THE TOUR DIVIDE was something else, and if I could get that feeling again, from another experience, I wanted to. After I got back in June 2016, it didn’t take long to come up with an idea of riding to Magadan, a port town on the Sea of Okhotsk in the far east of Russia, but I don’t know when I’m going to do it. Especially not now since Dot arrived in October 2017 (but more about her later). It’ll take six weeks, if everything goes smoothly – 200 miles a day for six weeks, with loads of river crossings, where I could be stuck for ages waiting for a truck to hitch a lift over the water if I couldn’t cross it without being swept away. Part of me thinks I’ve got so much to learn before attempting it, while the other part thinks, Bugger it, I’ll just set off and cross the bridges, or rivers, as I come to them.

So, with Magadan too much to take on with everything else that was happening at the time, the TV lot came up with a load of rare pushbike challenges, and one of them was riding around the coast of Britain. I looked at the record, set in 1984 by Nick Sanders, who is better known as a motorcycle distance record holder. He set it at 22 days and I looked at it, did a few quick sums in my head and told the TV bods I reckoned I could ride around the coast of Britain in 20 days. I added that I’d set off the first week in December, so I’d finish the ride on Christmas Day. That side of things was my idea.

As part of the filming I met up with Nick Sanders. He’s definitely a doer. He’s made a job out of breaking long-distance records, mainly on motorbikes, but he was a professional cyclist years ago, I think. He has a very weathered appearance. The time he set was very impressive.

I came back from the Tour Divide and worked like hell on the trucks, then went to China to film the Our Guy in China programmes. As part of that I did a ride through the Taklamakan Desert. It wasn’t far, 347 miles, non-stop. I did 300 miles in 24 hours, only stopping to eat and run behind a sand dune for a leak every now and then. I’d done enough 24-hour Strathpuffer bike races that I know what it’s like to cycle for 24 hours and how much effort I can put in at the beginning and still be going at the end. Plus, because this was not far off the back of the Tour Divide, it didn’t feel like much of a challenge. I had all the TV crew and all the health and safety folks that TV demands. They didn’t need to do anything, but insurance policies and risk assessment forms say they’ve got to be there just in case, so that’s the way it is. I didn’t need them for the Tour Divide, but I know the TV lot have to dot the i’s and cross the t’s. I did get a monk on when they were driving right in front of me filming and chucking up sand and blowing diesel fumes in my face. The previous record for this desert crossing was 47 hours and I did it in 28 hours and 17 minutes, an average of near enough 12mph.

When I got back from China I was back at Mick Moody’s truck yard in Grimsby, playing catch-up, doing a few jobs on Scanias he’d taken in on part-exchange and getting stuff ready for MOTs, and doing other bits because it wasn’t long before I had to fly out to New Zealand for a week at the Burt Munro Challenge in his home town of Invercargill.

Burt Munro is the man whose story of record-breaking at Bonneville Salt Flats, in Utah, on his home-built special, was made into the 2005 film The World’s Fastest Indian. The Burt Munro Challenge was a week of motorbike races, of all types, to celebrate this legend, who died in 1978.

I was only interested if I could take part on my own bike, so my Martek was shipped out. It’s the turbo Suzuki special that I’ve owned for years and raced at the 2014 Pikes Peak International Hill Climb in Colorado. Me and Shazza followed it out to New Zealand, and had a great time. I’d been a few times before, for the Wanganui Road Races that take place on Boxing Day on the Cemetery Circuit, and I love the country. The people are great and it’s so laid back. It’s a bit backward, there’s loads of open space, no one seems to be in a rush.

We had a couple of days without bikes. One day I went out with a group for a 40- or 50-mile mountain bike ride and Sharon arranged to meet up on the ride and for us to do a bungee jump together, at the 43-metre AJ Hackett Kawarau Bridge Bungy, the world’s first permanent bungee site. Neither of us had done one before and I thought she might select reverse when she saw it but she didn’t and it was mega to do it together.

The rest of the time I was in a shed working on the Martek. It was nothing but trouble, but I liked mucking about with it. I did a couple of track days, at Teretonga racetrack, a ten-minute drive from Invercargill. I borrowed a van, paid $40 and I had the track nearly to myself. What a life. I’d be having all this grief with the bike, not sure why it wasn’t running right, then I’d find myself on track with a new Fireblade or a BMW S1000R and I’d smoke them on this thing concocted in my shed, and it was the best feeling in the world. Then something would go wrong again, but it was all worth it for those moments.

When I was in New Zealand I caught a right stonking cold, the last thing I needed, on top of a 28-hour journey home, before starting something like the ride I had planned. I was back for three or four days, working at Moody’s, before the start of the round Britain ride. Oh, and the pub I’d bought was opening the night before I set off. Like I said, busy.

John, from Louth Cycles, built me another bike, a new version of what I’d done the Tour Divide on. This time it was a Salsa Cutthroat, not the Salsa Fargo I’d ridden through North America on. Salsa is a California-based company and they describe the Cutthroat as a ‘Tour Divide-inspired, dropbar mountain bike’. It sounded perfect and looked trick, kitted out with Hope parts, all made in England. It was a step up from the Fargo.

I was bunged up with snot and cold, and the last thing I should’ve been doing was getting on a pushbike before the big ride, but I hadn’t ridden this new bike at all so I set off to work and back, on a cold December morning, just to make sure everything was all right. It was, so I didn’t sit on a pushbike again until I set off three days later. I just worked on the trucks, blew my nose and slept.

The idea was to start in Grimsby, and ride the whole circumference of Britain in 20 days. When I’d helped come up with the idea I thought I could piss it.

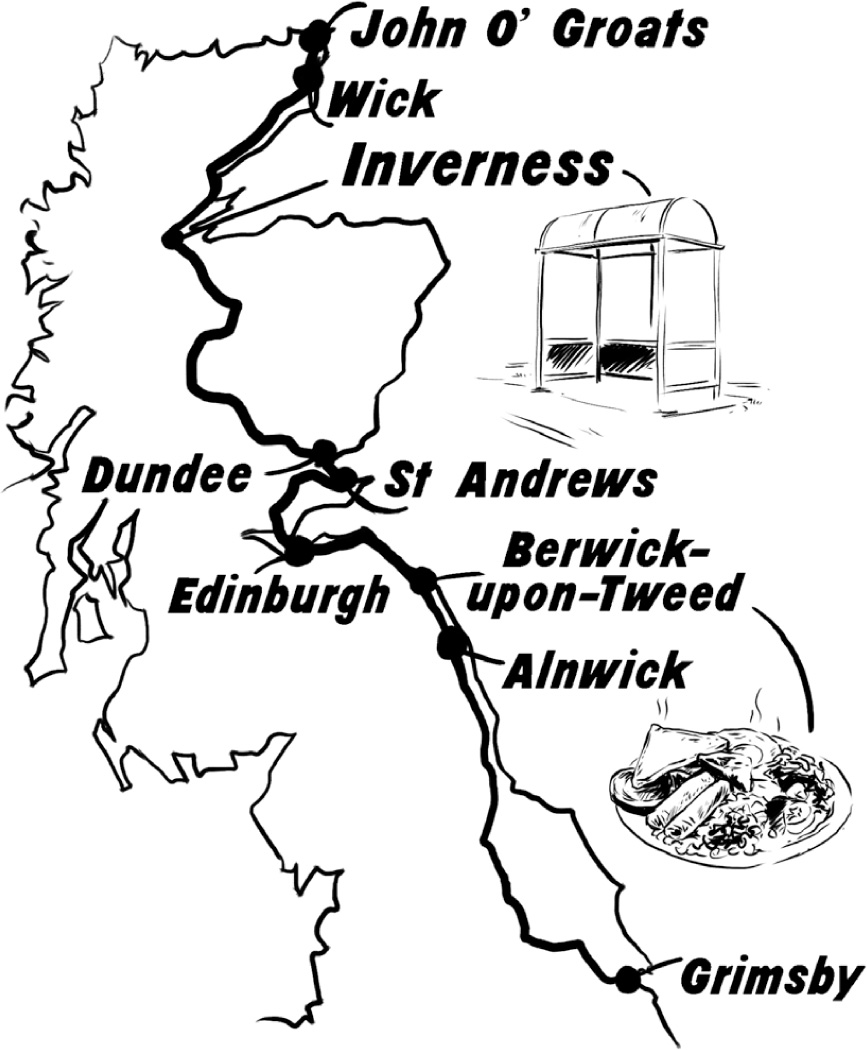

The TV lot had got Garmin involved and they’d made a full route plan, coming up with one of 4,866.6 miles. The current record was 4,838 miles, set in 1984. New one-way roads along stretches of coast must have made the difference. Garmin also worked out there was 69,443 metres of climbing, the equivalent of riding the height of Everest nearly eight times in 20 days. Everyone had put loads of effort in, to make sure it all went smoothly. The only fly in the ointment was me.

Even though the Garmin route was clockwise, heading south from the Grimsby start point, I’d decided I would head north, because there was a good chance I’d get a tail wind up the north-east coast of England and the east coast of Scotland.

The pub opening was great, and I slept in Kirmo at my sister’s, Sal, on the Saturday and got up at three in the morning to get to the start in Grimsby. I wanted to be in Scarborough for nine that morning.

Two of my mates, Dobby, whose house I rented in Caistor when I moved out of Kirmington, and John, a potato merchant and a keen cyclist, rode with me on the first day. The route was all on road. I was doing a bit of work, but for most of it I was in the slipstream of those two boys, taking it a bit easy.

The weather was cold but mint on that first day. I was probably 100 miles into the ride and thought, Something isn’t right here. But I kept quiet. I just thought I had to man up.

Dobby and John ran out of steam after about 150 miles, near Newcastle, got picked up and given a lift home. I got to Alnwick, and I was on schedule. Shazza was following in the Transit, doing the support truck side of things. So I kipped in the van. Everything was still on schedule at the end of the first day, but my Achilles was giving me bother.

I slept for four or five hours, woke up at four in the morning, got on my bike and, after struggling to find anywhere else to eat, headed to Berwick-upon-Tweed for breakfast. I had a massive fry-up in there, with Shazza and the TV lot. I realised I wasn’t 100 per cent, but thought I’d be all right. I didn’t like being the centre of everyone’s attention, though. I’m used to having the camera pointed at me when I’m doing the TV job, I’ve been doing it enough year’s now, but for some reason I hadn’t even considered it was going to be like that on this record ride. The TV lot weren’t holding me up, and, as usual, they couldn’t do enough for me, but it was another area of my life that TV had come into. Pushbiking had always been just for me, the escape from everything. Now it wasn’t.

I set off again, up to Edinburgh, then over the Forth Road Bridge. I was seeing the film crew during the day, and I knew they were only doing their job, and it was all part of it, but I kept thinking, Bugger off! They’d be following me, or right in front of me. And that’s what made me realise that the loneliness was one of the reasons I loved the Tour Divide so much.

I carried on towards Dundee, and I didn’t quite make the overnight stop that was on the plan. I realised if I was behind schedule by the end of day two I was going to struggle. I wasn’t on song. Really, I was fucked. Because of that, and because there was always someone around that I knew, I was stopping for too long. I couldn’t just get my head down.

I knew I was on the back foot before I even set off, but I wasn’t selecting reverse at that point. Everything was in place. Too many people were relying on me.

A couple of days into the ride it had dawned on me that this wasn’t just a case of needing to man up. The problem was I’d half finished myself at the Tour Divide, without knowing or admitting it. I thought I was the strongest I’d ever been, but I’d pushed myself preparing for the Tour Divide, doing the ride itself, and I hadn’t given myself time to recover. I’d done that ride in 18 days, when the guidebook I was referring to was recommending over 70 days to do it in. Then I’d been flat out since I got home.

Another big thing was the bike. I’d been so used to pedalling my single-speed, the Rourke-framed bike I ride to work and back on, or my Tour Divide bike, but I got on this new bike and it was different. The main thing being that the cranks and pedals were slightly wider apart than I was used to and my legs just didn’t like it.

I had another few hours’ kip in the van, then set off again to St Andrews. On a ride like this you have to grit your teeth for the first five miles, while everything remembers what it is supposed to be doing, and, if you’re fit, that’s it: you’re into it for the rest of the day. Because you’re covering big distances, day after day, you never feel on top of the world, but before you know it you’ve done 50 miles. Slogging up through Scotland was different, because I couldn’t escape the unforgiving pain. As I tried to compensate for the pain in my Achilles, I’d adjust my riding position and that put my knees out, which put my hips out, which put my lower back out.

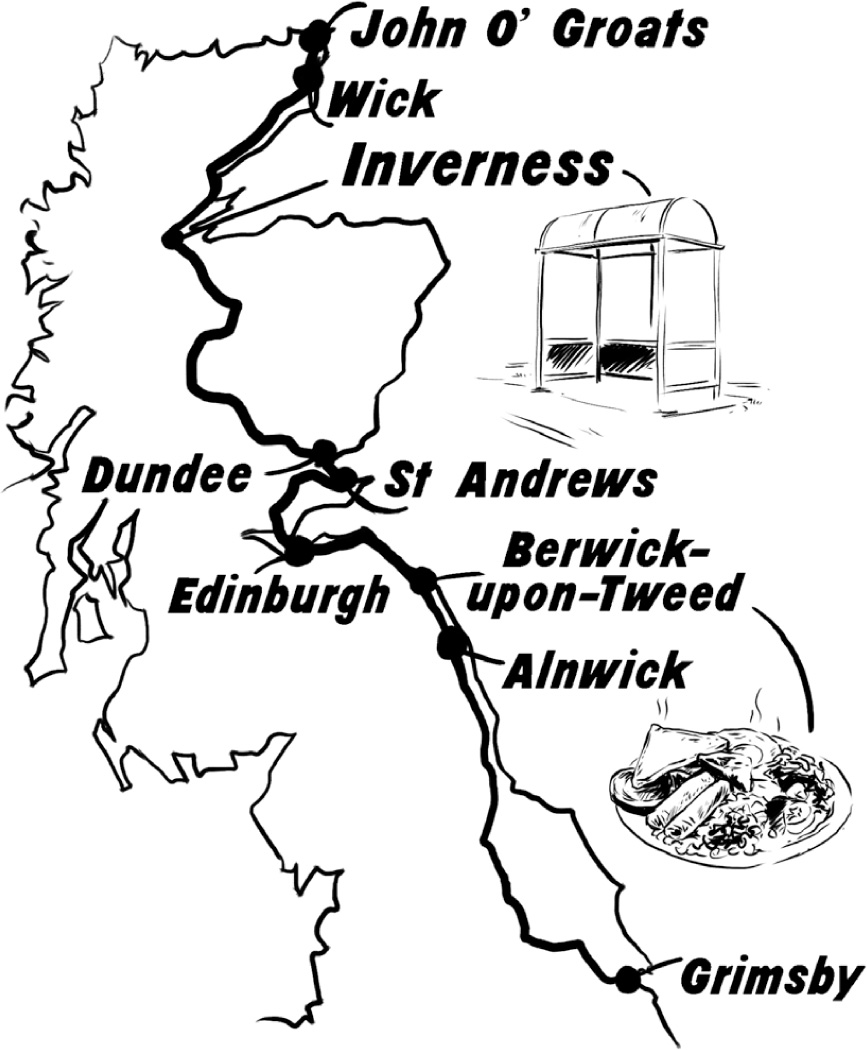

At Inverness I had to stop in a bus shelter and have half an hour to myself. I’d only covered 20 miles. I wasn’t right.

The weather was wet and cold, but I was dressed for it, so I wasn’t feeling it. Northwave thermal winter boots, leggings over Lycra and waterproof trousers over the top, and a raincoat. The lack of daylight was a problem I hadn’t thought about. But cycling in the dark for so many hours a day changes how you feel.

That night I stayed just below Wick, right in the very north of Scotland. I’d done a big chunk of riding, and I hadn’t been hanging around, but that was it. The TV lot knew something wasn’t right. I got up and realised, This isn’t happening. The film crew had swapped back and forwards a few times. I got to John O’ Groats by one in the afternoon and hated admitting I couldn’t do it, but I had to tell them, This isn’t happening, boys.

After what I’d put my body through that year, it was just a challenge too far. I keep saying I want to try to break myself; well, I’d just about succeeded. I was gutted I’d let myself down. I thought I had enough of a stubborn head and mental strength to get over some sore legs, but the strain on my Achilles and the repetition of tens of thousands of pedal rotations was too much. It wasn’t the worst pain I’ve ever felt, not like slipping in the shower with a broken back or hospital porters using my broken leg to open some heavy swing doors in a Manx hospital, but it was relentless. The only time it didn’t hurt was when I reached a big hill and I stood up pedalling, pushing into it.

No one at the TV company was trying to talk me into keeping going. Shazza, the one who was getting me out of bed and onto the bike at four in the morning, the one encouraging me to keep going, could tell I couldn’t go on.

A lot of time and money had gone into it and there wasn’t a single thing to salvage. From the TV point of view I either did it or I didn’t. And I didn’t. Dead simple. Plenty of the stuff we do for telly is ambitious and it doesn’t always go according to plan, but we’ve always managed to get something out of it to make a programme, even when it was that pedal-powered boat thing that was a total failure. Not this time, though. I let everyone down.

There was plenty I know now I could’ve done differently. I should’ve had more time off. I should have had more time getting used to the new bike or just used a proven bike, that I’d done loads of miles on. I do think if I’d set off on one of my bikes, that I was used to riding, I might have been able to do it, but ifs and buts are pots and pans, and if my auntie had balls she’d be my uncle …

And I wouldn’t do it in winter. On top of all those other excuses, the snotty cold, working like mad, New Zealand, China, Tour Divide … the other part was all the darkness. In Scotland I wasn’t having much more than eight hours of murky daylight, and cycling in pitch black affects you. You’re just not seeing anything. I thought I’d be all right, because I’d cycled up to the Strathpuffer, the far north of Scotland, in winter, and then competed in the 24-hour race, but this was different.

On the Tour Divide I could have sat down and cried my eyes out and it wouldn’t have made a single bit of difference, because I was on my own. It was all on me. Shouting and screaming was just wasting energy. I just had to keep moving forward, even at 1mph; it didn’t matter, I was one step closer to the finish. That was the mindset I got into in America and I couldn’t get into the same mindset on the ride around Britain, because there was too much support. As good as it was, that’s not why I do things like this.

With everyone heading home, me and Shazza had one night in a B&B in Inverness before driving back to Lincolnshire and I was in a bad mood, not talking, miserable, brooding. We got home late on Saturday, I was back to work on Monday … I gave the pushbike a miss for a while. I could still feel the pain in my heel. I wasn’t about to start running, but I could get on with stuff in the yard. Then work till Christmas. There was no point in resting now.