LOOKING FOR A HOME

THE NUMBER OF MUSICIANS in Austin grew exponentially following the rise of Bob Dylan, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones—the international pop music explosion of the 1960s. The Austin scene was derivative in many ways. As happened elsewhere, musicians in the know positioned themselves along an ideological divide between acoustic folk and rock and roll. That line narrowed and blurred as soon as Dylan plugged his guitar into an amp and bawled out, “Naw, naw, naw, it ain’t me, babe.” Country music fell even more out of fashion, the property of hayseeds with mud and manure on their boots. But every guitar player had a hometown somewhere. Austin’s folk and rock scenes in the sixties followed the lead of those in Greenwich Village and Haight Ashbury. They were harbingers, and they shaped and informed Texas music for many years to come.

On music nights Threadgill’s was packed like a sardine can, and competition for the mike was spirited. The easiest route for an aspiring Austin musician was to lend his or her talent to the rock copy bands that played for fraternity and sorority dances. It was a good way to learn music, and the demand for those bands subsided only during summer or semester breaks, and many accomplished Austin musicians paid their dues in that way. But mooning—dropping your trousers for the titillation and shock value of showing off your bare ass—was a fad among the Greeks, and the alligator was the latest rage on the dance floor: boys flopped on their bellies at the feet of their dates and flung their arms and legs around to recycled hits of Wilson Pickett or the Animals. If musicians disdained that atmosphere, the alternative venues were limited. There was the UT student union—where Janis Joplin and later Boz Scaggs briefly held sway—and a variety of small clubs. But Austin did have lots of sunshine and an agreeable city parks department. In the warm months there was music aplenty on the weekends—folk concerts along Town Lake and rock concerts in a little park downtown.

An Austin FM radio station operator and road-racing enthusiast named Rod Kennedy staged the first Zilker Park folk festival in 1965. The lineup included Tom Paxton and a UT folklorist of national repute named Roger Abrahams. Kennedy was enthused enough about the success of his outdoor concerts to open in the capitol area a new club called the Chequered Flag; it was next door to his Texas Speed Museum. Showcased were racing cars that Kennedy hoped would lure a few dollars from the wallets of tourists headed south in 1967 toward the San Antonio Hemisfair. Fewer tourists than expected made the trip to the Hemisfair, and few indeed were tempted to stop over in Austin to see a Birdcage Maserati and experimental Smith Chevy. The decor of the Chequered Flag was that of a fifties coffee house, and at first it was chiefly a hangout for Kennedy’s rally-racing cronies, but the music was lively. He even brought in some jazz acts. Kennedy’s partners, folksingers Allen Damron and Segal Fry, played the first bill. A native Austin folksinger of international reputation, Carolyn Hester, stopped by on occasion to help out, and Kennedy booked acts as diverse as blues singer Mance Lipscomb and New York country boy Ramblin’ Jack Elliott. But the most significant headliners at the Flag were Townes Van Zandt and Jerry Jeff Walker.

Van Zandt was a Fort Worth rich kid who was enthralled by the style and myth of Woody Guthrie. In his Austin days Van Zandt lived in a ramshackle trailer park tucked away in brush of the Clarksville neighborhood west of the Capitol and downtown. Chickens stepped and pecked around junked cars, and neighbors in this traditionally black section of town told stories of parents who had been slaves. But the lore of hoboes and the road pulled at him, and he spent much of his life as a vagabond, writing songs like “Pancho and Lefty”—perhaps the best exploration in American music of the mystique of gringos coming to grief in Mexico—and with earnest deliberation he set about drinking himself to death. His many admirers would be haunted by the federale’s line in his best-known song: “We only let him slip away out of kindness, I suppose.”

Like Elliott, Walker was an itinerant New Yorker. He seemed to aspire to the same calling as Van Zandt. As a youngster Walker had spent the night in a New Orleans drunk tank once and met a minstrel dancer who inspired his classic “Mr. Bojangles.” Someone asked Walker once if he was scared, for he was barely more than a boy. “No, because I’d just been there once,” he reportedly quipped. “You get scared when there’s a pattern.” Walker reveled in the role of the down-and-out musician—he had a voice then that was as clear as a bell, and a temperament erratic as hell. Houston had a number of thriving folk clubs. Walker would sing there, then hitch a ride to Austin. At the Flag he was often surly, often drunk, and during summer gigs he ordered the management to turn off the air conditioning so the crowd could hear his songs. But he quickly became the club favorite. Though he looked the part of a folk musician, standing in front of the mike alone with his guitar, his lyrics balanced humor and sensuality with some inner torment, and an undercurrent in his music fairly begged for bass and drum accompaniment. He sounded almost country.

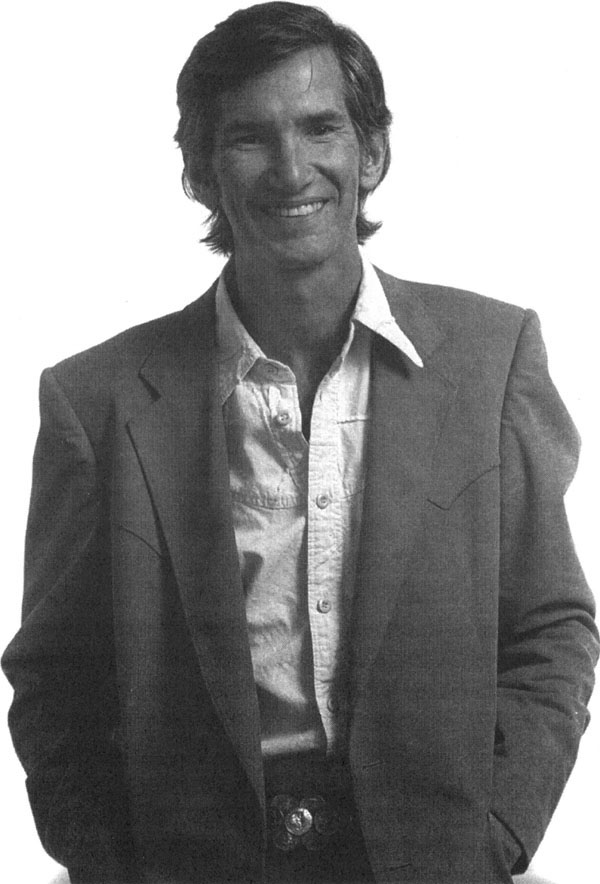

TOWNES VAN ZANDT

Texas Dylan Thomas. Townes Van Zandt was perhaps the most poetic songwriter who came through Austin. His lyrics balanced a bleak view of the human condition with graceful phrasing. 1983.

In 1969 Kennedy was optimistic enough to stage a concert in the municipal auditorium featuring Walker, Hester, Jimmy Driftwood, and Gordon Lightfoot, but the concert lost five thousand dollars. And the Chequered Flag was losing money. Kennedy and his partners tried everything they could to keep the club afloat—discouraging tips in favor of a fifteen percent gratuities fee that never reached the pockets of waitresses who were working for a dollar-fifty an hour and free soda pop. “There were some really magical moments at the Flag,” Kennedy said, “but somehow it managed to lose fifty dollars a day no matter what we did.” Finally Kennedy sold out to Fry and Damron, but they had even less money to lose, and the Flag soon turned into a rock-and-roll joint with a plastic flashing dance floor. It was an unfortunate death, but Kennedy and several of his favorite performers were by no means finished.

THE ROCK AND ROLLERS who got their start in the free concerts in the downtown park traveled an equally frustrating and eventful path. The first Austin rock band that met with success in the sixties revolved around a young man with curly hair and a cherubic expression named Roky Erickson. The 13th Floor Elevators were easier on the ears of their listeners than most psychedelic bands because they restrained their guitars in deference to the adolescent tenor of Erickson, but while his consciousness may have been heightened by the substances he ingested, his lyrics were a whirlpool of philosophical confusion apparently foaming with Karl Marx, the Rig Veda, Bertrand Russell, and Bob Dylan. However, the Elevators were the hottest band in Texas during the mid-sixties. When an Austin bar called the New Orleans Club abandoned Dixieland in favor of Erickson’s crew, crowds approaching a thousand started showing up, and an AM pop station mobilized its remote broadcast unit. Erickson was audacious in his drug advocacy during those broadcasts, and later he would pay for it, but for the moment he was riding high.

Another band of large potential and following was the Conqueroo, whose name derived from an old Howlin’ Wolf lyric. Powell St. John helped form the group, but then he went off to San Francisco, and the driving forces of the band became Ed Guinn, a large black bass player of advantaged Fort Worth origin, and a skinny Austin kid named Bob Brown who started writing songs at the age of fourteen and became the child wonder of the student union set. It was the first time most of the musicians had ever picked up an electronic instrument, and for a while the Conqueroo was convincingly awful, but Guinn and Brown provided good original material, and soon the Conqueroo had a reputation as one of the best white rhythm-and-blues bands in the state.

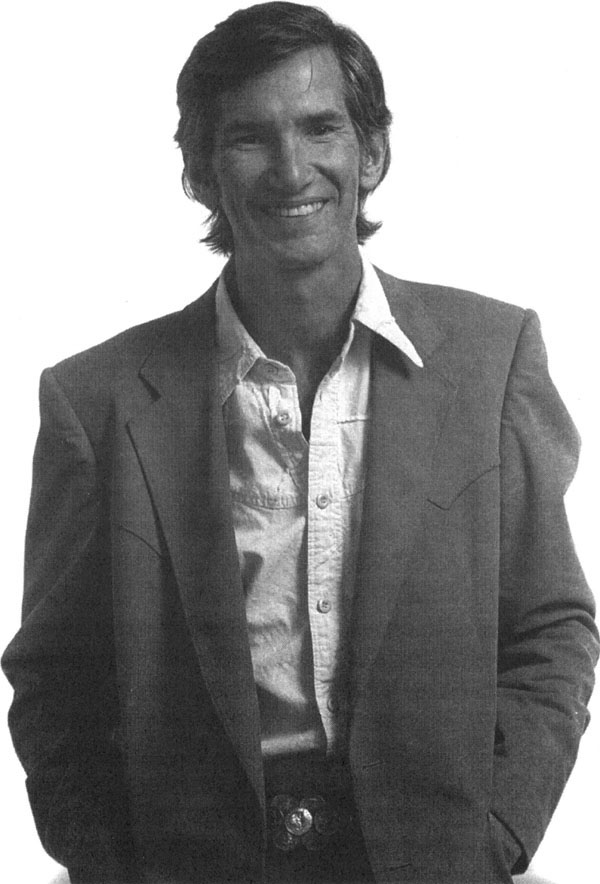

ROKY ERICKSON

Visionary Roky Erickson, here wandering the grounds of a west Austin party, was a fearless, troubled genius who helped invent psychedelic music. 1972.

But demand in Austin for white rhythm-and-blues bands was not that great, and the Conqueroo wound up playing two nights a week for a year in a little bar on the predominantly black east side called the IL Club. Guinn conned the aging owner of the establishment, Ira Littlefield, into an arrangement that, according to Brown, succeeded in running off most of Littlefield’s regular clientele. “It was the kind of place where older black people gathered in the afternoons to play dominoes. But here a bunch of cracker hippies marches down and starts playing so loud that food is flying off forks all over the neighborhood.” However, the older patrons were replaced by white friends of the band, silently critical black musicians, and other young blacks who did their best to make out with the white girls. Everything proceeded smoothly for several months, but then one night the band members and several blacks were discussing the automotive woes of one of the bar patrons. The patron outlined his plans for repair, and the Conqueroo’s articulate sound technician, Sandy Lockett, said that was a niggardly way to go about it. One of the blacks interpreted that as a racial slur, and despite the peacemaking efforts of Guinn, a brawl ensued that left a couple of Conqueroo members in need of surgery and ended only when a black’s pistol went off in his pocket. The police arrived, surveyed the damage, and asked Littlefield what those white boys were doing there anyway. Littlefield said he’d never seen them before.

Lockett was an upper-middle-class youth whose head had been turned around by the collegiate experience in Austin. In 1964 he started working sound for the Elevators and later managed them on the road, but he had even closer ties with the Conqueroo. He believed his friends’ music deserved a hearing, and he also knew it was going to die if they didn’t get one soon. When a group of friends started talking about opening a rock-and-roll club to serve their musician friends’ interests, and another friend stepped forward with enough money to make it feasible, Lockett pitched himself and his money in, and in 1967 they leased some commercial footage in downtown Austin. It was on Congress Avenue, with a broad, straight view toward the Capitol, but the downtown area emptied after nightfall in those days, and for while the activity went unnoticed. The rock and rollers provided their own labor and in five weeks built a club called the Vulcan Gas Company that would gain a national reputation and scandalize the Austin establishment.

The seating inside the Vulcan consisted of benches nailed to the floor, and plumbing pipes stood out from the walls. There was no beer. If a club had a beer or liquor license it could take some of the risk from booking entertainment, for two or three drunks could make up for five unsold music tickets. A club that lived solely by the gate was a precarious enterprise. It operated on the margin above the expenses paid the band, and if no one was interested in hearing that band, there was no money. But the Vulcan had a frantic light show blinking on all walls, a patient landlord, a lot of energy, and the Elevators and the Conqueroo.

The Vulcan was a wild, wild place by Texas standards, frequented by a few blacks who stopped by occasionally for some jive, sun-shaded Airmen trying to be cool, and everybody in Austin who wanted to be a hippie. The managers booked the best talent they could afford, which limited them to their house bands, the Elevators and Conqueroo, and black Texas blues singers—Mance Lipscomb, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Big Joe Williams. “As everybody knows,” Lockett said, “Texas blues singers have had their asses systematically kicked for thirty years. I grew up in Houston, and when us nice little rich kids decided to have ourselves a low-down nasty party, and got tired of our Ray Charles records, we’d go hire Lightnin’ Hopkins. His standard fee was twenty dollars and two fifths of gin. It wasn’t quite that bad when we brought him to the Vulcan, but it wasn’t much better.”

The Vulcan was primarily a rock-and-roll joint, though, which made it a threatening presence. The normally deserted downtown area had begun to swarm at night with hippies who were smoking and selling marijuana. One couple used to park their van in front of the Vulcan, turn on the portable television, and open their doors for business. Newspaper columnists and civic leaders began to snipe at the Vulcan, but artists with growing national reputations like Steve Miller raved about the Austin audiences, and the management held on.

The Elevators and Conqueroo soon shone with the aura of Texas holy men. The Elevators were releasing albums through a group of Houston businessmen who called themselves International Artists, the band was a favorite at the Avalon Ballroom in San Francisco, and Roky Erickson was an inspiration to dope-smokers. The police busted him, and he responded by insisting publicly that he had done nothing wrong. Eventually he was a kind of local Donovan, striding through a room spewing wisdom while a fellow band member, sure in the belief he was Moses, climbed in a chair and started preaching a sermon.

The Conqueroo were a little more down to earth, though not much. In the early days they lived in an apartment called the Ghetto, where they met the novelist and reigning cultural hero, Billy Lee Brammer, who gladly watched as his circle of friends changed from LBJ politicians and journalists to twenty-year-old hippies and musicians. Brammer got a kick out of Guinn and thought Brown had considerable talent as a writer, and after signing on to write public relations for the Hemisfair in San Antonio, Brammer talked his landlord into renting the upper floor of a turreted Victorian mansion to the Conqueroo. The mansion on West Avenue—which would later be restored as a site for Junior League weddings—quickly became a hippie crash pad. A couple of dozen people often slept on the floors at night, and the object of the game in the daytime was to take as many drugs as physiology and peer pressure would allow.

The Conqueroo cult had a brief encounter with the psychedelic big-time. Ken Kesey was a friend of Larry McMurtry, and when the Merry Pranksters took to the road for one of their wild swings through the country they stopped in Houston to see the novelist, who steered them to the San Antonio apartment of Brammer, where they attracted throngs of watchful cops. After a couple of days Brammer gave them directions to the mansion in Austin. The Pranksters descended in grease paint and propeller caps, nursed their young on curbs in five o’clock traffic, and stayed for a week. A few of the more impressionable Austinites gathered in awe to watch the lordly Kesey piss, but what the Pranksters had found was a group of young Texans already too stoned to pay them much heed.

Unfortunately, the ascendancy of both the Elevators and Conqueroo was short-lived. The Elevators got very little from their association with International Artists, gained a reputation in San Francisco as a band that failed to show up, and fell into exhausted disarray. Then one night Erickson got busted one time too many. The Texas judicial system couldn’t seem to communicate with the fallen rock star, so it sent him to a state hospital for the criminally insane. It was nearly three years before Erickson could win his freedom. During his protracted convalescence he tried to get a hold on things by turning to Christianity. He began to sign his letters Rev. Roky Erickson, and he wrote a book of poetry called Openers that was published by financially endowed friends on the outside. The book contained the standard thee’s and thou’s, stoned images, and wordplay of most Jesus-freak verse—with a little more rock-lyric vividness and brevity—but scattered throughout the thin book were agonized cries of pain. Erickson was subsequently diagnosed as a victim of schizophrenia, and he roved that wilderness for many years. One of his poems was titled “Ye Are Not Crazy Man.”

The Conqueroo endured a more common demise. Convinced that they had gone as far as they could in Texas, they made the rock pilgrimage to San Francisco, where the drummer promptly freaked out and fled back to Texas, and the others were not so sure they liked what they saw. “San Francisco started dying about six months before we got there,” Brown said. “The scene was really starting to degenerate. Haight Street smelled like piss, and a lot of little stores were closing down. All the people we thought were running around with flowers in their hair were now lying around with needles stuck in their necks.” Compounding the hassle for Brown were the lack of privacy, a murder rate of two per month in the neighborhood, regular burglaries of musicians’ equipment, and bereted Black Panthers who scared the living daylights out of him. Brown was not yet twenty-one. Worst of all, nobody listened to their music. “We went out there and played in the park with Santana and Big Brother, and I think we played better than any of them, but people just slipped right over us. ‘We want the guys from California, bring on Big Brother.’ And, man, Big Brother was horrible. Those guys knew two or three chords apiece and couldn’t even play those.”

One of the last straws was when a writer from Rolling Stone came around to interview Brown. The writer asked about music in Texas, and wanting to spread the good fortune around, Brown told him about a white, very blond blues guitarist from Houston named Johnny Winter. He was rumored to be an albino. The writer’s eyes flashed white-white, black-black, and shortly afterward Winter headlined the feature on Texas music. Very shortly afterward, Winter signed what was then a record six-figure deal with a major label. The rock writer neglected to mention the Conqueroo.

Weary and discouraged, the band broke up. Guinn became a long-haul truck driver, but Brown and St. John formed another group called the Angel Band, whose name derived from a gospel lyric. Even that led to more indignity. The Hell’s Angels came around one night and wanted to know what right the band had to that name, and the musicians had to beg forgiveness. Finally Brown drifted back to Austin and opened an antique shop, bitter at twenty-three.

WHILE THOSE PLAYERS were falling out, others were drifting in. The musicians drawn to Austin over the years were informed not just by existing forms and commercial genres. They came from locales and regions, and the infusion and intertwining of their roots refined and enriched an Austin sound that was different from San Francisco’s or Boulder’s or Tuscaloosa’s. On the heels of the English Invasion, the hottest Texas rockers were from San Antonio. Augie Meyers came from German and Polish stock. Stricken as a child with polio, Meyers didn’t walk until he was ten—one doctor wanted to amputate his withered left leg. In a little farming community east of San Antonio, his grandfather urged neighbors to bring him all the mud dauber nests they could find, and he made poultices from the wasps’ adobe for the boy’s leg and arm. Meyers realized what he wanted to do with his life when he saw some Mexican boys playing garage-band rock with the first electric guitars he’d ever seen. “My daddy spoke great Spanish, and he loved Mexican music. He said, ‘Boy, get you an accordion and play that kind of music, and you’ll go somewhere.’ I’d look at him and say, ‘Come on, Daddy, I wanta play like Little Richard or Jimmy Reed!’”

In 1951, when he was eleven, Meyers met Doug Sahm, the son of a civil-service worker at Kelly Air Force Base. Sahm loved baseball, and Meyers, who was sacking groceries at his mother’s neighborhood store, would break into bubblegum packs to get him the cards he wanted. Sahm longed for music, too. At night he would sneak across the golf course of an eastside country club and try to get to a window so he could see the great T-Bone Walker. One night the doorkeeper was touched by the skinny little boy and let him sit beside the band on the stage. Sahm had a number of accomplished mentors and a reputation as a child prodigy western-swing steel guitar player. But an electric lead guitar was the instrument that came alive in his hands, and like his friend and rival Augie, he fronted teen bands that might get to play a hop at an Arthur Murray dance studio. Meyers bought the first Vox organ, he claimed, in the United States for $265 because he liked the alternating black and white keys. Although he was a fine rhythm guitar player as well, his stabbing, hypnotic style on the organ drove the music like a overworked heart. Sahm was a flashy singer. He leaped and pranced and yelped, one part adrenaline, one part soul. In 1964 their bands were the second and third acts for a San Antonio concert by the Dave Clark Five. The storied Gulf coast producer Huey Meaux, whose acts had included Fats Domino and T-Bone Walker, listened and then cornered them: “You both got long hair—do you know each other? You gotta get a band together.” In Beatle boots and tight pants, they were off and roaring as the Sir Douglas Quintet. Meaux claimed they were English. He got them a date on one of the early rock music TV shows, and told them just to sing, not talk. Two of their players were Hispanic, and the accents would never do. It was a shrewd and shameless knockoff of the Liverpool sound—yet their own roots in San Antonio’s ethnic mix came through. In time Meyers did learn to play the accordion. “Ooom pah pah came first,” he said of the underpinnings of their first hit. “‘She’s about a Mover,’ that’s just a polka with a rock-and-roll beat.” The song came about one night when they were playing and a young man and woman were putting on a dance show in front of the stage. She was throwing a long skirt up over her head, and Sahm turned to the others and said, “She’s about a mover, isn’t she?”

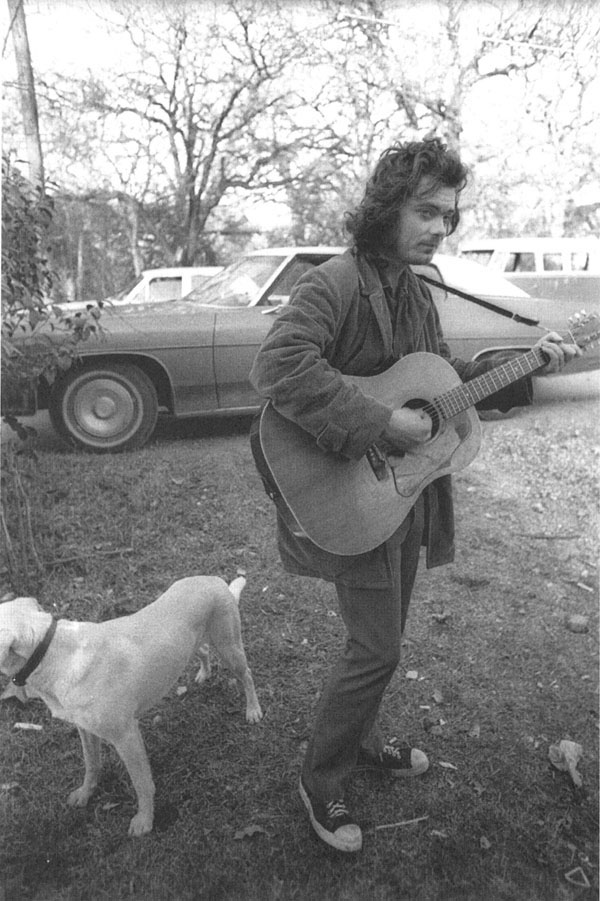

AUGIE MEYERS

Stalwart. San Antonio native Augie Meyers was sometimes Doug Sahm’s rival, sometimes a sideman, and, since their boyhoods, Sahm’s devoted best friend. Meyers brought an uncommon blend of ethnic styles and influences to Texas rock and roll. 1979.

They had a record in the top ten and were doing everything they could to promote it. Meyers said, “One time Huey called us and said he had us on with the Monkees. We had to get up early in the morning in North Dakota and fly to Minnesota, and then Chicago, and then to Ohio and Virginia and Philadelphia, changing planes every stop. We got to Maryland at seven in the evening and this guy says, ‘You’re on next. You’ve got four songs.’” But in 1965 the players got busted in Corpus Christi for two joints. Sahm and others were arrested at the airport, and Meyers was hauled out of his car with a shotgun to his head while his young family watched. Juries and judges in Texas were routinely imposing sentences in scores of years for possession of marijuana. The Quintet’s probation was not gotten cheaply, and the terms were not permissive. They couldn’t leave the state, a distinct disadvantage for a rock band trying to promote records. Kids in Texas packed halls to see the homegrown longhairs, but as Meyers put it, “Damn, there’s some mean towns out there.”

As soon they served out their terms in 1967 they fled for California. The British conceit and name fell away and would be periodically revived, but the sound had always been Sahm’s and Meyers’, and unlike many rockers drawn to the Haight, they knew the difference between music and acid. Their album Mendocino was one of the anthems of the period; Sahm made the coveted cover of Rolling Stone, posing with his young son Shawn. “California was real good for longhairs until Charles Manson committed those murders,” Meyers said. “After that we weren’t so popular.” He didn’t like a 1971 earthquake either, and that year he and his family moved back his parents’ farmhouse at Bulverde, in the hills north of San Antonio. Sahm and his family soon followed. “A lot of musicians started coming back to Texas from San Francisco,” said Meyers. “That’s when Austin music exploded.”

DOUG SAHM

It’s Only Rock and Roll. This shot from a Houston performance evokes the frenetic style and energy that burst from Doug Sahm. 1973.

One such player was a lead guitarist named Jesse Taylor. His dad had been a weekend country musician around Lubbock. The hangout in town was a drive-in called the Hi-D-Ho, and Taylor remembered his dad pointing out a skinny guy with glasses driving a pink Cadillac convertible; four girls were hanging all over him. “Look, there’s Buddy,” said Taylor’s dad. It was Buddy Holly, Lubbock’s answer to Elvis. Holly’s life was so short, his stardom so brief, that few west Texas musicians influenced by him ever got to see him play, but his songs and hiccup-yodel phrasings made him one of the giants of rock and roll. Jesse Taylor begged his mother to buy him a fifty-dollar guitar, and he noticed that the skill came to him faster than his friends. Like Sahm and Meyers in San Antonio, he realized at once that playing music was all he ever wanted to do, and like them he dropped out of high school and started chasing the dream. He met Jimmie Dale Gilmore, whose dad was an accomplished musician, and Joe Ely, whose dad owned a clothing store. Gilmore was singing folk music then; Ely was a baby Buddy Holly. “We called our bands ‘combos,’” said Taylor, laughing. “We were friends and rivals. We all had to have a combo.” A busy railroad ran right through the middle of town, and they started hopping freights across the desert to California and the ocean, living in Venice Beach apartments until their money ran out. “We couldn’t get in a club,” Taylor said, “much less play in one.” But back in Lubbock their T-Nichol House Band became the hottest act in town. Named for a local beatnik who inspired them, the band would jump in successive songs from Ray Price’s “Crazy Arms” to covers of B. B. King and Chuck Berry—country and blues and rock. They were joined by John Reed, a guitarist from Amarillo, and in time they met Butch Hancock, who awed them with his songwriting. Many other musicians of note came out of the windblown cotton town, but that one group of friends would play an outsized role in defining Austin music.

In 1967 a Lubbock native, University of Texas student, and singer named Angela Strehli asked Taylor if he wanted to come to Austin and play behind her. “This gorgeous hippie chick—well, yeah. It wasn’t hard to decide.” They played at the Vulcan Gas Company but more reliably at the small clubs on the east side—the IL Club and Ernie’s Chicken Shack and the Night Owl. Young blacks were in a militant political uproar, and they were into Motown and soul. To them the blues was Jim Crow music. But the old-timers were interested in hearing that white girl wail. Taylor by then had a wife and small daughter, but before he could settle down he had to get his fill of San Francisco. Their housemates included Wally Stofer, harmonica player of the disbanded Conqueroo. Taylor played in a band that fronted for Doug Sahm at the Avalon Ballroom. They were friends with the band of Johnny Winter, the singer from Texas who had just signed a big contract and been the subject of a feature in Life magazine. The bass player was Tommy Shannon—two decades later the mainstay of Stevie Ray Vaughan’s band. It was a scene of enormous talent and a heady time. “But after eight or nine months we couldn’t get much happening,” said Taylor. “We started thinking about Austin and all those gigs. A lot of people started heading back to Texas.”

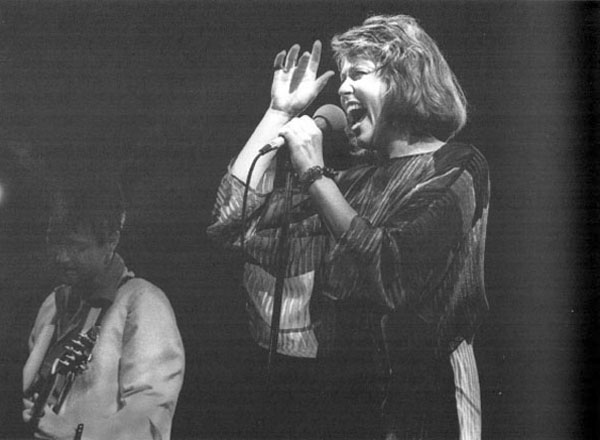

ANGELA STREHLI

Texas Soul. After growing up in Lubbock, Angela Strehli arrived in Austin knowing exactly what she liked to hear and sing—rhythm and blues. Her voice helped carry the blues pipeline out of Austin. 1980.

But in Austin the rock emporium was in trouble. “It was a giant maw of a goddamn furnace that you had to keep stoked with money,” Sandy Lockett said. The Vulcan’s managers had grown tired, in part because they had been doing it too long, but also the times were changing, and the Vulcan crowds were changing with them. “We had a bouncer who was five-six, a master of tact and discernment,” Lockett said, “which was all right, because in the first year of the Vulcan’s existence it was difficult to tell whether we had a regular money-making gig or a private party. In the last year it was difficult to tell whether we had a rock-and-roll club or a wrestling match. It got a little rough.” Tired of the strain, the Vulcan managers started looking for someone to keep the club going, but none of the new managers worked out, and the club died in 1970.

NOT LONG AFTERWARD, the Kerrville Folk Festival, initiated in 1972, became a high point of Texas’s musical year. A sound man who had worked the Atlanta Pop Festival and was on the team at the Concert for Bangladesh engineered the mix for festival founder Rod Kennedy free of charge, and the spirit of high cooperation extended to the performers. They hopped onstage and lent their talents to their friends in the spotlight; in 1973 Willie Nelson refused to press charges when a Kerrville woman stole his wife’s purse. The Kerrville police couldn’t understand it. All but one of the performers was able to obtain releases from their recording companies to appear on limited-edition Kerrville Folk Festival albums, which became collectors’ items.

When I talked to Kennedy he was preparing for the expanded 1974 festival. He had added bluegrass and ragtime festivals on other holiday weekends, but the feature event remained the folk festival, and it had already outgrown the small Kerrville auditorium. In 1973 Kennedy had to turn away scores of families at the door. So he purchased several acres of land outside Kerrville and started clearing an outdoor arena that would have an eventual capacity of nearly five thousand. He was even so confident of the festivals’ continued success that he sold his home in Austin and built a cabin on the property. “I’ve just finished my first hundred hours of chain-sawing,” he said cheerfully. “And I’ve traded in my racing car for a four-wheel drive jeep. Which is good.”

But his primary worry that day was not preparation of the site, but the task of convincing the people of Kerr County that his festivals were not about to ruin the Hill Country. The Texas establishment had became extremely wary of outdoor music festivals after a group of promoters sneaked Janis Joplin, Chicago, Santana, Led Zeppelin, Eric Clapton, Herbie Mann, and several other big-name acts into an automotive speedway barely outside the Dallas city limits in 1969. A Dallas Morning News editorial regretted that the paper could not welcome young people who refused to work, cohabited in flagrant infidelity, and defied the state’s narcotics statutes. Whatever happened to the responsible young people of yesteryear? the editorial writer wondered. Well, they still existed, and that Saturday they would be at home mowing their parents’ lawns, while “the lewd and loose [were] swinging in Lewisville.” More important to Rod Kennedy, the Texas legislature rushed through a statute that made an outdoor music concert an extremely difficult undertaking, for the promoters had to have the blessing of the local county commissioners every step of the way.

“There’s a great deal of local trepidation about what we’re doing up there,” Kennedy said. “We’re keeping up a continuing, low-pressure publicity campaign about our moving to Kerrville, about the way our festivals bring young and old people together, about the age-old tradition of festivals in this country. To the uninitiated, the word ‘festival’ means rock, pot, bottle-throwing, filth. Which is something we’re campaigning against.”

ROCK AND ROLLERS had no place at the Kerrville Folk Festival, and times had quickly gotten hard for them. The new Armadillo World Headquarters was thriving, but it could only book so many acts, and the blues rockers grumbled that all the gigs were going to the country rockers suddenly swarming in Austin. The celebrated rebel of all the rebel joints was the Soap Creek Saloon, which had multiple locations but saw its best days at the end of a severely potholed dirt road in a Westlake Hills cedar brake. It seemed so far out in the sticks no one could possibly object. But the suburb’s upper-middle-class school district built a new junior high within a mile of the club and then started applying pressure on the city council to revoke the club’s liquor license.

“The Armadillo’s focus was on booking major touring acts,” said one of Soap Creek’s owners, Carlyne Majer. “We wanted to provide a home to local artists, and our shows encompassed blues and country and roots rock.” The hero of the rock and rollers was Doug Sahm. After he returned to Texas and the Quintet broke up, he moved into a big house on a hillside overlooking Soap Creek. He lay low for a while, then in 1973 jumped back in the fray with a country-rock-blues album and a showy array of sidemen who included Bob Dylan and Dr. John. Though he wore a cowboy hat and liked to sit in with Willie Nelson, Sahm was ambivalent about Armadillo World Headquarters and told a Rolling Stone correspondent, “People are tired of this cosmic cowboy shit. They’re ready to rock and roll.”

Sahm soon found, though, that he got more local ink if he appeared to be a part of the prevailing scene, and he began to show up at the country rockers’ concerts. He even talked about organizing a cosmic cowboy tour. A typical Sahm performance started with the Charley Pride classic, “(Is Anybody Going to) San Antone,” jumped through conjunto and Cajun and rhythm and blues, ending with a hilarious, dead-on take on Mick Jagger singing “Honky-Tonk Woman.” Sahm was all over the stage—plunking a piano with one hand, jamming one-on-one with the drummer, twirling a sombrero on the end of his guitar. His second album was aptly called Texas Tornado.

Those performances left him soaked with sweat and wired tight. Sahm could be a very difficult person. “Look, look here,” he was haggling a hotel clerk in Austin one night, “I want you to place that call to San Antonio.”

“Goddamn it, man,” the clerk finally thundered. “I am busy!”

Sahm backed off a step, trembling. “I-I worked hard tonight,” he announced, “and I was damn good.” Then he flinched and looked around the room for eavesdroppers. “Listen, you make that phone call,” he said to the clerk, and then took a woman friend up the stairs toward his room, muttering to himself.

Sahm encouraged Austin rockers to hang on—the pendulum would inevitably swing back from country toward rock. One of the young performers he encouraged was Bob Brown, who along with Ed Guinn was trying to revive the Conqueroo. But Brown seemed to know the odds were long. Looking back on the days in San Francisco, Brown said, “We didn’t feel like we could play out there unless we were carried in on stretchers. That was the thing; music didn’t sound good if it was just good music. It was supposed to blow your mind, mesmerize or milk you.

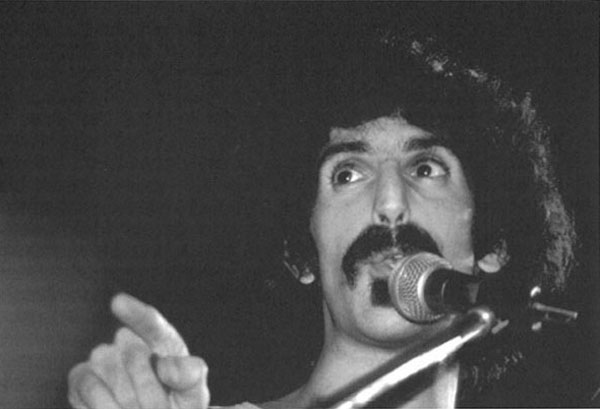

FRANK ZAPPA

Just another Band from L.A. This rock icon’s performance at the Armadillo certified its standing as a venue of national importance; loving its crowds, Zappa continued to come back. 1972.

“We did that a few times, and we’d look out and there’d be people wallowing on the floor, writhing around, eyeballs rolling back in their heads. And that’s what we wanted. I suppose a lot of young people took all those drugs because I did, and I really regret it now.”

Brown was no more approving of the Austin scene, though. “The stuff in vogue around here is nice, sweet, boring crap. It stinks, it’s phony. A bunch of funky, loose, spoiled, TV-bred longhairs are now singing songs about wanting to ride the fence in Wyoming, you know, or retire to the cabin on the ranch. They’re full of shit; they don’t know what they’re talking about.

“I walked in the Armadillo the other night, and it was full of guys with the same length hair and cowboy hats and cowboy boots. It’s fine, I guess, I just think it’s immature. But I guess that’s what fads are: people groping to find mutual identity. Of course, if I were playing hillbilly country I’d think things were finally beginning to happen.

“But I don’t know where all the magic is. I’ve been writing country music since I was fourteen, and what would happen to me then is what happens now. You sing a jovial, hah-hah, beer-drinking country tune, and then you sing a very romantic, serious country tune, and the reaction you get is the same. Yee-haw! Country music is whooping and hollering and pouring beer on your head. My experience was that they’d whoop and holler in the middle of a song about your dying grandmother.

“And either consciously or unconsciously,” he said, “the Armadillo is quashing all other forms of music. And that really pisses me off; I feel like I invented those people.”

But Brown also had to be aware the magic hadn’t come back to the Conqueroo. When I caught their act one night at Soap Creek, Brown impressed me with his songwriting, though his attempts to sing black blues were as strained as those of most Anglo tenors. Guinn, who had abandoned his bass in favor of a piano, was also impressive—a mixture of blues, jazz, and Fats Domino. But they were playing with a lightweight bassist, a drummer borrowed for the summer from one of the country rockers, a lead guitarist who had been with the band less than a week, and two female vocalists who seemed determined to steal Brown’s thunder. And the only genuinely interested people in the small crowd seemed to be Sandy Lockett, who still liked to fiddle around with the electronics of music occasionally, and their old patron Billy Lee Brammer, who had just missed a deadline for a magazine article about Texas’ marijuana dealers because his teeth got so bad they required pulling. Lockett bobbed up and down behind the amplifiers, and Brammer grinned encouragement and approval through his new dentures, but Brown and Guinn were pulling dead weight. The best musicians in town had jumped aboard the country bandwagon, and they weren’t about to stand by the roadside with a band like the Conqueroo. The Conqueroo gig limped to a halt, which was what many members of the audience wanted anyway. The real attraction at Soap Creek that night was an after-hours party featuring Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings’s band.