 both in the ranks and on the home front.10

Ferrero’s “colored troops” were assigned to Burnside’s Ninth Corps as part of its reorganization in January 1864. The division played a supporting role during the Overland campaign, though it skirmished briefly with Confederate forces on May 15 and 19. Throughout the campaign and into the trenches at Petersburg, black soldiers faced prejudice and discrimination, sometimes from their own white officers who, they believed, feared them as much as their former slave owners. Hard labor continued for Ferrero’s men in the form of picket and fatigue duty as well as the construction of forts and breastworks. The prospect of actual combat and a chance to prove their battlefield prowess would have been eagerly anticipated by many of these men.11

The original plan to utilize Ferrero’s Fourth Division as the vanguard of the Union assault remained in place until the afternoon prior to the attack, when Meade vetoed the use of black troops. While Meade worried that the public might accuse the army of needlessly sacrificing black men if the assault failed, the evidence suggests that he simply did not believe that inexperienced troops had a better chance of succeeding than veteran units. Burnside was devastated. He had carefully selected this unit not because the men were black but because they were fresh and had not been worn down by the monotony of life in the trenches. Meade amended Burnside’s plan, instructing him to use his more experienced white divisions—with Ferrero’s in support—to push straight through the breach in the Confederate lines and head for the crucial position of Cemetery Hill and the Jerusalem Plank Road, which overlooked Petersburg.12

Burnside was a competent commander when given specific instructions, but he found it difficult to improvise; now he was forced to make major revisions to his plan in the final hours preceding the assault. He called on his other three division commanders. In addition to Potter’s division, Brigadier Generals Orlando Willcox’s and James Ledlie’s divisions had been damaged to various degrees in the initial assaults on Petersburg. Burnside asked his three division commanders to draw lots from a hat to decide who would lead. Ledlie came up short and was given the assignment to lead the assault, even though he had already shown signs of incompetence, cowardice, and drunkenness. The final plan called for Ledlie’s division to move into and through the crater with Willcox to follow on the left and Potter on the right to prevent the Confederates from counterattacking. Those units included Robert Ransom’s North Carolina brigade, now under the command of Colonel Lee McAfee, on Elliott’s left and Henry Wise’s brigade, now under the command of Colonel John T. Goode, to his right. Artillery support was provided by Captain Richard Pegram’s four-gun battery, positioned with Elliott’s brigade. The assault was set for the early hours of July 30, with the mine to explode at 3:30 a.m.13

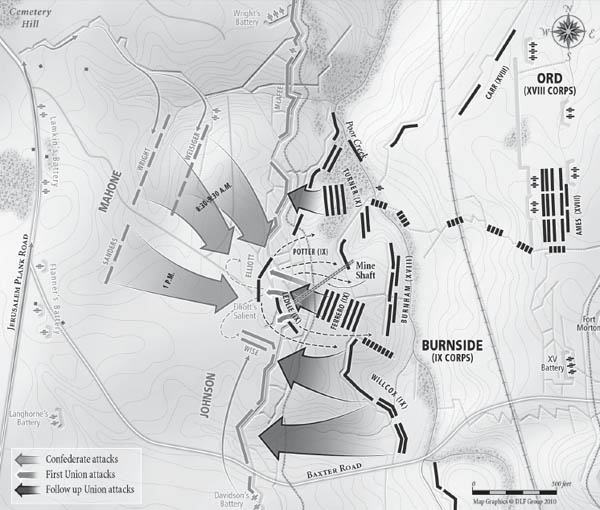

Map of the battle of the Crater, July 30, 1864. (David Fuller/DLF Group)

The mine explosion from behind Union lines. (Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel, Battles and Leaders [New York: Century, 1887–88], 4:561)

Because of a deficient fuse line, the explosion and subsequent attack set for 3:30 was delayed until roughly 4:44 a.m. Sergeant William Russell of Wise’s brigade first “herd a tremendous dull report” and then “felt the earth shake beneath me.” He described the immediate aftermath of the explosion as “an awful scene.” Private John W. Haley in the Seventeenth Maine Regiment later described the explosion: “The most infernal din and uproar that ever greeted mortals crashed around us.” The massive explosion left a hole in the ground 150 to 200 feet long, 60 feet wide, and 30 feet deep, and killed or wounded 278 men in Elliott’s brigade plus 30 gunners in Pegram’s battery.14

The paucity of accounts from Elliott’s South Carolina brigade attests to the destructiveness of the explosion. Many were killed outright or buried alive in their sleep. Lieutenant Pursley of the Eighteenth South Carolina had just gone to sleep in a bombproof when “the first jar I felt I thought it was a boom had lit on my little boom proof. Just as I lit in to the ditch there came another blast & God only knows how high it sent me.” With a bit of literary flair, Pursley described how “I spread out my wings to see if I could fly but the first thing I knowed I was lying on top of the works.” In a letter to the parents of John W. Callahan of the Twenty-second South Carolina, Daniel Boyd conveyed the destructive power of the explosion by illustrating the conditions in which their son was discovered: “J W Calahan Was Kild by the blowing up of our breast Works he was buried wit[h] the dirt. When they found him he was Standing Straight up the ditch there was one hundred kild and buried with the explosion.”15

The Union assault began with a massive artillery barrage along a front of nearly two miles. After a delay of somewhere between ten and fifteen minutes, Ledlie’s two brigades, commanded by Brigadier General William F. Bartlett and Colonel Elisha G. Marshall, pushed toward the scene of the explosion, where they encountered a horrific sight. Rather than moving quickly through the crater and on to the vulnerable crest of Cemetery Hill, both brigades halted on the edge of the crater, in awe of the destruction and as a result of not having received orders from Ledlie to move quickly through the breach in the Confederate line. Precious time was wasted digging Confederates out of the dirt and collecting souvenirs from the dead. “The scene was horrible,” recalled Stephen Weld. “Men were found half buried; some dead, some alive, some with their legs kicking in the air, some with the arms only exposed, and some with every bone in their bodies apparently broken.” Eventually, the two brigades pushed farther and took up position on the far side of the crater. Brigade commanders seemed uncertain as to their goals, largely because of the absence of General Ledlie, who failed to accompany his men and instead removed himself to a bombproof, where he drank away the morning.16

Within thirty minutes of the explosion, Ledlie’s men had maneuvered over the steep western wall of the crater and taken up a position in the complex chain of traverses that emanated out. One final push may have been sufficient to break the Confederate position, but Marshall’s and Bartlett’s brigades hesitated. At the same time Confederate batteries located in close proximity to the crater commenced with a deadly crossfire that frustrated plans for a further advance and prevented units from continuing to move into the vicinity. Adding to the Federals’ difficulties, once the initial shock of the explosion had subsided, the remnants of Elliott’s brigade and other Confederate units took up a defensive position in the shallow trenches and traverses and applied as much firepower on the advancing brigades as possible.

As Ledlie’s division struggled to advance beyond the pit, the two brigades from Potter’s Second Division, under the commands of Brigadier General Simon Griffin and Colonel Zenas Bliss, moved to a position just north of the crater to protect the First Division’s right flank. Although the units were able to extend the overall front, they met fierce resistance from both the remainder of the Seventeenth South Carolina and Colonel McAfee’s North Carolinians, who maneuvered into position to secure gaps in the line resulting from the extreme casualties in Elliott’s brigade. Within a short time an officer in the Twenty-fifth North Carolina observed that the Federals “had planted seven stands of colors on our works.” Meanwhile, on Ledlie’s left the division of Orlando Willcox attacked, with the First Brigade under the command of Brigadier General John Hartranft in the lead. Hartranft’s brigade occupied about 100 feet of trenches before Henry Wise’s Virginia brigade, along with remnants of South Carolina units, checked it. Most of the men were pinned down in the pit with little room to maneuver or organize; as one Union soldier noted simply, it “proved more destructive to us than to the enemy.” Within one hour of the mine explosion, close to 7,500 Union soldiers were defending a perimeter not much larger than the outlines of the crater itself. At the height of the Union assault, the three divisions advanced to occupy at least two separate Confederate lines beyond the confines of the crater.17

At approximately 8:00 a.m., the two brigades in Ferrero’s Fourth Division were ordered into the mix. The First Brigade, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Joshua K. Sigfried, led the way, with the Thirtieth USCT, under the command of Colonel Delavan Bates, in the vanguard. Once out of the Union lines, the brigade made its way over roughly 150 yards of open ground, all the while taking enfilading fire from Confederate rifles and artillery. A few of the lead units in the brigade were diverted to the right of the crater and into a maze of Confederate rifle pits and entrenchments, while the rest of the brigade was forced into the horror of the pit itself, which was quickly becoming a cauldron of death. Colonel Henry G. Thomas also faced the challenge of moving the Second Brigade away from the escalating bloodbath inside the crater, but was able to organize some of his men for an advance. Together, Thomas and Sigfried moved elements of their commands, along with scattered units in the vicinity, into the confusing chain of rifle pits, trenches, and covered ways. As they made their way forward, they mistakenly fired on Griffin’s men, who were still occupying the position they had taken as a result of their unsuccessful advance on Cemetery Hill earlier in the morning. Once in position, both Sigfried’s and Thomas’s brigades made an attempt to advance, but were met with stiff resistance.18

The second Union wave included the division of USCTs under the command of Brigadier General Edward Ferrero. (Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel, Battles and Leaders [New York: Century, 1887–88], 4:552)

Any opportunity for a concerted advance was quickly lost as Brigadier General William Mahone arrived with two brigades from his division. Mahone’s division was situated about one mile southwest of the crater at the time of the explosion, when he was ordered by Lee to move reinforcements to buttress the line. Mahone ordered Colonel David Weisiger’s Virginia brigade and Lieutenant Colonel Matthew R. Hall’s Georgia brigade to move to Cemetery Hill. These units advanced down the Jerusalem Plank Road until they turned east along a covered way to a ravine that branched north and west of the crater. As the two brigades rushed to take up position, Mahone ordered Brigadier General John C. C. Sanders’s Alabama brigade to the front. Weisiger’s Virginians took up a north-south line of battle that faced the crater to the east, with Hall’s Georgians extending the line farther. At approximately 9:00 a.m., just as the advanced Union units were organizing a final assault toward the Jerusalem Plank Road, Weisiger was ordered forward by Mahone.19

Mahone’s Virginians—along with scattered units of North and South Carolinians—were ordered to fix bayonets and not to fire until they reached the enemy line just 200 yards away. They immediately encountered the enemy and responded with heightened ferocity owing to the rumors that Ferrero’s men were heard shouting, “Remember Fort Pillow!” and “No quarter!”—a reference to the reported execution of black soldiers in April 1864 at Fort Pillow, Tennessee. Weisiger’s brigade engaged Ferrero’s men as well as a handful of men in Griffin’s brigade in close hand-to-hand fighting before the raw black soldiers were forced to retire back into the crater. “Instantly the whole body broke,” recalled Bowley of the Thirtieth USCT, “and went over the breastworks toward the Union line, or ran down the trenches towards the crater.” As Weisiger pushed his men in pursuit of the now-retreating Federals, Mahone ordered Hall’s Georgia brigade to attack against the southern rim of the crater. Its initial attack repulsed, the brigade was forced to take up a position behind Weisiger.20

At 1:00 p.m. Mahone ordered Sanders’s Alabama brigade into the mix. The 630 men in this unit were able to advance directly to the rim of the crater, forcing Union commanders to scrap any attempt at an orderly retreat. Desperate hand-to-hand fighting ensued within the heated cauldron as both white and black Union soldiers attempted to maintain some semblance of order. The attack proved to be the final assault of the battle; Confederates gradually gained control of the crater as Union soldiers either surrendered or in desperation attempted to flee back to their lines. An open field of some 100 yards, according to a soldier in the Fifty-first New York Infantry, “was completely swept by the enemy’s Artillery and Infantry, some few of them tried it but the most of those that made the attempt were either killed or wounded.” Federal units stationed in between the crater and their own lines were given the job of slowing down the stream of frightened white and black soldiers. Black troops who surrendered as well as white officers who commanded black units faced an uncertain future.21

The official report identified 3,826 Union casualties out of 16,722 engaged, comprising 504 killed or mortally wounded, 1,881 wounded, and 1,441 missing and presumed to be prisoners of war. Ferrero’s Fourth Division accounted for 41 percent of the total casualties, though it constituted only 21 percent of the men engaged. Confederate casualties were significantly lighter. Out of a total force of roughly 10,000 engaged at the Crater, 361 were killed or mortally wounded, 727 wounded, and 403 missing.22

In the days following the battle, the two armies reorganized and worked feverishly to extend their earthworks, while the men who took part in the fight attempted to make sense of an experience that deviated sharply from previous battles. Surviving letters and diaries follow a pattern in their tendency to concentrate on specific themes that emerged as a result of the scale of the initial explosion and the violent combat that took place on a landscape turned otherworldly by the large chunks of soil, body parts, and debris scattered about.

Soldiers recalled in great detail the nature of the fighting in and around the crater. The close proximity of the fighting was due in large part to the size of the pit created by the explosion, along with adjacent earthworks and traverses, and the nature of the Union attack itself, which left a large percentage of its men confined within the crater’s outer rim and packed tightly within the extended earthworks. David Holt of the Sixteenth Mississippi judged the battle to be the “most horrible sight that even old veterans . . . had ever seen” and compared it to “the bloody ditch at Spotsylvania and the Yankee breastworks at Chancellorsville.” For the men in Union ranks confined within the crater itself there was both the constant pressure of Confederate resistance as well as highly accurate artillery. Brigadier General William Bartlett, who was taken prisoner at the end of the battle, recalled that the enemy “threw bayonets and bottles on us” while John Haley felt as though “every gun in the defense of Petersburg swept that spot.”23

Accounts of the battlefield after the fighting ended attest to the brutality of the combat within a closely defined area of the landscape around Elliott’s Salient. Lee’s men were forced to rebuild their lines while they buried large numbers of comrades as well as the enemy. “After the Battle was over they were lying in our entrenchments in piles blacks whites,” recalled Lieutenant Colonel Matthew Love of the Twenty-fifth North Carolina, “and all together lying in piles three and four deep.” Private Dorsey Binion of the Forty-eighth Georgia Infantry painted a graphic picture of the battlefield for his sister: “The whole face of the works was litterly strewn with dead negroes and our men.”24

The delays in agreeing to the terms of a truce added to the ghastly sights that soldiers on both sides witnessed and recorded. The men were unable to reach out to their wounded comrades until the morning of August 1; the hot temperatures and grueling summer sun added to the number of deaths during those crucial hours. Soldiers detailed to collect the dead, such as Hamilton Dunlap of the 100th Pennsylvania Infantry, were forced to use their shovels to pick up the bodies, which by then “were all maggot-eaten.” Only in death were racial distinctions no longer observable: “Men cut in a thousand pieces and as black as your hat! You could not tell the white from the black by their hair.” Adam Henry recalled wandering the battlefield but quickly succumbed to the “awful Smell” emanating from a pile of 300 corpses, which had severely deteriorated owing to the scalding heat and sun.25

While the scale of violence witnessed at the Crater fit into the broader narrative of a war whose brutality had surpassed what many believed possible in 1861, the presence of USCTs constituted a fundamental shift in the conflict for the men in the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia. For black Union soldiers in the Ninth Corps, their inclusion in the operation offered them the most direct opportunity to assist in the destruction of slavery. In doing so, they would not only help preserve the Union but push the barriers that prevented them from enjoying the benefits and civil rights of full citizenship. Such a scenario was only possible if black men asserted themselves on the battlefield in a full demonstration of their worth as soldiers and as men. By 1864 the battlefield had become a dangerous proposition for black Union soldiers following the announcement from Confederate officials that black soldiers would be treated as slaves and their white officers executed for inciting slave rebellion. As the men of the Fourth Division moved into position late in the evening of July 29, they were encouraged to “Remember Fort Pillow.”26

Black Union soldiers shared in the disappointment surrounding defeat with their comrades in the other three divisions, though their bravery on the battlefield was demonstrated in the high casualty count as well as their participation in some of the farthest advances to take place on the morning of July 30. Unfortunately, the historical record is slim owing to their heavy losses as well as the high illiteracy rates that characterized “colored” regiments. The handful of accounts that are available highlight the harsh treatment accorded to black troops at the hands of Confederates. Sergeant Rodney Long of the Twenty-ninth USCT, who spent seven months imprisoned in Danville, Virginia, recounted that he and his comrades “suffered terribly.” Fellow inmate Isaac Gaskin recalled, “I was punished severely on account of my color” and estimated that out of 180 colored prisoners only 7 survived the ordeal.27

Although accounts from the survivors of Ferrero’s division describe the horrors of battle and the experience of witnessing comrades executed following their surrender, they do not lose sight of the broader collective goal. Survivors of the Crater as well as other campaigns viewed their sacrifice and valor on the battlefield as an integral component in a transformation of American society that would ultimately result in the rights of full citizenship. A soldier in the Forty-third USCT stated proudly, “No longer can it be said that we have no rights in the country in which we live because we have never marched forward to its defense,” while a comrade took pleasure in the fact that he had “helped sustain the nation’s pride.” Chaplain White of the Twenty-eighth USCT looked even further into the future, anticipating that “the historian’s pen cannot fail to locate us somewhere among the good and great, who have fought and bled upon the altar of their country.”28

African American men in the ranks understood that a broad transformation in beliefs among white Americans would not come about easily as they struggled for recognition on the battlefield. They received little notice from Northern newspapers, which reported on their presence in passing if they were mentioned at all. What coverage there was tended to fall along political lines. The Leavenworth Conservative praised their performance in the face of overwhelming resistance and fire while the Democratic Putnam County Courier of Carmel, New York, declared: “Nothing in the details of the battle yet received tends to extenuate the conduct of the negro troops, or to relieve the officers having immediate direction of the operation, from the accusations of blundering.” Most were influenced by accounts from the field, which offered minimal praise of the performance of USCTs. The Christian Recorder reported, “The enemy finally succeeded in causing a panic in the sable ranks” while the Baltimore Sun proclaimed in bold print, “The Colored Troops Falter.” Readers of Philadelphia’s Daily Evening Bulletin would have been hard-pressed to find anything positive in the paper’s coverage of the movements of the Fourth Division: “Their officers cheered them on; they moved a little further forward, again faltered, were again urged to go forward by their officer; still they faltered; entreaties changed to threats, but both were alike useless.” Rare was the favorable coverage found in Harper’s Weekly on August 20. The reporter praised USCTs for their performance at Petersburg, inquiring of readers “whether any soldiers would have fought more steadfastly and bravely and willingly than the colored troops in the Union army?”29

Private Louis E. Martin of Company E, Twenty-ninth USCT, a former slave from Arkansas who enlisted in Illinois, lost his right arm and left leg at the Crater. (RG94, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, National Archives, Washington, D.C.)

Negative portrayals of USCTs’ fighting abilities or no newspaper coverage at all reflected deeply ingrained racial prejudices that were pervasive throughout the North. The appointment of white officers to command black soldiers was intended to assuage these racial concerns about the physical, mental, and moral character of black soldiers, but although these men were positioned to work as advocates for USCTs, they often succumbed to the very same prejudices. Very few officers originated from within abolitionist circles; most no doubt hoped to take advantage of the opportunity for increased pay as well as promotion in rank. Mixed motivations and the desire to reassure their families as well as the general public of their own competency as officers led to mixed reviews. “They went up as well as I ever saw troops,” claimed Colonel Henry G. Thomas, but then he qualified his praise: “They came back very badly. They came back on the run, every man for himself.” Captain James A. Rickard, who served in the Nineteenth USCT, asserted, “The charge of Ferrero’s division . . . and temporary capture of their interior works . . . is a record to win back the previously prejudiced judgment of the president, cabinet generals, and officers of the Army of the Potomac, who up to this time had thought negroes all right for service in menial capacity.” With the exception of some officers who were able to cast off much of their racism to develop strong relationships with black men and acknowledge their worth as soldiers, it is likely that the assessments of most white commanders were based on facile observations that merely solidified long-standing assumptions.30

While the assessment of white officers was mixed regarding the USCTs’ performance at the Crater, there was very little ambivalence outside of the Fourth Division in soldiers’ general opinions of how the battle had been conducted. Soldiers shared their frustrations in letters to family members back home, threatening not to reenlist or vowing to vote for the Democratic nominee in the upcoming presidential election. More specifically, soldiers in the other three Ninth Corps divisions and throughout the Army of the Potomac directed their frustrations at the Union high command, including generals Meade, Grant, and Burnside. A soldier in the Thirty-fifth Massachusetts was convinced that “there were men enough to eat the Rebs up if they had been put in” but concluded that jealousy prevented Meade from fully supporting Burnside’s attack. A soldier in the Seventeenth Maine observed that “with Grant in command we have been in front of Petersburg as long, aye longer than McClellan sat in front of Richmond.” Compared to Grant, this soldier opined, McClellan was a “humane general and tried to avoid useless slaughter of his men.”31

Added to the deep-seated racial prejudices already present within the ranks, the emotional pains of defeat and the growing sense of frustration with the course of the war made it easy to place the blame for the disaster at the Crater at the feet of the USCTs. A soldier in the Thirty-sixth Massachusetts spoke for many of his white comrades when he observed that the USCTs “skedaddled” in the face of Confederate pressure and went on to suggest, “If it hadn’t been for them we should have occupied Petersburg yesterday.” Although Charles Mills praised the leadership of the white officers, he noted that the black troops “were not worth a straw to resist” and “ran like sheep.” “A short delay of an hour, of a single hour, or the unaccountable panic that seized the niggers,” recalled Edward Cook in the 100th New York Infantry, “lost us a battle, which if it had been gained by us, would have proved to be the most important and decisive one of the campaign either in this department or any other.” He concluded, “Everybody here is down on the niggers.” Such language worked to confirm white soldiers’ own assumptions about the physical and moral shortcomings of black men, assumptions that many on the home front, grown weary of war, reinforced.32

Union soldiers focused specifically on the “panic-stricken retreat” of the USCTs as the moment when the battle was lost, but failed to include the fact that various units had managed to maneuver themselves in a forward position just as Mahone’s counterattack began. Many white soldiers, such as Edward Whitman of the Third Division, captured the moment by characterizing the soldiers as “terror-stricken darkies” who “dropped their arms and fled without dealing a blow, embarrassing the white troops around them.” One soldier wrote openly of an order to “fix Baonetts to stop” the retreating soldiers, and Edward Cook suggested that the heavy casualty count was caused in part by “white troops firing into the retreating niggers.” Cook may have been referring to an incident, which took place after Mahone’s charge, that left both white and black soldiers hopelessly trapped in the crater. According to George Kilmer, his fellow white soldiers were seized with panic “that the enemy would give no quarter to negroes, or to the whites taken with them.” “It has been positively asserted,” continued Kilmer, “that white men bayoneted blacks who fell back into the crater . . . in order to preserve the whites from Confederate vengeance.” The inordinate amount of blame leveled at one of the four divisions participating in the assault suggests that serious racial prejudice still existed among the troops, notwithstanding the growing acceptance that the abolition of slavery was necessary to maintain the Union.33

Albeit for very different reasons, Confederate soldiers who fought at the Crater also achieved a remarkable level of consensus as they assessed the fighting that took place on July 30. The novelty of the mine explosion under unsuspecting soldiers in the predawn hours confirmed to most Confederates, as well as those who read about the battle in newspapers, that the Lincoln administration and the North had abandoned any sense of morality and decency. The relative ease with which Confederates were able to retake the salient translated into a firm belief that Grant’s formidable host could be resisted at least for the immediate future. In addition, their overwhelming faith that General Lee could successfully resist Grant’s offensives around Petersburg left open the possibility that Northern voters might grow weary of a protracted war and replace Lincoln with someone else (perhaps George B. McClellan) in the November election. Such a result might ultimately lead to peace and independence. John F. Sale, who served in the Twelfth Virginia, asserted that although “he [Grant] has a tremendous army” and “has outnumbered us two to one all this time . . . , for all that he has gained no decided advantage.”34

More important, the presence of an entire division of armed black men in blue uniform on a battlefield situated near a large civilian population proved decisive in shaping the accounts penned by the men in the Army of Northern Virginia in the wake of the battle. The massacre of USCTs by Confederates at the Crater, as well as how they assessed the presence of black soldiers, must be understood within a broader narrative of slave insurrection and the perceived threat to a social, political, and economic hierarchy based on white supremacy. The consensus achieved in their post-battle accounts can best be understood when analyzed as an extension of long-standing fears attached to the constant threat that armed blacks posed throughout the antebellum period and the roles and responsibilities that white Southerners—slaveholding and nonslaveholding alike—assumed in maintaining a slave-based society.

The responsibilities that white Southerners assumed in defending their families from armed black men had roots in their collective memories and, most important, their fears, both real and imagined, of slave insurrections that had been shaped over the course of the nineteenth century by events in the United States and abroad. While Nat Turner’s deadly insurrection in Southampton County, Virginia, in August 1831, which took the lives of over sixty men, women, and children, loomed large, white Southerners (especially slaveholders) also remembered failed attempts in Richmond led by Gabriel Prosser (1801) and in South Carolina by Denmark Vesey (1823) and closely followed the news from the West Indies. This was an area that experienced continual violence in places like Barbados (1816) and Demerera (1823). The steps taken by British abolitionists to end slavery in this region helped to reinforce assumptions held by white Southerners regarding how to understand and prevent slave unrest. Most important, the agreement among slaveholders in the Caribbean that agitators in England were to blame for slave unrest provided slave owners in the United States with a rationale for the actions of their own supposedly loyal and obedient slaves.35

Turner’s insurrection reinforced a need for vigilance that did not compromise paternalistic assumptions that white Southerners believed bound them to their slaves. It was no coincidence that Turner’s actions occurred shortly after the publication of William Lloyd Garrison’s Liberator in January 1831, and slaveholders were quick to point the finger. Even after Turner’s capture and execution, fears did not subside as news spread of another insurrection in Jamaica involving 60,000 slaves followed closely by the decision of the British Parliament to abolish the institution throughout the empire.36

The sectional disputes of the 1840s and 1850s offered a continual reminder of the dangers posed by outside agitators and a hostile federal government. Slave patrols and state laws were meant to delineate racial boundaries and exercise tighter control of the region’s black population and consequently bound white Southerners ever more closely to one another. John Brown’s raid at Harpers Ferry in October 1859 and the election of the nation’s first “black” Republican as president convinced many in the slaveholding South of the necessity of secession as the only solution that could protect the institution of slavery and ensure their own continued security. The men who defended Petersburg and its civilian population on that hot July day not only understood the nature of the threat that black soldiers posed but, more important, they understood what needed to be done in response.37

Lee’s officers and men were already engaged in heated combat by the time Ferrero’s division entered the battle. For the survivors of Elliott’s South Carolina brigade, as well as the other units in the immediate vicinity of the Crater, the first sign of the black troops was their battle cry. Thomas Smith vividly recalled that the men “charged me crying no quarter, remember Fort Pillow.” The majority of Confederate accounts include references to Fort Pillow, though it is impossible to know how many actually heard such a battle cry given the noise and confusion on the battlefield. The sight of the black soldiers alone would have been sufficient to change the very nature of the reaction of Lee’s men. “It had the same affect upon our men that a red flag had upon a mad bull,” was the way one South Carolinian who survived the initial explosion described the reaction of his comrades. David Holt of the Sixteenth Mississippi remembered, “They were the first we had seen and the sight of a nigger in a blue uniform and with a gun was more than ‘Johnnie Reb’ could stand. Fury had taken possession” of Holt, and “I knew that I felt as ugly as they looked.” Anyone with even a modicum of experience reading Civil War letters and diaries appreciates that soldiers rarely shied away from conveying to loved ones the horrors of battle and their hatred of the enemy, but in this case it is important to keep in mind that Confederates did not perceive USCTs as soldiers. The harsh language used to describe black soldiers not only worked to dehumanize these individuals, it also opened up the possibility of violent and swift retaliation.38

Many Confederates relished the opportunity to share their experiences in the Crater fighting Ferrero’s division and they did so in a way that bordered on cathartic. The vivid descriptions suggest that this killing was of a different kind, given the nature of the enemy. These men were perceived as slaves and by extension fell outside the boundary of ordinary rules of warfare. “Our men killed them with the bayonets and the but[t]s of there guns and every other way,” according to Laban Odom, who served in the Forty-eighth Georgia, “until they were lying eight or ten deep on top of one enuther and the blood almost s[h]oe quarter deep.” Another soldier in the Forty-eighth Georgia described the hand-to-hand combat: “The Bayonet was plunged through their hearts & the muzzle of our guns was put on their temple & their brains blown out others were knocked in the head with butts of our guns. Few would succeed in getting to the rear safe.”39

Both the horror of battle and rage at having to fight black soldiers must have been apparent to the mother of one soldier when she learned that her son “shot them down until we got mean enough and then rammed them through with the Bayonet.” Another soldier admitted, “Some few negroes went to the rear as we could not kill them as fast as they past us.” Lieutenant Colonel William Pegram described in great detail for his wife situations in which black soldiers “threw down ther arms to surrender, but were not allowed to do so. Every bombproof I saw had one or two dead negroes in them, who had skulked out of the fight, & been found & killed by our men.” The sharing of these incidents with loved ones back home reinforced the connection between the battlefield and home front and provided soldiers with a clear understanding of what they were defending their families from. White Southerners may have been especially vivid in their recollections to the females in their families as a reminder of what emancipation would likely mean to their physical safety and honor.40

The use of black Union soldiers served as a rallying cry for Confederates who did not participate in the battle; writing about the battle served as an outlet through which they could express their resentment and anger over the use of black soldiers. Describing how “our men bayoneted them & knacked ther bra[i]ns with the but[t] of their guns,” as did Lee Barfield, may have been the next most satisfying thing to being there. Even A. T. Fleming, who served in the Tenth Alabama but missed the battle due to illness, could not help but allow his racist preconceptions to pervade a very descriptive account in which Confederates “knocked them in the head like killing hogs.” Perhaps commenting on the dead black soldiers on the battlefield or the prisoners, Fleming described them as the “Blackest greaysest [greasiest] negroes I ever saw in my life.” Stationed at Bermuda Hundred during the battle, Edmund Womack wrote home to his wife, “I understand our men just chopped them to pieces.” For the soldiers who did not take part in the fight at the Crater, sharing battle stories with families bound them more closely with those who did and brought to life the emancipation policies of the Lincoln administration.41

Once the salient was retaken, Confederate rage was difficult to bring under control. Accounts written in the days following the battle rarely shied away from including vivid descriptions of the harsh treatment and executions of surrendered black soldiers. Jerome B. Yates of the Sixteenth Mississippi recalled, “Most of the Negroes were killed after the battle. Some was killed after they were taken to the rear.” “The only sounds which now broke the silence,” according to Henry Van Lewvenigh Bird, “was some poor wounded wretch begging for water and quieted by a bayonet thrust which said unmistakably ‘Bois ton sang. Tu n’aurais de soif’ [Drink your blood. You will have no more thirst].” James Verdery simply described “a truly Bloody Sight a perfect Massacre nearly a Black flag fight.” It would be a mistake to reduce these accounts to examples of uncontrolled rage in the face of these black combatants. The level of violence exhibited toward black Union soldiers served no tactical purpose, but allowed Confederates to vent their fury in the face of what they perceived to be a racial order turned upside down and a direct threat to their own communities and families. Indeed, the proximity of the battlefield to the city of Petersburg would have given Confederates a clear sense that they were defending a civilian population from a slave uprising, which further fueled their anger.42

We should not interpret the massacre of black soldiers at the Crater as simply a function of collective rage; rather, it should be viewed as a measured response. Analyzing the Confederate response at the Crater alongside slave rebellions extending back to the beginning of the nineteenth century opens up the possibility of a more nuanced explanation. An 1816 rebellion on the island of Barbados resulted in the execution of roughly 200 slaves, and in Demerera (1823) another 200 slaves were executed following a failed rebellion. Closer to Petersburg, roughly 200 slaves were either publicly tortured or executed following Turner’s Rebellion in 1831. Such violent responses served a number of purposes. Most notably they sent a strong message to the slave community of who was in control, that such behavior would not be tolerated, and that such actions had no hope of succeeding. A direct and brutal response would also work to drain any remaining enthusiasm for rebellion. Applying this framework to the Crater allows us to move beyond the mere fact of rage to better discern the intended consequences of the scale of the violence meted out to black soldiers.43

The lessons of Turner and Brown also convinced white Southerners that unless agitated by meddling abolitionists, their slaves were content and would remain loyal. Such a view provided an avenue for Confederates to explain away apparent acts of bravery and skill exhibited on the battlefield on the part of USCTs. John C. C. Sanders, who commanded the Alabama brigade in Mahone’s division, was forced to admit that the “Negroes . . . fight much better than I expected.” However, he was quick to qualify this statement with the conviction that “they were driven on by the Yankees and many of them were shot down by the latter.” Any acknowledgment of soldierly qualities in USCTs threatened long-standing assumptions regarding the dependent nature of the black race and the paternal justification for slavery itself. J. Edward Peterson, who served as a band member in the Twenty-sixth North Carolina, described the black soldiers at the Crater as “ignorant” and like Sanders assumed they were forced to fight by the Yankees. Perhaps in light of a paternalistic self-perception, Peterson went on to conclude that because of this they did not deserve such harsh treatment by Confederates following the battle. Peterson seems to be one of few who held this view.44

Not surprisingly, as a result of their experience fighting black soldiers, many Confederates experienced a renewed sense of purpose and commitment to the cause. Years after the war, Edward Porter Alexander remembered that the “general feeling of the men towards their employment was very bitter.” According to Alexander, “The sympathy of the North for John Brown’s memory was taken for proof of a desire that our slaves should rise in a servile insurrection & massacre throughout the South, & the enlistment of Negro troops was regarded as advertisement of that desire & encouragement of the idea to the Negro.” Paul Higginbotham of the Nineteenth Virginia reminded his relatives back home that many of his comrades believed that “old Abe will be defeated for President. . . . I am confident we will yet again gain our independence,” asserted this soldier defiantly, “if we are true to our cause and Country.” William Pegram also acknowledged the perceived threat when he noted, “I had been hoping that the enemy would bring some negroes against this army.” And now that they had, “I am convinced . . . that it has a splendid effect on our men.” Pegram concluded that though “it seems cruel to murder them in cold blood,” the men who did it had “very good cause for doing so.” According to Pegram’s most recent biographer, the experience facing black troops during the war renewed his commitment to the values of the antebellum world, “which had given birth and meaning to his nationalistic beliefs.” The reflections of all three men suggest that Confederates identified closely with one another, their communities, and the Confederate nation. The experience of fighting black soldiers for the first time served to remind Lee’s men of exactly what was at stake in the war—nothing less than an overturning of the racial hierarchy of their antebellum world.45

Newspapers published in the days after the battle echoed the enthusiasm of the men in Lee’s army; editors used the occasion to remind their readers of the sacrifices being made in the trenches of Petersburg and went to great lengths to encourage their readers to remain optimistic and supportive of military efforts in hopes that further victories might lead to a Lincoln defeat in November. Inevitably, newspaper accounts of the battle referenced the presence of USCTs in a way that reinforced the themes already present in the letters and diaries of the soldiers. Most accounts used the widely reported screams of “No quarter!” to justify the response of Confederate soldiers both on the battlefield and in the immediate aftermath. An editorial in a Petersburg newspaper noted the war cry, concluding, “Our brave boys took them at their word and gave them what they had so loudly called for—‘no quarter.’ ”46

The Richmond Times included a great deal of commentary that referenced the presence of black soldiers in the battle both to warn its readers of possible dangers and as a means to maintain support for the war effort. Readers on the home front were made aware of the dangers that black soldiers represented and, by extension, the dangers posed by their own slaves. “Negroes, stimulated by whiskey, may possibly fight well so long so they fight successfully,” continued the report, “but with the first good whipping, their courage, like that of Bob Acres, oozes out at their fingers’ ends.” The attempt to deny black manhood by assuming they had to be “stimulated by whiskey” to fight reinforced stereotypes, while the reference to “whipping” took on a dual meaning between the battlefield and home front as a way to maintain racial control. In addition, the North’s use of black troops allowed the newspaper to draw a sharp distinction between “heartless Yankees” who would stoop to a “barbarous device for adding horrors to the war waged against the South” and “Robert E. Lee, the soldier without reproach, and the Christian gentleman without stain and without dishonor.” Emphasizing Lee’s unblemished moral character highlighted his role as the Confederacy’s best hope for independence even as he served as a model for the rest of the white South to emulate as the enemy took the ominous step of introducing black troops.47

The Richmond Examiner not only acknowledged the execution of black Union soldiers but went a step further and encouraged Mahone to continue the practice in the future: “We beg him [Mahone], hereafter, when negroes are sent forward to murder the wounded, and come shouting ‘no quarter,’ shut your eyes, General, strengthen your stomach with a little brandy and water, and let the work, which God has entrusted to you and your brave men, go forward to its full completion; that is, until every negro has been slaughtered.—Make every salient you are called upon to defend, a Fort Pillow; butcher every negro that Grant sends against your brave troops, and permit them not to soil their hands with the capture of a single hero.”48

Newspapers portrayed Lee’s men as the only obstacle preventing the slaughter of innocent civilians at the hands of uncontrollable former slaves who had been duped into fighting their previous masters. The Richmond Examiner editorial acknowledged the emotional difficulty attached to such behavior, since under normal circumstances blacks should be treated according to the paternal instincts that white Southerners claimed to exercise in the management of their slaves. In the wake of the Crater, however, it was necessary for Lee and his men to stand firm in preventing Nat Turner writ large.

The use of USCTs at the Crater and elsewhere signaled a dramatic shift in the war aims of the United States: from the preservation of the Union in 1861 to a policy that began the process of emancipation and the integration of black Americans more fully into the civic circle. For the men who fought the battle, their initial reactions not only reflected their respective positions on this policy but also anticipated future promises as well as fears. White Southerners, both in the ranks and on the home front, confronted the manifestation of their worst fears in armed black men who, in aiding the Union cause, worked toward the destruction of the Confederacy as well as a way of life built around slavery. On the other hand, while white Union soldiers may have accepted the necessity of abolishing slavery on moral grounds and as a military necessity, their assessment of the performance of their fellow black soldiers suggests that entrenched racial perceptions would continue to influence their judgments. As a unit, the USCTs suffered the highest percentage of casualties of any division that participated in the battle. They also received a disproportionate share of the blame for the defeat from their white comrades and faced unspeakable violence at the hands of their enemy. Nonetheless, black Union soldiers remained fixed on ultimate victory for the nation and embraced the hope that it would lead to the end of slavery and greater civic inclusiveness.