THE BALLAD OF EVELYN GOOSE AND DONNA DUMBASS

RUSTY WIER WAS SECOND to no one in the dues that he had paid. He had lived in and around Austin all his life, working his way into the music spotlight for half of it. He was talented, ambitious, energetic, and stubborn, but success always seemed just beyond his grasp. Younger musicians got the breaks he needed and passed him by while he adjusted to a life spent in roadside taverns in towns he’d never seen until he passed the city limits sign. Each new gig was a breakthrough, for he had mastered the art of making music in a bar, and the next time he came to town he would be worth a little more. Some day, he thought as he smoked and drove, he would encounter the right recording scout in the right bar in the right town. Then again, maybe he never would. It was easy to imagine Rusty Wier toppling off his stool in some suburban honky-tonk with a heart attack at the age of forty-nine.

In 1973 Wier was twenty-nine years old. Son of a well-known restaurant and hotel manager, he had grown up near Manchaca, a tiny community near Austin. Wier received a set of drums at the age of ten, and he turned up his nose when the band teacher invited him to bang his drumsticks against the rubber pad provided elementary school drummers. But he never learned to read music. He was a tall, gangly youth, all elbows and knees and Adam’s apple. In high school he concentrated on football, basketball, and track, and like many Austin area youths he went to Southwest Texas State rather than the University of Texas. While in San Marcos in the early sixties, he started playing drums in a band called the Clyde Barefoot Chester Show.

But the monotony of country music bored him. He wanted to be a rock-and-roll drummer, and he got his chance when a disk jockey named Mike Lucas decided to form and promote an Austin version of the Monkees, the Wig. Lucas wanted five minimally proficient musicians who all sang well, and Wier got the job as the drummer. The Wig was a hot act in Austin during the mid-sixties—a locally produced and distributed single called “To Have Never Loved at All” topped the Austin charts in 1966, largely through the help of Lucas, and finished the year at number five. But those were the years when Roky Erickson and the Elevators were leading the rock-and-roll rebellion, and the Wig members told Lucas they were tired of playing the role of straight buffoons.

Lucas let his ungrateful charges go, and the band quickly fragmented. Wier allied himself with a group that included John Inmon and Leonard Arnold; they were joined by a versatile musician and arranger named Gary P. Nunn, whose latest assignment had been with a popular Lubbock group called the Sparkles. The Lavender Hill Express was more of a copy band than the Elevators and Conqueroo, but it had a large reputation in Austin until 1969, when Wier realized he was going to have to get out front with a guitar if he was ever going to make a name for himself. Wier traveled alone as a folksinger. At first he had a hard time of it. He was plagued by cowboys who demanded that he sing Hank Williams, and he had his first experience with a heckler in a joint called Swingers á Go-Go. A girl maintained she could sing better than he ever could, and flustered and unwise, he invited her onstage. She was terrible, and the crowd showed signs of holding Wier accountable. Finally he squeezed her arm, grinned at the crowd, and said out of the corner of his mouth, “Ma’am, we’re both gonna get in trouble if you don’t get down off this stage.”

Wier was more accomplished and confident by early 1971. He had become the most popular solo performer in town, making too much in the pizza parlors and off-campus clubs to help Eddie Wilson out when he went looking for local talent for his new place, Armadillo World Headquarters. But popular as he was, Wier badly needed a band. He had a good voice, but couldn’t carry a solo act. Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young were all the rage in those days because they had toned down the electric guitars and rediscovered vocal harmony, and later that year Wier and two of his old band fellows formed a similar trio. Layton DePenning was a songwriter blessed with a fine tenor voice, John Inmon was a songwriter and accomplished guitar player, and Rusty was a songwriter with a way of winning a crowd over. Brimming with material, Rusty, Layton, and John invaded clubs in Texas and Arkansas, courted and seduced most of the audiences, and were good enough to attract some record-scout interest. But the trio parted amicably a year later, and Wier went on his own again, this time with a band, and he soon developed a hometown Texas routine that went over well. Just being himself was his act. He laughed and grinned and kicked in the air when he finished a song, and he became the most backwoods boy in town when the Austin music taste turned country. Jerry Jeff Walker’s fabled bootmaker Charlie Dunn made Wier a pair of boots that became locally famous, and his low-crowned hat became a popular model when the craze for Stetsons took over.

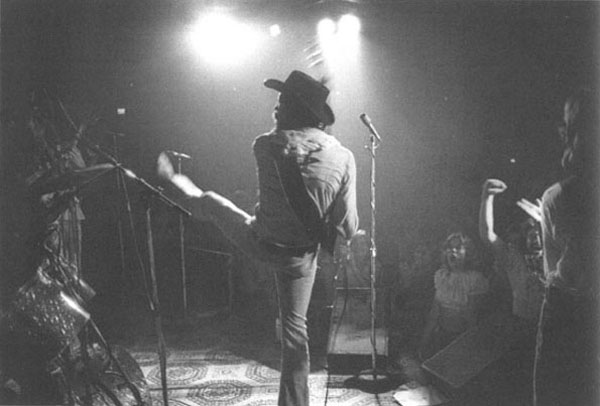

RUSTY WIER

Never Fails. Rusty Wier, in a characteristic Austin performance, has continually found the way to share his energy and involve his audience in his performance. 1972.

Wier was making money in the clubs, and some friends in the industry were trying to sell his talent to several labels, but with no success. One of those middlemen took Wier and John Inmon to Nashville to cut a demo tape. The Austin musicians were amazed by a breed of studio musicians who by some magical process converted music to a number system and played anything perfectly after four or five runs. But nothing came of the demo. Performers were arriving in Austin almost daily, and it seemed that Wier had been bypassed. Wier’s old associates were doing all right. They were members of the “Interchangeable Band,” the sidemen who jumped from band to band and would staff the studios if Austin realized its musical potential. But Wier wasn’t going to be comfortable backing anybody up. He had to make it out front, or he wasn’t going to make it.

ONE DAY IN 1973 I found Wier at the Cricket Club, which was trying to crack the country market by bringing in performers during an afternoon happy hour. Wier was all elbows and knees and Adam’s apple as he played for the crowd, and he was the sort of performer Texas club owners would love. He came across as a good old boy not too affected by all that counterculture nonsense, and he plugged the most expensive drinks in the house and promoted tobacco sales with a song called “The Cigarette Man” and with the theft of Brother Dave Gardner’s line, “If I could light a chain I’d smoke it.” He didn’t question the bar-music procedure; in fact he thrived on it. Homicidal grammar and the joys of growing up in Manchaca. The down-to-earth fellers he met on the highway construction crews. A song called “I Heard You Been Layin’ My Old Lady.” Shucks, Rusty.

The Cricket crowd wasn’t too large that afternoon, but it was enlivened by a soiled construction crew from Temple who raised an amiable uproar until the price of drinks went up. “Goddamn it, Rusty,” one said as he left. “Goodbye.”

After Wier finished he joined us at a patio table overlooking a swimming pool and the cluttered landscape of English Aire apartments. He punctuated his sentences with laughter, dipping his chin down inside his shoulders as he cackled. I asked him how he had gone from country to folk to rock and back to country.

“Well, I’m really not much of a guitar player,” Rusty said. “I found that out when I was doing all those folk gigs. I figured that country was the easiest way to get where I wanted to be. What I do is not really country, but it’s got a lot of country flavor. I appreciate straight country, but I just don’t like to play it all that much. I’ve written a lot of country songs, but I wouldn’t even think about recording a lot of them. If somebody else wanted to record them that would be all right.”

“Like ‘I Heard You Been Layin’ My Old Lady’?” I said.

Wier laughed. “No, I’d love to record that. That came about one time when I was on my way to Colorado. We were listening to a country station and three really hokey songs came on one after another, and one of the guys in the truck said ‘Rusty, why don’t you write a song called “I Heard You Been Layin’ My Old Lady”?’ I had it finished by the time we got to Denver.”

Wier talked about songwriting and his wife and small son. I asked him if being on the road all the time was hard on a marriage. His answer was a little defensive. “My wife figures it’s my business. It’s almost like I go to work at eight o’clock in the morning and get off at five. She looks at it that way. And I’m not on the road too much. We try not to go out for more than three weeks at a time.”

Was Austin music catching on outside Texas?

“I think they like rock and roll more in Colorado, but in Michigan they really like country. They like the accents and the boots and the hat—the whole trip. They’ll spot you a mile off up there.”

We talked about the Austin audiences. I had seen some artists turn their backs on crowds who wouldn’t listen.

“I started out in a beer joint,” he said. “The first gig I ever had was in a place called the Old Playboy Lounge. Nothing but cowboys, and I got off to it. I did some songs they’d like and stuck some of my stuff in there, and over the years I’ve been putting more and more of it in. I like a place like the Cricket, because I don’t want a crowd that’s dead. A lot of times when people go out to a club they’re not really in the mood to listen to the band. I can sympathize with these people, because they’re not musicians. I’m a musician. I can go out and get off to a lead guitar player, a good singer, or bass player, but they can’t take it apart like that. They take it as a whole, and if it’s not exciting you lose them. I like to get out amongst them and mix it up.”

“Do you ever get discouraged?”

“Oh, yeah, I’ve been discouraged. But the only times I get discouraged are when I’ve been playing around here a lot, and I feel like they’re gettin’ tired of me. That’s a fear anybody has at any level. But this is the only way I can do it. If you don’t start off at the top, you’ve got to make yourself take it slow, take your time, and hope for the best.”

WHEN THINGS FINALLY BROKE for Wier, they broke in a hurry. Shortly after I talked to him, he signed with Chalice Productions, a division of ABC-Dunhill. His producer imported sidemen who had played with Buffalo Springfield, Poco, Manassas, the Byrds, the Dillards, and Van Morrison, and after eight weeks in the studio, the results were surprising. Wier’s voice had echoes of Gordon Lightfoot, Tony Joe White, and Buddy Holly. Much of the material was country, but it was more of a rock album than anyone in Austin expected. Much of the credit for that went to guitarist John Inmon. He was one of the younger members of the Interchangeable Band. He wasn’t as introspective a guitarist as Leonard Arnold, and he didn’t strive for as much as Craig Hillis, but he was more inventive than either, and he covered more ground. Inmon’s guitar play, DePenning’s tenor accompaniments, and all that commercial rock talent surrounding Wier’s rough-edged voice resulted in a sound so wildly hybrid that it was almost disorienting. The title was Stoned, Slow, Rugged (1974). Nothing about it was slow.

The different sound was often the one that caught on, and the nationwide airplay surprised even Wier’s most ardent Austin followers. He began to look like more than the supporting character he had been. Wier was a visual performer; he didn’t run and hide at the mention of commerce; he was acceptable to a hard-line country audience. And he accepted beer joints for what they were.

After the album’s release I met Wier once again in the Cricket Club. The Cricket was prosperous enough that country-western happy hours were no longer a necessity, and loyal to old friends, Wier elected to premiere his album there. As we sat at a table he sent his new band through warm-up drills for that evening’s performance. They ran through “Texas Morning” and sounded better than the cut on the album. I talked to Wier at the same table overlooking the apartment swimming pool.

“I always wanted to do it with ABC-Dunhill,” he said. “They’ve got the promotion. It happened just like that, after waiting fifteen years. And I’m happy as hell so far. They said it would be out April 30th, and they hit it within three days, so I can’t complain.”

How was Los Angeles?

“Eight weeks in a motel room. I nearly climbed the walls. L.A.’s not one of my favorite places, but I wanted to do it out there. I thought I could come closer to what I wanted to do there than in Nashville. I was kind of surprised by the way the album came out though. It’s different for me. I’m going back a few years. It came out more rock and roll than I expected. But that’s fine. Everybody else is getting more country. It’s all one big cycle, I guess.”

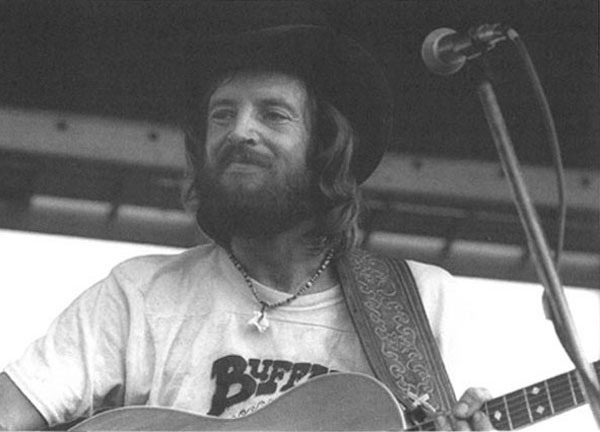

RUSTY WIER

Casual Assertion. Wier never met a live audience that he felt he could not win over. 1975.

A middle-aged man in white shoes and modern wire-rims stepped out on the patio and clapped Rusty on the shoulder.

“Hello, C. L.,” he responded.

C. L. asked Wier how his voice was holding up.

“I thought I was about to lose it. But it’s all right now. I’ve got a good doctor. He keeps me shot up with cortisone.”

“They have to shoot that into your larynx, don’t they?”

Alarmed, I looked at Wier, but he answered, “Naw, he shoots me in the ass.”

C. L. leaned against the railing and looked out at the panorama of apartments. “See those units yonder?” he said. “They’re a lot purtier than these.”

“Yeah, they look a lot better,” Wier said unenthusiastically. Glancing at me, he explained, “C. L. and I’ve sat out here many a time. We’ve watched it rain, watched the apartments burn.”

C. L. returned inside for a drink. Wier said, “You know, what I really like is an outdoor concert. It’s like sittin’ on your back porch pickin’. Concerts are good, too. You’ve got more room to move around in. But I don’t mind playing places like this. Actually, what you’re doing is magnifying your personality, trying to project a feeling that you’re like them, let’s all drink a beer and have a good time. You’ve got to fight ’em on their own ground. I’ve been there. I was a redneck myself for a long time.”

A typical Wier crowd packed the Cricket that night—rowdy, profane, prone more to ratted hair and white patent loafers than boots and straw Stetsons, used to getting what they wanted from Wier. He slouched in, calling many of them by name, pausing to shake their hands, making them feel at home. He tuned his guitar with his back to the audience then DePenning came onstage, and Wier turned around and said, “Hi, how y’all doin’? The rest of the band’s gonna be up here in a minute. In the meantime we figured we’d just pick a little, so get your cigarette and drink or whatever it is in front of you, and let’s get this show on the road.”

Wier was at his calculating best that night. He began with a straight country tune called “The Lonesome Highway Blues,” then tilted his audience in the other direction with a song that extolled the merits of smoking dope much in same country-boy manner as Terry Southern’s short story, “Red Dirt Marijuana.” Reminding them he was on their side, he railed in their behalf against snobbish Yankees: “You ever go someplace where they make fun of the way you talk? The farther you get away from Texas, the more it happens. And you get to worryin’ about it; you become self-conscious, and you train yourself to enunciate. That way you’ll be acceptable company. Only trouble is, you wind up soundin’ like a faggot.”

He played some of their country requests, but before they knew what was happening he had them squirming in their seats to rather loud rock and roll, and when he wanted them to listen to a song off the album he quieted them down with an entertaining story: “Have you ever woke up on a Sunday morning and said, ‘Man alive, who is that? Where’d she come from? What have I done now?’ That’s what this song is about. It’s off my new album, which oughta be in the stores any day now.”

Still feelin’ tight I remember last night

Just like I was sittin’ there

Tall, dark, and slinky, wearin’ long black shiny hair

Well I’d like to say she’s that pretty today

but I finally got her in the light

It’s just a stoned, slow, rugged Sunday mornin’

after a good-time Saturday night

(“Stoned, Slow, Rugged”)

The crowd loved him; he spoke their language. But they didn’t know how well he spoke it. Just a few feet away, in the darkest of corners, was a representative sampling of the audience. A tall, dark-haired man in his early thirties looked at me with a glint of recognition in his eyes but failed to place me. However, I placed him. A recent graduate of the University of Texas business school, he had a wife and family, a mortgaged home, and a ranking midway up the ladder of an automotive sales department. He valued those assets, but he was a man torn between security and infidelity. Nothing so risky as an affair, now, just an occasional stray piece. When I knew him, he told his wife that he had to spend his evenings in the library, and apparently she never checked into the business school library hours, for every night he turned into a hunter of secretaries, topless dancers, beauticians, and hippie girls, for he figured they had to be ever so much easier.

With him this night was a platinum blonde with long legs and a pointed bra; she cooed a lot while he stared at the blue lights on the Cricket’s ceiling. They had arrived separately, the car salesman leading a man who looked like one of C. L.’s fellow contractors, the blonde leading a shy, dumpy woman who jumped when Wier said “shitfire” onstage.

“This is Evelyn,” the blonde said to the older man, whom the car salesman introduced as Everitt.

“Evelyn?” Everitt said, nodding politely.

“Yeah,” said the blonde with a wise-acre giggle. “Evelyn Goose.”

After drinks arrived, the car salesman and the blonde fell into a long embrace, tongues thrusting wildly, while Everitt drummed his fingers on a glass of Scotch and ventured, “Well, ah, Evelyn, are you new to Austin?”

“No, I’ve been here a long time!”

Driven back by Evelyn’s spooked response, Everitt attacked his drink. “Do you come here often?” Evelyn ventured, looking over her shoulder at Wier, who was singing Dave Dudley’s truck-driving classic, “Six Days on the Road.”

“Oh, no,” Everitt said. “This is the first time I’ve ever been here.”

Cheeks flushed by the long kiss, the blonde turned to Everitt and attacked him coyly. “Everitt, you’re telling a lie. I’ve seen you here before, that time you brought that secretary from the office, what’s her name? Donna Dumbass?” Everitt drank in abashment.

“He raises hell and dances every night,” the blonde told Evelyn. “But sometimes he’s not too careful about the company he keeps. I think it’s called lack of couth.”

“What the hell’s wrong with the company I keep?”

“I saw you the other night with that Lester guy. He’s queer.”

“Well, he never queered me.”

“He was touchin’ you, and you was enjoyin’ it.”

“We were talking business,” Everitt said in disgust. “He needed a damn floor.”

They fell into a drinking hush and aimed their chairs toward Wier, who was singing one of the crowd’s favorites.

Well Joe, I thought we’d just sit down and drink a beer

I know you’re wonderin’ why I called and asked you here

It’s around the town that you’ve been seein’ Sue

So I called you here to ask you if it was true

I heard you been layin’ my old lady

Time must be gettin’ hard everywhere

I hear you been layin’ my old lady