IN THE LATE 1700S, abolitionists in the United States and the UK harnessed the power of the print illustration. Lithographs and illustrations became the predominant medium owing to the ease of reproduction and because they could be readily disseminated to a wide audience. Illustrations were also found in the multitude of antislavery newspapers and pamphlets, which in turn were spread across the U.S. North and the South. All of these images largely focused on three distinct tactical campaigns: creating empathy for those held in slavery; celebrating heroic African individuals; and vilifying the Southern character and way of life that endorsed the institution of slavery.1

The initial goal for the visual artists was to attempt to persuade a reluctant public to rally against an institution and ideology that had permeated and indoctrinated much of the American public for more than two centuries. This was no easy task, so abolitionists in the United States turned to another campaign for inspiration. The British abolitionist movement, which had begun in earnest as a small gathering of a dozen citizens in the 1780s, galvanized much of their country in only a few decades to rally against the slave trade in general and specifically England’s role as the leading Atlantic slave-trade merchant from the 1730s to the early 1800s. The movement had perfected the use of visual graphics in its campaign, and many of the same tactics and images would serve the American cause.

However, the strategy for combating slavery differed in the United States. Slavery in England was more abstract, as relatively few African slaves were physically present on English soil. In the United States, slavery was part of the very fabric of life. U.S. abolitionists could expect opposition to their efforts in the South, but they also met a great deal of hostility in the North. Much of the industry of the North was explicitly tied to the Southern slave system; Northern textile mills and shipping merchants reaped tremendous profits from slave-grown cotton, which by the 1830s had become the nation’s most valuable export crop.

“King Cotton,” as it had come to be known, helped fuel the expansion of slavery within the United States as slaveholders moved westward in search of new fields for this highly profitable crop.2 Eli Whitney’s invention of the cotton gin in 1793 no longer limited the crop’s range to coastal regions. Southern planters relied heavily on investments from Northern businesses to help finance their expansion of cotton production. As cotton-derived industries in the North increased, so did the entire industrial sector, especially in New England. The same pattern was duplicated in England, where the textile factories were reliant on imported cotton.

The abolitionist movement attacked not only Southern slaveholders, but also the economic interests of the ownership class throughout the United States and abroad. Abolitionists were well aware of the inherent class issues at stake. Leading abolitionist voices, including Wendell Phillips, Henry Highland Garnet, William Lloyd Garrison, Lydia Maria Child, and Frederick Douglass, thus attacked not only the slave owner, but also the propertied class that profited from slavery’s existence.

Abolitionists placed their lives on the line by confronting slavery. The Georgia House of Representatives placed a $5,000 reward for the capture of William Lloyd Garrison, the white abolitionist and founding editor of The Liberator. In his hometown of Boston, Garrison was beaten and dragged through the streets by a mob in 1835.3 Between 1833 and 1838, the abolitionist press reported more than 160 instances of violence against antislavery groups, which included the murder of Rev. Elijah P. Lovejoy, a white newspaper editor from Alton, Illinois, who was shot defending his presses against a mob in 1837.4 This was the climate that abolitionists operated in when they tried to reach the public with an antislavery message.

Description of a Slave Ship

Though their enemies were everywhere, American abolitionists also had their allies, especially in the British movement. Galvanized by a fiery young clergyman named Thomas Clarkson, a small group of abolitionists in London formed the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade (SEAST) in 1787 and set out to dismantle the institution that was tied to the political, cultural, and financial structure of the British Empire.

Clarkson’s primary role was to gather evidence about the slave trade to make a strong case to the public and to Parliament on why the practice should be abolished. He traveled to seaport towns across England and visited government buildings and merchant halls to obtain records on slave ships. There, he sought the details of expeditions, mortality rates, ship rolls, and names of those employed. He also sought out captains and merchants of the slave vessels, but they refused to talk to him once they realized his motives.

Undeterred, Clarkson sought out the common seamen who worked on the ships, and there he found allies. Seamen told Clarkson everything he wanted to know about the transport of slaves. They recounted the horrific conditions that they had witnessed, the reality that slaves faced—cramped conditions, beatings, deaths—as well as their own hardships under the brutal duress of the ships’ captains. It was damming evidence, and merchants tried in vain to counteract it and convince the public that slave ships were safe, hospitable, and in the best economic interests of the nation and her colonies. Clarkson pressed on and convinced a number of seamen to testify before Parliament, yet he also employed visuals to respond to the pro-slavery argument. His evidence took the form of a blueprint: an architectural rendering of the slave ship Brookes.

The image—commonly referred to as Description of a Slave Ship—visualized 294 Africans chained next to one another to illustrate the claustrophobic spaces beneath the decks. This was a view the English public could not see when slave ships were docked in its harbors. Ironically, the graphic underestimated the true horror of the Brookes, which carried upward of 740 slaves at its peak, not 294, and had a mortality rate of 11.7 percent.5 Nonetheless, the image was not simply about the Brookes: it was about the slave trade generally and Britain’s primary involvement in it. Description of a Slave Ship was meant to incite shock, create sympathy for those held captive, and spur people to become involved in the antislavery movement.

William Elford, Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, Plymouth Committee, Plan of an African Ship’s Lower Deck with Negroes in the Proportion of only One to a Ton, January 1789 (Bristol Record Office)

The image came from an unlikely source: The British government had sent Captain Parrey of the Royal Navy to Liverpool to record the dimensions of various slave ships, one of which included the Brookes—named after its owner, the merchant Joseph Brookes Jr.6 The Plymouth and London committees of SEAST obtained Parrey’s research and, realizing its potential, used it to create graphic abolitionist propaganda. SEAST member William Elford made the first image in November 1788. His design was simple and depicted the Brookes’s lower deck, with two columns of text below the image describing the ship and urging the public to take action.

The image itself was powerful, but its dissemination and its adaptability are what made it so effective. Some 1,500 copies of the image were printed and disseminated in Plymouth in early 1789. Copies were also sent to the London Committee, which began printing their own version of the Brookes design.7 The image also crossed the Atlantic. In May 1789, Mathew Carey published 2,500 copies of the Brookes image on a broadside in Philadelphia. Commenting on the graphic’s success, Carey wrote, “We do not recollect to have met with a more striking illustration of the barbarity of the slave trade.”8

The most famous adaptation of the image came from the London committee of SEAST, where Thomas Clarkson likely oversaw the design changes. This version magnified the effects of the image; instead of showing one view of the Brookes, it showed seven. Underneath the illustrations, four columns of finely printed text described the physical dimensions of the ship, the number of slaves stowed, and a personal account by Dr. Alexander Falconbridge—a sharp critique of the abysmal conditions that seamen faced on board the slave vessels.9

The brilliance of the image was multifaceted. The stark graphic alone communicated an antislavery message that could incite anger and compassion. The text was powerful but also small enough as not to distract from the graphics. It served as written evidence to back up the imagery for those who took the time to read it.

Combined, the image and text served as evidence, mirroring Clarkson’s efforts when SEAST sent him out to seaport towns on fact-finding missions. More important, Clarkson, Elford, and others who contributed to the design process made the important decision to create an image that did not point the finger at working-class people.10 The image called for justice both for the enslaved Africans whose labor was stolen and the British seamen whose labor was exploited. By simply depicting the architectural design of the ship and the means by which slaves were stored, the image pointed the finger most prominently at the slave system’s architect—the slave merchant—as the main culprit. Marcus Rediker, author of The Slave Ship: A Human History, explains:

Here was the hidden agent behind the Brookes, the creator of the instrument of torture. He was the one who imagined and built the ship, he was the ultimate architect of the social order, he was the organizer of the commerce and the one who profited by the barbarism.11

In one fell swoop, the image addressed both race and class.

SEAST widely disseminated the image and provided copies of the London edition of the broadside to every MP prior to his vote on the slave trade on May 11, 1789.12 They also included a copy of Clarkson’s text, The Substance of the Evidence of Sundry Persons on the Slave-Trade Collected in the Course of a Tour Made in the Autumn of the Year 1788—a collection of twenty-two interviews of seamen who had taken part in or witnessed the slave trade. SEAST worked closely with MPs and developed important allies, most notably William Wilberforce, who was the most vocal antislavery advocate within the halls of government. Not surprisingly, Wilberforce understood the power of images and abolitionist propaganda, and he had a wooden model made of the Brookes (complete with painted images of slaves on the decks) so that he could present it to his colleagues in the House of Commons as a means to strengthen his argument.

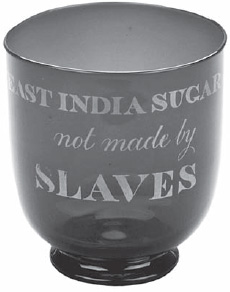

Blue glass sugar bowl, ca. 1830, Bristol, England (British Museum)

In addition, 8,000 copies were printed and distributed around England and beyond from 1788 to 1789.13 Abolitionists in Paris, Glasgow, Edinburgh, New York, Philadelphia, Providence, Newport, and Charleston would distribute copies or print their own versions of the design. Rediker writes, “The Brookes became a central image of the age, hanging in public places during petition drives and in homes and taverns around the Atlantic.”14

All of this graphic agitation produced results. Within five years after forming SEAST, abolitionists in the UK had pressured the House of Commons to pass its first law against the slave trade in 1792. Adam Hochschild writes:

The issue of slavery had moved to center stage in British political life. There was an abolition committee in every major city or town in touch with a central committee in London. More than 300,000 Britons were refusing to eat slave-grown sugar. Parliament was flooded with far more signatures on abolition petitions than it had ever received on any other subject.15

Other victories would follow. The Slave Trade Act of 1807 led to the banning of African slaves in the British colonies, and their transport to the United States in 1808, although slaves continued to be illegally transported for years to follow. In the British West Indies, slavery was abolished in 1827 (formalized in the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833) and in the French colonies fifteen years later. All of these victories in the UK would inspire their American counterparts. At a historic meeting of antislavery crusaders, Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison met with Clarkson in England as he approached the twilight of his life. Clarkson had spent sixty years of his life organizing against slavery and told his visitors, “And if I had sixty more they should all be given to the same cause.”16 Within British and American abolitionism, ideas, tactics, and images crossed the Atlantic in a shared coalition against slavery.

The American Campaign

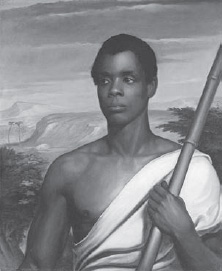

Whereas the iconic images of the British abolitionist campaign focused largely on creating a sense of empathy for African slaves, the U.S. campaign expanded upon that concept and added other visual tactics of moral persuasion. In the 1830s, U.S. abolitionist prints began documenting events that celebrated heroic African individuals. The Amistad slave ship mutiny in 1839 provided artists with a dramatic story and focal point to capture the imagination of the public.

The Amistad mutiny had occurred off the coast of Cuba, when fifty-three African men and women who had been illegally sold into slavery rose up against their captors aboard the Spanish ship La Amistad, killing both the captain and the cook and taking the rest of the crew hostage. The cook had taunted the slaves, telling them they were to be killed and later eaten by the Spanish. Believing the threat, the slaves—led by Sengbe Pieh, who was often referred to by his Spanish-given name Joseph Cinquez or Cinqué—violently overthrew their captors. The liberated slaves demanded that the ship be sailed to Africa, but the Spanish crew wound up deceiving them by altering the ship’s course to the north during the evenings. Eventually, after two months at sea and facing near starvation, a patrolling American naval crew off the coast of Long Island captured the ship. The slaves were taken into custody in New Haven, Connecticut, and charged with murder and piracy.

Many observers believed the remaining slaves who survived the mutiny would face certain death. However, a U.S. Supreme Court trial followed, in which former president John Quincy Adams, acting as part of the legal team that defended the African slaves, won a landmark decision resulting in the slaves’ freedom and return home to Sierra Leone.17 Sengbe Pieh, the charismatic and powerful leader of the mutiny, became a central figure throughout the trial and was celebrated widely by the abolitionist cause.

Several portraits of Pieh were created during the trial, the most notable being one commissioned by Robert Purvis, a black abolitionist from Philadelphia. Purvis hired a local artist, Nathaniel Jocelyn, to create the painting. Instead of portraying Pieh in his cell as a prisoner, as a previous portrait by James Sheffield had done, Jocelyn depicted Pieh as a free and noble individual standing before an African landscape. Jocelyn’s portrait, entitled Cinque, was meant to portray an African individual in a dignified manner in order to garner public support for the imprisoned slaves. In addition, John Sartain helped increase the image’s circulation by producing five hundred impressions of a mezzotint copy of the painting that were sold and helped raise funds for the defense committee during the trial.18

Nathaniel Jocelyn, Cinque, 1839 (New Haven Colony Historical Society, New Haven, CT)

Jocelyn was also purported to be involved in a plot to help break the Amistad slaves out of jail if the court ruled against them. Fortunately, this was not needed. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of Adams’s argument that the Africans had been kidnapped and had acted in self-defense and could not be classified as slaves. In 1841, thirty-five survivors of the original fifty-three boarded a ship back to Africa and to freedom.

Jocelyn’s painting would continue to champion the abolitionist cause even after the court victory. Robert Purvis submitted the painting to the Artists Fund Society in Philadelphia. To his dismay, it was rejected, a decision that drew the wrath of the abolitionist press. The Pennsylvania Freeman reported:

Why is the portrait denied a place in that gallery? . . . The negro-haters of the north, and the negro-stealers of the south will not tolerate a portrait of a negro in a picture gallery. And such a negro! His dauntless look, as it appears on canvas, would make the souls of slaveholders quake. His portrait would be a standing anti-slavery lecture to slaveholders and their apologists.19

The rejection of the portrait, despite the widespread interest in and newspaper coverage of the Amistad court trial, led some abolitionists to question their tactics. The portrait of Pieh holding a bamboo cane had been left open to interpretation: was the cane a weapon, or was it a reference to his enslavement in the Caribbean? Abolitionists debated whether abolitionist art should portray the empowerment of African individuals, especially when it came to depicting violence and slave uprisings.20 This echoed debates within the broader movement itself, where white activist leaders differed over whether slaves could or should participate in their own liberation.

In the print realm, another visual tactic of moral persuasion employed by abolitionists in the United States was to attack the character of the antebellum South. Bernard F. Reilly Jr. notes that “abolitionists carefully developed and cultivated an image of the South as a world in decline, a place of deteriorating physical and moral conditions, exhausted soil, and a dispirited working class.”21 In the mid to late 1830s, a multitude of antislavery books and newspapers appeared in the North that were designed both to inform and to awaken Northerners from their complacency toward slavery. These publications utilized print illustrations and woodcuts to complement the text and to help expose the cruelty inflicted upon slaves.

Hannah Townsend and Mary Townsend, The Anti-Slavery Alphabet (Philadelphia: Printed for the Anti-Slavery Fair, 1846; American Antiquarian Society)

Prominent abolitionist publications included The Anti-Slavery Record, Human Rights, Emancipator, The Liberator, and The Anti-Slavery Almanac, along with publications directed toward a children’s audience such as the Anti-Slavery Alphabet (1846) and the magazine The Slave’s Friend.

Theodore Weld’s American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses, published by the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1839, was a scorching indictment of the institution of slavery. The document was an anthology of testimonies from slaveholders and former slaveholders in the form of written statements, judicial testimonies, speeches by politicians, and clippings selected from Southern newspaper articles.

In 1835, abolitionist groups launched the “great postal campaign,” mailing antislavery papers and pamphlets to every town in the country. In an action that severely threatened civil liberties, President Andrew Jackson responded by urging Congress to ban all abolitionist literature from the U.S. mail. Jackson also insisted that the names of sympathetic Southerners who had received abolitionist mail be made public, thereby compromising their physical safety. In an expression of the hatred that he felt toward abolitionists, Jackson purportedly stated that they should “atone with their lives.” Indeed, this was the climate in which abolitionists operated, making their gains against slavery all the more remarkable. In South Carolina, a $1,500 reward was offered for the arrest of anyone distributing William Lloyd Garrison’s paper The Liberator, and Georgia had passed a law allowing the death penalty to be enacted against a person who encouraged slave insurrections through printed material.22

Unidentified artist, New Method of Assorting the Mail, As Practised by Southern Slave-holders, 1835 (LC-USZ62-92283, Library of Congress)

In response to the abolitionists’ postal campaign, many Southern postmasters seized antislavery mail, and in Charleston, South Carolina, a mob raided a post office in the middle of the night and set fire to the bags of mail from the abolitionists. A print mocking the midnight raid, entitled New Method of Assorting the Mail, As Practised by Southern Slave-holders, blasted the participants in this action.

The image acts as a quasi-eyewitness account and depicts the crowd burning various abolitionist papers. On the side of the post office building, a Wanted poster hangs for the American Anti-Slavery Society founder Arthur Tappan. The lithograph was circulated with another print vilifying the slaveholder, entitled Southern Ideas of Liberty.

In this image, a Southern judge, depicted with horns and his foot resting upon the Constitution, sentences a white abolitionist man to the gallows before a restless mob. Both prints are unsigned, but may be the work of J.H. Bufford of Boston, whose lithographic style closely resembles the prints.23

Unidentified artist, Southern Ideas of Liberty, 1835 (LC-USZ62-92284, Library of Congress)

The fact that the two prints remained anonymous suggests that the artist felt safer not revealing his or her identity. Indeed, the experience of Charles Sumner exemplifies the physical risks faced by opponents of slavery. Sumner, a Massachusetts senator who was arguably the Senate’s leading opponent against slavery, drew the wrath of Southern politicians. Prior to being elected to Congress, Sumner was an attorney whose efforts included working with African Americans in an attempt to desegregate the Boston public schools. As a senator, he spoke out against the spread of slavery into the Kansas Territory, and in a caustic speech blasted South Carolina senator Andrew P. Butler for his support of slavery’s expansion. On May 22, 1856, Senator Butler’s cousin, Preston Brooks, U.S. representative from South Carolina, retaliated. As Sumner sat at his desk on the floor of the U.S. Senate, Brooks attacked Sumner and beat him unconscious with a walking cane. Sumner’s severe injuries would keep him out of the Senate for the next three years.

John L. Magee, Southern Chivalry—Argument versus Clubs, 1856 (Boston Athenaeum)

The attack on Sumner helped to widen the divide between the North and the South that would lead to secession and war. Historians James Oliver Horton and Lois E. Horton recount the contrasting views of the attack:

Five thousand gathered in the New York City Tabernacle to express their outrage at what most considered an act of southern violence. This perception seemed to be confirmed when southern supporters celebrated Brooks’s attack. The Richmond Whig called it an “elegant and effectual canning,” and southern groups, including students at the University of Virginia, presented Brooks with a number of ornately carved canes.24

Prints depicting the caning of Charles Sumner quickly emerged.25 One notable image was John L. Magee’s 1856 lithograph Southern Chivalry—Argument versus Club’s [sic].

The caricature portrays Brooks savagely beating the defenseless Sumner as he lays bloodied on the floor holding a pen and a document against slavery’s expansion in Kansas. In the background, Congressman Lawrence Keitt of South Carolina brandishes a cane to hold back other members of Congress who might come to Sumner’s aid, yet most smile in amusement. Magee—a Philadelphia-based engraver and lithographer—projects an antislavery message. His goals were akin to those of others who had visualized an abolitionist stance: persuade the public to rally against the institution of slavery. This gentle form of persuasion—as visually striking as it was—would fall short in the United States, most notably in the South. The issue of slavery would be decided through war.