Visualizing a Partial Revolution

HOW A REVOLUTION UNFOLDS and how it is visualized are often at odds with each other. Consider the King Street Massacre, better known as the Boston Massacre—a pinnacle moment in history that laid the foundation for the American Revolution.

On March 5, 1770, a multiracial mob confronted a small group of British soldiers and turned a tense situation into a crisis. Massachusetts was the epicenter of the growing revolt against British policy, and the presence of British soldiers in Boston was viewed as an occupying army sent by the Crown and Parliament to enforce its will on the colonial population.

Things began to escalate on March 2, when a group of Boston rope makers insulted a British soldier, knocked him down, and took his sword as a memento. The soldier retreated to his barracks and returned with reinforcements, but again the rope makers prevailed. The following day British soldiers from the 14th and 29th Regiments exacted revenge by beating anyone they could find who was out walking on the streets. Random skirmishes continued the following day.

On March 5, daytime fights turned into a nighttime riot on King Street. A multiracial mob of seventy people or more, armed with sticks and clubs, pelted a group of seven soldiers with snowballs. As tensions grew, the size of the crowd grew. Sailors rushed up from the docks and joined rope makers, journeymen, apprentices, and others to form a sizable crowd of upward of one thousand. The crowd berated the soldiers with insults, attempted to knock their guns out of their hands, and dared them to fire. Soldier Hugh Montgomery was the first to oblige. Montgomery fired as he was struck and falling to the ground. Other soldiers followed suit.

Four people in the crowd were instantly killed. One would later die of his wounds. Those killed were a sailor, a second mate on a ship, a ropewalk worker, an apprentice to a leather-breeches maker, and an apprentice to an ivory turner.1 The first person to die was Crispus Attucks, a six-foot-two sailor and former slave who was part African American and part Native Indian. Attucks would have the unlucky distinction of becoming the first martyr of the American Revolution. He would also become emblematic of the power dynamics at play as the revolution unfolded: a revolution instigated by working-class people (both urban and rural), and a revolution where power-would ultimately be seized by the colonial elites who fought on two fronts: one against British rule and one against their own working class.

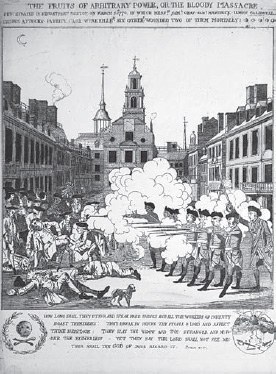

The Bloody Massacre

Images of the Boston Massacre represented this power play. Silversmith, engraver, and patriot Paul Revere published the most influential Boston Massacre image on March 26, three weeks after the riot. His image The Bloody Massacre was riddled with factual errors.

Revere’s engraving depicted the British soldiers all firing at once, instead of randomly. Capt. Thomas Preston was depicted as giving the command to fire, instead of simply being present among the soldiers. Revere added a fictitious gun shooting down from the second-floor window of the Custom House that he renamed “Butcher’s Hall.” He also depicted the crowd as small: two dozen people instead of upward of one thousand. More problematic, Revere depicted the crowd as passive—without sticks and clubs—turning a working-class mob into a respectable assortment of men and women. Worst of all, he depicts Attucks as someone he wasn’t: a white man.

Revere’s engraving was designed as anti-British propaganda that fell in line with how wealthy colonial elites wished to portray the revolution: a revolt that was led by an educated, white, male leadership that had rallied the colonial population against the unjust policies of the British Parliament and its use of force. This was far from reality, but artistic representations of significant historical events are rarely accurate. Instead they express points of view and political agendas. They are a form of media and part of the fight to win over public opinion.

Revere’s unstated objective with his print was to direct colonial anger toward the British and to defuse class tensions among the colonial population. His source image derived from the Boston artist Henry Pelham. Pelham had witnessed the massacre and lent Revere a copy of his engraving for reasons that remain unclear. Revere himself was not a printmaker or “artist,” per se. He was an engraver who copied other people’s images, primarily images by British artists. This time he copied Pelham’s work.2

However, Pelham never expected Revere to duplicate his image, much less publish it before he had the chance to do the same. But to Pelham’s dismay, Revere copied his image, almost to the last detail, while adding his own text, and then advertised the print for sale on March 26, one week before Pelham released his own print for sale on April 2.

Pelham was furious at Revere for stealing his image. He wrote Revere a scathing letter, stating that Revere had plundered him “on the highway” and he was guilty of “one of the most dishonorable Actions you could well be guilty of.” But the real issue in terms of its national impact was not the plagiarism, but the influence that the Revere print’s message exerted on the colonial population.3

Revere’s engraving came to serve as the primary image that documented the Boston Massacre. Copies of his prints (he pulled two hundred impressions) traveled up and down the eastern seaboard and across the Atlantic, where they were subsequently copied (without permission) by other artists and republished in broadsides, newspapers, and other forms of print media. Thus, his image served as news—visual information that augmented the text about the massacre—all of which incited anger against the British Parliament while downplaying the role that the multiracial mob had played in the action.

Paul Revere, after Henry Pelham’s design, The Bloody Massacre Perpetrated in King Street Boston on March 5th 1770 by a Party of the 29th Regt., 1770 (LC-DIG-ppmsca-01657, Library of Congress)

This newsmaking role is significant, for in the 1770s a mass media did not exist. News traveled slowly and was transported by ship or by horseback down poorly constructed roads. At best, it took three weeks for news to travel by road from Boston to Savannah, Georgia. Often it would take six. Traveling lines of communication to frontier communities took much longer, if at all.4 When copies of Revere’s engraving and subsequent broadsides reached far-flung communities, it was likely the first and only image that people would see that visualized the massacre.5

Henry Pelham, The Fruits of Arbitrary Power, Or the Bloody Massacre, 1770 (American Antiquarian Society)

This singular version of events was also disseminated overseas. Boston Whigs sent copies to London, hoping that the brutal image and text would find a sympathetic audience among the British public, which would then lead to a public outcry against the policies and actions of the British government toward the colonial population. Once again, the Revere/Pelham image (which was reengraved and circulated around England) obscured the class tensions that existed in colonial America, including the reality that some workers and tenants had sided with the British, placing more trust in the British Parliament than the colonial elite.

Revere’s omission of the multiracial mob was intentional. The Pelham image served as his source material, but he inserted additional information as he saw fit, and he hired the artist Christian Remick to hand color his print edition. Revere could have easily instructed Remick to color Attucks and others in the crowd black, but he chose not to. He could have easily added sticks and clubs to the hands of those in the crowd, but instead, he made the crowd white men from the respectable artisan class. Marcus Rediker writes that Revere “apparently did not want the American cause to be represented by a huge, half–Native American, half–African American, stave-wielding, street-fighting sailor . . . Attucks was the wrong color, the wrong ethnicity, and the wrong occupation to be included in the national story.”6

This omission in Revere’s image echoed the dominant narrative of the American Revolution and the formative years of the new nation, a narrative that was written by the colonial elite. The same elite that attached themselves to the popular uprising in colonial America—whose foot soldiers were debt-ridden farmers, sailors, and disenfranchised artisans and laborers—yet once the British were defeated and American independence was won, the colonial elite kept similar oppressive structures in place.

Women remained second-class citizens: unable to vote, unable to hold political office, receive a higher education, unable to work in the majority of occupations. Africans remained enslaved. Eastern Native people were forced to relocate to the western plains as their land was taken from them. As for the white, male working class, it was welcomed in the new nation, but the vast majority of colonial people remained impoverished. Those without property were disenfranchised. They were not allowed to vote, and neither were they allowed to participate in town meetings. Instead, they found themselves positioned against a new power—the ruling elite, the laws of the courts that favored wealth, and a federal government that had the tools to quickly put down future uprisings should they begin.

Revere’s Ride Away from the Mob

In the mid-eighteenth century, Boston was a mob town in the best sense of the word. Sailors were often the first to lead the tumults. In 1747, sailors rioted against impressment—losing one’s freedom when the British would force sailors on the docks against their will to serve in the British Navy. At one point during a Boston riot, sailors lifted a British-owned boat from the harbor, carried it to the Commons, and burned it to the ground. Additionally, four separate grain riots and two market riots had taken place before 1750.7

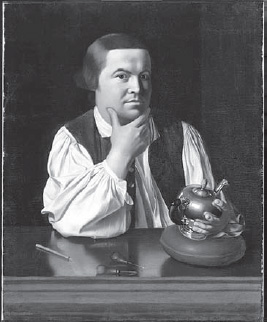

John Singleton Copley, Paul Revere, 1768 (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

In Boston, the dominant occupation was to be an artisan—an occupation that excluded women. Artisans started out as apprentices, became journeymen, and if fortunate, became mechanics and owned their own shops. In 1790, 1,271 artisans could be found in Boston out of 2,754 adult males.8 These urban workers, along with the farmers in the surrounding communities, were the backbone of the Revolution, but not the spokespeople of it. Rather, individuals such as Samuel Adams (born into an elite family and educated at Harvard) and John Hancock (one of the wealthiest merchants in New England) were. Ray Raphael writes, “The verbiage was clearly the work of educated Boston Whigs, not their country cousins who were actually driving the Revolution forward.”9 Consequently, these artisans and farmers were excluded from the policymaking. They were not invited to the Continental Congress in 1774 (an illegal body and forerunner of the new independent government), and neither were they invited to Philadelphia to draft the new Constitution.

![]()

A conundrum existed for Paul Revere. Revere identified himself as an artisan. He was a silversmith and engraver by trade, and admired by Boston’s working class. When Revere allowed John Singleton Copley to paint his portrait in 1768, he made certain that he was pictured as an artisan, surrounded by the tools of his trade.

But Revere was also connected to the elite leadership in Boston. He was a mechanic and belonged to the top echelon of the artisan community. Mechanics in colonial America faced competition from English manufacturers, and when Parliament began levying taxes and forcing oppressive regulations on the colonies, many sided against the British.

Revere became active when Parliament passed the Stamp Act in 1765—a tax on stamped paper that transferred the costs of the French and Indian War (the Seven Years’ War) onto the colonial population. He also became a member of pro-independence groups—the Loyal Nine, the Sons of Liberty, and the North End Caucus. Both the Loyal Nine and the Sons of Liberty drew from the middle and upper class, with members representing merchants, mechanics, distillers, and ship owners, among others.

Revere was not unlike the colonial elite leaders and merchants who feared that the power of the mob would extend to other facets of colonial and post-colonial life. The merchant El-bridge Gerry had warned Samuel Adams in 1775 that a new government had to be established quickly after British rule, for “the people are fully possessed of their dignity from the frequent delineation of their rights . . . They now feel rather too much of their own importance, and it requires great skill to produce such subordination as is necessary.”10 One place that the mechanisms for subordination existed was in the courts. Boston’s elite had urged John Adams and Josiah Quincy to defend the British soldiers responsible for the Boston Massacre, and during the proceedings both Adams and Quincy were highly antagonistic toward the multiracial mob. Adams labeled the crowd a “motley rabble of saucy boys, negroes and molattoes, Irish teagues, and out landish Jack Tarrs” and stated that the appearance of Attucks “would be enough to terrify any person.”11 Certainly the crowd of more than 10,000 colonists (out of a city population of around 15,000) who marched in the funeral procession for Attucks and the four others killed did not feel so negatively toward the mob. Yet the court of public opinion and the court of law were different bodies. Adams and Quincy were able to obtain a favorable decision for their clients. All of the soldiers were acquitted, except Montgomery and Kilroy, who were convicted of manslaughter, yet their punishment consisted of only being branded on the hand.

Ironically, John Adams himself would credit the mob for sparking the revolution. He later described the Boston Massacre as having laid the “foundation of American independence,” and when he penned a letter about liberty to Gov. Thomas Hutchinson in 1773, he signed it not with his own name, but with the name “Crispus Attucks.”12 This remarkable double consciousness signified that Adams and others in his class both depended upon and despised the multiracial mob. They needed the rural and urban working-class revolt to spark the revolution and to fill the front lines, yet they feared the power of the mob and did everything they could to contain it and crush it once they obtained positions of leadership and power.

Sites of Resistance and Class Conflict

Though missing from Revere’s famous engraving, examples of working-class resistance can be found in other items of material culture from the Revolutionary era—printed material, engravings, paintings, monuments, and mementos, to name just a few. However, the best example is a tree.

The Liberty Tree in Boston, located at the intersection of Essex and Newbury Streets (today Essex and Washington), was an epicenter of anti-British organizing. The Liberty Tree, first known as the Great Elm or the Great Tree, was dedicated on September 11, 1765, and stood as an important site of resistance for a decade until British troops cut it down in 1775.

For ten years the tree served as a location where Bostonians—or at least white men of all classes—could take part in civic life, regardless of whether they owned property.13 The Liberty Tree was a meeting space for assemblies, orations, street theatre, and mock trials, and often served as the starting point or stopping point for funeral processions for martyrs of the revolution.

The tree itself was also a canvas for creative resistance. Effigies and lantern slides (painted images on thin paper that were pasted over a framework and illuminated with a candle from within) hung from its branches. Events were posted on the trunk of the tree and a liberty pole ran up the center and extended above its tallest branch.

During the first year of the Liberty Tree, working-class artisans directed the bulk of the actions. They were led by the shoemaker Ebenezer Mackintosh, nicknamed the “Captain General of the Liberty Tree,” who had upward of three hundred men at his command. His notoriety ranged from leading peaceful parades against the Stamp Act to leading mob actions that completely dismantled Lt. Gov. Thomas Hutchinson’s mansion.14

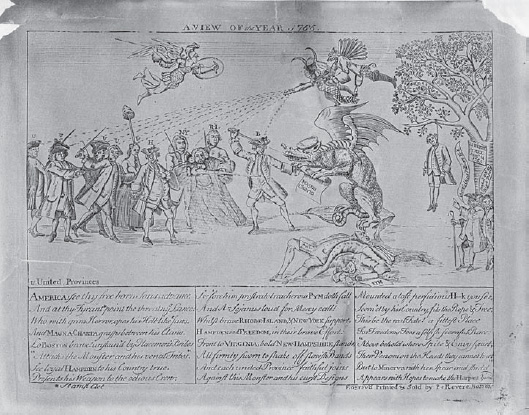

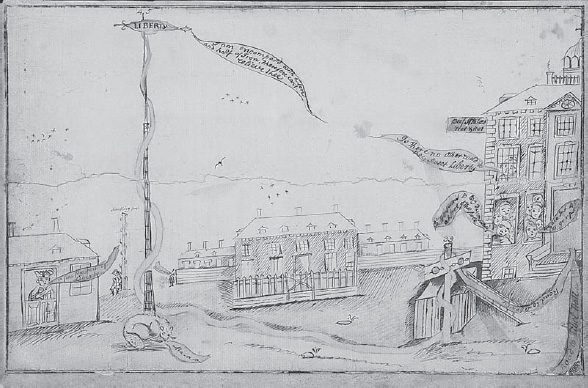

Paul Revere, A View of the Year 1765, 1765 (American Antiquarian Society)

Mackintosh caused a dilemma for the elite patriot leadership. The Sons of Liberty leaders could not ignore him, and neither could they reject him outright, due to his popularity. So they embraced him. They followed the strategy of Robert R. Livingston Jr., a wealthy landlord in the Hudson Valley in New York, who in response to a series of urban and rural uprisings warned that the wealthy should learn “the propriety of Swimming with the Stream which it is impossible to stem.”15 That the wealthy “should yield to the torrent if they hoped to direct its course.”16

The Sons of Liberty followed this path. They embraced Mackintosh, won the respect of the crowd, and then they began to slowly distance themselves from him.17 Their slogans included “No Mobs—No Confusions—No Tumults” and “No Violence or You Will Hurt the Cause.”18

This is why it is so perplexing that Paul Revere—a member of the Sons of Liberty—paid homage to the mob actions with his engraving A View of the Year 1765, a print that featured a depiction of the Liberty Tree. A View of the Year 1765 positioned Revere in solidarity with the working class (and the mob), and much like all of his images, it was directly copied from another artist. This time the source material was a British cartoon entitled “View of the Present Crisis” that was published in April of 1763 and critiqued the Excise Bill of 1763. Revere’s print had a different political agenda. It was a scathing piece of anti-British propaganda that was aimed at the Stamp Act and depicted colonists raising their swords to slay a dragon that represented the detested law. To make his point clear, Revere added text to the bottom, labeled the dragon and the figures, and erased three figures on the far right, replacing them with a scene from the Liberty Tree.19

Revere could have simply depicted the tree, considering that all classes claimed ownership to it, yet he chose to include symbols that celebrated the events of August 14, 1765, when a mob action forced Andrew Oliver, the colony’s stamp distributor, to resign from his position.20 The events of August 14 began when organizers set up next to the Liberty Tree and did a mock stamping of goods as farmers from the countryside passed by en route to the downtown markets. As the afternoon sun began to cast its shadow, thousands gathered in front of the tree. An effigy of Oliver was hung from it. At five o’clock a mock funeral assembled and paraded through town carrying Oliver’s effigy. Next, the mob went to Oliver’s office and leveled it with a battering ram. Not content, the mob then went to Oliver’s house and demanded his resignation. Oliver was nowhere to be found, so the mob dismantled his house, stamping each piece of timber before it was thrown in a bonfire. Not surprisingly, Oliver sent word the next day announcing his resignation.

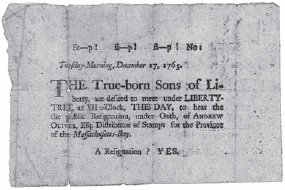

“Stop! Stop! No: Tuesday-Morning, December 17, 1765”: Loyal Nine, broadside announcing resignation of the Stamp Act Commissioner Andrew Oliver December 1765 (Massachusetts Historical Society)

However, Oliver’s nightmare did not end there. The Loyal Nine posted upward of 100 broadsides around Boston in the dead of night that announced that on December 17, Oliver would publicly resign in front of the Liberty Tree.21

True to the broadsides’ advertisement, Ebenezer Mackintosh and a company of men escorted Oliver to the site, where he was forced to resign in front of a crowd of approximately two thousand people.22

Here, public theatre merged with public humiliation, serving as a warning sign to others that they would meet the same fate if they backed the Stamp Act.23 These tactics showcased just how radical the movement was in 1765 when its leadership was in the hands of working-class people. More so, it exemplified just how important the Liberty Tree was as a site to gather, organize, and protest. The Liberty Tree allowed those who detested British rule to occupy space—a tactic that future movements would embrace, ranging from sit-down strikes in auto plants in the 1930s to campus occupations during the Vietnam War to the occupation of Zuccotti Park during Occupy Wall Street in 2011, among others. This tactic—occupying space—allows movements to recruit more people and forces the opposition to act. In short, it serves to escalate the conflict.

![]()

Boston’s Liberty Tree was not the only important location for organized resistance and occupying space. Another symbol of colonial revolt included liberty poles. These markers, much like the Liberty Tree, were also key locations for working-class people to congregate and to openly express their dissent toward British rule.

Liberty poles were found throughout the colony. However, the most famous liberty pole was located in New York City in “the fields” and close to the barracks of British soldiers. This pole, first erected in 1766, was eighty-six feet tall and further topped by another twenty-two-foot-tall pole.

Pierre Eugene du Simitiere, Raising the Liberty Pole in New York City, ca. 1770 (Library Company of Philadelphia)

The pole itself was crowned with the number “45” to link the imprisoned patriot Alexander MacDougall (put in jail for printing an inflammatory broadside) with the imprisoned English reformer John Wilkes, who was sympathetic to the cause of the American revolt. To the British Parliament and Crown, it must have stood as a 108-foot-tall monument against their rule—a provocative middle finger that was designed to escalate tensions. British forces cut down the pole four times before colonists resorted to fortifying it with iron hoops crafted by blacksmiths. In 1770, sailors and laborers fought British soldiers in hand-to-hand combat to defend the pole in a skirmish that led to the Battle of Golden Hill, a shift that historian Alfred F. Young describes as a celebratory space segueing to a “staging place for military action.”24 This materialized in 1776 during the Revolutionary War, when the pole was cut down by the British Army as they occupied the city.

Just like liberty poles and the Liberty Tree, King Street itself also became an important site for organizing and creative resistance. Following the Boston Massacre, the colonial government in Boston voted in 1770 that speeches would be held there annually on March 5, followed by various exhibitions on the street. During these celebrations, lantern slides adorned balconies overlooking the massacre site, while other lantern slides were carried in parades or hung at the Liberty Tree.25 Historian Philip Davidson writes that “the exhibition depicted the murder, the troops, and the slaughtered victims [and included the slogan] ‘The fatal effect of a standing Army, posted in a free City.’”26

The March 5 remembrances would not last long. Annual commemorations ended in 1783 when March 5 (the Boston Massacre) was rolled into the July 4th holiday. Erased was a celebratory day to working-class revolt and revolution, and in its place was a holiday that celebrated independence and patriotism. In short, the March 5 remembrance day met the same fate as the Liberty Tree and the poles: it was cut down.

A Need for More Liberty Poles

Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker describe the Revolutionary War era in three stages: “militant origins, radical momentum, and conservative political conclusion.”27 However, the success of the conservative elites did not defuse class tensions during the War of Independence (1775–1783) or after. If anything, the tensions heightened.

During the war, the wealthy could opt out of the draft by paying for someone to serve in their place, leaving the bulk of the fighting to the poor. To add insult to injury, many soldiers were not given the pay that was promised to them, and pensions for military service were not forthcoming for decades.

All the while, the working class were being shut out of the conversations that established the legal framework for a new nation. The 1787 Philadelphia Convention that drafted the Constitution was a closed meeting dominated by wealthy conservatives. William Manning, a New England farmer, soldier, and author, compared the Constitution to a fiddle: a document that was “made like a Fiddle, with but few Strings, but so the ruling Majority could play any tune upon it they please.”28 He added that it was “a good one prinsapaly [sic], but I have no doubt but that the Convention who made it intended to destroy our free governments by it, or they neaver [sic] would have spent 4 Months in making such an inexpliset [sic] thing.”29 To Manning, “free governments” meant local control. He and other farmers worried about power concentrated in the hands of few, and power situated in distant urban locations.

Manning had good reason to worry. A powerful new federal government could, among other things, quell dissent and suppress working-class movements. It could also draft repressive legislation, as exemplified when Samuel Adams helped draft the Massachusetts Riot Act of 1786, designed to disperse and to control uprisings. The weight of this act came down on Daniel Shays, a former captain in the Continental Army who had fought at Bunker Hill and who in 1786 led a rural uprising of indebted farmers in rural western Massachusetts. Several hundred farmers armed themselves and marched on the courts in Springfield and Worcester (much as farmers had done in 1774) but were driven back by an army that was paid for by wealthy Boston merchants. Outnumbered, the men took flight, and took refuge in Vermont. Many of Shays’s cohort surrendered and were put on trial; some were sentenced to death. Shays himself was pardoned in 1788.

Shays’s discontent was shared by others. From 1798 to 1800, liberty poles were raised across the land in opposition to the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798—a draconian law passed under President John Adams that allowed for the imprisonment of anyone who criticized the government. When the poles went up this time, the federal government cut them down and used the new law to go after those who had initiated the actions.

In Dedham, Massachusetts, David Brown rallied his community in 1798 to install a Liberty Pole that included text that read “No Stamp Act / No Sedition Act / No Alien Bills / No Land Tax / Downfall to the Tyrants of America / Peace and Retirement to the President / Long Live the Vice President.”30 For his actions, Brown was charged with sedition, fined $480, and jailed for eighteen months.

Examples of resistance were not limited to Massachusetts: poor people challenged federal authority all across the new nation in the late eighteenth century, from the Regulators in North Carolina to the Green Mountain Rebels in Vermont, and many more. Yet what was lacking was class solidarity between the rural poor and the urban poor. Artisans did not support Shays’ Rebellion, nor did they support the tenant uprisings in rural New York in 1766.31 Working-class men did not embrace Mary Wollstonecraft’s “Vindication for the Rights of Women” (1792), and neither did they support the slave insurrection led by Gabriel Prosser in Virginia in 1800.32 Meanwhile, free African Americans in Boston offered to “assist” Shays’ Rebellion, but they did so not by joining the side of debt-ridden farmers but by offering their assistance to the militias in putting it down.33 These tensions left working-class people divided and it left them weak. To paraphrase Alfred F. Young, it left the multiple radicalisms of the revolutionary era separate from one another.34 And it left a revolution only partially completed.

Unidentified artist/s, Stowage of the British Slave Ship “Brookes” Under the Regulated Slave Trade Act of 1788, etching, ca. 1788, (LC-USZ62-44000, Library of Congress)