Olympic archer Ed Eliason tells of a Buddhist monk who advised him, “When you wash dishes, wash dishes.”1 At first the monk’s Zen-like thought seemed obvious to me, of no particular value, but upon reflection it began to make more sense. Eventually, I translated it into a phrase that had significance for me: “When in charge, be in charge,” a frequent admonition from General Max Thurman, commander of the 1989 Panama invasion. Being in charge of any organization puts a burden on the shoulders of the leader. Being in charge means that you must create the future.

My mind, like that of most leaders, was usually focused on today’s issues, oscillating between today and tomorrow but always returning to the pressure of today. It was hard to focus on the future. To handle that tension, I had to find ways to act in today’s world while at the same time focusing on the future. I understood Creighton Abrains’ and William DePuy’s lessons about values and the role of doctrine; Shy Meyer had taught the Army the importance of quality people and had highlighted to the American people t taught me the importance of keeping he danger of hollow units; and Carl Vuono and others hadthe Army training, especially during times of turbulence and uncertainty.* Those were touchstones I could not walk away from. But I had to translate them into the future even as I was forming new ones. Our long-range planning processes had not been designed for the kind of world we were facing, with its uncertainty, ambiguity, and rapid change. Our planning processes had been designed for a stable planning environment and for incremental changes—for marginal resource adjustments and evolutionary technology.

The Army’s long-range planning system was dominated by the programmatics of the Future Years Defense Plan (FYDP), a budget estimate that described in fiscal terms how the Department of the Army would generate and sustain ready forces for the next six years. The stability of the Cold War had enabled us to create a planning and budgeting environment in which we had estimated the Soviet threat, modeled a hypothetical war with the Soviets, and made investment decisions at the margin based on that analysis. This tedious process, rooted in the Robert McNamara years, had yielded increasingly precise point estimates of the future. By 1989, investment decisions were being driven by a single war plan to defeat a hypothetical global Soviet attack. But by 1990, that methodology was moving us toward a future that no longer existed. Yet the machinery of the planning and budget process continued to grind on, attempting to accommodate change in an unending process of marginal adjustments, bureaucratic decisions, and ever-shorter planning cycles. The process itself did not really change much, even though dollars dried up and missions expanded and changed.

It was clear that, inside the Army, we needed a more robust way to think about an unclear, ever-changing future. On the one hand, we had to accept the limitations of the FYDP and its process because that was our planning reality—that was where the money came from. On the other hand, we had to transform ourselves into a new force that could not be reflected very well in the formal planning process, because the process demanded consensus and precision six or more years into the future—both of which were now impossible. We had to get out in front intellectually, learn about the future, and create it. Only then could we reach back and connect to the programming process in a coherent way What’s more, we had to do so in a way that would be as transparent as possible to our soldiers so that we would add as little turmoil and uncertainty to their lives as possible. It was very difficult to think about all that.

Our approach was to leverage the learning culture others had created to train the Army and thereby create a learning-based planning process. We postulated that the nation needed a versatile force that, although smaller, would be effective in a broad range of missions. Information would be the new source of power, not only in combat but in all of our operations, with a shared situational awareness creating an environment in which our units could operate much faster and much more effectively than any adversary. We called this future Army Force XXI. The essence of Force XXI is not managing the complexity of the Industrial Age battlefield more efficiently but raising the conduct of all kinds of military operations to a new level. Fleshing out the concept of Force XXI will be the kind of shift not seen since agrarian warfare began to yield to Industrial Age warfare in the nineteenth century. Setting out to create Force XXI was a way of breaking the tyranny of the Cold War planning processes and deliberately creating the future.

By disassociating Force XXI from existing processes, it was possible to begin the journey. But we still faced the challenge of creating the future while running the organization in the present. In other words, we could not ignore the force development and programming systems just because they had been perfected for a world that no longer existed. But our belief was that by a process of experimentation and discovery learning, it would be possible to feed the future back into the more formal planning processes. It remains to be seen how effective this will be. In some respects it is like joining two engines to a single transmission while both engines are running. But we have seen some early success in the revamping of the Army’s modernization strategy to emphasize a range of capabilities that extend horizontally across the force, as opposed to the traditional vertical approach along functional lines.

Force XXI was our way of taking the initiative. To create purposeful forward momentum, you as a leader must take the initiative. You cannot be passive. When your people look into your eyes, they are asking whether you have what it takes to get them through today’s crisis and whether you will be there for them when it is over. To be successful, you must lead to win in today’s context and have a powerful drive to succeed in the long run. If you are not attacking, you are defending; while there can sometimes be good reasons to defend, in the end you will win only by seizing the initiative and attacking.

—GRS

We are at the end of an era. There may be some seminal event that historians will point to as the turn of the century. Perhaps it will be the fall of the Berlin Wall; perhaps the development of ENIAC, the world’s first electronic computer; perhaps the commercialization of the microprocessor; perhaps…whatever; finding the most appropriate tombstone for that which is passing is unimportant. What is important is to realize that we are in what the Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Daniel Boorstin called a “fertile verge…a place of encounter between something and something else.”2 We stand between a bureaucratic industrial society and an information society. The skills we have used all our lives are falling short of helping us face the new world; it is a time of great opportunity but also of ambiguity and uncertainty. In times like this, management is not enough. Ours is a time for leadership.

There is a useful and important distinction between leadership and management. Management has to do with an organization’s processes—performing them correctly and efficiently; leadership has to do with an organization’s purposes.

Today, management science enables executives to deal with complexity. Think about the traditional management disciplines: human resources, information systems, operations, finance, marketing, communications, organizational behavior, accounting, and the like. Each is very focused. Each is compartmented. Management has at its heart the notion that, as the organizational design consultant and author Margaret Wheatley comments, “we really believed that we could study the parts, no matter how many of them there were, to arrive at knowledge of the whole.”3 Wheatley and other scholars are beginning to create an understanding of the role of leadership and learning,as distinct from management and controlling. We are coming to understand that leadership and learning are the tools we now need to develop high-performing organizations.4 The wisdom of these new approaches to organizational theory can be seen in the irony of the examples we used to illustrate the leadership traps. All six organizations were being managed very well—even McClellan was performing up to the expectations of his profession—but none was well led.

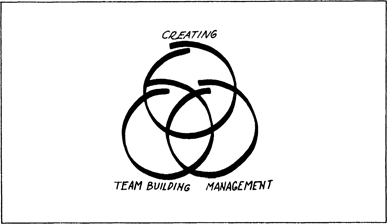

Leadership goes beyond creating the future and managing complexity. The leader must also build teams. A team is a permanent or ad hoc grouping of people to accomplish a task, and our organizations are teams of teams. Through teams, a leader influences and directs the course of the organization. From this perspective, leading is acting on an interpersonal level with small groups or individuals. It is communicating and aligning to influence behavior and performance. It is how we put creating the future and managing the present in context to move the organization, as a coherent body, from one state to the next.

Thus, “leading” has three dimensions, and we use the term “strategic leadership” to embrace this gestalt: managing, creating the future, and team building. Strategic leadership is directing and controlling rational and deliberate action that applies to an organization in its most fundamental sense: purpose, culture, strategy, core competencies, and critical processes. Strategic leadership includes not only operating successfully today but also guiding deep and abiding change—transformation—into the essence of an organization. If we picture the leadership dimensions as a Venn diagram (see Figure 3-1), it becomes clear that effective leadership depends on being able to operate with all three sets of skills. In terms of the diagram, strategic leadership is operating at the center.

Figure 3-1—Strategic Leadership

This model does not denigrate managerial skills, nor does it overly exalt the “soft stuff” of team building and other interpersonal aspects of leadership. Rather, it shows that all three kinds of skills are necessary for success: good management, working effectively with people, and creating the future.

One paradox of this new age is that information, by itself, does not represent knowledge, and therefore merely having more information is not in itself an advantage. It is difficult for leaders to internalize and act on the constant stream of information they are exposed to every day. In fact, trying to react to constant bombardment by “information” may be dysfunctional. In the seventeenth century, it took the better part of two years to turn around a message concerning European interests in India or the Far East. European managers on the scene were “empowered” far beyond our late-twentieth-century imaginings! Or think about World War II, when Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill had time to meet in the middle of the North Atlantic, both blacked out from being able to influence day-to-day operations, to reflect on the war at its strategic level and negotiate how it would be carried out. How many leaders today are able to step back and reflect strategically on what they are trying to accomplish? Yet that is precisely what leaders must do.

One of our favorite illustrations of leadership in action comes from a battle in Vietnam.5 By 1965, the North Vietnamese had moved large regular army units into South Vietnam to reinforce the Viet Cong guerrillas. In response, the United States deployed conventional units. In the first major clash of the two armies, Lieutenant Colonel Hal Moore led the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, into the Ia Drang Valley of the central highlands, into a clearing called “LZ X-Ray.” We now know that the North Vietnamese were seeking a major engagement to learn how the Americans would fight. Moore’s assault went into an area that had long been a Communist stronghold, and he and his men were quickly surrounded and fighting for their lives, outnumbered by four or five to one or more. The tough, bloody fighting went on for four days. When it was over, half the troopers from Moore’s understrength battalion were dead, as were hundreds of North Vietnamese. Moore’s command had distinguished itself against an enemy that was far superior in numbers and that had held the initiative throughout much of the battle. Ultimately, both sides would claim victory, but the tenacity of the 7th Cavalry and its indomitable spirit are a monument to effective leadership.

During the fight, Moore established his command post in the center of the primary landing zone, partially protected by a large termite hill. With his radio operators, forward observers, and others he worked the artillery, air support, and resupply while he led the battalion in the fight. From time to time he was observed to withdraw, appearing to those around him to be shutting down and blocking them out for brief periods of time. When the battle was over, Moore and his men were debriefed extensively to learn as much as possible about the North Vietnamese regular forces and how they had fought. When asked about his periods of seeming withdrawal, Moore said that he had been reflecting, asking himself three questions: “What is happening? What is not happening? How can I influence the action?”

What is happening.

What is not happening.

What can I do to influence the action.

Moore’s behavior captured the essence of strategic leadership. Moore was scanning his environment, thinking about his situation, then determining his best course. The future was winning the battle, not simply parrying each thrust. The genius in Moore’s approach lies in his second question. By reflecting on what was not happening, he was able to open his mind to broader opportunities, to see the full range of his options. He was better able to anticipate what might or might not happen next and to plan his moves to best advantage. When asking “How can I influence the action?” he could thus envision a far greater range of responses than if he had simply been thinking in terms of action and counteraction.

Few are presented with the challenge of leading soldiers in battle, but our leadership reflexes and intuitions must be similar. At Antietam, McClellan got the management right. At LZ X-Ray, Moore got the leadership right.

It is in Moore’s second question that opportunity lurks. Think of Eli Whitney: he “invented” interchangeable machine parts because of the shortage of gunsmiths in late-eighteenth-century America.6 Whitney saw opportunity by asking himself “What is not happening?” and answering “The traditional system is not meeting the demands of the market.” Henry Ford was not the first to make an automobile, nor was his the best. But he asked himself “What is not happening?” and concluded that the craft-based automobile manufacturers had assumed away the mass market. Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs asked themselves “What is not happening?” and concluded that IBM and the others had failed to grasp the power of computers in the hands of real people. Their Apple changed the lives of all of us.

The dynamic that makes all of this so vital is the speed of change. Things are happening so fast that a move in the wrong direction can quickly become overwhelming; for most of us the downside risk associated with our decisions is greater than ever before. Shortly after we had published an article about the future of the U.S. Army, a colleague wrote us, “You make it sound as if the Army is rushing headlong into the twenty-first century.” In his view, we were recklessly threatening proven ways of doing business, processes carefully built up over a generation or more. We wrote back, “The twenty-first century is rushing headlong into the Army.” From that inside-out perspective came this insight: The defining characteristic of the Information Age is not speed, it is the compression of time. If we think in terms of speed, we are back on the treadmill. But realizing we have less time suggests new limits to old ways; and we can open up a broader perspective and range of action, one more ominous in its implications but more challenging in its opportunities.

The leader seemingly no longer has time to digest the nuances of rapid and widespread change. It would be unfair and supremely arrogant to suggest that leading today is any more difficult than a generation ago or a hundred years ago, but it does seem fair to argue that change (whatever we take that to mean) is taking place much faster than ever before. Dee Hock, the creative genius who “invented” Visa International, coined the term “change float” to describe this phenomenon. He noted, “You may not recall the days when a check might take a couple of weeks to find its way through the banking system. It was called ‘float.’ Today, we are all aware of the speed and volatility with which money moves through the economy and the profound effect it has on commerce. However, we ignore vastly more important reductions in float, such as the disappearance of information float.” Events that once took months or years to become known and accepted can now be known virtually instantaneously. Hock concluded, “This endless compression…can be described as the disappearance of…the time between what was and what is to be, between past and future.”7

We can see the compression of time in the great campaigns of military history. The campaigns that Napoleon took seasons or years to accomplish could be accomplished in months by the dawn of the Industrial Age a hundred and fifty years ago and in weeks or even days today. The trend is equally unmistakable in the world of commerce. In the automobile industry, we see a proliferation of models and faster and faster cycle times. In telecommunications, we see unrestrained competition as more and more products and services are introduced daily. In retailing, we see traditional annual and semiannual product cycles reduced to monthly or even weekly just-in-time cycles. We see it in software development, in health care—in fact, in virtually every sector of economic activity. The game has quickened so that players have less and less time to play each hand. We live in a world in which the useful life of assets is unpredictable, workforce skills require continual renewal, and markets can disappear overnight, a world in which versatility and flexibility are far more valuable than specialization.

With less time to act, what you do to create the future becomes vitally important. Reflection is critical, but it must be connected to deliberate, structured action in an iterative, constantly adjusted leadership process.

The way a tank commander uses his tank follows a simple four-step model—observe, orient, decide, act—nicknamed the “OODA Loop.”8 First, the tank commander observes his environment, using all his on-board sensors, his human faculties, and whatever information is being broadcast into his tank. Upon observing a threat he orients on it, intensifying his data collection and information processing. Trading time for information, he gathers information about what the rest of his unit is doing, what supporting actions are under way, and the extent of the enemy resistance. Quickly, he decides what to do, and then he completes the cycle by acting. Today, all that happens very fast, at ranges of up to two miles, day or night. Feedback is immediate, and the cycle begins anew.

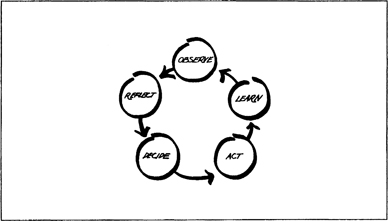

The challenge for the executive is much the same as it is for the tank commander. Integrating learning and feedback, more formally, he follows a five-step model we call the “Leadership Action Cycle”9 (see Figure 3-2).

Figure 3-2—The Leadership Action Cycle

Observe. The Leadership Action Cycle begins with observation. In this phase the leader is asking “What is happening?” and “What is not happening?” This is not only a process of looking outside the organization; it is also a process of looking inside and assessing strengths and weaknesses, basic competencies, cultural tendencies, and needs. It must include all of the organization’s constituencies, including customers, shareholders, employees, competitors, analysts, regulators, and whoever else has an influence on the ability of the organization to function.

Reflect. Reflection is the thinking phase: “What can I do to influence the action?” The leader interprets the information gathered by observation, deducing both threats and opportunities and formulating courses of action, options, and alternatives. In this phase, the leader establishes objectives. An important dimension of the thinking phase is determining what in the environment is subject to change and what must be accepted as a given. It is a process of segregating uncertainties from relative certainties and of identifying and testing assumptions. It is also a process of assessing and mitigating risk.

Decide. Next, the leader determines how best to go forward to realize the objective. This involves identifying tasks, including specific roles for the key participants, and setting constraints, limits, and measurable standards for success.

Act. The organization then begins to execute the leader’s decisions, often beginning with specific pilot projects so that learning can begin immediately. The leader must be personally involved, especially early in the change process. The leader’s sponsorship and involvement demonstrate the importance of change and reinforce participation by other leaders.

Learn. This most important step in the Leadership Action Cycle closes the loop by relating the outcomes of decision and action to the environment and to future action. In the learning phase, the leader and the organization modify their behavior to become more effective. They adjust decisions and refocus objectives as necessary, asking “If we had known then what we know now, what would we have done differently?”

Not only is more information available than ever before, but the compression of time means the leader has less time in which to digest and apply it. The leader can use assistants to help in this process—to dialogue about the situation, the alternatives, the risks, and the difficulties. Having an effective leadership team can greatly enhance the leader’s ability in each phase of the cycle, but a team may also tend to constrain the leader along conventional paths and make it more difficult to think “out of the box.” In the end it all comes back to the leader: “When you wash dishes, wash dishes.”

When Army forces went into Somalia in December 1992, their commanders quickly began to refine their estimates and plans using the Leadership Action Cycle. Their initial objectives were to work with international relief agencies to stem the starvation and dying. These goals were fairly quickly met, but longer-term solutions were initially elusive. As the commanders took stock of the situation, what they observed was that the food crisis had been created by the destruction of the national infrastructure, which in turn had forced people out of the countryside and into small towns and villages that could not support them. Thus, longer-term resolution of the crisis required the reestablishment of sufficient infrastructure to sustain the rural economy in the interior of the country. The key to that was the badly deteriorated road network.

The decision to act came quickly. The Army deployed engineer units to reopen the most critical road links. The project, nicknamed “Somali Road,” reopened more than 1,000 miles of road, opening the interior to relief agencies and truck convoys of food and matériel. Opening the roads prompted refugees to return to their homes from neighboring Kenya as well as from temporary camps in the interior.

The fighting that broke out in the fall of 1993, specifically the events of October 3 and 4, when Army forces engaged in bitter fighting in and around Mogadishu, makes it difficult even now to fully assess what we learned from our experience in Somalia. But the lessons of Somali Road were clear. An important step in this kind of disaster relief is fostering the reestablishment of the sinews of civil society, in this case the most basic elements of the economic infrastructure. The Army was later able to apply this lesson in Rwanda, where fostering conditions for the international relief agencies to reestablish themselves led to success, and in Haiti, where fostering conditions that enabled others to begin to restore the basic economy led to success.

RULE ONE; CHANGE IS HARD WORK

Leading change means doing two jobs at once—getting the organization through today and getting the organization into tomorrow. Most people will be slow to understand the need for change, preferring the future to look like today, thus displacing their lives and sense of reality as little as possible, Transformational leadership requires a personal and very hands-on approach, taking and directing action, building the confidence necessary for people to let go of today’s paradigm and move into the future.

Transforming an organization is hard work because the leader and his or her leadership team must do it. Change will not spring full blown from the work of a committee or a consultant. Not everybody will agree that you are doing the right thing. You will have to spend a lot of time communicating, clarifying, generating enthusiasm, and listening (including listening to negative feedback, resistance, and genuine disagreement). You will have to spend a lot of time away from your desk and get out where the critical processes of the organization are happening. You will have to personally work the organization’s external constituencies, including media that may not fully understand or appreciate what you are doing. You will have to think a lot about the future and make others do the same.

Leading change is hard work because it requires action. Your calendar and diary are the most telling evidence of your commitment. Are you spending your time with the traditional or the innovative parts of your organization? Are you fostering experimentation and learning? Have you delegated control within a wide range of behavior that people understand? Are you promoting the risk takers or those who represent business as usual? Are you pictured as reinforcing the status quo or championing change in in-house magazines, newspapers, and videos? Is your investment budget oriented to the past or the future? Does the organization filter what it tells you? In short, are you part of the “new” or the “old”? Words are important. What you say is important. But people look to your actions to validate your words; their behavior will reflect yours.

It is easy to say that leaders must reflect; it is also hard to do. There seem to be two ingredients: time and context. Both are difficult to find, although time may be the easier of the two. I took time to reflect in the study of history, more often than not in the context of our Civil War Battlefield Parks.

On one such occasion, the Saturday after Thanksgiving in 1994, I went to Chancellorsville, the site of an interesting battle best remembered for the tragic fratricide resulting in the death of “Stonewall” Jackson but more interesting to me as a contrast in the timid generalship of Union General Joseph Hooker and the risk-taking style of Lee and Jackson in their last battle together. In November 1994, we were facing one of our seemingly endless budget battles, we had troops in Haiti and the Persian Gulf, things were a bit uneasy in Korea, and Bosnia was threatening. It was not an easy time. In my notes from that day, subsequently transcribed into one of my periodic letters to the Army’s general officers, I wrote this: “As is often the case for me when I go on a staff ride, my mind moves from then—1863—to now, and I find myself thinking more clearly about a contemporary challenge…. We are now not unlike commanders on a battlefield—a bit overextended in our lines. It is now time to consolidate our lines while at the same time maintaining momentum, movement, initiative.”10 My notes go on to describe how, on that crisp fall afternoon, I saw our situation in 1994, as well as my intent, my assumptions, my fears. Taking time to reflect that day helped me clarify our strategic situation.

I also read a lot of biography. The ghosts speak to me. I told this anecdote to a group at West Point one evening:

“Here’s what one brigade commander, relating his first contact, said to me about that learning experience. ‘As we approached the brow of the hill from which it was expected we could see the enemy’s camp and possibly find his men ready formed to meet us, my heart kept getting higher and higher until it felt to me as though it was in my throat. I would have given anything to be back in Illinois, but I had not the moral courage to halt and consider what to do; I kept right on…. The place where the enemy had been encamped a few days before was still there…but the troops were gone. My heart resumed its place. It occurred to me that the enemy had been as much afraid of me as I had been of him…. From that event to the close of the war, I never experienced trepidation upon confronting an enemy…. I never forgot that he has as much reason to fear my forces as I had his. The lesson was valuable.’

“That brigade commander wasn’t out at the National Training Center. He wasn’t in Panama or Germany. He was Ulysses S. Grant, then colonel of the 21st Illinois Regiment of volunteers. He spoke to me, through his memoirs. Telling me to persevere.”11

History does not repeat itself. Going to battlefields and reading biography does not prepare one to solve tomorrow’s problems. Human nature and the human condition, though, do replicate themselves. Standing on battlefields asking “Why?” gave me insights into how other leaders have handled difficult and ambiguous challenges. Understanding Grant’s fears gave me counsel of my own. History gave me context.

Your context will be different. Some people tell me the most valuable part of their day is getting outdoors in the early morning, taking time to be alone with their thoughts, perhaps running or walking, stretching themselves physically. Some find their context during sojourns to new places. Some find it in a sport or hobby that forces their mind to switch gears and lock itself into a different world. What worked for me will not necessarily work for you and vice versa.

But you can make the time. And you can find your best context. You just have to do it.

As you reflect, you must ask the same three questions that Hal Moore asked himself in the Ia Drang Valley: “What is happening? What is not happening? What can I do to influence the action?” When all is said and done, being a leader is about standing up, making judgments, accepting responsibility, and taking action. Twenty years from now, people won’t ask how you did last quarter; they will ask whether or not you created a future.

—GRS

*“General Creighton W. Abrams, Jr., Army Chief of Staff from October 1972 to September 1974; General William E. DePuy, Commanding General, U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command, from July 1973 to June 1977; General Edward C. Meyer, Army Chief of Staff from June 1979 to June 1983; General Carl E. Vuono, Army Chief of Staff from June 1987 to June 1991.