1

YARTSA GUNBU

Amling, Gyaca, Tibet

Spring in the Year of the Iron Tiger (1950)

Hao Ping’s doors were magnificent, the only thing the village of Amling possessed to rival the ancient monastery that watched over it. It was said that their immense black beams came from the cloud forests of Pemako, the hidden kingdom of poisoners far to the southeast. Their wood was so thick and heavy, others recalled, that it broke the backs of many yaks carrying it over the Su-La, thereby costing the Chinaman an even greater fortune. The villagers firmly believed those great doors were big enough to hold back all the hells, be they hot or cold. But despite such strength and power, qualities the villagers so admired, a simple wooden sign that sometimes hung to their side always received far greater attention.

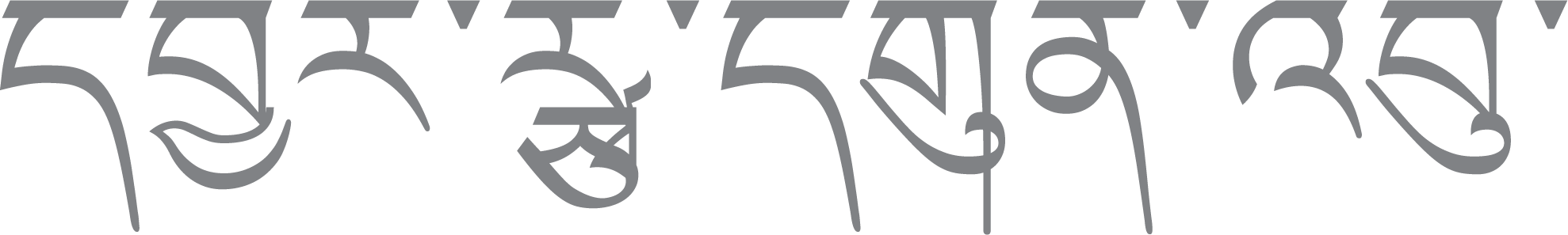

The fading red symbols meant different things to the different people of Amling. To the literate monks who lived in the three-sided monastery that crowned a steep conical hill that rose above the small town, the script read simply, yartsa gunbu.

It was a riddle for a name best explained by their ancient scholar, Geshe Lhalu. Whenever his young novices asked about it, the old monk would patiently pull himself away from his lifetime’s work—his study of the glorious goddess Palden Lhamo, to whom the monastery was dedicated—and extract a piece of dry fungus from his medicine cabinet. Pinching the crinkled stick of ochre between his stained fingertips, his hand would gently lift like a black crane rising on the summer air as he spoke of the summer grass, winter worm.

“A powerful medicine,” he would say, “found especially on the grassy hills below the holy lake of our monastery’s spirit, our protectress, Palden Lhamo. It is one of her many gifts to us, beneficial for ailments of the kidney and the lungs, the heart and the liver.”

The students would be hypnotized by the spiraling crooked fingers raising up what seemed to be a dead caterpillar impaled on a burned matchstick. They always had more questions that Geshe Lhalu would answer by telling the story of a small and drab, yet hardy and determined, insect that flew as briefly as summer lasted in that high place. His wrinkled arthritic hand fluttered before their eyes as their teacher told the story of the ghost moth’s continual battle for survival in that harsh cold land. Then it mimed the coiling action of the moths’ newly hatched caterpillars worming their way into the earth to escape their many predators; the shrike, the owl, the fox, the weasel, and, fiercest of all, the coming winter. But even there, in that cold darkness, seemingly so hidden, so remote, Geshe Lhalu cautioned, the caterpillar was not safe.

For in that very soil, a powdery bane lay waiting to attach itself to the wriggling worm. An infection that would slowly consume its moist life until, finally sensing the arrival of a new spring above, the parasite split open the ill-fated caterpillar’s mummified head to send up a black shoot alongside the new blades of grass to spore on the coming summer air.

“And thus the cycle starts all over again . . . Summer grass, winter worm. As always, in every end, a new beginning . . .” While his suede-headed novices digested this tale of a cruel samsara, Geshe Lhalu’s free hand would silently rise again into a clenched fist like the head-splitting stroma. With a cheeky, toothy smile he would then chuckle and say that Chinese wives had found another most important use for yartsa gunbu that had made Hao Ping rich. That said, the old monk would suddenly flick his crooked index finger up in an instant erection that set the young monks giggling and Dolma, Lhalu’s ever-faithful, ever-present sister monk, blushing.

“Chinamen travel far for the caterpillar fungus of Amling! We need little. They would take it all if they could!”

For the two hundred or so people that inhabited the squat community below the monastery, time and experience rather than literacy had converted the sign’s dagger-like symbols into its own story, wider in interpretation than Geshe Lhalu’s perhaps, but no less accurate. To them, the board’s springtime appearance indicated that Hao Ping, that tiny Chinaman who had lived amongst them for as long as anyone could remember, had put away his opium pipe—his own preferred manner of sitting out the winter—and was ready to do business. The high passes would soon be open to permit the trade caravans to arrive.

Originally the sign, when it was new, said to them in Hao’s spiky birdlike writing, “Bring me all the yartsa gunbu you can find. I will trade for it.” But now, so many years later, that battered plank also silently asked for fox fur, yak tail, musk, wool, deer horn, quartz, even those tiny flecks of gold the villagers sometimes found in the wide river. Hao Ping, like seasoned middlemen the world over, had diversified, and those great doors had been built for good reason: to protect the huge courtyard that received the caravans, the silk-lined salon where business was transacted and celebrated, and those dark storerooms that, every year, became crammed with precious goods for barter: cigarettes, fabrics, cottons, silver, jewels, coral beads, tools, pots, pans, and most important, tea. Amling needed few staples. Barley, the villagers grew in the walled fields beyond the river. Butter, they churned from the milk of their yak that roamed the hillsides. Salt, they found large pink crystals of in a cave a week to the south. However, tea—strong, black tea—had to come from Hao Ping. It arrived at his doors in dense five-pound blocks, embossed with symbols the villagers couldn’t read, to be chiseled and shaved into amounts they understood to the very last grain. Winter in that place lingered long and the tea supplies dwindled, so the painted plank’s reappearance was always a relief. The children of Amling particularly welcomed its arrival. For them, that sign was just one more to accompany the heavy rattle of snowmelt in the river, the green furring of seedlings in the mud of the paddocks, and the honking of newly arrived geese from beyond the mountains that announced winter was over for another year. Their excitement was equally noisy and joyous, even if it also meant long days ahead on the sides of the cold, shadowy flanks of the higher hills, watching sheep and yak and searching on numb hands and knees for those tiny black sticks that poked up through the snow-burned grass. At least, successfully digging that dirty dead worm from the ground offered praise and reward, instead of the heavy hand of punishment that was never more than a few feet away during the cramped confines of winter.

When not on the hill, the kids would wait outside the old Chinaman’s house, wrestling, shooting one another with wooden arrows, racing on imaginary ponies, or teasing the village idiot, Mad Namgi, until he would fly into a rage, to their delight, becoming a screaming whirlwind of dust in the center of the street. All the while they would remain attentive to the comings and goings of their fathers and the traders, listening for the slap of hands and shouts that signaled a deal had been done, awaiting the shower of candies and small toys, fabric animals and rag dolls that would be flung out soon after to encourage the “searchers” further. Whenever a new caravan arrived, the children would study it eagerly to see if those strangely costumed traveling players were with it. They lived for the town’s annual performance of the Warrior Song of King Gesar. It was the event of their summer, and that old wooden sign also announced it was on its way, sooner or later.

Hao Ping’s sign may indeed have been small and simple, old and worn, but it said so many things to so many people. However, that year, its appearance said one more thing that no one could be expected to understand. Life for the monks, the villagers, the children, even old Hao Ping himself, was about to change forever and not even his mighty doors were going to be able to hold that back.