On November 9, 1989, I was a keynote speaker at a conference sponsored by the Fletcher School of Tufts University. As I went onstage to make my talk, I was handed a note telling me that the Berlin Wall had just come down, news that I shared with the audience. During the question-and-answer period, the first question was about the unfolding events in Europe: “General, what does it mean?” I was tempted to speculate, but what was happening was too profound to be addressed in a quick answer from the podium. My answer was simply “I don’t know what I don’t know.”

No one had predicted that the Berlin Wall would come down. No one predicted that the Warsaw Pact and the Soviet Union would implode. No one predicted that we would go to war in the Persian Gulf, use forces from Europe, fight with Syria as an ally, and win a decisive victory. As we watched the victory parades after Desert Storm, no one predicted that George Bush would be defeated for a second term. Yet in the middle of what we thought was our downsizing plan, we made a transition to a Democratic administration that made additional, deep cuts in defense resources. No one predicted that we would deploy soldiers to Africa, to the Balkans, or to Haiti, that the U.S. 3d Infantry Division would train in Russia, or that Russian infantry companies would visit Fort Polk, Louisiana, and Fort Riley, Kansas. Yet all those things and more have come to pass.

Life is a journey with many unexpected twists and turns. The challenge for the Army was not to make better guesses about the future—which is impossible—but to build more flexibility and versatility into our planning and into the force so that when the time came we could tailor a response and get it about right.

We had a pretty good sense that the precision of Cold War-era strategic planning, programming, and budgeting was no longer relevant. Untold thousands of hours had gone into the development of the assumptions and databases in our Cold War models. The models and scenarios had been debated over the years, and while in hindsight they appear somewhat suspect, they had at least provided a common language and context for the development of the nation’s military forces. Suddenly those models no longer had any relevance, and there were few analytic tools at hand with which to replace them. We were planning, programming, and preparing future budgets under uncertainty, something with which the bureaucratic structure of the Defense Department has yet to come to grips.

Opting out of the formal planning processes of the department was not an option. So we attempted to keep things in context by directing our journey as if it were multiple campaigns—both sequential and simultaneous. Like Grant leading five armies, we were directing several campaigns; preparing for new missions, incorporating new technology, getting smaller, coming home from Europe, and writing new doctrine were only the major ones. On top of those came the missions we were actually performing around the world, each taking us another step further from the Cold War, each leaving its mark on the new Army.

Like me, most people want to “finish” things; but in an organization such as the Army, at a time like this, there is no “finish.” My tenure as chief coincided with the fiftieth anniversary of the United States’ entry into World War II. I thought about that a lot. World War II ended in V-E Day and V-J Day—clear marks of a successful conclusion. For today’s Army, and for most of our organizations, there are no such clear-cut finish lines, no perfect, enduring solutions. The campaigns I was leading could not be managed as projects with a beginning and end.

The demands of our world are constantly changing, and structuring things too rigidly can leave you ineffective at the next bend in the road. Part of us wants to believe that we can somehow get our organizations perfectly right so that, like the Great Wall of China, they will endure for centuries. As leaders, we must avoid the temptation to attempt to build such walls.

To be able to handle this journey, leaders must condition themselves and their people to be surprised, to handle the unexpected. We must build into our organizations the expectation that they will be surprised. I am convinced that no matter what path of life you walk, there will be surprises. Competitive advantage will come not from more precise planning but from planning that anticipates surprise in an active way. Good organizations become adept at what infantrymen call “developing the situation.”

When Ulysses S. Grant left Culpeper Court House in the spring of 1864, he did not know, in a specific sense, where he was going—but he knew what he wanted to accomplish. Grant’s road led through the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor, Petersburg, Five Forks, and only then to Appomattox. In November 1944, when Eisenhower held a council of war at Maastricht and approved the final plans for the invasion of Germany, he did not know that the German counteroffensive, the Battle of the Bulge, would erupt only weeks later. Omar Bradley and George Patton did not know that they would have to move north to go east. Eisenhower’s strategic concept was not a precise blueprint, planning chart, or timeline; but his campaign plan, in the hands of competent commanders and courageous soldiers, accommodated the Battle of the Bulge and provided the framework for moving on, leading to victory only six months later.

There is no substitute for insight or genius, but, when all is said and done, most of us do not see into the fog much better than our competitors. The competitive advantage we need is neither clairvoyance nor precision in planning. The competitive advantage we can build into our organizations is people who react faster than their competitors do.

The United States Army had no units specifically designed to go to Haiti or Bosnia. There are no books at the Staff College that tell precisely how to create such units. Instead, the Army was able to put the pieces together—not like Henry Ford but like an artisan, individually crafting each piece—and do it faster and better than anyone else.

It is comforting to think of this metaphorical journey as downhill stretches on sunny summer days, but my experience suggests otherwise. There will be potholes and uphill stretches; there will be ambushes, flooded rivers, and winter storms. There will be resource challenges and tough trade-offs. Leaders must prepare their people to appreciate the uncertainties and random nature of life and the necessity of anticipating the unexpected, always keeping the organization positioned so that it can respond. Successful organizations accept uncertainty and are not surprised to be surprised. Winning organizations are poised to find opportunity and to act faster than anyone else.

Expect to be surprised.

—GRS

In his biography of Lincoln, Pulitzer Prize-winning author David Donald tells of an exchange between Lincoln and Congressman James G. Blaine. Asked his plans about the postwar South, Lincoln responded with a story: “The pilots on our Western rivers steer from point to point as they call it—setting the course of the boat no farther than they can see; and that is all I propose to myself in this great problem.”1 The pilots knew where they wanted to go, be it Corinth, Cairo, or New Orleans. In our terms, they had a vision. But they worked to achieve it a piece at a time. They did not give orders and go to bed saying “Wake me up when you get us there”; they stood in the pilothouse and worked from point to point. In the ever-changing vastness of the Mississippi, every trip was a unique journey.

Thus, for an enduring organization there is no finite end state, only a journey—always becoming, never being. An institutional vision is not an end state, like reaching New Orleans. Rather, it is our guide as we go from point to point, dealing with the world’s uncertainty and ambiguity.

A leader must accept these realities and grow the organization to survive and prosper in an ambiguous, uncertain world that makes precise planning a business school exercise. With a strategic vision out in front, pulling the organization forward, the leader can focus on the journey one segment at a time. The journey will have unexpected twists and turns; actions will have unintended consequences; there will be “lucky” and “unlucky” events. But it is possible to direct a journey in such a way as to accommodate the unexpected.

RULE SIX: EXPECT TO BE SURPRISED

The paradox in creating the future is that you cannot predict the future. Success will come from being able to accommodate the unexpected, exploiting opportunity and working through setbacks, A leader must build flexibility and resilience into the organization, conditioning it not to be surprised to be surprised so that, when the unexpected occurs, response is prompt, action is deliberate, and the organization stays on course. The organization that is successful is the one that can best deal with surprise.

Use shared values as the foundation for action.

Create a vision that provides a sense of direction and purpose.

Build a strategy that is grounded in your basic competencies and processes to focus and direct your actions.

Communicate constantly; make change part of the culture.

Structure for success; create options to provide strategic flexibility.

Integrate and synchronize actions and events to achieve decisive results.

Expect the journey to take unexpected twists and turns; translate them into effective action.

Strategic plans must be inherently flexible, organized as a campaign—a series of related activities, events, or operations aimed at accomplishing a strategic objective or a series of strategic objectives within a specified time frame or market. Campaigning is opportunistic, not deterministic, planning; it enables an organization to move quickly in response to a changing environment. Campaigning is inherently flexible, enabling a leader to seize and maintain the initiative by setting the terms for confrontation as opposed to reacting to terms and conditions created by others. The journey to the future is such a campaign or series of campaigns. Like political or military campaigns, it links strategic objectives to achieve the vision; it is structured to integrate and synchronize the means; and, while never ambiguous in its intent, it accommodates uncertainty by its inherent flexibility.

For a campaign plan to have real substance, it must include (1) a clearly stated and well-understood intent, (2) a clear concept, (3) an orientation articulated as a strategic objective or series of objectives, (4) identified resources, (5) a mechanism to integrate and synchronize the plan’s execution, and (6) branches and sequels that will enhance the plan’s flexibility. The campaign plan lays this out in terms of the basic competencies or processes of the organization. Thus, applied to a business, the campaign may have a product development dimension, a marketing dimension, a logistics dimension, a financial dimension, and so on. The campaign plan may be supported by analysis and financial projections, but it is the ideas behind these elements—not the numbers—that are its essence.

What do we want to accomplish? (intent)

What are we going to focus on? (concept)

What steps are we going to take? (objectives)

How are we going to pull it all together? (integration and synchronization)

What do we do next? (branches and sequels)

The intent translates the vision into very specific terms that can guide your actions. In articulating the intent, the leader stretches the organization, both pushing and pulling toward success. It is important to understand that intent seldom leads directly to realization of the vision but carries the organization in the direction of the vision. Achieving the vision will generally be the result of several simultaneous or sequential campaigns. For example, in World War II, Churchill and Roosevelt shared a vision of the unconditional surrender of the Axis powers. Eisenhower’s campaign to liberate central Europe was only one part of that, along with operations in the Mediterranean, on the eastern front, in the Pacific, in the China-Burma-India theater, in the North Atlantic, and elsewhere. Eisenhower’s campaign in the European Theater of Operations was necessary to the accomplishment of the grand strategic vision, but not sufficient.

The most important part of the plan is the concept, because, in the concept, the leader describes how he or she visualizes the campaign unfolding. In the concept, the leader explains how he or she will mobilize and deploy the means of dominating the enemy, the competitor, the market, or whatever. It describes what the staff and subordinate elements are to accomplish, identifies the main effort, and prioritizes supporting efforts. Finally, the leader describes how he or she sees the elements of the campaign coming together.

At its essence, the concept orients the organization on what military theorists describe as the enemy’s “center of gravity,” defined in Fm 100-5, “Operations,” as the “hub of all power and movement upon which everything depends. It is that characteristic, capability, or location from which the enemy…forces derive their freedom of action, physical strength, or will to fight. Several traditional examples include the mass of the enemy army, the enemy’s battle command structure, public opinion, national will, and an alliance or coalition structure.”2

“Center of gravity” is a nineteenth-century idea couched in nineteenth-century terms. But it leads one to think about one’s sources of strength and weakness relative to the opposition’s. You must ask yourself “What must I accomplish to trip the scales overwhelmingly in my favor so that I can win?” The answer might be development of a new process or distribution channel that establishes a new standard of performance, thus superannuating the present ones. For example, when Henry Ford set out to create Ford Motor Company, the center of gravity was producing inexpensive, simple automobiles. When Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak set out to develop a market for personal computers, the center of gravity was making a user-friendly machine. When Sam Walton set out to revolutionize discount retailing, the center of gravity was distribution, which he solved by his innovative cross-docking warehouses and by demanding alliances with suppliers. Just as military commanders must appreciate the enemy and friendly situations and the relative strengths and weaknesses of each, so must an organization understand how it will transform the nature of its competitive environment. The answer to this question becomes the focal point of the concept.

The objectives define the path to successful execution of the campaign as a series of specific major actions to be accomplished. Objectives should be quantified and, therefore, measurable. To return to the World War II example, Eisenhower’s concept was to attack across the English Channel into France, break out of his initial lodgment, conduct a supporting attack through the South of France, and then attack through France and the Low Countries into Germany on two axes—Montgomery on the left, in the North; Bradley on the right—to destroy the German Army, occupy Germany, and link up with the advancing Red Army. His strategic objectives followed his concept: invasion and lodgment in Normandy, breakout into France, opening of the Channel ports, liberation of Paris, and so forth. His objectives gave him a basis on which to constantly adjust his plan, using branches and sequels to optimize its execution. The concept is the leader’s visualization of the campaign; the objectives give him his point-to-point orientation.

The campaign plan must identify the resources to be used. Resources include the people, money, and time that are allocated to the campaign, including “reserves” that are earmarked for use if needed to exploit success or avert failure. More important, however, are critical capabilities, or competencies that give you an asymmetric advantage: the speed with which you can deploy into the targeted market, superior quality, technological leadership, unique customer service, or some other advantageous capability that you possess. Asymmetric advantage facilitates taking an indirect approach: not simply slugging it out head to head for smaller and smaller margins but establishing a wholly new future basis for competing, a basis on which you are dominant. By exploiting your unique competencies, you can control the conditions of the campaign and gain and retain the initiative.

We can see the application of asymmetric resources in the campaigns for the North American automobile market in the 1980s. The Japanese companies’ asymmetric advantage was what James Womack and his coauthors called “lean production” in their book The Machine That Changed the World. Striking a balance between craft and mass production by organizing production around multi-skilled teams that were networked from supplier to production to market gave the Japanese increasing quality at decreasing costs and enabled them to be more responsive to the market. Thus, Japanese automakers could produce an attractive, high-quality automobile and deliver it to the North American consumer at a lower price than could Detroit. As the campaign played out, the U.S. Big Three automakers responded, under pressure, with their own versions of lean production—Team Taurus, the Saturn project, and Chrysler’s Technology Center—neutralizing the asymmetry (essentially creating a new symmetry), but only after the whole marketplace shifted dramatically.

Some portion of total resources should be held in reserve to be employed only as the situation develops or as a need arises. The reserve is a hedge against uncertainty. Reserve resources give a leader the flexibility to sustain the initiative, to reinforce success, or to prevent defeat. There is a tendency in planning to disregard the need to retain a reserve, to want to use all available resources all the time. Planners should recognize that reserve resources are committed resources and provide accordingly. Examples of retained reserves would be financial resources, including unused credit lines; surge production capability; resources being used on lower-priority projects that could be diverted; skilled people who could be used to “pile on” at a critical point; even extra time that can be allocated to let a campaign mature more satisfactorily.

The issue in controlling the plan is not managing day-to-day execution, which should be delegated, but rather monitoring, so that the plan can be adjusted from the strategic level. At that level, the leader must perform two functions. First, he must integrate and synchronize the actions taken. Integration is the arranging of events so that they support one another effectively, making everything fit together; synchronization is the arranging of events so that their effect is massed at the critical point, making everything happen at the most advantageous point and time.

The leader’s other major function in providing strategic direction during execution is modifying the plan as it unfolds, primarily through branches and sequels. “Making it up as one goes along” is not good enough. Nor is a process of constant tinkering or successive approximation. But carefully timed options, built into the concept, give flexibility and balance to the campaign. Branches are options built into the basic plan to anticipate situations that could alter the plan or the outcome. Sequels are subsequent actions based on possible outcomes. Branches address the “What if?” questions; sequels address the “What next?” questions. Neither needs to be robustly developed during planning: what counts is not the level of detail but rather the depth of thought. Branches and sequels may involve the employment of reserve resources, or they may simply involve the redirection of resources already employed.

Richard Pascale, in his assessment of transformation at Ford in the 1980s, tells this story of the Taurus project:

Planning had projected gasoline prices of $3 40 per gallon for the late eighties, and Taurus’ configuration was based on that assumption. By spring 1981, fuel price projections were converging on $1.50 per gallon. Did the revised projections point toward the feasibility of a larger car?

‥ Discarding an entire year’s work, the team increased Taurus’ wheel base, upped capacity from five to six passengers, widened its tread, and shifted from a four-cylinder engine to a V-6. In the circumscribed world of car design, this is like telling the carpenter you want a new kitchen in the place he’s halfway through remodeling as a bathroom. Yet Ford was agile enough to make this shift and still meet Taurus’ targeted introduction deadline.3

As we see, a fundamental assumption of the Taurus campaign plan failed, creating opportunity: Ford was learning even as it was executing. The campaign continued but shifted to a branch—a larger configuration—leading to the most successful new-car launch in the modern history of the automobile industry.

Sequels give you flexibility once you obtain a strategic objective. The campaign plan, for example, may call for a given level of market penetration within a specific period of time. If that objective is achieved more easily or more quickly than anticipated, preplanned sequels can help a leader exploit success by pressing toward a greater share, shifting resources to another market segment, or simply consolidating on the objective to build a more sustainable position. Thinking through sequels early in the campaign-planning process gives the leadership team immediate options for exploiting success. The epitaph for too many successful plans that ended up going no farther than the first major objective is “No one was more surprised than we were.”

When the Army began its experiments in using information technology to create a common situational awareness, each experiment—each objective in the campaign—was designed with follow-on experiments in mind: sequels. When we reviewed the results, we always had options: stopping and redirecting our effort, going back and refining our results, or going on to a more complex experiment. This gave us a degree of control over the journey; it was not a process of random discovery but rather of structured learning.

Timing of the employment of branches and sequels is controlled by using trigger points. A trigger point is a set of conditions for making a decision. The most obvious are decision sets built around the assumptions in your plan; others are based on the actions of your competitor or a major shift in the strategic environment. In the first case, you begin by identifying the critical assumptions in your plan, the assumptions that must hold up if your concept is to hold up. In the Taurus case, one key assumption was high gasoline prices, which made smaller cars desirable. Had Ford persisted in building Taurus as a small-car entry, it is unlikely it would have captured the imagination of the market as it did. As another example, if one of your objectives is to open a new international market, you will need to make assumptions about the regulatory and legal climate in the relevant country. In your planning, you should identify indicators that these assumptions may be incorrect. If those indicators appear, you have a trigger point based on a discrete decision set. Your options then may be, for example, to step up your efforts to accommodate the host nation’s concerns, to emphasize the benefits the host country will derive from your investment, to back away from your investment altogether, or to seek a strategic in-country alliance that would shift your legal and regulatory posture. It is possible to “war-game” these kinds of eventualities in such a way that you will be able to see them coming more clearly and respond more quickly, before they reach crisis proportions.

The second kind of decision set associated with trigger points for branches and sequels involves strategic “counter-counter” moves. You do “A”; your competitor responds with “B,” “C,” or “D.” Your trigger point should be structured to identify the critical information that will tell you, as early as possible, which option your competitor has taken so that you can make your next move against its relative weakness, not its strength. Even if your competitor responds with “None of the above,” this kind of analysis will leave you in a better posture to respond. Trigger points create a focus for control from the strategic level and give you a rational basis for initiating branches or sequels.

Trigger points should not be set on autopilot. Their purpose is not to preset your responses. Trigger points are sets of conditions that might lead you to shift the campaign plan one way or another. The important word in that sentence is “might.” Trigger points keep “What is happening?” in context. Leadership teams that have learned to work using trigger points are invariably able to react faster than teams that wait for things to develop. Even in situations where there is no trigger already established, a leadership team trained to think and act in anticipation will outperform a team conditioned only to react.

The Army’s VII Corps, nicknamed the “Jayhawk Corps,” was headquartered in Stuttgart, Germany, throughout most of the Cold War. By 1990, it had been picked for inactivation as part of the Army’s downsizing campaign, although public announcement had been withheld because the actual inactivation date was envisioned for 1992 or even later. In 1990, the Army went to the Persian Gulf. The unexpected had created an opportunity to overlap the Gulf War campaign and the downsizing campaign. The Army sent VII Corps,with its divisions from Europe, to the Gulf, where, reinforced by units from the United States, then Lieutenant General Fred Franks led it in the largest and most rapid armored assault in our history Immediately on the heels of the Gulf War, the Army inactivated the units and brought the troops and equipment directly back to the United States. In about eight months, the corps had deployed to the Middle East, integrated new units, moved thousands of miles in the most difficult conditions, engaged and defeated a larger force, redeployed, and inactivated. But difficult as it was, it made sense because it all fit into the context of the Army’s ongoing campaigns. Thus the Army actually reduced the turbulence induced by both the war and the downsizing and saved the costs of reestablishing the Jay-hawk Corps in Germany, only to have to take it out a year later.*

The leader alone bears the responsibility for taking risk. But a well-conceived plan, by its very nature, mitigates risk. Branches and sequels provide a means of dealing with the unexpected. But the leader must not assume that a thick and impressive strategic plan, the details of which may be of little value once the execution is under way, will completely eliminate risk.

The leader must structure the plan for success, first by developing a good plan and then by selecting objectives that help to build momentum, sustain the initiative, and demonstrate the strength of the campaign to all its constituents. The initial goals may be relatively modest in absolute terms, but they are nevertheless “strategic” because early success is so important.

Executing the plan is a process of learning that involves the entire leadership team. It requires feedback (including bad news, which never improves with age) and a continual assessment of that feedback so that adjustments can be made as new and better information becomes available.

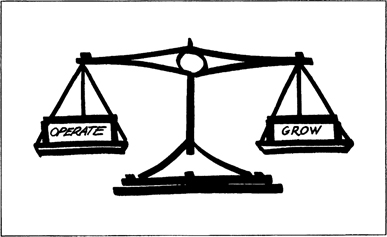

Executing the plan requires a constant trade-off between today and tomorrow. The organization must operate and it must grow—the leader must keep these in balance (Figure 8-1).

Figure 8-1—Balancing Today and Tomorrow Robert E. Lee’s Six-Pounders

The opportunity cost of investing in the future is seldom as apparent as it was for Robert E. Lee in the winter of 1862. Lee was troubled by the fact that the Union artillery was superior to his own. The Union, possessing the preponderance of American ordnance factories, had equipped its force with modern fieldpieces while the South was forced to make do with older models supplemented with what it could purchase overseas, capture on the battlefield, or manufacture in its few foundries. Thus, a year and a half into the war, Lee wrote to the Confederate secretary of war recommending modernization and simultaneously issued instructions to the chief of ordnance to “improve our field artillery.” He wrote, “I have also recommended, should metal be wanted…that our bronze 6-pounder smoothbores and even our bronze 12-pounder howitzers, if necessary, should be recast. This would simplify our field ammunition, save horses, and place our batteries more nearly on an equality with those of the enemy.”4 In other words, he gave up his smaller guns to be melted down and manufactured into better ones. When he began the 1863 campaigns, Lee had a newer and better artillery train. His logistics requirements were reduced, and his firepower was increased. (We can guess that there must have been some long faces as his gunners packed their cannon off to be melted down before the Yankees came back. But Lee knew that the risk of attack in the winter was small. His decision paid off.)

Few leaders will be faced with decisions as difficult as Lee’s, but the same dilemma—balancing today and tomorrow—is faced by leaders every day. How to allocate scarce capital, where to assign people, how to prioritize new products or services, how much to spend on basic research, how to establish resource levels for market development—all are examples of today versus tomorrow. If you put too much emphasis on today, you preordain your tomorrow to being a shallow extension of today. If you put too much emphasis on tomorrow, you undermine the foundation on which tomorrow is built. Overconcern about short-term results can undermine the future. But indifference to short-term results can leave an organization too weak to create the future, no matter how desirable that future may be.

RULE SEVEN: TODAY COMPETES WITH TOMORROW

An organization has only so much energy, so many resources, so many bright people capable of leading. Most of that organizational energy must be focused on today’s requirements—meeting the needs of the market in real time. A certain amount of resistance to any change campaign is not disagreement so much as exhaustion. But the leader knows that some of the resources—time, energy, the best people—must be directed toward the future and that he or she must find a balance between the two.

As Xerox’s CEO, David Kearns led the transformation that brought the company back from near ruin. He became convinced early on that the most pressing strategic issue for Xerox was quality in all of its dimensions, from basic product reliability to customer service. Xerox had rested too long on its laurels as the industry pioneer and was producing an inferior product, causing it to lose badly in the marketplace. In his book Prophets in the Dark, Kearns reflects on an early, two-and-a-half-day meeting at the Xerox Training Center in Leesburg, Virginia, far from corporate headquarters, as a major milestone in the quality revolution that fueled the turnaround. But, he writes:

By no means was there widespread eagerness to attend After all, we were running a nearly $9 billion business while all this was coming up…. A lot of people wondered why we should spend a lot of time and money on a quality program when there was so much to do Some other people saw this as totally incompatible with all the cost-cutting we were engaged in…. There were any number of attempts to get this whole exercise wiped off the calendar “Why do we need this?” someone would ask. “Let’s spend a half day in Stamford [corporate headquarters] and that’ll do it. We’ll go nuts spending two and a half days in Leesburg.”

That kind of resistance is both typical and predictable. Each of the people who attended that meeting had difficult, demanding day-to-day challenges; their today competed directly with their leader’s vision of tomorrow. But Kearns found the essential balance. The meeting was only a step, only the tip of the iceberg of commitment; but it was essential to what is today seen not simply as a successful turnaround but as a successful transformation.5

For each of the Army’s experiments with the future, there were critics who would have spent the money for maintenance or for a conventional training exercise. For every dollar spent to ensure that the skill mix in the smaller force was tailored properly, there were critics who would have “saved” it by slash-and-burn downsizing. For every dollar spent keeping the technology base alive, there were critics who would have bought badly needed trucks or repaired infrastructure. You will face similar criticism of any change effort you launch. In the final analysis, it is leaders who must make the tough calls and balance the demands of today and tomorrow.

*The entire redeployment from Europe, a monumental task tantamount to moving the city of Raleigh, N.C., to California, was performed under the direction of General Crosbie E Saint, then U.S. Army Commander in Chief Europe, whose foresight and planning made possible the movement not only of people and units but also all the Army’s nuclear and chemical weapons and hundreds of thousands of tons of war material stockpiled in Europe, and the closure and return to Germany of hundreds of bases and facilities.