OUTLAW COUNTRY

THE PRECEDING PAGES are a meridian of my life. I was twenty-nine when they were first published; now I’m fifty-eight. A sobering thought. I was anxious to write a book, any book, but had little idea how to go about it. Apart from a few months of toil in small-town newspapers, my published output amounted to one eight-line poem in a political journal, the Texas Observer, and four articles in the newborn Texas Monthly; on three of those assignments, feeling too green as a reporter and otherwise insecure in my craft, I enlisted a collaborator. But one of those early pieces caught the eye of David Lindsey, a slender young man with a well-trimmed black beard and a yen for stylish attire. Like me, David had blue-collar roots in the west Texas oilfields. Like me, he wanted to write for a living and was working up the nerve to try it. In the meantime he was helping compile a new volume of The Handbook of Texas, and, with one wild game cookbook to his credit, he thought he might make his way as a book publisher.

In the summer of 1973 he mentioned my article on Austin music as a possible book to a pretty, dark-haired colleague named Melinda Wickman. She also was working on the Handbook as a researcher, but she was a photographer with extensive studio training and impatient talent, and she knew me. We had dated briefly when we were growing up in Wichita Falls: Sunday night church followed by Cokes at some drive-in and a round of Putt-Putt. Neither of us was fast aboard the roaring train of the 1960s. We’d been out of touch for a while when she called. I met David and Melinda for dinner at one of the Night Hawk restaurants that then passed for Austin cuisine. After a couple of hours we convinced ourselves that we had a book. David left our first meeting with his face aflame. He had forgotten his wallet, and I picked up the check.

Don Roth had become my friend in graduate school and had helped me get out the Texas Monthly piece. Don would find his profession in music—managing symphony orchestras from Hartford and Syracuse to Portland and St. Louis before settling in as director of the summer festival in Aspen—but he decided then it was in his best interest to finish his dissertation in history. With a burst of newfound confidence I forged ahead. The New Braunfels Herald-Zeitung, where I was the sports editor, was then a weekly paper. I had a sympathetic boss, and except for Friday night football I was able to cram my hours into Monday-to-Wednesday marathons; then I headed for the music venues and subculture of Austin, often arriving at the bus station, for my car was always broken down. I crashed on the sofa of Melinda, who had gotten a job taking pictures at the legislature. David had no money for advances, but he and his wife Joyce sustained me with much good conversation, food, and friendship. Heidelberg Publishers’ first office was a room fashioned from a garage in their back yard. Their collie Summer would greet me at the gate and escort me to the door.

We were a very cocky team until an item in Texas Monthly announced that Jay Milner and Chet Flippo were writing books about the Austin music scene. This was chilling news. Milner was a veteran journalist and a novelist and had hitched on as the house writer with Willie Nelson’s entourage. Flippo had been covering Texas music for Rolling Stone with great flair. Both were capable of selling their books to national publishers with much deeper pockets than Heidelberg’s. In no uncertain terms David told me that the first horse out of the gate was going to win the derby.

My working life became a blur. The duplex where I lived in New Braunfels was strewn with pencils, notepads, recording reels, interview transcripts, album covers, dirty laundry; the faucet in my kitchen dripped for months because I wouldn’t take the time to figure out how to change a gasket. David’s feel for the market proved to be correct. Milner and Flippo wrote other admirable books, but their takes on Austin music never came out. As the weeks passed and our pile of pages grew, David began to remind me of our need for a title; he had advertising deadlines to meet. I took to calling it Sing Me a Texas Song—not bad, but too quiet. At last, one afternoon I walked through the yard with the collie and rapped on David’s screen.

“I think I know what to call it,” I told him.

“All right.”

Like a conductor I waved my hand over the rough spots—I would fill in the blanks later. “Da Duh da Duh da Duh . . . of . . . Redneck Rock.”

It was a gimmick, and I paid for it. I was often asked to defend my title, for though it was offered tongue-in-cheek, it did have a confrontational edge. Claimed by the KOKE-FM radio format and endorsed by Flippo in Rolling Stone, “progressive country” was the standard generic, but even then that sounded like the wishful thinking of liberal Democrats. Though we were well into the seventies, the sixties cast a long twilight, and elsewhere the cultural dialectics seemed as stiff as iron bars. On country stations Merle Haggard fairly sneered the line, “We don’t smoke marijuana in Muskogee,” and in the movies, Easy Rider’s southern rednecks rose to hippiedom’s occasion by blowing Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper to kingdom come. In Texas, of all places, we proposed to dispense with that inane hostility and have it both ways.

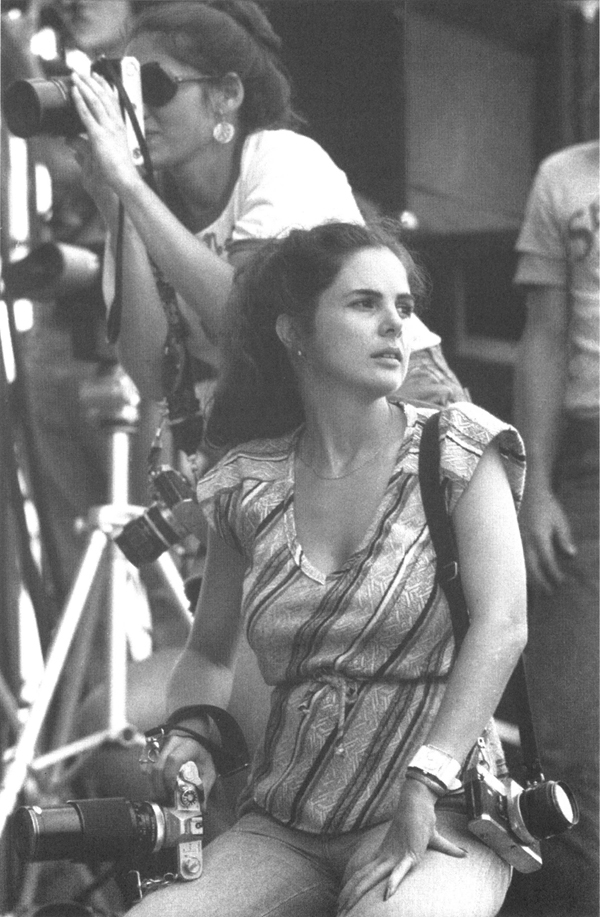

MELINDA WICKMAN

Class Act. In the 1970s Melinda Wickman was Austin’s most accomplished music photographer. Her photographs illustrated the first editions of this book but were later destroyed in a flood. From Austin, our friend moved to work on movie sets and settled happily, despite the loss of her priceless archive, as a school librarian and wife and mother in Vermont. 1974.

There was a lot of debate over the origins of all these beards, boots, hats, fiddles, and pedal steel guitars. One theory held that Austin’s music boom had tapped into a vein of maverick country and western that went back to Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys. Willie Nelson and Asleep at the Wheel supplied a great deal of credence to that interpretation. I pushed the other line that Armadillo World Headquarters had more in common with Bill Graham’s Fillmores than with the Grand Ole Opry. In Austin music I heard echoes and refrains of Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters and The Whole Earth Catalogue. Of course, I listened with prejudice. My boyhood was tuned in to Elvis Presley and Buddy Holly, not Hank Williams and Ernest Tubb.

My favorite concerts took place in Hill Country meadows that long ago vanished in Austin’s pricey suburbs. One rare evening transpired at a place called the Bull Creek Party Barn. What I remember best was the incredibly lovely changing light of the sky. The afternoon was warm; people were swimming nude in the clear-running creek. But then a norther blew through, and soon campfires were blazing and throwing sparks at the sky. The Armadillos were mixing the sound and videotaping the players on an outdoor stage. They included Bobby Bridger, Willis Alan Ramsey, Jerry Jeff Walker, and Willie Nelson. I don’t remember who was on stage, but it was just past dusk when someone grabbed the mike and blurted that Richard Nixon had fired his Watergate inquisitors in the Saturday Night Massacre. Tell me that was a stock country-western scene. A breathless “ooooh” rose from the crowd then fast changed into cries of outrage and strange glee. We howled for his head and danced all night. Lord, those years were fun.

Our book churned toward production. To meet advertising deadlines David needed a cover image; we all agreed it should be a picture of Willie. Melinda strapped her bags of camera gear across her shoulders and headed for a venue where Willie was playing. Her jaw dropped when he walked out of the wings with a clean shave and a Big Spring haircut, grinning at the audience’s reaction. Without the hair and beard, the most charismatic man in Texas looked like Elmer Fudd.

The locks and whiskers weren’t going to grow back out in time for our book cover. I nominated a shot of Jerry Jeff singing and grinning at a young woman who flung her arms and boogied at the foot of a stage. But the photo was slightly out of focus and would only get worse in the printing. Which was apt, once we thought about it—everything about Jerry Jeff’s life seemed to be slightly out of focus in those days. Murphey was in the process of deciding he would henceforth be Michael Martin Murphey; the portent of the makeover wasn’t quite like Cassius Clay becoming Muhammad Ali, but there was an element of that. “Cosmic Cowboy” and “Alleys of Austin” had been songs of definition. Murphey helped Austin become a stage and breeding ground of singer-songwriters, and the “supernatural country-rockin’ galoot” personified their ascendance and airs in the seventies, even as he got the hell out of Dodge. And Melinda had a performance picture of him beatific in a cowboy shirt, blond hair gleaming in yellow and green light.

But our cover boy hardly thought it was an honor. Murphey hated it. He didn’t think I had the credentials to write about him or any other musician, and he despised the ideological drift of the expression “redneck rock.” He didn’t want to have anything to do with rednecks. Everything about his life and art was meant to repudiate rednecks. Poor Joyce Lindsey was captured on the Heidelberg phone one day and got to listen to him shout. The Armadillos were videotaping everything that moved in those days. With a cheerful note, Eddie recently shared a transcript of a conversation that surfaced in the retrieval and restoration of those priceless tapes. Eddie was annoyed at Michael because the owners of the Texas Opry House were saying snide things about the Armadillos and vowing to put them out of his business, and now his old pal from the North Texas State folk music club was lending his name and star billing to a benefit that was trying to bail the Opry House out of a jam with the Internal Revenue Service. Eddie thought he had Michael’s commitment to play the Armadillo that night.

Murphey: I’ll tell you what I’ll do. Put on paper whatever you lose, and I’ll make—

Wilson: I can’t lose nothin’. I can’t—I ain’t got nothin’ to lose, man.

Murphey: Well, whatever you lose, like if you have to make a payroll or something by me doing this—when I come back, whenever I come back, I’ll make it up to you.

Wilson: Whenever you come back? He’s the ethereal kid.

Wilson: And you’re going to go back to Colorado with them goddamned mountains and blue skies—

Murphey: How many goddamned times have I played in your place, man, after so many people have come there and you—we may have misunderstandings, but there’s lots of people that won’t play there no more. And I—

Wilson: Hey!

Murphey: —still play there.

Wilson: You name them! You name them. And I’ll tell you what. There’s a real good chance if those people won’t play my—I mean you read the book. You’re talking out of the book that you don’t like. And it says a lot of people shun the Armadillo and some of the people are shunned by the Armadillo.

Murphey: No. I—

Wilson: But you name them people. You name the people that won’t play the Armadillo, and I’ll swear to God there’s a fat chance they’re going to play it pretty soon . . .

Murphey: . . . All I’m saying is you never had to—you know, you never had to worry about—

Wilson: Oh, Michael, I worry more about you playing there than anybody I can think of. Every time you’ve played there, I’ve had cause to worry. You worried. And a big part of the time, you’ve been right. You’ve said, ‘Something’s fucked up; I’m pissed’. And I’m—‘Oh, my God, he’s pissed again.’

Wilson: [turns to the subject of me] He comes in talking about how I run a beer joint? He don’t know nothin’ about running a beer joint. . . . The asshole that wrote that book is a groupie, and he quoted a junkie about how I’m trying to operate to keep alive. And it’s in hardback, so it’s history; there ain’t nothing we can do about it. There ain’t nothin’ we can do about it. . . . That book is hardback, so it’s history. You—

Murphey: There is one person sitting in this room that can do something about it.

Wilson: You go to the library in ten years. And if you’re in the eighth grade and you’re writing a paper on the Austin music scene and you pull that book out, no matter how many reviews I write, it’s history. I was educated in those libraries.

Murphey: I’ll bet you one thing, though. I’ll bet I’m the only one that can take that book off the market right now. And I’ve got a lawyer to prove it. [Wilson snorts; Murphey goes on.] Guess who doesn’t have written permission from me to use that picture on the front of the book?

Wilson: He doesn’t have written permission from me. And I’ll admit my picture’s kind of bad, but yours is good. Now, you can’t deny that. You got a good picture.

Murphey: Yes. But you’re not on the cover.

No suit was ever filed. When I saw Michael again, his son, whom I had known as a toddler with knee-high red boots and a ukulele, was a tall, handsome young man playing guitar and singing on television with his dad. Michael seemed happy in the life he had made in northern New Mexico as a minstrel of the last days of frontier cowboys and Indians. He came over to chat, and I was pleased to learn the hatchet between us was long buried. I’m told he would come to the Kerrville Folk Festival in boots and hat and duster—the Lonesome Dove look—and gloat to the old hippies, Armadillos, and lefties that he and Rod Kennedy were the only right-thinking Republicans on the grounds. Kennedy recently sold the festival, which under his watch and guidance became a Texas institution. Eddie long ago became a friend of my family and a frequent ally in our political agitations. But in 1974 I had completely alienated the performer who first drew me to the subject and the most important and enduring businessman and champion Austin music ever had. Among the people I was writing about, there was no consensus my book had gotten it right. And on that front things got worse before they got better.

A prominent Texas district attorney with a broad knowledge of Fort Worth had told me that, rightly or wrongly, police in that city used to associate Willie Nelson with drugs other than marijuana, and Willie was furious when he saw that in print. He made no secret of his love of cannabis but swore he’d fire anybody in his bunch whom he caught using hard drugs. But the scene was changing quickly, and the changing fashion in drugs was part of it. “Everything changed in 1974,” Marcia Ball told me flatly. “Eddie Wilson always maintained that Austin was predicated on beer and cheap pot. But 1974 was when we started seeing cocaine.”

Freda and the Firedogs ran its course like most bands, and its end was symbolic. A lottery had been instituted for the Vietnam draft, and the gifted west Texas guitar player, John Reed, drew one of the black beans. Without Reed, Marcia said, the band lost its center of gravity. Their last gig was at Willie’s Fourth of July Picnic at an auto race track near Bryan and College Station in 1974. “It was the first time I yodeled onstage,” she said. “I was debuting my ‘Cowboy Sweetheart’ routine, and I was so excited. At the start of the song I’m singing and yodeling when an airplane flies over, then these two guys parachute out of the plane with smoke bombs on their ankles. Every head in the crowd was turned. Nobody was paying any mind to me and my yodeling.”

That wasn’t the only smoke that picnickers came back discussing. The accomplished singer-songwriter Robert Earl Keen was then a diffident undergraduate at Texas A&M. He did have a flashy Ford Mustang and, he hoped, a hot date. Someone ran off with his girl, and as he brooded over that, smoke and flames erupted in a parking lot. Cars were destroyed by the fire. In fear of exploding gas tanks, people ran for their lives. Keen said he listened in disbelief to the announcement of a license plate number that belonged to him. His prized car was a total loss. (A Mustang in flames would later make a droll cover for one of his records.) “Everybody there felt so bad for me,” Keen told the story, “and somebody said, ‘Hey, would you like to meet Willie?’ They took me to his bus, and he came out for a minute. He said, ‘I’d really like to talk, but I’ve got to go jam with Leon Russell.’”

“I got in a lot of trouble over that festival,” Marcia Ball said. “I just saw a lot of things I didn’t like. It was chaos. We came home, and some neighbors were out doing yard work. I told them all about it. Well, one of them was a UPI reporter, and he went right to work and wrote a very unflattering description of Willie’s picnic, quoting me. I never saw the piece, but one day I flounced into Willie’s pool hall to put up a poster for a gig. The room got very quiet. Then Willie’s mama said, ‘That’s her. She’s the one.’”

About that time, “outlaw country” became the generic for Austin music. The metaphor was employed to convey the musicians’ rambunctious and far-roving styles and their rebellion against the industry, especially in Nashville. But some people took the outlaw routine to heart. David Allan Coe was a broad-shouldered ex-con and country singer of considerable talent, but he went around boasting of murdering a man in prison with a mop wringer. At an outdoor Outlaw Concert west of Austin in 1976 Coe wore a sleeveless denim jacket stitched with motorcycle gang colors and a swastika. His entourage of Bandido bikers had pistols bulging in their jeans. Coe’s latest song on jukeboxes was “Willie and Waylon and Me.”

Scarier than Coe was a biker from California who insinuated his way onto Willie’s bus and into his entourage. Unlike the other bikers, he wore his gun holstered. Everyone called him “the pistol whipper.” Texas Monthly editor Bill Broyles talked me into writing about the hokum. They titled the story “Who Killed Redneck Rock?” A graphics artist illustrated it with the backside of a country singer who had a pistol in the back pocket of jeans, a hunting knife lashed around one boot, and a cowboy belt hand-tooled to read “Bad Ass.”

Broyles was right to heap scorn on the mood of street fighter chic that was taking over, but the by-line didn’t have to be mine. For an eight-hundred-dollar payday it probably wasn’t the smartest career move I ever made. Willie let it be known in a trade journal interview that he was deeply offended, predicting that next I’d be writing about “the reincarnation of redneck rock.” One night in the Austin airport some shouting women—one of them Willie’s wife at the time—informed me that a number of large and angry men were eager to get their hands around my neck. Poor John Reed. Not only did the guitarist get drafted; he had a name that closely resembled mine. The pistol whipper knew what people called him. One night at the Rome Inn the lout (who has since passed from this life) banged Reed around a dressing room, thinking he was author of the article. First line of a country song: It was a severe case of mistaken identity.

For several reasons I decided it was time to go live in the country. Chastened by the beating he took publishing my book and a few others, David Lindsey bore down and became one of the country’s most thoughtful writers of crime novels—A Cold Mind, In the Lake of the Moon, Body of Truth, and many more. Melinda took photographs of Willie and many other musicians for a while and then caught on as a still photographer on movie sets. There she met the young director who became the father of her children. When that marriage ended she stayed in their house in a Vermont village on the Canadian border, and she became a school librarian. All of us were stunned and sickened when a flood destroyed almost all the negatives of the vibrant pictures she had taken of the Austin music scene.

Melinda had a good friend named Scott Newton. Scott was also a photographer of rare talent and flair. They were competitors; below the stages and in the wings they often worked side by side. But Scott was a colleague of such generosity that he manned the darkroom and delivered Melinda’s prints so that she would have a chance of making our deadline—and recording a phenomenon that was as intimate and important to him as it was to us. Scott went on to have a distinguished career, working primarily in the fields of music and politics. No single photographer can match the continuum of his vision of Austin music—images as fresh and vivid today as they were in 1974—and it is this edition’s great luck that Scott again shared his time and carried on with fondness and the spirit, if not the same style, of our friend.

AFTER A FEW SEASONS of rural sojourn I moved back to Austin, married, and joined in the rearing of a child. I bought a lot of music as vinyl albums turned into casettes and CDs and the term “record” became almost obsolete. But I didn’t write a line about music for twenty years. I didn’t think I ever would again. My wife Dorothy and I would read the club listings and talk about going out to see some favorite singer or band, but we almost never did. With dogs dozing near the speakers, we stayed home and listened to them. Someday I hoped to have a long talk with John Reed. I always figured I owed that guy a drink.

FROM THE NIGHT he first walked onstage at Armadillo World Headquarters, Willie Nelson was always the exception. Willie loved concept albums—a sequence of his songs and interpretations of others’ songs that formed a larger story. On the heels of his Shotgun Willie embrace of Austin, Phases and Stages had explored a love and marriage falling apart. In 1975 he decided he wanted to tell a story set during the long sunset of the Old West. Red Headed Stranger was recorded in a week in a Dallas advertising studio with a budget of under twenty thousand dollars. The singer said that one CBS executive, who had not been wholly thrilled when the label signed him, listened to the product and said: “When are you gonna finish it? It’s a pretty good demo tape, but . . .” The story was a twist on High Noon, and in time Red Headed Stranger was made into a movie adapted and directed by the emerging Austin filmmaker Bill Wittliff. Red Headed Stranger enlarged the perception of Willie as one of the outlaws, and he capitalized on the image with Waylon Jennings duets such as “Mamas Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys”—they seemed like bones tossed to the hillbilly crowd. But Willie was on a much more ambitious and inventive track.

He was an exceptional songwriter and guitarist, and as a singer he never stopped growing, never lost his curiosity over what he could make his voice do. And he was a devoted student of American song. The cut from Red Headed Stranger that endured and vaulted him higher up the ladder of commerce and acclaim was an interpretation of Fred Rose’s “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain.” Rose had started out as a pianist and pop songwriter in Chicago and eased into writing country tunes in the forties for Gene Autry. That was as close to six-shooters and lariats as Willie’s version came. It was all understatement, taking his time, and he finished with a triumph of haunting, gentle heartbreak. Three years later, he released an album that he and his band had recorded on a California ranch with the arrangement and imprimatur of the producer Booker T. Jones—famous for his jazzy blues group Booker T. and the MGs. A photograph for the album had Willie posed against a desert backdrop out West; he wore a blue neckerchief and a yellow-collared jacket and a black top hat with a brightly colored headband of Native American styling, the ends of his hair resting on his collarbones. The quintessential, self-amused redneck hippie. But his choice of material came from a completely different time in American music and culture—Duke Ellington and Irving Berlin, the Gershwin brothers and Hoagy Carmichael, “Georgia on My Mind” and “Moonlight in Vermont.” His fans, he assured nervous record executives, were so young now they would think these were new songs. The executives may have thought Willie was smoking too much weed when he dreamed up Stardust, but it was the same canny intuition Ray Charles had shown in 1962 when he made Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music. The voice and stylings freed the songs from pigeonholes of generation and genre—the audience response was part nostalgia, part discovery. In time Stardust went quadruple-platinum—whatever that means in the industry’s volume-speak. But he was a superstar now. And in many ways that put Austin in Willie’s rear view mirror. “On the road again, just can’t wait to get on the road again . . .”

No one ever celebrated the country musician’s lifestyle more. With the theme blaring from his second movie, Honeysuckle Rose, he was off down the road in his band bus of the same name. Somehow he kept a blur of balls in the air. He was gaining a reputation as a capable actor. Pauline Kael, the longtime critic for the New Yorker, thought he was riveting on the screen. His best performance may have come in just his third movie, 1981’s Thief, with James Caan and Tuesday Weld—he played a very convincing burglar. Willie bought the golf course of a failed subdivision west of Austin so that he and Darrell Royal, writer Bud Shrake, and other cronies wouldn’t have to fool with tee times. He played his songs on the roof of Jimmy Carter’s White House with Washington all alight before him. But it was never all blue skies for Willie. Marriages came and went. He took a nap one night outside a friend’s truck stop near his hometown of Abbott and was awakened by an officer who found his dope stash in the car. A debacle with the IRS left him so broke he could only start to dig his way out by playing retirees’ clubs in Branson, Missouri. His oldest son hanged himself. He told another friend in Austin, the writer Gary Cartwright, that nothing had ever laid him quite so low.

Willie was an extraordinarily complex man. He reminisced with Cartwright about a Phoenix brawl in which he slashed away with a two-by-four at a cuckolded husband who came after him with a wrench. His longtime stage manager loved to tell a yarn about a gunfight that erupted around the bus in a parking garage in Birmingham—with cops doing much of the shooting. Willie steps out of the bus clad only in cutoff jeans and tennis shoes, two pistols stuffed between denim and loins. “Is there a problem?” he says. The guns fall quiet, and soon the cops have him signing autographs. Well, maybe. Willie said that for him the music business was writing songs, making records, and doing the show at night—everything else was somebody else’s job. That need to insulate himself was always key to understanding Willie. Even his “family,” a band with the cohesion and legs of the Rolling Stones, knew that part of their job was to keep the world and its complications away from the man. Some members of the cast were more charming than others. Willie claimed that a demon temper dwelled within him. Yet he was one of the funniest men I’d ever met. A New Yorker writer recounted Willie’s quip when a flattering comment likened him to Abraham Lincoln: The president wakes up after a wild night and says to his friends, “I freed the what?” Country-pop radio tended to relegate him to the seniors tour; outside Texas he had trouble getting on the air. But he continued to churn out the records, sometimes half a dozen a year, and he never stopped pushing his range and interest. Along the way he turned into more than just a celebrity musician. In myth and talent and track record, the former Nashville songwriter and Armadillo headliner became country music’s equivalent of Frank Sinatra.

I didn’t see Willie again until 1990. After the Texas Opry House failed, he reopened it as the Austin Opry House under the management of Tim O’Connor. He played there one night at a benefit for the campaign of Ann Richards. She would ultimately be elected governor of Texas, but that night she was twenty-odd points down in the polls to a Republican oilman and cowboy, and nobody thought she had a chance. The evening was a closing of the circle. After it was over, Willie saw and recognized me, and he came over in his sprightly walk. I flinched and waited, having no idea how it would go. His grin lit up and he stood pumping my hand, saying it sure was good to see me again, and, you know, I believed him. In his presence I melted. I always had. I couldn’t help liking the man. He had known Lee Cochran, my trumpet-playing neighbor in a western swing band, and he had once made music in the MB Corral.

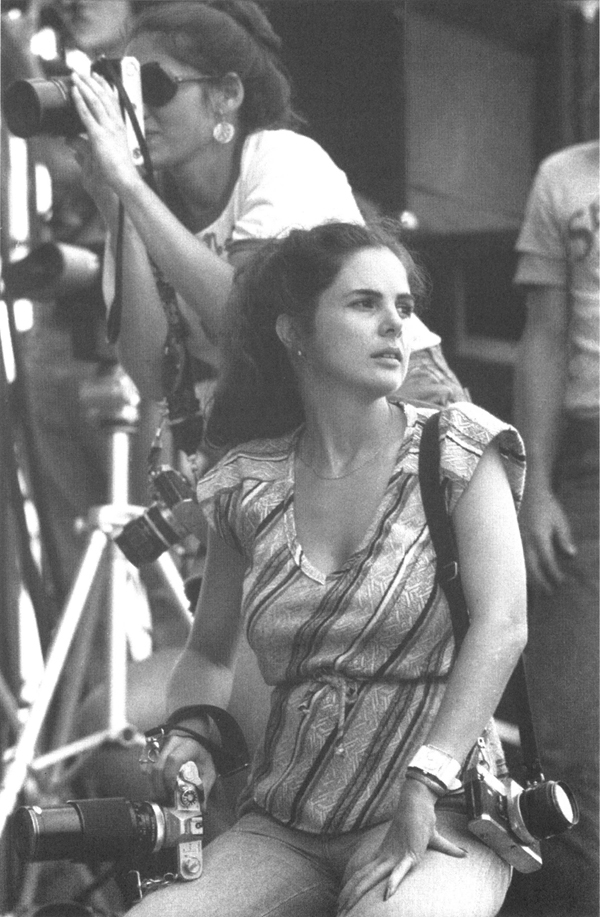

RAY CHARLES AND WILLIE NELSON

Star Dust. Not long after his commercial breakout as a national star, Willie Nelson had been irritated by a prior photo session. “Keep it brief,” his assistants cautioned about this shoot at his recording studio with legend Ray Charles. The second shot was all it took to tell them: “That’s it, we’re done.” 1985.

IN AUSTIN Willie was a hard act to follow. The odds against anyone making that kind of star breakout are long. Despite all the promotion and fanfare, B. W. Stevenson’s record sales failed to deliver. Bobby Bridger became as much a dramatist as a musician in pursuing his magnum opus about mountain men and Indians, and Willis Alan Ramsey’s “long-awaited second album” became a source of puzzlement in Austin, and then humor. Still, it had happened for Willie, and the prospects of the younger country-rockers seemed reasonably bright. Jerry Jeff Walker had a contract with a major label, MCA, and his 1975 release, Ridin’ High, was arguably his best. “Jaded Lover” articulated a comedown for a generation that had enjoyed sexual mores of easy come, easy go: “The only kind of man that you ever wanted/was the kind you knew you’d never hold very long/Sitting there crying like I’m the first one to go.” But the sing-along cut for Walker’s faithful was the closer, “Pissin’ in the Wind.” In his own life, Walker had taken a large gulp of self-preservation. His wife Susan became a shrewd manager of his business affairs, and they started a family. They named their son Django, in honor of the legendary guitarist Django Reinhardt. (The youth may have been more thrilled by the honor when he decided to follow his dad into music than when he was a sophomore at Austin High.) Steve Fromholz finally got a break and put his fine songs on a record. And Rusty Wier, who for so long seemed to be running in the pack, jumped out with a hit called “Don’t It Make You Wanna Dance.” He was tall and charismatic, he could roar like one of the old blues lions and still stay on key, and he always had the best-looking hat. He was packing in crowds like Waylon Jennings. The cosmic cowboys even had their own TV show.

Austin City Limits had begun in 1975 with a burst of university construction, not creative expression. A building surge engineered by University of Texas regents chairman Frank Erwin transformed the campus’s public television outlet—then called KLRN, later changed to KLRU—from a hole-in-a-wall into a full-blown station with multiple studios and pricey equipment. The program director, Bill Arhos, was a burly, mustachioed man of Greek ancestry and a onetime star pitcher for the Rice Owls. He took one look at the sudden wealth of technology and started searching for a program concept he could pitch to PBS. “I got the idea for Austin City Limits from reading your book,” he remarked to me in passing, years later.

“What?” I said, startled.

“Well, what was the most visible cultural product of Austin? Music. It was obvious. It would be like ignoring a rhinoceros in your bathtub.”

Arhos enlisted as his talent consultant Joe Gracey, the pioneering KOKE disk jockey who had been stricken with throat cancer. PBS executives liked the fundraising pilot, which starred Willie Nelson, enough to authorize thirteen shows for its 1976 season. The early tapings had none of the polish that later came to be associated with the show. Heads and shoulders rose up in front of cameras, which moved around in clunky view. At first, one of the biggest problems was drawing a crowd. “We were begging people to come in off the street,” Arhos said. “My favorite was a guy who’d been sniffing paint. You could see it on his mustache—silver. He had a terrific time.” When artists forgot a line or hit a bad note they kept on going—they were bar musicians. The Lost Gonzo Band launched one show with a song about dead armadillos; then Jerry Jeff came slouching onstage with his shirttail out. He looked up at one point and grinned at somebody dancing in a gorilla suit.

The program survived because it was genuine and different; the only rival country music show on the air was the cornball Hee Haw. Gracey lured Bob Wills’ band, the Texas Playboys, out of elderly retirement for a pairing with their western-swing descendants, Ray Benson and Asleep at the Wheel. But one of the classic shows could never be aired. You had to wonder what someone with as keen a commercial instinct as Kinky Friedman could have been thinking. He came on with blue sunshades and a matching chenille guitar strap, cigar smoke billowing. The first song was about Amelia Earhart’s plane crash and moved on to his lust for a former professor: “Although you’re thirty/I still think you’re purty/Let’s give it the old college try.” He went on, “This next particular booger is in the area of the Old Man, the Boy, and the Spook”—the Holy Trinity. Kinky and the Texas Jewboys put on a profane, wildly funny, clarinet-tooting, roaring good time, but nobody but the studio audience and a few video collectors ever got to see it. PBS programmers were aghast by the time they got to “Asshole from El Paso,” if any watched it that long. Kinky either sensed he was moving off in search of a new way of making a living or was dreadfully naive about what would fly. Arhos offered stations the satire as a “bonus,” but there were no takers.

While the cosmic cowboys were riding high in Austin, Terry Lickona had been a rock deejay at an FM station in Poughkeepsie, New York. When the management ordered a switch to a country-western format, they let him keep his job and play whatever he could stand to listen to. “Callers kept telling me I ought to go down to Austin, where there was actually a music scene close to what I was playing, so I did.” After making the move in 1974, Lickona was disappointed in his hopes of bowling over Austin radio and took a public-affairs job at the campus TV station; in 1979 he became Austin City Limits’ full-time producer. During Lickona’s first season, he brought in the gravel-voiced, throwback beatnik Tom Waits. With clouds of cigarette smoke, Waits lounged in red and blue light between two antique gasoline pumps with a spare tire slung over his arm, rambling on for ten minutes in Kerouac fashion about Burma Shave and alienated youth. It finally became apparent this was a prelude to his singing “Summertime.” “I still don’t know how that got on there,” Arhos grumbled for years.

Artists’ use of tobacco, highly visible in the early years, vanished when the university imposed a no-smoking policy. A more telling disappearance was the music scene that spawned the show. Texas country-rockin’ galoots turned out to be a regional phenomenon. Station by station, the progressive country FM radio format collapsed and died for lack of sponsors. The Armadillo was struggling through its last days, and suddenly the club rage in Austin was disco. A PBS executive flew down to see this hotbed of creativity, and Arhos drove her all over town in mortified search of one country band.

Austin’s live music revived quickly, but it came back first in the form of punk rock. In the late seventies a young writer named Jesse Sublett was playing bass in a garage band called The Skunks. With songs like “Push Me Around” and “Gimme Some,” they became a sensation at a university-area club called Raul’s. Margaret Moser, a critic for the alternative weekly the Austin Chronicle, wrote of their first gig in 1978: “That evening was a turning point in Austin’s musical history. Dozens of bands came in the Skunks’ wake. The sounds and scenes shifted from punk to New Wave to hardcore to cow punk but always The Skunks blasted away with unrestrained defiance.” Sublett hyped the band as “the rock-and-roll band who blasted Austin, Texas, out of the cosmic cowboy era and helped put Austin on the rock-and-roll map.” Sublett chased his music dream to major clubs in New York and Los Angeles before establishing a career writing screenplays and mystery novels. “I was really hostile to the cosmic cowboys,” he told me. “But hostility was a credential of being punk. Also,” he sighed, “I was drinking a lot then.”

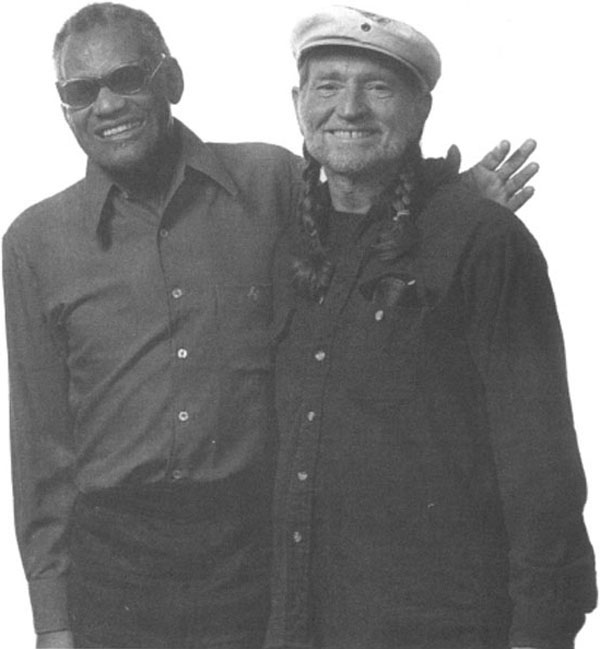

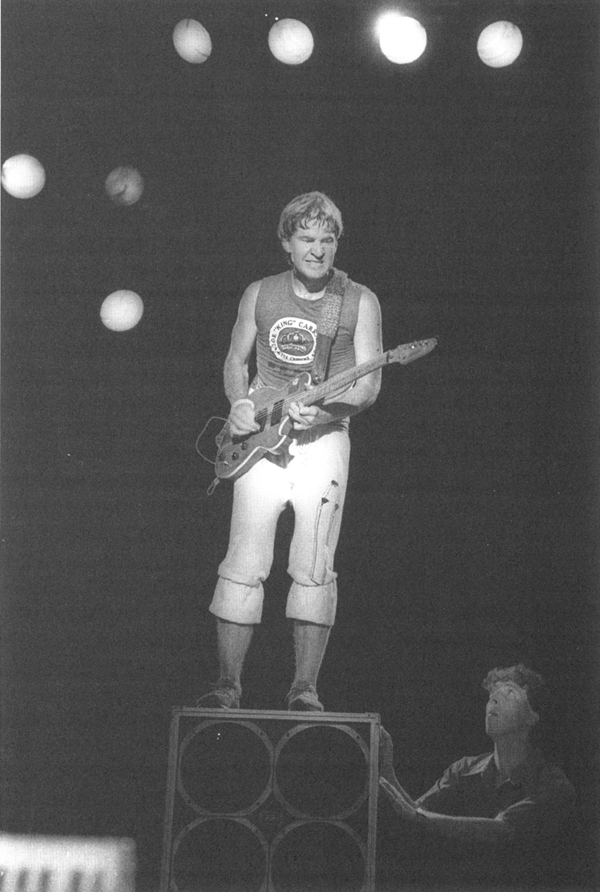

JOE “KING” CARRASCO

Poised. In this performance at Austin’s Auditorium Shores, a stagehand prepared for the recoil of Carrasco’s signature plunge into the crowd. 1984.

Youths with green spiked hair crowded into Texas clubs that tended to favor abandoned warehouses. The best-known in Austin was called Club Foot. What could the cosmic cowboy TV show do with this? The producers of Austin City Limits might have decided to follow Texas music wherever the changing styles and emphases took it, but there was little doubt that PBS executives would have suffered whiplash and ceased to renew the show. The nearest Austin City Limits came to the punk scene was the 1981 season finale, which paired Joe “King” Carrasco and the Sir Douglas Quintet. (Ever adaptive, Doug Sahm recorded part of a live album at Club Foot.)

Carrasco took his stage name in honor of Freddie Carrasco, a San Antonio drug dealer and psychopath of the seventies who met his end in a hail of bullets during a Texas prison siege. After finishing a gig, the musician would fling himself into the arms of his fans, who tossed him about and sometimes dropped him on his head. He restrained from that on Austin City Limits, and the San Antonio-roots pairing made artistic sense, but at least one station manager jerked the plug and wrote an angry letter because Carrasco wasn’t country. But for every offbeat act like Carrasco there were ten productions of Don Williams, Roy Clark, Johnny Rodriguez, Larry Gatlin. Lickona had to be a master of creative booking. He couldn’t cover the big acts’ travel to Austin, and he could only pay them union scale. He worked hard to convince them they were going to like this show, that they should swing by when their tours had them in the area. The show brought in musicians of national stature—Ray Charles, Jerry Lee Lewis, Emmylou Harris—even as complaints arose that the producers ought to rename it Nashville City Limits. They really had nowhere else to go.

One performer who seemed to sense it coming was Marcia Ball. “My husband and I moved out in the country,” she said, “and I got pregnant in 1977. I didn’t go out on the road for weeks at a time anymore; I was pretty much a weekend warrior. With Freda and the Firedogs, we were truly doing what came naturally. We were all hippies and had come up on soul and rock and roll, but everybody has a certain amount of country in their heads and ears. But I’ve always believed that people’s music interests are a lot broader than they’re given credit for. Even then we had this “Crazy” medley in which we’d do “Crazy Arms” by Ray Price, “Crazy” by Willie Nelson, and “I Go Crazy” by James Brown. I always followed the lead of musicians I worked with. Like finding a guy who played clarinet and baritone sax: the clarinet was right for the Louisiana stuff I’d grown up with, and the baritone sax was in the pocket for blues. Or a steel player who could play the accordion. Ray Benson listened to him and said, ‘You gotta pay him more.’

“You’d have to line me up with something to see that I was moving,” she reflected. “But about 1980, I just decided I was going in a new direction. The movie Urban Cowboy had just come out, and it was all the rage. Mechanical bull riding, all that. People would ask me, ‘Why in the world would you change when country is getting all the press?’ And I’d say, ‘Oh, but listen, there’s something bubbling under the surface in Austin, and when it comes up it’s going to be wonderful. Blues is going to be the Next Big Thing.’”