THE SCENE WAS THE livestock pavilion of the University of Wisconsin. The time was late April 1938. Under a huge banner emblazoned with a circle around a cross, a slim, gray-haired man with a boyish face was orating before a rapt audience of several thousand. Football players sporting huge W’s patrolled the aisles. The speaker was Governor Philip La Follette of Wisconsin, scion of the great Fighting Bob, brother of young Senator Bob. The occasion was the launching of a new party, National Progressives of America.

By the time La Follette finished, hair tousled and coat awry, reporters were sure that history had been made—perhaps even to the degree it had been at Ripon, Wisconsin, eighty-four years before, when the Republican party was founded. The young Progressive, they said to one another, had hit Roosevelt where it hurt. He had scored New Deal economics and New Deal politics at their weakest points. For ten years, according to La Follette, “the Republicans and the Democrats have been fumbling the ball.” The people had had enough of relief and spoon feeding and scarcity economics. They wanted jobs and security. The new party would be no popular front, “no conglomeration of conflicting, opposing forces huddled together for temporary expediency.” It was an obvious fling at Roosevelt and his personal coalition. How would the New Deal’s chief respond?

The President, it seemed, was inclined to scoff. While the crowd was carried away with the enthusiasm of the moment, he wrote Ambassador William Phillips in Rome, most people seemed to think La Follette’s new emblem was just a feeble imitation of the swastika. “All that remains is for some major party to adopt a new form of arm salute. I have suggested the raising of both arms above the head, followed by a bow from the waist. At least this will be good for people’s figures!”

Actually Roosevelt had mixed feelings toward the new party. He knew that La Follette had planned his move carefully, with assiduous cultivation of farm and labor leaders. The movement could not be dismissed. Roosevelt hoped, though, that it might serve as a useful warning to conservative Democrats that their party was in danger of losing liberal support. Everything depended on Phil and Bob not going too far. To keep them from going too far, Roosevelt told Ickes, he would invite Bob on a Potomac cruise; he would suggest to the Senator that after 1940 he could have the secretaryship of state, and Phil could take his place in the Senate.

It was a typical Rooseveltian stratagem, but it seemed too late for stratagems. Phil went serenely ahead, courting progressive groups and third-party leaders throughout the northern Central states. Nor did his efforts have any discernible influence as a warning to conservative Democrats. In Congress, which adjourned in mid-June, they kept on jabbing and thundering against the New Deal. Aside from the spending bill, the chief accomplishments of the Seventy-fifth Congress had been the revived agricultural program for farmers and the weak wage-hour bill for workers. A new housing program had been authorized, but one that would hardly touch the mass of the “ill-housed.” The New Deal, as a program for the general welfare, had been little advanced—certainly not when compared with the glowing promises of January 1937.

Slowly Roosevelt came to his decision—the time had come for a party showdown.

The idea of purging the party of conservative congressmen was not a new one. For months at the White House there had been talk of a purge, especially on the part of Corcoran, Ickes, and Hopkins. But the fact that Roosevelt could embrace this ultimate weapon was a measure of his true feelings in the spring of 1938. Not only was a purge directly contrary to the President’s general first-term policy of noninterference in local elections, but even more, it forced him into the posture he hated most—the posture of direct, open hostilities against men who were in his party and some of whom were his friends, of almost complete commitment to a specific method and a definite conception of party.

Only resentment and exasperation of the greatest intensity could have moved Roosevelt to such action, and that was his state of mind in the spring of 1938. Despite his usual surface geniality, for months he had simmered and stewed over the obstructionists who were gutting his program. Again and again in the presence of intimates and even of visitors he struck out at his foes—at the lobbyists who tried to exempt special interests from regulation, at the “yes but fellows” who piously agreed with the need for reform but never agreed with Roosevelt’s way of doing it, at the millionaires who found legal devices to avoid taxes, at the columnists and commentators who told lies to scare the people, at the “fat cat” newspaper publishers who ganged up on the administration, and, above all, at the congressmen who had ridden into power on his coattails and now were sabotaging his program.

In a free society, only the last of these were within reach of presidential retaliation. As La Follette fished in troubled political waters and threatened to split the Grand Coalition in June 1938, Roosevelt decided to act.

On a hot night late in June the President fired the opening salvo. In a fireside chat he stated that the Seventy-fifth Congress, elected on a “platform uncompromisingly liberal,” had left many things undone. On the other hand, he said, it had done more for the country than any Congress during the 1920’s, and he listed a number of its achievements. People had urged him to coast along, enjoy an easy presidency for four years, and not take the party platform too seriously.

“Never in our lifetime has such a concerted campaign of defeatism been thrown at the heads of the President and Senators and Congressmen” as in the case of this Congress. “Never before have we had so many Copperheads” who, as in the War between the States, wanted peace at any price. The President dwelt for a moment on the economic situation. Leaders of business, of labor, and of government had all made mistakes, he asserted. Government’s mistake, however, was in failing to pass the farm and wage-hour bills earlier, and in assuming that labor and capital would not make mistakes.

Then Roosevelt got down to the business at hand. The issue in the congressional primaries and elections, he said, was between liberals who saw that new conditions called for new remedies, including government action, and conservatives, who believed that individual initiative and private philanthropy would solve the country’s problems and who wanted to return to the kind of government America had had in the 1920’s.

“As President of the United States, I am not asking the voters of the country to vote for Democrats next November as opposed to Republicans or members of any other party. Nor am I, as President, taking part in Democratic primaries.

“As the head of the Democratic Party, however, charged with the responsibility of the definitely liberal declaration of principles set forth in the 1936 Democratic platform, I feel that I have every right to speak in those few instances where there may be a clear issue between candidates for a Democratic nomination involving these principles, or involving a clear misuse of my own name.

“Do not misunderstand me. I certainly would not indicate a preference in a State primary merely because a candidate, otherwise liberal in outlook, had conscientiously differed with me on any single issue. I should be far more concerned with the general attitude of a candidate toward present day problems and his own inward desire to get practical needs attended to in a practical way.” And again the President struck out at “yes but fellows.”

ROOSEVELT DECLARES WAR ON PARTY REBELS, read the next day’s headlines. Yet the declaration of war was an ambiguous one. Politicians anxiously questioned one another. What was the President’s test of a conservative? Was it only a vote against the court plan? Would Roosevelt limit himself to speaking out? And what did he mean by his statement that he was acting as party leader rather than as President?

Confusion deepened after Roosevelt left Washington in his air-cooled, ten-car train that would take him on a zigzag route across the nation. Roosevelt seemed to have a different tactic in each state. In Ohio he gave a mild nod of approval to a mild New Dealer, Senator Robert J. Bulkley, who had a primary fight on his hands. In Kentucky the President pulled no punches. Alben Barkley, his stalwart Senate leader, was hard pressed by Governor “Happy” Chandler, who had a big grin, a rousing platform manner, and a firm grip on his political machine. Roosevelt was so eager for Barkley to win and so worried that a defeat would mean Senator Pat Harrison’s capture of the Senate leadership that he had even welcomed John L. Lewis’s proffer of aid in the race.

Greeting Roosevelt’s train, Happy deftly slid into a place next to the President in the parade car and took more than his share of the bows, while Barkley smoldered and Roosevelt showed his usual sang-froid. Happy soon got his comeuppance. In a speech showering Barkley with praise the President dismissed Chandler as a young man who would take many years to achieve the experience and knowledge of Alben Barkley. “Any time the President can’t knock you out, you’re all right,” said the irrepressible Happy, who was determined to keep at least a thumb hooked into the President’s coattails. But a few hours later Roosevelt shook even the thumb loose by hinting that Chandler had proposed to the White House a deal in judicial appointments in order to get to the Senate.

Having spoken like a lion, the President moved as stealthily as a fox during his next stops. In Oklahoma he mentioned his “old friend” Senator Elmer Thomas but he did not snub Thomas’ primary opponent. In Texas he smiled on several liberal congressmen, including Lyndon Johnson and Maury Maverick, and he threw Senator Connally, a foe of the court bill, into an icy rage by announcing from the back platform the appointment to a federal judgeship of a Texan whom Connally had not recommended. In Colorado another court bill opponent, Senator Alva Adams, shifted uneasily from foot to foot while the President elaborately ignored him. But Adams’ opponent, who had seemingly launched his campaign with White House blessing, was also ignored. So was Senator Pat McCarran in Nevada, though the agile Pat managed to thrust himself into the Rooseveltian limelight. In California the President mentioned his “old friend” Senator McAdoo, but the situation was topsy-turvy there, for McAdoo’s opponent was no tory but a leader of the “$30 every Thursday” movement named Sheridan Downey.

By the time the President had been piped aboard the Houston, had made a long sea cruise down through the Panama Canal to Pensacola, and had started back to Washington, some of the primary results were in. Roosevelt could feel well satisfied. Barkley won decisively in Kentucky, as did Thomas in Oklahoma. To be sure, Adams won in Colorado and McCarran was running strong in Nevada, but Roosevelt had not deeply committed himself in these races.

Moreover, the trip across the country had been one more parade of triumph for the President. In Marietta, Ohio, a little old woman symbolized much of the popular feeling when she knelt down and reverently patted the dust where he had left a footprint. The enthusiasm of the crowds bore out the comment of Republican Congressman Bruce Barton that the feeling of the masses toward Roosevelt was the controlling political influence of the time. And Roosevelt’s triumph had been a wholly personal one. Farley, who had publicly supported the President after the fireside chat while secretly deploring the purge, was in Alaska. Garner had not met the President in Texas. Editorials deplored the President’s meddling in local elections. Cartoonists pictured him as a donkey rider, a club wielder, a pants kicker, a big-game hunter.

Emboldened by his successes, Roosevelt on his way north turned his attention to his number-one target, the doughty and influential Senator Walter George of Georgia. The scene was so dramatic it seemed almost staged. Sitting on the platform with Roosevelt in the little country town of Barnesville was George himself, Lawrence Camp, a diffident young attorney whom the administration had induced to run against the Senator, and a host of nervous Georgia politicians. From the moment he started talking Roosevelt’s heavy deliberateness of tone and manner seemed a portent. After dwelling on his many years at Warm Springs, the problems facing the South, and the need for political leadership along liberal lines, Roosevelt turned to the business at hand. He said of George:

“Let me make it clear that he is, and I hope always will be, my personal friend. He is beyond question, beyond any possible question, a gentleman and a scholar.…” But he and George simply did not speak the same political language. The test was in the answer to two questions: “First, has the record of the candidate shown, while differing perhaps in details, a constant active fighting attitude in favor of the broad objectives of the party and of the Government as they are constituted today; and secondly, does the candidate really, in his heart, deep down in his heart, believe in those objectives?

“I regret that in the case of my friend, Senator George, I cannot honestly answer either of these questions in the affirmative.” A faint chorus of mixed cheers and boos rose from the crowd. George stirred uneasily; Camp sat motionless.

There was more in the speech, as Roosevelt dismissed another candidate, red-gallused, hard-faced, ex-Governor Eugene Talmadge, as a man of panaceas and promises, and roundly praised Camp. But the climax for the crowd came as Roosevelt turned to George and shook hands.

“Mr. President,” said the Senator, “I want you to know that I accept the challenge.”

“Let’s always be friends,” Roosevelt replied cheerily.

Next state up was South Carolina, the domain of Cotton Ed Smith. Again Roosevelt displayed his versatility. Smith’s opponent, Governor Olin D. Johnston, had launched his campaign in Washington directly after a talk with the President, but now Roosevelt took a subtle approach. Without mentioning Smith by name, he ended a talk in Greenville with the remark, “I don’t believe any family or man can live on fifty cents a day—” a fling at Cotton Ed, who was reputed to have said that in South Carolina a man could.

Back in Washington, the President struck the hardest blow of all against his old adversary, the urbane Millard Tydings of Maryland. At a press conference he accused Tydings—and he told reporters to put this in direct quotes—of wanting to run “with the Roosevelt prestige and the money of his conservative Republican friends both on his side.” He lined up Maryland politicians behind Tydings’ primary opponent, Representative David J. Lewis. He asked former Ambassador to Italy Breckinridge Long, a political leader in the state, to help out financially and personally. And he stumped intensively in Maryland for two days against Tydings during the first week of September. To give his campaign a semblance of party backing, the President got Farley to go with him. The Democratic chairman glumly watched the proceedings. “It’s a bust,” he told reporters.

A bust it was. During the next weeks Roosevelt’s political fortunes reached the lowest point of his presidency.

Smith won decisively in South Carolina. Tydings won by a huge vote in Maryland. Maverick and other Roosevelt men lost in Texas. George came out far in front in Georgia. Talmadge was second, and Camp an ignominious third. Semi- or anti-New Dealers Alva Adams of Colorado, Pat McCarran of Nevada, Augustine Lonergan of Connecticut, all won. “It takes a long, long time to bring the past up to the present,” Roosevelt remarked after Smith’s victory.

Only one bright spot relieved the dark picture. Earlier in the year Hopkins and Corcoran had induced James H. Fay to enter the primary in Manhattan against the hated John O’Connor, who had used his chairmanship of the Rules Committee to thwart the President. Fay was a good choice: he had impeccable Irish antecedents, a war record, and close ties with a number of Tammany chiefs. Hopkins lined up Labor party support for Fay through La Guardia, and Roosevelt agreed to ask Patterson of the Daily News to back the New Deal candidate. Corcoran spent a month in New York running the campaign at the ward and precinct level. When O’Connor began to fight back hard to save his political life, Roosevelt got a reluctant Boss Flynn to help run Fay’s campaign. These combined efforts defeated O’Connor by a close vote in mid-September.

By now Democrats and Republicans were locked in battle in hundreds of congressional and a score or two senatorial races. Wracked by internal splits, the Democrats had to face the somber likelihood that they would suffer a drop after the sweep of ‘36. The Republicans, knowing they had seen the worst and enjoying the brawls in the enemy camp, were jubilant. Some of them, indeed, were cocky to the point of insolence. Backers of a Republican candidate in Wisconsin wired Roosevelt urging him to come to Wisconsin and oppose their man. The President’s opposition, they added, would guarantee his election.

Roosevelt ignored such antics, but he could not ignore the strange directions the campaigns were taking. A shift had taken place in the spirit and temper of the people. In many races the issues were not the standard old reliables like prosperity, security, reform, and peace, but vague and fearsome things such as state rights, the “rubber-stamp” Congress, presidential power, the purge itself. In other races candidates for Congress got embroiled in local issues. In South Carolina, for example, Cotton Ed raised the banner of white supremacy, and Johnston, not to be outdone, accused Smith himself of once “voting to let a big buck nigger sit next to your wife or daughter on a train.” In Pennsylvania the main issue was not the New Deal but corruption; in Michigan, the sit-down strikes; in California, a state pension plan.

As party leader Roosevelt presumably had some power of campaign direction. But unlike his own presidential campaigns, where he could exploit his unmatched skill at focusing issues and at timing the attack, he lacked control over the situation. Instead of his running the campaigns, the campaigns ran away with him.

He had to spend a good deal of time simply making his position clear. In the last weeks of the campaign he found it necessary to defend Governor Frank Murphy of Michigan against charges that he had treasonably mishandled the sit-down strikes; he had to rebuke Pennsylvania Republicans for charging that he had kept hands off that state because of distaste for the Democrats there; he had to make clear that his silence about Governor Elmer Benson of Minnesota did not mean he was not in favor of Benson; he had to declare his support in California for Downey, victor over McAdoo, as a real liberal, despite Downey’s “$30 every Thursday” plank, which Roosevelt opposed; he had to make clear his support of Senator F. Ryan Duffy in Wisconsin; and he had to declare for Governor Lehman and Senator Wagner of New York, candidates for re-election. Putting out campaign brush fires all over the country was no way to leave the President in a commanding position.

On election eve Roosevelt tried to pull the confused situation into focus. He reasserted that the supreme issue was the continuation of the New Deal. After a homely reference to the “dream house” he was building in Hyde Park, he said that a social gain, unlike a house, was not necessarily permanent. The great gains of Theodore Roosevelt and of Wilson, he warned, had evaporated during the subsequent administrations. The President thrust a barbed lance at the opposition. “As of today, Fascism and Communism—and old-line Tory Republicanism—are not threats to the continuation of our form of government. But I venture the challenging statement that if American democracy ceases to move forward as a living force … then Fascism and Communism, aided, unconsciously perhaps, by old-line Tory Republicanism, will grow in strength in our land.” But political exigencies forced Roosevelt even on a national hookup to devote much of his speech to New York candidates.

The election returns dealt the Democrats a worse blow than Roosevelt had expected. Republican strength in the House almost doubled, rising from 88 to 170, and increased in the Senate by eight. The Republicans lost not a single seat. The liberal bloc in the House was halved. Wagner and Lehman both won in New York, but a brilliant and personable young district attorney, Thomas E. Dewey, came so close to upsetting Lehman that the challenger became a prospect for his party’s presidential nomination in 1940. Winning over a dozen governorships, the Republicans offered new faces to the nation—Leverett Saltonstall in Massachusetts, John Bricker in Ohio, Harold Stassen in Minnesota. Taft beat Bulkley in Ohio and took over a Senate seat that he would soon convert into a national rostrum. Philip La Follette lost in Wisconsin, Murphy in Michigan, Earle in Pennsylvania.

Roosevelt tried to make the best of the situation. The New Deal had not been repudiated, he told friends. The trouble lay in party factionalism and local conditions. He pointed to corruption in Massachusetts, a race-track scandal in Rhode Island, a parkway squabble in Connecticut, Boss Frank Hague’s dictatorial ways in Jersey City, strikes in the Midwest, poor Democratic candidates elsewhere. The President could point to the fact that, after all, his party still held big majorities in both Houses of Congress. But could he blink the fact that Republicans combined with anti-New Deal Democrats could control the legislature?

“Will you not encounter coalition opposition?” a reporter asked him at the first press conference after the election.

“No, I don’t think so,” the President answered.

“I do!” his questioner came back pertly, amid laughter.

“The trees are too close to the forest,” Roosevelt went on enigmatically.

The reporter was right, and Roosevelt knew that he was right. The Republicans were making no secret of their plans to besiege the New Deal through the conservative Democrats in Congress. But the President had an eye on the forest too. The critical situation in Europe would force a political reordering at home. And he knew he would have strong cards to play against the conservatives in 1940. Meantime he showed his cheerful visage to the world. He even jested about the visage that some newspapers had given him.

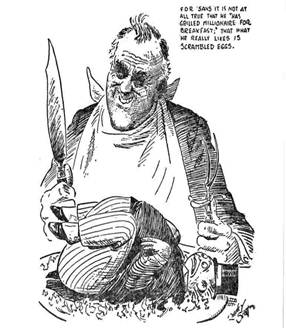

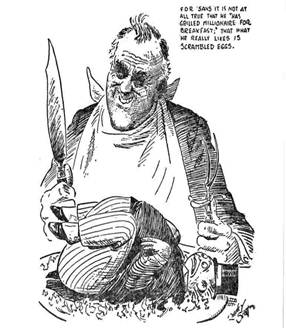

“You undergraduates who see me for the first time,” he told a delighted student audience at Chapel Hill in December, “have read your newspapers and heard on the air that I am, at the very least, an ogre—a consorter with Communists, a destroyer of the rich, a breaker of our ancient traditions. Some of you think of me perhaps as the inventor of the economic royalist, of the wicked utilities, of the money changers of the Temple. You have heard for six years that I was about to plunge the Nation into war; that you and your little brothers would be sent to the bloody fields of battle in Europe; that I was driving the Nation into bankruptcy; and that I breakfasted every morning on a dish of ‘grilled millionaire.’ ” The crowd guffawed.

“Actually I am an exceedingly mild mannered person—a practitioner of peace, both domestic and foreign, a believer in the capitalistic system, and for my breakfast a devotee of scrambled eggs.”

Against the advice of Garner and other of his “antediluvian friends” in Congress, as he called them, Roosevelt stood firm on his New Deal policies. Before the legislators in January 1939, he defended his program of social and economic reform. To be sure, he justified that program partly as an aid to national defense, and he stated that the country had “passed the period of internal conflict in the launching of our program of social reform.” But he went on to call for the releasing of the nation’s full energies “to invigorate the processes of recovery in order to preserve our reforms, and to give every man and woman who wants to work a real job at a living wage.” And he called again for the measures Congress had denied him the year before, including reorganization.

Another Myth Exploded

Dec. 6, 1938, Quincy Scott, Portland Oregonian.

Nor did Roosevelt indicate any compromise in a fighting party speech he gave to a Jackson Day dinner a few days later. He welcomed the return of the Republicans to a position where they could no longer excuse themselves for not having a program on the ground they had too few votes. He charged that during recent years “Republican impotence has caused powerful interests, opposed to genuine democracy, to push their way into the Democratic party, hoping to paralyze it by dividing its councils.” He called on Democrats to stick together and to line up with those from other parties and with independents in a firm alliance. He prophesied that the Republican leadership, conservative at heart, would “still seek to run with the hare and hunt with the hounds, talking of balanced budgets out of one side of its mouth and in favor of opportunist raids on the Treasury out of the other.” And he appealed to the memory of Andrew Jackson to keep the party a liberal party, not a Democratic Tweedledum to a Republican Tweedledee.

The President’s major appointments reflected his tenacity of purpose. To the consternation of the business community Hopkins succeeded Roper as Secretary of Commerce. The priestlike Murphy of Michigan took Cummings’ place as Attorney General. Felix Frankfurter, after serving six years as a recruiting sergeant for the New Deal, was appointed to Holmes’s old and Cardozo’s recent seat on the Supreme Court. And William O. Douglas took Brandeis’ place on the high bench. So in the New Deal’s sixth year there were secure liberal majorities in both cabinet and court.

But not in Congress. As the 1939 session got under way, the congressional threat to New Deal programs became more and more apparent.

The conservative coalition on the Hill would not, of course, abolish the New Deal, even if it wished to, for it could not command two-thirds majorities to override Roosevelt’s vetoes. But it could stop the extension of the New Deal into new and controversial fields. To be sure, Congress passed a cut-down reorganization bill, a revised and liberalized social security measure, and several other administration measures. When it came, however, to spending programs aimed at fulfilling the President’s promises of recovery, the legislators balked. Bills to finance self-liquidation projects and to lend eight hundred million dollars on housing projects passed the Senate but failed in the House amidst a general denunciation of the relief program. Relief appropriations, too, were pared sharply.

The inevitable consequence of this political stalemate was economic stalemate. With New Deal reforms secured now by a liberalized court and by determined presidential backing, investors were still immobilized largely by their fears of the government. But Congress would not tolerate a large-scale spending program, even if Roosevelt proposed it. The recovery policy was caught in dead center. Although business conditions had improved markedly since the year before, dead center still meant eight to ten million unemployed.

Some congressmen, however, were not satisfied even with stalemating the New Deal. They sought to dismantle it. And in their attempt they turned to the three classic weapons of congressional usurpation of executive power.

Perhaps the most potent of these weapons was the power to investigate. During Roosevelt’s first term friendly legislators like Senator Black had used this power to arouse public opinion behind New Deal measures. The President was strong enough almost single-handed to balk hostile probes, as in the case of Tydings. But now, in his second term, the situation was reversed. At the start of the 1939 session Garner in a cabinet meeting told Roosevelt bluntly that the opposition was planning to investigate the WPA and other agencies. Something should be done about it, he said. “Jack,” the President answered, “you are talking to eleven people who can’t do anything about it.” It was up to the congressional leaders, including Garner, he said. It was a clear indication of the extent to which Roosevelt’s resources of personal influence had been drained off midway through the second term.

Even in the case of Martin Dies, the square-faced, hulking young Texan who ran the House Un-American Activities Committee, Roosevelt had to act cautiously. He detested Dies’s fishing expeditions and he knew the political dangers in Dies’s jabs at Ickes, Hopkins, Miss Perkins, and other New Dealers as being soft toward Communists. But the President, aside from one indignant press statement, did not risk an open counterattack against his foes. Asked by reporters to comment on the Texan’s charge that Roosevelt was not co-operating with him, the President answered only with an elaborate “Ho hum.” Incensed over Dies’s treatment of witnesses, he protested indirectly to another committee member. When Ickes was ready to cannonade Dies with a speech entitled, “Playing with Loaded Dies,” Early telephoned that the President said, “For God’s sake don’t do it!” Roosevelt hoped he could head Dies off by maneuvering through his leaders on Capitol Hill. But this indirection, which had worked so well during the first term, no longer seemed to turn the trick. Dies got a huge appropriation in 1939 and kept on playing ducks and drakes with the issue of Communism.

A second classic instrument of congressional attack was control over hiring administrative personnel, and here again Congress lived up to tradition. The most obvious of these controls over hiring was the old practice of senatorial courtesy, by which senators agree, in a kind of unwritten mutual defense pact, to hold up any presidential nomination when the nominee is “personally obnoxious”—i.e., a member of a hostile political faction—to one of their colleagues. In January 1939 Roosevelt deliberately flouted the rule by nominating as federal judge a Virginian who was friendly to the governor of that state but not to Senators Glass and Byrd. The President’s nominee was rejected. Angry and public exchanges between Roosevelt and Glass followed, but when the dust settled, senatorial courtesy stood intact.

A third means of congressional control was the legislative power to appropriate funds annually for the bureaucracy. To the extent it dared, the coalition cut down on general funds for agency programs, but it did not dare go too far because even Republicans and anti-New Deal Democrats were sensitive to the reaction of groups benefiting from the programs. What the coalition could and did do was to cut funds for those functions behind which no congressional bloc would rally, but which in the long run might critically influence the durability and impact of the programs— namely, planning, research, statistical and economic analysis, scientific investigation, administrative management, information, staffing.

The heart of the situation was this: By 1939 coalition leaders in Congress had left their defensive posture of ’37 and ’38 and had moved openly to the attack. Where once they had been content to stop the New Deal from expanding, now they were trying to disrupt major federal programs or to divert them to their own purposes. Where once they had fought against presidential control over the legislative branch, now they were extending their own controls over the executive branch.

A chief executive’s power to control his own establishment is always in jeopardy. At best, certain parts of the disheveled and straggling bureaucracy will escape his control if only because of its vast size. Many bureaucrats are holdovers from previous regimes and respond to ideologies and programs of the past. Such officials the President usually can remove if he knows about them; but some of them may be beyond his reach. Early in his first term Roosevelt sacked a holdover commissioner of the Federal Trade Commission mainly because the man was utterly out of sympathy with the New Deal, but the Supreme Court later ruled that his power to remove independent commissioners simply on the grounds that they differed with him over policy depended on Congress. So, too, many officials were less responsive to the change in presidential leadership than they were to the narrow professionalism and traditions of bureaucratic cliques.

Friction within government is inevitable when men are ambitious for themselves and passionately consecrated to their programs, and this was especially true of Roosevelt’s jostling, bickering lieutenants. From the start fierce conflicts swept his top officialdom. The peppery, cantankerous Ickes was a ceaseless generator of friction; he jousted with Hugh Johnson, Morgenthau, Miss Perkins, Hopkins, and others, and his battle with Wallace culminated in a blazing face-to-face quarrel where charges of lying and disloyalty to the President were tossed about. Personal and administrative differences among the three TVA board members became so acute that Roosevelt had to hold long hearings in the White House and, in the end, ousted the chairman. Other rivalries that smoldered under the surface were fair game for newspaper columnists and cocktail party gossips.

Roosevelt’s personality and administrative methods encouraged this turbulence. He delegated power so loosely that bureaucrats found themselves entangled in lines of authority and stepping on one another’s toes. Despite his public disapproval of open brawls, Roosevelt actually tolerated them and sometimes even seemed to enjoy them. He saw some virtues in pitting bureaucrat against bureaucrat in a competitive struggle. The very nature of the New Deal programs with their improvised, experimental, and often contradictory qualities was another source of discord.

Criticism of Roosevelt’s administrative methods waxed during his second term. This criticism buttressed the demands of conservatives for “less government in business, and more business in government.” It was also a handy tool for congressmen bent on extending their own controls over the bureaucrats. But not all close students of the peculiar claims and needs of the American political system agreed with this criticism of Roosevelt as an administrator.

Again and again Roosevelt flouted the central rule of administration that the boss must co-ordinate the men and agencies under him—that he must make a “mesh of things.” But given the situation he faced, Roosevelt had good reasons for his disdain of copybook maxims. For one thing, too much emphasis on rigid organization and channels of responsibility and control might have suffocated the freshness and vitality he loved. His technique of fuzzy delegation, as Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., has said, “often provided a testing of initiative, competence and imagination which produced far better results than playing safe by the book.” Characteristically, Roosevelt himself took the burden of salving the aches and lacerations that resulted from his method of administration.

Disdaining abstract organization, Roosevelt looked at administration in terms of people. It was his sensitivity to people in all their subtle shadings and complexities that stamped him as a genius in government. He impressed them by his incredible knowledge of small details of their job; he invigorated them by his readiness to back them up when the going got rough. Yet he was no sugary dispenser of lavish praise. One of his political lieutenants never got a comment on her work, but she was conscious of “warm, constant, and continuous support and a feeling that he liked me, had confidence in my ideas and was sometimes amused at my ‘goings-on’ as I was myself.”

One reason, then, for Roosevelt’s quixotic direction was that it quickened energies and incited ideas in musty offices of government. But there were other reasons.

UPSIE DAISY!, March 28, 1935, C. K. Berryman, Washington Star

Again and again Roosevelt put into the same office or job men who differed from each other in temperament and viewpoint. He gave Moley and later Welles important State Department tasks that overlapped those of Hull; he divided authority in the NRA between Hugh Johnson and the general counsel, Donald Richberg; he gave his current Secretary of War, Harry Woodring, an assistant secretary who was often at odds with his chief; he gave both Ickes and Hopkins control over public works, both Ickes and Wallace control over conservation and power, both Farley and a variety of other presidential politicians control over patronage and other political functions.

Roosevelt followed this seemingly weird procedure in part because it fell in naturally with his own personality. He disliked being completely committed to any one person. He enjoyed being at the center of attention and action, and the system made him the focus through which the main lines of action radiated. His facility at role-taking enabled him to deal separately with a variety of people at maximum advantage. His administrative methods tended to keep him well informed about administrative politics, too, for his bickering lieutenants were quick to bring him the various aspects of the situation.

The main reason for Roosevelt’s methods, however, involved a tenacious effort to keep control of the executive branch in the face of the centrifugal forces of the American political system. By establishing in an agency one power center that counteracted another, he made each official more dependent on White House support; the President in effect became the necessary ally and partner of each. He lessened bureaucratic tendencies toward self-aggrandizement; he curbed any attempt to gang up on him. He was, in effect, adapting the old method of divide and conquer to his own purposes.

The problem, from Roosevelt’s standpoint, was one of power rather than of narrow efficiency. His technique was curiously like that of Joseph Stalin, who used the overlapping delegation of function, a close student of his methods has said, to prevent “any single chain of command from making major decisions without confronting other arms of the state’s bureaucracy and thus bringing the issues into the open at a high level.” Roosevelt, like Stalin, was a political administrator in the sense that his first concern was power—albeit for very different ends.

How deliberate a policy was this on Roosevelt’s part? While he never formalized his highly personal methods of political administration and indeed ignored all abstract formulations of administrative problems, he probably was well aware of the justification of his methods in terms of his need to keep control of his establishment. Certainly he did not embrace unorthodox managerial techniques out of ignorance of orthodox ones. His navy and gubernatorial experience had given him a close understanding of basic management problems. His recommendations to Congress for administrative reorganization were right out of the copybook, as was his request, never granted, for the right of item veto over appropriations. Many of his subordinates came to respect his methods even while they were disconcerted by them. Harold Smith, who became budget director in 1939, found the President an erratic administrator. But years later, as the size and shape of Roosevelt’s job fell into better perspective. Smith told Robert Sherwood that Roosevelt may have been one of history’s greatest administrative geniuses. “He was a real artist in government,” Smith concluded.

Yet a final estimate of Roosevelt’s administrative role must also include the enormous amount of wasted energy, delays, and above all the attrition of Roosevelt’s programs—especially the recovery program—caused by his methods. Good direction not only stimulates the ideas and energies of men; it also brings them into constructive harmony. What then can be said about Roosevelt’s toleration of incessant tension and friction among his lieutenants? Certainly the main effect of this intramural sharpshooting was more destructive than constructive. Certainly Ickes’ neurotic fight to wrest Forestry from Wallace during the reorganization battle was an example of wasted energies with no gain. That the New Deal often faltered in execution the President himself recognized. If, as has been said, the only genuine test of efficiency is survival, the Roosevelt recession, the continuing unemployment of 1939, and the bleeding of the President’s recovery proposals in 1939 raise a serious question about the administrative adequacy of his direction.

Inevitably Roosevelt’s practices produced hurt and bewilderment among his subordinates. “You are a wonderful person but you are one of the most difficult men to work with that I have ever known,” Ickes blurted out on one occasion.

“Because I get too hard at times?” Roosevelt asked.

“No, you never get too hard but you won’t talk frankly even with people who are loyal to you and of whose loyalty you are fully convinced. You keep your cards close up against your belly.…” If the President would confide in his advisers, Ickes went on, their advice would prevent him from making mistakes. Roosevelt took the criticism with good humor—but he did not change his methods.

On another occasion Democratic politicians were pressing Roosevelt to appoint a member of the Democratic National Committee as a federal judge, while the Justice Department was backing a government attorney. The pushing and hauling had reached a pitch when the President summoned representatives of both sides to the White House. They stated their cases.

“I’ll tell you what I’m going to do,” Roosevelt said. “I’m not going to take either man.” He named his choice. “Have either of you ever heard of him?” Neither had.

“Well,” the President went on. “His father was a remarkable man. Once the old man was sitting on his yacht and a big wave swept him off. Then another big wave came along and swept him back on. A remarkable man!” And that was all the explanation his visitors ever got—but Roosevelt’s appointment turned out to be an excellent one.

As an artist in government Roosevelt worked with the materials at hand. The materials were not, of course, adequate. A final evaluation of Roosevelt as administrator must turn on his capacity to devise new materials out of which to fashion an administrative leadership that could stimulate men while keeping them in harness. In the end his capacity for effective administrative leadership turned on his capacity for creative political leadership.

The New Deal, wrote historian Walter Millis toward the end of 1938, “has been reduced to a movement with no program, with no effective political organization, with no vast popular party strength behind it, and with no candidate.” The passage of time has not invalidated this judgment. But it has sharpened the question: Why did the most gifted campaigner of his time receive and deserve this estimate only two years after the greatest election triumph in recent American history?

The answer lay partly in the kind of political tactics Roosevelt had used ever since the time he started campaigning for president. In 1931 and 1932, he had, like any ambitious politician, tried to win over Democratic leaders and groups that embraced a great variety of attitudes and interests. Since the Democratic party was deeply divided among its sectional and ideological splinter groups, Roosevelt began the presidential campaign of 1932 with a mixed and ill-assorted group backing. Hoover’s unpopularity with many elements in his own party brought various Republican and independent groups to Roosevelt’s support. Inevitably the mandate of 1932 was a highly uncertain one, except that the new President must do something—anything—to cope with the Depression.

Responding to the crisis, Roosevelt assumed in his magnificent way the role of leader of all the people. Playing down his party support he mediated among a host of conflicting interest groups, political leaders, and ideological proponents. During the crisis atmosphere of 1933 his broker leadership worked. He won enormous popularity, he put through his crisis program, he restored the morale of the whole nation. The congressional elections of 1934 were less a tribute to the Democratic party than a testament of the President’s wide support.

Then his ill-assorted following began to unravel at the edges. The right wing rebelled, labor erupted, Huey Long and others stepped up their harrying attacks. As a result of these political developments, the cancellation of part of the New Deal by the courts, and the need to put through the waiting reform bills, Roosevelt made a huge, sudden, and unplanned shift leftward. The shift put him in the role of leader of a great, though teeming and amorphous, coalition of center and liberal groups; it left him, in short, as party chief. From mid-1935 to about the end of 1938 Roosevelt deserted his role as broker among all groups and assumed the role of a party leader commanding his Grand Coalition of the center and left.

This role, too, the President played magnificently, most notably in the closing days of the 1936 campaign. During 1937 he spoke often of Jefferson and Jackson and of other great presidents who, he said, had served as great leaders of popular majorities. During 1938 he tried to perfect the Democratic party as an instrument of a popular majority. But in the end the effort failed—in the court fight, the defeat of effective recovery measures, and the party purge.

That failure had many causes. The American constitutional system had been devised to prevent easy capture of the government by popular majorities. The recovery of the mid-1930’s not only made the whole country more confident of itself and less dependent on the leader in the White House, but it strengthened and emboldened a host of interest groups and leaders, who soon were pushing beyond the limits of New Deal policy and of Roosevelt’s leadership. Too, the party system could not easily be reformed or modernized, and the anti-third-term custom led to expectations that Roosevelt was nearing the end of his political power. But the failure also stemmed from Roosevelt’s limitations as a political strategist.

The trouble was that Roosevelt had assumed his role as party or majority leader not as part of a deliberate, planned political strategy but in response to a conjunction of immediate developments. As majority leader he relied on his personal popularity, on his charisma or warm emotional appeal. He did not try to build up a solid, organized mass base for the extended New Deal that he projected in the inaugural speech of 1937. Lacking such a mass base, he could not establish a rank-and-file majority group in Congress to push through his program. Hence the court fight ended as a congressional fight in which the President had too few reserve forces to throw into the battle.

Roosevelt as party leader, in short, never made the strategic commitment that would allow a carefully considered, thorough, and long-term attempt at party reorganization. The purge marked the bankruptcy of his party leadership. For five years the President had made a fetish of his refusal to interfere in “local” elections. When candidates—many of them stalwart New Dealers—had turned desperately to the White House for support, McIntyre or Early had flung at them the “unbreakable” rule that “the President takes no part in local elections.” When the administration’s good friend Key Pittman had faced a coalition of Republicans and McCarran Democrats in 1934, all Roosevelt could say was “I wish to goodness I could speak out loud in meeting and tell Nevada that I am one thousand per cent for you!” but an “imposed silence in things like primaries is one of the many penalties of my job.” When cabinet members had asked during the 1934 elections if they could make campaign speeches, Roosevelt had said, No, except in their own states.

After all this delicacy Roosevelt in 1938 completely reversed himself and threw every ounce of the administration’s political weight—money, propaganda, newspaper influence, federal jobholders as well as his own name—into local campaigns in an effort to purge his foes. He mainly failed, and his failure was due in large part to his earlier policy. After five years of being ignored by the White House, local candidates and party groups were not amenable to presidential control. Why should they be? The White House had done little enough for them.

The execution of the purge in itself was typical of Roosevelt’s improvising methods. Although the problem of party defections had been evident for months and the idea of a purge had been taking shape in the winter of 1938, most of the administration’s efforts were marked by hurried, inadequate, and amateurish maneuvers at the last minute. In some states the White House interfered enough to antagonize the opponent within the party but not enough to insure his defeat. Roosevelt’s own tactics were marked by a strange combination of rashness and irresolution, of blunt face-to-face encounters and wily, back-scene stratagems.

But Roosevelt’s main failure as party leader lay not in the purge. It involved the condition of the Democratic party in state after state six years after he took over as national Democratic chief. Pennsylvania, for example, was the scene of such noisy brawling among labor, New Dealers, and old-line Democrats that Roosevelt himself compared it to Dante’s Inferno. A bitter feud wracked the Democracy in Illinois. The Democrats in Wisconsin, Nebraska, and Minnesota were still reeling under their ditchings by the White House in 1934 and 1936. The party in California was split among organization Democrats, $30 every Thursday backers, and a host of other factions.

In New York the condition of the Democratic party was even more significant, for Roosevelt had detailed knowledge of politics in his home state and had no inhibitions about intervening there. He intervened so adroitly and indirectly in the New York City mayoralty election of 1933 that politicians were arguing years later as to which Democratic faction he had aided, or whether he was intent mainly on electing La Guardia. In 1936 he encouraged the formation of the Labor party in New York State to help his own re-election, and he pooh-poohed the arguments of Farley, Flynn, and other Democrats that the Labor party would some day turn against the state Democracy—as indeed it later did. By 1938 the Democratic party in New York State was weaker and more faction-ridden than it had been for many years.

It was characteristic of Roosevelt to interpret the 1938 election setbacks largely in terms of the weaknesses of local Democratic candidates and leaders. Actually the trouble lay much deeper. The President’s failure to build a stronger party system at the grass roots, more directly responsive to national direction and more closely oriented around New Deal programs and issues, left a political vacuum that was rapidly filled by power groupings centered on state and local leaders holding office or contending for office. Roosevelt and his New Deal had vastly strengthened local party groups in the same way they had organized interest groups. And just as, nationally, the New Deal jolted interest groups out of their lethargy and mobilized them into political power groups that threatened to disrupt the Roosevelt coalition, so the New Deal stimulated local party groups to throw off the White House apron strings.

“If our beloved leader,” wrote William Allen White to Farley early in the second term, “cannot find the least common multiple between John Lewis and Carter Glass he will have to take a maul and crack the monolith, forget that he had a party and build his policy with the pieces which fall under his hammer.” The perceptive old Kansan’s comment was typical of the hopes of many liberals of the day. The President had pulled so many rabbits out of his hat. Could he not produce just one more?

The purge indicated that he could not. The hat was empty. But White’s suggestion posed the cardinal test of Roosevelt as party leader. How much leeway did the President have? Was it ever possible for him to build a stronger party? Or did the nature of the American party system, and especially the Democratic party, preclude the basic changes that would have been necessary to carry through the broader New Deal that the President proclaimed in his second-term inaugural?

On the face of it the forces of inertia were impressive. The American party system does not lend itself easily to change. In its major respects the national party is a holding company for complex and interlacing clusters of local groups revolving around men holding or contending for innumerable state and local offices—governors, sheriffs, state legislators, mayors, district attorneys, United States senators, county commissioners, city councilmen, and so on, all strung loosely together by party tradition, presidential leadership, and, to some extent, common ideas. As long as the American constitutional system creates electoral prizes to hold and contend for in the states and localities, the party is likely to remain undisciplined and decentralized.

Long immersed in the local undergrowth of American politics, Roosevelt was wholly familiar with the obstacles to party change. His refusal to break with some of the more unsavory local bosses like Hague and Kelly is clear evidence that he had no disposition to undertake the most obvious kind of reform. Perhaps, though, the President underestimated the possibility of party invigoration from the top.

Some New Dealers, worried by the decay of the Democratic party as a bulwark for progressive government, wanted to build up “presidential” factions pledged to the New Deal, factions that could lift the party out of the ruck of local bickering and orient it toward its national program. Attempts to build such presidential factions were abortive. They might have succeeded, however, had the President given them direction and backing. The New Deal had stimulated vigorous new elements in the party that put programs before local patronage, that were chiefly concerned with national policies of reform and recovery. By joining hands with these elements, by exploiting his own popularity and his control over the national party machinery, the President could have challenged anti-New Deal factions and tried to convert neutralists into backers of the New Deal.

Whether such an attempt would have succeeded cannot be answered because the attempt was never made. Paradoxically enough, however, the purge itself indicates that a long-run, well-organized effort might have worked in many states. For the purge did succeed under two conditions—in a Northern urban area, where there was some planning rather than total improvisation, and in those Southern states where the White House was helping a well-entrenched incumbent rather than trying to oust a well-entrenched opponent. The first was the case of O’Connor, the second the cases of Pepper and of Barkley. Indeed, the results of the purge charted a rough line between the area within the presidential reach and the area beyond it. Undoubtedly the former area would have been much bigger had Roosevelt systematically nourished New Deal strength within the party during his first term.

But he did not. The reasons that the President ignored the potentialities of the great political organization he headed were manifold. He was something of a prisoner of the great concessions he had made to gain the 1932 nomination, including the admission of Garner and other conservatives to the inner circle. His first-term successes had made his method of personal leadership look workable; overcoming crisis after crisis through his limitless resourcefulness and magnetism, Roosevelt did not bother to organize the party for the long run. As a politician eager to win, Roosevelt was concerned with his own political and electoral standing at whatever expense to the party. It was much easier to exploit his own political skill than try to improve the rickety, sprawling party organization.

The main reason, however, for Roosevelt’s failure to build up the party lay in his unwillingness to commit himself to the full implications of party leadership, in his eternal desire to keep open alternative tactical lines of action, including a line of retreat. The personal traits that made Roosevelt a brilliant tactician—his dexterity, his command of a variety of roles, his skill in attack and defense, above all his personal magnetism and charisma—were not the best traits for hard, long-range purposeful building of a strong popular movement behind a coherent political program. The latter would have demanded a continuing intellectual and political commitment to a set strategy—and this kind of commitment Roosevelt would not make.

He never forgot the great lesson of Woodrow Wilson, who got too far ahead of his followers. Perhaps, though, he never appreciated enough Wilson’s injunction that “if the President leads the way, his party can hardly resist him.” If Roosevelt had led and organized the party toward well-drawn goals, if he had aroused and tied into the party the masses of farmers and workers and reliefers and white-collar workers and minority religious and racial groups, if he had met the massed power of group interests with an organized movement of his own, the story of the New Deal on the domestic front during the second term might have been quite different.

Thus Roosevelt can be described as a great party leader only if the term is rigidly defined. On the one hand he tied the party, loosely perhaps, to a program; he brought it glorious victories; he helped point it in new ideological directions. On the other hand, he subordinated the party to his own political needs; he failed to exploit its full possibilities as a source of liberal thought and action; and he left the party, at least at its base, little stronger than when he became its leader.

Yet in an assessment of his party leadership there is a final argument in Roosevelt’s defense. Even while the New Deal was running out domestically, new problems and new forces were coming into national and world focus. Whatever the weaknesses of his shiftiness and improvising, these same qualities gave him a flexibility of maneuver to meet new conditions. That flexibility was desperately needed as 1938 and 1939 brought crisis after crisis in world affairs.