THE GOLDEN FLEECE

OF ALL THE RECORDING ARTISTS in Austin, Bobby Bridger was the easiest to overlook. He rarely performed, and when he did, few people seemed to take interest. His music could be intoxicating, but it was the intoxication of a thoughtful glass of wine. Austin was a beer-drinking town. Even in appearance Bridger seemed a misfit. He wore a hat to conceal encroaching baldness, but it was the kind of hat one would expect to see in New England, not Texas. He wore hiking boots, not cowboy boots, and the rock-and-roll influence on his music was negligible. When he performed he sat on a stool with his legs crossed, played an acoustic guitar with nails grown extraordinarily long on his right hand, doffed his hat to applause, explained the circumstances of his songs. In his speech he was afflicted by the nasal twang that marked us all, but his songs told stories set outside Texas, and his voice was high, soft, and silken—too pretty, some thought, for a movement associated with life in Texas. He drove an Oldsmobile instead of a Volkswagen van and spent most of his time with his stepchildren and wife, a university Ph.D. candidate and an English lecturer at the community college. One country music writer prefaced every mention of Bridger: “Now Bobby’s always been a bit too folkish for my taste . . .”

Yet Bridger was impossible to ignore. He had written and recorded two albums for RCA, and except for Nelson, he was the only major Austin performer with a legitimate country career behind him. Bridger’s real name was Bobby Durham. He had a natural affinity for Texas as a youth, for his father’s family lived in the piney woods in the eastern part of the state, but he grew up in Louisiana. When he enrolled at Northeastern Louisiana State in Monroe he wanted to be a sculptor, but his singing at campus talent shows attracted the interest of a would-be ballad collector who had once assisted the folklorist who discovered Jimmy Driftwood (who wrote “The Battle of New Orleans” as a history lesson for his students). The folklorist asked Bridger to join him in a project that would take them into the Ozark and Blue Ridge Mountains in search of authentic folk ballads. Bridger spent most of the time opening gates and manning the tape recorder, but occasionally the folklorist delivered a lecture on the influence of Elizabe-than language on backwoods music, and Bridger played his guitar and sang to illustrate the lecturer’s points. Bridger was gradually realizing he was better at teaching sculpture than creating it, and he was interested in that approach to music. He doubted there were many young men in the United States who were interested in spending their lives collecting story-telling music, so he figured the field was wide open. He was also a talented singer and songwriter, and he was approached with a dozen recording offers, but he turned them down. He didn’t think he wanted anything to do with commercial music.

Then he married and started teaching high school art in West Monroe. High school teaching was a one-way track toward semi-respectable poverty and a thankless principal’s job at the age of forty, and realizing that, Bridger signed a contract to record with Monument in Nashville in 1967. The school administration tolerated the arrangement, though they stressed he was not to allow his “Memphis honky-tonking” to interfere with his teaching. Bridger had a pretty country voice, which was then all the vogue. A session guitar player named Glen Campbell had taken “Gentle on My Mind” from its more rough-hewn author, John Hartford, and made them both a fortune, and Monument wanted a piece of that action. Bridger found himself razor-cut and hair-sprayed, traveling on the weekends with a big band that always featured a pretty, blonde vocal accompanist. If one got married or pregnant, Monument always found another. Several of his singles received airplay—one made the country charts in England—but after three years of drifting away from the kind of music he wanted to play, he abruptly quit. He freed himself from Monument very easily; he tore up his contract and threw it away.

During those Nashville weekends Bridger chanced upon a fishing trip with Paul Simon, who struck him as an egocentric beyond redemption, but a wizard of songwriting. Simon listened to some of Bridger’s songs and said he was telegraphing his lyrical punches; his songs were too predictable. Bridger’s songs began to pour out after that, and he decided to record and produce his own finished tape. After borrowing the money and recording his album in Fred Carter’s studios in Nashville, Bridger got a list of recording companies’ addresses and went to those offices with his tape, but he had no luck in New York, Nashville, or Los Angeles. “RCA rejected it twice because I was dealing with peons,” he said. “Rookie producers are afraid to make any decisions because if they make a good decision, the guy up above them is going to fire them because his job’s threatened. I found that out very rapidly. Then getting into the offices of the people who could make decisions was just next to impossible, so in essence I’d lost on the thing, and was in bad shape financially.”

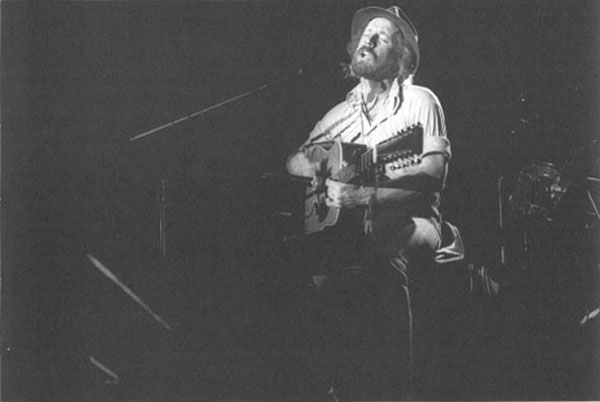

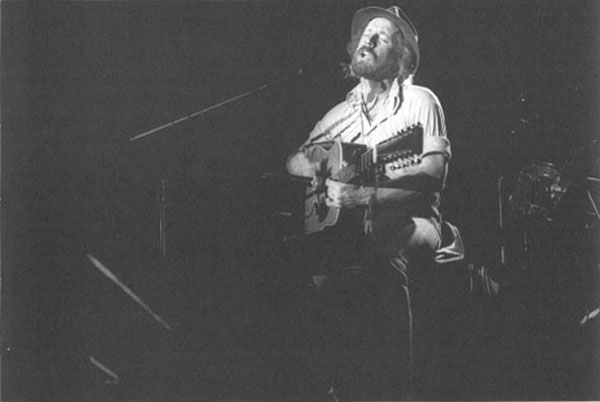

BOBBY BRIDGER

Vision Quest. Bobby Bridger reimagined the frontier spirit of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and embarked on a narrative adventure that has embraced his long career. 1978.

Bridger went back to Louisiana with little hope left for his music career, but then his business manager played the tape for a church-going Louisiana cotton farmer, who liked it and asked for permission to see what he could do. The farmer took the tape to an old classmate who owned a chain of movie theaters based in New Orleans. The theater owner said he didn’t know the first thing about the music business, but he forwarded the tape to his son, Jay Houke, who was handling the highly successful distribution of the communal cinematic attempt, The Legend of Boggy Creek. Houke took the tape to Los Angeles, talked to the right man in the right office of RCA, and suddenly Bridger was under contract again.

On Merging of Our Minds, Bridger was backed by as many as six sidemen, two vocalists, and even the Gulf of Mexico on a seven-minute tale about men adrift called “Sea Chanty,” but the tone of the album was set by love songs. It was an impressive album, but it connected with a limited audience.

While in Los Angeles Bridger’s manager ran into a man who said he was completing a movie and needed a singer to record the theme. Bridger played for the man, aware that movie producers were a dime a dozen in every Los Angeles bar, and was shocked when the man called three days later and said he wanted Bridger to write and sing the theme. The Wheel was set in a junkyard and had only three characters and twenty minutes of dialogue, so it naturally flopped in America, though moribund Look magazine called it the first serious American art film and it became popular in Europe. But the movie was the vehicle that brought Bridger to Texas. The people behind the film decided to premiere it in Austin, and they wanted Bridger there.

Bridger liked Texas and had heard good things about Austin, and his wife was able to get a teaching assistantship at the university, so they moved there in 1970. RCA never seemed to know quite what to do with Merging, and though Bridger went on the road to promote it, the album slipped beneath the surface and drowned. Even in Austin he was practically unknown, though Rod Kennedy put him onstage at the second Kerrville Folk Festival (1973) after Mance Lipscomb’s health forced him to cancel. Still, Bridger’s music benefited from his association with RCA. His second album for the company, And I Wanted to Sing for the People, was better than the first. Backed by three vocalists, mandolin, dobro, synthesizer, strings, and even a celeste, Bridger’s songs were subtly, tastefully done. The album contained an upbeat soft-rock number called “Ragamuffin Minstrels,” but the quiet Bridger was still in command.

The album clearly indicated the influence of Paul Simon on Bridger’s songwriting. Bridger was not Simon’s equal, but he was learning to economize his language and his writing was much improved, though he still needed to establish his own sense of direction. In fact he already had. It was a song called “The Call.”

A lonesome old Indian lives down deep in my heart

And he speaks without making a sound

And he walks through my forest and hunts for my thoughts

And he knows a man I haven’t found

Yes the Indian lives on the plains of my mind

And he sings with the coyotes at night

And he wants me to leave this old city behind

’Cause the way concrete feels just ain’t right

Though the album received more airplay than the first one had, it also lacked a big promotional push by RCA. Bridger’s songs and arrangements were adequate, but his voice failed to meet the new criterion for success. In the ever-changing fashion, it wasn’t distinctive enough. In order to make an impression, a singer’s voice had to be rough as a cob; the listeners had to be able to identify with its imperfections. Ironically, Bridger had already lost his voice once and undergone surgery to remove nodules on his vocal chords—a singer’s occupational hazard that afflicted the likes of Rod McKuen, Joe Cocker, Rod Stewart, and Austin’s Michael Murphey. Yet when Bridger recovered, his voice was still too pretty for the prevailing American market. The melodic voice seemed like a ghost from the past.

One Saturday in 1973, Bridger agreed to come to the house of my friend, the photographer Melinda, in Austin. He entered and took a seat on her sofa and removed his hat, which, he told us later, was something he rarely did. He had started wearing a hat as a teenager because he thought it made him look older. Now that he was fast going bald, he thought it made him look younger.

I asked Bridger what he thought of Nashville.

“I became disenchanted with Nashville because I didn’t like what was happening there. I think Nashville is a fascist town. For one thing, it’s the Rome of the Southern Baptist Association, and all the hang-ups of Southern Baptist philosophy concentrate there.

“Most of the writers and musicians in Nashville come from the South. When I went there I was a folksinger, for lack of a better definition. The guy who signed me knew I was a folksinger, knew that my concern was more artistic than commercial. But when I got there the first thing they made me do was start cutting slick country music. I went into country music because of that. I was looking for a hit in order to do what I wanted to do.

“That was my first awareness of the record business. The whole approach is, You do what we want you to do first, and then you can do what you want to do. So I said okay, and after about three years I was wearing my hair the way they wanted me to, singing the songs they wanted me to sing, doing everything they wanted and still going nowhere. So I quit and said I didn’t want to have anything to do with this anymore.”

I said he differed from many musicians because he enjoyed working in a studio. What made him want to get into the production end of it?

“People are always talking about the sterility of a studio, but I think if a person’s music is on his mind, then it doesn’t make any difference where he plays it. The studio is a place where I can create a void, a vacuum, where I can eliminate all the distractions and allow my thoughts and energy to concentrate. To me, saying you can’t get a good sound in a studio is like a carpenter complaining about his tools. A good carpenter doesn’t complain about his tools; he’ll build the house anyway.”

I observed that although he had been in Austin longer than most of the other recording artists, he was still a musician apart from Austin music. He said he didn’t mind that at all. “The reason I came here was because it was different from Nashville. Quite frankly, I was healing when I came here, because I’d been through a long ordeal with my first album. Austin was so refreshing. There were people in the music business here who were completely aware of the economic structure of the music business, yet they were unaffected by it. They hadn’t been stung by it like I’d been.

“I liked that a whole lot, but now I think Austin’s being taken over by the other music centers, and that’s a very common thing. It happened to Boston in the early sixties when it became a center for amateur folk performers. The next thing you knew Vanguard and Prestige and Elektra and all those labels were signing those acts, and Boston became a real hotbed. But then the next thing you knew, Boston was no longer a part of it.

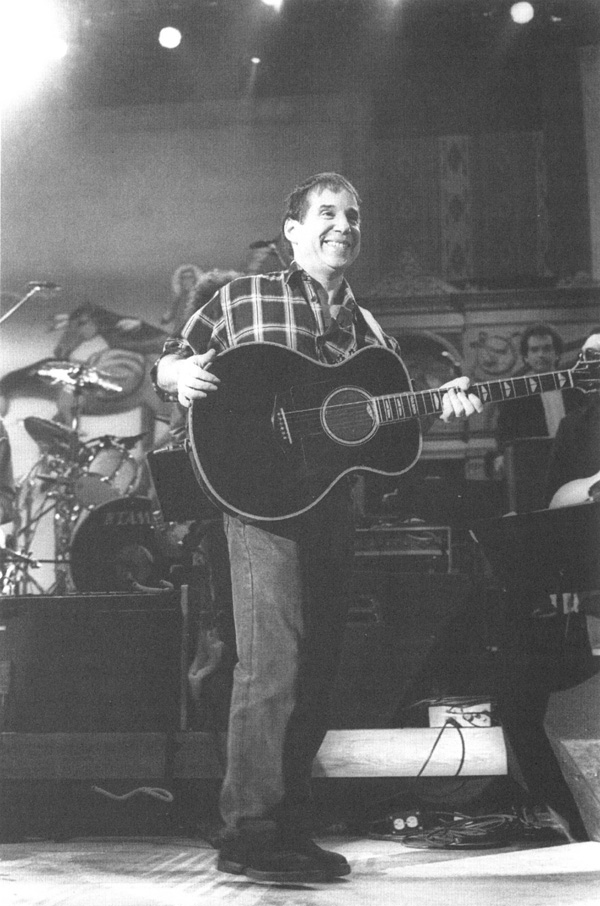

PAUL SIMON

Influence and Craft. One of his generation’s most distinguished American songwriters, Simon inspired and counseled Bridger. He is shown here performing at Willie Nelson’s sixtieth birthday concert. 1993.

“I’m afraid that’s going to happen here, and that’s a real shame because what Austin offered to me was a new approach to the music business—a community approach to cope with economic problems that appear when someone is trying to break in. We’ve got a lot of talented pickers and writers here and we’re collecting a good amount of gadget freaks—studios are basically monuments to gadget freaks. The scene that has developed here will probably accomplish what people want, and people desperately want a music center here. They’re supporting it, and that’s good and fine. I like that aspect of it. But unless some directional force is given to this then it’s going to be a shot in the dark. It’ll form a music center, but that’s not going to help the people out there starving in the street. What it’s going to do is create offices they can’t get into. That’s all it’s going to create, unless Austin has enough foresight to see the mistakes other music centers have made.

“In other words, why do they want a music center here? It’s obvious by even wanting to form a new music center they’ve become dissatisfied with the other ones. So why not make it something that’s different? I think it’s time to examine our motives. Unless we start doing some serious examination of what it is we seek, then we’re going to end up perpetuating the same thing we’re all up against. But everybody’s too busy jumping on the bandwagon to give any thought to where it’s headed.”

Bridger said the only reason he was still in Austin was that his wife hadn’t finished work for her Ph.D., and added, “In order to make a name in Austin, you have to play a bar every night in order to get your name in the paper. Either that or you’ve got to be a member of some clique that associates you with a certain scene. Right now you’ve got to be one of the cosmic cowboys, and I think it’s a very dangerous thing to associate oneself with a movement, because the music business is a vacillating, fluctuating, constantly moving thing. People may be ready to jump on the maverick cowboy bit right now, the thought of being a conforming rebel. But I think that’s strictly a fad. That may be open to argument, but music changes very rapidly, and people who identify themselves solely with country music are going to find themselves wondering in two years how in the world they’re going to continue.

“You can hardly go out in Austin without hearing somebody complaining about labels put on their music, yet what they’re doing is rigidifying a new label, and they’re endangering Austin. An analogy might be John Denver singing songs about people raping the mountains. He’s singing that to an incredibly mobile public which is looking for some kind of authenticity, so they’re going to go to the mountains and rape them. He’s perpetuating the whole thing.”

Did that mean he was divorcing himself from Austin music?

“No, I’m going to start performing more in Austin, not to sell records particularly, but because I want to get in touch with some of the people in Austin who think there is something besides hip country. I want the few people who find themselves drawn to my music to be there to listen when I play it.”

BRIDGER WAS RESPONSIVE but soft-spoken that day, his remarks punctuated by high-voiced laughter, but there was an underlying tension in his manner. In performance, he seemed the most relaxed, retiring musician in town. He responded personally to a crowd’s applause and assumed they responded personally to his music, and he was never rough on the ones who stumbled into Castle Creek in search of their fifth tequila sour of the evening. He was too polite for that. But he wanted desperately for them to listen. His was a perfectionist’s music swimming with ideal loves, ideal places, ideal solutions to universal problems, uninhibited turtles in the creek and butterflies. And most lately, mountain men and Pawnees and coyotes. A suggestion of what he was about to offer the music world, if he could get a company to record it, was laced all through that song “The Call” on the second album.

The project started out as Bobby Durham’s reading interest in a historical figure who might have been his relative. He had reason to believe that the mountain man Jim Bridger was a great-great uncle on his mother’s side, and he attached enough significance to the possibility to change his name to Bridger. He picked and poked at Jim Bridger in books from the time he was old enough to read, gaining one impression of the man from juvenile historical novels, another from jingoistic public school textbooks, various others from academic histories. But one day, searching through a rare book collection, he ran across a slender volume called The Song of Hugh Glass, by John Neihardt. Neihardt was best-known for the 1932 Native American classic, Black Elk Speaks; but he was also poet laureate of Nebraska, and The Song of Hugh Glass was part of a nine-volume epic poem called The Cycle of the West, which recounted American history from 1820 to 1890. Twenty years old when he found the book, Bridger devoured that work and decided he wanted to write a similar piece of music. Through his Nashville and Austin days, he played what music he could, going through hell in his mind as he dealt with music-business professionals whom he considered essentially evil, unearthing more material for his project as he went along. He never communicated with Neihardt, but the example of the older man was always out in front of him. “I wrote Neihardt about twenty letters I never mailed,” Bridger said. “If you ever suffered from professor worship you know what I mean.”

Neihardt died before Bridger completed his work, but by late 1973, Bridger had given seven years of research and writing to his project, and the first part of it was almost ready. Though Bridger stood apart from his Austin colleagues in his approach to music, he was personally close to many of them. John Inmon, Leonard Arnold, and several other sidemen helped him record a rough demo tape in a makeshift bedroom. The new album was to be called Jim Bridger and the Seekers of the Fleece, a long narrative poem versed in heroic couplets and interspersed with nine songs voiced by Jim Bridger, Hugh Glass, Jedediah Smith, a Blackfoot warrior, and an omniscient narrator.

Bridger’s story picked up the trail of American history in 1822 in St. Louis, when Jim Bridger, an eighteen-year-old orphan and runaway blacksmith apprentice, joined the Ashley-Henry beaver-trapping expedition west. Other members of that expedition were Smith, a Calvinist minister who pioneered two overland routes to the Pacific before he was killed by the Comanches on the Cimarron River in 1831; and Glass, a gray-bearded loner who had lived with the Pawnees and was later killed and scalped by the Chickarees in South Dakota in 1833. Smith was one of the only members of the hundred-member band who could read or write, and his glowering presence made the others pretend to be reverent, even if they weren’t. Glass was a naval captain said to have been captured by Jean Lafitte’s pirates, but he escaped and walked upland to Kansas, where he bribed his Pawnee executioner with a piece of vermilion. He lived with those people several years and learned their methods of stalking game; thus he was the expedition’s hunter. All those men, Bobby Bridger believed, were men on the run from the civilization east of them. They were anarchists, he wrote in his journal, “in the finest sense of the term.”

Bridger’s story continued: Glass befriended Jim Bridger and trained him as an apprentice hunter, but in 1822, because Bridger was too slow to react, Glass was badly mauled by a grizzly in South Dakota. Bridger and another volunteer, lured into the assignment by an eighty-dollar purse, waited for Glass to die, but he lapsed into a coma and hung on. Bridger and the other man were afraid of surrounding Indians, so finally they left Glass to die and took his gun to their comrades with the expedition as evidence of his demise. Glass survived somehow, crawled two hundred miles to Fort Kiowa, then made his way another four hundred miles to Fort Henry, where he confronted Jim Bridger. Glass forgave Bridger, because of his youth, then he went off in search of the other betrayer. In Bobby Bridger’s story, Jim Bridger was driven by the humiliation of that day to strive to be the one out front, the one who volunteered for the most dangerous assignments. Because of that, the researcher continued, Jim Bridger was the first man to the Great Salt Lake, and unlike the others in his company he kept his scalp long enough to witness the coming of the Mormons, the death of the buffalo and beaver, the encirclement and theologized extinction of the Indian culture, the submission of the West to a plundering civilization.

It was a subjective interpretation of history, but Bobby Bridger believed in it, and he attached special significance to it. The mountain men, he believed, were the only anarchists in American history who had made their system work, if only for a while. Their flights from ordered society opened roads that the same society quickly poured over, but they regained what an expansive America had lost: a sense of being at one with nature. Looking around in the twentieth century, Bobby Bridger knew that sense of communion was really lost now, for Americans treated their country as if there would always be more land out West to move on to. Soon it would be a civilized wasteland of fetid pools and orange skies and tall buildings founded on garbage, unless there was a revolution in consciousness. Aside from soaring prices and energy crises and the deepening cesspool of Watergate, Bridger believed that the real evidence of ruin in America was the pollution, the gluttony, the enormous waste masqueraded as progress. That was the real message of Bridger’s writing. The mountain men had procured the fur of the beaver for the stylishly ravenous society east of them, and now that society had fleeced a continent. He was trying to project a nineteenth-century message into the twentieth century.

The trouble was, he was locked into a twentieth-century medium. If he was going to disseminate that message among very many people, he would have to do it on record. But there was no market for his music. He wasn’t a rock and roller, the folk movement was a thing of the past, and though he wrote about the preservation of the countryside, his music lacked the instrumentation, inflection, and suburban obsession that had become the hallmarks of “country” music. RCA rejected the album out of hand at Bridger’s first mention of it. Concept albums were problematic enough even with highly popular, widely known artists, for the listening public had been trained to take its music in small doses, four or five minutes in passing. What advertising-minded radio executive was going to set aside fifty-five minutes of programming for an American history lesson from a practically unknown folksinger, and even if they did, how many consumers would rush to their record stores for that? What was American history anyway? In an era of truck-driving snipers, Secret Service men who attacked New York cabbies, and quiet old men who shot up their trailer parks because the Astros beat the Giants, who could even remember what had happened the day before? If there had to be a memory in popular American music, feelings seemed to run, let it be of the less eventful fifties.

But Bridger said he was going to record his concept album or make no more records at all. He knew his music was good enough to merit release, and he said if he couldn’t record the music he wanted he was going to just quit and go back to teaching. This was his last piece of recorded music, he would say, then he’d find himself writing sequels about the Indian vision of Americans moving west and the 1973 siege of Wounded Knee. He had been at his project so long and had dealt with it so closely that he began to identify with it. He predicted that the spiritual and philosophical impetus of any movement to turn America around would come from the Indian movement, and his favorite current book became Vine Deloria’s God Is Red. He tried to school himself to think like a mountain man, an Indian, even a coyote. Seekers of the Fleece was more than a piece of music to Bridger. It was the driving force of his life.

Finally, when Bridger premiered his work, he chose to do it at the Pub. He thought he could draw a more intimate audience there. Still, as he sat tuning his twelve-string in the cramped office, he was worried. Seekers of the Fleece was a moving piece of work but one had to concentrate to follow it. It was long and involved, and if the listener allowed his mind to wander it was easy to lose track of the narrative, for all the characters were voiced by Bridger in similar style. He uttered a more immediate worry as he listened to one of his chords. “I don’t know what I’ll do if this thing gets out of tune.”

As it happened, there were only twenty-eight people, including waitresses, to deal with. Bridger walked onstage, asked for the audience’s cooperation and attention, and for the most part received it, though one couple left soon after he began, and another necked passionately at their table from time to time. Eyes closed in concentration, Bridger recited his initial lines of poetry in a well-pitched dramatic voice, enlisting Jim Bridger in the Ashley-Henry company, then went into the theme of the album:

I want to see something no man has ever seen

Go somewhere no man has ever been

Find myself alive with every breath

So I will know life when I meet my death

As he finished that song a new couple walked in, took a corner table, and lost themselves rather loudly in their conversation. Rod Kennedy was in the audience to help select the songs Bridger would sing at the Kerrville festival, and he lifted his eyebrows over his horn-rims and glared back at the couple, but they were too entwined in each other’s fingers and emotion to notice.

Bridger’s narrative and songs carried his characters through the first weeks of the expedition, Hugh Glass’s encounter with the grizzly and then with Jim Bridger, the discovery of the Great Salt Lake, a rendezvous with the Sioux, Jim Bridger’s first night with a Cheyenne bride, the arrival of wagonloads of Mormons and other settlers. Then in a subdued voice the narrator surrendered the floor to Jim Bridger:

Back in eighteen twenty-two

I signed up with Old Henry’s crew

We were the first to find the Sioux’s

precious Yellowstone

This land was just a baby then

Most all the Indians were my friends

Before this land was filled with men

and broken bison bones

Bridger went on singing from the point of view of a Blackfoot warrior, and the work was near its end. Finally Jim Bridger was blind and near death in Kansas City, Missouri, in 1875, reflecting on the indignity of growing old and dying in a bed. His descendant sang a song that likened death to the flight of an eagle, then recited with loud finality:

Jim Bridger was a mountain man

He walked out into unknown land

Discovered our Great Salt Lake

And lived just long enough to ache

While watching freedom lose the fight

When man pretended he was right

To hate the love of freedom

Bridger repeated his theme, heaved a sigh of relief, and leaned back on his stool. The small crowd applauded warmly as he sat there perspiring, but one blonde girl put her hands together three times in boredom. Her boyfriend laughed and waved a hand at the performer, then looked back into her eyes. You couldn’t reach everybody in a bar.

I rejoined Bridger in the Pub office as the crowd filed out. Many stuck their heads in the door to say how much they had enjoyed it. Bridger grinned and nodded to their compliments, and showed me some letters he had received about his project. One was an encouraging note from a Texas congressman, and another message was from a U.S. Interior bureaucrat interested in the project, but he wanted to know how much it would cost. Interior was frighteningly short of funds, Bridger understood, but it was this letter that encouraged Bridger most. If he was unable to find a commercial producer for the album, he was going to try to summon his old group of backers into session, finance the recording himself, and distribute the albums through the National Parks Service, tying the release to the nation’s Bicentennial celebration.

Another letter was from an RCA official who said these were the best songs Bridger had written, though this title was weak, that lyric needed work. It appeared to be the most encouraging letter of the three to me, but Bridger said he was on his way to Los Angeles to demand RCA either produce the album or free him from his contract. Reading the letter again, I wondered aloud if he should go out there with such a negative outlook. Maybe RCA would like it. He might put the twentieth century to work for him.

“Sure, that’s a nice letter,” he said, taking it back. “It’s the first positive response I’ve had from them. But what I’m going to get from RCA is the vinyl shortage”—records were made from petroleum, and oil-supplying nations in the Middle East had embargoed the United States as a political protest—“and that’s what the damn thing’s all about.”

I asked if he thought he would ever find a commercial outlet for his work.

“I think so. I think there are people somewhere who would be interested in this kind of thing, and there ought to be some company, somewhere, who would realize that. I don’t know. I’ve pushed all my earnings into the middle of the pot and I’m going to say, deal. It’s option time again, and I found RCA in the phone book.”

Bridger severed his ties in California and went to the Grand Tetons for the summer, where he resumed his writing. Plans for a recording proceeded, along with talk of a film, but the financing came from his church-going, cotton-farming friends in Louisiana. He was back where he started.