WILLIE THE LION

IF MICHAEL MURPHEY was put on this earth to play his guitar in a meadow for disadvantaged kids, Willie Nelson was born to assemble his band on a flatbed truck in the service ramp of a Ford dealership and play for used-car salesmen. That was the difference between Murphey and Willie, the difference between Willie and the others. The rest were folk and rock musicians who had drifted into country music by chance, convenience, or necessity, but Willie had been country from the outset. The prevalent strain of Austin music then was a hybrid mix of styles and traditions deemed country for lack of a better label, and while there was less suburban-bred, college-educated condescension toward Grand Ole Opry country and western in Austin than in Los Angeles, there was some of it. But Willie had grown to maturity in a rural environment. He had never gone to college and probably never gave it much thought. He had been scrapping for his nickels and dimes and saying yes sir to the rich folks almost as long as he could remember, and though he was now a rich man himself, he was still a musical representative of the hardhats and waitresses, carhops and door-to-door salesmen who were courted in the polls by Richard Nixon and George Wallace. Yet he grew his hair long and raised a beard and ran around with Leon Russell. Nelson had bridged the gap between hippies and rednecks in his own mind, and that made him the most appealing performer in town.

A searchlight played in the clouds over Austin that October evening, heralding the arrival of the ’74 Fords. A war between Israelis and Arabs had resulted in an embargo of the West by the OPEC oil cartel, and Texans were finding out about waiting in long lines for gasoline. Suddenly a Subaru was a better buy than a Torino, and Ford dealers needed all the help they could get. Somebody at the McMorris dealership in downtown Austin decided to call up an old friend and say: Willie, would you do me a favor?

Nelson got a lot of those calls in Austin, and his drummer, Paul English, who doubled as a sort of local business manager, received many more. It got the point where English would pick up his phone to dial and a voice would say, “Hello, Paul?” Willie had a reputation for finding it hard to say no to anybody, and he played more than his share of gigs that benefited some cause or organization’s pocketbook more than his. Though it was widely disregarded—to many a star and wheeler-dealer’s eventual chagrin—an old axiom in the music business suggested that you’d better be nice to old friends while you were on top, for one day soon you were liable to find your chin on their doorstep. Besides, Willie Nelson’s daddy was a Ford mechanic for twenty-six years.

Willie agreed to play in honor of the new Ford models, and word of that immediately sent traffic rushing in the direction of McMorris. There wasn’t enough room on the truckbed for all his band members, and the acoustics of the automobile service department were designed for blaring horns, not country-western music. But those were the happiest prospective customers McMorris had entertained in a while—businessmen in shirtsleeves who enthused on the fringes of the crowd, forty-five-year-old mothers who slung elbows and hips in order to deliver their requests first, young women who pirouetted in apparent ecstasy and clasped their hands in front of their bosoms as if in prayer, gazes fixed on the pot-bellied form of Willie Nelson.

One man, though, was ill at ease. He wore a lavender shirt, a white tie, and white loafers, and was pressed against the wall with a claustrophobic expression and beads of sweat on his forehead. He had the look of a man who was about to be stoned to death with crumpled beer cans. A taller man in a black sport coat stepped out of the show-room entrance, handed the perspiring man a slip of paper, and directed him toward the stage. The salesman eased along the wall, avoiding the crowd’s touch and taking the longest way around, then he plunged into the crowd and handed the slip of paper to Willie, who read it, grinned, and said that number was coming right up. The lavender-shirted man was already trying to make his escape. Before he reached safety an elbow collided with his ribs, and he jumped and looked around, raising a fist. A towering longhaired man smiled benignly. Red-faced, the man stalked back to his position along the wall, wishing midnight would hurry up before McMorris Ford got wrecked or stolen.

A friend and I were accompanied that night by a young woman whose first love was classical music, though lately she had been turning an ear toward Doc Watson and Sweetheart of the Rodeo. It was the first time she had seen Willie Nelson. We stood at the edge of the crowd, trying not to get stepped on, but then Willie’s grinning gaze fell on her. “Hm,” she said, standing on her tiptoes and moving closer. For the evening at least, I had lost her.

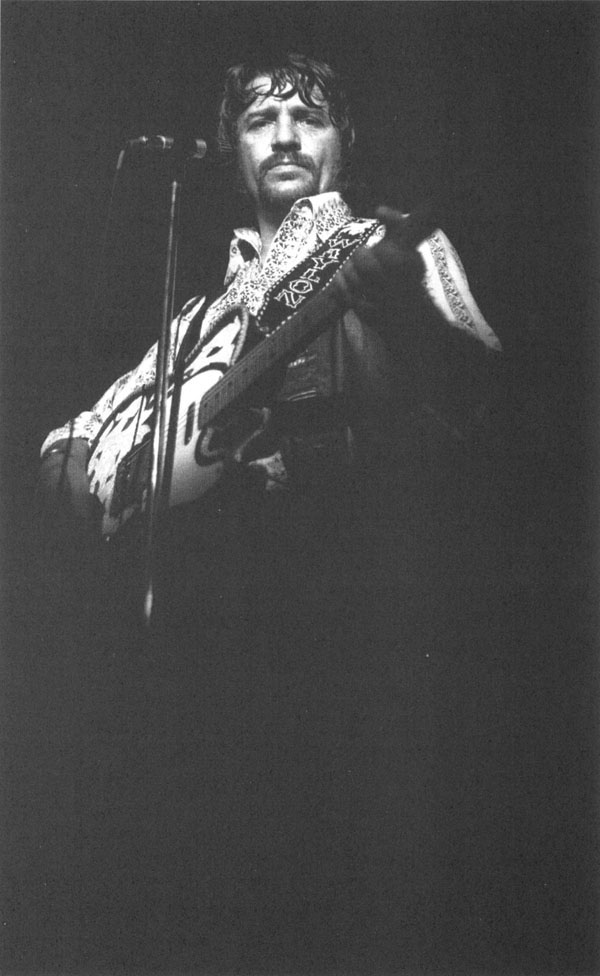

WILLIE NELSON

Stage Presence. Willie Nelson has always been the master of breaking down the barrier between performer and audience. Members of his audiences often voiced the impression that he was playing just for them. 1978.

THE WILLIE PHENOMENON began April 30, 1933, in Abbott, Texas, a by-passed community in the cotton-farming country north of Waco. Broken homes and wasted marriages and displaced children were subjects that would surface often in Nelson’s songwriting, for he learned his lessons first-hand. His parents went their separate ways when he was a small child, leaving him to be raised by his grandparents. His grandfather was a blacksmith, but music was also a part of Nelson’s inheritance. Both grandparents had mail-order music degrees. He watched them study and practice at night in the dim light of a kerosene lantern, and before his grandfather died in 1939, he taught Willie to play a few chords on a guitar. Nelson never had another music lesson, but at the age of ten he landed his first gig, playing rhythm guitar for a Bohemian polka band in West, six miles away. His grandmother reproved him, “Willie, I thought you promised me you’d never go on the road.” The makeup of that first band sounded like a country song: Willie played bass / his daddy played fiddle / sister Bobbie played piano / the football coach played trombone. One night they played for the gate and went home with eighteen cents apiece.

Willie worked at one job or another from the time he was twelve, trimming trees, laboring on the railroad, and he didn’t leave Abbott until 1950, when he joined the Air Force. After that he married a Cherokee girl and they had their first daughter, Lana. Living in Waco, they barely got by as Willie peddled vacuum cleaners, encyclopedias, and Bibles out of a broken-down car he had to park on a steep grade if he hoped to get it started again. Still playing and singing when he could, Nelson wanted his work to bear a little more relevance to his music, and he talked his way into a disk jockey’s job at a small station near San Antonio. While living in Abbott he had hung around the radio station in nearby Hillsboro just long enough to note the equipment was manufactured by RCA, and when the Pleasanton station manager asked him if he had ever done that kind of work before, Willie said sure, but he was used to working with RCA equipment. The manager put him on the air with ten minutes of news and a string of commercials, one of which he’d never forget: “Pleasanton Pharmacy, whose pharmaceutical department will accurately and precisely fill your doctor’s prescriptions.” The station manager hired the tongue-tied young announcer for forty dollars a week.

In the mid-fifties Willie hosted a music and talk show on KCNC in Fort Worth, and he played nights and weekends in a strip of bars on the Jacksboro Highway that resembled a latter-day Dodge City. Many of the customers and musicians carried a gun or at least a blade, and his favorite club was one where the management had strung chicken-wire in front of the stage to protect the musicians from beer bottles tossed from the crowd. Still a disk jockey, he moved on to Oregon and then returned to a station in Pasadena, near Houston. He was writing songs by then, scribbling them out on napkins and bus tickets—he wrote “Night Life” while driving toward a gig called the Esquire. He sold the rights for a hundred and fifty dollars. Then in 1960 Claude Gray had a top ten hit with Willie’s “Family Bible.” Living in Texas was a distinct disadvantage. That same year, Willie made the country pilgrimage to Nashville, and he was one of the lucky few. He was jamming with what bands he could when Hank Cochran heard his songs and signed him to Pamper Publishing, which was owned in part by Ray Price. Willie knew Johnny Bush, who was Ray Price’s drummer, and Price asked Willie if he knew how to play the bass. Willie lied and taught himself to play the bass in a hurry, and after that things took off for him. Faron Young recorded “Hello Walls” and it shot to the top of the charts. Price recorded “Night Life.” In 1962 Patsy Cline recorded “Crazy,” which reached number two and became a pop sensation. It was the most-played song in jukebox history. Fred Foster recorded “I Never Cared for You.” Willie recorded “The Party’s Over.” In that short span, Willie’s ability to make a living in music was assured. In addition to the Nashville artists drawn to his succinct, down-hearted lyrics, his music ranged into music fields as foreign as Perry Como, Little Anthony and the Imperials, Lawrence Welk, Stevie Wonder, and Harry James. More than seventy artists recorded “Night Life,” and when Willie heard Aretha Franklin’s version, he told friends he didn’t think he’d ever sing that song again.

The plundering of songwriters’ work is a storied facet of American cultural history, and though little could protect them from overdue bills and poor business decisions, with the coming of ASCAP and BMI they were protected and compensated fairly well. In addition to the cut songwriters got every time their lyrics sold on a record, they got royalties for radio airplay and even jukebox selections. A songwriter who contributed an unknown second side to a hit single even got an equal share of the take. Most country music fans were familiar with Ray Price’s recording of “Danny Boy,” but few except Willie’s banker remembered the flip side was “Let My Mind Wander.”

The system was prime for cheating and corruption, of course, and even an honest man could go broke in the music business. If a songwriter had hit Nashville in the early seventies with as much force as Willie had shown, he would have been an immediate star even if he sang with no teeth and a cleft palate. But Willie arrived in a decade when singers and songwriters scaled different ladders. Over several years Willie self-recorded a demo tape that he hoped would establish him as a singer. The players included session musicians named “Lightnin” Chance, “Pig” Robbins, and the great steel player Jimmy Day, who had once accompanied Hank Williams, but the point of it was to present his guitar playing, his exploring voice, and some remarkably blue-hearted lyrics. “This would be a perfect time for me to die / I’d like to take this opportunity to cry.” Willie was anxious to go out on his own, but his band leader advised him not even to try. Willie responded by stealing Price’s band: drummer Johnny Bush, fiddler Wade Ray, and Day. Willie made the mistake, he reflected later, of “buying the band a station wagon and credit card.” The band went on the road in the station wagon with a trailer hitched to the rear, but the trip west ended in misfortune. Trying to get back to Texas from California, Willie and Bush threw their suitcases on an open boxcar then huffed and puffed and watched sadly as the train outran them.

Willie’s first marriage had ended in divorce after ten years and three children, and he had run off with the wife of the disk jockey association president who would later emcee Willie’s induction into the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame. With his new wife he retreated to Fort Worth for a couple of years, took a brief look at Los Angeles, then returned to Nashville. Those were the frustrating mid-years of his career. He continued to sell his songs, and he recorded eighteen albums—two with Liberty and the rest with RCA—but neither company did much to promote them. He showed up on television with Porter Wagoner and Glen Campbell, and he once wired a five-hundred-dollar loan to his friend Roger Miller, who had driven to Hollywood in a smoking Nash Rambler. The next thing he knew Miller was a hot man on the charts with “Chug-a-Lug.” Like Pee Wee Reese risking his country-boy neck for Jackie Robinson on the first Brooklyn Dodger swing through the South, Nelson ushered Charley Pride through that same territory at a time when black churches were being bombed and blacks were confronting police dogs in Selma, but Willie said the day came when Pride sometimes forgot to speak to him.

After five years, Willie was ready to put another band together, and he wanted to move Bush up to guitar. Playing in Houston with a drummer borrowed from Skeeter Davis, he ran into an old friend from the rough-and-tumble days of Fort Worth. Paul English had owned a leather shop in Fort Worth, which allowed him enough time to play trumpet in the country bars, but in the intervening years he had become a drummer, and when he ran into Willie again he was playing the country-club circuit in Houston. “It was the kind of thing where you rode an elevator up thirteen floors then walked down to the twelfth so you could enter through the back door,” English said. “I didn’t mind it though. I was making a hundred fifty dollars a week, and I liked the people in the kitchen better anyway. “English told Nelson he could beat Skeeter Davis’s drummer any day, and Willie said, “Well, hell, I’ll just hire you then.” English was blind in one eye, his speech was slurred because of an old adenoid operation, and with a black goatee and a cape wrapped around his scarecrow frame, he looked like the devil himself, but he was the most loyal of Willie’s sidekicks. Willie and his band made some prestigious performances on major bills during those years, but it was a rough way to travel: thirty or forty straight one-nighters, jumping four or five hundred miles a night—once they played in New York, Arkansas, North Carolina, and Texas in three days.

RAY PRICE

Texas Beer-Joint Royalty. Price’s voice had a clarity that transcended the smoky Texas roadhouses where it held sway. Willie Nelson broke in as his sideman and later absconded with his band. 1980.

And Willie had other reasons to be disenchanted with Nashville. Pamper Publishing had become a multilevel conglomerate but the majority stockholders, Ray Price and Hal Smith, were no longer on speaking terms. Frank Sinatra had recorded an album of Willie’s songs but wanted to buy Pamper before he released the album. He knew how many records he sold, and how big a cut the publishers got. But Price wasn’t willing to sell to anyone he didn’t know or trust, and Hank Cochran approached Nelson and said, Willie, why don’t we buy Ray’s half of Pamper? Because of his songwriting royalties, Willie had more banking credit than a lot of Texas oilmen, so he floated the loan for a half million dollars, and the agreement was signed in Price’s den. Never a man to stay very much on top of his business affairs, Willie noticed that he was getting a lot of angry letters to pay this or that bill, so he told his partners he wanted out. Cochran and Smith assumed his share of the note, and Willie broke even on the deal, but his old partners later sold the Pamper conglomerate for two and a half million dollars. The Frank Sinatra album never came out.

By 1969 Willie had divorced again and married a pretty platinum blonde from Houston named Connie. They owned a home in Nashville and a farm in Ridgetop, about thirty miles from Nashville. But in six months Connie wrecked the car twice, and the house in Nashville burned down. When he heard about the fire Willie rushed home, wrestled from the grasp of observers who tried to stop him, and rushed inside to save his battered guitar and stash of dope. Willie and his family, Paul English and his family, and bass player Bea Spears retired to a dude ranch in Texas deserted for the winter and waited for the house to be rebuilt. Disturbed only by golfers on an adjoining course who knocked on his door occasionally in search of new balls or a nineteenth-hole beer, Willie wrote a lot during those weeks, and one song became a road anthem.

It’s been rough and rocky traveling

But I’m finally standing upright on the ground

After taking several readings

I’m surprised to find my mind’s still fairly sound

I thought Nashville was the roughest

But I know I’ve said the same about them all

We received our education

In the cities of the nation

Me and Paul

(“Me and Paul”)

Though Willie returned to his farm in Ridgetop, he was already severing his ties with official Nashville. Chet Atkins, who was the top guitar player in town and also one of the city’s most powerful businessmen, was the Nashville head of RCA, and he already worried that Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings might be the ruin of Nashville. It wasn’t their fondness for marijuana or long hair—Nashville wasn’t half as hidebound and pious as its old leaders tried to make it appear. It wasn’t their experimental take on country music. But they were going outside channels to get what they wanted. Jennings went over Atkins’ head to the New York executives of RCA, one of whom had a large photo of Willie in his office. “Hoss,” Waylon told the executive, “you already made a mistake with that one.” The official said he knew it, and gave Jennings the deal he wanted.

Willie had balked when RCA requested that he renew his contract ahead of schedule. If he didn’t, that old ploy went, the albums he’d already recorded just might not get released. Neil Rashen, a hustling New York manager with a hard-nosed reputation, heard about Willie’s hassles and volunteered to try to get him off the RCA hook, providing Willie granted him his managerial business afterward. Nelson agreed, and the matter passed into the hands of Rashen’s experienced lawyers and the executives of RCA. It is astonishing how little money he was making. Willie’s RCA contract guaranteed him just ten thousand dollars a year, and the company agreed to let him go, providing he returned fourteen hundred he had been overpaid. Free to bargain at last, Willie took his business to New York, where Atlantic offered him twenty-five thousand dollars. It was the first time Atlantic had signed a country artist.

Willie agreed to work with seasoned New York producer Jerry Wexler, and Atlantic made a New York studio available to his band, Doug Sahm and his band, and anybody else they invited. The musicians churned out thirty-three recordings, some upbeat and many slightly crazed—others serious to a fault. Write something light, the musicians advised, but Willie didn’t have a light song in mind until he sat down on the John one day and picked up an envelope that read “Another Individual Service Provided by Holiday Inn.” Instructions on how to use the sanitary napkin disposal were printed in four languages. He turned the envelope to the side that read “Preferred by Particular Women,” and scribbled:

Shotgun Willie sits around in his underwear

Bitin’ on a bullet, pullin’ out all of his hair

Shotgun Willie’s got all of his family there

(“Shotgun Willie”)

Shotgun Willie (1973) was like a dog released from its kennel for the first time in weeks, sprinting off in all directions because of the pent-up energy, and it marked a new stage in Willie’s career. When he had recorded with RCA, he had laid down a basic track and the engineers and producers took over from there. He never knew how many orchestras were going to surface on the record behind him. But he had a good measure of control over his music with Atlantic, and working with Wexler, they switched the arrangements from Ray Price to Ray Charles. It was hardly Willie’s most enduring or notable work, but it was revitalized music, the closest a recording had come to capturing the magic of his live performance. In material the album ranged from Bob Wills’s classic “Stay All Night” to Johnny Bush’s “Whiskey River” to Leon Russell’s “You Look Like the Devil,” and with that record Willie aimed the bus back to Texas.

Connie had put down a deposit on an apartment in Houston when her husband jumped to Atlantic, but he took one look at the sea of concrete and decided he’d rather move to Austin, where his sister Bobbie was already living. About the time of the Shotgun Willie release, Nelson surfaced on the Armadillo stage with his band: Bobbie at piano, English on the drums, Bea Spears on bass, and Jimmy Day on steel. Spears, a gaunt young man who had been with Nelson a long time, quickly gained a reputation as the best bass player in Austin, but Day, widely considered one of the two or three best steel players in the country, looked like he was on his last legs by the time he got to town. He mesmerized the Armadillo crowd that night with his version of “Greenfields,” but he played so poorly when he joined Commander Cody that his new band fellows were convinced he was trying to sabotage their music. As time went by, Nelson gained a new guitarist, Jody Payne, who had once been married to Sammi Smith. Willie also took on a rock-oriented harmonica player, Mickey Raphael, who always seemed to be jamming when he played with Willie. Raphael told friends that was because he never knew where Willie’s music was headed next. Raphael had been a charter member of the Interchangeable Band of Austin sidemen, but now he was part of Willie’s family.

WAYLON JENNINGS

Into His Own. Once a member of Buddy Holly’s Crickets, Jennings launched his country career in Arizona but broke out as a Texas outlaw. 1974.

The younger Austin singers and songwriters all seemed to admire Willie—even revere him—but he always stood apart from them. For one thing, he ran with a different crowd. The backstage gang which materialized at a Michael Murphey or Jerry Jeff Walker concert consisted of hippies who were very stoned and basically rock-oriented, though they wore cowboy hats and boots and drank Lone Star beer because all that was in style. The people backstage at a Nelson concert were older. Many of the women were too flabby to run around with their bellies bare, some of the men were missing a tooth or two, most all of them drank like they were trying to forget something. Though Bea Spears could have played with any rock-and-roll act, Payne had trained himself over the years to cool it with his guitar when his wife was out front singing, and Paul English would have been lost in a fast-moving rock number. Willie was a superb guitar player, but his style was simple and understated, tending more toward flamenco than rock and roll. And he wasn’t out to start a revolution as a songwriter.

Country lyricists had never set out to win many people over. They aimed their remarks at a reasonably well-defined demographic audience of working-class whites, trying to make that audience respond, “Why, that’s just the way I feel.” Merle Haggard told a Time reporter once that country songwriting was just journalism. Of course, there was honest journalism and dishonest journalism, but Haggard was right in a way. While there is a lot of flag-waving in country music, and its politics tend to the right, most of the ideology one hears is half-hearted and opportune. It is a poetry of working-class populism. Willie had been one of those people until he was thirty years old. He knew how tight-lipped and unlettered many of them were, and he didn’t flower his lyrics with flights of fancy. His songs were short and to the point, versed often in southern dialect, and they worked better, perhaps, than the lyrics of any other country songwriter in the nation. When the jukebox needle settled on the grooves of one of Willie’s sad songs, the maligned and politically manipulated wage-earners didn’t necessarily weep into their beers, but they watched the bubbles rising from the bottom of the glass, and they read Willie’s doleful turns of phrase into their own lives.

The other reason his music worked so well was his voice. Most country singers sounded like they were imitating somebody else. Couple the nasal drawls, you-alls, and ain’ts with the vapid message of most country songs, and the result could be an unwitting self-mockery. But despite all the cornball nonsense, a genuine, believable country voice sometimes came out of Nashville and endured. Jimmie Rodgers had that distinctive country voice, Hank Williams had it, Ernest Tubb had it, Hank Snow had it, Johnny Cash had it, Merle Haggard had it, and so did Willie Nelson. Willie could do more with his offbeat baritone than anybody in Austin had ever heard. When he was in the hands of the arrangers in the mid-sixties, he had had his own moments of hokum, but as he aged he learned to free his voice to wander over the lines, bending them up, down, sliding into the next note. He could have been a great jazz singer, and that’s sometimes what he sang. He also had a great affection for blues. Willie sang the blues like something inside him was in agony. Billy Joe Shaver wrote a song about Willie that likened him to a Texas blue norther, and that could be the emotional effect of Willie’s voice. It wasn’t the turbulent, barreling rush of air at the leading edge of those fronts, but the biting, chilling winds that came afterward, shuddering against the window panes at night.

THOUGH SHOTGUN WILLIE had taken a couple of rock-and-roll detours, Willie’s next Atlantic release returned to the country straight and narrow. Willie liked concept albums, and had already recorded one—Yesterday’s Wine, a man’s journey from birth to a coffin. But Atlantic promised this one lavish promotion. Willie had already recorded half the album. Its title cut, “Phases and Stages,” appeared as a single in 1972 though it went unnoticed when the flip side, “Mountain Dew,” climbed unexpectedly into the top twenty. Nelson and his band recorded a version of the album they liked in Nashville, but the album was rerecorded in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, utilizing some top session musicians. Willie returned to the time-tested country theme of divorce and proposed to tell both sides of the story.

Washin’ the dishes, scrubbin’ the floors

Carin’ for someone who don’t care anymore

Learnin’ to hate all the things that she once loved to do

Like washin’ his shirts and never complainin’

except for red stains on the collar

Ironin’ and cryin’, cryin’ and ironin’

Carin’ for someone who don’t care anymore

(“Washing the Dishes”)

The songs carried the scenario through the woman’s decision to leave in the middle of the night, her sexually defensive note instructing him to pretend she never happened. Then there were the younger sister’s observations as the woman slept through the days then finally started going out to the corner beer joint, her jeans fitting tighter than they did before. Finally the woman regained her voice and confessed that she was falling in love again, but it was the saddest song yet, full of reluctance and misgiving. The piano and violin trailed off to an image of the woman sitting alone in a loveseat, afternoon sunlight filtering through a living room curtain.

The second side began with the husband ordering drinks on a plane from Los Angeles to Houston—“Bloody Mary Morning” was one of his most enduring songs of the period. But at night the man sat on his bed his head swirling drunk with complaints that love was nowhere to be found. The next morning he awoke with the realization that the rest of his life started from there.

It’s not supposed to be that way

You’re supposed to know that I love you

But it don’t matter anyway

If I can’t be there to control you

(“It’s Not Supposed to Be That Way”)

He said later that he wrote the song one day when he was struggling to be a good parent. But the story made it into the lament of a man who’d learned nothing. His only solution to his grief was to go back to his hard-drinking, hell-raising ways.

Well, I’m wild and I’m mean

I’m creatin’ a scene, I’m goin’ crazy

Well, I’m good and I’m bad

And I’m happy and I’m sad

And I’m lazy

I’m quiet and I’m loud

And I’m gatherin’ a crowd

And I like gravy

I’m about half off the wall

But I learned it all in the Navy

(“Pick Up the Tempo”)

Whatever his ideology, in Austin Willie seemed to be able to do no wrong. He was as natural as dirt, and when he walked through a crowd he knew everybody who spoke to him. When he was introduced to someone, his brow creased in slight discomfort but then his grin lit up, and he stuck out his hand like a boy raised to be friendly. As a young man he had probably sold a lot of Bibles just on the strength of that personal look and handshake. And Willie acted like Texas was the center of the universe. He played a place like Max’s Kansas City in New York, knowing it was a record-company hype that assured him favorable treatment in the press, but he got a bigger kick out of playing an out-of-the-way beer joint in Round Rock called Big G’s, where the crowd drank and sang along for three dollars at the door. When he was inducted into the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame, he showed up at that white-tie affair in boots, faded jeans, a frayed denim jacket, and a sweat-stained straw hat, and after he played his songs and was asked for a statement, he said, “I forgot the lyrics.”

In Austin his number-one booster was Darrell Royal, who had a few boosters around the state himself. From the day in 1957 that Royal stepped on the Texas campus spouting aphorisms, he seemed to be the best coach there ever was—or at least the most popular one. His teams had turned Southwest Conference football into a predictable bore, and though his image had been tarnished by recurrent charges of racism and a book by a former player that portrayed him as an aloof man who cared only about winning, Royal was graceful even in self-defense, and he probably could have run for governor and won if he’d wanted to. But he was more interested in taking his teams to the bowl games and hanging out with country musicians. Though his latest All-American fullback had just torn the ligaments in his knee, when I interviewed Royal in the summer of 1974 I found him eager to talk about his role in Austin music.

“After I got to Austin,” Royal said, “I went to country shows at the municipal auditorium whenever I could, but I was just another spectator out in the crowd. In the course of things, though, we won a few football games, and people started noticing I was in the crowd, and the promoters started asking me to come backstage. So that’s how I became personally acquainted with the performers. It just kinda happened. I remember I used to get telegrams from Buck Owens after Texas-Oklahoma games, and I didn’t know which Owens that was until he came in one time, and they took a picture of us together that appeared in Billboard magazine.

“I met Willie the same way. The team was staying out at the Holiday Inn one night before a game, and Willie was there, too. He left a message at the desk and came up and talked. He gave me a record that I took home and listened to, and I got to know him after that. I knew the stories behind his songs and what he was trying to say in them, and I became a kicked-in-the-head Willie Nelson fan.”

Willie was popular in other establishment corners. Every organization, worthy cause, and politician in town wanted him on their side, for a Willie Nelson appearance assured a crowd. When a number of politicians staged a street-dance to cover their campaign expenses, Willie opted instead for a similar celebration a few blocks away designed to raise money for an Austin symphony orchestra. A troupe of square-dancers shuffled about in the street while professors buried their beards in watermelon, matrons in long gowns praised symphonic music and Willie Nelson between gulps of beer, and a younger woman in charge of the chocolate-cake sales told her customers, “We don’t have any forks. You’ll have to use your fingers.”

An element of hypocrisy lurked in all that, and Willie knew it. Royal retired from the University of Texas in part because an archconservative ex-governor and regent didn’t appreciate his association with a bunch of scruffy, dope-smoking musicians. Of course, that just made Willie all the more prized by the young fans who followed him about. History was etched in the lines of his face, and he was their link to their Texas past. Larry McMurtry populated his Texas novels with characters like Willie Nelson. His fictional young people were forever tossed about by the upheaval of changing times, but their steadying influence was always an old-timer who was set in the old ways but remembered what it was like to be young. In McMurtry’s book The Last Picture Show, the last thing the character Sam the Lion does is give his young friends enough money to go whoring in Mexico, while mourning the fact that he is too old to go along. Though Willie was by no means an old man, he played a similar role in the Austin community. He had known the Depression and World War II, but he was sympathetic toward those who hadn’t. If McMurtry ever wrote a novel about country musicians, he would need to consult Willie Nelson. Willie had seen it all.

WITHIN THE BUSINESS, one of Willie’s most remarkable achievements was slipping Leon Russell over on his old friends in Nashville. Russell was born at variously reported times in Lawton, Oklahoma, started playing piano at the age of three, grew up in Tulsa, migrated to Hollywood about the time John Kennedy was elected president, and according to Rolling Stone, “assembled a list of studio credits that tests the pop music trivia freak: Jackie DeShannon, Righteous Brothers, Crystals, Bobby Sox, Gary Lewis and the Playboys, Harper’s Bizarre, Glen Campbell, Jerry Lee Lewis, the Byrds, Bobby Darin, Ronnie Hawkins and the Hawks [later the Band], Herb Alpert, Frank Sinatra, Bob Lind, Dorsey Burnette, Brian Hyland, Damita Jo, the Ronettes, and Paul Revere and the Raiders.” Russell stole the show in Mad Dogs and Englishmen—which was intended as a vehicle for Joe Cocker. Russell became the prevailing American rock superstar; when the overdoses subsided, he was the one still standing. Russell knew about Armadillo World Headquarters before most people in Los Angeles—he helped Freddie King record a live blues album there in 1971—but when he appeared across the street in the Municipal Auditorium that same year, he had become the rock messiah.

His rock show was not so original as it was perfectly orchestrated—a saxophone player and rhythm-and-blues singer, a cowboy-hatted harp player with a good country-rock voice, a black girl thrusting and jiving beside his piano as Anglo males rushed forward like lemmings bound for the sea. Musicians who knew Russell insisted he was one of the nicest, shyest people one would ever meet, even if he was a tad crazy, but an entourage of security thugs followed Russell around, shoving groupies, hangers-on, and working photographers alike out of his way. Still, he played with great flair. In the midst of a rock number of almost unbearably intensity, he signaled a sideman with the petite gesture of a symphonic conductor reproving his cellist. When he neared the end of a number he raised his hand high to signal the conclusion, then played his final note with his little finger.

Few people knew that a decade earlier a sideman named Leon Russell had played on Willie Nelson’s second Liberty album. Russell had tried to make it in Nashville, and had been rejected. Willie rediscovered Russell when he heard his daughter’s Mad Dogs and Englishmen album, and he went to see one of those rock concerts in Houston. Impressed enough that he wanted to meet Russell, Nelson got an old friend to find him a gig in Albuquerque that would cover travel expenses, and he went backstage to shake Russell’s hand after his concert there. Russell told him that his favorite song was “Family Bible.” One of the most surprising alliances in American music was formed.

When Willie ushered Leon into Nashville in the spring of 1974, it was like Henry Kissinger running interference for Nixon in Peking. The studio musicians in Nashville had always respected the old graybeard, but it was a major, formal concession for Ernest Tubb, Roy Acuff, Bill Monroe, and Earl Scruggs to show up to play and party with Leon Russell. Willie even took Russell to the home of Chet Atkins. They must have laughed a lot when they went back to their hotel rooms.

Back in Austin, when Willie played the Country Dinner Playhouse, Russell sat at a table with Connie during the performance, staring straight ahead like a sphinx, and he made no acknowledgment when Willie announced his presence and the crowd pitched into a frenzy. Word got around to the people waiting for the second performance that Russell was inside, however, and during that second set Willie’s people had to surround the table to keep the people away from him. Toward the end of the set, he leaped from his chair, stepped onstage, sang a couple of duets with Willie, then sang several numbers of his own, making sure the crowd noticed the frayed cuffs of his jeans and his shiny white loafers. Leon Russell had gone country. But it was still Willie’s crowd. He played far past the legal closing hour, encore after encore, then when he tried to quit a young woman jumped onstage and attacked him with affection. Moving fast to save him, security staff hauled her away kicking and yelling.

Watching it, I wondered if the cultural synthesis he had forged was strictly an Austin phenomenon. Did this have national potential? His most avid Austin followers were hippies who happened to have rediscovered boots and cowboy hats. How was it going out where the real rednecks lived?

LEON RUSSELL

Benediction. Leon Russell was at the peak of his rock stardom when he allied himself with Willie Nelson. When he took the stage with Willie in this concert at a dinner playhouse, it was like he was anointing his friend with proper status. 1979.

Now John T. Floores was workin’ for the Ku Klux Klan

Six-foot-five, John T. was a hell of a man

He made a lot of money sellin’ sheets on the family plan

(“Shotgun Willie”)

John T. Floores lived in the country northwest of San Antonio, and he owned a so-called general store in a spot on the map called Helotes. Judging from the clutter of signs out front, he had a wealth of things to offer—sausage, real estate, insurance. But inside was just another country dance hall. Pennants hung from the ceiling, along with a few advertisements, one of which offered a “run-down beat-up shack” for sale. Beer was available at the bar, but no liquor. It was a reminder of the past.

Willie’s loyalty to old friends was renowned, and he and John T. went back a long way. According to the lore, Floores really had been a member of the Klan. One Saturday night a month Willie tried to get down to Helotes and John T.’s beer joint. I had been hearing about those Helotes gigs for several months before I finally drove over one night in November of 1973. It was the kind of crowd in Floores’s store that I had hoped to find: hippies from Austin and cedar-choppers from the sticks. As I stood by the vending machines a young woman walked by, nipples flipping under her thin blouse, and my gaze followed her through the entrance into the ladies’ room, confronted there by a stout woman with ratted black hair and heavily penciled eyebrows who glared so hard it almost knocked me back a step.

One of my company happened by with a beer in her hand and led me through the crowd of people sitting on the dance floor. I found the woman who had lured me to Helotes accepting swigs from the whiskey bottle of a booted and hatted young fellow. He bent over and whispered something in her ear, and she turned to me and said, “Do you want to go outside and smoke a joint?” The young man gave me a cold look and after that kept his whiskey to himself.

Colder and better beer was out in her car, she said, and since nobody was playing music at the moment, we walked outside beside Asleep at the Wheel’s bus, looking down the road at a Mexican cantina that was equally packed and—a fight was in progress on the parking lot—just as lively. We got a couple of beers out of the cooler but found that we had no opener for the longneck bottles. Soon we stood like beggars on the roadside, trying to find someone who would open our Pearls. A young man happened by and said, “Come over here. I’ll open the damn things for you.”

He opened the door of an Oldsmobile, snapped the lids off our bottles with the safety belt buckle, and handed them back to us. From the look on his face, the word in his mind was: helpless.

“Thanks,” I said. “Is this your car?”

“Hell, no.”

“Well, how’d you know you could do that?”

“I can just get a beer open when I need to.”

Willie had started his set by the time we got back inside and reclaimed our seats on the floor. It was the same hypnotizing music, and Willie was joined at one point by Sammi Smith, sexy as all get-out in a tight gray sweater, but there was uneasiness abroad in the land. Occupying the tables were the people who had been buying Willie Nelson’s records all along: the ones who worked hard all week, went dancing on Saturday night, showed off their labels of expensive bourbon, and got down to it. Their problem in Helotes was that the dance floor was occupied by Nelson followers from Austin, whose concert procedure was to press as close as they could to the stage, sit down, and stare up into his loving eyes. One table of whiskey-drinkers seemed particularly resentful. Their leader was a burly fellow who looked like the Marlboro man except his moustache was waxed, his head was shaved, and he wore one large earring. He appeared to have no sense of humor. He leaned over to confer with a younger, less formidable man who swallowed hard, nodded resentfully, and made his way into the crowd, where he fastened a bobby pin to the locks of a young Austin man then searched for the footing to deliver the first solid blow. The Austinite pulled the pin out of his hair, looked around at his antagonist in bewilderment, managed a sickly grin, and turned back to Willie.

“Get them hippies off the dance floor!” the customer with the earring yelled. “We wanta daince!”

Listening to the uproar, Willie washed his hands of it. “Y’all work it out,” he said. “I’d like to do a new song now. It’s called ‘Sometimes It’s Heaven, Sometimes It’s Hell.’ Sometimes I don’t even know.”

I WAS FINALLY GOING to talk to Willie. Melinda and I drove out Highway 290 past the cut-off to Jerry Jeff’s house, followed the road a few more miles, then turned off a paved cowpath that wound through thick woods, past a few farm houses, down to a low-water crossing. Melinda pulled up to a cattle guard, I opened the gate, and we drove up a gravel road toward a large, split-level ranch-style home. Willie was outside in a T-shirt and blue jeans, inspecting a couple of horses for signs of affliction while two men stood nearby. Willie waved hello as we got out of the car and invited us to come along while he robbed the nests of his chickens. He said his place used to be headquarters of a big ranch, and showed us a storage shed once reserved for wetback laborers. He said he owned forty-four acres of the surrounding land.

A couple of hundred yards down the slope from his house was a clear and fast-running Barton Creek. Connie came out and said she was going to the store. She wanted Willie to take their daughter Carlene fishing. Willie disappeared in the house for a minute and came out with a fishing pole. “I couldn’t find any hooks,” he quipped to his daughter. “I guess you’ll have to fish without them.”

He introduced us to his friends, Jay Milner and Lee Clayton. Milner was a man about Willie’s age, cowboy-hatted that day. He was a novelist and former New York journalist and later the editor of an underground paper called The Iconoclast that scandalized the Dallas establishment. He had become sort of the house writer for the family band. Clayton was about my age, squinting and quiet and thoughtful. He was also shy. When my photographer friend said she had seen him before at Castle Creek, he said, “Yeah, I remember your camera.” Blushing, he said, “That didn’t sound right, did it?”

Clayton was a Texan who had made his Austin debut on the bill of the ill-fated Dripping Springs Reunion. He had been living a nomadic existence for a couple of years, but like Willie he had migrated to Nashville and written an impressive song, “Ladies Love Outlaws,” that was recorded by Waylon Jennings. He had recorded one album of his own, and, like Willie, had tried to form his own band and gone broke. Clayton was considered one of the most promising songwriters around by the Nelson-Jennings-Shaver crowd. I never did find his album, but I liked him immediately. As we were walking up a slope toward the house, he knocked me off a copperhead I had stepped on. Willie killed the snake, and, swearing that he was going to quit walking around barefoot at night, he ushered us to chairs in a little room with a wide variety of potted plants and unobstructed views of the barnyard.

Willie told stories and rolled joints. He smoked the most powerful dope I had ever encountered. “The first day I was there a sergeant got up in my face and started shouting,” he was saying, “so I just knocked the shit out of him. That’s what we were used to doing in Abbott. They didn’t do much to me. I guess they wanted to give me a second chance. I finally decided hitting him wasn’t the answer. But I began to get tired of the military way of doing things, and an old hay-baling injury of my early youth finally got to me, so I regretfully ended my career in the United States Air Force.”

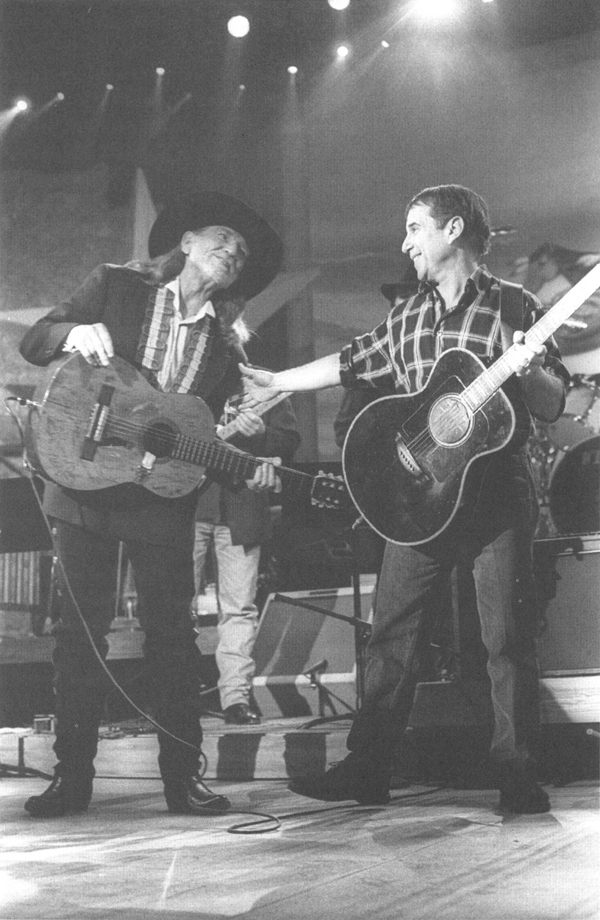

WILLIE NELSON AND PAUL SIMON

Legends. Willie and Paul Simon at Willie’s sixtieth birthday concert. 1993.

“When did you decide you wanted to make music for a living?”

“As soon as I found out I could. When I first made that eight dollars in West. Later on I’d been picking cotton and baling hay for fifteen cents a day. It wasn’t a difficult decision.” He talked about the Jacksboro Highway days in Fort Worth then said, “I went to Nashville in a ’41 Buick that I was behind two payments on. It made it to Nashville and just settled to earth, never moved again.”

My friend asked if he had any encouragement to go to Nashville.

“No, I really just went in cold, on my own.”

“Isn’t it hard to make it like that?” she asked.

“Damn near impossible,” Willie replied, glancing at Clayton.

“Nashville’s like a circle,” Clayton said, “the ones on the inside, the ones on the outside. Unless somebody on the inside notices you, you’re never gonna break in.”

Willie talked about his early days in Nashville, and I asked him about the Charley Pride episode.

He grinned and said, “A friend called me and said, ‘Man, I think you ought to book this nigger on the tour. He sings his ass off.’”

“I said, ‘You gotta be crazy. We can’t take no niggers into Dallas and Shreveport. They’d hang us.’ But I heard a couple of his records on the car radio and called Crash back and said, ‘Listen, if you can still get that nigger . . .’

“When we got to Dallas I made out the program so I’d follow him. Pride walked out and said, ‘I guess you’re probably wondering what a man with a permanent tan like myself is doing singing country music, but I like it and I hope you enjoy hearing it as much as I enjoy singing it.’ He Uncle Tommed them into a standing ovation. They were yelling for Charley Pride all through my set. The next night I said, ‘Bullshit, I’m not following him,’ so I went on before, and Hank Williams, Jr., went on after. They couldn’t boo Hank Williams.”

“Tell him about the time you kissed him onstage,” Milner said.

“That was in Shreveport or Baton Rouge, I think. We didn’t know what was going to happen there, so I really laid it on about him, and when he walked out I kissed him, kissed him on the mouth. Of course we had to move on fast to something else, but by the time they got over the shock he was already playing, and he had them hooked.”

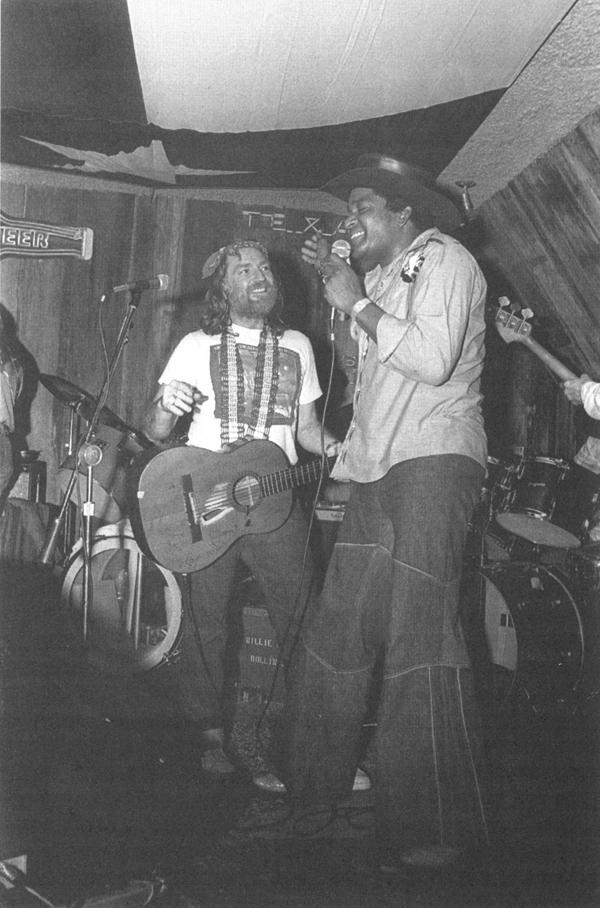

WILLIE NELSON AND CHARLEY PRIDE

Duet. Singing with Pride at the Soap Creek Saloon, Nelson had once made the way easier for the black country singer’s success in Nashville. 1975.

Clayton laughed and said, “Yeah, but later on they were looking for the guy who kissed that nigger.”

“How did you like living in Nashville?” I asked Willie.

“I liked Tennessee a lot. I’ve still got a farm down there. But I eventually just quit going to town. They have their own way of doing things there. I was just in Nashville. A lot of new blood’s coming in, younger people. They’re doing everything they can to change their image. Because places like Austin are growing, their image is starting to hurt them, and when that happens it’ll hurt their pocketbooks, so they’ll change then. It’s a hard town, there’s no doubt about it. They don’t give a shit if you pack up and leave, in fact they’d just as soon you did.”

“Are there a lot of places to perform in Nashville?

“No,” Clayton said, “it’s mostly a place for songwriters.”

“Sitting around and talking to writers in Nashville is the most depressing thing in the world,” Willie said. “There are just so many of them—and it gets to the point where it’s ‘niggers and dogs and writers, stay off the grass.’

“The thing about Nashville is that those session musicians are so good that it sounds like manufactured music. There’s no feeling to it at all. And you can’t help that when you’re playing nine hours a day every day. But they’re making so much money they can’t afford to change. The musicians know they could do better. But they make more and more money and they make good records, all right, but the trouble with them is that they’re too perfect.”

“Does that mean the reverse is true in Austin?” I said. “That the imperfections of Austin music are its virtue?”

Willie blinked and leaned forward. “I didn’t get the last part of that . . .”

“You said Nashville music is too polished. Is Austin music unpolished?”

Milner hooted. “That’s not what you said the first time around.”

Willie grinned and looked over at Clayton. “No, I’d rather think that we’re somewhere between perfect and half-perfect. The mistakes, we call that soul. I’m always building on mistakes, trying to turn them into hot licks, and that’s not always easy to do.”

Milner observed that Willie played differently in different situations, and he often played tricks on the crowd. The night before he had played “Bloody Mary Morning,” a virtual rock number, then gone straight into an agonizingly slow song, “I Still Can’t Believe You’re Gone.” “That popped their necks,” Milner said. “That’s dangerous.”

“Well, you have to catch them with their feet in the air,” Willie said. “Like kissing a nigger onstage.”

Clayton laughed again. “You’ve given us a new expression, Willie. ‘Kiss a nigger.’”

“Maybe a new song,” Willie said. “Kiss a Nigger Good Morning.”

“What about Austin?” I said. “Can the music here break out nationally?”

“I think it already has,” Willie said. “Jerry Jeff and Michael Murphey are getting a lot of national attention. There’s got to be a big rush—I can already see the songwriters coming, songs by the trunkload.”

Could Austin become another Nashville?

“Easily. As soon as the money gets down here. As soon as the recording studios get set up.”

“Won’t the money and technicians have to come from outside?”

He nodded. “Everybody’s waiting for me to do it, but I’m not ready to get that far into it yet. I would like to record here, however. But we’d have to get a good engineer and a couple of good Nashville musicians.”

Melinda asked if there were enough good musicians in Austin to make those studios work.

He nodded again. “It wouldn’t have the Nashville polish, unless you brought in a couple of hot-shots who could do it just like that, and mix them with the others, who are slower. The musicians in Austin could learn a lot from Nashville musicians. They’re good here, but what they lack is the ability to work in one unit. It would take some time, but pretty soon you’d know who the top three guitar players in Austin are.”

I looked at Clayton. “Wouldn’t that be the same thing? The circle?”

“Sure,” Willie said. “The first thing you know you’ve got the clique going again, and the top three won’t want to let the fourth one in.”

“When it really gets good,” Clayton predicted, “that’s when it’ll start going bad.”

“Well,” Willie said, “there’s nothing to stop us from setting up in Luckenbach. The organizers are gonna come in, but I think we can frustrate them. Just by making a point of never getting caught with any of the money people.”

“Will you move on if it gets too organized?” Melinda asked.

Willie’s daughter was playing the piano in another room. He gazed out at his peacocks, the manicured slope down toward Barton Creek, the woods beyond. “No,” he said. “I don’t know what could ever make me move.”