IRISH TEXAS

ONE NIGHT IN THE SPRING of 1972 I found myself at a free concert west of Austin on a steep slope called Hill on the Moon. The site offered an impressive view of Austin, but the ground was covered with rocks that were too small to sit on and too many to move. The free beer ran out early, and the springtime warmth impressed upon many the fact that water was as vital a human need as music. The listeners’ hands and mouths were soon sticky and colored from melting Popsicles, and their sensibilities battered by the free music. One band of teenagers imagined they were Santana, another imagined they were Peter Townsend and the Who, who would have been appalled by the comparison. Some of the concert-goers seemed to enjoy it, though. One man seized by some substance or another walked up to one of the large speakers, leaned his forehead against it, and just stood there smiling.

After the would-be Who called it quits, a man with electric hair and a New York accent walked onstage, identified himself as John Quarto, sat down in a chair, and started reciting Ginsberg-like poetry in a tremolo voice. Many of the listeners snickered, and others bristled with hostility.

“Next!” one young man said loudly. “Let’s have some music. And some wine.”

An older man with short hair and a pipe walked up to the stage and said, “Go on, man, I’m listening.”

Quarto glanced at the man, said, “Thank you, brother,” and went on with his verse. The poet was there, it turned out, because the star of the show invited him. Quarto departed in favor of a group of musicians wearing jeans and cowboy boots who plugged in their instruments and without any introduction started giving the crowd much better music than it deserved. It was rock and roll all right. The lead guitars embarked on periodic bluesy ventures and there was just enough percussion and bass to set the crowd in motion. Yet it was an unusual kind of rock and roll. The lead guitarist occasionally sat down to a pedal steel, and the leader of the band, a scratchy tenor with gleaming blond hair and a dark red beard, unstrapped his guitar and started playing a methodical, stabbing piano. It was like somebody had turned a Baptist church into a country-western honky-tonk invaded by hippies. But the longer they played, the more evident it became that this was a music in which the instruments took a back seat to the lyrics.

As the rain ruins my alibi

I’m down to telling you my red-eyed mind

It’s not that sun-bright path that calls me from my home

It’s just that fine backslider’s wine

(“Backslider’s Wine”)

I was on my feet drifting closer to the stage by then, and I looked around at my peers lost in the wilds of Austin. They were on their feet, too. The red-bearded singer left the piano, restrapped his guitar, and said, “I’d like to do another song off my new album. I wrote it with the help of the poet who was just out here.” The piece evolved from an acoustic guitar lead to Hollywood redskin music to stop-and-go rock, but it was also a cry of moral outrage:

People, people, don’t you know

the Indians ain’t got no place to go

They took old Geronimo by storm

They ripped the feathers from his uniform

Jesus told me and I believe it’s true

the red men are in the sunset too

They stole their land and they won’t give it back

then they sent Geronimo a Cadillac

(“Geronimo’s Cadillac”)

“Who are you?” somebody shouted.

The singer grinned. “My name’s Michael Murphey.”

AFTER LEAVING NORTH TEXAS STATE and Stan Alexander’s folk club, Murphey had gone to Los Angeles, married a British girl, fathered a son, auditioned to be a member of the Monkees, and signed on as a nine-to-five songwriter for Screen Gems. He hurried across town in the evenings to play backup bass in country bars, but he was a cog in the wheels of a corporation. He cranked out over four hundred songs during his stay in California—one of which George Hamilton IV took as high as number fourteen on the country charts—and his Calico Silver collection of songs about a Colorado silver-mining ghost town breathed new life in the career of Kenny Rogers. He had a home in the mountains east of town, but the Los Angeles music business got to be too much for him, so he packed his family back to Texas. But he was scarcely down and out when he arrived in Austin. He had a few press clippings commending him as one of the most gifted young lyricists in the country, an A&M recording contract, and a forthcoming album produced by Bob Johnston, who had also handled the likes of Bob Dylan, Johnny Cash, Leonard Cohen, and the Band.

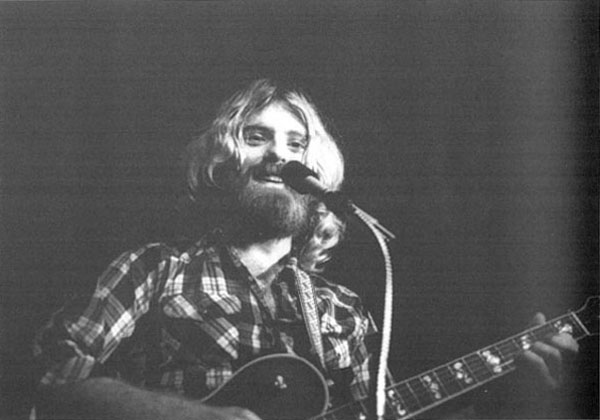

MICHAEL MARTIN MURPHEY

The Intellectual. Michael Murphey, as he was then known, coined the term “cosmic cowboys” in a song that he said was written tongue-in-cheek; his song became an anthem for the amalgam of rednecks and hippies. He fled Austin as a result. 1974.

I realized something distinctive was afoot in Austin by the end of Murphey’s concert that night at the Hill on the Moon. For two years I had been suspended between egocentric professors who kept me waiting in their outer offices and friends who smoked dope in the afternoons and schemed ways to get rich without working. I had grown stale on Austin, and I wasn’t sure I ever wanted to live there again. I got out of graduate school and drove nails for months with a foreman shouting over my shoulder in a mobile home factory in east Texas, went off on a drive to see a girl in Denver, and when that didn’t work out, came back down through New Mexico and the west Texas ranchland, seeing old friends and favorite relations. I was broke and had two degrees and still no trade, so I had to learn one. For the next few months I wrote for a small-town newspaper in east Texas, and Austin began to look better and better again. My only real contacts with the city during those weeks were the Geronimo’s Cadillac (1972) album I had found in Dallas and impatiently awaited letters from sympathetic friends. The title cut of the album had made a very small splash on the national singles-charts and the album made its impression mostly in the Southwest, but it was still a notable achievement. “Geronimo’s Cadillac” and “Backslider’s Wine” were the standout cuts, but they were matched in tone and instrumentation by other cuts similarly rooted in the tradition of country music: lyrics swimming with overturned U-Hauls in Las Cruces, trains headed toward San Antone, grapevines growing silver-green along the Natchez Trace, Wanda Lees and bordertown señoritas and Rosalees. It had all the trappings of country music, but the country steel was offset by a rock-and-roll keyboard, and the lead guitarist had a mind of his own, unlike many in Nashville. There was also a decided gospel tint to the album—a hymnal-worthy song called “The Lights of the City” and one called “Harbor for My Soul” that evoked images of a tent revival in westside Fort Worth. But Murphey’s most lyrical moments came in the soft, acoustic songs that stood out least: a boy from the country who communicated with nature, a latter-day Michelangelo waking up to his work in the city limits of Dallas. Murphey was an accomplished poet.

Rusty dawn again

Squeaking on its hinges there’s a sunrise made of tin

Rainbows on your floor belonging on your wall

And what is worse you’re not sure if you belong at all

The concentrated mind

Lags a bit behind

And lingers at the door

She won’t be there anymore

And as you realize you’ve forgotten the date

You see an unfinished portrait done back in ’58

Sort of makes you wonder if it isn’t getting late

The only problem with the album was, again, Murphey’s voice. The tenor sounded like it belonged to an Irish laborer building one of the great railroads west. It wavered and cracked in the higher ranges of the louder songs. But if he could write that well and had some business sense, he wasn’t going to have any trouble making a living in music. Bob Dylan wasn’t a threat to Frank Sinatra either. I returned to central Texas in early 1973, working in New Braunfels but spending most of my leisure time in Austin, and as my consumer’s interest in Austin music turned to writing about it, I was fascinated by Murphey. I learned he had gone to Europe while recording his album and taken a long, thoughtful look, particularly at his forebears’ Ireland. I also learned that the reason his voice sounded so bad on his album was that it was healing. He had lost even his speaking voice for several months; he jotted down lyrics on notepads and whistled new tunes to a friend with a guitar, but he silently walked the streets with an ulcer in his stomach, his career in jeopardy just as he was getting started.

Murphey was held in awe by some of his fellow Austin songwriters. He had performed his task in the Screen Gems factory so long that if someone gave him a topic he could churn out a corresponding song almost immediately, and to avoid sitting down one morning to find that he had nothing to write about but rays of light bounding off the piano keys, he had devised a system. When an appealing turn of phrase caught his attention, he wrote it out, filed it, and tabulated it to the very syllable. If people understood his system, he said proudly, they could construct a poetic, syntactically perfect sentence that made no sense at all, just by pulling the right tabs. Someday, he said, he wanted to write a book about songwriting.

He recorded at Ray Stevens’ twenty-four-track studios in Nashville, and when he went to Music City he was accompanied by his Austin sidemen and arrived with as many as two dozen of his songs. He could do that because his producer was Bob Johnston, who was very selective about the artists he worked with and had tremendous clout in recording-company offices. Johnston made a point of understanding what Murphey hoped to accomplish with each release, helped him weed out the bad cuts and thematically arrange the good ones, and the result of those sessions were meticulously produced packages like Geronimo’s Cadillac and the second album, released in 1973, called Cosmic Cowboy Souvenir.

Murphey’s voice was much stronger and steadier on the second album, and the instrumentation tended less toward honky-tonk country. One side was, I thought, the best sustained work of music any of the Austin performers had yet recorded. The four songs derived from personal experience—uncomfortable gigs in outlying clubs far from Austin, the sobering time Murphey lost his voice, a trip to the South Canadian River in northern Oklahoma. Home, after all, was just a state of mind. The title cut, “Cosmic Cowboy, Pt. 1,” had come to Murphey’s mind while he was unhappily playing the Bitter End in New York. It began on a carnival note, an ironic view of children riding the range on the wooden steeds of a merry-go-round, and it continued to amplify the cowboy theme, blending touches from “Home on the Range” and “Bury Me Not on the Lone Prairie” into a highly romanticized Texas that was still a better place to be than New York or Hollywood, particularly for musicians. The next cut went so far as to invest Austin with a vision of heaven:

Now out in the alleys of heaven

There’s a funky feeling angel strumming chords

While the preachers sit and get stoned in their Buicks

Jesus Christ drives by in his Ford

(“Alleys of Austin”)

I contacted Murphey after the second album came out, and he consented to meet me for an interview. I made the trip from New Braunfels, twiddled my thumbs for an hour, then drove back disgruntled—stood up. Murphey called the next day effusive with apologies. Heavy rains had flooded his house, and he had forgotten the interview. Could I meet him in a restaurant called the Oyster Bar Friday evening?

The Oyster Bar was an airy place with a tropical atmosphere in the building once occupied by Rod Kennedy’s Speed Museum. Jerry Jeff was on the bill a couple of doors down at Castle Creek, and Fromholz was in the restaurant with some of his friends, but for more than an hour there was no Murphey. Finally he came in wearing short sleeves, a beachcomber straw hat, and a bearded grin. “Sorry I’m late,” he said. “I bet you were freaking out.”

We moved to a larger table in another room, and Murphey said he had been at the university bookstore that afternoon, playing his guitar and promoting his album. “They called me up and asked me to do this thing, and at first I thought, no, I won’t do it, but then I thought why not? It’s kind of an ego trip not to do it, you know; a lot of artists think they’re above it. But the albums are for sale. Why not admit it? I think that’s a very legitimate kind of thing. What are you gonna do, pretend they’re not for sale? If you try to do good work, you should try a little harder to sell it. It’s when you’re not sure it’s good that you back off, I think.”

I wondered about the makeup of his audience. Murphey said Austin was a special case. In Austin he sold a lot of records to AM radio listeners and older, straight people, but elsewhere they were mostly hippies who listened to FM radio. We talked about some of the technical aspects of recording, and Murphey said he would gladly record in Austin if someone successfully installed a twenty-four-track studio. “Nashville is one of the most boring towns I’ve ever seen. There’s nothing to do there at night except make records. Nothing else. It’s really dull.”

I asked him how country music in Austin differed from that in Nashville.

“I think it’s not just Texas; it’s the Southwest. Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, Oklahoma, maybe even San Diego. I think that area really does constitute a different kind of music. For one thing, it’s founded very heavily in the tradition of the West, you know, cowboys and Indians and all the things that go with that, but not on a shallow level. I think it’s getting to be on a deeper level all the time. For example, Fromholz lives in Santa Fe some and Colorado some, but he plays down here a lot, so his music is as reflective of that environment as much as Texas. But he’s from Texas, so it all becomes a big cross-influence.

“How is it distinctive from other music? Well, there’s a blues influence and a country influence at the same time, whereas in the South it’s primarily blues. In Appalachia it’s very Anglican, based on Irish and Scottish music. But in the Southwest and Pacific Northwest you have music that’s very much founded in the tradition of the West, though it has the other influences because people from the East and South migrated there.

“It’s a very unique sound, and it becomes more distinctive as it gets out West, because when you get out there you get into the ballad tradition as well. Story-telling is a very heavy-duty trip in the Southwest. I think most of the people who grow up here are used to having relatives who tell a lot of stories, and they’re steeped in that tradition. Also, in this area there’s a back-to-the-land feeling that’s not present as much in New England or England, because there’s no land to go back to. When I went to London I found that the people there are relating less and less to American music, because so much American music is starting to talk about man’s relationship to the earth—getting back to the land and identifying more with nature. It’s not country music as much as it is the experience of living in the country. You might call it Whole Earth Catalogue music.”

Murphey never seemed to have doubts about anything in his head. “A lot of people in other places have a hard time identifying with what musicians are talking about down here,” he went on, “because people down here are on a traditional trip right now in music, and they’re going back to their roots to find meaning. They’re leaving the ashes of L.A. and going back home. The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band moves to a five-thousand-acre ranch in Colorado, and Willie Nelson leaves Nashville and comes to Austin. That has a huge influence on their music. But the Europeans have no concept of that, because the European’s idea of making it is to get out of the country and move to the city.”

I asked him to describe growing up in Dallas.

“Like most kids, until I was about sixteen years old I swallowed the trip hook, line, and sinker. The Anglo-Saxon Protestant thing—digging football, trying to make good grades, balling in the back seat, and going to church on Sunday. That’s what people did. But I swallowed it a little bit more than others. Instead of rebelling when I was a kid I went the other way. I became radically conservative, both in religion and politics. I was actually ordained to preach in the Baptist Church and did preach for a while. I was gonna be a minister, that was my goal in life, although I was playing a lot of music, too. Church music primarily.”

Well, the gospel influence was obvious in his music.

“I think it’s good music, and I think the one valid thing about that religious trip is the vibes behind it. The bad part is mixing it in with politics and logical thought. If you strip it down and recognize it as pure emotion, far out, but when you start trying to lay social and logical thought on top of it, then it starts to get weird.”

When did his religious belief begin to fade?

“I made good grades in school, and I did a lot of reading, and when I started thinking about becoming a minister I really got into it. I studied classical Greek and Latin in college, and I was translating the Bible in Greek. That’s when it began to fall apart. As anyone can tell you, education is the death of any conservative religious trip, usually. That’s why so many conservative religions have their own institutions. The Baptists have to have them, and Oral Roberts really has to have them. He’s got to keep out certain bodies of knowledge, or else he’s in trouble. He can’t expose these people to Karl Marx or Ashley Montagu. He wants them reading approved sociologies or philosophies.

“But it was reading those books. By becoming more educated I began to wake up and realize there were certain things that didn’t fit together, didn’t make sense. I don’t think I’ve ever lost my basic respect for Jesus’s teachings. I still have tremendous respect for them and even believe in a lot of them, but I don’t accept the theology that was hung on later. I mean that Baptist trip really twists what Jesus had to say around, and it was twisting my head around. I was trying as hard as I could to follow some kind of Christian trip but the harder I tried, the more I seemed to be steering away from churches and all those things. Every time I read the Bible—especially in Greek—I realized that what was being said was an extremely revolutionary, even communistic kind of philosophy. When you start saying if you see somebody in trouble give him the shirt off your back—freeze yourself rather than allow him to freeze—now what Southern Baptist is gonna do that? I never knew one that would. All the deacons used to go outside and smoke cigarettes while the sermon was on and discuss all their big used-car deals. Then they’d come in during the invitation, watch a couple of people get saved, and go home. That was all there was to it.

“But what really turned me around, more than anything else, was coming across a couple of good books by Albert Schweitzer. He’s had a tremendous influence on my songwriting, and almost every song I’ve ever written has an underlying theme of what he was trying to get across, which was a philosophy called Reverence for Life: the idea that everything that’s alive is sacred and equal. A blade of grass is equal to a human being and an amoeba is equal to John Kennedy and Richard Nixon.”

I said that wasn’t an uncommon philosophy. Murphey flicked his eyes in my direction and went on, “It’s not uncommon but it’s unusual. What Schweitzer tried to show was that the errors of all civilizations pretty much point to a lack of reverence for life. He personally felt that since his upbringing was as a Westerner he would derive his philosophy from Jesus’s teachings, but he never tried to imply that Jesus was the only trip. He very much believed that the only way you could work things out was on a person-to-person basis.

“He wrote an incredible book called The Quest of the Historical Jesus in which he covered the history of the way people interpreted Jesus’s life, and at the end he pretty much said that there are so few facts to substantiate anything Jesus said or did, that about all we can do, if we want to accept his teachings, is to accept him as a stranger. I mean, Jesus walked up to cats on the shore and said, “Follow me,” and he did all that because he had something groovy to say, not because he was trying to lay down something about being God. He was trying to organize the Jewish people and show them that they were being thwarted by an extremely gummed-up system of law. He was talking about a relationship between people.

“I accept that, man, I believe very much in what Schweitzer was saying. So much religion has been life-denying and life-negating, like the things of this world are what we must reject. Schweitzer said that the opposite is the case, that whether you believe in God or whether you believe in some great theistic blob or even if you reject God altogether, you still come down to the fact that the biological unit of the cell is here, whether God put it here or evolution put it here, it is here, and if we don’t base our morality on the fact that it is the most valuable thing there is, and build our system on that, then we don’t have a social system or civilization; it’s chaos.”

Murphey was on a roll. “Do you see any connection between the Whole Earth movement and the Jesus trippers?” I asked.

“That Jesus trip has been going on for years,” he replied. “The fact that longhairs are doing it now is just a reflection of the fashion that has crept into it. There were people like that long before anybody heard of the Beatles. I don’t attach much importance to it, except I think a few very capitalistic people like Billy Graham have gotten hold of it and tried to establish themselves as titular heads of it by pulling off big advertising campaigns.

“But I’m not really on a religious trip. I don’t even like the word religion. I do think that it’s important for people to think about the spiritual side of their lives, but only in the sense that it gives them some kind of viewpoint on where they’re going. You can derive that from almost any religion, as long as that basic reverence for life is there. It’s when you get into that trip of denying the world that you get yourself in a big bind. You can’t deny the world, man.

“But there are still a tremendous amount of life-denying people, and a lot of them live in the U.S. I mean there are plenty of life-denying generals in the U.S. Army, who are sacrificing life for what they consider some high goal, and it turns out to be jive. And you can’t blame it on materialism either. Like Alan Watts said, people think Americans are materialistic, but there’s no way they could really be materialistic because they’re so impractical. If they were really into the material world and understood the way it functions, they wouldn’t screw it up the way they do. The greatest materialists who ever lived were the Indians, because they understood how the material world worked. We don’t understand it. We sacrifice our lives for all kinds of bullshit ideals that people stick down our throats.”

He was the most self-assured man of thirty I’d ever met. Any inner struggles?

“Sure,” Murphey said, “there’s a tremendous struggle going on inside me. My biggest problem in life is trying to overcome being an American, trying to identify myself as an individual and citizen of the world, of the cosmos, not the U.S.A. I love American music, but hey, we’re on earth, we’re all in this together, and the more you travel around the more you discover that America, at this point in its history, is an extremely negative influence on the world. I’m not even sure that flower power and all that is positive either. You go over to Europe and you see Americans bumming around the highways who don’t have any jobs, they’re taking advantage of a poorer economy, they’re selling dope—so what is the impression Europeans have of these so-called hippies with supposedly high ideals? They just think they’re a lot of time-wasting bums over there ripping them off. Right now there are American beggars on the streets of Amsterdam.

“So that’s my struggle. You take so many things for granted, you assume so many things until you go overseas. Even from a freak’s point of view it blasts you. It’s different. You can’t assume everything’s gonna be groovy because you’re kinda hip and you’ve got a guitar and you can make a little money writing songs, you know, smoke dope whenever you feel like it. That doesn’t make you valuable. It just means you’re an American kid. That’s the biggest struggle I go through all the time. How far below the surface of the way I appear and act does my thinking really go? Who am I really, what do I really think? What’s my true philosophy of life? As a man where do I stand, not as a symbol or a character?”

Where did the notion of career fit into all that?

“Well, I don’t totally reject the idea of being a businessman and an artist at the same time. I think it’s possible to be both. I think artists tend to be notoriously poor businessmen, the reason being that they swallow the myth that in order to be artistic or creative one must be poor or starving. I swallowed it for years and still deal with it. Every time I make money I feel guilty. Every time I sell an album I think, am I being a capitalistic pig? You pick up those myths and accept them without thinking. I think it’s very important for anyone who’s going to get into songwriting to gain an awareness of business procedures, because if he doesn’t he’s gonna get cheated time after time after time. It’s happened to me so long that I’ve had to gain some cleverness about business, because if I didn’t my family would be broke, and I’d be in shambles and I’d never get my work out. . . . I got ripped off for five years in L. A. I ran into plenty of those guys. I’m not bitter about it, but I paid my dues.”

“Who ripped you off?”

“Oh, I ran into some people who pulled off weird publishing deals on me and never paid me. Hell, if you write a song and put all your energy and effort into it, what are you gonna do, turn right around and sell it to the next idiot? You can’t distinguish the idiots from the thieves and the nice guys without reading the contracts and understanding what they’re saying. It’s absolutely necessary to gain some business sense, because if you don’t your work may suffer. You’ve got to sell your work to disseminate it, and I think it’s very legitimate. All painters have done it, all writers have done it, all musicians have done it. It’s part of the trip, man, just as much as that wagon of gypsies rolling down the road with guitars in the back and cups in their hands. It’s part of the trip.”

Like Faulkner writing screenplays in Hollywood then retreating to Oxford to write his novels?

“Sure. You’ve just got to keep it in perspective. I’m not too fooled by what I’m doing. I know that writing pop music as a whole is a somewhat shallow occupation. It’s something I don’t want to do all my life.”

Was he saying even the best pop music was shallow?

“Well, I think that any music can have a good effect on the listener. In that sense it’s all the same. But in the sense of technical development, there’s no doubt that one of my songs is more shallow than one of Stravinsky’s symphonies. If I limit myself to writing ‘Boy from the Country’ for the rest of my life that means I’m never going to have a chance to grow and learn something else, and someday I want to write other things. You’ve got to expand.”

Murphey paused, and I tried to ask him what else he wanted to write, but this was a monologue, not a conversation. “By its nature,” he expounded, “pop music has to be somewhat limited and narrow and shallow, and no matter how much beauty and intelligence you try to inject into it, the limitations of the pop market keep you from doing as much as you’d want.”

He’d been talking primarily about writing, I noted. What about performing? What went through his mind when somebody demanded that he sing “Geronimo’s Cadillac”?

“You have to try to look at both sides of it. I mean, I put out the record. I did it, it’s my responsibility. If a drunk comes up and says, ‘Hey, play that song,’ I’ve got to live with the fact that I’m the one who made him want to hear it. So I can’t put him down like some kind of idiot, or else I’d be saying I’m an idiot myself. I always appreciate it when someone likes something I’ve done, and I always try to play what people like to hear, within the range of what I’ve done. If somebody asks me to play something that’s not my work I won’t do it.”

Why had he come to Austin?

“For a very simple reason. It’s not too big yet. It’s not so large that it just engulfs you, like L.A. or New York. And it’s a place where you can be fairly familiar with what’s going on. You know who the pickers are, but you can also relate to your neighbors who aren’t musicians. It’s a small-town kind of feeling. But I’m very much afraid that’s going to slip away.

“I don’t want to down-rap your writing or anything, but I don’t encourage the idea that there’s any music scene in Austin. There are a lot of good musicians in this town, but I don’t think anyone should ever come to Austin because there’s a scene here. Because any time you start relating to a scene, you’re in trouble. Scenes have destroyed an awful lot of places. I came here because it was a good, relaxed place to live, but you have to have your own scene together before you can make any kind of move.

“What I really think is happening is that the music business is decentralizing, and people are reaching out and finding places they like as towns, not musical happenings. I’m not pushing any big trip here. I do think there is a certain sense of community and togetherness among the musicians, if you want to call that a scene, because Austin is small. They know each other and want to help each other and there are a lot of cross-influences, but I’ve noticed even that is beginning to break down some. I know one thing. I’d hate to see people with guitars on their backs start showing up by the thousands, because they’re gonna starve.”

Murphey was breezy as a minor typhoon that night. The tapes wound on and on as he talked about the poets he admired, the metrics of songwriting, the underpaid and insecure Austin sidemen, the virtues of public television and need for public radio, the cocaine aristocracy of the New York recording industry, the rock ritual itself. “It’s not worth one overdose, and it’s not worth one person getting hurt. If that’s what rock and roll is, then let’s not have it anymore.” A couple of kids who had hitched a ride into town with Murphey finally gave up on him and went on. Finally I lost all track of the interview’s direction. By that time we had been joined by a young woman who interested me more.

Murphey was certainly the most talkative musician we had run across, but I had doubts that he would have much to say to me if I met him on the street the next day. There was a deep inner reserve in the man. There was no real interplay of ideas between us, much less personalities. I suspected that his answers would have been much the same had he been sitting alone in a recording booth, answering print-out questions fed him by a computer. Of course, I was a stranger, and he was sacrificing a weekend evening on my behalf, and the request was for an interview, not a bear hug. Still, something about Murphey troubled me. He answered questions like an academic, dissembling them into intellectual parts, tying them into a neat bundle, dropping the bundle into the satchels of students who didn’t interest him in the least. I was just out of graduate school, and I hadn’t liked it much. Murphey might have all the right answers, but he was too intense for my taste, too cerebral, too cocksure. Even when he was unsure, he was sure of the reasons.

I DIDN’T HAVE TO BE HIS PAL to like his music. One night I drove to Seguin, a German farming community northeast of San Antonio, to watch his homecoming performance at a small college called Texas Lutheran. It was a small crowd in a small, dimly lit gymnasium. Murphey and his band stood on a makeshift stage underneath a basketball goal. But it was an attentive, listening audience, the kind Murphey liked. When he had that kind of audience he talked as much as he sang, the tedious message-behind-every-song routine that folksingers use to excess. But Murphey figured he could get away with a sermon.

“I take it some of you people are Lutherans,” he said, smiling. “I can dig that. I used to be a Baptist. You know Baptists—they’re the Ku Klux Klan guys in the business suits. I did some reading and found out Southern Baptists split with the Northerners over the issue of slavery. As we all know, any good religion needs slavery.” He talked about his mother: “When I was a kid she used to tell me, ‘Mike, don’t go to UCLA. Don’t go to California. You’ll get in some weird cult out there.’ So, like she said, I went to California and got in this weird cult: country and western music.”

Murphey’s concert followed his customary form. There was a preliminary rock number or two, a relaxation toward country music, finally the slower songs he wanted them to listen to, a display of his multi-instrument capabilities. Murphey had been moved by his visit to his ancestors’ homeland of Ireland, and he studied that country’s native folk music, mastered a little Irish jig, and taught himself to play the concertina. Lowering his microphone to the level of the little instrument he explained, “My first interest is country and western, but I’m interested in folk music too—jigs and reels in particular. I understand there’s such a thing as German Texans.” Applause. “Well, I’m an Irish Texan. I finally got over to Ireland and England a few months ago, and I really believe that when a person hears the music of his people, something in him responds to it, even if he’s never lived in the old land. You don’t mind if I play this do you? I don’t play it too often; the audience is usually waiting for the Grateful Dead, and not too up for the concertina.”

Moving on to the piano, he said, “This song came out of something that happened while I was playing a club in Colorado. It was a place where rich Texans go to ski—a kind of Babylon in the snow. We were up there, hippies playing country music, when these cowboys came in. Just to prove they were cowboys, they beat up this thirteen-year-old boy, nearly beat him to death, and left him lying in the snow.”

“Rednecks,” somebody yelled.

“But then when we were driving out we saw the cowboys lying in the snow—”

Cheers erupted. “No, wait,” Murphey said testily. “That’s not the point at all. These hippies in another club down the street had found out about the kid so they went out and got two-by-fours and nearly beat the cowboys to death. It just seems to me there’s got to be a better way, and I wrote this song thinking about both the cowboys and the hippies.”

Murphey finished his set with an amalgam of “Geronimo’s Cadillac” and “Cosmic Cowboy,” and when they yelled him back onstage he stooped to play with a babe in its mother’s arms, shook a few hands, took a seat at the piano, and said, “I want you to keep singing with me. Too many times you go to a concert and you’re just an observer. I want you to be part of the act, and I want to be part of the audience. That way we can both get off.”

Murphey was more overbearing in Austin bar gigs; he was the first person I’d ever encountered who threw a fit about people smoking. He had asthma, he explained, and it was bad for his voice. And, of course, it was the wave of the future. He thought barroom crowds were generally too beery to listen. Of all that notable music on the second album, the only lines they seemed to remember were:

I just wanta be a Cosmic Cowboy

I just wanta ride and rope and hoot

I just wanta be a Cosmic Cowboy

A supernatural country-rockin’ galoot

Those were bankable lines, but they were the most regrettable ones Murphey had written. He said he had written the song tongue-in-cheek, never intending that it be taken seriously—at least at home—but increasingly his Austin appearances were populated by hooting hippies who fancied themselves goat-roping cosmic cowboys. Murphey’s music was falling prey to a fad of his own making, and he knew that could be fatal to his career. His concertina recitals became a consistent feature of his performances, and he enlisted the help of string quartets and jazz pianists to vary the impressions his listeners took home with them. His onstage political rhetoric grew harsh, and his place in the supposedly tightly-knit music community became suspect. He shed one sideman after another, and some of his recorded counterparts called him two-faced. Backstage one night at the Texas Opry House, he lamented the crowd’s response to “all that honky-tonk” of Willie Nelson, then greeted the Austin guru as he came offstage: “Willie, I love you.”

He became more and more demanding of his audiences. One night at Castle Creek, Fromholz, his pride visibly wounded, found himself playing second act for his old comrade from North Texas, delivering a few rushed songs then standing aside to say, “And now, here’s Michael Murphey.” When he came out and began to play a soft, intricate guitar piece, one of the drinkers at a stageside table went right on talking. Knuckles whitening as he gripped the neck of his guitar, Murphey stopped playing and glared dramatically. The talker was too lost in the conversation to take the hint, and Murphey snapped, “I will not play unless there’s absolute quiet. That’s just the way I am.”

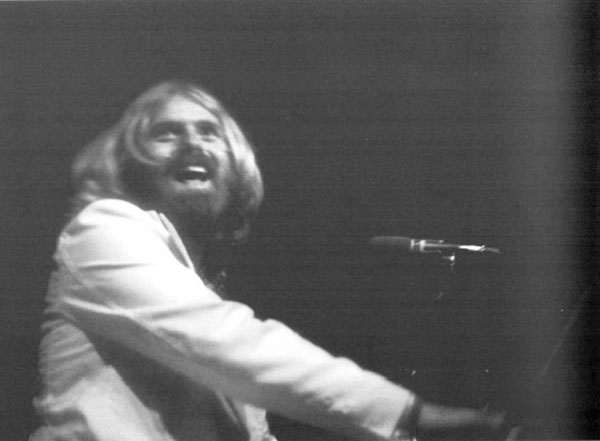

MICHAEL MARTIN MURPHEY

Seminal Concert. A Murphey performance at the Armadillo helped turn Austin’s hippies and rednecks into a convivial howling throng. 1973.

Maybe he was just in a sour mood that night. Perhaps he was courageous to voice the sentiment that goes through every musician’s mind from time to time. But after he had commandeered silence at the table, he couldn’t resist a couple of boots in the offender’s ribs. Murphey loudly granted the man permission to resume his conversation when he stepped offstage for a break, and later, when a sideman had to repair a broken guitar string, he said acidly, “You can talk now.” The problem with such an attitude was that it alienated nonmusicians who might ordinarily have been drawn to his music. The next night, when Murphey performed in resplendent white, a Castle Creek patron remarked afterward, “Jesus, I thought I was in the garden of Gethsemane.” Murphey was destined to go through life feeling he was misunderstood.

During that time, Murphey was experiencing traumas that would have left anyone irritable. After a couple of years of rocky roads his marriage had broken up, and so had his A&M record deal. He had gone through a phase of rhythm-and-blues songwriting, the rock drummer who had played on Geronimo’s Cadillac was again available, a thumping bass player who had worked with Aretha Franklin was also willing to help out, and the third album seemed a good time to break out of the country-rock rut. A&M didn’t see it that way. They rejected the album, and after a few tortuous hours in the A&M office, Murphey found Bob Johnston’s power had its limits. A&M was proud of Murphey’s previous albums, though they had never sold very well, and they insisted they just wanted their old recording artist back. Murphey contended the principle at stake was freedom of artistic expression.

Johnston demanded that A&M either release the album or release Murphey from his contract. A&M exercised the latter option, and Murphey jumped to Epic. Johnston reportedly told him a commercially successful beginning was a must with the new label, and the two sifted through his material to find the most commercial songs available. The result of that effort, a plain-vanilla package simply titled Michael Martin Murphey, had more bass, more organ; the lead guitarist Craig Hillis played more like Freddie King than Chet Atkins; and Murphey was accompanied by a female chorus that sounded practically Motown. It was closer to rhythm and blues than country and western. The use of the middle name turned out to be a launch of a new persona. He was off in a new direction, and he wasn’t going to let the music business kick him around.

Hey boy, would you like to wind up out on the street?

Tappin’ out those songs you write with your feet?

Well let me tell you, mister, my best songs came from there

The street is a hard mistress; at least it treats you fair

Hey, nobody’s going to tell me how to make my music

No matter how simple it’s got to be free

Don’t try to tell me how to make my music

It’s got to come out sounding

there’s no damn way around it

It’s going to come out sounding like you and me

(“Nobody’s Gonna Tell Me How to Play My Music”)

The album served note of a severance. Murphey’s music would never be the same again; he was moving to Colorado—later northern New Mexico—and putting distance between himself and Austin music. He was going to marry a girl from Dallas who taught children with disabilities, and they wanted to build a solar-powered home in the Rockies and administer a home for disadvantaged children there. He told a radio interviewer that he would still be around Austin, that he was moving primarily because he could no longer stand the summer heat, but he expressed to a newspaper reporter fears that the Austin music community was on the brink of big-time ruin, and he regretted any part he had played in bringing that about.

Murphey was trying to make it nationally. When he did, with a hit called “Wildfire,” (from 1975’s Blue Sky—Night Thunder) he was near the head of the class of a new breed of honey-voiced Nashville singers. (His vocal chords had healed.) But for now, his audience was still largely in Austin. He had premiered Cosmic Cowboy Souvenir at Armadillo World Headquarters, and he did the same with Michael Martin Murphey. Murphey told me considered the Armadillo an exception to the beer-splashing, glass-breaking rule of the large music hall. He liked the exuberance of an Armadillo crowd because it was mostly positive energy. But even the Armadillo was changing. The state of Texas had belatedly granted its eighteen-year-olds the right to purchase intoxicants—which only seemed proper, since so many teenagers had been drafted into Vietnam—but that gesture changed the crowds. The teenagers who flocked to the Armadillo on weekends came not so much for the music, it seemed, but for a drunken good time. One rock and roll act was as good as another, as long as there was plenty of beer. When Murphey kissed his fiancée the night of his new record’s debut and walked onstage in a Cisco Kid outfit, he gave the crowd some of the best rock and roll I had heard lately—and the Armadillo could be a great rock hall—but when he tried to settle them down for one of his softer numbers, he ran into trouble.

“Rock and roll!” somebody yelled as he tried to explain his song.

“Eat it!” someone else shouted.

“Look,” Murphey pleaded, “I know you can’t boogie too well to some of these songs, but I’d like for you to be patient and listen.”

I WAS WORKING WITH a young photographer I had known since we were teenagers. Melinda’s attractiveness and easy-going smile and manner got us through many barricades during the months we worked together, but Murphey seemed immune to her charms. Since I had established some relationship with Murphey, I told her I would request another interview and she could establish her own contact then. When I called Murphey there was not much recognition on the other end of the line, just an expectant silence. He said he would meet me again at the Oyster Bar, said goodbye, and hung up.

Two hours and a couple of shrimp dinners came and went that Friday, but no Murphey. I shrugged it off and drove back to New Braunfels, but my friend was insulted and fuming. Too many of these people treated her as a pretty girl first and a professional photographer second. Murphey’s manager finally told us a couple of Sundays later that the singer would meet us at his lakeside house that afternoon, and we made the twenty-mile drive to find Murphey had taken his fiancee to the airport and would return later that afternoon. Embarrassed, his manager said we could either go back to town or wait. My friend was determined to stick it out.

As the afternoon wore on toward evening, the wife of guitarist Craig Hillis tried to make us feel at home. We listened to Murphey’s unreleased album. Hillis drifted in as it got too dark for any photography, and so did Murphey’s dinner guests, Eddie and Jeannie Wilson. Eddie could be one of the most entertaining men I’d ever met. My mood lifted appreciably after the Wilsons arrived, but I was an intruder in Murphey’s home, interfering with a dinner party with friends. I couldn’t have been more uncomfortable if I’d been perched bare-assed on a prickly pear.

Several hours after we had arrived, Murphey came in through the kitchen, hands stuffed in his overalls pockets, and said hello to everybody. The decibel level of the conversation decreased remarkably. The manager conferred with Murphey briefly, then after his client went into his bedroom, the manager summoned me from my chair and said quietly, “It can’t be too long. He’s got to pack.” I felt like I had been granted an audience with the Pope.

Melinda sat in a corner talking for a few minutes before she realized we had gone, then asked where we were and barged through the door as the manager and other underlings watched in horror. Murphey lay on his bed with his hands clasped behind his head, glancing up in surprise. I introduced them, and she sat down in a chair, folded her arms across her chest. Murphey adjusted to another intrusion. I manufactured a couple of questions to pass the time, but it was forced conversation, dominated by the metallic neutrality of Murphey’s eyes. The conversation breathed life only when he mentioned some old Indian photographs, and explained the technical problems of turn-of-the-century photographers. Melinda corrected him on a couple of points, and he eyed her with something approaching interest. She knew more about that part of the world than he did.

I respected Murphey for his graceful turns of phrase. Our backgrounds were similar, and so were our personal philosophies. But I didn’t know Michael Murphey, and I no longer much wanted to know him. He had shown me the angry intelligence, the flickering studied gaze, but whatever was going on in that creative mind was a mystery to me. I didn’t dislike him, but I was ready to part company with him. He didn’t want to be the prophet, and I didn’t want to follow.

Yet as time went by I found myself defending Murphey to friends who were weary of his ways, and I still played his records and whistled his tunes as I went about my life. I wasn’t the only person who thought concerts at the Hill on the Moon had as much claim to the origins of the Austin music boom as Armadillo World Headquarters. I remembered the afternoon I brought boredom to that rocky cedar brake, long ago consumed by subdivision, and exchanged it for the excitement of recognizing something that was brand new. I remembered the Armadillo night I became one of those backsliding winos under the influence of good company and the Cosmic Cowboy premiere, and the solitary evening I weathered a romantic disappointment listening to his “Blessing in Disguise.” I knew that was supposed to be an adolescent response, identifying one’s personal experience with the lyrics of a pop song, but somewhere in that thicket lurked a touchstone of art.

I remembered a Christmas season afternoon in a meadow west of Austin, when Rusty Wier, Bobby Bridger, Jerry Jeff Walker, and Murphey played a benefit for an organization called Free the Slow. Only a couple of hundred people spread their blankets on the yellowed grass, but that was probably all the crowd the beneficiaries of the concert could have handled. There were the usual trappings of an outdoor concert—couples snuggling for warmth and erotic pleasure on the hillside, a girl in Barnum & Bailey facial paint juggling tennis balls, too many dogs to keep track of, a couple of hippies on horseback. But mingling with the crowd were institutionalized people of varied ages and disabilities. The runny noses and anguished grins were a source of discomfort for Wier. Bridger was uneasy because his quiet music was sandwiched between the country rockers, and the crowd seemed to drift away from him. Walker was oblivious to his surroundings as usual. But sunshaded and warmed by a Mexican serape, Murphey fairly beamed. I sat on a hillside rock drinking a beer, watching a young man with Downs syndrome. He wore a sport coat and performed a frenzied twist to one of Murphey’s rock numbers. Then Murphey sang a song that I considered his best. Working off an old blues tune, the lyrics of “Southwestern Pilgrimage” were rooted in his anxieties, restlessness, and, yes, his pretense, but in its psychological bruises and yearnings for an ideal home, the song came close, I thought, to capturing the spirit of a Texas generation. It began with a cantering guitar lead, Herb Steiner’s steel riding overhead like a whistling bell.

I’m tired of drinking your muddy water, baby,

and sleeping in your hollow log

I’m gonna take up with a stranger

and get myself a faster moving dog

Goodbye you empty closets

and my true love of seven years

I’m on a Southwestern pilgrimage

to be a frontier sonneteer

Goodbye you auctioneers and you guillotine racketeers

I’m looking for a holy man out here on the old frontier

I’m gonna take along a lady

who ain’t never seen a mountain before

I’m on a Southwestern pilgrimage