Photographing the Past During the Present

IN EVERY PHOTOGRAPH, the photographer frames the scene; thus, an image can often tell us more about the person behind the camera than those depicted in front of it. Images can be doctored, and they can be staged. An image can blur reality, or the photographer can simply ignore one scene in favor of another. All of these factors mean that a photographic image should not be taken at face value. Instead, an image should be cross-examined, along with the ideology of the artist and the political and cultural climate in which the artist worked. This is especially important for historical photographs that are well circulated—images that have been republished over and over and have the power to affect the present by serving as visual guides and quasihistorical records of past events, peoples, and cultures.

An examination of the widely known white photographer Edward S. Curtis and the much lesser-known, if not obscure, Native photographer Richard Throssel (Cree), reminds us of the importance today of looking at the social conditions, the politics, the funding, and the motives that hide behind the images. Curtis documented more than eighty Native tribes during a thirty-year span from the position of an outsider; Throssel, a Cree Native who was given land and formally adopted by the Crow, took more than one thousand images of the Crow tribe as an insider to the culture that he visualized for future generations. Each photographer created his own distinctive body of work, yet the parallels and divergences of their two approaches are as significant as the images that they captured with their cameras.

![]()

Edward S. Curtis began photographing Native peoples in the West in the late 1890s, a decade or more after the reservation system had been firmly entrenched, but one would never sense this by looking at his images. Curtis is famous (if not infamous) for portraying Native people as untouched by white society: before encroachment, acculturation, and reservations.

His drive to document Native people was similar to that of many other white photographers, researchers, and ethnologists who feared that the sudden shift from traditional cultures to the reservation era would cause Native cultures and perhaps the people themselves to “vanish”—that they would either be absorbed into the white mainstream or annihilated. The irony and hypocrisy of this sentiment is hard to ignore: European Americans fretting over the loss of a Native culture and way of life that they had sought and helped to destroy.

Forced acculturation took many forms. Native customs and religions were banned, and children were separated from their parents and their communities and sent away to boarding schools. Adult men who had been warriors and buffalo hunters were coerced into becoming farmers and ranchers as the West became industrialized and was populated by more and more white settlers. Gerald McMaster notes that enforcing this sudden transition was asking the impossible: “It had taken centuries for Europeans to develop in this direction, but Native peoples were expected to change overnight.”1

![Edward S. Curtis, The Offering—San Ildefonso, ca. 1927, photogravure (LC-USZ62-61129, published in The North American Indian / Edward S. Curtis. [Seattle, Wash.]: Edward S. Curtis, 1907–30, Suppl. v. 17, pl. 586; Library of Congress)](images/f0050-01.jpg)

Edward S. Curtis, The Offering—San Ildefonso, ca. 1927, photogravure (LC-USZ62-61129, published in The North American Indian / Edward S. Curtis. [Seattle, Wash.]: Edward S. Curtis, 1907–30, Suppl. v. 17, pl. 586; Library of Congress)

At the same time that the United States was forcibly denying the practice of Native traditional culture and religions, a mad rush of photographers and scientists came out west to document what they feared would soon no longer exist. James C. Faris writes that the impulse to document occurred only once it was safe to do so:

Now a people successfully conquered, the photographs for public consumption of Native Americans were to be sentimental and nostalgic (mighty warriors as victims) but also shells of their former selves—no longer a threat to European-American expansionism and evidence of the success of European American expansionism, of Manifest Destiny. This meant that Native Americans could not appear happy, prosperous, flourishing—or even simply persisting or surviving—they had to appear “vanishing.”2

Edward S. Curtis helped propagate this myth. From the late 1890s to 1930, Curtis took more than 40,000 photographs of Native peoples, a number of which were included within his twenty-volume folio set The North American Indian. Limited to five hundred sets, the folios were sold by subscription for either $3,000 or $4,000, placing the photographs in the hands of only wealthy elites who could afford the steep cost. Curtis’s work itself was funded by the financier J.P. Morgan, championed by Theodore Roosevelt, and his subscribers included Andrew Carnegie and the railroad magnates James Hill and Edward Harriman—all of whom were instrumental in advocating, orchestrating, and financing western expansionism.3 Curtis’s work, although rooted in elite culture, also reached a popular audience. Reprints of his images could often be found within magazine articles. He gave visual lectures and even performed a musical. His singleminded drive is hard to comprehend. Curtis crossed the continent by train more than 125 times, dedicated to his work at the cost of his marriage, finances, and health.4 Curtis died in 1952, leaving his indelible pictorial record of Native people and cultures to the public to decipher. Popular interest in his work goes through waves, as the Standing Rock Sioux scholar Vine Deloria Jr. noted:

Everyone loves the Edward Curtis Indians. On dormitory walls on various campuses we find noble redmen staring past us. . . . Anthologies about Indians, multiplying faster than the proverbial rabbit, have obligatory Curtis reproductions sandwiched between old clichés about surrender, mother earth, and days of glory. This generation of Americans, busy as previous generations in discovering, savoring, and discarding its image of the American Indian, has been enthusiastic in acquiring Curtis photographs to affirm its identity.5

Yet within the same explanation of his work, Deloria cautions that Curtis’s images “[suggest] a movie still rather than a historical event.”6 In this regard, his photographs appeared more like a Hollywood western film and were a far cry from the realities that Native people faced living on reservations. Printed in sepia tones with India ink and shot with a soft focus, Curtis’s photographs froze his subjects in the distant past.

Common images within Curtis’s arsenal included portraits of stoic Native Americans staring into the lens of the camera or isolated in a natural setting with no evidence of reservation life or the industrialization of the West. The often-reproduced The Vanishing Race—Navaho (1907) from volume 1 of The North American Indian presents a typical formula.

![Edward S. Curtis, Vanishing Race—Navaho, ca. 1904, photogravure. (LC-USZ62-37340, published in The North American Indian / Edward S. Curtis. [Seattle, Wash.] : Edward S. Curtis, 1907-30, Suppl. v. 1, pl. 1. ; Library of Congress)](images/f0051-01.jpg)

Edward S. Curtis, Vanishing Race—Navaho, ca. 1904, photogravure. (LC-USZ62-37340, published in The North American Indian / Edward S. Curtis. [Seattle, Wash.] : Edward S. Curtis, 1907-30, Suppl. v. 1, pl. 1. ; Library of Congress)

A line of Native people on horseback slowly walks off into the distance toward the mountains, “vanishing” into nature. With their backs turned to the camera, their individual identities become erased, reinforcing Deloria’s critique that we are viewing a scene from the director’s vision and not a true documentation of life at the time. The altered background only adds to the sense of a fabricated scene. Above the mountains, Curtis retouched the photograph and added a white glow to provide the images with a heightened sense of drama. This type of photographic manipulation has drawn its share of criticism, as Lucy R. Lippard explains:

Curtis is attacked most often, and most legitimately, for his lack of ethnographic veracity. . . . He staged scenes, routinely retouched and faked night skies, storm clouds, and other dramatic lighting effects. He erased unwelcome signs of modernity, although late in life he finally became resigned to change and photographed people as they were. In his heyday, however, he was an emotional formalist, not an objective documentarian. Curtis was distressed when he arrived “too late” and found customs and ceremonials no longer in use. With the help of the tribes, he sometimes re-created them. When working in the Pacific Northwest, he carried with him wigs (for those who now had white man’s haircuts), “primitive” clothes, and other out-of-date trappings.7

Does this mean that we should completely dismiss Curtis’s massive body of work? Deloria is helpful here when he notes, “Perhaps Curtis was less a liar and more an American dreamer, who felt impelled—as we all do—to create a reality for himself in lieu of the substance of observable things.”8 Likewise, George P. Horse Capture (Gros Ventre) adds, “Real Indians are extremely grateful to see what their ancestors looked like or what they did” and notes that one of Curtis’s images is that of his great grandfather.9 Curtis himself remarked that a number of tribes supported his efforts in preserving a pictorial record for future generations: “Tribes that I won’t reach for four or five years yet have sent word asking me to come and see them.”10

![Edward S. Curtis, Upshaw—Apsaroke, ca. 1905 (LC-USZ62-124178, published in:The North American Indian/Edward S. Curtis. [Seattle, Wash.]: Edward S. Curtis, 1907–30, Suppl. v. 4, pl. 139; Library of Congress; Christopher M. Lyman writes in The Vanishing Race and Other Illusions, “A.B. Upshaw, a Crow Indian, worked for Curtis as an interpreter. For this portrait he wore a costume so as to appear ‘Indian’ to Curtis’s viewers.” See The Vanishing Race and Other Illusions: Photographs of Edward S. Curtis, New York: Pantheon Books, 1982, 92)](images/f0052-01.jpg)

Edward S. Curtis, Upshaw—Apsaroke, ca. 1905 (LC-USZ62-124178, published in:The North American Indian/Edward S. Curtis. [Seattle, Wash.]: Edward S. Curtis, 1907–30, Suppl. v. 4, pl. 139; Library of Congress; Christopher M. Lyman writes in The Vanishing Race and Other Illusions, “A.B. Upshaw, a Crow Indian, worked for Curtis as an interpreter. For this portrait he wore a costume so as to appear ‘Indian’ to Curtis’s viewers.” See The Vanishing Race and Other Illusions: Photographs of Edward S. Curtis, New York: Pantheon Books, 1982, 92)

Yet this support was far from unanimous. Many Native tribes and individuals resisted the camera, whether it was Curtis or other white photographers determined to document their culture. Some individuals, such as the Oglala Lakota warrior Crazy Horse, refused to allow his photograph to be taken; many others believed that the camera was a “shadow catcher” and was to be avoided at all costs. Curtis had rocks thrown at him on a number of occasions, and arguably his most interesting photographs (and ones that are the least frequently reprinted) are those that document individuals covering their face and taking other actions to avoid the camera.11 Lippard notes that resistance to the camera was not an isolated instance:

By the turn of the century, Indians were already officially protesting the presence of photographers. In 1902 the Hopi restricted photographers to a specific area so they could not interfere with the ceremonies. In 1910 they banned photography of the ceremonies altogether, as a result of a trip to Washington where they saw “a congressional hearing room plastered with a selection of photographs of religious ceremonies . . . [ which] they found to their dismay, were being used by Bureau officials and missionaries to discredit their religion.12

George L. Beam, Taos Pueblo Fiesta Races Dancers, ca. 1920–1930, GB-7852 (Western History/Genealogy Department, Denver Public Library)

Today, in many pueblos and reservations in the Southwest, outsiders are completely banned from taking photographs, results of a lingering memory of how photography was used against Native people.13

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (Flathead-Cree-Shoshone) explains: “Government surveyors, priests, tourists, and white photographers were all yearning for the ‘noble savage’ dressed in full regalia, looking stoic and posing like a Cybis statue. . . . We cannot identify with these images.”14 Photographer Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie (Seminole-Muscogee-Diné) adds that the photographs that perpetuated the myth of the “noble savage” became the standard pictorial representation, whereas other possible focuses were virtually ignored: “The photographic evidence of U.S. genocidal practices is not extensive, if there is no evidence of genocide then there was no genocide.”15 In contrast, Tsinhnahjinnie notes:

The focus of my relatives was the reality of survival, keeping one’s family alive. Time to contemplate Western philosophy or the invention of photography was, shall we say, limited. Because of the preoccupation with survival, Native people became the subject rather than the observer. The subject of judgmental images as viewed by the foreigner—images worth a thousand words. As long as the words were in English.16

As with every moment in history, there are exceptions to the rule. A small number of Native people did become accomplished photographers and documented their communities in a way that white photographers could not—as insiders. Native photographer Richard Throssel worked during the same era as Edward S. Curtis, and presented a view that went beyond the “vanishing” notion by responding to present-day realities that existed in the lives of those he was documenting.

Throssel was born in 1882 in Marengo, Washington, and grew up in Roy, a small farming community just east of Olympia. His Cree grandparents had been employees of the Hudson Bay Company and moved to Washington in 1841. Throssel, however, had to move away from home due to health reasons. He suffered from rheumatism, and in 1902, at the age of twenty, he sought out a drier climate and moved to the Crow Reservation in Southeast Montana, where he lived until 1911.17 His first job was as a clerk for the Crow Agency Offices, where he was one of many newcomers to the area. The Crow Reservation was a hub of activity for outsiders, non-Native researchers, ethnologists, anthropologists, and artists alike who sought to learn more about the traditions and cultures of the Crow that they feared would soon be lost to acculturation. Also working on the reservation and also employed at the Crow Agency Offices were the European American photographers Fred E. Miller and Lorenzo Creel, along with Joseph Henry Sharp. Sharp, who would later become one of the founders of the Taos School of Art, documented the Crow through paintings and photography.18 All told, more than fourteen professional and amateur photographers—including Edward S. Curtis, who visited the reservation between 1905 and 1909—documented the Crow Reservation between 1900 and 1910 in what some residents described as a “stampede of photographers.”19

All of these individuals had an influence on Throssel, who quickly taught himself the medium. He began photographing the Crow by 1904, taking advantage of his unique position. As a Native person and as an adopted member of the Crow, Throssel gained access to events, people, and ceremonies of the Crow and other tribes that others would not have been granted permission to attend, let alone photograph. In 1909 he photographed the Northern Cheyenne Massaum ceremony, also termed “The Animal Dance”—a five-day ritual that involved participation by the entire tribe. Peggy Albright, author of the biography of Richard Throssel, Crow Indian Photographer, writes:

It would be difficult to overstate the significance of this photographic image, a recording of one of the Cheyenne’s rarest and most sacred ceremonies, which was then banned by government regulation. This image and twelve others taken by Throssel that year comprise the first visual records of the Massaum and the only known images of the 1909 offering. Throssel’s description also represents the first eyewitness account in literature. In addition to these images, he took seven extremely rare images of the now-extinct Contrary Society, whose members also participated in the ceremony.20

One of Throssel’s signature images of the Massaum documents a group of nine people running across a field, some blowing through eagle-bone whistles.

Albright notes that this image could only have been made with the cooperation of his subjects, who told Throssel where to set up his camera to best photograph the event.21 This important image gave notice that, despite efforts to ban traditional customs and religious practices, Native people resisted many of these forced measures. Throssel gave a copy of this image to Curtis, and Curtis copyrighted it under his own name and published it within volume 6 of his folio The North American Indian.22

However, the photographs that set Throssel apart from Curtis and his other contemporaries are, ironically, photographs that both documented and encouraged acculturation: work that undermined tribal sovereignty. In 1909, Throssel was hired as a field photographer for the Indian Service (a position in which he reported to officials in Washington, DC) to document day-to-day living conditions, particularly health problems, within the reservation.23 Health issues such as tuberculosis and trachoma were at epidemic levels on a national scale, but they were even more severe on reservations, where poverty, lack of medical clinics, and crowded, unsanitary boarding schools only served to heighten the problem.24 Throssel’s photographs showed sick and dying individuals and acted as public-service messages to encourage healthier living habits.

Richard Throssel, Cheyenne Animal Dance, 1909 (Richard Throssel Collection, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming)

On the Crow reservation, Throssel worked under the direction of Dr. Ferdinand Shoemaker, a physician who previously had worked at the Carlisle Industrial School.25 The goal of their work was summed up by the commissioner of Indian Affairs, Robert G. Valentine, in his annual report:

A series of illustrated lectures for a traveling health exhibit are being prepared. A special physician and photographer are in the field securing photographs from which these stereopticon slides and moving pictures can be made. This exhibit will be sent to the different schools and reservations. One of the most important results of this educational work will be that it will instruct the employees at the schools and agencies of the Indian Service as to the methods of preventing disease, and in this way unite the entire service in the health campaign.26

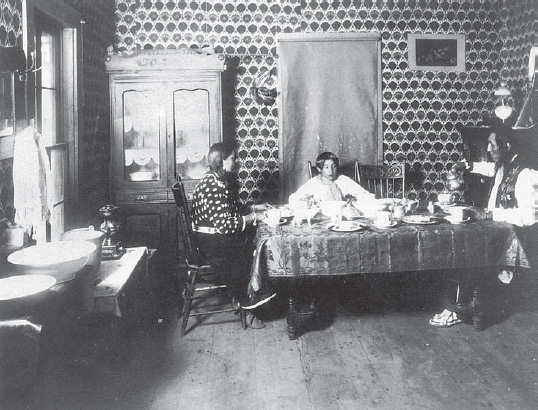

One of Throssel’s most persuasive images from the series is Interior of the Best Kitchen on the Crow Reservation.

The photograph documents a Crow family within a modern kitchen who refuse to engage with the camera and appear at first glance to be out of place, although buildings of these types were becoming increasingly common on reservations. However, the interior used in the photograph was indeed out of place: it was a stage set. Prior to the photographic shoot, a room with walls and a floor were constructed, and furniture, wallpaper, and decorations were added. A roof was never built, for the sun provided better light for Throssel’s camera.

Richard Throssel, Interior of the Best Indian Kitchen on the Crow Reservation, 1910 (photo no. 4644, Smithsonian Institution, National Anthropological Archives)

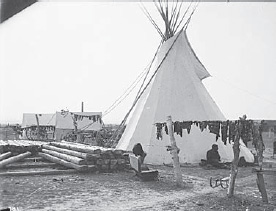

Viewers of the image at the time would never have known this was a staged image. Instead, they would see an instructive image that discouraged traditional living habits that were thought to be one of the main reasons behind the spread of diseases. They would have seen this image contrasted with other public-service images on what not to do: images of Crow members eating on the ground and sharing cups in a tepee, and images of passing of the pipe—a spiritual practice and part of the Crow Tobacco Society that was discouraged for fear of spreading disease.27

Richard Throssel, The Rustler, ca. 1911, (Richard Throssel Collection, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming)

It is ironic that Curtis’s staged images pictured a nostalgic look at traditional life, whereas the staged photographs of Throssel advocated for assimilation as part of a federal campaign to address the spread of disease.28 Yet while Throssel’s images backed federally imposed measures, they also addressed present-day realities and were meant to help his community and the overall health of Native peoples. Throssel’s images acted as a form of community activism. They responded to immediate needs, in stark contrast to Curtis’s images that revolved around his own self-interest and were intended to build up his folio, establish his reputation, and sell to a wealthy clientele. Throssel’s images reached a Native audience and were shown on fifty-two occasions to more than 10,000 people.29

Richard Throssel, Indian Sitting Outside Teepee with Meat Drying on Racks, ca. 1905–1911 (Richard Throssel Collection, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming)

Despite the success of the photographs, Throssel resigned from his position in February 1911. He complained justifiably that he was not given public recognition for his work, noting that the program director, Dr. Shoemaker, had received the bulk of the recognition.30 Soon after his resignation, Throssel and his family moved to Billings, Montana, where he established his own photography business and marketed his vast collection of photographs of the Crow to the public under his own name.

Richard Throssel, Plenty Coups—Crow, ca. 1907–1911 (Richard Throssel Collection, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming)

Here, Throssel’s work took another confounding turn: he marketed a series of photographs that could easily have been mistaken for the work of Edward S. Curtis. Throssel’s series of thirty-nine photographs, Western Classics from the Land of the Indian, focus upon a nostalgic look at Crow life. Throssel was well aware that a non-Native audience sought out these types of images, and he provided a set of images that followed Curtis’s mold: dramatic images of a “vanishing” culture, retouched photographs, and scenes that ignored reservation life and signs of industrialization.31

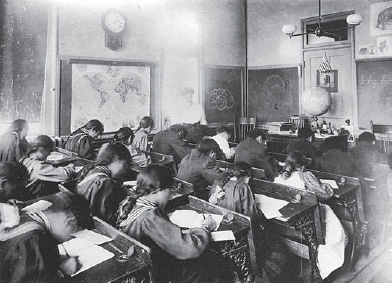

These images stood in sharp contrast to other photographs that Throssel had taken that were so significant for showing signs of modernization—images of tepees next to log materials for new construction, a portrait of Chief Plenty Coups standing outside his two-story home, and Crow children inside a reservation classroom.

Throssel, however, knew that white tourists and those who ordered his images by mail would not purchase his more realistic images, so he sold images in the “Curtis mold,” while still advertising himself as an insider to the people he documented. His Western Classics brochure included the information: “Richard Throssel is an Indian, Crow allottee No. 2358; Esh Quon Dupahs as the Indian knows him. He belongs to them. His home is among them. Their lives he knows, their traditions and folklore.”32 This text was included to give him additional credibility to his customers and to set him apart from his contemporaries.

Richard Throssel, School Room, Crow Indian Reservation, 1910 (photo no. 95-1384, (Smithsonian Institution, National Anthropological Archives)

Other facets of Throssel’s complex life indicate that his dedication was to his people. In 1924, Throssel ran for political office and was elected Yellowstone County’s representative to the nineteenth session of the Montana State Legislature. While in office, he advocated for increased sovereignty rights and land rights for Native people and spoke out against corporate power. He opposed opening up the Crow Reservation to the Big Horn Canyon Power and Irrigation Company, which wanted to generate hydroelectric power in the region. He also advocated for an increase in the metal tax for the large mining corporations to help pay for Montana’s schools—a tax initiative that the mining interests greatly resisted. In 1924, he achieved a major victory when the tax was enacted by a popular vote—a rare people’s victory over the massive Anaconda Copper Mining Company. Throssel’s short political career, which ended in 1928 when he was defeated in a primary, included introducing a bill that directed federal funds for health care for Native people in Montana, and persuading a four-year college (now Eastern Montana College) to locate its campus in Billings, in close proximity to the Crow Reservation, as opposed to another region in the state.33

Throssel’s concerns, whether expressed through his photography or his public service, were focused on the present, responding to the conditions that affected those within his community. In contrast, Curtis’s camera ignored the everyday realities that faced the people he was documenting. His images were selective, ignoring issues of modernization and issues of poverty. He even ignored everyday joys, choosing to overlook photographs of his subjects smiling, and opting instead for the stoic image of Native people. These images created lasting stereotypes and the damaging myth of a “vanishing people.” Throssel’s photography, in contrast, revealed a more accurate documentation of what life was like for the Crow in the early 1900s. He did not ignore the very real problems that existed on the Crow Reservation. His motives were to provide immediate help, yet his photographs (outside of his public-health images) reached a much smaller audience than Curtis’s work.

In fairness, both photographers created a complicated legacy, one open to an equal dose of compliments and criticism. We should not discredit the fact that many Native and non-Native people appreciated the extensive record of Native peoples that Curtis has left for the public, and neither should we downplay how invasive his camera and his methods were at times. It is best if we view both Curtis’s and Throssel’s work as complicated. Both bodies of work invite contemporary audiences to interrogate the past and the people who documented it with a more critical eye.