THE QUOTA ON SINGING TEXAS JEWS

I HAD GROWN TIRED of talking to musicians. They didn’t have any more answers to the world’s questions than I did, and they were as reclusive as snakes. They had either just moved or they had an unlisted phone number or, if one pried that number from a sympathetic intermediary, the number had been disconnected or changed. The only alternative to all that was to attend one of their performances, wait until after the final set, and hog-tie them as they stepped off the stage. The pleasant exception seemed to be Kinky Friedman.

Friedman was a University of Texas graduate and former Peace Corpsman who boasted that he introduced the Frisbee to the island of Borneo, and while working at his family’s camp for children in the Hill Country, he learned he could make youngsters laugh when he sang. He directed his aim at an older audience and tried to sell himself in Los Angeles. He failed and went to Nashville, where he attracted the attention of Tompall Glaser, who produced his album and sold it to Vanguard in New York. When Friedman came to Austin he stayed in his family’s home, and his father, a university psychology professor and speech therapist, was listed in the directory.

“Ah, yes,” Dr. Friedman said when I called. “He’s in New York now, negotiating for a new contract. A lot of money and lawyers involved. Are you going to the KPFT benefit in Houston?”

“Hm. I hadn’t planned on it.”

Houston always struck me as a humid, excessively redneck Los Angeles. But I made the three-hour drive in order to catch up with Kinky. Houston’s KPFT was an FM station with a colorful history. It originally made its impression when it became a public affairs station with a left-wing viewpoint, and for its trouble got bombed. Lately it had pioneered a format, considerably more rock-oriented than that of KOKE, that was the radio talk of Texas. The station had to survive through listener subscriptions, but as the benefit suggested, it wasn’t making it. Trying to raise money, the station managers had enlisted most of the big-name Austin acts, as well as Commander Cody and Jimmy Buffett, and lumped them all under the heading Cosmic Cowboys, which infuriated Michael Murphey, who had coined the term, for it coerced him into being there. The young, newly elected mayor of Houston, Fred Hofheinz, had purchased a large block of tickets for the show, which supposedly meant the Houston establishment was making overtures to the counterculture. From the look of the crowd in the Pavilion, which was an overblown basketball court, it meant nothing of the sort. The concert-goers were uniformly young, long-haired, and hip to rock-and-roll country. It was time to smoke dope and boogie, even if it was in the middle of a sad Willie Nelson song.

Jerry Jeff and his band had already played and caught a plane to Phoenix. Glumly I listened to Buffett, Asleep at the Wheel, and a folksinger who said, “I’m sorry I’m not as much of a Cosmic Cowboy as the others.” There was more than a trace of resentment in his remark, an air of indignation that the musicians on the bill hailed from Austin, not from Houston. Houston was by-God Texas and proud of it, and its only rival for leadership in most Texas departments was Dallas. A disk jockey identified himself as Rockin’ Bobby Aiken and said, “We are a listener-supported station. No ads. We are asking four thousand people to subscribe at thirty dollars a year. But we only have twenty-four hundred subscribers. Now there’s six thousand people here, and simple subtraction indicates that some of you people are falling down on the job.”

The Austin audience amazed me. They would pile in cars and drive all over the state to see the same performers they had seen in Austin the week before, and the Houston concert was no exception. A whoop went up every time somebody mentioned Austin, and the visitors were dressed in pioneering get-up in order to pull rank on the directionless Houston freaks. Just after Rockin’ Bobby finished his spiel, one of the Austinites, dressed in a straw cowboy hat and Lone Star beer T-shirt, abruptly vomited on the girl next to me, wiped his chin, and staggered toward the area normally reserved for the basketball bench.

“God,” the girl said. “God.”

All I really knew about Friedman was that he was marginally famous in places other than Austin, and he pissed off a lot of people. The only cut I’d heard off his album was “Ride ’em Jewboy.” It sounded to me like he was mourning the Holocaust, but it made some people angry.

While ponies, all the dreams were broken

rounded up and made to move along

The loneliness which can’t be spoken

just swings a rope and rides inside a song

Dead limbs play with ringless fingers

a melody which burns you deep inside

Ah, how the song becomes the singers

May peace be with you as you ride

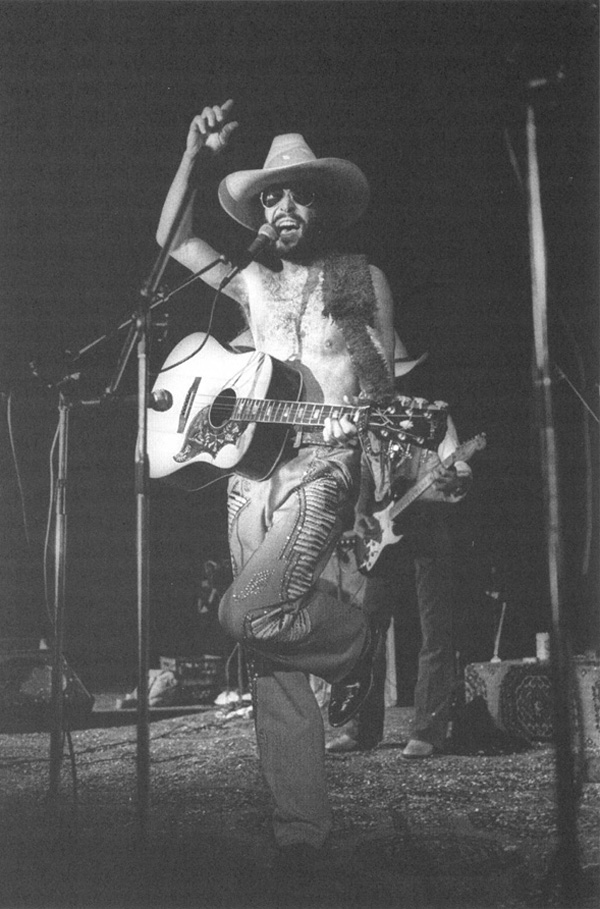

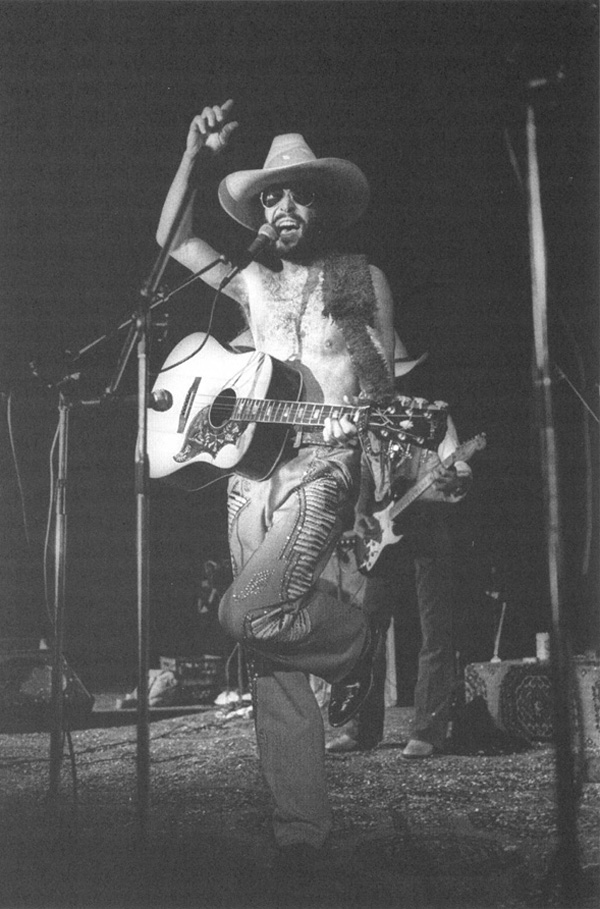

KINKY FRIEDMAN

Irreverence Bordering on Insult. Kinky Friedman’s lyrics once made Buffy Sainte-Marie explode in anger and indignation on stage. Kinky brought New York sensibility to Austin, though he grew up in Houston and Kerrville. 1977.

Billy Joe Shaver came out and said, “Hi, I’m a songwriter,” then sang his song about his good Christian raising and eighth-grade education. Shaver was too country for that crowd. They were stingy with their applause, and he abruptly left the stage, though his band hung around. Jim Franklin, who had come down from Austin to emcee the benefit, waltzed onstage in costume and introduced Friedman. “His Jewboys couldn’t make it tonight,” Franklin said, “so we lined up a good Christian band to back him up.”

Friedman didn’t look much like the Lenny Bruce of country music. His hair was short, he wore sunshades and a flat-brimmed western hat, and he smoked a cigar. He looked more like a young Groucho Marx. Friedman sang two or three songs in a mock country voice, and he tried once to alienate the audience, but it didn’t work. He tapped his cigar like Groucho and said with an exaggerated drawl, “What do you get when you cross a prostitute and a leprechaun?” Almost as if there were a censor in the sound booth, the microphone went off and Kinky lost his punch line.

“Who is that?” a girl near me said.

“Kinky Friedman,” her boyfriend said with a yawn.

Friedman caught a plane to New York, and I didn’t get away from Houston till nearly two in the morning. When I woke up I went to find his record, Sold American. The first song that got my attention was an assault on feminism:

Early in the morning you’re out on the street

passing out pamphlets to everyone you meet

You gave up your Maidenform for Lent

and now the front of your dress has an air-scoop vent

Every great man who’s ever come along

has had a little woman telling him he’s wrong

Eve told Adam, here’s an apple you boss

and Delilah defoliated Samson’s moss

Get your biscuits in the oven and your buns in the bed

That’s what I to my baby said

Woman’s liberation is a goin’ to your head

Get your biscuits in the oven and your buns in the bed

(“Get Your Biscuits in the Oven and Your Buns in the Bed”)

When Friedman sang that song in Buffalo, the stage was soon swarming with protestors, one of them weeping hysterically. What they objected to, they said, was not the song, but the pleasure Friedman derived from insulting them. Kinky didn’t help matters by telling the weeping girl, “Hey, honey, come on over here and lick my salt block.” That time the crowd almost turned against him.

The song on the record that was sure to enrage folks in Austin was “The Ballad of Charles Whitman.” The observation deck of the tower offered a grand view of the campus, the Capitol complex, and the steep hills to the west, but apparently Texans couldn’t be trusted with that kind of height. The tower served the self-destructive needs of many a despairing Austinite; suicidal students occasionally took the plunge. But the Whitman murders of 1966 were too much to comprehend. Anyone who had ever fired a rifle knew that what he did was practically impossible, even with a scope. He shot a man out of a barber’s chair several hundred yards away, and people died out in the open because others were afraid to leave their cover to help them. In his derangement, the mass murderer must have been inspired.

After it was over and the shock wore off, the topic became a conversational taboo in Austin. Passersby still glanced up at the tower and remembered, but three months after the incident, it was something that nobody talked about. Thus when Friedman started cracking jokes about it one night at a party, an Associated Press reporter—Robert Heard, who himself had been wounded by Whitman and had written his story from his hospital bed—stared an angry hole through him. When Friedman sang his song at the Armadillo, a girl broke into tears. “I just can’t believe someone would write a song like that,” she told one of Friedman’s sidemen.

Some were dyin’, some were weepin’

Some were studyin’, some were sleepin’

Some were shoutin’ “Texas number one”

Some were runnin’, some were fallin’

Some thought the revolution had begun

The doctors tore his poor brain down

but not a snitch of illness could be found

Most folks couldn’t figger just why he did it

and them that could would not admit it

There’s still a lot of Eagle Scouts around

When Friedman teamed with Jerry Lee Lewis in a concert billed as the Killer and the Kink at the Western Place in Dallas, his choice of language so offended the manager that he took his family home, then, trembling with rage, accosted Friedman in his office. “What about ‘nigger’?” Kinky shot back. “Is that an objectionable word?”

In the Austin music scene, Friedman was a marginal character. He had, after all, abandoned its charms in favor of Nashville and New York, and he was, well, pushy. Many people believed he never would have made it if he hadn’t had a brother who could sell an Alaskan husky to a camel-driver. The country instrumentation on his album was Los Angeles slick, radio programmers in Austin wouldn’t touch most of his songs, and in songwriting ability, most Austinites ranked him near the bottom of the recorded heap. He wasn’t serious about his music. Yet elsewhere, Friedman was a phenomenon. Though Vanguard failed to do much with his album, it had drawn rave reviews almost everywhere, and when he played the clubs on the West Coast, Kris Kristofferson, Allen Ginsberg, Bob Dylan, and Ken Kesey dropped by to chat. A filmed segment of one of his performances appeared on Sally Quinn’s morning show on CBS, Playboy mentioned him as a young man of note, and he was in New York trying to free himself of Vanguard so he could sign a $250,000 contract with another company. None of the other Austin performers could say that.

When I finally contacted Friedman, he gave me directions to his parents’ home and told me to come out that afternoon. Yes, he said reluctantly, I could bring a photographer. The Friedman residence was perched on a hillside in northwest, upper-middle-class Austin. His brother met me at the door and said I would find Richard out back. Inside was a thoroughly middle-class scene—opera on the stereo, Friedman’s father shuffling about in disheveled pants, his sister convalescing from the flu in front of a television set. I found the star drinking beer and sunning himself in a lawn chair on the back porch, along with his lead guitar player, Danny Finley, a slight man with short red hair and the general appearance of an adolescent, except for a cigar and forty-year-old eyes. Friedman called him Panama Red.

Friedman led me over to the porch railing and showed me a map of Texas carefully laid out with polished white rocks on the ground below. “My mother did that,” he said. “Ain’t it purty?”

He mentioned a magazine piece I had written about Austin music: “We’ve been readin’ yore magazine article,” he said. “I see you gave us part of a sentence.”

I said that was because I was working with a collaborator who thought the best way to handle Kinky Friedman was with a ball peen hammer.

“You didn’t go along with that?”

I said I didn’t know.

“Well, shake my hand and have a seat.”

I said I’d heard he was putting together a new band.

“It’s not really a new band. It’s really the driving forces of the old band, with a little more ethnic presence, I believe. We’re gonna have a coon in our band, and get rid of our Chinaman. We’re kinda keepin’ the sound under raps, strictly on the Q-T until we get this new album out. Nothing like what we’ve been doing.”

Friedman belched loudly and sneaked a glance at my friend Melinda, to judge its effect on her. I asked him about his contract negotiations.

“That’s the most exciting part of the whole musical scene. It’s not the music, it’s the machinations behind the music. At least it is for me. Ninety-eight percent of the other people involved in it seem to have a laid-back attitude. They just like their music, and if you let them they’ll jam all night, wine and T-shirts and stuff. We dig our music, but we—” He looked at Melinda, who was moving around the porch with her camera. “I’m a little bit self-conscious about being shot without my hat,” he said. “Oh, go on, I don’t give a shit.” She asked him why he was self-conscious. “I was quitting the music business a while back so I got a haircut in Mexico.”

He went on, “We’ve been trying to get off a label we were very happy to get on. Cody told us not to trust them but we signed anyway. And God, the trouble we’ve gone through—it was incredible to get off the label. And every person of any human worth in my operation has departed. All the good, innocent people are gone. That’s true of any act in the business. The ones you see, the Dinah Shores and the Jack Bennys, those are the hard ones. Their career was more important to them than anything else. You don’t hear about the ones who couldn’t stick it out. I know a girl in Austin, kind of a sad case. She’s the Janis Joplin who didn’t make it. Then again, Janis Joplin is the Janis Joplin who didn’t make it.

“Country Joe McDonald’s also on Vanguard. He can’t get off the label and he’s very bitter about it. His first problem is that he’s not Jewish. Another problem is that he doesn’t have a Jewish dad and a Jewish attorney. He’s got a laid-back attitude. The secret to it is hanging in there. I never believed we’d be off Vanguard Records, but now that we are, we’ve got a whole new lease on life.”

I asked him who had helped him get off Vanguard. He credited a New York attorney who also handled Led Zeppelin and a New York manager whose clients included the Moody Blues and John Denver. “There are a lot of people a lot groovier than John Denver,” Friedman said, “but few of them are worth as much.”

Did the contractual infighting bother him?

“It did at first, because our original negotiations with Vanguard were on a very personal level with people who were very decent and honest with us. I’m not as close to the people at the new label, and I don’t want to be. In fact this label has already had a couple of things that were pretty ugly—a lawsuit involving the Mamas and the Papas, for one thing. But what this label has is promotion cash and interest. And that’s all it takes, I think. I knew all the people intimately at Vanguard, and it didn’t do me any good.”

I asked him another question about his working past but he said, “It’d be better if we didn’t get into clinical recall. I’d just repeat what I said in Montreal.”

Kinky had me; I hadn’t kept up with his rock and roll press. I asked him what he thought of Austin music.

“I’m very ambivalent about Austin,” he replied. “There’s a Chamber of Commerce attitude around here that I don’t like a lot.”

Did he mean he liked Austin as a place to live, as opposed to a place to play?

“No, I’m not putting the music scene down. And I don’t like Austin as a place to live. When I come here I stay at my parents’ home, and until I signed this contract I was on an allowance—which was kind of tedious. You know, I’m twenty-nine years old but I come in and ask my father for five dollars.

“Austin to me is just some guy pulling a boat behind his car. It’s nice in a lot of areas, but the Armadillo and all that stuff has always left me pretty cold. We did a show out there once, and though the people who run it are nice—I like Eddie Wilson and Mike Tolleson and particularly Jim Franklin—the people who go to the Armadillo are nerds. A lot of people think it’s a very warm place, but to me it’s an airplane hangar. We were about five hundred yards from the audience for one thing, which is ridiculous, particularly if they’re not sure where you’re at. Geographical distance from the stage to the audience is murderous with an act that is satirical and sometimes downright hostile as we are. I mean, there’s a difference between us and Asleep at the Wheel.

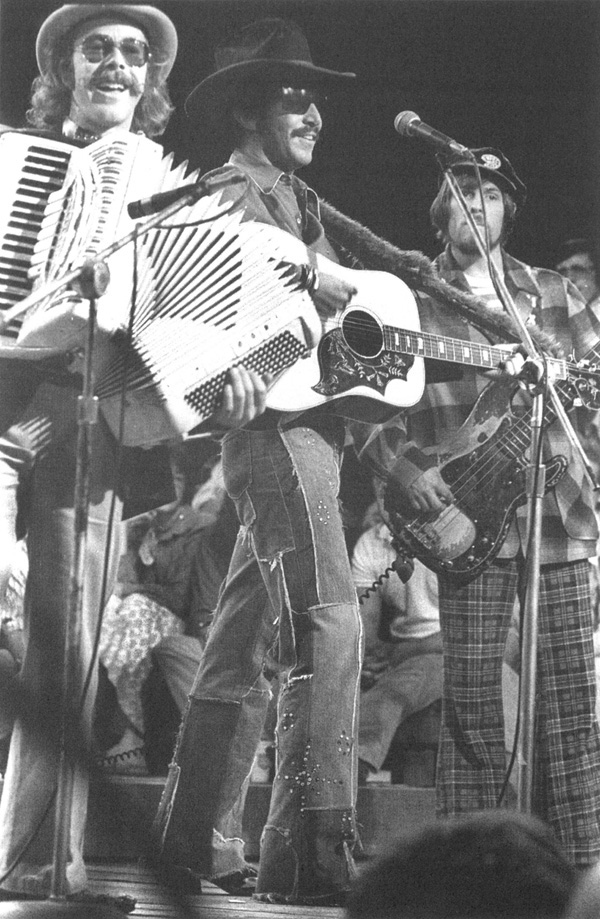

KINKY FRIEDMAN

Over the Top. The performance of Friedman and the Texas Jewboys for the first season of Austin City Limits is legendary, but it was never aired on television. Too much. 1975.

“But I’ve got to ask if the scene is really here. Something’s happening because of the interest in the press. The Washington Post called me in Nashville a while back and wanted to know about the Texas scene. But the question really is, does that mean anything? Remember a couple of years ago when Mickey Newberry and Kris Kristofferson were saying Nashville was the Paris of the thirties? Paris of the thirties, my ass, it was one big con.”

Finley interjected, “Every ten years or so they start talking about a metamorphosis in country music. There’s no such thing. After the dust has cleared, control rests in the same hands that always had it. Every time somebody says there’s a new phase in country music, invariably it doesn’t get absorbed by country, because those people reject it. It gets absorbed by pop.”

“Now if Willie Nelson can get off as a big, national, commercial pop star,” Friedman said, “with his angelic attitude intact, it’ll be very interesting to see. Somebody behind him has got to do some ball-cutting though, because you get hosed by people as you go along.

“But I wonder if it’s going to become a localized thing like Cajun music, which I suspect. I don’t really think people in Madison, Wisconsin, and Berkeley are going to get off to it. Everybody keeps talking about Waylon Jennings crossing over and becoming a pop superstar, but the only way he’ll do that is with a big TV thing or movie.

“Personally, I think all the talk about the brotherhood of country music is a lot of baloney. When Skeeter Davis pulled her stunt at the Grand Ole Opry, not one of the people who’d been singing with her for twenty years would stand up for her when they threw her off. It was a stupid thing for her to do there, talking with the Jesus trippers, but her career was just nipped in the bud, for whatever it was worth. None of those people would help her.

“I really think the best thing to say about these people in Austin is that if at any time they wanted to be a rock-and-roll star and make a lot of money, and they didn’t make it, then they just like their music. That’s the difference between me and Michael Murphey. You called him an intellectual in your article. Well, I hate intellectuals, and I am one. He maybe more of an artiste and his music may be a way of life, but I look at it as a business. If I had an old lady and a dog and a house by the lake and a child I really liked, I might be able to settle into that kind of thing.

“But what does it matter if we have two hundred or four hundred country bands in Austin? Seven years ago we had that many rock-and-roll bands, and even the best ones like Roky and the Elevators, they couldn’t get off, right? A guy like Roky, one of the original crazy guys, wound up in wig city with a patch over his middle eye. People are so goddamn fickle it’s just ridiculous. I really question the whole thing. My father was telling me I ought to play for the Temple Teens tonight; these kids would really enjoy seeing me. But I really question whether you owe anybody anything. You keep doing this shit and then one day you’re like Sonny Liston—people notice the fourteen newspapers piled up on your porch. That’s how they know you’re dead.

“It’s a question, hell, life is a question of how long you can keep putting up a front. You’re putting up a front until the day you die. You never know who’s your friend and who ain’t. And you never know what your situation with reality really is. You get to a point where you say reality is bad enough, tell me the truth. Your life could be going to hell in a handbasket, and you’re doing some show for the Temple Teens. Really, your life can be sad, depressing, a total driving bore, and you’re rushing around doing a sound track for people you despise. Jerry Jeff’s the exception to these Austin schmucks, I like Jerry Jeff. He and I were playing a radio gig down in Houston recently, and he and I were both really embarrassed by the way people were acting. Rod Stewart, Alice Cooper, and those people—if they have any intelligence, and Alice does—they develop a very strong dislike for their audiences.”

I mentioned the KPFT benefit he had played in Houston.

“I don’t want to do any more benefits,” he said, “pot prisoners or anybody. I don’t like to jam either. ‘Jewboys don’t jam’ has been our motto. I play on bills with these bands, and they say come pick, let’s jam. We never use the word ‘pick’ when we’re going onstage. A lot of bands say they’re going to pick at nine o’clock. We say we’re gonna go on. We’re more realistic, I think, about the whole damn thing.”

“The word ‘pick’,” Finley said, “indicates some kind of imbecilic joy at being able to get your hands on a guitar.”

“That’s the negative side of it,” Friedman said. “The positive side is that we take pride in a trade that’s being demeaned by a lot of hippie nerds. I’ve got a very strong feeling that you have to out-psyche your audience. Like Commander Cody, where’s his head at? He and I are friends but we’re competitors and we’re conscious of that. Everybody’s conscious of that. Even the most laid-back nerds are conscious of that unless they’ve just given up on the whole ball game. Cody takes the opposite of my view of the Armadillo. His idea is good-time rock and roll, which is fine. We’re closer to the Rolling Stones, which is mean, which isn’t for everybody.

“But I think Cody made an error. He recorded an album at the Armadillo, and Franklin did his armadillo trip on the album, and Cody played a lot of good-time rock and roll there. I don’t really view hippies as people, but no matter what you say about them, they’re people in the sense that they don’t like something that is too similar to what they are. In other words, as soon as the Austin hippies realize Cody’s band tunes onstage, and he doesn’t really have that star appeal, everybody will be more impressed with Waylon Jennings or somebody who takes more pride in his stage manner.

“Elvis Presley, for example. He may fool around backstage, but when he’s out front singing ‘Hound Dog,’ that man believes there’s nobody in the world that can touch him. You know Jerry Lee Lewis does. On the other hand, it may be that the people who really believed it were Judy Garland and Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin. Jerry Lee’s at least sharp enough not to get torn up by the fact that what he’s singing happens to be true, that he’s weaving his own handbasket to hell. When you get big, you become a joke. I started as a joke, and that’s a pretty good way to start.”

We retired inside for another beer, then occupied the Friedmans’ living room. Kinky’s numerous allergies were bothering him. He sniffed and said he usually sang through one nostril. He gazed out the window and said, “None of this fools me. This area is about as sterile as any area in Austin. Nerds live up and down this street. If you sat down in an undershirt and played a banjo in the front yard, you’d get arrested. They’re all Republican culls. But I don’t think the Armadillo scene is any cooler. Yet I’ve always told people I love Texas. I love Texas, I really do. But I can’t say anything good about it when I’m geographically here. I have to go elsewhere to appreciate it. Right now I’m digging New York.”

After a moment he said, “I’ve got to be honest with you. I don’t know where this Murphey thing got started. I’ve never seen the man perform; he’s been friendly the two times I’ve met him. I’m trying to remember why I don’t like him . . .”

“A lot of people don’t like Murphey.”

“Him, or me?”

“Well, both.”

Friedman grunted. “Probably. The Austin nerds don’t like me because I got a lot of publicity for a bogus personality. Why, I’d kill any one of them with a fork. I didn’t have to hang around Kenneth Threadgill’s joint for ten years to be cool. I lived in this city for seventeen years. I went to high school here, I did the whole trip. I didn’t suddenly become a guru with long hair. And I’ll say this. We did the whole hype without any money.

“Of course, I live here,” he said, looking out the window again. “You don’t get a lot of butt when you live at home. I’ve always lived out here, never met many girls in Austin, never been a part of the musical scene here. I had to come in from the top. Wasn’t easy. It would’ve been a lot easier had I known these people and jammed with them.”

Kinky walked us out to the car, stood on the curb a minute, and said, “Isn’t Murphey playing at Castle Creek tonight?”

“I think so.”

“I might go see him after I get through with the Temple Teens. Do you think I’d like him?”

“You might not like him but I think you’d like his music.”

“Hm,” he said. “I might do that. Let’s see, you said you lived in New Braunfels?”

“Yeah, I’m the sportswriter for the paper down there.”

He stared at me. “Is that right? Well, listen, we’re moving out to the ranch by Kerrville. Why don’t you come on up sometime?”

As we headed back toward less advantaged Austin neighborhoods, I thought I might do that. Friedman had rounded the bend toward cynicism, but perhaps in spite of himself, he was more open and engaging than most of the musicians I’d met. I thought about his album and its best cut.

Faded jaded fallin’ cowboy star

Pawn shops itchin’ for your old guitar

Where you goin’, God only knows

The sequins have all fallen from your clothes

Once you heard the Opry crowd applaud

Now you’re hangin’ out at Fourth and Broad

On the rain-whipped sidewalk remembering the time

When coffee with a friend was still a dime

Everything’s been sold American

The early times is finished

The want ads are all read

Everyone’s been sold American

Been dreamin’ dreams in a roll away bed

(“Sold American”)

Melinda was troubled. In three years she had worked and hustled herself into a career in a town where Nikon cameras seemed to outnumber handguns. She had a way of piercing the reserve of her subjects, but Friedman had rebuffed her. He was either too shy to reach, or he didn’t like her. She chewed on her lip, then brightened. At least he had asked us back. A couple of days later she ran into Willie Nelson’s daughter, Lana, who had been seeing Friedman. My photographer mentioned the invitation, and Lana said, “Yeah, he told me. Right after that he took off to Chicago.”