“I began taking pictures by proxy. It was upon my midnight trips with the sanitary police that the wish kept cropping up in me that there were some way of putting before the people what I saw there. A drawing might have done it, but . . . a drawing would not have been evidence of the kind I wanted.”

—Jacob A. Riis1

FROM THE LATE 1870s until his death in 1914, Jacob A. Riis was one of the leading voices in the tenement-reform movement. He was a police beat reporter for the New York Tribune who reported from an office directly across from police headquarters on Mulberry Street, in the heart of one of the roughest sections of the city. He was also the author of numerous books, including How the Other Half Lives (1890)—a bestseller that remained in print throughout his life. His other books included, among others, The Children of the Poor (1892), Out of Mulberry Street (1898), A Ten Years’ War (1900), The Battle with the Slum (1902), and Children of the Tenements (1903). Riis was also an amateur photographer whose work nonetheless became highly influential over time. He was one of the first people in the United States to photograph urban poverty and one of the first to utilize photographs together with text. Together these made an emotional appeal that urged his audience to become active in the tenement-reform movement. In the process, Riis helped launch a new genre—social documentary photography.

However, Riis was first and foremost a reformer, and a successful one at that. His many accomplishments during his lifetime included campaigns that led to the demolition of some of the most notorious tenement buildings in New York City, the establishment of truant schools, the building of small parks within tenement neighborhoods, the closure of police lodging houses, and the cleaning up of the Croton Reservoir—a filth-ridden location from which the city received its water supply.

Riis’s work was not without controversy or contradiction. His writings were littered with racist stereotypes and his photographs were often intrusive and undermined the individuality of his subjects. Indeed, much of his work addressed an audience that did not include the tenement residents themselves. Instead, Riis directed his work toward middle- and upper-class charity groups and government officials. For this reason, Riis is often maligned in our own time. However, simply dismissing Riis’s work would be a mistake. He created far too great of an influence in the tenement-reform movement, as well as the genre of photography, for his efforts to be negated.

![]()

To understand Riis we must understand the conditions that he sought to change. In the late 1800s, close to two-thirds of the city’s population (1 million out of 1.5 million) lived in tenement houses. Tenement neighborhoods stretched from lower Manhattan to Fifty-Ninth Street. Upward of 60,000 new immigrants—mostly Italians, Eastern and Southern Europeans, and Russians—arrived per month, making parts of the city, particularly the Lower East Side, one of the most densely populated places in the world.

Derelict buildings, overcrowding, and unsanitary conditions created a death rate that was astronomical—one in twenty and one in five or worse for children younger than five.2 Epidemics were rampant. Outbreaks of typhus, cholera, smallpox, and yellow fever killed thousands each year, and few government programs existed to assist those in need. Likewise, building codes were inadequate and those that were in place were rarely enforced. To remedy this void, upward of five hundred charity groups in New York City alone provided varying degrees of assistance.

Jacob A. Riis, Waiting to be Let into a Playground, ca. 1890 (Museum of the City of New York)

Riis exposed these conditions of the tenements through his writing, but he also turned to another medium: photography. His goal was simple: allow the public to see what he saw—to visualize the deplorable conditions, the crowded rooms, basement dwellings, taverns, and sweatshops that existed behind closed doors.

In 1877, Riis began asking friends and associates to follow him and the sanitary police into tenement buildings and take photographs late at night, when his party would break into a room unannounced and take pictures—or, what Riis referred to as evidence. Riis recalls:

I recall a midnight expedition to the Mulberry Bend with the sanitary police that had turned up a couple of characteristic cases of overcrowding. In one instance two rooms that should at most have held four or five sleepers were found to contain fifteen, a week-old baby among them. Most of them were lodgers and slept there for “five cents a spot.” There was no pretense of beds. When the report was submitted to the Health Board the next day, it did not make much of an impression—these things rarely do, put in mere words—until my negatives, still dripping from the dark-room, came to reinforce them. From them there was no appeal. It was not the only instance of the kind by a good many. Neither the landlord’s protests nor the tenant’s plea “went” in the face of the camera’s evidence, and I was satisfied. I had at last an ally in the fight with the Bend.3

Riis had a more difficult time convincing his friends to return to the tenement slums on a nightly basis, so he decided to learn the medium himself. In January of 1888, he paid $25 for a camera, tripod, plate holders, and a simple darkroom kit. However, he ran into technical limitations; cameras could not take photographs at night or within dark spaces, therefore making images within the dark tenement rooms and cellars next to impossible. His problem was solved when he came across a newspaper advertisement for a newly invented flash called Blitzlichtpulver—an explosive mixture of powdered magnesium and two other substances that created a bright blue light when it was ignited. To create a flash of light the powder was put into cartridges and shot from a gun. Riis wrote:

It is not too much to say that our party carried terror wherever it went. . . . The spectacle of half a dozen strange men invading a house in the midnight hour armed with big pistols which they shot off recklessly was hardly reassuring, however sugary our speech, and it was not to be wondered at if the tenants bolted through windows and down fire-escapes wherever we went.4

Jacob A. Riis, Lodgers in a Crowded Bayard Street Tenement—“Five Cents a Spot,” 1889 (Museum of the City of New York)

Riis’s photographs and those by his associates documented this terror. One of his more iconic images, Lodgers in a Crowded Bayard Street Tenement—“Five Cents a Spot” (1889), embodied the tactics of the midnight raid.

The image documents residents rudely awakened in the dead of night. Four sets of beds are pictured in the frame, with an untold number of occupants crammed into a small room. The “raiding party” awakens five of the occupants, who look at the camera with a mixture of surprise, distrust, and anger. All told, the image is combative and undermines the individual identity of those pictured. Riis “shoots” his subjects without their permission; to him, the people in the room are simply statistics, part of the fabric of the tenement problem.

Riis’s camera was not just aimed at the residents of the room. It was aimed at the walls, the condition of the building, and the landlord who profited from overcrowding. Riis, who at this time had moved his family to the suburbs, detested unclean environments. He later wrote, “I hate darkness and dirt anywhere, and naturally want to let in the light.”5

Jacob A. Riis, A Typical East Side Block, halftone reproduction from The Battle with the Slum (New York, 1902)

To Riis, reform of the tenements meant literally cleaning up the neighborhood. He believed that a clean, ordered environment would produce good citizens with good morals.6 Yet, Riis often contradicted himself on where to assign blame for the conditions of the tenements. At times, he blamed the physical environment of the tenements for trapping its residents into cycles of poverty and crime. Other times he blamed the wealthy for being greedy, exploiting the poor, or having a callous indifference to their plight. Riis also blamed the residents for the condition of their neighborhood and the choices that they made. He argued that individuals with poor character (and other times specific ethnic groups) were predisposed to live in and to remain in the tenements.7

Speaking for Others, Speaking to the Wealthy

If Riis was consistent in any respect, it was that he regularly insulted the people he sought to help. His signature text, How the Other Half Lives, set the bar for insensitivity. Riis consistently criticized immigrant communities for not assimilating fast enough into American culture and painted all people within an ethnic group with the same broad strokes. Riis described Russian and Polish Jews as those who “carry their slums with them wherever they go, if allowed to do it.”8 He ridiculed Jews as thrifty and blamed the plight of Bohemian immigrants on their landlord/employer—“almost always a Jew.”9 Italians garnered slightly more respect: “In the slums he is welcomed as a tenant who ‘makes less trouble’ than the contentious Irishman or the order-loving German, that is to say: is content to live in a pig-sty and submits to the robbery at the hands of the rent-collector without murmur.”10 Riis portrayed Chinese men as impossible to assimilate. To Riis they were opium addicts and individuals who would “rather gamble than eat any day.”11

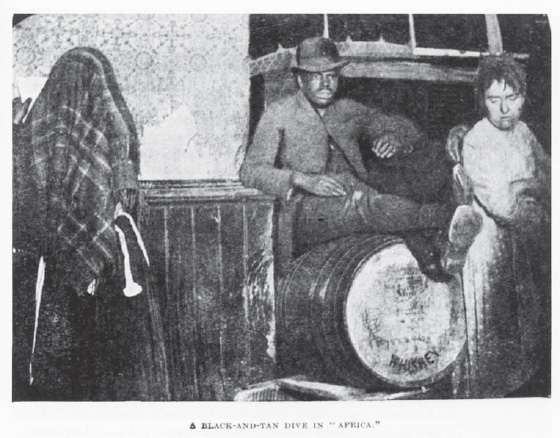

He added, “There is nothing strong about him, except his passions when aroused.”12 His opinions of African Americans were slightly more sympathetic, yet equally racist. He blamed both slavery and the individual for his negative appraisal. “With all his ludicrous incongruities, his sensuality and his lack of moral accountability, his superstition and other faults that are the effect of temperament and of centuries of slavery, he has his eminently good points. He is loyal to the backbone, proud of being an American and of his new-found citizenship. He is at least as easily moulded for good as for evil.”13

Jacob A. Riis, Richard Hoe Lawrence, and Dr. Henry G. Piffard, Black and Tan Dive, ca. 1887–1888, halftone reproduction from How the Other Half Lives (New York, 1890)

Between the lines and the overt racism, Riis leveled his harshest critique on groups that resisted assimilation. He wished for the tenement communities to be less foreign and more “American.” He blamed both the slums and the ethnic background of its inhabitants for stalling this process. Ironically, he had a relatively progressive view of immigration policy.14 Regarding the Chinese, he wrote:

The Chinese are in no sense a desirable element of the population, that they serve no useful purpose here, whatever they may have done elsewhere in other days, yet to this it is a sufficient answer that they are here, and that, having let them in, we must make the best of it. . . . Rather than banish the Chinaman, I would have the door opened wider—for his wife; make it a condition of his coming or staying that he bring his wife with him. Then, at least, he might not be what he now is and remains, a homeless stranger among us.15

Jacob A. Riis, Mountain Eagle and His Family of Iroquois Indians—One of the Few Indian Families in the City, Found at No. 6 Beach Street, December 1895, 1895 (Museum of the City of New York)

In short, Riis was arguing for improving urban conditions that encouraged assimilation, while at the same time maintaining racial hierarchies.

This point was made clear by his text, but his photographs, seen alone, and not paired with his words, had the ability to communicate a different message: they inspire a sympathetic reaction—one that called upon his audience to lend assistance, and one where his racist messages were more diluted. Scholar Cindy Weinstein writes, “One is almost tempted to say that when his racism is in check, he finds the environment responsible for the ills of the tenants; when unchecked, the blame is placed squarely on the racial group.”16 This rings true for a photograph that Riis took of four Native Americans living in a well-kept apartment. Riis documents a family busy at work producing Native crafts while a young man plays the violin. In this image the tenements are pictured as livable.

The room is clean and the sunlight comes through the window. Here, Riis champions cleanliness and order as a solution to the tenement problem and downplays the faults that he sees in various ethnic groups.

Jacob A. Riis, Bohemian Cigarmakers at Work in Their Tenement, halftone reproduction from How the Other Half Lives (New York, 1890)

Why did Riis frame his activism and his reform efforts around issues of race and racism? The answer could be found in his audience and the expectations that he had of them. Bill Hug argues that Riis’s rhetoric was strategic.17 That his well-do-do, Protestant, white, “American” audience would not be receptive to his message of compassion and charity if he presented the tenement population as their equals. Hug writes, “To publicize the predicament of the nation’s newcomers, he would first have to appeal to his audience’s assumptions about them, or appear to—then he might subvert those assumptions. Such a strategy would amount to an ironic reversal of the hypocrisy of those professed Christians who preached compassion but practiced complacency, especially in regard to poverty and suffering in the tenements of their own city.”18

![]()

Starting in 1888, Riis lectured extensively in and around New York City and the Northeast. His mode of communication was lantern-slide lectures, which he gave to audiences of Protestant reform societies, church groups, civic improvement associations, and upper-class social clubs. Riis’s two-hour lecture revolved around projecting one hundred slides—positive images printed on glass and projected onto a wall by means of a projector, either by a magic lantern or a stereopticon—accompanied by his own narration.

Riis, despite his privileged Nordic status, had experienced what it was like to be an outsider. He knew that as a recent immigrant himself (arriving in 1870 from Denmark at age twenty-one), he was not fully accepted in the eyes of his middle-class audience; early reviews of his lecture complained that his “German” accent made him difficult to understand. Riis consistently attempted to prove how he had assimilated, how he had become an “American.” He urged his privileged audience to become active in the tenement-reform movement and asserted that helping the less fortunate would not alter their class position. His goal was to inspire his audience to care and to act. And once Riis had convinced his audience that immigrant enclaves in the tenements were inferior, he, in the words of Edward T. O’Donnell, “demolished those ideas with emotive, humanitarian photographs.”19 In essence, he appealed to his audience’s deeper conscience and asserted that the powerful class had a moral duty to act against poverty.

Riis’s slide lectures had a strong emotional effect, and audience members were purported to have cried, fainted, and talked back to the screen. But the lectures also acted as a visual tour guide of locations that the vast majority of his audience had never visited before. Many had likely traversed the Lower East Side’s streets, but never gone into the crowded apartments, the sweatshops, the family cottage industries inside homes, the basement taverns, or the police lodges that housed the homeless.

Riis also took powerful people on actual tours of the slums. He befriended Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt (a position he held before becoming the governor of New York and ultimately president) and took him on midnight tours of crowded tenement buildings and other locations where poverty and vice were rampant. At one point he provided Roosevelt with a list of the sixteen worst slum areas of the city and by 1897, Roosevelt acted on this information and ordered many of the sites to be razed.20 Riis also told Roosevelt about his own traumatic experiences staying in police lodging houses when he first arrived in the United States in 1870, an incident where the police kicked him out of the lodge and killed his newly adopted dog in front of him. This retelling of a brutal story, along with the guided tour, convinced Roosevelt to permanently close down the police lodges in favor of more sanitary and humane night shelters that were run by the city.

Riis’s appeal to Roosevelt and others was, ultimately, tactical. His goal was to push his audience—wealthy people—to act. His writings and photographs served as a warning: reform the tenement neighborhoods, or the anger from the residents of these neighborhoods will be directed at the audience.

John Gelert, Police Monument, 1889 (Chicago History Museum)