ON DECEMBER 29, 1932, Samuel Brody reported in the Daily Worker on the second National Hunger March, a Communist-led march where 1,600 marchers representing the Unemployment Councils marched to Washington, DC, in columns leaving from Boston, Buffalo, Chicago, and St. Louis, calling on Congress to enact federal unemployment assistance. Brody wrote:

Our cameramen were class-conscious workers who understood the historical significance of this epic March for bread and the right to live . . . we “shot” the March not as “disinterested” news-gatherers but as actual participants in the March itself. Therein lies the importance of our finished film. It is the viewpoint of the marchers themselves. Whereas the capitalist cameramen who followed the marchers all the way down to Washington were constantly on the lookout for sensational material which would distort the character of the March in the eyes of the masses, our worker cameramen . . . succeeded in recording incidents that show the fiendish brutality of the police towards the marchers.1

Brody was not an objective reporter. He was a member of the Workers Film and Photo League (F&PL)—a group of activist filmmakers and photographers who documented labor struggles and anti-capitalist demonstrations. His quote articulated how participants in marches and the mainstream media view the same event through different lenses. One largely glorifies demonstrators; the other vilifies them. One scorns the police; the other praises them. Brody represented the former in both cases.

The F&PL itself was part of the broader cultural movement that was sponsored by the Communist International or Comintern. It was a section of the Workers’ International Relief (WIR), an American chapter of the Comintern-supported Internationale Arbeiter-Hilfe (IAH) that Lenin had called for in Berlin in 1921 to provide famine relief for the Soviet Union.2 After that, it expanded to other countries providing relief—food, clothing, and shelter—to striking workers and their families. Early WIR relief efforts in the United States included aiding the textile strikes at Passaic, New Jersey (1926–1927), New Bedford, Massachusetts (1928), and Gastonia, North Carolina, in 1929, along with the miners’ strikes of 1931–1932.3

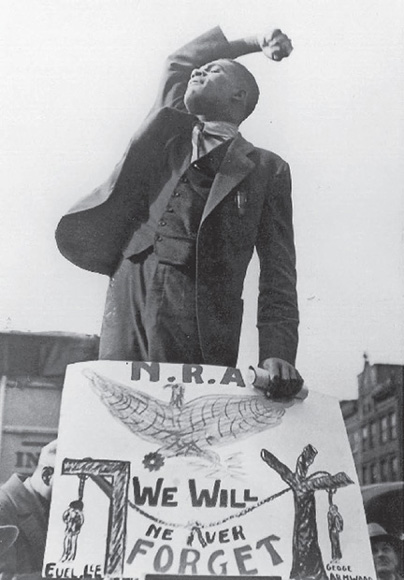

Leo Seltzer, Harlem Demonstration, 1933 (courtesy of Leo Seltzer, via Russell Campbell)

The WIR also focused on agitprop. In Germany, under the leadership of Willi Münzenberg, the WIR produced films, theatre productions, newspapers, illustrated periodicals, and books—all of which promoted the ideals of the Russian Bolshevik Revolution.4 In the Soviet Union, numerous feature-length, black-and-white silent films were released, including Vsevolod Pudovkin’s Mother (1926), The End of St. Petersburg (1927), Storm Over Asia (1928), and Dziga Vertov’s Three Songs About Lenin (1934), among others. The WIR, besides helping to produce Soviet films, also began distributing them—most notably Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925)—using culture as a key tactic to spread the ideas of the revolution and to draw in new recruits. Russell Campbell writes:

In the U.S. the WIR affiliate, at first known as the Friends of Soviet Russia, had been involved with film distribution since its founding in 1922. Throughout the decade it arranged nationwide releases of documentaries about the Soviet Union designed to counteract the hostile propaganda emanating from Hollywood, and beginning in 1926 it also handled nontheatrical distribution (and, effectively, exhibition) of Soviet features. This distribution arm of the WIR was to become closely allied with the Workers Film and Photo League.5

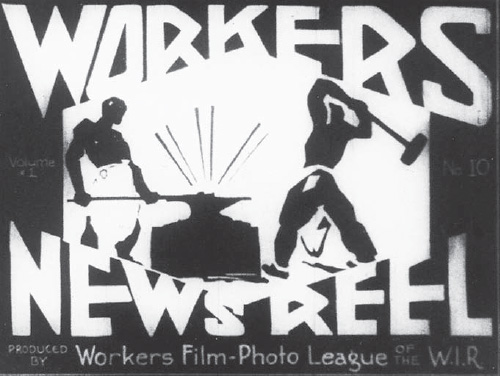

F&PL logo (image courtesy of Russell Campbell)

In New York City, the Workers’ Camera Club, which was allied with the International Labor Defense (the Communist legal-aid organization), evolved into the Labor Defender Photo Group.6 This group, in turn, evolved into the F&PL and began meeting at the WIR Building on 131 West Twenty-Eight Street.7 The NYC branch would eventually include upward of 75 to 100 rotating members but the core of the group remained Samuel Brody, Lester Balog, Robert Del Duca, Leo Seltzer, and Tom Brandon—the latter of whom was a WIR organizer who helped fund and distribute their work. Also important was the film critic Harry Allan Potamkin, who was not technically a member but influenced the F&PL’s direction as it quickly moved beyond just disseminating Soviet workers’ films. A primary motive of the F&PL was to produce their own media. F&PL photographers and filmmakers took part in strikes and demonstrations and filmed their experiences. After shooting an action, the film was then edited into a short newsreel, a silent black-and-white film. The newsreels were then taken on the road and screened to working-class audiences in union halls, theaters, pool halls, and other makeshift venues across the country.

The same approach was applied to still photography. F&PL photographers documented strikes and demonstrations and supplied images through their National Photo Exchange to labor and Communist newspapers, including the Daily Worker, Labor Defender, Der Arbeiter, Freiheit, and Labor Unity, among others. Stills were also sold to mainstream newspapers and periodicals—including Survey Graphic and Fortune—both for publicity and to generate income for F&PL members. While New York City remained a hub of F&PL activity, other cities formed their own branches, including Detroit (which had upward of twenty members), Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia, Washington, DC, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. Smaller, less influential branches with a half dozen or so members also formed in Paterson and Perth Amboy, New Jersey; New Haven, Connecticut; Pittsburgh; Cleveland, Ohio; Laredo, Texas; and Madison, Wisconsin. The overarching goal that connected all of this work was expressed in the F&PL motto: “The Camera as a Weapon in the Class Struggle!”

Black and Blue Filmmaking

“For me, the Film and Photo League activity was a way of life, often working all day and most of the night, sleeping on a desk or editing table, wrapped in the projection screen, eating food that might have been contributed for relief purposes and wearing clothes that were donated.”

—Leo Seltzer8

Mass unemployment and labor unrest was the backdrop of the 1930s and the Great Depression. Between May 1933 and July 1937 more than 10,000 labor strikes occurred.9 Demonstrations and marches were ever-present, as were activist-artists to cover these events.

In 1930, the F&PL reported on the March 6 International Unemployment Day that took place in cities around the world, including thirty U.S. cities. The New York City demonstration at Union Square drew tens of thousands of people and descended into a full-scale riot when 1,000 police officers attempted to prevent demonstrators from marching down Broadway to City Hall. Police clubs and fire hoses battered the crowd, but no one outside the marchers and bystanders would know this from the mainstream media coverage: New York City police commissioner Grover Whalen had urged the media to minimize coverage of the demonstration and subsequent riot. Brody wrote in the Daily Worker on May 20, 1930:

The capitalist class knows that there are certain things that it cannot afford to have shown. It is afraid of some pictures. . . . Films are being used against the workers like police clubs, only more subtly—like the reactionary press. If the capitalist class fears pictures and prevents us from seeing records of events like the March 6 unemployment demonstration and the Sacco-Vanzetti trial we will equip our own cameramen and make our own films.10

Leo Seltzer, Floating Hospital, New York City, 1933 (courtesy of Leo Seltzer, via Russell Campbell)

This is exactly what the F&PL did, against considerable odds, given that the police targeted the F&PL as members of the demonstration, not journalists. Leo Seltzer, one of the more daring cameramen of the group, later reflected, “People would look at my stuff and they’d say, how’d you get it? Did you have a zoom lens? No! and I have black and blue marks on my hands from being beaten.”11 This degree of engagement produced striking film footage and still images. Seltzer adds:

The commercial newsreels had those big vans for their equipment, and they set the camera up on top. They’d park about a block away with a telephoto lens, and their films never really gave you a sense of being involved. My film had that quality because I was physically involved in what I was filming, and that’s what I think gave it a unique and exciting point of view.”12

Other F&PL members echoed this sentiment. Leo Hurwitz stated that F&PL work

had energy derived from a real sense of purpose, from doing something needed and new, from a personal identification with subject matter. When homeless men were photographed in doorways or on park benches, feeling guided the viewfinder. The world had to be shown what its eyes were turned away from.13

He added, “When you put your hand in your pocket and you can touch your total savings, your life is revealed as not the private thing it seemed before. It becomes connected with others who share your problem.”14

This cultural work was part and parcel with the aims of the larger Communist Party USA movement and was aimed at two intended audiences: those who partook in the same actions that the F&PL had filmed, and other workers who might be inspired by them. Seltzer recalls footage he took of a demonstration in support of the Scottsboro Boys—eight of whom faced the death penalty on trumped-up rape charges:

After we marched into the area in front of the Capitol Building, I got out of the line and started shooting film. Then things started to happen. There were a lot of plainclothes men and police around. The cops jumped at this group and started ripping placards off, and beating people up.15

He continues:

I was filming this one policeman. It was a rainy day, and he had on a heavy, rubberized raincoat. I was about ten or fifteen feet behind him and two or three feet beyond him was the line of pickets, with the Capitol Dome beyond that. That was the shot. And as I was shooting, the cop ran in and grabbed the placard from a black marcher and ripped the cardboard. And there was this marcher with the stick still in his hand. The marcher looked at the bare stick, and the cop was tearing up the placard which said, “Free the Scottsboro Boys,” and suddenly the marcher turned and whacked the cop left and right with his stick. And the cop was so stunned, he just stood there.16

Seltzer was thrown in jail for two days, but his footage was well received by audiences when it was compiled into the film America Today and screened at theaters sympathetic to Communist campaigns. At the Acme Theatre on Fourteenth Street, Seltzer noted, “When that sequence was shown the audience jumped up and said, “Give it to him! Give it to him!”17 Other venues for F&PL and Soviet films were not as friendly. Seltzer recalls an event outside Pittsburgh:

I don’t know who shot the Pittsburgh film, but I went back with a projector to show it to the miners who were still blacklisted. They were still living in tents for the second winter. And I remember I went into the town and stretched this sheet between two houses—the sheriff’s and the deputy’s house on either side—and we expected to be shot at any minute while projecting the film.18

Other cities were determined to stop the screenings. In New York, F&PL members were hauled into court in January 1935 for showing films in their own headquarters.19 In Chicago, Mayor Edward Kelly enforced a ban on all newsreel films that featured rioting or large gatherings, making it impossible to project images of strikes and pickets within the city.20 The situation was more volatile in the South: F&PL members were at times driven out of a town by a mob. To keep safe, Sam Brody would sleep with guns by his bed when he covered the textile strike in Gastonia, North Carolina.21

![]()

Threats of violence or arrest did not stop activist photographers and filmmakers from shooting footage, snapping photographs, or taking films on the road. Lester Balog made a cross-country trip from New York City to California in the spring of 1933 with Edward Royce, a WIR organizer, where they screened New York F&PL newsreels and a Soviet film—Pudovkin’s Mother—in more than fifty cities and towns in workers’ halls, community theaters, pool halls, and private homes.22 At each stop, Balog would screen films and Royce would address the audience. In Milwaukee, the two presented to five hundred people during an antifascist demonstration. In San Francisco, their audience eclipsed one thousand at the Fillmore Workers’ Center. For the next two months they would continue their tour down the California coast to Los Angeles and then up through the Central Valley.

Balog and Royce had arrived in California in the midst of the largest wave of agricultural strikes in the state’s history. In October, they returned to Tulare County, the site of a major cotton strike in the San Joaquin Valley. Balog shot footage documenting the struggle, but he also took an active role in participating in the struggle: he created a ten-foot banner that was used during a funeral of a Mexican worker who had been killed. In the weeks that followed he continued to make graphics and took part in meetings of the strike committee.23 Balog demonstrated a common thread with F&PL members: they participated in struggles, documented them, and promoted them to other workers.

In San Francisco, Balog helped energize the San Francisco chapter of the F&PL. They set up shop at the Workers’ Cultural Center at 121 Haight Street—also called the Ruthenberg House—that included a workers’ school, a restaurant, a library, a ballroom, classrooms, and a darkroom for the F&PL. Here Balog edited short newsreels of the 1933 cotton strike and worked on a more ambitious film—Century of Progress. He was also listed as a cinematography instructor for the workers’ school in the spring 1934 catalog. Along with Otto Hagel, Balog taught a class that mirrored their activist-art practice; it was described as a study of the “criticism of bourgeois practices, analysis of Soviet newsreels, documentary and acted films, Montage, film production and projection of working class newsreels and films.”24

That spring, Balog, accompanied by Hagel, toured California again, traveling to Los Angeles and back up through the Central Valley. In a pool hall in Tulare County—the site of the cotton strike the prior year—they set up an impromptu screening of the F&PL film Cotton-Pickers’ Strike and the Soviet film Road to Life and screened it to an audience of 75 to 100 Mexican migrant laborers, the majority of whom were under twenty years old.25 The four-hour event ended when four police officers arrested Balog and Lillian Dinkin, a CP USA organizer, and charged them with running a business without a license. Both were jailed for thirteen days, then brought before a jury who deliberated for five minutes and found them guilty, handing out a forty-five-day sentence and a hundred-dollar fine. Their incarceration coincided with the San Francisco General Strike that was led by the International Longshoremen’s Association and succeeded in completely shutting down the city from July 16 to July 19. Balog and Dinkin were released on July 17 and returned to a tense situation: vigilantes had completely destroyed the Ruthenberg House, leaving the F&PL’s darkroom in ruins. With their space destroyed and much of their equipment impounded, the San Francisco F&PL fell apart less than a year after it had been started.26

Leo Seltzer, New York City Demonstration, 1933 (courtesy of Leo Seltzer, via Russell Campbell)

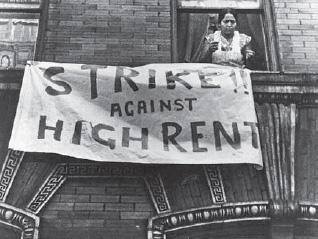

Leo Seltzer, Rent Strike East Harlem, 1933 (courtesy of Leo Seltzer, via Russell Campbell)

Newsreels or Art and F&PL Film Criticism

Other F&PL branches across the United States imploded over longstanding divisions over the artistic direction and the content of the films. In the New York F&PL, a number of filmmakers left to form Nykino—a more experimental, narrative film group—because they wanted the creative freedom to expand beyond agitprop work.27 In other cases, individual artists who remained with the F&PL had to make numerous compromises. William Alexander writes:

When Lewis Jacobs went south to film in the straitened mining communities, he expected to return to edit his material and shape a film. Instead, he was asked to turn over the footage to the League, with no explanation of what was to become of it. Some of it was edited—supposedly under the eyes of those with the “correct” political savvy—along with other footage, into Strike Against Starvation. Jacobs, who gained some valuable shooting experience at League cost, did not complain.28

This strict approach often led to infighting and members being dismissed, which was the case in the F&PL. Isador Lerner was unanimously expelled from the F&PL after he returned from the Soviet Union and reported to the New York group that Russia was not the utopian state that many had proclaimed it to be, and that he had witnessed many people on the brink of starvation.29

Ruthenberg House after the 1934 attack (Sid Roger Photo Collection, Labor Archives and Research Center, San Francisco State University)

Others criticized the quality of the F&PL’s work. Novelist Michael Gold wrote in the Daily Worker in November 1934: “Our Film and Photo League has been in existence for some years, but outside of a few good newsreels, hasn’t done much to bring this great cultural weapon to the working class. As yet, they haven’t produced a single reel of comedy, agitation, satire or working class drama.”30 Gold, instead, praised Vertov’s film Three Songs About Lenin, but neglected to stress that the F&PL operated on shoestring budgets, making it more difficult to produce features like their Soviet counterparts.

However, critiques and debates over art and propaganda alone did not derail the F&PL. Instead, the organization’s last gasp was the demise of the Workers’ International Relief (WIR) whose base operation in Germany was destroyed by the Third Reich, resulting in the F&PL losing much of its organizational and financial backing.31 Had this not occurred, however, the F&PL would still likely have changed course. In 1935, the Popular Front was introduced at the Seventh World Congress of the Communist International in Moscow, marking a sea change in international Communist strategy. Instead of combating capitalism and capitalist nations, communists were encouraged to enlist Western democracies to create a united front against fascism—specifically a front against Hitler, Mussolini, and the rise of militarism in Japan. CP USA members were instructed to bridge alliances with any and all progressive groups, from labor unions to governments. CP USA changed its approach toward the New Deal, shifting from harsh criticism to a willingness to support some of its agenda. Consequently, the Popular Front’s call for building alliances ended much of the activity of sectarian cultural groups, including the John Reed Clubs and the F&PL, which all but folded by 1936. That year, the film division of the New York F&PL moved to 220 West Forty-Second Street in June, while the photography division remained at 31 East Twenty-First Street and was renamed the Photo League in 1937.32 The Photo League became a major force in documentary photography for more than a decade, before being buried by the Second Red Scare in 1951. The film division, however, closed in 1936. In the decades that followed, much of the F&PL film reels and photographs produced by F&PL were lost or destroyed due to communist witch hunts.

In 1953, Lester Balog was listed as a Communist in the Un-American Activities hearings in California. In an interview with Tom Brandon, he conveyed what had happened to his work:

Burned them! Believe it or not. I must have had seven or eight 400-foot reels, silent, 16mm. And what happens is, there were many people on it, some of whom were Lefts, Communists, Socialists, who were in demonstrations that may have had signs. . . . In ’52, we had some “visitors” and that worried me, and my wife too . . . I didn’t want to incriminate people who may have changed since then . . . after three or four days, I burned the stuff . . . it broke my heart.33

The film reels and negatives were gone, but the concept that lay behind the work—activists creating their own media—could not be so easily destroyed. It resurfaced many times in different forms, ranging from SNCC Photo in the 1960s to Paper Tiger Television in the 1980s and Indymedia in the 2000s. In some cases, F&PL members took a direct role in sharing their past work and tactics with others. In the 1960s, Balog screened Century of Progress during an organizing meeting for the United Farm Workers.34 And Balog’s photographs continued to influence others. In 1941, Balog took the now iconic photo of Woody Guthrie holding a guitar with the words “This Machine Kills Fascists” scrawled across the guitar’s body. In the decades that followed, he remained committed to documenting the labor movement. Together with Otto Hagel, he worked as a photographer for the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, producing images for their newspaper The Dispatcher.

Others remained equally committed despite the harrowing experience of living through the Second Red Scare. Brody remarked in his seventies, “What the ‘politically committed artist’ owes the people at this juncture is revolutionary art dedicated to revolutionary transformations of society. Any other formulation is mere intellectual obfuscation.”35 In words aimed at the younger artists, he added, “We need a new left film organization that would be tailored to the needs of our own time, with a ‘rage’ not merely for film for its own sake, but to put this powerful medium at the service of progress and change.”36

David Robbins, Philip Guston Sketching a Mural for the WPA Federal Art Project, February 15, 1939 (Digital ID# 3027, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, courtesy of the Archives of American Art Wikimedia Partnership)

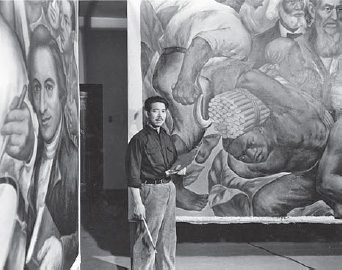

Eitaro Ishigaki standing before his painting Harlem Court, circa 1940 (Digital ID# 2174, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, courtesy of the Archives of American Art Wikimedia Partnership)