Blurring the Boundaries Between Art and Life

ON JUNE 7, 1913, an event occurred that completely blurred the boundaries between performance and protest. Journalist and poet John Reed led a procession of more than a thousand striking workers through the streets of Paterson, New Jersey, to board a special thirteen-car train destined for New York City. When they arrived in the city, they gathered for a rally at Union Square, followed by a march up Fifth Avenue toward Madison Square Garden, while the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) band played “La Marseillaise” and “The Internationale.”1 On top of Madison Square Garden’s tower, the IWW initials glowed in red lights. Inside, the venue was transformed into a Wobbly hall, with red IWW banners, sashes, and ribbons throughout the building. The stage included a massive two-hundred-foot painted backdrop of a large silk mill, flanked by smaller mills. Up and down the aisles, volunteers walked, selling copies of the program, The Masses, and other radical publications. When the house lights went down and the curtain opened, Reed went to work directing the massive crew of striker-actors and actresses—playing the role of themselves, reenacting their struggle—the Paterson strike during the strike itself.

Four months prior, 25,000 of their fellow workers had walked off their jobs in a strike that had crippled the Paterson silk industry. Workers had united over a number of issues that affected the lives of the ribbon weavers, broad silk weavers, and dyers. Together they protested the long hours (the ten-hour day), the three-to-four-loom system that replaced the double looms, the dangerous conditions of the dye houses, the “docking system” for female apprentices, and the different wage scales found within individual shops.2 Combined, they went on strike.

IWW leaders had been invited in as strike organizers, arriving with much fanfare following the momentum of the Lawrence textile strike in Massachusetts in 1912, in which workers had won the majority of their demands, in part due to the leadership and tactics of the IWW. In Paterson, the IWW invited another group to help them in their efforts: Greenwich Village artists. This alliance led to the creation of a pageant—a theatrical performance to re-create recent history and a production to make history—to help raise money for a strike relief fund, help publicize the strike, and help inspire the workers to continue to hold out.

Strikers march up Fifth Avenue en route to Madison Square Garden, June 7, 1913 (UPI/Bettmann Newsphotos)

Throughout the performance, the audience of 15,000 sang in unison with the cast and berated the police and the strikebreakers. On the main floor, a large central aisle led directly up to the stage, serving as a street for the cast of a thousand striking workers to march down, and was later utilized during a funeral scene. Here, the performers could stand side by side with the audience in unity, an action that further blurred boundaries: was the pageant indeed a drama, or had the strike itself been transported from Paterson to New York City? When IWW strike leaders Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Bill Haywood, and Carlo Tresca addressed the crowd of 15,000, their speeches were similar, if not identical, to those they had given in the weeks and months prior in Paterson. Were they part of the drama or was it a recruitment pitch for the strike? These questions were what made the pageant so exceptional. It was also what made it so problematic. A pageant is not a strike, and vice versa, and the stakes were extremely high. A pageant could aid the workers’ demands or it could harm them. Additionally, it could either help or harm the fragile alliance of those who came together to put on the pageant—striking workers, IWW organizers, and artists.

Wobblies, “Poets,” and Silk Workers

To understand the Paterson Pageant, one must first understand the IWW and what made the organization so unique and so critical. The IWW (nicknamed the Wobblies) was formed in 1905 in Chicago during a convention at Brand’s Hall, where more than two hundred socialists, anarchists, and labor leaders gathered, including William “Big Bill” Haywood (secretary of the Western Federation of Miners), Daniel DeLeon (leader of the Socialist Labor Party), Mother Jones (organizer for the United Mine Workers), Eugene V. Debs (socialist labor leader), and Lucy Parsons (labor organizer and widow of the Haymarket martyr Albert Parsons).

Those in attendance established a revolutionary union meant to confront the capitalist class. The opening sentence of the preamble read: “The working class and the employing class have nothing in common.” Instead of negotiating with the bosses, the IWW envisioned a new society based upon workers’ cooperatives and free of capitalism, bosses, exploitation, and racism. The IWW set out to recruit workers that the American Federation of Labor (AFL) largely ignored—the unskilled, recent immigrants, women, and workers of non-European heritage.

The three years following the IWW’s 1905 founding convention were marred by internal strife and defections that nearly spelled the demise of the organization. Eugene Debs allowed his dues to lapse. For many, a major point of division was whether the union should be affiliated with the electoral process and function as the labor arm of the Socialist Labor Party. Anarchists within the IWW opposed this direction and argued that the organization should remain outside electoral politics. Instead, anarchists advocated that the IWW organize a revolutionary movement through industrial unionism and general strikes. The 1908 convention sealed the split when the IWW sided with anarcho-syndicalism.

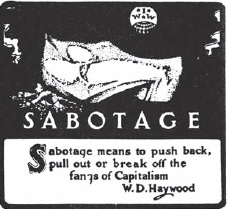

Unsigned, likely created by Ralph Chaplin, Sabotage, sticker, ca. 1910s (courtesy of Charles H. Kerr Publishers Company)

The split ensured that the IWW would not be a top-down organization and its structure would drastically differ from the majority of unions, where elected union officials held decision-making power over the rank-and-file membership. Instead, the IWW allowed for workers’ control over their own affairs, and autonomy for the many branches that were spread out throughout the country (and world) that allowed them each to respond to their unique situation, location, and work conditions. However, a common spirit still existed throughout the many branches of the organization. Irving Abrams, an IWW member who helped organize the local in Rochester, New York, described this commonality:

The priority . . . was agitation. That’s what it was. The priority was let’s bring the storm. . . . The idea was as long as you had the footloose rebel traveling from one place to another . . . you could make a big noise. That was the theory that was underlying at the time, more than anything else. It wasn’t the idea to build a labor organization as such, per se. . . . While we talked about unions, while we talked about industries, ultimately at that time, the slogan was, “Bring the revolution.”3

IWW culture helped to spread this message. The Wobbly publication The Industrial Worker wrote in 1913, “The strength of the IWW is not in its thousands of memberships—it is in its revolutionary ideas as they are translated into action against the employing class and all its institutions.”4 Revolutionary ideas were broadcast through the written word, but also through songs, poetry, soapbox speeches, theatre, graphics, cartoons, posters, slogans, and stickers—all of which became part of the IWW’s arsenal. Most significantly, IWW culture came from within. Culture was created from the bottom up. Hundreds, if not thousands, of different rank-and-file members created the culture—an approach that echoed the nonhierarchical structure of the union. Culture reflected the spirit of the Wobblies, but it also was part and parcel of IWW tactics. Culture kept a degree of unity and commonality among the many branches. It helped the IWW to maintain solidarity within, and promoted its goals far and wide to potential recruits, many of whom were migrant workers who traveled throughout the country in search of work. These migrant workers became the IWW artists, poets, and musicians.

![]()

In Paterson, the IWW entered a labor conflict where their membership numbers were not strong. Instead of organizing their own rank and file, a handful of talented IWW organizers—chief among them Elizabeth Gurley Flynn and Bill Haywood—served as tacticians and speakers to help a strike already in progress. Their role was to help with strategies and to give speeches that would keep up the workers’ spirits during the hardships of the strike. This was critical, for workers who spoke out against their employers in public and through the press faced the threat of being blacklisted. IWW speakers from out of town did not face this threat. They could be arrested, but their livelihood was not on the line.5 Eventually, 9,000 workers in Paterson signed up as card-carrying IWW members, but this should not confuse the fact that prior to the strike Paterson workers had little to no prior affiliation with the IWW.

The IWW leaders recognized this dynamic. During the strike a Central Strike Committee of two workers from each of the three hundred shops made the final decisions and ultimately led the strike. Bill Haywood stressed this point in an address to the workers at Turn Hall:

I have come to Paterson not as a leader. There are no leaders in the IWW; this is not necessary. You are the members of the union and you need no leaders. I come here to give you the benefit of my experience throughout the country.6

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn also addressed the workers. At one point she delivered more than nineteen speeches during a one-week span.7 Flynn, twenty-two years old at the time and already a veteran of labor struggles, having joined the IWW at age sixteen, helped break down the male-dominated labor movement by holding women-only meetings that encouraged women to assert their voices.

IWW leaders pause for a portrait during the Paterson Silk Strike, Paterson, New Jersey, 1913—left to right: Pat Quinlan, Carlo Tresca, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Adolph Lessig, and Big Bill Haywood (Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan)

To Flynn and the IWW, the strike represented workers taking control of their own lives—a path toward worker control of industry and society. However, not all of the Paterson silk workers shared these same aspirations. To many, the strike was about “looms, wages and hours.”8 Thus, the immediate task at hand was to win the strike, to convince the workers to stay out on the picket line, and to hope that the will of the owners of the silk industry would break first.

This was a difficult task, for the strike had hurt manufacturers’ profits, but it did not completely stop production. While the factories were shut down in Paterson, the owners continued to operate their mills in eastern Pennsylvania. As the strike wore on, workers and their families faced a dire situation: some were on the brink of starvation, and many were dependent upon relief funds for their subsistence. Other problems also existed: the strike received little national coverage, and when it did it was often from a pro-business, corporate perspective. The Paterson press and the New York papers blasted the IWW, vilifying them as outside agitators who had come from out of town and whom the workers had foolishly followed against their better judgment.

In response, the IWW and its allies in the bohemian artistic and intellectual subculture in Greenwich Village conceived of a project to counter the negative press attention around the strike: a pageant that re-created the strike for a New York audience. This production, they envisioned, could cast the struggle in a favorable light. It could also raise much-needed relief funds to sustain the strike.

Artists in Greenwich Village admired the IWW, but they did so largely from afar. They knew about the IWW from the Lawrence textile strike but they did not know them personally. This changed due to Mabel Dodge’s weekly Wednesday-night salon gatherings. Dodge, a wealthy socialite who had spent the previous decade living in Florence, Italy, hosted weekly gatherings in her Greenwich Village home that attracted artists and writers, including those from the socialist publication The Masses and Emma Goldman’s publication, Mother Earth. Wobbly strike leaders also frequented many of these gatherings. Dodge’s salons, open to all, gave artists the chance to meet the IWW leaders, including Bill Haywood, who frequented the events, and this is where the idea for a pageant developed, although it remains open to debate if Haywood or Dodge was the first to suggest it.

Elizabeth G. Flynn addressing Paterson Strikers, ca. 1913 (lpf0323, Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan)

A key recruit to the project was John Reed. At the time, Reed was a twenty-six-year-old recent Harvard graduate who had moved to Greenwich Village in 1911. There he met Haywood, who invited Reed to Paterson to meet the strikers. In short order, Reed was arrested for refusing to vacate the streets during a picket outside the mill’s gate. At his sentencing hearing, he was asked what his business was, being in Paterson. He replied, “Poet.”9

Reed’s answer did not keep him out of jail. He was given twenty days, but made bail after serving only four. During these four days, however, he received a valuable lesson in life—the reality of jail, juxtaposed with the solidarity of being part of a movement, imprisoned with more than a hundred other strikers, including Haywood and Carlo Tresca.

Reed’s experience in jail had a profound effect on him. It inspired him to commit all of his energies to the cause of the Paterson strike and to reach out to like-minded artists he knew for their assistance. His recruits included John Sloan, who designed and painted a massive backdrop for a stage set, and Robert Edmond Jones, who designed the cover for the pageant’s program. Dodge helped to raise funds to cover the steep production costs.

Reed’s task was also to direct the pageant, for which he wrote the script. Initially, he envisioned ten scenes that would tell the story of the strike from its early stages to the events leading up just prior to the pageant date. He set up shop in Paterson and rehearsed for weeks with more than a thousand workers. There, he practiced songs with them and navigated the difficult terrain of convincing the workers to re-create their own recent history. One striker, whose name was never noted in the interview, stated, “We know we can make a strike pageant because we’re strikers. We’re rehearsing every day, in the strike.”10

John Reed, ca. 1910-1915 (LC-B2-3521-4, Library of Congress)

Indeed, this became a moment that blurred all boundaries. Steve Golin explains:

So close were life and art that at times they became indistinguishable. On Sunday in Haledon [the town just north of Paterson] the performers sang to a crowd larger than any that Madison Square Garden could hold. Was this the strike or a rehearsal?11

At times, witnesses to the events could not tell. Golin writes:

During one of the last rehearsals, after strikers had filled all the roles—including the police—a New York reporter walked into Turn Hall and saw twenty big men charging a crowd of women and men and actually beating them, while the hall rang with boos. The reporter thought the police were breaking up the rehearsal and said so to a male weaver, who laughed and relied: “Police? Police nothing! They’re just rehearsing the second tableau for the Pageant—that’s all” . . . Completing the circle, a boy who was caught booing a real Paterson policeman claimed in court that he was only rehearsing for the Pageant.12

Meeting in Haledon in front of Botto house balcony, May 1913 (American Labor Museum/Botto House National Landmark)

Confusion was understandable; the rehearsal for the pageant had become part of the strike itself. The actual event in New York City would further complicate the matter.

![]()

The idea of transporting the strike to Madison Square Garden was not endorsed by all IWW leaders. Haywood had enthusiastically embraced the idea from the beginning, yet Elizabeth Gurley Flynn and Carlo Tresca were deeply skeptical of its overall benefit.13 For one, financial concerns had existed up until stage time, when doubts were cast about whether the event itself would sell out. The high cost of the production had raised the ticket costs, placing it out of the range of many working-class people, prompting the organizers to drop the cost of many of the $1 to $3 seats to a quarter.14

The price reduction guaranteed a full house but left the profit margin in doubt. Regardless, the audience of 15,000 would not be disappointed with the show. The pageant opened with the start of the strike, followed by scenes of police violence, and the funeral of a fallen worker. The third and fourth scenes included Haywood, Flynn, Tresca, and others reenacting speeches that they had given to the strikers, encouraging them to continue their hold-out. The fifth scene portrayed the evacuation of Paterson children to safe houses in New York City, and the last scene revolved around more speeches and the strikers vowing to continue their struggle.

When the pageant came to a close, it was likely that most, if not all, of the participants—performers and audience alike—were deeply moved by what they had seen. The New York press reflected this sense of optimism and largely hailed the pageant as a success. Many reviews were positive, and even the New York Times comment—that the production was meant to stimulate “mad passion against law and order”—could be construed as a compliment, an admission by the anti-IWW paper that the event had accomplished its intended goals.15

Other reviews understood that the pageant was unlike any event that had ever been witnessed before. The New York Tribune wrote, “Certainly nothing like it had been known before in the history of labor agitation . . . Lesser geniuses might have hired a hall and exhibited [a] moving picture of the Paterson Strike. Saturday night’s pageant transported the strike itself bodily to New York.”16 And the New York Evening Post wrote, “It must be judged by its effect upon the performers as well as its effect upon the audience. Has any other art form so complicated a criterion?”17

Pageant inside Madison Square Garden, June 7, 1913 (Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives and Radicalism Photograph Collection, Tamiment Library, New York University)

This review summarized the many complexities of the pageant, but in reality any press helped satisfy the IWW organizers’ goal of generating more national publicity for the strike itself. The pageant had been devised to garner more press, to make new allies, and to raise much-needed money for the relief fund—all of which might hopefully break the deadlock within the strike.

The pageant succeeded in the first two goals, but not the last. A few days after the event, the pageant organizers learned to their dismay that the sold-out event had actually lost money. The high costs of the production had forced them to take out loans, and ticket sales and merchandise failed to generate enough of a profit. Dodge, Reed, and others had been frivolous with their spending and did not take the necessary precautions to make sure that the event earned a profit. They spent huge sums of money in renting Madison Square Garden, a special train, and an assortment of props. Fifteen thousand programs were printed at a high cost, yet the organizers didn’t arrange for enough people to sell them on the night of the show and ten thousand programs were later discarded. Additionally, the short three-week time span devoted to organizing an event of this scale was not enough time to cover all the bases needed to avoid any pitfalls.

The blame for the financial loss, however, fell largely upon the IWW, setting up a disastrous public-relations scenario that the corporate media took joy in exploiting. In Paterson, Haywood and other IWW leaders received a cold reception from the strikers, who expected that their work would at the very least generate money for the relief fund.

The strikers became even more inflamed when they learned that Reed and Dodge had bolted to Florence, Italy, the following day for vacation.

![A. Lessig, Bill Haywood, Patterson, ca. 1913 (LC-B2- 2658-9 [P&P], Library of Congress, Flickr Commons Project)](images/f0096-01.jpg)

A. Lessig, Bill Haywood, Patterson, ca. 1913 (LC-B2- 2658-9 [P&P], Library of Congress, Flickr Commons Project)

Reed later noted that he suffered from exhaustion and the trip was a way to recover both physically and mentally, but the timing was poor. To the silk workers who did not have the opportunity to go on such a vacation, Reed’s and Dodge’s departure symbolized the privileged position that many Greenwich Village artists and intellectuals occupied, and contributed to the sense that their involvement had simply been temporary—that they could abandon the struggle at their own convenience. This was not the case with Reed—he remained active, reporting on and partaking in both the Mexican Revolution and the Russian Revolution. Yet, the message that Reed and Dodge conveyed had deep consequences that influenced not only the workers’ impression of them, but the Greenwich Village scene itself; they jeopardized the trust and collaboration that had been built between the Paterson workers and the New York artists over the duration of the strike.

![]()

The strike collapsed seven weeks after the pageant, with workers returning to their jobs without making significant gains. The 25,000 silk workers and their families were in desperate need of food and holding out in these conditions proved to be impossible. During the aftermath of the strike, IWW organizers searched for answers as to what had gone wrong. Flynn offered her perspective in a speech entitled “The Truth About the Paterson Strike,” delivered on January 31, 1914, at the New York Civic Club Forum.18 Flynn examined a number of factors in the strike’s collapse, one of them being the Paterson Pageant, which she referred to as both the high point of the strike’s success as well as the source of its decline. She emphasized the loss in morale when funds were not received, but her other points are both compelling, and contentious, for she raised doubts about the overall value of using art—a pageant—to aid with workers’ struggles.

Flynn criticized the pageant for distracting the workers from focusing on the strike itself. She explained that while the workers were engaged in rehearsing, maintaining the picket lines was cast aside, allowing the first scabs to enter into the mills. She labeled the workers’ shift in priorities as “turning to the stage of the hall, away from the field of life.”19

Flynn also pointed out that while 1,000 strikers took part in the pageant, others were left behind. Her criticism was aimed at the Greenwich Village artists and intellectuals when she stated, “I wonder if you ever realized that you left 24,000 disappointed people behind? The women cried and said, ‘Why did she go? Why couldn’t I go?’ . . . Between jealousy, unnecessary but very human, and their desire to do something, much discord was created in the ranks.”20 Flynn noted that the pageant itself was “splendid propaganda for the workers in New York,” yet she stressed that its overall effect upon the strike was negative.21

Flynn’s analysis, however, merits critique.22 She failed to acknowledge the pageant’s success in both generating press for the strike and the influence that it had on those who took part in the performance.23 One wonders if her critique would have been so harsh had the pageant earned a substantial amount of money for the relief fund. More significantly, had the pageant raised money—would that have boosted the silk workers to victory?

Art Young, Uncle Sam Ruled Out (Solidarity, June 7, 1913, courtesy of Charles H. Kerr Publishing Company)

A case can be made that it would not have. A boost in relief funds would have extended the strike, but the manufacturers showed little evidence that they would move from their position of nonnegotiation. Their ability to operate mills in Pennsylvania had allowed them to stonewall the strikers. Additionally, silk cloths were not viewed as a necessity and the general public was not exactly clamoring for an end to the strike.

The manufacturers were dead set against negotiating with the IWW, which they viewed as a hostile group of outside agitators who had misled Paterson workers—despite the fact that it was the workers who initiated and led the strike. Many workers might have been singlemindedly focused on their conditions, but the manufacturers clearly understood the larger implications of the strike. To them, it was also about broader class struggle. If the Paterson mill owners caved in to the IWW, other labor victories might follow in the future. At stake was maintaining management’s position within the capitalist order. Manufacturers felt it imperative to confront the revolutionary tide of the IWW, immigrant workers, socialism, and anarchism, and they did so with the force of the government, the law, and the corporate press lined up behind them.

Paterson represented a major defeat for the IWW. Its reputation among workers suffered, and the months following the strike saw divisions and infighting within the organization. The year 1913 would mark the IWW’s decline from prominence on the East Coast, and it never truly recovered.24 After Paterson, the IWW turned its focus to the West, organizing migrant laborers in mining and lumber towns.

Paterson was also a tremendous loss for those who believed in the revolutionary potential of artists collaborating with working-class movements in the United States. The bitterness that swept Paterson poisoned the positive memories of the pageant and the possibilities that it presented. Artists involved with the strike had left the isolation of their studios and their small circles, and had used their talents for a greater cause. The defeat sent many of these same artists, although not all, back to the confines of their studios and isolated scenes.

Also forgotten was the initial reason for becoming involved. Hadn’t artists become active with the Paterson strike because they were deeply inspired by the actions of the silk workers and signs that revolution was moving beyond theory and into practice? It had, and the Paterson strike gave artists the opportunity to actively engage in a working-class struggle of national and international significance.25 However, the defeat of the strike made it seem as if the very involvement of artists with strikes was problematic—a notion that was further encouraged by Flynn’s critique of the pageant.

This notion was one of the many tragedies of the Paterson strike for solidarity matters. The Paterson Pageant represented a unique collaboration between three different groups—artists, IWW organizers, and silk workers—each with their own strengths and weaknesses. This collaboration—an act in solidarity in itself—allowed each group to learn from the other, and forced them to question their previous biases and assumptions about each other.26 The pageant gave these different groups the opportunity to work together, with each side contributing its own set of skills. It presented the opportunity for trust and understanding to exist between working-class people and bohemian artists, something that was as uncommon then as it is today.27

In Paterson this collaboration ultimately fell short, and a defeat—any defeat—raises doubts about the merits of specific alliances. In hindsight, one wonders what would have happened had the IWW allowed creative forms of resistance to emerge out of the 25,000 silk workers on strike? In Paterson, the IWW negated a key aspect of their own practice: allowing IWW culture to emerge from within—from their own workers. In Paterson, they brought in artists from New York City and “instructed” the silk workers how to use culture in their struggle. In essence, they placed greater trust in outsiders than the workers themselves. This decision caused anger and distrust to boil over when the pageant failed to deliver on its promise of funds, but the benefit of hindsight is always 20/20. What if the fragile alliance had worked? At the very least, the pageant served as a moment when outside artists attempted to aid a working-class struggle. It fell short, but the lessons should not be to abandon these types of alliances and acts of solidarity, it should be to improve upon them, and to persist, especially in defeat.