24

PUNDIT TRICK

Gaddi Baithak Palace, Durbar Square, Kathmandu, Nepal

Sir Jack insisted Henrietta return to her apartment while he stayed to guide Green through the diplomatic aftershocks of what they had all witnessed.

“This is a huge mess. My driver will take you home. I suggest we meet for lunch tomorrow. Usual time and place,” he muttered under his breath as he said goodbye. Henrietta didn’t resist. She just nodded in reply, silently wondering if her own presence had in some way conditioned the horrific turn of events. The thought sickened her as Sergeant Rambhadur led her out through a bristling corridor of angry riot police to the car, which immediately joined the slow convoy of diplomatic vehicles exiting the square once she entered.

Alone in the back, Henrietta looked out on the milling, agitated crowd, but saw only the silhouette of the burning man. She shuddered, reminded of that Brocken specter in Quinn’s film. The masked man had also mentioned his name. What does Neil Quinn have to do with all this? she asked herself. He should be back in Kathmandu by now. She needed to see him.

Finally freed from the square, the vehicle began to stretch its new legs to get her home. Even so, however fast the new car went, however dark the night got, Henrietta Richards could feel what she had just witnessed keeping pace with her.

In the past, everything took its time in Kathmandu, even the news. Multiple tides of distorted sweatshop radio, of street corner gossip, of grainy communal television and smudged newsprint were needed to carry a story into every convoluted alley and bare-brick building of that warren of a city. With each retelling, the details would be embellished a little more, the facts as fluid and clouded as the city’s dirty Bagmati River.

Henrietta had made her embassy career out of tracking the flow of information through Kathmandu, trying to assemble it into truth along the way. But even there, in that ancient ramshackle city, things were different now. Events raced ahead of the scheduled media or the ambling tattletale, bouncing from cellphone to cellphone as video, texts, messages, unedited and unfiltered, no time permitted for anything that might slow the process. Despite the geography, the poverty, the matted electrical wiring that toppled down from the forked telegraph poles like black spaghetti, Kathmandu was no less obsessed with the digital than New York or Tokyo.

Henrietta opened her handbag, pushing past the prayer wheel and the skull beads to reach her cellphone. She prided herself on being “old school,” only turning the device on when she needed it, determined not to be its slave, however much she welcomed the mine of information it could access. The cell came to life showing a signal.

It was a Free Tibet demonstration. They’re letting it run for the moment, data-mining, she told herself. It was no secret to her, to anyone in the region, that Chinese corporations had supplied much of the city’s ever-expanding communications network, including that of the Nepal police and the emergency services. It was hardly a great leap forward of imagination to also assume their secret services walked in and out of system back doors as freely as delivery boys, particularly if it had to do with Tibet.

They’ll disrupt the city’s power to suppress the story also, you see.

Power cuts and load shedding were now common in the overpopulated valley and, again, there were rumors they were also being manipulated to cause deliberate disruption.

You’re involved. Be careful—Moscow Rules from now on!

Henrietta instantly turned her phone back off to sidestep the digital and return to the analog espionage that had underwritten her own time at the embassy: those Cold War rules of basic engagement; the whispered conversations and furtive meetings; the stolen papers and tightly folded notes; the celluloid negatives and glossy positives; the drops and pickups; even the strings of beads like those coiled in her handbag.

The coded mala really was one of the oldest tricks in the subcontinent’s spy-book: a standard tool of the first “pundits,” those agents of the British Raj in the nineteenth century. The name was a variation of the word pandit, which means teacher in Hindi. Selected for their education and a swarthy resemblance to Tibetans, famed explorers such as Nain Singh Rawat, Hari Ram, and the enigmatic Kinthup were sent north “beyond the ranges” disguised as wandering holy men or pilgrims, prayer beads in one hand, spinning prayer wheel or wooden staff in the other. However the rosaries of these pretend lamas did not feature the Buddhist spiritual number of one hundred and eight but the profane metric of the ever-approaching West. For every hundred paces the pundit counted off one bead. For every tenth bead they acknowledged half a mile, with every complete rotation of the hundred-bead mala looped in the left hand, five.

At day’s end, with small sextants they furtively mapped the stars and dipped thin-tubed thermometers into their boiling cookpots to record the altitude; they added geographical context to the day’s mala count, their distance traveled. Their findings were then hidden as micro-notes within the small cylindrical drums of their prayer wheels or secret compartments inside their walking sticks. Sometimes they were memorized as never-ending songs or rhymes that were recited like mantra. In this fashion the pundits traveled, measuring and recording those unknown lands beyond the Himalayas, some to finally return to India as experts, others to vanish, imprisoned or killed in some still uncharted place for being the spies that they were.

Yes, the one-hundred-bead mala and the accompanying prayer wheel were about as “old school” as it got. Undoubtedly why she had been given them, Henrietta thought, her handbag tightly closed on her lap as the vehicle sped on. When a motorcycle howled past the SUV to vanish into the Kathmandu night, it made her jump, disturbing her thinking about those two names the masked figure had mentioned and that symbol his sign had displayed.

For a moment it left another image of an older, slower motorcycle laden with two people and chugging its way through those same streets. It had been one of the happiest days of her life and, she reminded herself, the start of it all.

The driver escorted Henrietta to the front door of the old Rana building on Sukhra Path that had been her home ever since it had been converted to apartments in the ’80s. Once inside, she stepped up the stairs to the third floor, moving slowly, weighed down by the burden of what she had witnessed and what her handbag might contain. Entering her apartment, she immediately switched on all the lights and dropped the deadlock behind her. The spring-loaded “snap” guillotined her bright, pristine rooms from the dirty darkness outside.

Henrietta sighed relief at the sound of the lock, and as Bodleian, her black cat, approached, tail raised in hungry greeting. But the cat stopped short, his nose twitching at the unholy smell latched to Henrietta’s clothes, her hair, her skin. Revolted, the cat turned tail and strutted toward the kitchen to await a late supper by way of her apology. Despite being somewhat offended, Henrietta also smelled the vile smoke of the immolation on her clothes now that she was in her spotlessly clean apartment. She agreed that she should indeed shower, change, feed Bodleian, and have a restorative cup of tea before she did anything more; curiosity needed to be kept in check, as her long-lived cat well knew.

Those things done and the tea brewed, Henrietta returned to her living room and switched on her tall standard lamp to further illuminate her favorite reading chair. On a small side table, she readied her cup and saucer, reading spectacles, notebook and fountain pen, her cellphone, a small flashlight, and a silver candlestick with three new candles and a box of matches. Finally sitting down, she placed her handbag on both knees and said to her cat, “Well, here we go.”

Henrietta gently extracted the prayer wheel, raising it into the light. Now that she could really study it, she realized that it was a magnificent piece, as ancient and special as the beads. This was no soda-can replica that could be bought for a few dollars on any Thamel street corner. The detail of the w—

There was a loud click followed by total darkness.

Power cut!

Henrietta felt for the flashlight that she had placed on the side table in anticipation and used its beam to strike a match and quickly light the three-arm candelabra just as she did every time her nighttime studies were similarly interrupted. The flames of the candles rose up to bring out even more exquisite detail in the antique prayer wheel. The cylinder was made of thick hand-beaten copper, finely crafted even if battered by use and tarnished by time. On the outside of the cylinder were raised symbols of silver and gold.

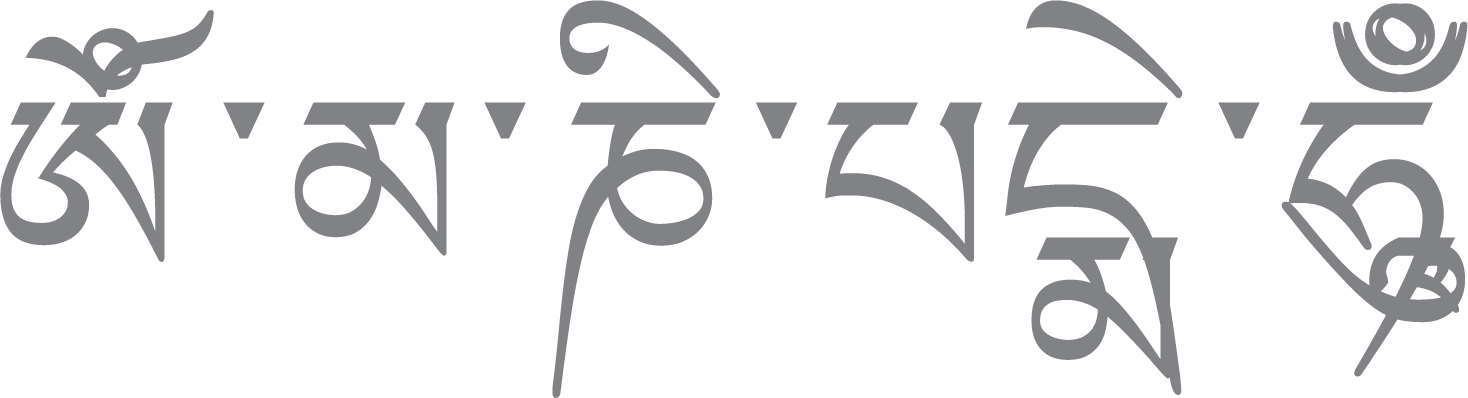

Om mani padme hum, the tireless Buddhist mantra of dedication and supplication.

With the slightest flick of her hand, the wheel began to spin on its wooden axis, the metal weight hanging to one side and lifting to circle like a fat fly on a thread. Gently Henrietta closed her hand around the spinning drum to stop its silent invocations. It was time to see what they were.

On the crown of the prayer wheel a brass acorn nut held the cylinder and its saucer-shaped lid to the axis on which it spun. Grasping the drum of the prayer wheel with her right hand, Henrietta attempted to twist the nut free with her left, but her dry fingers slipped, unable to grip, her hand cramping in arthritic protest.

Slowly getting up from her chair, she took the prayer wheel and the candelabra into the dark of her kitchen, casting a flickering light as she went, reminiscent of Florence Nightingale walking a Crimean hospital ward. There, she set the candelabra down and took a clean cotton tea-towel from a drawer as the distant sound of a police siren split the Kathmandu night, stopping her for an instant as if she was about to commit a crime. When silence returned, Henrietta arranged the cloth to get a better grip on the retaining nut and twisted again using all the strength she could muster, saying to herself slightly sardonically, “Open sesame!”

The stubborn thread held a moment more, then surrendered.

With a hesitant look beyond the candlelight out of the kitchen, Henrietta braced herself for what was about to be revealed. Slowly she turned the nut until it came away within the cotton and she could gently pry the lid from the drum with her other hand.

The lid released with a distinct pulse of pressure, energy that—however she might try and deny it to herself later—traveled up her arms, and ballooned into her head.

A single moth flew out of the drum. Small and brown, starved of light, the insect immediately began to circle the candelabra, fluttering perilously close to its three flames, suddenly spoilt for choice.

With a wave of the towel she shooed it away and looked into the copper cylinder. Surrounding the central axis tube were tightly rolled papers bound by a piece of embroidered cloth and a thin red cord. She extracted the bundle and, removing the red thread, opened the swatch of material and then the two papers held within. She smoothed all three out on her knees.

The contents shocked her, rare tears spiking her blue eyes as an irregular yet urgent beating noise filled the room. Breathless, it took a moment for Henrietta to recognize that it was the sound of her own heart.

To gather her senses, she mandated herself another cup of tea—strong and black this time—then took her flashlight into her bedroom, using the beam to cut and sweep beneath her bed to locate the small metal trunk she hid there. Returning with the black box to the kitchen, she set it on the work surface next to the candelabra, twisted the combination lock to 8-8-4-8, and removed it. The box was a necessary precaution in the event she ever had to leave her home hastily because of fire or earthquake, and its inside was crammed with her most important legal documents and backup CDs of all her climbing records.

She carefully lifted them out to reveal another layer beneath of lesser value, but equally precious to her: a series of old journals, their ragged-edged lokta paper thick with maps, photographs, and postcards. Amongst them was a battered tobacco tin, the lid featuring a fierce khaki mountain set against a black sky printed with the words, “everest rubbed flake.”

Henrietta took out the tin and squeezed it open to reveal a bundle of embroidered patches held by two rubber bands like a stack of old playing cards. Unhooking the bands, she began to deal the woven fabric badges onto the work surface next to the contents of the prayer wheel as if playing Solitaire.

The first line she laid out featured colorful stylized designs, stitched silhouettes of mountains combined with national flags and expedition names.

Everest West Ridge Expedition

Kangchenjunga 8586 m

K2 80

Nanga Parbat International

Makalu North 1981

Glancing at each one, she recalled the times they represented for her and for Christopher Anderson, that name from the past that had accompanied the mala beads and the prayer wheel. Next to each one she placed a journal, his diary of each climb. There was no journal for the last patch. Refusing to let herself dwell on why, she immediately began to lay out another line of badges; simple green cotton rectangles this time, lettered and edged in black that read: ranger; lrrp; airborne; vietnam. Then there were others: brighter, happier, more whimsical; the type you could still buy in the city’s souvenir stores. A multicolored peace sign; those famous all-seeing Buddha eyes that constantly watched over Kathmandu; a square that just said super freak in orange and green on a blue background. Henrietta smiled, choosing to remember that one stitched to a satchel on a ride on the back of an old motorcycle.

The last patch in the tin was the one she was looking for. It too had been hand-embroidered in that Kathmandu sweatshop still located next to her old friend Pashi the barber. The badge was like new, never worn, never used. It was shaped as a moth. The body was red, the four wing segments, blue, yellow, green, and white. In each of the five segments was an individual capital letter, the stitching still tight and bold after all those years.

Henrietta put the piece of material from the prayer wheel on the top of it. That fabric was worn, dirty, and faded, the threads loose and broken but the design was identical. Undeniably it was one of the original batch given out to the small troop of climbers they had worked with to try and help Tibet all those years ago. For a moment it was as if Chris was there with her again as he sketched out the design for the first time; the shape, the colors of the prayer flag, the symbolic letters. Then they were all there once more as he distributed the patches: Piotr the Pole, the Barrett brothers, Paolo Soares, and Fuji. Henrietta had also been given one, hers destined never to grace a battered climbing jacket but to hide in that small tobacco tin of mementos for a lifetime.

The Ghost Moths.

Only her now.

It had only been her for a long time. She had written their damn obituaries, every single one, all those years ago.

Taking up the two papers the old patch had surrounded she studied the first again.

It was a copy of a drawing of a skull set within an inverted triangle, a heavily engraved skull that she realized she had once held in her own hands.

She turned her attention to the second design, a simple line drawing in black and red that showed a mountain. It looked just like a drawing that she had once made.

Christopher Anderson may well have started it all, but the two pieces of paper displayed had finished it. She shuddered at the thought.

With the candelabra, Henrietta walked to her filing cabinet with a heavy heart to open it at M and take out a heavy file marked makalu that she had only just put back following that day’s Lady Huang Hsu interview. She then reached for her atlas. Mount Yudono was a new one, even for her, Henrietta Richards. From the same bookshelf she also retrieved The Deities of Tibetan Buddhism to better place that mask the man had been wearing. For the next hours she read, took notes, and wondered about both the past and the present until she fell asleep in her chair.

The dream was an old one, but familiar. Even the longest roads have their beginning and this, he had told her, had been the start of his, in that small town in the highlands of Colorado.