IN THE 1910S, THE GREATEST threat to labor and anticapitalist movements was the United States’ entry into World War I. War, as it always seems to do, brought forth a tidal wave of patriotism that the government used as an excuse to stifle dissent.

World War I is particularly extreme example. President Woodrow Wilson lobbied heavily for the passage of the Espionage Act in 1917 and the Sedition Act in 1918, which made speaking out against the war illegal. Part of section 3 of the Espionage Act reads:

Whoever when the United States is at war, shall willfully cause or attempt to cause, or incite or attempt to incite, insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny, or refusal of duty, in the military or naval forces of the United States, or shall willfully obstruct or attempt to obstruct the recruiting or enlistment services of the United States, and whoever, when the United States is at war, shall willfully utter, print, write or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United States or the Constitution of the United States, or the military or naval forces of the United States, or the flag of the United States, or the uniform of the Army or Navy of the United States into contempt, scorn, contumely, or disrepute, or shall willfully utter, print, write, or publish any language intended to incite, provoke, or encourage resistance to the United States . . . shall be punished by a fine of not more than $10,000 or the imprisonment for not more than twenty years, or both.

These acts were part of the “Red Scare,” a domestic battle against antiwar and anticapitalist activism. The weight of these draconian laws came down especially hard upon labor leaders, socialists, and anarchists. More than 2,000 people were persecuted under the Espionage Act.1

In 1919, Eugene V. Debs of the Socialist Party was sentenced to ten years in prison, and served three, for making a speech that obstructed recruiting. In 1920, he campaigned for president from a prison cell in Atlanta and received 913,664 votes (3.4 percent), the largest total ever for a Socialist Party presidential candidate in the United States. His famous campaign pin featured a portrait of him behind bars with the slogan, “For President Convict No. 9653.”

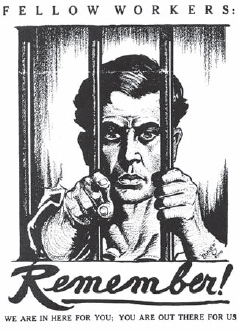

Also during the Red Scare, Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) members became, in the words of labor historian Franklin Rosemont, “members of what is probably the single most incarcerated organization in US history.”2 In September 1917, the government raided IWW offices in more than fifty cities in an attempt to destroy the organization. Documents and artwork were seized or destroyed and leaders were rounded up, put on trial, sent to prison, and sometimes killed. All told, more than one thousand IWW members would be arrested under the Espionage Act.

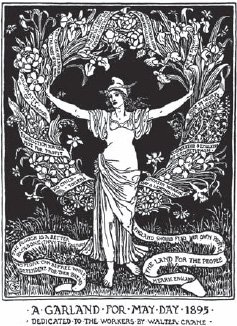

The Espionage Act ensured that war resisters would be jailed, and that antiwar publications would be banned. This was the fate of the socialist magazine The Masses, founded in 1911, and silenced in 1917 after government harassment forced it out of business. During its run, however, The Masses was a vital publication, a clearinghouse of radical art and politics, one that painted a picture of the spirit of dissent found in the 1910s, prior to World War I.

Ralph Chaplin, poster for the IWW defense effort, (Solidarity, August 4, 1917, courtesy of Charles H. Kerr Publishing Company)

Located in Greenwich Village—the epicenter of bohemian culture in New York in the 1910s—The Masses was a group of artists and writers who sought to promote both socialism and individual free expression. In an eclectic format, political essays coexisted with poetry and visual art, some of which was didactic, some more experimental and whimsical. The subtext of the magazine was an internal conflict over its identity. Was it a socialist publication dedicated to revolutionary politics and working-class movements? Or was it a journal that honored the creative arts, expressed through the spirit of bohemian lifestyles and individuality? This dilemma was never truly resolved, creating tension from within the group and generating criticism from outside; yet this hybrid approach was precisely what made the publication so vital.

The Masses was unique, for it embraced the socialist movement while rejecting the doctrine of a strict ideological stance, rejecting both the Socialist Party line and the conservative cultural norms of the day.3 Other publications filled the role of party building, most notably the International Socialist Review and magazines that followed in the wake of The Masses—The Liberator and The New Masses. Yet The Masses was different, for it chose to operate around the periphery of socialism. There, it could both critique and champion the socialist movement. Most important, it made individual freedom the ground rule for its engagement in the movement.

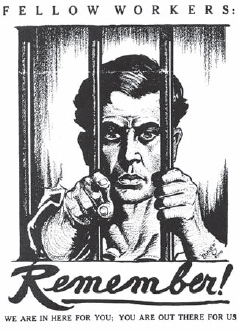

The Masses was unique, but it was not the first socialist magazine to merge politics with art and poetry. The Comrade (1901–1905) had earlier blazed this path and was more utopian with its message. Prints by the British artist Walter Crane complemented poems and essays from people ranging from Walt Whitman and Jack London to Eugene Debs and Mother Jones.4

Walter Crane, A Garland for May Day, 1895 (Interference Archive)

The Comrade was ahead of its time, but a small circulation of only a few thousand copies limited its overall influence, and after four years of existence it merged with the International Socialist Review. The Review (a Chicago-based Charles H. Kerr publication) had also pioneered the use of visual art within a political magazine, primarily photographs taken by amateurs documenting labor strikes. The Masses followed more closely in the footsteps of The Comrade and utilized illustrations as a central feature.

Piet Vlag (a Dutch immigrant who championed small workers’ cooperatives) founded The Masses in 1911, and for the first year it existed as a relatively safe and mainstream socialist publication. Vlag’s tenure was short-lived. The magazine failed to generate much interest, and he left the project behind him. Luckily, artists on the staff, including Art Young and John Sloan, resurrected the magazine and recruited Max Eastman (who at the time was a philosophy instructor) to become the editor in December 1912, a job opportunity that started without pay.

Eastman wanted both to move the publication toward the far left and to “make The Masses a popular Socialist magazine—a magazine of pictures and lively writing.”5 Key artists, in addition to Young and Sloan, included Maurice Becker, Henry Glintenkamp, Robert Minor, Boardman Robinson, and two artists who would, along with Sloan, later become synonymous with the Ashcan School: Robert Henri and George Bellows. All of these artists donated their time and energy, and the magazine honored both their politics and their art. The layout of the art was exceptional, as was the printing quality and the space afforded to the images.

Most important, the magazine belonged to the artists. Decisions, including which images and articles were to be included, were voted upon, although the editor’s opinions carried more weight. The credo of The Masses at the time that Eastman took over as editor read:

A revolutionary and not a reform magazine; a magazine with no dividends to pay; a free magazine, frank, arrogant, impertinent, searching for true causes; a magazine directed against rigidity and dogma wherever it is found; printing what is too naked or true for a money-making press; a magazine whose final policy is do as it pleases and conciliate nobody, not even its readers—there is room for this publication in America.6

An average of 14,000 readers a month supported this sentiment. The Masses reached out to a middle-class audience, those in the loop and those who had yet to commit to socialism.7 The Masses hoped that their editorials, essays, poems, and illustrations would persuade many to join the socialist movement. Their approach was to publish a wide array of stories and art to appeal to a wide audience. Eastman emphasized this point:

We shall print every month a page of illustrated editorials reflecting life as a whole from a Socialist standpoint. . . . In our contributed columns we shall incline towards literature of especial interest to Socialists, but we shall be hospitable to free and spirited expression of every kind—in fiction, satire, poetry and essay.8

A commitment to free expression was what made the magazine so important, but it also left it open to criticism by those who desired a more disciplined approach to revolutionary organizing and Socialist Party–building. One conservative socialist critic, W.J. Ghent, wrote that The Masses mixed:

Socialism, Anarchism, Communism, Sinn Feinism, Cubism, Sexism [free love], direct action and sabotage into a more or less homogenous mess. It is peculiarly the product of the restless metropolitan coteries who devote themselves to the cult of Something Else; who are ever seeking the bubble Novelty at the door of Bedlam.9

Another letter mailed to the magazine, in November 1916, took aim at its choice in lifestyle as truncating its sincerity to politics. “As to your actual ideas, you are, I fear, merely sentimentalists in revolt. The poses that you assume may be indigenous to Greenwich Village, but they can only repel everyone who is seriously at work.”10

Bain News Service, Max Eastman, no date recorded (LC-DIG-ggbain-05770, Library of Congress)

This letter had a point. The commitment of The Masses to controversial issues, including its support of free love and birth control, did alienate certain people, including some industrial workers and recent immigrants who tended to be more socially conservative. Yet the letter failed to recognize The Masses’ genuine commitment to revolt through cultural resistance. Lacking in the letter’s analysis is that culture works in tandem with politics, and can influence public opinion in ways that politics alone cannot. The Masses consistently challenged societal norms—from conservative attitudes over marriage, dress, sexuality and birth control to the public willingness to embrace the government’s entrance into World War I.11

The Masses covers expressed the magazine’s uncompromised position and its commitment to a wide range of approaches and ideas. Some covers were politically vague—an image of fashionable women, for example—whereas others responded to political flash points. One of the more riveting cover illustrations to appear on The Masses was John Sloan’s drawing for the June 1914 issue; it depicts the Ludlow Massacre in Colorado, which had taken place only five weeks before, on April 20, when the Colorado National Guard opened fire on a tent colony of 1,200 striking coal miners and their families, killing an estimated eighteen men, women, and children.12

Sloan’s illustration depicts a miner as he holds a dead child in his arms. Behind him, the sky is ablaze with flames. Everything about the image is meant to elicit sympathy toward the striking miners. Below the illustration, the title of Max Eastman’s article, “Class War in Colorado,” further framed the meaning of the illustration.

These types of stories and illustrations made The Masses a target for governmental scorn and censorship. The Magazine Distributing Company in Boston and the United News Company in Philadelphia refused to carry it, as did two major distributors for the New York City subway stands, ostensibly because they objected to a poem and a cartoon that they deemed unpatriotic and blasphemous.13 Likewise, the Canadian mails refused to deliver it.

The Associated Press (AP) went after Art Young and Max Eastman for a cartoon and an editorial that blasted the AP for siding with the interests of the government and corporate power during a coal miners’ struggle in West Virginia in 1913. Young’s image depicted the Associated Press pouring a bottle of lies into a reservoir that a large city depended upon for its news information, and Eastman explained the story in an editorial entitled “The Worst Trust.”14 The case might have gone to court, but the AP backed away from pressing charges for libel when supporters rallied around Young and Eastman, and realized that press coverage from the court case would likely do it more harm than good.

Yet these attacks seem trivial compared to the internal strife at The Masses, which came to a head in 1916. John Sloan and a number of other artists, including Stuart Davis, resented the fact that the editors would add captions beneath their drawings. They argued that the captions compromised their artistic independence and obstructed the open-ended reading of the illustrations. At the core of the debate was whether the content of the magazine should fulfill socialist propaganda needs, or if some items could stand alone as art and poetry, regardless of whether it included radical content. This dispute was ironic, for the strength of the publication was the fact that it honored both.

Nonetheless, egos got in the way. Pay also created friction. Max Eastman and Floyd Dell, the managing editor of The Masses, were paid a monthly salary, but the visual artists did not receive any financial compensation. Sloan argued for more monthly meetings and the elimination of the position of the editor and the managing editor. However, Eastman countered that everything could not be done by consensus, that the editor had to make decisions over the quality of submissions whereas consensus would mire the entire process in endless debates. He also justified his salary based upon the work that he did in fund-raising and the daily operations of running the magazine.

The division was not simply between artists and editors. Art Young, one of the main illustrators, blasted those in Sloan’s camp: “To me this magazine exists for socialism. That’s why I give my drawings to it, and anybody who doesn’t believe in a socialist policy, as far as I go, can get out.”15 In the end, socialism won. The group voted in favor of Eastman, ultimately resulting in Sloan, Stuart Davis, Glenn O. Coleman, and others walking away from the magazine.

Their departure proved to be relatively inconsequential, as other talented artists, including Robert Minor and Boardman Robinson, were brought into the fold. The renewed Masses became even more dedicated to politics, and advocated strongly against the U.S. entry into World War I. Floyd Dell vocalized the importance of the magazine’s antiwar stance:

John Sloan, Ludlow, Colorado (front cover of The Masses 5, June 1914, courtesy of American Radicalism Collection, Michigan State University Libraries)

All that could be done was, in a world gone insane, to keep alight a little flame of intelligence—to keep on telling the truth as long as we could. . . . And The Masses became, against that war background, a thing of more vivid beauty. Pictures and poetry poured in—as if this were the last spark of civilization in America. . . . A few of us could be sane in a mad world.16

The Masses labeled the conflict as a “bankers’ war,” a war that served the wealthy at the expense of working-class people, regardless of their nationality.

This position was consistent with that of the Socialist Party of America, which denounced World War I at an emergency convention in St. Louis in 1917. Yet this position was not universal among socialists. Many socialists feared that an antiwar stance would erode support for socialism and that it would potentially open them up to government harassment. This fear became a reality for many socialists, including The Masses, in 1917.

In July, the United States Postal Office informed The Masses that the August 1917 issue would not be allowed access to the mails. The Post Office claimed that the issue had violated the Espionage Act and urged the government to prosecute. Specifically, the Post Office claimed that four cartoons and four editorials weret reasonous.17

Those charged included Max Eastman, for an article about resisting the draft; Floyd Dell, for writing a foreword to a collection of letters by conscientious objectors in English prisons; John Reed, for an article on the high levels of mental illness found among soldiers; and Josephine Bell, for a poem celebrating Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman. Merrill Rogers was indicted for simply being involved with the publication. Finally, Art Young and Henry Glintenkamp were charged for cartoons that were deemed seditious material.

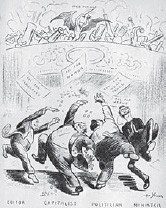

Art Young’s cartoon “Having Their Fling” was singled out for ridiculing the hypocrisy of people in power, including a politician, editor, businessman, and a minister who preach dignity and goodwill while at the same time supporting the carnage of warfare.

Will Hope, Glory (front cover of The Masses 8, June 1916, courtesy of American Radicalism Collection, Michigan State University Libraries)

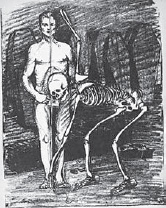

Glintenkamp’s offending cartoon, “Physically Fit,” depicts a skeleton measuring a young soldier for his coffin size before the soldier goes off to the war.

The image did not stray far from reality—it referenced a mainstream newspaper article noting that the Army had placed a large order for coffins in anticipation of a high death toll.18

The looming April 15, 1918, court date did not stop The Masses from continuing to voice its dissent against the war. The September 1917 issue mocked the Post Office’s refusal to carry the August issue, and a statement on the back cover let readers know that The Masses would not be easily intimidated:

Twelve to fifteen hundred radical publications have been declared unmailable. The Masses is the only one which has challenged the censorship in the courts and put the Government on the defensive. Each month we have something vitally important to say on the war. We are going to say it and continue to say it. We are going to fight any attempt to prevent us from saying it. The Masses has proved in the last few issues that it stands as the foremost critic of militarism.19

The threat of jail did not dim their sense of humor. Those facing indictment mailed postcards to one another that read “We expect you for the—ssh!—weekly sedition. Object: Overthrow of the Government. Don’t tell a soul.”20 Not to be outdone, Art Young circulated a form letter that read “Dear Bill: Come to the conspiracy Tuesday night. Yours, The Conspirators.”21

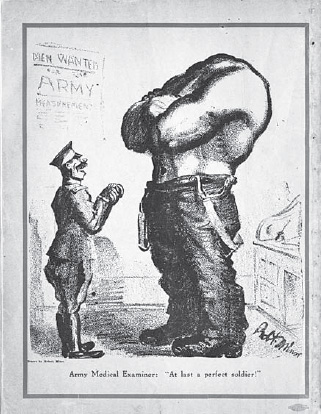

Robert Minor, Army Medical Examiner: “At Last a Perfect Soldier!” (back cover of The Masses 8, July 1916, courtesy of American Radicalism Collection, Michigan State University Libraries)

The trial itself, held in New York City, also had moments of pure absurdity. On the first day of the trial, the solemn mood of the courthouse was disrupted by patriotic songs that echoed from outside provided by a band (unrelated to the trial proceedings) that was hired to help sell Liberty Bonds on the busy New York streets. Merrill Rogers decided to poke fun at the irony of the situation by jumping from his seat and saluting the flag every time “The Star-Spangled Banner” was played. This was not exactly the behavior the jury might expect from someone being charged with sedition against the government.

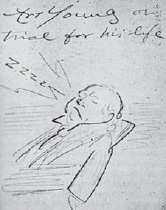

Art Young offered even more comic genius. Falling asleep during most of the trial, his first impulse upon waking up was often to sketch scenes from the courtroom as if he were a reporter. His best courtroom drawing, entitled “Art Young on Trial for His Life,” depicts him sound asleep in his chair.

One of Young’s lawyers, Dudley Field Malone, later attempted to sell the jury on Art Young’s congenial personality by stating, “Everybody likes Art Young. Look at him. There he sits—like a big friendly Newfoundland dog. How could anyone conceive of him playing the role of a conspirator?”22

Art Young, Having Their Fling (The Masses 9, September 1917)

Floyd Dell also proved difficult to cast as a conspirator. His opinions against the war had changed drastically once Germany had attacked the Soviet Union, inspiring him to enlist in the military. Dell believed the war “was going to help Soviet Russia and the cause of Revolution.”23 These views may seem naïve today, considering how authoritarian the Soviet Union became, but at the time, the promise of what appeared to be a genuine worker-led coup in Russia in 1917 inspired people throughout the world to support the Bolshevik Revolution. Furthermore, Merrill Rogers had come to support the war; as did Max Eastman, who bent over backward to express his shift toward patriotism when he appeared in court on charges of violating the Espionage Act:

My sentiments have changed a great deal. You notice when it [the national anthem] was played out there in the street the other day, I did stand up. Will you let me tell you exactly how I felt? I felt very sad; I felt very solemn, very sorrowful because I thought of those boys over there dying by the thousands, perhaps destined to by the millions, with courage and even with laughter on their lips, because they are dying for liberty. And I thought how terrible a thing it is that while they are dying over there . . . the Department of Justice should be compelling men of your distinguished ability, and others like you, all over the country, to waste their time persecuting upright American citizens, when they might be hunting up spies in this country, and prosecuting them.24

Henry Glintenkamp, Physically Ft (The Masses 9, October 1917)

However, Eastman’s comments in court did him little good. He alienated himself from many of his supporters, including John Reed, who was so revolted by Eastman’s comments, and his support for Wilson, that he resigned from the magazine.25 The judge, Augustus Hand, also showed little sympathy. He advised the jury as they deliberated, “And so, gentlemen of the jury, I confidently expect you to bring a verdict of guilty against every one of the defendants.”26 Forty-eight hours later, the jury of twelve returned without a verdict. Although ten had cast a guilty vote, two jurors refused to cooperate, resulting in the case being deemed a mistrial, and the stage was set for a second trial against The Masses.

Art Young, Art Young on Trial for His Life (The Liberator, June 1918)

Crystal Eastman, Art Young, Max Eastman, Morris Hillquit, Merrill Rogers, and Floyd Dell outside courthouse, ca. November 1917 (New York Call, November 22, 1917)

The second trial differed from the first and placed more emphasis on putting the war itself on trial. This time John Reed was present. He had missed the first trial while he was in Russia, but made the decision to return to the United States and face prosecution with his comrades.

All of the defendants assumed that they would be convicted, but once again the jury could not reach a verdict, resulting in another mistrial. One juror remarked to the defendants, “It was a good thing for you boys that you were all American-born; otherwise it might have gone pretty hard with you.”27 This comment illuminates the privileged position that many of the artists and editors of The Masses held. Their politics went against mainstream America, but they also shared many similarities to the jury that determined their fate. They were white, middle-class, and well educated. Had they not been, it is unlikely that they would have been spared.

The courtroom trials spelled the end of the magazine. The U.S. Postal Service, fulfilling the Red Scare tactics of the federal government, ended The Masses, declaring that it was no longer in circulation because it had not been in circulation during the month of August. Denied access to the mails, The Masses could not stay financially afloat. In 1918, The Masses resurrected itself as The Liberator, and continued until 1924, but The Liberator’s content and approach differed greatly from The Masses. The Liberator included art, but the overall content of the magazine showed blind support for the Bolshevik Revolution—a direction that was cemented when the publication was turned over to the Workers’ Party in 1922. Another follow-up publication, The New Masses (1926–1948), took this approach to the extreme, becoming an organ for the Communist Party USA. Gone was The Masses that had reached a middle ground—open to both activism and bohemian culture—one whose credo in 1913 boldly stated: “A magazine directed against rigidity and dogma wherever it is found.” Those days ended with the First Red Scare, the Russian Revolution, and World War I.

“Silent sentinel” Alison Turnbull Hopkins at the White House on New Jersey Day, January 30, 1917 (photograph published in The Suffragist 5, no. 56, Feb. 7, 1917)