SOMETHING TO DO WITH AGE

IF SOMEONE HAD SET OUT in search of a music nativity in the autumn of 1963, the campus of North Texas State University in Denton might have seemed an unlikely place to look. It was a suitcase college, an intellectual truck stop for those students who didn’t want or couldn’t afford to get too far away from Dallas-Fort Worth, and for those who didn’t quite think they could hack it at larger schools like the University of Texas. Denton was a pleasant but dull little north Texas town on the rolling plains midway between Dallas-Fort Worth and Oklahoma. Several national fraternities and sororities had chapters on campus, but it was thirty miles to the nearest liquor store, coeds had to live in house-mothered dormitories, and the football team was the patsy of the Missouri Valley Conference.

But the university had a reputation as a music school. A jazz program and its lab band found a deep talent pool of young artists, and on week nights in the student union, which was called the Sub, a folk music club gathered that could have been called Threadgill’s North. The faculty sponsor of the club was Stan Alexander, a regular at Threadgill’s during the days of Janis Joplin, when he was a doctoral candidate in English at the University of Texas. When Alexander joined the faculty at North Texas, his zeal for folk music was waning. “The first great wave of folk-pop music had passed,” he would write, “and the Kingston Trio was like an inexhaustible stratum yielding a single fossil form. They went on and on, with the Brothers Three, Four, Five, whatever it was, until they were rich and tired and had used up the folk music collections in the Eastern universities.” But Alexander missed Threadgill’s, so he sat patiently while the students found out about their voices and instruments. It was an audacious, musically directionless gathering of aspiring performers and hangers-on, but five of them were bound for a musical reunion.

Travis Holland was a scrawny, dark-haired man in his mid-twenties, one of those persistent students who had a hard time getting his degree in math because he couldn’t make sense of language. He grew up in the Red River peach orchard country surrounding Charlie, a lost burg near Wichita Falls, spoke with studied pauses and a Texas drawl that made him sound forty years older than he was, and viewed things with wry humor. “Wichita Falls,” he used to say. “That’s a weird place . . . full of . . . suppressed malice.” As a musician he was most comfortable playing rhythm or bass guitar. An eventual president of the music club was a teenager of transient Texas origin named Steve Fromholz. He was sleepy-eyed, sardonic, egocentric, and thoroughly open to experience. All he knew was that college didn’t interest him, and he had a sister who had cut some Sun Records during the days of Elvis Presley. Alexander didn’t think Fromholz had much talent, and neither did Travis Holland, who one night kicked Fromholz’s door open and said, “I’m either gonna have to teach you how to play that banjo or take it away from you.”

At an introspective remove was another freshman named Michael Murphey, a Dallas youth so earnest about his Baptist religion that he decided if he was going to make a preacher, he ought to learn classical Greek so he could read the earliest texts. Murphey got interested in the classical poets instead, and when he joined the club he was already a promising guitar player and an aspiring vocal cross between Chad Mitchell and Bob Dylan. Alexander turned Murphey on to the possibilities of country music once it cleared the city limits of Nashville, and the star pupil itched with impatience when the girls with ukuleles and autoharps had the floor. Murphey was already dead serious about making music.

Eddie Wilson was a barrel-chested sophomore philosophy student, a former “mediocre jock, hot-rodder, and general slob” from Austin. His parents had forced piano lessons upon him at an early age, and as a result he refused to play a note, but he thought about music a lot, and he had become acquainted with Alexander during a brief enrollment at the University of Texas. Spencer Perskin was an upper-middle-class Dallas youth who had been studying violin at the feet of an Southern Methodist University virtuoso since junior high. Perskin was also learning to sing and play the guitar and harmonica.

After two years Alexander accepted another teaching position at a small state college called Tarleton State; the folk club dissolved, and its members scattered. Perskin structured a poem in an underground newspaper which, if read conventionally, said something rather tame, but if read horizontally, told the readers to screw themselves. A controversial figure in Denton, Perskin headed south to Austin and put together a group called Shiva’s Headband which became the last cult band at the Vulcan Gas Company. Perskin lent his voice, harmonica, lead guitar, electric fiddle, and electric jug to a conglomerate sound that incorporated blues, country, and jazzy self-indulgence, and attracted a rabid Texas following and a California record contract.

Wilson’s path took him completely away from the music business for a while. He met a pretty girl named Jeannie in a Shakespeare class and married her. He enjoyed his stay in Denton, then after graduation moved deep into south Texas where he coached athletics at a black high school while Jeannie taught in the white school across the road. That didn’t last long, because, according to Wilson: “The white folks fired me for being a nigger-lover, among other things. They said I had a motorcycle image, and what really got on their nerves was that my football team won district and my track team won second in state, and none of my black athletes would sign freedom-of-choice blanks to go to the white high school the next year. They figured I was a stumbling block.”

Wilson moved on to a lobbyist trainee position with the United States Brewers Association. Miserable by early 1970, and for lack of anything better to do, Wilson had decided to go to law school. But then Perskin showed up at his house in Austin one day and stayed six weeks, and abruptly, Wilson was managing Shiva’s Headband. He knew nothing whatsoever about the music business, which was exactly what the distrusting acid-rockers wanted, and Wilson admitted later that his management probably contributed to the band’s premature demise.

Through them, Wilson was thrown into association with the forces behind the Vulcan Gas Company, among them Jim Franklin, a hardcore freak and eccentric from the Galveston-area town of La Marque. He said his life was almost ruined by interest in theater, art, black girls, and drugs. He won first in state in competitive poetry reading. That, “needless to say, was overshadowed by the failure of the football team to win state. That was my first experience with gross mysticism at the football level. The coach called the student body together after the loss and said it was our fault for not supporting the team and afterward broke into tears. He later died of cancer.” Franklin also contributed large paintings of African and Galveston black families to the high school library, which were taken down when the school integrated. After graduation he painted sets and acted in summer stock in Kerrville for awhile, spent a year in New York, then returned to Austin in the mid-sixties, where one night he took his first tab of acid, then went for a walk. Accosted by a police patrolman who asked for some identification, Franklin unzipped his pants and wound up in jail. His parents and attorney convinced the authorities he was a good boy who had simply fallen into bad company, and he returned to Galveston, where he hijacked his father’s pickup and headed for a Bob Dylan concert in Austin, only to run afoul of the law once again. This time they found a lid of marijuana in the glovebox. After that he fell into the hands of a Galveston County doctor, who administered eighteen therapeutic shock treatments.

(At least that was his story. Franklin liked to put people on, a habit that could render everything he said suspect. One week he would swear he was a lineal descendant of Benjamin Franklin and boast that he once modeled for Clearasil commercials, and the next forget he ever said it.)

Franklin was a live-in hanger-on and roustabout in the latter days of the Vulcan, but he also provided some of the graphic arts for the establishment and much of the defiant spirit. “The guy who ran the hardware store across the street sold Charles Whitman his ammunition,” he claimed. “He got all kinds of attention in the national press, and after that his gun business boomed like hell. The first thing he did was slice up and sell the columns of his building, which was really a fine piece of architecture, then he started complaining about us—we were the bad influence on the community.”

Franklin was out of state when the Vulcan finally went under, and when he came back Wilson had leased the abandoned armory in south Austin that became the Armadillo, so Franklin moved his mattress into the new attic. Shortly afterward they were joined by Mike Tolleson. The son of an east Texas lumber dealer, Tolleson had bachelor and law degrees from Southern Methodist University, but he was bitten by the music-business bug at the undergraduate level when he tried to generate a campus radio station, and again at the law-school level when he donated his student-loan check to a demo tape by a Dallas group called the Exotics. Nothing came of the effort, though Monument Records expressed some interest, and Tolleson went off to the University of London to study international law. He found the courses as repetitive of those at SMU, and his interests evolved toward R. D. Laing, the Beatles, and the international legal aspects of the communications industry. He designed a study program at the London School of Economics, but soon ran out of money and signed on as an editorial and research adviser for a Mexican diplomat who was writing a book on international economics. Tolleson watched the growth of Apple Records, met John Lennon, and hung out in an underground arts laboratory for young Britons of artistic interest and intent.

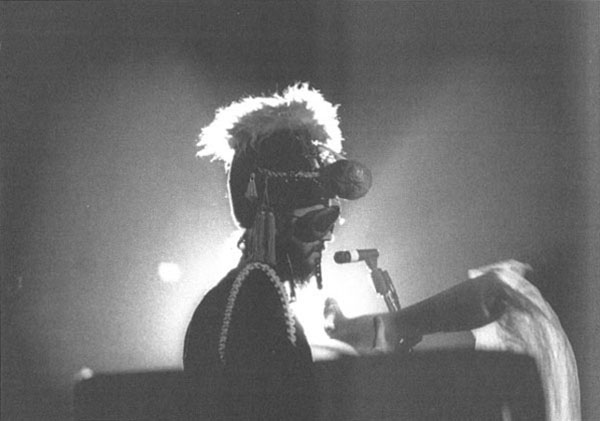

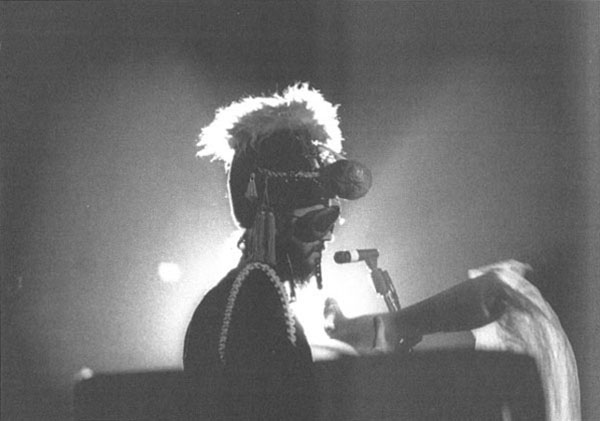

JIM FRANKLIN

Master of Ceremony. Introducing bands (he was costumed here in one typical appearance) and illustrating posters, Jim Franklin lived on the premises of the Armadillo World Headquarters as a defining house artist and enigma. 1973.

When the diplomat’s book was finished, Tolleson fled to Switzerland to recuperate, then decided to return to Texas and open a similar arts laboratory in Dallas. Instead, he again contributed his capital to the Outcasts, an offshoot of the Exotics. Tolleson knew Snuff Garrett, a west Texas disk jockey (and TV celebrity in Wichita Falls) who had moved on to a radio station in Dallas, and then migrated to Los Angeles, where he produced records of Gary Lewis and the Playboys. Later he produced country music. Garrett relayed news of the Outcasts to one of Lewis’s Playboys, Leon Russell. The longhair hit Dallas, listened sagely, and trucked the band off to California. Once again, not much came of it, but one of the younger Outcasts, Marc Benno, stayed on and surfaced during Russell’s Asylum Choir phase.

In August of 1970 Tolleson went to Austin for a weekend, heard about the Armadillo, and left Wilson a job application form. Others were involved in the Armadillo’s inception, and the staff eventually swelled to more than thirty, but Wilson, Franklin, and Tolleson were always the cutting edge of the organization. Wilson was the boss-man, the booming voice out front who talked back when Los Angeles wheeler-dealers shouted at him, who treated musicians fairly, who knew what to say to a curious press. Franklin was the house painter, spiritual guru, and bon vivant onstage. He decorated his room with remarkable clutter, a dusty American flag, a black cat named Charley Pride, a five-foot-eight-inch boa constrictor, and a feathery bird skeleton trapped in a cage. Franklin also developed an onstage routine and designed the costumes for it—a five-foot cowboy hat, a giant Planters Peanut suit, a suit of unconventional armor with an armadillo mask. “Most emcees don’t master any ceremonies,” he said. “They don’t have any ceremony to master. “He also turned his armadillo art into a profitable business. He designed the covers for nationally distributed albums, one of which appeared in the Whitney Museum in New York. His murals started appearing on new storefronts all over Austin, and his T-shirts portraying a nearsighted armadillo humping the state capitol dome eventually sold well on consignment. Tolleson was the quiet, thinking man behind the scenes, a balding man who was always running his hand over his scalp as he charted the next day’s course of action.

But for now there could be no specialization. Though Perskin and Shiva’s Headband called the new club home and infused a healthy portion of their contract bonus into the project, the Armadillo was a mad scramble for survival that demanded all hands everywhere. The staff hammered and nailed a stage together, dragged in some carpet scraps, offered some apple juice and pumpkin bread for refreshments, and opened with three top local bands, but the odds seemed against them. The Vulcan had failed, and it had once been a success. What made these people think they could pull it off? How were they different? Their timing seemed to be all wrong. The summer of 1970 was a hot one in Texas, and a sluggish malaise gripped all sectors of the Austin community. Lyndon Johnson was an ex-president, a series of political scandals called Sharpstown was beginning to surface around the Capitol, the professors were out of town, the everyday people doggedly drove the freeways to work. The malaise even visited the sector seized by the spirit of love. “About the time Armadillo World Headquarters opened,” Wilson recalled, “the subculture here, the alternative culture—the counter-culture, I believe it’s called—was really in a kind of quandary. There was a lot of dissension among people who were in basic philosophical agreement about things social and political. There wasn’t a focal point—and just very little productive energy.

“That summer we started was really a bad one from my point of view. There were just a lot of unhappy, frustrated people all over town. And we didn’t do anything to help it—we gave a lot of people something to bitch about. The Vulcan had been gone for a few months, and we provided the straight people with something to complain about, and we even gave the counter-culture a chance to bellyache, at least the more politically-minded among them. They’d stand back and scrutinize what we were doing and try to decide whether it was politically viable. But we really didn’t have time to participate in those discussions because we were working our asses off.”

A few things were working in the Armadillo’s favor. Its location was much more fortunate than that of the Vulcan. Dammed into Town Lake, the Colorado River bisects Austin, and the southern side of the river was almost a community in itself, historically relegated to the Chicanos and Mexican immigrants and lower-middle-class whites, though it had begun to experience the longhair invasion. The only neighbors the Armadillo customers could bother were young blacks who hung out at the roller rink, a former candidate for county constable who ran a nearby paint and body shop, and a few workers in a Social Security office. If Austin had to have its hippies, establishment feeling seemed to run, at least now they would be out of sight and the downtown area. Like the Vulcan, the Armadillo had an understanding landlord, and a happy-go-lucky clique of Austin writers and artists called Maddog Inc. gave the Armadillo a thousand-dollar shot in the arm. That affiliation carried an endorsement by the highly respected writers Bud Shrake, Gary Cartwright, and Pete Gent, as well as the activist lawyer David Richards and his then-wife, Ann, a future governor. But most of all, the new rock-and-roll joint had that name.

The armadillo is a curious little mammal easily victimized by highway traffic. It has ears like those of a rhinoceros, a tail like that of an opossum, a proboscis somewhat like that of an anteater, and a hard, protective shell around its vitals that scrapes against rocks as it waddles along. It looks like a meek, miniature version of one of those reptilian, prehistoric monsters that Tarzan used to ride among in the Lost Valley. If startled in a roadside ditch, an armadillo is apt to jump straight up in the air and run headlong into a hubcap, knocking itself out. An armadillo tries to avoid getting too far away from a hole in the roots of a brushy tree, and if it establishes a handhold on those roots, Hercules would have a hard time breaking its grip. Yet if an armadillo is captured, it’ll sit in total uncomprehending silence in a corner and won’t fight for its life. A popular Austin liberal politician named Jim Hightower worked the animal into his credo: “There’s nothing in the middle of the road but yellow stripes and dead armadillos.”

When Franklin and Wilson chose the armadillo as a motif they ignored its passivity and tendency to be a victim. In the early sixties a cartoonist named Glenn Whitehead had employed the armadillo in a university satire magazine called the Ranger, and a Texas alumnus responded, “I don’t know what you mean by all those armadillos you’re using, but you better watch out. I’m keeping an eye on you.” But Franklin said he got independently interested in the armadillo. It seemed to embody the plight of Texas hippies—reclusive, unwanted, scorned. And slow-moving, added Wilson: “We’re deep enough southwest that there’s a kind of mañana attitude around here that drives people from New York and L.A. up the wall.”

What else? Franklin shrugged. “Something to do with age. I like the way things look when they get real old. New York, for example, has a certain patina to it that you don’t find in Houston.”

That was the key to it. The armadillo was walking, breathing evidence of times that were different. It was an ancient animal oblivious to modern times. Also, it was a creature whose name had drifted into the Anglo-Saxon tongue by way of Rome, France, and Spain, which implied a more graceful way of going about things, and its habitat was the American Southwest. And because of Wilson’s rock-and-roll joint and Franklin’s art, the armadillo became a symbol for a regional movement, a virtual state of mind. One hippie drifter who had settled in Austin was given to braking to a quick halt when he saw one of the magic animals and to sprinting off in pursuit, yelling, “’Diller, ’diller!” He said he wanted to export them to North Carolina. An out-of-work television producer visualized a rock movie that would begin with an armadillo waddling across a two-lane rural highway straight into the path of a roaring diesel truck—cut to Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen in full cry—then after several reels return to the same armadillo reaching the end of its perilous journey, with the semi mysteriously overturned on its side, wheels spinning and radiator heat rising. The armadillo even challenged the University of Texas. A tongue-in-cheek bumper sticker movement to change the name of the mascot from Longhorn to Armadillo got under way, and students at rival Texas A&M couldn’t let that opportunity slip by. At a Thanksgiving Day football game, the Aggies stampeded a herd of orange-painted armadillos into the ranks of the Texas marching band.

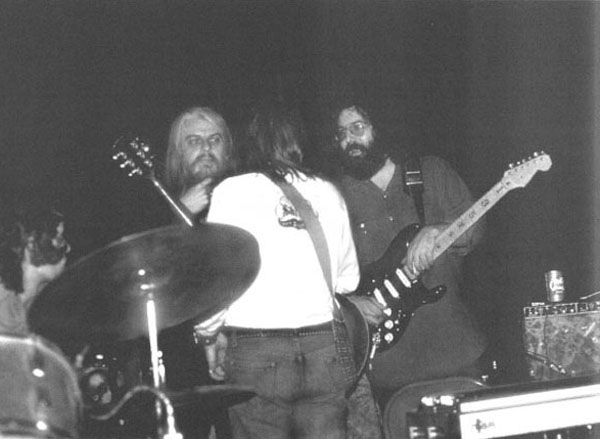

LEON RUSSELL, DOUG SAHM, JERRY GARCIA

Rock Heavyweights. Sahm (back to camera) jammed with Russell (left) and Garcia (right) in this Thanksgiving concert at the Armadillo. 1972.

But Armadillo reality was another matter. The armory was cavernous, filled with acoustical dead spots, and was hindered by lack of comfort, atmospheric misery in winter and summer, and managerial inexperience. The organizers of the Armadillo tried to run the place as a haven for local talent, but they found if they charged enough for the local bands to pay expenses, nobody came. Yet if they let everybody in for next to nothing, that wouldn’t support the overhead either. Finally they summoned the courage to hire a big-name act. In late 1971 they booked John Sebastian for a one-night stand, and the concert lost five thousand dollars. The Armadillo skinned back down to a skeleton crew and tried to hang on to the roots of the tree.

Murphey, Fromholz, and the other country-oriented musicians didn’t come to Austin because of Armadillo World Headquarters. But because most of them played there at one time or another, and because the Armadillo was the favorite hangout of an Austin audience hooked on their hybrid form of music, the Armadillo gained a music industry foothold—a reputation. It was commended to country fans by Townsend Miller, a Merrill-Lynch stockbroker with a journalistic background who wrote a country column for the Austin-Statesman and contributed occasionally to Country Music; and was touted to rock fans by Chet Flippo, a talented writer and graduate student who turned Armadillo journalism into a contributing editorship with Rolling Stone. Other important allies in the press were the co-editors of the feisty political journal the Texas Observer: Kaye Northcott (then Mike Tolleson’s companion) and emerging humorist and muckraker, Molly Ivins.

But before the Armadillo could get to its feet the management had to purchase a beer license, accept a twenty-thousand-dollar gift from a friend, and turn the outdoor area into a beer garden and restaurant. Wilson liked to tell the story of how the Armadillo’s neighbor, the body shop operator Doug Scales, watched the construction of the beer garden and said, “I’ll be damned—I didn’t know hippies would work,” then marched over to shake somebody’s hand and welcome the Armadillo to the neighborhood. What Wilson didn’t say, and what the former constable didn’t know, was that the laborers were drawing daily wages of ten dollars and free beer and dope.

After that, the Armadillo took off. The stage moved from one end of the hall to the other, the acoustics were improved, heaters were installed. Plans were launched to air-condition the place, raise the comfort level, and in Wilson’s words, transform the Armadillo from the world’s smallest concert hall to the world’s largest club. Franklin went off to tour Europe and emcee for Freddie King, and Tolleson started talking in terms of support systems and Phase II. The dream of an arts laboratory was moving closer to reality. The Armadillo was hosting ballet companies and Mozart string quartets, a new recording studio was being installed, publishing and talent management plans were outlined, and Tolleson wanted to move into audio-visual production. He would utilize the half-inch videotape talents of an Austin public-access channel and a commune of expatriate Houstonites who ran a cable-TV outlet in the rural town of Taylor. But Tolleson’s approach to an arts laboratory had changed. “A lot of people have very good ideas and want to put those ideas in motion, but many young people have very negative perspectives toward money and business. Their prejudice limits their potential. I feel now if I’m going to take on something that I feel is very important, the most important thing is trying to see that it works, which entails getting into the financial and business aspects of it.”

Wilson said he wanted to throw in the towel many times, and he spent a lot of time apologizing when a band came to the Armadillo for the first time, but he was booking acts that he once could barely afford to phone. He was able to do that because word had spread among performers that the Armadillo was one of the finest places to play in the country. The appeal of the Armadillo to performers might be broken down into four factors: the carpet, the Coke machine, the lack of cops, and the crowd.

One of the Austin sidemen said of the carpet scrap onstage, “It’s very intangible, very hard to explain. Most places you play you’re standing on a hardwood stage and it’s all very unfamiliar. It’s like the band fragments into separate entities because of the unfamiliarity. But that carpet at the Armadillo gives a band cohesiveness. You can dig your heels into it and make believe you’re playing at home.”

The Coke machine’s appeal was very simple. It was stocked with long-necked bottles of Texas beer that cost a dime.

The absence of cops was more of a mystery. The state of Texas was notorious in its intolerance of things counter-cultural. But though the sight and smell of marijuana smoke was known to stop Armadillo newcomers in their tracks, the Austin police left the place alone, possibly because they knew if they raided the place a riot might ensue, and some politicians and off-duty policemen might be among the take. The only time the cops were known to invade the Armadillo was one Halloween night when pumpkins starting flying.

But the most obvious plus was the crowd: mobile, shouting, native-costumed young people beside themselves with beer, music and the thought of being Texans. The dress wasn’t exotic like in San Francisco; the style ran to boots, jeans, T-shirts, long hair, and cowboy hats. The bellowing mobs scared the daylights out of Bette Midler, exacted smiles of karmic delight from John McLaughlin and the Mahavishnu Orchestra, enticed Billy Joe Shaver to play several times for free, and subjected John Prine to the stifling early-summer heat of the Armadillo. People in the audience said Prine was too drunk to play. Actually he was on the verge of a heat stroke, but he had nothing but kind words for Austin and the Armadillo after his performance.

“I’M NOT REALLY GEARED for a full-dress Armadillo rap,” Wilson said the morning of our interview in 1973. “I’m so damned tired.” Among Austin institutions, the club was now exceeded in importance and visibility only by state government and the university. Looking back at the origins of the Armadillo, he said, “Local musicians were desperate because there were so very few places to play, and they were into an extremely noncommercial sort of music. The paradox of all that was Shiva’s Headband, because they came very close to being extremely commercial, in the sense that they were, throughout Texas, a kind of Underground Heroic Band. They stood for a lot of things that everybody thought a community band should stand for. It was like a microcosm of the San Francisco scene here. The people on the street needed to feel that their fellow street hippies who were making music were into it in a very pure sort of way. Largely a bullshit rap.

“Frankly, I don’t believe in free music. The only free music is when I’m picking for myself on my porch. When it gets any more complicated than that, suddenly it’s not really free music anymore. There’s no such thing as a free concert. The bands may play for free, but it costs somebody something. The typical scam for a benefit is that, all right, the bands need to do this for exposure—not only exposure before a large number of people, but exposure in connection with a cause. Kinda like Mickey Mantle using Right Guard, so it’s okay for everybody to use it. But it’s not always what it’s cracked up to be. A lot of bands overexpose themselves to the point they have to go months without work because everybody’s tired of hearing them.”

Didn’t that outlook alienate people?

“We get bad-mouthed just an awful lot, and I’m beyond the point of worrying about it. We get flak about everything from ticket prices to our attitude. We know the source of our problems, and we can’t explain them to everybody.”

Why did the Armadillo happen when and where it did?

“In Austin a huge percentage of people are here because they want to be here. And because the university is so large and the off-campus community is related somehow in its distant past to the university, the musical sophistication is higher here than elsewhere in the state. You get fifteen hundred people in Houston who really appreciate an act, and you get fifteen hundred people in Austin who really appreciate an act, and those crowds are noticeably different. The people in Austin are looser. They’re not as worried about being shot by a cop when they leave the hall. The only place I’ve ever had a gun pulled on me was in Houston—by a cop—and I’ve got a lot of friends who left Houston because they didn’t feel safe down there.

“The overall mellowness of the situation here is a result, I think, of the power structure here not having the time to jack with the people in the street as much as they do in other places. The power structure here has always been very Washington-oriented, and I think that power structure is now ours, or at least it will be in the next two or three years. We’ve just about inherited it, at least at the street level. In two years, we’ll have that city council.

“People start talking about Berkeley and little towns in northern California and Colorado and Kansas where the freaks got the city council. But it’s never happened in a capital city of a quarter million people with a university of forty thousand students in a state that has cities like Dallas and Houston. When it happens here it’s going to shake the foundations of this country, and it’s going to shake them for the best.”

What would development of a full-scale music industry do to Austin?

“The final product is a pretty good reflection of the desirability of the industry. We’re not talking about something that will result in new concrete highways and high-rise apartments. It needs to happen. It fact it’s got to happen, and it doesn’t have to be bad. A music industry would be wonderful for Austin because it doesn’t pollute and it doesn’t get in the way visually. About fifty million dollars put into the music business over the next few years could be almost invisible. It would take shape in the form of studios and graphic departments and publicity departments all over town, providing work for artists, pickers, and any number of hangers-on.

“The main pollutant of the music industry is the carpetbagger. We’re going to see a lot of them here in the next few months. We’ve already seen a lot of them—all kinds of hustlers coming through here looking for a shuck and a jive, a way to get their foot in the door.

“Personally, I’m looking forward to teaching the Austin establishment something about the music business. The bankers here are just as naive and ignorant as we were in the beginning. Big money is going to come in and put that money into Austin and take it right back out again if the people in Austin don’t snap to the fact that, goddamn, this is better than a new rock quarry or Westinghouse plant.”

What part would the Armadillo play in it?

“I suppose the key to our whole attitude here is our hope to keep changing as often as we possibly can toward greater quality and diversification. Small businesses are supposed to specialize in order to survive, but the specialty of Armadillo World Headquarters is spreading out and expanding. From a business standpoint, that makes very little sense. Up until recently there was absolutely no reason to try to keep the place open. We had proved definitely, on paper, that the place couldn’t make it financially. But we’re still here. Somebody must like us.”

What about the trail boss himself?

“I don’t want to perpetuate the Bill Graham myth that behind every place like this there has to be one driving personality who keeps it together, and when that person quits it’s all got to fold. That’s rat-race horseshit. If I can’t leave the place and have it still continue to serve a purpose in the community and be run by the people who actually ran it all along, and if the people who work here don’t learn and move on and change their interests because they’re here, then the place will get just as stale and boring as any place gets when it’s manned by people working eight-to-five.”

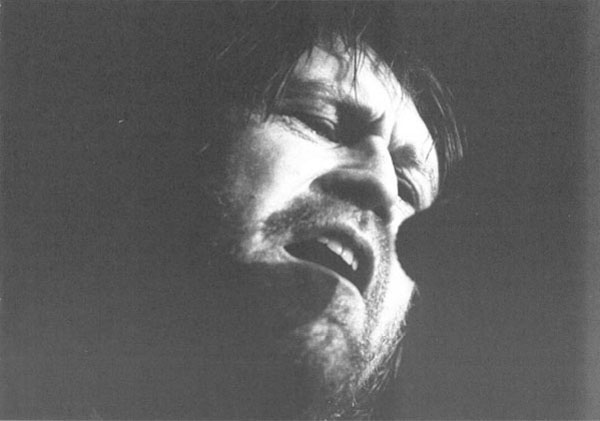

BILLY JOE SHAVER

Homespun Original. Billy Joe Shaver, performing here at the Armadillo, wrote many of the songs that catapulted Waylon Jennings to stardom. Billy Joe’s songs combine rough country idiom and philosophical reflection. 1974.

Another day I asked Tolleson if he thought his Armadillo arts laboratory would ever come about.

“To go into all these other areas,” he said, “will require the talents of more people. Right now our operation is about fifty percent out of control, and unless we establish some kind of order, it will be impossible.”

Did that mean the helter-skelter, all-hands-everywhere days were over at the Armadillo?

Tolleson didn’t like the drift of the question but he met it head-on: “Yes, when you start defining organization, you have to define who makes what kind of decisions.”

The decisions made by Franklin were all creative, as near as I could tell. He was an inspiration to a large stable of bright poster artists; his protégé was a young man with a growling voice who also loved to introduce the bands, Micael Priest. I couldn’t help but appreciate Franklin’s talent and humor, but I didn’t quite know what to make of him. I think I made him uncomfortable, too. “Who were the major influences on your art?” I asked him warily.

“DaVinci, Michelangelo, and Rembrandt, in that order.”

Well, a pompous question deserves a pretentious answer. Someone caught Franklin’s attention and he excused himself, but he paused at the table long enough to show me a cheeping yellow chick cupped in the palms of his hands. “They just brought in some great food for my boa constrictor, so I’m going up to put it in the cage.”

“Where is all this headed?” I asked of the Armadillo, when he returned.