Haymarket: An Embattled History of Static Monuments and Public Interventions

On MAY 4, 1927, a Chicago streetcar driver rumbled down Randolph Street. The driver had routinely passed by the Police Monument, the daunting statue of a policeman that commemorated the 1886 Haymarket Riot solely from the perspective of the police. The monument had originally stood in Haymarket Square, the site of the riot, but due to congested traffic, the city moved it to Union Park, between Randolph and Ogden. Its new location did not calm the discontent that much of the city, with a strong working-class identity, felt toward the statue. It had been vandalized before, but this anger was about to be taken to a new level. Veering from his normal route, the driver suddenly jumped the tracks and directed his streetcar full speed ahead into the base of the monument, knocking the statue to the ground. The driver, whose name is only referenced in historical accounts as O’Neil, gave a simple reason: he was sick of seeing that policeman with his arm raised.1

In 1927, the memory of Haymarket still registered with much of the U.S. public, yet as the decades passed, it had begun to fade, even within Chicago. The distance of time, the failure of schools to teach its history, and a concerted effort by the city of Chicago and the federal government to erase its presence from public space all added to the steady disappearance of the memory, with consequences for future generations—primarily keeping the public uninformed about its own labor history.

Haymarket as Unresolved History

The events at Haymarket in 1886 grew out of the international eight-hour workday movement. On May 1, Chicago was just one of many cities that participated in a national strike for the eight-hour day. The Chicago protest was massive and drew more than 80,000 marchers in a parade up Michigan Avenue. At the same time, solidarity strikes were occurring throughout the city. At the McCormick Harvester Works, on the city’s South Side, trouble broke out during a skirmish between striking workers and replacement scabs. Some 1,400 workers had been on strike since mid-February, and tensions were running high against the three hundred strikebreakers who had crossed picket lines. On May 3, two hundred police were called in. The police opened fire on the strikers, killing four and wounding many others. August Spies, one of the prominent anarchist leaders in the city, had been addressing strikers at another plant just down the road when the massacre took place. Outraged, he rushed to the printers and issued a flyer that began with the inflammatory headline, REVENGE! WORKINGMEN, TO ARMS!!! A second flyer called for a protest demonstration the next day (May 4) at Haymarket Square.

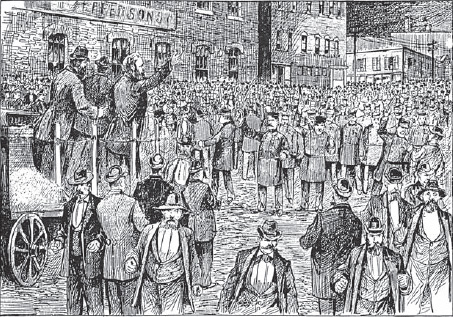

At Haymarket Square on May 4, Spies spoke to a crowd of 3,000, as did Albert Parsons, the editor of the largest anarchist newspaper in the country, The Alarm: A Socialist Weekly. Chicago was the epicenter of the anarchist movement in the United States, a highly organized radical movement whose most prominent leaders addressed massive labor rallies and agitated on behalf of many of the poor, the unemployed, and immigrants within the city. At Haymarket Square, Spies, Parsons, and others denounced the police violence of the day before. Mayor Carter Harrison showed up at the demonstration and reported to the police that the event was orderly and headed home for the evening. By ten p.m., two-thirds of the crowd had left, and rain began to fall.

Unknown artist, the arrival of the police at the Haymarket Meeting (Lucy Parsons, Life of Albert R. Parsons, Chicago, 1889)

The event likely would have wound down without incident had the police not opted for a show of force. One hundred and eighty officers marched toward the crowd demanding that it disperse. Someone, whose identity remains unknown to this day, threw a bomb into the crowd of charging policemen. Was it thrown by a worker seeking revenge for the police violence from the day before? Was it an agent provocateur willing to use violence to disrupt the gains made by the labor movement? More than 125 years later, no one can say for certain.2 However, we do know that following the mayhem of the blast, police fired at will, killing many, including fellow officers. At least eight policemen died from the explosion and the spray of bullets, more than two hundred civilians were injured, and there was an uncounted number of deaths.

The ramifications of the blast would be profound. The police seized on the event to attack organized labor by shutting down labor newspapers and arresting hundreds of individuals, essentially crushing the anarchist movement within Chicago. Eventually, eight anarchists (the majority of whom were German immigrants) were brought to trial, including some who were not even present at the demonstration. On November 11, 1887, a date that became known as Black Friday, the defendants were found guilty. August Spies, Albert Parsons, and two others—Adolph Fischer and George Engel—were sentenced to death after a grossly unjust trial. Another man sentenced to die, Louis Lingg, committed suicide in jail, and three others—Michael Schwab, Samuel Fielden, and Oscar Neebe—received prison sentences. In the aftermath, the men who were executed became martyrs to labor movements throughout the world, their memory kept alive by images, poems, and songs. Yet in Chicago, the battle over the martyrs’ memory, particularly over the building of monuments that referenced Haymarket, would be bitterly contested.

Taking Sides: The Police Monument and the Haymarket Monument

Since 1886, organized labor, anarchists, and the police have clashed over opposing visions about how the Haymarket tragedy should be remembered. Unions and labor historians have largely come to view Haymarket as part of the overall struggle for the eight-hour day and workers’ rights, and have distanced themselves from the radical anarchist principles that the martyrs had called for in the late 1800s. Spies, Parsons, and others had agitated for a collective society to replace capitalism and private property; they viewed the U.S. government as a hostile entity that perpetuated a society based on inequality and a class system. Their call for a radical restructuring of society ran counter to the goals of the modern labor movement, which generally lobbies for higher wages, better working conditions, and other policies that benefit unionized workers.

The labor movement has long argued that an official monument should exist at Hay-market to represent the history and concerns of workers from a vast range of professions and political viewpoints. Many anarchists, however, have argued that the martyrs who died for their convictions would abhor any type of official monument that was sanctioned by the government.

The police, in yet another view, insist that Haymarket be remembered simply as the event where an anarchist-led labor movement murdered their fellow officers. In their estimation, if a monument should exist, it should honor the police officers who died. For more than a hundred years, the police viewpoint held sway in Chicago. Haymarket Square either featured a monument to the police or it remained bare, without any notice of what had transpired there. Labor and anarchists were barred from placing a monument representing their perspectives on the riot anywhere within city limits.

Anarchists responded to this ban by erecting a monument in 1893 in the nearby suburb of Waldheim (now Forest Park) at the gravesite of the executed martyrs at Waldheim Cemetery. The Pioneer Aid and Support Association, an anarchist group that provided aid for the widows and the children of those executed and jailed following the Haymarket trial, organized the monument campaign. Albert Weinert was selected to sculpt the Haymarket Monument, and in his design, he depicted an allegorical figure of Justice placing a laurel wreath over the head of a dying worker.

Martyrs’ Monument at Waldheim, ca, 2006 (photograph courtesy of the author)

The female figure of Justice (also interpreted as Liberty, Anarchy, or Revolution) looks into the distance with an intense gaze, and is portrayed as a protector of working-class people.

This powerful monument would quickly become a focal point for the ceremonies of working-class people and radical movements, starting with its dedication on June 25, 1893. The date coincided with the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, which allowed thousands of visitors who were in town from around the world to attend the monument’s unveiling. James Green explains the importance of the ceremony, along with the city’s effort to neutralize its effect:

The martyrs’ families and supporters ritualized the act of remembering and began to do so immediately with a funeral many witnesses would never forget. After struggling with city officials who prohibited red flags and banned revolutionary songs, the anarchists led a large parade silently through Chicago’s working-class neighborhoods on the long walk to Chicago’s Waldheim Cemetery . . .3

More than 3,000 people marched in the parade, and 8,000 were present at the cemetery during the dedication. On the base of the monument were chiseled Albert Parsons’s final words before he was hanged: “The day will come when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you are throttling today.”

The day after the ceremony, Gov. John Peter Altgeld pardoned the three men who remained in jail. He knew this action would ruin his political career, but Altgeld stood by his convictions, stating that the trial was a travesty of justice. His pardon would later be inscribed on the back of the monument. For his action, he was scorned by the power structure and celebrated by labor, who tried in vain to have a monument built to him at Haymarket Square. But as with the martyrs’ monument, the city of Chicago would refuse.

In the years to come, the Haymarket Monument at the Waldheim Cemetery would continue to serve as a symbol of resistance for the labor movement. The monument has often been the site for May Day celebrations and remembrance of May 4 and November 11. The cemetery also would become the resting place of many of the country’s most radical labor leaders and revolutionaries, including Emma Goldman, Lucy Parsons, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Joe Hill, Big Bill Haywood, and many others who were buried there or had their ashes spread in the cemetery.

In comparison, the Police Monument, sculpted by Johannes Gelert, was dedicated in 1889, three years before the Haymarket Monument. It also had annual remembrance celebrations and was cherished by those it best represented—the police. The Chicago Tribune and the Union League Club of Chicago had organized the fund-raising drive for the monument, which was to be placed in the center of Haymarket Square—a working-class section of town, home to farmers’ markets and numerous union halls.4

The placement of the monument of a police officer with his hand raised in a “halt” pose was an overt message to the people of Chicago that if they rebelled and went on strike, there would be consequences. Thus, it was no wonder that the Police Monument received little fanfare from working people—the majority of the population of Chicago. After the Police Monument was first toppled in 1927, it was moved away from the streetcar lanes so renegade drivers could not destroy it so easily. Eventually, it was moved to Jackson Boulevard, where it was ironically placed facing a statue of Mayor Carter Harrison, who had once testified against police corruption.5 The two figures stared at each other, engaged in a silent dialogue.

In 1956, the Police Monument was moved once again, and returned to the Haymarket area, two hundred feet west of its original location. The Chicago Police Department had lobbied for the monument to be moved back to Haymarket Square, but by the 1950s, a new disruptive force—the construction of the Kennedy Expressway—had carved up the downtown neighborhood, erasing many landmarks from the original site.

![Haymarket Square, ca 1893, photogravure (LC-USZ62-134212, [b&w film copy neg.], LC-USZ62-29792 [b&w film copy neg.], Library of Congress)](images/f0075-01.jpg)

Haymarket Square, ca 1893, photogravure (LC-USZ62-134212, [b&w film copy neg.], LC-USZ62-29792 [b&w film copy neg.], Library of Congress)

Set among high-rise buildings, the monument rested on a special platform overlooking the freeway, on the north side of Randolph Street a block west of Desplaines. On May 5, 1965, the city council designated the monument a historical landmark, but this designation meant little to those set to start a new wave of attacks. The Police Monument soon fell prey to 1960s radicalism.

May 17, 1963, Ceremony at the Police Monument at Randolph Street and Kennedy Expressway (Chicago History Museum)

On October 6, 1969, the Weathermen, a radical, underground splinter of SDS (Students for a Democratic Society), stuck dynamite between the monument’s legs and blew it up, sending the legs of the statue flying onto the freeway below.

Although the Weathermen had yet to make a statement, Sgt. Richard Barrett, president of the Chicago Police Sergeants Association, directed the blame toward SDS. In a statement (which was later retracted by his superintendent) Sergeant Barrett stated:

The blowing up of the only police monument in the United States by the anarchists . . . is an obvious declaration of war between the police and the S.D.S. and other anarchist groups. We feel that it is kill or be killed regardless of the Jay Millers [director of the Illinois ACLU], Daniel Walkers [author of a federal report that blamed the police for the rioting during the Democratic National Convention], and the so-called civil rights acts.6

In the midst of this mounting tension between the police and anarchists, Mayor Richard J. Daley ordered that the monument be rebuilt. In his statements to the press, he asked for private donors to help with the costs and eventually received funds from many, including the International Brotherhood of Teamsters and a number of other unions. On May 4, 1970, the statue was rededicated on the anniversary date of the Haymarket Riot. At the dedication ceremony, Daley told the crowd:

This is the only statue of a policeman in the world. The policeman is not perfect, but he is as fine as individual as any other citizen. Let the younger generation know that the policeman is their friend, and to those who want to take law into their own hands, let them know that we won’t tolerate it.7

The Weathermen apparently ignored Daley’s threat because on October 6, 1970, exactly one year after they first demolished the monument, they blew it up again. This time, shortly after the blast, the press received a call from a Weatherman stating, “We destroyed the Haymarket Square Statue for the second year in a row in honor of our brothers and sisters in the New York Prisons. . . .”8

In what was clearly becoming a battle of sheer will and determination between the two sides, Daley ordered round-the-clock police security to protect the statue—at a $67,440 annual cost. The media ridiculed the twenty-four-hour guard, noting that there were more important matters for the police to attend to. This dilemma generated a series of imaginative and humorous ideas for how to protect the beleaguered monument, which included placing a large plastic dome over it, or casting a series of disposable fiberglass police statues, which could be easily replaced.9

Realizing that the monument would continue to be attacked as long as it remained in Haymarket Square, the city moved the Police Monument in February of 1972 to a new location—inside the lobby of Central Police Headquarters on Eleventh and State Street, where it was completely removed from public sight and a visitor’s pass was required to view it. This location also proved to be temporary, and in 1976 it was moved again and placed within the exterior courtyard of the Police Academy at 1300 West Jackson. However, the massive concrete base for the monument remained at Randolph Street for two more decades, a visual reminder of how contested the space had been and continued to be.

The Temporary Monument: Public Interventions 1972–2004

“I really don’t trust monuments.”

—Michael Piazza, organizer of the “Haymarket 8-Hour Action Series”10

The lack of a monument at Haymarket from 1972 to 2004 did not mean that the site was any less contested or active. For some, the empty site presented an opening to cast one’s own perspective within public space. A monument, by its nature, is already defined, static, and rarely allows for participation.11 A monument may allow for critique, for the viewer to respond to it, but it does not allow one to take an active role in adding to the dialogue and inserting one’s voice into the landscape, unless of course one does something drastic. In this manner, monuments often define a singular point of view that shuts out other perspectives. The lack of a statue at Haymarket, however, allowed for multiple perspectives through the creation of ephemeral monuments—temporary actions, performances, and other types of decentralized public interventions—that many individuals and groups have undertaken to put forward different “unofficial” versions of the Haymarket history into the physical space and the collective memory. These actions, lacking any type of permission or government role, were in many respects much more closely aligned with the ideals of the Haymarket martyrs.

One such action took place in 1996, just before the Democratic National Convention that was being held in Chicago. Kehben Grifter (who works with the Beehive Design Collective) and Evan Glassman created a small, hand-cut stone mosaic to the anarchist martyrs and installed it within the sidewalk at the Haymarket site without attempting to go through any official channels to obtain permission.12 At the time, both were working nearby the Haymarket site and noticed that the sidewalks were being redone and that wet cement was in the process of drying, creating the perfect opportunity to install the mosaic. However, when they went to place the piece, they were spotted by city workers and were questioned. They quickly talked their way out of trouble by citing names in the city bureaucracy and falsely stating that the project had been given city approval. To verify their claims, the workers called their superior and described the mosaic and its content. To the artists’ luck, the city official did not comprehend the illicit nature of the project, and neither did he understand the mosaic’s message or the significance of the Haymarket site. Better yet, the official insisted that the workers on site install the mosaic for them! For five weeks it remained at the Haymarket site and would likely have lasted longer had not a Chicago Tribune article brought attention to the mosaic, prompting the city to remove it.

Remember the Haymarket Anarchists, hand-cut stone mosaic installed at the Haymarket site, 1996 (Kehben Grifter)

The pedestal of the Police Monument was also removed in 1996, just before the Democratic National Convention. The city must have finally realized how inviting the site was and likely feared that a large demonstration would take place there. To many, the removal of the pedestal was a great loss, for it represented just how contested the history of the Police Monument had been, and it had served as a grand stage for performances and other public interventions. However, when the cement slab was removed, it left a giant circle, eighteen feet in diameter, clearly marking where it once stood. Artists quickly realized that the circle was an ideal stage.

John Pitman Weber’s reenactment of a Eugene Debs speech, part of the Haymarket Eight-Hour Action Series, 2002 (Michael Piazza)

Michael Piazza, a Chicago artist, employed the circle for the “Haymarket Eight-Hour Action Series” that he initiated in 2002. Piazza was inspired to launch the series after seeing the Chicago printmaker Rene Arceo perform on the circle during a May Day celebration. Arceo’s performance was simple but poignant. He pulled up in a car, then ran up and started stomping on the circle as a crowd watched. Piazza’s tribute to the “Arceo Stomp” was to put out a call inviting other artists to do separate eight-hour actions at the site. Piazza notes that:

Ever since 1986, I had been monitoring this blank pedestal and I realized that there was a division between a small group of people in town who knew what it represented, who had this local knowledge and memory, while there was a whole other group who just thought it was an empty pedestal. That always fascinated me.13

Piazza reasoned that artists, with their talents and creativity, could reclaim this history and make it more visible. Yet after Piazza surveyed the site and measured the diameter of the circle, the city, either intentionally or coincidentally, paved it over, leaving no physical evidence of where the Police Monument had once stood. Undeterred, the first project of the Eight-Hour Action Series, involving Javier Lara and students from the School of the Art Institute, held a sewing bee at the site and constructed a large orange circle that became a visual reminder of the monument’s existence. In other performances, the new circle served as a stage for a number of soapbox presentations, including William Adelman’s historical presentation on Haymarket and John Pitman Weber’s reenactment of a Eugene Debs speech.

Other performances that were part of Piazza’s Eight-Hour Action Series used the circle as an end point. Larry Bogad did a project entitled The Police Statue Returns for which he created a giant puppet that resembled the original police statue. Bogad paraded the puppet along from the Daley Center, through downtown and eventually ending on Randolph Street. At the former location of the Police Monument, a large anarchist flag was placed over the circle in an act of reclamation.

Lauren Cumbia, Dara Greenwald, and Blithe Riley, Hay! Market Research Group, part of the Haymarket Eight-Hour Action Series, 2002 (Michael Piazza)

Another Eight-Hour Action Series project that spoke of the changing dynamics within Chicago was Hay! Market Research Group, a collaborative action by Lauren Cumbia, Dara Greenwald, and Blithe Riley. The group set up a table and a sign on Randolph Street at the location of the former Police Monument. The sign acted as a visual component, similar to a billboard, which first caught people’s attention. Various slogans on the sign were interchanged, including: “What Happened Here in 1886?”; “Guilt by Association: Who Died for Your Eight-Hour Workday?”; ” 4 Hung, 1 Suicide, 3 Pardons”; and “Public Hanging, Lethal Injection, Indifference?” Once people walked up to the information table, they could fill out surveys on Haymarket and issues that were connected to the present.

Javier Lara and students from the School of the Art Institute hold a sewing bee and create a large orange circle that marks the former location of the former Police Monument, part of the Haymarket Eight-Hour Action Series, 2002 (Michael Piazza)

In nearly every intervention, the artists involved were responding to far more than just the Haymarket history. These actions responded to the entire city landscape and the culture at large. For some of these performances, Haymarket was simply a starting point. Brian Dortmund’s project for the Eight-Hour Action Series was a May Day bike ride that traveled from Haymarket to the Waldheim Cemetery. In subsequent years, Dortmund has continued to do the ride, but changes the route, so that the riders travel to different locations in the Chicago vicinity that are specific to labor and other radical struggles. In this manner, those who participated in the action formed a community, learned about various histories, engaged in dialogue, and had a shared experience.

The works in the Eight-Hour Action Series, as compelling and creative as they are, come with built-in limitations. Any action that is seen by such a small number of people has the potential to be easily forgotten and its effect may be minimal in creating widespread change. Mary Brogger’s monument at Haymarket, installed in 2004, allows us to compare these two divergent approaches.

Mary Brogger’s Haymarket Monument: The Monument That Forgot Class Struggle

“I think we’re showing a new way to do monuments at historic sites. You make them open rather than pressing a precise meaning on people or directing them toward a specific feeling or reaction”

—Nathan Mason, special projects curator of Chicago’s Public Art Program14

Nathan Mason’s quote accurately describes the scope and the vision of the new monument, sculpted by Mary Brogger, that now resides on Desplaines Street. The historic location, which had been empty for so long, now features an abstract monument of bronze, genderless figures colored in a red patina, constructing and deconstructing a wagon. At the base of the monument, a series of cautiously worded plaques explains the history of Haymarket. Its mere existence—a monument to Haymarket within a city that had long since refused to acknowledge the history except from the perspective of the police—is startling and leads us to wonder, Why now?

To better understand how this drastic change came to be, it is important to first examine the complicated decade-long process that led up to Mary Brogger’s public artwork that was funded and approved by the city. When talking about the new monument’s content, it is all too easy to focus attention on Mary Brogger, the sculptor herself. But it was the coalition of government agencies, labor organizations, and historians that first agreed upon a series of parameters that ultimately led to the monument’s realization and the content that it would project. A key player in this process was the Illinois Labor History Society.

The ILHS had lobbied the city government for a permanent monument at the Haymarket site since the organization’s founding in 1969. Despite the fact that the city and the police had created a formidable obstacle to any type of monument to Haymarket from the perspective of labor or anarchism, there were some in Chicago who were willing to challenge this blockade. Les Orear, a Packinghouse Union activist, and William Adelman, a labor historian, decided to pool their resources and energy to form the Haymarket Workers Memorial Committee. This project soon became part of a larger vision, and on August 5, 1969, the Illinois Labor History Society was formed. The ILHS, along with other local activists, including Bill Garvey, an editor of the newspaper Steel Labor, began the long process of lobbying the city government for a monument at Haymarket that represented the position of labor. One of the first steps toward revitalizing interest in a potential monument was a public performance in 1969 at the site where the bomb had exploded in 1886. Studs Terkel stood on top of a makeshift wagon and spoke of Haymarket’s history. Terkel’s performance, a public intervention in its own right, would foreshadow the many future actions that would take place in ensuing decades as others reclaimed the space’s history by means of temporary installationsa ndp erformances.

Mary Brogger, Haymarket Monument on Desplaines Street, Chicago, ca. 2006 (photograph courtesy of the author)

Around the same time, the ILHS began organizing events at Waldheim Cemetery for people to meet and listen to speeches in front of the Haymarket Monument on significant dates that corresponded to Haymarket’s history. The ILHS role of promoting Haymarket’s labor history became even more “official” in 1973, when the deed for the Haymarket Monument at Waldheim was transferred to the ILHS from the last surviving member of the Pioneer Aid and Support Association, Irving S. Abrams. The ILHS assumed the role of its owner and became responsible for the monument’s upkeep and annual commemorations.15 Yet as Lara Kelland notes, this was not without opposition:

Anarchists have responded in kind. . . . A small group often appears at Waldheim during the ILHS events, jeering and interacting with the monument in an attempt to disrupt the proceedings in protest of the ILHS ceremonial work.16

Despite these constant jeers from anarchists, the ILHS made inroads in lobbying the City of Chicago to also have a monument to Haymarket commissioned at the original Haymarket site. This goal likely would have been reached had it not been for the untimely death in 1987 of Mayor Harold Washington, one of the rare high-profile politicians who advocated for the public recognition of Chicago’s labor history.17

However, in 1998, the ILHS, which had teamed up with the Chicago Federation of Labor, found an unlikely audience in Mayor Richard M. Daley’s administration. Daley (the son of Richard J. Daley, who had been mayor from 1955 to 1976) gave the go-ahead to listen to various proposals for a monument, and a coalition developed that would include representatives from the Chicago Historical Society and the Chicago Police Department. And rather than focusing attention on the anarchist martyrs, the police, the explosion of the bomb, or the subsequent trial, the group settled on the broad-based theme of a speaker’s wagon representing “free speech.” The wagon alluded to the place where Samuel Fielden had addressed the crowd on May 4, 1886, just before the bomb exploded, but the concept of free speech is much more elusive and abstract. Don Turner, who at the time was the president of the Chicago Federation of Labor, notes the significance of this choice for the proposal’s eventual approval:

I think the key issue was removing the focus from the anarchists and making it a First Amendment issue—though it’s not unlike we still don’t have anarchists.18

Turner further explained: “We brought everybody into the process—the police, the labor community, historians—and we came up with this idea of the wagon as the symbol of freedom of speech. That’s how we really put our arms around it.”19 Everybody, that is, except the anarchists whose political forebears were at the heart of Haymarket’s historical significance.

In 2000, with the concept established, funding was secured from a state program, Illinois FIRST, which designated $300,000 toward the project. By 2002, the project was under the jurisdiction of the “Haymarket Tragedy Commemoration of Free Speech and Assembly Monument,” directed by Nathan Mason, the special projects curator for Chicago’s Public Art Program. With the funding and theme in place, the next step was to select an artist to sculpt the vision that the committee had already established. Ten artists were selected to submit proposals, and an eight-member project advisory committee composed of representatives from labor, the police, historians, and community members chose the local sculptor Mary Brogger.20

Despite the fact that this was Brogger’s first figurative public commission, her Haymarket Monument satisfied the conditions of the committee’s vision of a nonconfrontational monument focused on the speaker’s wagon and free speech. Brogger states:

I was pretty adamant in my own mind that it would not be useful to depict violence. The violence didn’t seem important, because this event was made up of much bigger ideas than one particular incident. I didn’t want to make the imagery conclusive. I want to suggest the complexity of truth, but also people’s responsibility for their actions and for the effect of their actions.21

She further explained the symbolism and the message of the monument:

It has a duality to it. From the standpoint of the wagon being constructed, you see workers in the lower part are working cooperatively to build a platform from which the figures on top can express themselves. And for the viewpoint of the wagon being dismantled, you see [how] the weight of the words being expressed might be the cause of the undoing of the wagon. It’s a cautionary tale that you are responsible for the words you say.22

Brogger’s comments are as ambiguous as the monument itself; they could be understood to say that the anarchist labor activists had it coming to them for directly challenging the power structure. Although Brogger clearly seems more troubled by the speech of the anarchists than the indiscriminate gunfire of the police, a focus on the artist is not helpful here. Brogger was a minor player in the ongoing debate over the new monument. In the majority of public art projects today, the artist is simply hired to carry out the subject matter and the content that someone else has already determined. The artist can add an aesthetic quality to the work, and only in this regard can we critique Brogger’s efforts. Michael Piazza’s humorous commentary describes her sculpture as a “Gumby version of a romantic Civil War memorial” but that aside, the real issue raised by her Haymarket Monument is the nature of public art itself and the pitfalls of allowing a small group of individuals to decide what is placed within civic spaces.23

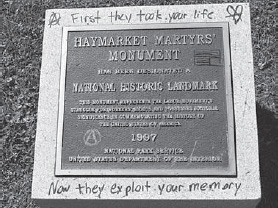

Graffiti on the plaque noting the National Historic Landmark status of the Martyrs’ Monument at Waldheim, 1997 (Bogdan Markiewicz)

The small committee of government agencies, historical societies, and labor organizations (the ILHS, the Chicago Federation of Labor, the Chicago Historical Society, and the Chicago Police Department) that agreed upon the monument’s content was not a broad cross-section of the population. Instead, the process-by-committee was guarded and exclusive. For example, only ten artists were invited to submit proposals for the design. However, the bigger issue was the exclusion of voices that might have differed with the committee’s opinions. From the start, anarchists were shut out of the discussion. Nathan Mason, Chicago’s Public Art Program curator for the project, remarked in early 2004, “Who would they choose to represent themselves?”24 His dismissive comment indicates a lack of serious effort on the committee’s part to solicit the input of anarchists and also assumes that the committee itself was more qualified to visualize Haymarket’s history. The committee, with little effort, could have reached out to anarchists within Chicago and beyond. It didn’t.

On September 14, 2004, the new monument was dedicated. Not surprisingly, the public reaction to the dedication was deeply divided.25 During the official dedication ceremony, city officials, representatives of organized labor, and police officers were self-congratulatory with one another. A central theme of many of their speeches was reconciliation, the notion that the wounds of the past and the divisions between labor and the police were beginning to heal. A small group of anarchists in the crowd held up black flags to voice their disgust with the entire proceedings. Anthony Rayson was quoted in the Chicago Sun-Times as saying, “This is a revisionist history thing. They’re trying to whitewash the whole thing, take it away from the anarchists and make it a free-speech issue.”26 A New York Times article quoted another dissenting voice in the crowd, Steve Craig:

Those men who were hanged are being presented as social democrats or liberal reformers, when in fact they dedicated their whole lives to anarchy and social revolution. If they were here today, they’d be denouncing this project and everyone involved in it.27

Those present also heard Mark Donahue, president of the Chicago Fraternal Order of Police and a member of the monument’s project advisory board, state, “We’ve come such a long way to be included in this. . . . We’re part of the labor movement now, too, and glad to be there.”28 The question remains, however, would Donahue have said this had the monument given a more pronounced focus to either the anarchist martyrs or the class conflict between labor and the police that had resulted in the Haymarket riot?29 Moreover, Donahue’s notion of the police as having now become part of the labor movement is also duplicitous. While it is true that police officers are “workers” and are unionized, his comments promote the notion that the police and other workers in society share the same interests and class goals. Today, the police still protect the interests of capital and the state. At labor demonstrations, their batons and pepper spray fall squarely upon the heads of workers. Perhaps Donahue’s biggest error was that he attempted to speak for a larger entity, when in fact he was speaking solely as an individual. Diana Berek, a Chicago-based artist and coeditor of Chicago Labor and Arts Notes, explains, “Individuals can reconcile their wounds, but not classes, not institutions, and certainly not the entities of organized labor and the police.”30

If anything, Donahue’s statements reinforce just how easy it is to oversimplify and blur history, especially events as complex as Haymarket. The new monument only adds to this confusion, and the attempt to make it appear objective is one of its greatest flaws, for it is not possible to be neutral on the issue of Haymarket. As Berek notes, “Battles for social justice, conflicts around economics, and political class conflict will never be easy to tidy up so that they can be objectified, sensitized, and made emotionally uplifting to every point of view.”31 While much has changed over the 120 years since Haymarket, we do not live in a society where class conflict is a thing of the past. If anything, the division between the haves and the have-nots has become increasingly pronounced, and the methods for marginalizing working-class people, unions, and social movements have become increasingly sophisticated. A monument can proclaim that Haymarket was about free speech, but that does not make it necessarily true.

Robert Edmond Jones, Paterson Pageant program cover, 1913 (American Labor Museum/Botto House National Landmark)