BEER, COCAINE AND . . .

THE FIRST TIME I SAW LUCKENBACH was the day they buried LBJ. The weather was miserable that late January morning in 1973, as if the ghosts of Johnson and Ho Chi Minh were waging one last frenzied battle, and once again, Ho had the upper hand. The rain was terribly cold, somehow refusing to freeze, and it was more forceful than the windshield wipers of the Pinto. The traffic was heavy in southwest Austin, and God knows why the occupants of the Pinto were a part of it. All of them knew LBJ well, or at least had strong opinions about him. The driver dodged the draft by assuring the inspecting shrink that he often dreamed about murdering his mother. The passenger in the front seat had considered overeating himself to a dangerous state in order to avoid having to accept his ROTC commission, then he had raised a piteous wail to U.S. Senator John Tower to get his assignment changed from infantry to journalism. The passenger in the back seat had learned of the Gulf of Tonkin incident while in Marine Corps boot camp, after three days of rumored Chinese invasions and whispered predictions of an international emergency that would require all hands overseas. “Not me,” I told my comrades. “I signed up for six months. They’re going to have to make me go.”

LBJ was an enigma to most Texans under thirty, an awesome figure full of stupefying contradictions. He and Sam Rayburn were the real powers in Washington during the second Eisenhower administration, yet he swallowed his pride and accepted the vice presidential nomination when John Kennedy offered it. His weight on the ticket possibly carried Kennedy to the presidency, but Johnson hedged his own bet, running for re-election to the Senate at the same time. He probably would have been happier the next three years had the presidential ticket lost, for he was shuttled off to supervise the new space program, to endure humiliating rumors of being dumped from the ticket the second time around, and to watch helplessly while John Connally and Ralph Yarborough stripped the gears of his beloved Texas Democratic machine. But then Kennedy was dead in Dallas, and Johnson stepped off the plane in Washington, saying he would do the best he could. The country rallied around him in 1964, and he whomped Barry Goldwater by branding him a reckless fool.

Johnson ramrodded almost everything he wanted through Congress, including some social and civil-rights legislation he probably would have resisted had it come down from another president, and in some quarters he was favorably compared to Franklin Roosevelt at the height of his powers. But blacks were rioting in Watts and Detroit and many other cities, and every winter there would be a cheery assessment of how well the war in Vietnam was going—every summer several thousand more Americans went over to make sure it went even better. As the war heated up LBJ became less of a distant figure. Just being a student wasn’t enough to keep you out of the army anymore; you had to keep your grades up, and if you made the mistake of flunking out they’d nab you before you could get back in. Numerous young women got pregnant to keep their husbands out of it for a while, but then that exemption went the way of others. Everybody was looking for a hole to hide in, be it legal or illegal. Hardly anybody wanted to fight that war. Blame has to rest somewhere, and from all appearances, Johnson was the one who had brought it about, which made him all the more contradictory to young Texans. He was the most notable Texas politician since Sam Houston, but he was making the lives of young men miserable.

I held the line against the Communists one weekend a month in Abilene and stamped out tarantulas in the Mojave Desert two weeks every summer. The administration resisted calling up the reserves because the war was so unpopular. But year after year LBJ seemed to be closing in on me. Finally I sat down in front of the television one evening in 1968, glumly expecting to be sentenced to the petunia beds of Camp Pendleton while the real Marines went off to die, but a suddenly old LBJ announced he wasn’t calling up the reserves. He was stopping the bombing and calling it quits. Johnson had admitted a mistake, the war would soon be over, and Bobby Kennedy was going to be president. I went out and got merrily drunk, my appreciation for the old man already reviving.

In the years after his presidency I saw Johnson for the first time: a tall Cotton Bowl spectator in a gray overcoat who no longer relished the press of the crowd. He seemed forlorn but almost endearing as he returned to his ranch on the Pedernales. His only frequent contact with the outside world was Walter Cronkite; he had grown lax about his haircuts, and judging from the photographic coverage, he played with his grandchildren in a field of bluebonnets a lot. His health was failing, but he could still be the man when he wanted to be. One of his last public appearances was at a civil-rights seminar at the public affairs institute named after him on the University of Texas campus. Attacked by a militant black who commandeered the microphone, Johnson talked hard yet emotional politics while Lady Bird fretted about his health. Black activist Julian Bond said he had differed with Johnson often in the past but added, “By God, I wish we had him now.” Richard Nixon was making LBJ look better and better.

Austin knew and understood Johnson better than Washington ever had, and a hush fell over the city as his funeral caravan moved out toward the Hill Country for the last time. Important government officials made the trip in chartered Continental Trailways coaches, but they were flanked by various makes and models of vehicles bearing mourners, cynics, friends, enemies, and curiosity-seekers from all walks of life. Many of them had cursed and hated Johnson at times, but he was still the mightiest of Texans. At times he had been an almost comic figure, an unwitting butt of those jokes that typecast Texans as blundering, foolish braggarts, but he also symbolized times that were changing, even in Texas. For all his faults, he was one of them. Rest in Peace LBJ, one movie marquee along the way read. Rest in peace, Ho Chi Minh.

Steam rising from their tires, the vehicles moved out Highway 290 west toward Johnson City, past the mock-western storefronts, the barbecue cafés, the last-chance mobile home lots, neighborhoods of tract houses, a fruit stand closed for the winter whose owners proudly displayed a pair of pruning shears with the notice: Hippie Clippers. The city was making its move on the Hill Country. Indeed, a few weeks later Lady Bird would sell most of the LBJ Ranch to a developer from Tulsa. The beauty of the Hill Country would be its ruin one day, after the ranchers passed away and their sons and daughters had to break up their inheritances and sell the land to subdividers. But for the moment it was still a garden inside Texas, even on a wintry day. Most of the country west of Austin was unimproved rangeland where deer outnumbered people and sheep and goats outnumbered cattle. The land pitched and rolled like the sea that once covered it until it finally flattened out into west Texas, but until it got there it was heavily wooded, blue-green and shimmering in the distance. The easterners who ridiculed LBJ’s love of the Hill Country never spent any time in Muleshoe.

The grasses on the hillsides were the color of rust that day, but the view was obscured by the security. There were a couple of potential presidents and saints in those buses and the military helicopters swooped low overhead and Texas DPS troopers waited for trouble every mile or so. Texas DPS troopers always seemed to wear sunshades, even when it was practically dark, and we kept encountering their black stares. Many cradled rifles in their laps. “Billy Graham’s ass,” the driver of the Pinto said. “Let’s go to Luckenbach.”

Luckenbach was Jerry Jeff Walker’s favorite watering hole. Surely we would be safe from state troopers there.

We detoured through Blanco, a small town whose one-time courthouse had been turned into a wild west museum, and followed a narrow winding road bounded on one side by enviable rock houses with working windmills, on the other by a knee-deep river and bluffs that looked like a good place to ambush the U.S. Cavalry. Finally we came to a farm road intersection and a sign that read “Luckenbach 18.” Luckenbach was a former Comanche trading post named in 1849 after the first postmaster, Albert Luckenbach, who later moved a few miles on and settled another village named, naturally enough, Albert. Though natives claimed one of their number got an airplane off the ground four years before the Wright Brothers, Luckenbach was unknown to most people until 1970 when the township was purchased by Cathy Morgan—the gregarious, slow-talking wife of an area sheep rancher—and another rancher named Hondo Crouch. Hondo went to classes barefoot at the University of Texas in the late thirties, excelled on the swimming team, married a landed woman, and years later ran into his old classmate John Connally, who then was governor of Texas. “You still raising sheep around Fredericksburg, Hondo?” Connally reportedly asked.

“Yes I am, John,” Hondo replied. “What are you doing these days?”

Hondo and Cathy took on a working partner in the enterprise. Guich Koock (pronounced Geech Cook) was a young writer who had gone to Hollywood and become an actor, then had come back home. The point of the Luckenbach enterprise was that there was no point to it. People could make their living elsewhere. They came to Luckenbach for beer, rest, and relaxation, and the mock community gained a fairly publicized reputation as a place to get away from it all. Newspaper feature writers were almost as numerous as the chickens for a while. Charles Kuralt of CBS stopped by one day, and Hondo published a poem in the first issue of Place, the splendid offshoot of the Whole Earth Catalogue, bragging that nothing much happened in Luckenbach except the moon.

The road to Luckenbach climbed steeply and peaked finally with a view that would have extended fifty miles had it not been for the gray winter mist. We veered onto another road, passed a sign that read “Luckenbach 2,” then turned in what appeared to be a driveway in front of a large stone house. A man on the porch waved like he had known us for years. Whoever was responsible for those roadside markers must have paid the highway department off. Luckenbach amounted to that one house, a cemetery off in the distance, a collapsing blacksmith shop, a locked-up dance hall, and, at the end of the short road, a weathered building with ancient beer and soft-drink advertisements nailed to the walls. Guineas ran along yelling beside the Pinto. A solitary goat returned our stares.

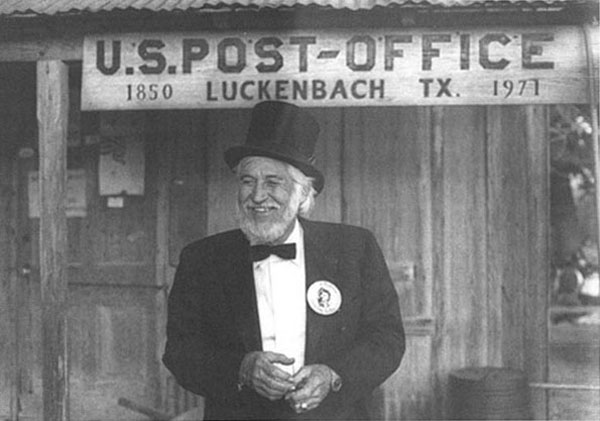

HONDO CROUCH

Everybody’s Somebody. Officiating Jerry Jeff and Susan Walker’s wedding at his hamlet of Luckenbach, Hondo Crouch was a former All-American swimmer who recognized the fun and the cultural ferment at work in a younger generation’s music. His business card read “Imagineer.” 1974.

In one end of the building we found a store that apparently hadn’t done much business in years. Dusty shelves were laden with products from the past—Icon Flakes detergent, homemade lye soap, Wildroot Cream Oil. In the other end we found the bar, walls bedecked with faded newspaper clippings and photographs, cobwebbed hunting trophies, a hand-carved sign that read “Everybody’s Somebody in Luckenbach.” In the middle of the room a hound and her pups snoozed on the floor near a pot-bellied, wood-burning stove. Four men sat around the stove drinking beer. Guich Koock scribbled on a notepad with the look of a man who knew something he was about to tell; a dusty, toothless man in a baseball cap nodded often but drank his beer without a word; and Sonny, a pot-bellied young man with a Fu Manchu mustache and broken-down hat, propped his boots on the stove. The gendarme of the community, a high-strung little man named Benny Luckenbach, spun a web of tales with a thick Tex-German accent. It was impossible not to feel like a tourist in those surroundings. LBJ wasn’t dead; it was 1937, and he was a young man running for Congress.

Benny was talking about one of his neighbors who had gotten drunk, ridden his horse into his dining room, then shot the fool thing when it panicked and began to wreck the furniture. Benny said the neighbor seemed real sorry the next morning, partly because he had a heck of a time removing the carcass from the premises. “You mean that bay quarter horse?” Sonny exploded.

“That’s the one.”

“Why, that old sonofabitch,” Sonny said. “He’s the one that shoulda got shot. When he drinks he gets mean as a water moccasin.”

The four men didn’t jump to greet us, but Guich sold us a beer and Sonny worked us into the conversation. Eventually we felt welcome enough to move our chairs closer to the stove. The talk strayed toward Johnson, and Benny said, “I knew LBJ a long time. When he was president he used to sneak out on the back roads and lose the Secret Service, then come over here and drink beer with us. He was all right.”

Hondo stuck his head in the door briefly and Guich asked him if he was going to the funeral. “Nah,” he said, “I’m figurin’ my income tax.”

After Guich and Sonny went to the burial service we fell into the company of another German-accented man who said he was working on a new expressway in Austin but had a little place, about five hundred acres, near Luckenbach. We traded beers with the man and talked about everybody’s most recent quail hunt—which in my case was nonexistent—then the afternoon crowd began to grow. Three students from Austin came in, followed by a heavyset man with crossed rifles on the lapels of his mackinaw who said he was a trick-shot artist—he had taught Chuck Connors how to play the role of The Rifleman. Our friend listened to the newcomer’s Chicago accent for a while, then stroked his chin and said, “Well, listen here, I’ve got my thirty-aught-six out in the pickup. I’m not any trick-shot artist, but I can hit what I aim at most of the time. Maybe you can teach me a thing or two.”

The Chicago man declined the offer and no shots were fired that day. For the next few months I found myself in Luckenbach often, listening for two hours one day to the unfortunate tale of a farmer who lost all recollection of the conversation after he passed out, recoiling from my first pepper-hominy taste of the south Texas supposed delicacy menudo, watching tongue-tied as a prematurely gray-haired girl sauntered about flipping her hair and drinking beer from a long-necked bottle, driving home drunk a few times myself.

Music was always a part of Luckenbach. Shy couples just happened to have their accordions in the car; Guich played his guitar on occasion; ambitious amateur musicians sat beneath a shade tree passing the latest Texas songs around. But the star entertainer was Hondo. White-bearded and handsome, eyes young and mischievous, he was a wizard with children, a cross between Santa Claus and Gabby Hayes. “Where do you live, little lady?” he would say with a courtly bow, shaking a young girl’s hand.

“Downtown.”

“Downtown Fredericksburg?”

“Just . . . downtown.”

“Well, that’s a pretty good place to live. I been trying to get downtown all my life.”

Unlike Guich, Hondo played his guitar and sang Mexican ballads at the drop of a hat, lavishly trilling his r’s and performing a slow-motion hat dance to the delight of immigrant laborers who drank their beers at Luckenbach. The town had a few drawbacks. Its economic sustenance was beer, and regardless of prevalent friendliness, drunks occasionally turned vomity and mean. And as the weather warmed up the native folk began to be outnumbered by citified pretenders like myself and by older, sunshaded vacationers in dark socks and bermudas who demanded this or that cat be ejected from the premises, they couldn’t stand the things. A few waved their checkbooks beneath Hondo’s nose, hoping that a piece of Luckenbach would allow them move out where life was real.

Hondo handled those customers well. He accepted their beer money but when they inquired about the price of land, he turned his back to them. And if they waxed too overbearing, he climaxed his little Mexican dances with a crazed grin, a crooked elbow, and an upthrust middle finger. Like Kenneth Threadgill, Hondo had turned his advancing age to his advantage; he would be mourned by many when he passed on to his next con. Those two had met once, reportedly measuring each other like aged tomcats, respectful but jealous of each other’s reputation. Hondo mentioned that he was several years younger. Threadgill countered, “Well, I’d a never known it by lookin’ at you.”

HONDO CROUCH was the kind of man Jerry Jeff Walker could relate to. Both were exhibitionists at heart, but both had unhappy things in their lives they preferred to veil. Both were misfits, unwilling to act their age and conform to the roles that society expected. Their philosophy was that they would be dead and gone quite soon enough; they might as well glut their lives on impulse before the last impulse claimed them.

Walker was an upstate New Yorker directed toward music by a sister and mother who sang in an Andrews Sisters-type group and grandparents who played in a square-dance band, and he didn’t establish residence in Austin until 1971. However, his name recognition around town was exceeded among musicians only by Willie Nelson’s and Doug Sahm’s. Walker was a favorite in the folk clubs of the mid-sixties, and when he summoned the classic “Mr. Bojangles” from his web of experience, he wrote the song in Austin. The song about a night in a New Orleans jail guaranteed him income in royalties the rest of his life. He was billed in one of those clubs one night with Hondo Crouch’s son-in-law, and Jerry Jeff said he never knew whether Hondo came onstage or the stage got under him. Every year or two after that he tried to get by to see Hondo, but for a long while he was one of the most homeless musicians in the country. He wound up in jail more often than the bed of some debutante. He often hitchhiked alone, and though he recorded solo albums, he made his reputation in small clubs. When he tried to settle down he took a beating, first in New York and then in Key West, and at thirty-two he was a marvel to Austin musicians. He was still on his feet.

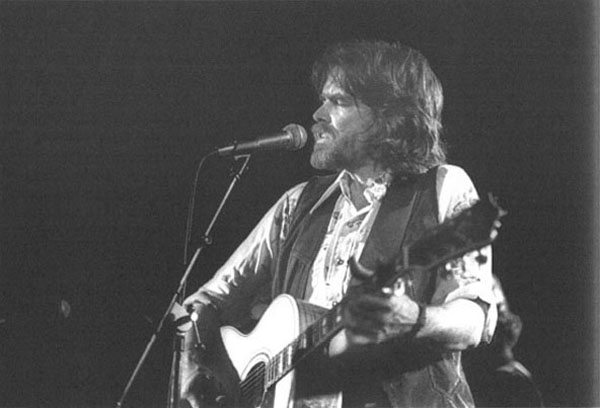

JERRY JEFF WALKER

Jackie Jack. Jerry Jeff Walker celebrated Willie Nelson’s Fourth of July Picnic and the nation’s two hundreth birthday in one of his fashion statements of the times. 1976.

Walker was guarded about his past when he talked to strangers. Looking back on a virtual lifetime of bitter-lettuce hamburgers and stale beer, he’d remark, “It’s damned hard to sing when you’re throwing up.” His friends didn’t deal in specifics when they talked about his past either, but they grew reflective, shook their heads, and marveled, “Man, old Jerry Jeff’s sure done some time.” Some club owners and paying customers thought he was a prick, but musicians appeared to love him. He was the closest thing Austin had to Hank Williams.

When Walker was trying to hang on to his sanity in Key West he started thinking about Hondo and the more conventional rural folk of the Texas Hill Country. Longing also for the easy gigs and grateful audiences in Austin, he made his way there along with his companion, Murphey, and her son. Walker and Murphey lived in Austin for a while before he began to make an impression on local music, but when he surfaced he popped up like a cork. His voice wasn’t what it once was—he had been punishing himself for a decade—and he never had been a prolific songwriter. He wrote sporadically, when the wildness subsided, most effectively when he was on the road performing and had nothing else to do. Many of those motel-room songs were dark and moody, depressing to some listeners, haunting to others. But that kind of song was suited to his style, for his voice was deep and lazy. When he tried to sing rock and roll it was usually a travesty. Though he was a folksinger by reputation, his voice had always been more country than anything else—verging on a yodel in its highest range, rough as a cob on the lowest—and the minute he added a drum to his act, he became a country musician. He was at home immediately.

Walker had a new record deal with MCA and needed to deliver an album. The best band in town was known to work for the perfectionist Michael Murphey. Walker didn’t steal the band; he just happened to be in the right place at the right time. At a rehearsal Murphey blew up over their general lack of discipline and with harsh words stormed out—just as Walker was coming in. In the course of an evening he gained the Lost Gonzo Band. He summoned his New York manager and producer, Michael Brovsky, to Odyssey Studio in Austin. Walker didn’t have many songs ready and Brovsky was stunned by the unorthodox recording facilities at Odyssey, but they had the hottest sidemen in town and a couple of borrowed songs that seemed specifically written for Jerry Jeff Walker. The most helpful sidemen were Herb Steiner, a steel player from Brooklyn, and Lubbock natives Bob Livingston, a bass player, and Gary P. Nunn, a piano player. Nunn wrote some of the most intricate songs they’d ever heard. Also helping out were facile, rock-oriented guitarist Craig Hillis, drummer Michael McGeary, fiddler Mary Egan, and harmonica player Mickey Raphael. The borrowed songs came from a Texan Walker had met in Nashville, Guy Clark. Preceded by a lonesome harmonica, Walker started out easy, and was joined gradually by the pedal steel, piano, and electric guitars that gained continuing force, and a chorus that sounded like a gospel quartet. The lyrics were both a surrender and beginning, a nightmarish wakeup from the American dream of moving ever westward:

Pack up all your dishes

Say goodbye to the landlord for me

Sonsabitches always bore me

Throw out those L.A. papers

moldy box of vanilla wafers

Adios to all this concrete

Gonna get me some dirt-road back-street

If I can just get offa this L.A. Freeway

without getting killed or caught

I’ll be down the road in a cloud of smoke

for some land that I ain’t bought, bought, bought

If I can just get offa this L.A. Freeway

without getting killed or caught

(“L.A. Freeway,” Jerry Jeff Walker [1972])

The cut was a clash of influences on Austin music: a longhaired Teamster crazed by too much speed and too little sex, too stoned to move but in a hurry to get home. And while any Depression Okie could identify with the lyrics, so could any freak who had ever made the mistake of driving an automobile under the influence of LSD.

Another stand-out song had an air of pent-up craziness. This one was a Walker song, but like “L.A. Freeway” it started off soft and country, his voice aided only by an exploring fiddle, then it surged into rock and roll:

People tell me take it easy

You’re livin’ too fast

Slow down now, Jerry

Take it easy, let some of it pass

But I don’t know no other way

Got to live it day by day

If I die before my time

when I leave I’m leaving’ nothin’ behind

’Cause I got a feelin’

Somethin’ that I can’t explain

Like dancin’ naked

In that high Hill Country rain

(“Hill Country Rain”)

The rest of the album was indifferent material, indifferently recorded. Though the album stood out as an unrefined statement of Austin music, and “L.A. Freeway” made one TV-distributed rock-classic album, Jerry Jeff’s statement went virtually unnoticed on the charts. Nationally, his reputation still derived from that one song that he could barely stand to sing anymore.

Of course, a lot of songwriters would have traded lots with Walker. “Mr. Bojangles” transcended artificial divisions of the music audience. No man could ever be stripped of humanity, no matter how low his circumstances. The most downcast man was capable of love, if only for a dog twenty years dead and gone, and art could surface even in a drunk tank, if only in the form of a county-fair minstrel dancer named Mr. Bojangles. Walker’s song had been recorded by everybody from the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band to Bob Dylan to Andy Williams, and Walker got a few pennies every time one of those albums sold. The popularity of the song was pervasive. According to a story that produced guffaws in Austin, Richard Nixon once told a trivia-minded reporter that “Mr. Bojangles” was his favorite song; when he heard Sammy Davis Jr. sing that, it damned near reduced him to tears.

CONSIDER, THEN, the manner of man who sent chills up the spine of the president of the United States. I went to see him at Castle Creek one night in 1973 with an old friend from graduate school. Walker was preceded on the bill by Guy Clark, who looked a little like George Hamilton IV and played quiet music alone with his guitar. The crowd was boisterous in anticipation of Walker, and Clark quickly lost control of them, but he continued playing. He finally quit, then after a long break Nunn, Livingston, and the other sidemen walked slowly onstage and began to play by themselves. Everybody seemed to be stalling.

GUY CLARK

Desperado. A gifted songwriter and frequent performer in Austin, Guy Clark made his career in Nashville. Several of Clark’s songs were memorably covered by Jerry Jeff Walker. 1978.

I knew Walker only by his reputation and his recorded music. I didn’t even know what he looked like. But scanning the room as the sidemen played I recognized him instantly. He was propped against the wall by the rest rooms, tall and stoop-shouldered, hat pulled low over a sleepy look, an oft-broken nose, stubble of beard, a cockeyed grin. With some trepidation I approached him, introduced myself, and requested an interview. Jerry Jeff put both hands against the wall and shoved himself upright, scribbled a phone number on my notepad, and said, “It can’t be tonight. I couldn’t talk to the sun tonight.”

Walker tripped once getting onstage, and he had a hell of a time singing. Then again, he had a hell of a time standing up. Very early in the set he toppled over backward into McGeary’s drums. The sidemen played feverishly at first, hoping to pull him through, but it was hopeless. He slurred and forgot the lyrics, improvised to the songs’ disadvantage, and finally the other musicians relaxed and stopped pretending. Jerry Jeff was a classic drunk, alternately giggling at his foolishness then feeling sorry for himself: “People get down on you, hell, you can’t ever tell.” Halfway through the set he seemed to remember the crowd, doffed his hat to them, and said, “Y’all sure been good to me. If I’d a been in your place I’d a shot myself.”

Actually, a grim Doug Moyes had mobilized his waitresses to inform the customers they could have their money back if they wanted, and many were accepting the offer. Those in the audience who could remember being that down on themselves stayed on to witness the spectacle and sympathize, but others hung around to heckle. “Hey, can somebody at the bar bring me a drink?” Walker mumbled into the microphone.

“Whaddaya want?” a heckler shouted.

“What?” Walker peered into the crowd. “Who is that yellin’ at me?”

“Whaddaya want?”

“Man,” Jerry Jeff responded, “you ain’t got no beer, you ain’t got no cocaine, and you ain’t got no pussy. You ain’t got nothin’ I want.”

Walker couldn’t take a break and then come back to play, so he stayed onstage, sinking steadily while what was left of the crowd hurried to get just as drunk. A pudgy, baby-faced girl stood at the rim of the stage motioning for Walker to come to her, and finally he sidestepped over, grinned, and indicated, Hell, yes, come on up. It was the chance of a lifetime for the girl, and she positioned herself in front of the microphone, wiggled her hips and began to sing “Me and Bobby McGee” in the worst singing voice ever heard in Castle Creek. After she had finished, she expectantly lifted her face toward Nunn, who was playing the guitar, and he dabbed his lips against hers in much the same manner he would have kissed a cobra. They kept her away from the microphone after that, but she stayed onstage, yelling in harmony and breaking into an impromptu can-can routine, a dark bruise glaring from her thigh. Too far gone to care, Jerry Jeff grinned through it all and finally sank to his knees. All in all, behavior outrageous enough to get a good musician’s arm broken in Las Vegas.

The next night Walker showed up clean-shaven and hungover, working hard, trying to make it up to the managers of Castle Creek. He was irritable, threatening to walk out when an unfamiliar harp player jumped onstage to jam, and he pointedly ignored the girl he had invited onstage the night before. She had her hair up for the occasion and a long white gown, and she stood near the stage waiting to be introduced. When she realized what had happened, her cheeks flushed then drained, and she began to circle the club aimlessly, another casualty of the rock generation. The crowd got its money’s worth from Walker that night, but the next evening he showed up in his bathing suit, explaining that he’d been drinking champagne all day. Developing a headache, Moyes looked at Jerry Jeff’s dog, an off-breed collie named Cisco Austin. Walker said Cisco had the best version of “Mr. Bojangles” he’d ever heard.

I MADE AN APPOINTMENT with Walker a few days after that, and he gave me directions to a spacious ranch-style home situated in the middle of a cow pasture near the highway leading to Luckenbach. My friend and I arrived late in the evening bearing tributary six-packs and found a note on the door advising us to go on in, he had gone out for a hamburger. Walker wasn’t as down and out as he sometimes let on. The house was sparsely furnished but equipped with a nice kitchen, fireplace, sliding glass doors. Its floors were even freshly waxed. Walker shouldered through the door after a few minutes carrying a paper sack loaded with beer. He introduced us to Murphey, a big-boned girl with frizzy hair and a voice almost as gruff as Walker’s, and ushered us out onto the patio. He pulled out canvas lawn chairs and we leaned back in front of his swimming pool. The setting was upper-middle-class-anywhere except for the view—an unfenced wilderness populated by armadillos, coyotes, and white-tailed deer. Walker seemed to have the best of both worlds.

I said something to that effect and he said, “Yeah, I’ve been thinking about rigging up a fountain—a statue of Hondo pissing in the pool.” He said he had bought the house from an Austin Volkswagen dealer with no small difficulty. “I’d been wanting a place ever since we moved to Austin, and we finally decided we had the money, but bankers just don’t understand the music business. I made fifty thousand dollars last year, but they’d ask how long my record contract ran, and I couldn’t make them believe the best record deal is a one-year contract. Their system isn’t designed for people who make a lot of money in a hurry and then sit back to spend it. ‘Well, what have you got for collateral?’ ‘A ’47 Packard and a hammock.’ ‘Where do you work?’ But they understand it well enough to hope I don’t have a hit record. They want me to pay all that interest. But this is all right. I wanted a place out in the country, but I didn’t want to get too far away from my work.”

How did he get to Austin in the first place?

“Well, you don’t stop in Longview. I was hitching through about 1964 and I saw Houston—zoom, zoom, everybody moving—so I asked this guy the best way to Austin, stuck my thumb back out, and hitched another ride. After Dallas and Houston it looked like Mecca.”

I asked when he started playing music.

“Oh, I didn’t start playing for pay until I was in high school. But I was singing long before that, and I was listening to the radio. I met a girl at the hop / she left me at the soda shop—I thought, hell, thirty-five-year-old men are retiring writing that. It didn’t look too hard.”

As delicately as I could, I wondered if he was jeopardizing his living by showing up at Castle Creek too drunk to play.

“Oh, I’ve been a lot worse off than that before. And it seems like every time I pull something like that my stock goes up. The club owners figure I’m good-time Charlie, so they keep asking me to play. From February to April, I was on the road in Chicago, New York, Philly, Austin, Dallas, Denver, Seattle, San Francisco, and L.A., and I was supposed to stop performing in May. But then we did Kerrville and the Saxon Pub and it was July and I was still performing. Good times all right, but a string of good times can mean you’re getting nothing done. So I misbehaved at Castle Creek. I’ll make it up to them. But I had to get to work writing. We’re going to do an album in Luckenbach in August.”

Walker was one of those performers who froze up when he walked into a professional recording studio. He couldn’t clap earphones over his skull, lay down a basic track with his bass player and drummer, then relinquish the work to the mixing engineers and studio sidemen and call that his music, even if that was the way it was often done. He wanted his pieces recorded exactly the way his band performed them, which was the reason he took his business to Odyssey, the reason he wanted a mobile recording van in Luckenbach. He wanted to make music where he was comfortable, and Hondo Crouch’s Luckenbach struck him as the most comfortable place he’d ever been. Brovsky and the sound truck arrived in August of 1973, and the musicians rehearsed under the Luckenbach shade trees, swapped stories with Hondo, and drank his beer, then disappeared into the truck to record another song. On the last night of the session they lifted the ban against outsiders and went into the dance hall to record some more in front of a frantic crowd of transplanted Austinites.

Walker recorded enough material during the week for a double album, but MCA vetoed that idea. Hondo’s reading of his poem got edited out, but the album had a decided Luckenbach flavor—photographs inside and outside the cover, an explanatory essay from Walker, and a title, ¡Viva Terlingua!, borrowed from a poster on a clapboard wall advertising a chili cook-off in a west Texas ghost town. But even more than the first Austin album, ¡Viva Terlingua! was emphatically Walker, emphatically Austin. The album was marked by momentary instrumental brilliance, more than a few bad licks, a study of Walker’s failing voice, a happy revolt against the established procedures of Los Angeles rock and Nashville country.

The best cut on the album, Guy Clark’s “Desperados Waiting for the Train,” was an emotional song about a boy growing up in the north Texas oil fields while the wildcatter who raised him grew old and died. A couple of throwaways marred the album, but they were offset by a country version of one of Walker’s old divorce songs, “Little Bird,” and another moody song, a vision of automotive death called “The Wheel.” Those were two of Walker’s better poetic efforts, but once again other songwriters gave the album much of its raucous, Luckenbach-saloon flavor. One of those was Michael Murphey’s “Backslider’s Wine,” but while Murphey sang the drunken confession like he was at the altar praying for forgiveness, Walker sang it from the gutter. Another, written by a Texan named Ray Wylie Hubbard who drifted between Austin, Dallas, and Nashville, was a classic rebuttal of Merle Haggard’s “Okie from Muskogee.” As they told the story, Hubbard had been with Bob Livingston in Red River, New Mexico, and had been sent off to bring back beer. “I walked in this bar,” Hubbard would say, “and they took one look at me and ate me up.” He came back and wrote the song for his friends. Years later Livingston was playing the bass one gig when Walker broke his guitar strap. Walker told Livingston to sing something, and he delivered “Up against the Wall Redneck Mother,” as best as he could remember it. The audience went wild, and Walker decided it was a song his repertoire needed. Midway through Walker’s performance Livingston would step up to the microphone and recite:

M is for the mudflaps

you give me for my pickup truck

O is for the oil I put on my hair

T is for T-Bird

H is for Haggard

E is for eggs and

R is for . . . redneck!

Walker stepped aside on the last cut of the album in favor of Gary P. Nunn. Nunn had helped Walker immensely—as arranger, piano player and guitarist, vocal accompanist, and in times of drunken vulnerability, something of a mother hen—but he was also an accomplished songwriter, and he appeared to be the Austin sideman most likely to make a move of his own. Strung out over seven minutes, the lyrics of his song were as sardonic as anything John Lennon ever wrote, but they were the pitiful wail of a Texan marooned in the British Isles:

And them limey eyes were eyeing a prize

that some people call manly footwear

They said you’re from down South

and when you open your mouth

you always seem to put your foot there

I wanta go home with the Armadillo

good country music from Amarillo and Abilene

The friendliest people and the purtiest women you ever seen

(“London Homesick Blues”)

MCA bought full-page space in several magazines to promote ¡Viva Terlingua!, but it never really caught fire nationally. Stereo purists and radio executives sniffed that it was poorly recorded, yet the album assured Walker’s reputation in Texas. Just when Nelson or Murphey released a new album that seemed to establish them as the leaders of Austin music, Walker came out with another funky one and turned everybody around. Though he didn’t act like a leader and disclaimed all ambitions to the role, if there was a spokesman for Austin music, Walker was it. He wasn’t a Texan in origin, but he was a hot act in Texas, if nowhere else.

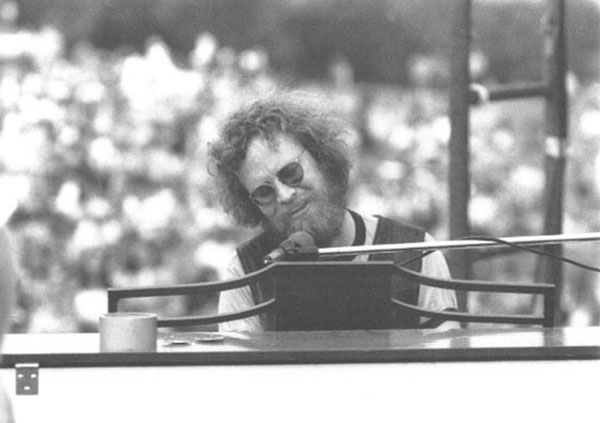

GARY P. NUNN

Home with the Armadillo. With Jerry Jeff Walker and the Lost Gonzo Band on ¡Viva Terlingua! Gary P. Nunn wrote and recorded the song that became the anthem of progressive country and Austin City Limits. Gary always had the gift for setting the dancers swirling counter-clockwise in country roadhouses. 1975.

A Jerry Jeff Walker appearance became an occasion. He finally had enough clout to stay out of the clubs more and focus on the less exacting concerts. The manager of the Country Dinner Playhouse was amenable since Michael Murphey had proven to be a gentleman in the first concert and generated some badly needed revenue, but KOKE, which by then had a piece of the action, was wary because of Walker’s antics at Castle Creek. But Walker was riding a crest of popularity, he had the best band in town, and he enjoyed performing for the time being because he had added horns to his sound. Country rock had gone Dixieland.

Writers and artists, professors and physicians stood in long lines to get in the Jerry Jeff concert at a dinner theater, along with a bearded man who seethed at the thought of people who would sell him an advance ticket but could not assure him a seat near the stage. “I demand to know why not,” he accosted the producer. “This is an outrage.” Neckties prevailed, not blue jeans. Murphey made her appearance in a comely black dress, the wife of KOKE’s Ken Moyer talked with a small measure of distaste about the Commander Cody concert she had recently witnessed at the Armadillo, and an Austin bootmaker whom Walker had saluted in his Odyssey album, Charlie Dunn, walked slowly to his table accompanied by his wife, who wore a long gown and walked with a cane. Walker’s song had made the bald little man locally famous, but Dunn had never seen Jerry Jeff perform.

I had the good fortune of a seat at the table of Hondo Crouch, Luckenbach co-owner Cathy Morgan, and her husband Ken. Hondo had been a character in Austin for years, but he became even more of a celebrity now that he was Jerry Jeff’s heralded sidekick. Hondo continually showed up at Walker’s concerts, and often as not, he stole some of the show. Once in San Antonio he staggered drunkenly onstage, tripped over the microphone cord and hit the floor with a frightening crash, then jumped to his feet and said, “Now that I’ve got your attention . . .”

Hondo was a handy man to have at the table that night, for the theater’s management refused to sell beer for the concerts. Hondo lifted the tablecloth and peeked down at his feet. “How many beers we got?” he said. “Whose pickup are we in?”

Long-necked bottles of beer materialized one after another from underneath the table, and Hondo patted me on the head occasionally and invited me to take a pull off his. With a reputation of their own by then and the name the Lost Gonzo Band, Walker’s sidemen occupied the stage and Nunn said, “We’re gonna play a few songs before the lead egomaniac comes out.” Recently enlisted guitarist John Inmon took his turn in the spotlight, followed by Livingston, and then Nunn. As Nunn finished his last piece Walker slouched onstage wearing a brightly flowered green shirt, nodding and grinning at the flashbulbs that popped in his face. Jerry Jeff was at his best that first show, friendly and accommodating with the crowd but wired into his music, particularly after the horn players came onstage. But as one crowd left and another fought its way in, the performance began to deteriorate. The manager of the place stared wide-eyed as the white-bearded figure of Hondo Crouch trooped by shouldering an immense cooler full of beer, and for the second show the musicians staggered out of the dressing room. The music wasn’t half as tight, but the people spitting tobacco juice on the carpet and drinking themselves to oblivion didn’t seem to mind.

“Is Hondo still here?” Jerry Jeff said at one point.

“I am, but Cathy’s passed out,” Hondo shouted in reply. In just over an hour the Country Dinner Playhouse was reduced to shambles. The manager reeled when she saw her place empty, for her Dallas superiors were coming down the next night and her job was on the line. The producer and a crew of workers spent most of the next day cleaning the auditorium, but it took the manager an equal amount of time to restore order in the performers’ dressing room alone. Finally she emerged with two handfuls of stubbed-out reefers and a great number of pills. “My God,” she said. “They were so far gone they couldn’t even get these things to their mouths.”

IT WAS WINTER AGAIN, and I drove out to Luckenbach one Sunday. Hondo and Cathy weren’t around, and neither was Guich. His partners had balked when he tried to sell his working share of Luckenbach, and he was off somewhere preparing for nationally televised tryouts to launch the career of a new Singing Cowboy. (He came in second.) Walker wasn’t around either, but his presence was everywhere: posters on the wall, albums for sale, a portable phonograph playing ¡Viva Terlingua! over and over, one young man displaying the snapshots he took at that Saturday recording session, another who had the unedited, Saturday-night performance on his cassette player.

The latter sat near a drunk farmhand and an older rural man with a Tex-German accent like that of Benny Luckenbach, only this old-timer wasn’t so fond of LBJ.

Winking condescendingly at times and cutting the old man off frequently, the young man demanded, “Do you think Nixon’s better than LBJ?”

“One side’s heads, the other side’s tails. Nixon got caught.”

The young man snorted and the old-timer said, “Listen, little buddy, I don’t know you, but I knew LBJ all his life. The only time he ever had a lick of sense was when Court Mortimer knocked him off that jackass with his lunch pail.”

The sun was almost gone, and I was ready to go back to town. I didn’t know how long it would be before I would want to return to Luckenbach. It would soon be spring again, the tourists would be descending with their checkbooks, and the real people of Luckenbach would retreat to the hills. I hadn’t seen the gray-haired girl in over a year. Somebody told me she had a crush on some guitar player.

Jerry Jeff went off to play Carnegie Hall with the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, but he didn’t have a new album to take along. Most of the leading Austin musicians had come out to help him record another album at Castle Creek, but the recording session didn’t work out. Jerry Jeff’s band, his pride and joy for so long, threatened to dissolve because of personality conflicts. Murphey and her son went back to Florida. Like the Hill Country he loved, Jerry Jeff’s life was a series of crests and valleys. I turned on a San Antonio station one day in time to catch the ending of the Luckenbach album’s lead cut:

Income tax is overdue

and I think she is too

Been busted and I’ll prob’ly get busted some more

But I’ll catch it all later

Can’t let ’em stop me now

I’ve been down this road once before

(“Getting By”)

The disk jockey said afterward, “Hey, Jerry Jeff’s playing out at St. Mary’s tonight. You oughta go out and see him. He’ll be good out there, they don’t have anything for him to drink. No, I mean it. He’s good when he’s sober.” Disk jockeys can be dreadful smartasses sometimes. Let it slide, Jerry Jeff, let it slide.