Government-Funded Art: The Boom and Bust Years for Public Art

THE 1929 STOCK-MARKET crash that led to the Great Depression ushered in an economic crisis that plunged fifteen million people into unemployment by 1933. Yet the stock market was not the only market to crash. For artists, their market—the art market—also crashed. Galleries closed and private institutions that had once supported the arts became thrifty, leaving artists without patrons, without money for supplies, and without much hope.

This downturn was not new for artists, for their economic standing before the Depression had never been very stable. The printmaker and Artists’ Union organizer Chet La More cautioned, “To the artists, 1929 does not represent an abrupt change, but merely a point of intensification in the process which has slowly been forcing them downward in the economic scale.”1 Yet the Depression was dire, as artists, like the majority of Americans, found themselves searching for work in a sea of unemployment. The solution, many argued, was for the government to fund the arts.

This idea was not without precedent; artists simply had to look south. Beginning in the early 1920s, the Mexican government employed numerous artists to decorate government buildings, a program that sparked the Mexican muralist movement, highlighted by the work of Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros.

In the United States a handful of artists, led by the Unemployed Artists Group, urged their government to follow the same path. The idea was proposed that artists be employed to decorate public buildings, including the new Department of Justice Building in Washington for “plumber’s wages.”2 President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration responded favorably to the idea, and in November of 1933, the first program dedicated to putting artists to work, the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) was enacted under the direction of Edward Bruce within the Treasury Department. The program was limited, employing only a small number of artists and lasting only until May 1934, but it laid the groundwork for subsequent programs, most notably the Works Progress Administration Federal Art Project (WPA-FAP), which marshaled in an unprecedented era of government funding of the arts between 1935 and 1943.

Combined, these programs had a significant effect beyond that of economic relief, for they fostered an environment in which artists were no longer isolated in the studio, or hidden within hermetic art scenes. Instead, they created an era of vast productivity in which artists created a wide range of public art. This art, in turn, reached a mass audience and ordinary Americans were exposed to a vast array of culture, whether it was visual art, music, dance, literature, or theatre. Together, the WPA cultural programs produced a brief window of time when the arts were considered an essential part of everyday life for many Americans across the nation. But the process of artists working for the government was a double-edged sword: a program that came with numerous controversies and compromises, and one that was incredibly short-lived.

Art for the Millions: A New Deal for Artists

“For the present we are busy.”

—Beniamino Bufano, sculptor3

The federally funded art programs followed the basic premise of other New Deal programs: temporary relief for unemployed workers. Artists were just one of many different factions who successfully lobbied for a share of the relief funds. Relief is one way of understanding the era, for the New Deal as a whole represented a major shift whereby the government directly intervened in the economy, giving the president a tremendous amount of executive power. Governmental intervention included the regulation of the stock market and the banking system, Social Security, pensions, unemployment compensation, laws against child labor, creation of public housing, minimum-wage standards, farm subsidy, and the Wagner Act that gave workers the right to collective bargaining. Some programs even hinted at socialism, such as the Tennessee Valley Authority, which involved government ownership of a major utility by operating a series of dams and hydroelectric plants in order to lower the cost of electric bills for consumers in the region.

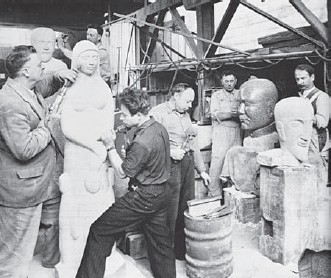

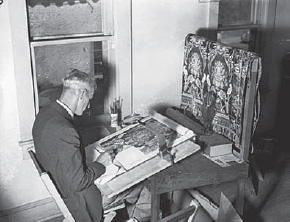

Beniamino Bufano at work in WPA-FAP sculpture studio in San Francisco with Sargent Johnson behind to the right, ca. 1935–1940 (Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution)

For artists, the funding provided jobs and temporary economic security during a period where few other options were available. For most artists, galleries (the few that remained open) did not represent a viable option. The type of work preferred by many gallery owners was narrow and conservative. In New York City, the epicenter for visual art in the United States, fewer than ten galleries exhibited contemporary art during the 1930s on a regular basis, preferring instead to show the Great Masters and other art from the past.4

If anything, the 1930s brought to the forefront the hostility that many artists had long harbored toward the gallery system and their dependence upon it. The fact that many galleries went out of business during the Depression was welcome news to some. The surrealist painter Louis Guglielmi commented:

The private gallery is an obsolete and withered institution. It not only encouraged private ownership of public property, but it destroyed a potential popular audience and forced the artist into a sterile tower of isolation divorced from society.5

Public funding offered a different path for the artist. Holger Cahill, the director of the WPA-FAP, praised public funding as a means by which to counter elitism in the arts.

In a speech entitled “American Resources in the Arts” he explained that

many American artists, many American museum directors and teachers of art, people who would lay down their lives for political democracy, would scarcely raise a finger for democracy in the arts. They say that art, after all, is an aristocratic thing, that you cannot get away from aristocracy in matters of aesthetic selection. They have a feeling that art is a little too good, a little too rare and fine, to be shared with the masses.6

Cahill argued that this approach had distanced art from everyday people and had turned art into a “luxury product” found in a handful of metropolitan areas:

Because, during the past seventy-five years, the arts in America have had to follow a path remote from the common experience, our country has suffered a cultural erosion far more serious than the erosion of the Dust Bowl. This erosion has affected nearly every section of the country and every sphere of its social life. There has been little opportunity for artists except in two or three metropolitan centers. With the exception of these centers, the country has been left practically barren of art and art interest. The ideas and the techniques of art have become a closed book to whole populations which have had no opportunity to share in the art experience, and which, in our industrial age, have become divorced from creative craftsmanship.7

Cahill stressed that a country lacking in public funding in the arts excluded both the urban poor and those living in rural areas.8 His alternative vision was for the WPA-FAP to reach out to every American, to give anyone who was interested the opportunity to participate in the arts.9

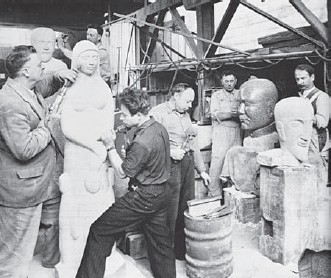

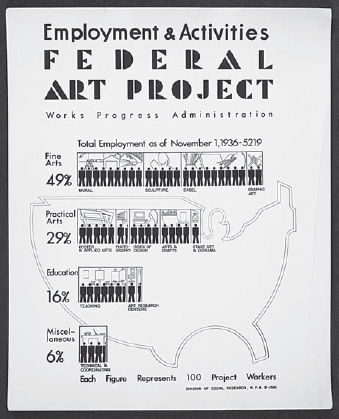

Aubrey Pollard, Holger Cahill Speaking at the Harlem Community Art Center, October 24, 1938 (Digital ID# 12273, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, courtesy of the Archives of American Art Wikimedia Partnership)

The WPA, acting as an umbrella for the Federal Theatre Project, the Federal Writers Project, and the Federal Art Project, accomplished many of these initial goals. Opportunities that had once been dormant now seemed unlimited for WPA employees. Projects ranged in scope from directing plays and writing novels to recording folk songs, recording the narratives of ex-slaves, and painting murals within post offices.

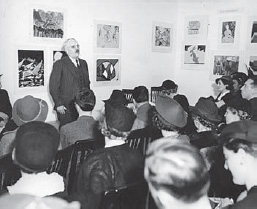

The Federal Art Project included a wide range of opportunities for artists to get involved.10 A 1938 poster charted the various divisions within FAP and described the opportunities for artists to work in various mediums or as teachers, on production crews, and as administrators. Divisions included sculpture, murals, easel painting, photography, graphics, posters, and arts and crafts. Other options including positions devoted to building stage sets, frames, creating dioramas, modeling for artists, and serving as technical advisers (such as print technicians).

Employment and Activities poster for the WPA’s Federal Art Project, January 1, 1938 (Digital ID# 11772, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institute, courtesy of the Archives of American Art Wikimedia Partnership)

The WPA-FAP also established more than one hundred community art centers throughout the country, including the Harlem Community Art Center, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, and the Spokane Art Center.11 Together, these centers were designed to encourage thousands of people to become involved in the arts and not to just cater to artists who were already well established.

Other projects were research-based. One of the more fascinating WPA-FAP projects was the Index of American Design, which employed upward of four hundred artists to record through detailed black-and-white and color drawings a visual record of American design history. Artists worked alongside researchers, cataloging the “history of American decorative and utilitarian design from the earliest days of colonization until the late nineteenth century.”12

Research divisions were established throughout the country, where items ranging from glassware to furniture to clothing were all meticulously recorded. C. Adolph Glassgold, the national coordinator of the Index of American Design, explained the wide breadth of activity:

The Pennsylvania unit, for example, is doing an exhaustive piece of work on the Pennsylvania-German culture; Northern California is busily engaged in re-constructing the era of mining . . . Minnesota is specializing in the early contributions made to American design by the Swedish immigrant . . . Utah is recording the applied arts of the Mormons; New England, with contributions from Ohio and Kentucky, is making what will probably be the first definitive compilation in color of the practical arts of the Shaker Colonies. . . . Were it not for the Index of American Design, the superb costumes, saddle trappings, furniture, and “santos” from the old Spanish Southwest might never have been recorded.13

Significantly, the fact that it was a government project ensured that the records and archives would be in the public domain. The Index of American Design embodied a common goal of the WPA-FAP: putting unemployed artists back to work, encouraging many different types of art forms that would be appreciated by a large audience, and fostering projects that had a social purpose.

Magnus Fossum, a WPA artist copying the 1770 coverlet Boston Town Pattern for the Index of American Design, Coral Sables, Florida, February 1940 (National Archives, Records of the Work Projects Administration, 69-N-22577)

A lesser-known project, the Art Caravan, also followed this model and served as a form of outreach for the WPA-FAP. The Art Caravan consisted of an old army ambulance that literally brought art to the people by transporting a traveling art exhibition.

Inside, the ambulance was converted so that it could haul “six large folding standards on which to hang oil paintings, a number of folding screens for prints, watercolors, and Index of American Design plates, six boxes for packing sculpture, which were also used as stands for its display, a number of folding easels, and other necessary paraphernalia.”14

The driver, Judson Smith, and later Kaj Klitgaard (both of whom were artists and lecturers), drove out to rural areas, where the exhibition was installed on the front lawns of public libraries and in town squares. In the evening, the driver would give a lecture on art to whomever cared to listen. Even more remarkable, a “ballot box” was set up to solicit responses from the audience:

Besides voting for the work they liked best, people were asked whether or not they would be interested in the establishment of a community art center or in obtaining any of the other services of the Project. In every case the vote was overwhelmingly in favor of the initiation of some art activity in the vicinity. The Art Caravan usually found a friendly and curious public during its visit, and some local person with organizing ability, such as the art teacher from the high school, would form a citizen’s committee to develop plans for participating in some phase of the Project’s programs.15

Eugene Ludins, a WPA-FAP supervisor in Woodstock, New York, concluded that it

proved over and over again that the very people who “know nothing about art” are the most easily interested when it is presented to them informally and they are encouraged to express their opinions . . . It has made an entirely new public aware of the WPA/FAP as a functioning cultural influence available even to the smallest village or township.16

Ludins viewed the Art Caravan as only the beginning:

If this experiment could be expanded and the technique improved through further experience, the Art Caravan would become a powerful medium for the introduction of new and vital interests into the lives of thousands of children and adults who are isolated from the big cities but who nevertheless make up the great majority of the people of this country.17

To others, the Art Caravan was elitist, for it assumed that rural people were lacking culture and that the art that was being exhibited would help to educate and enlighten them.18 This argument exposes one of the contradictions of the WPA-FAP that proved difficult to resolve: the dilemma was how to increase artistic culture throughout the United States while at the same time remaining sensitive and open to a wide range of art forms, traditions, and cultural tastes.

Art Caravan, ca. 1935–1940 (NARA Still Picture Branch of the Special Archives Division)

To build a middle ground, administrators respected that different regions of the country (and different communities within these regions) had their own distinct styles. Holger Cahill’s overriding goal was consistent, and that was to encourage people to be involved in the arts through “active participation, doing and sharing, and not merely passive seeing.”19

This inclusive approach allowed WPA-FAP projects to be diverse in style and content and allowed abstraction to coexist with representation, and fine art to coexist with craft. All styles were represented. Many problems and controversies arose, but the primary goal of the WPA-FAP was always to employ out-of-work artists and to expand art throughout the country.

In this regard, the WPA-FAP was incredibly successful. Robert Cronbach, who was employed in the Sculpture Division, reflected years later, “For the creative artist the WPA-FAP marked perhaps the first time in American history when a great number of artists was employed continuously to produce art. It was an unequaled opportunity for a serious artist to work as steadily and intensely as possible.”20 It also was an opportunity that ended quickly.

Red Herrings

Nearly from its inception the WPA-FAP faced funding cuts and program changes that altered its original mission. Attacks against public funding began shortly after the program was launched in 1935.21 Starting in 1936, Congress imposed the first cuts, and by 1937 Congress had slashed 25 percent of its overall budget.22 Two years later, in 1939, more cuts were levied and much of the financial burden for funding the arts was transferred to the states, and artists were limited to an eighteen-month time span for consecutive work on a WPA-FAP project. This action alone disqualified the eligibility of more than 85 percent of New York artists.

Politicians who were hostile to the project’s mission and work simply had to label artists and programs that they did not like as “Communist” in order to either bar them altogether or to greatly limit their influence. This accusation was enough to distance the majority of politicians from any support for the arts that they might have previously had. This attack, however, had a larger agenda, and was not targeted just at Communist groups: it was meant to stop the larger gains made by New Deal programs, along with labor and progressive movements—movements that could not be defined narrowly by a political ideology.

Red-baiting attacks had dire consequences for many, including artists who continued to remain actively engaged in social movements throughout the 1930s and 1940s, whether they had been affiliated with the Communist movement or not. Artists were put under FBI surveillance, blacklisted from jobs and teaching positions, dragged before the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), and faced external and internal pressure to censor their work.

All of the attacks against suspected “red” artists represented an affront to free speech that attempted to curtail First Amendment rights. WPA-FAP artists were made to take a loyalty oath to denounce any affiliation with Communist organizations. These draconian measures resulted in the WPA-FAP becoming cautious and fearful of approving any projects that had an inkling of political content. It also created a climate of self-censorship by the artists themselves.

Despite these attacks and the weakening of public art programs, artists demanded that the federal government expand the WPA-FAP and establish a permanent program. The Artists’ Union crafted the language for a Federal Art Bill in 1935, and in January 1938, Rep. John M. Coffee of Washington and Sen. Claude Pepper of Florida introduced the Coffee-Pepper Bill (H.R. 8239) with the goal of establishing a permanent Bureau of Fine Arts.

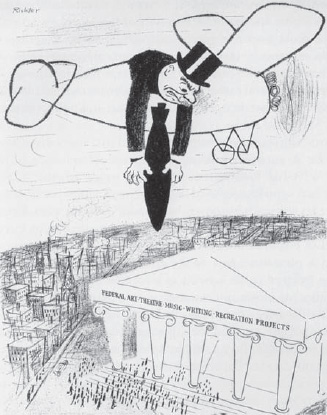

Mischa Richter, First Objective, 1939 (New Masses, 30.5, January 24, 1939)

However, when H.R. 8239 was introduced before the House, the bill was mocked and subsequently tabled by a vote of 195 to 35, which essentially killed it. Opponents labeled the very concept of arts funding during a depression as preposterous. One politician stated that “good art emerged from suffering artists, while subsidized art is no art at all.”23 Others attacked public art programs as harboring radicalism. Rep. J. Parnell Thomas accused the Theatre Project and the Writers Project of being a “hot bed for Communists” and added that the programs were “one more link in the vast and unparalleled New Deal propaganda machine.”24

These attacks ended the possibility of a Federal Art Bill being reintroduced and turned the climate surrounding New Deal programs into a full-scale witch hunt led by the House Un-American Activities Committee, chaired by Rep. Martin Dies. The Dies Committee in 1938 accused 640 organizations, 483 newspapers, and 280 unions of being fronts for communist organizing.25 The WPA-FAP was included in this list, and administrators and artists were forced to testify in its defense. The harshest attack was levied against the Theater and Writers Projects, resulting in the Theatre Program being cut, which spelled the beginning of the end for all federal art programs.

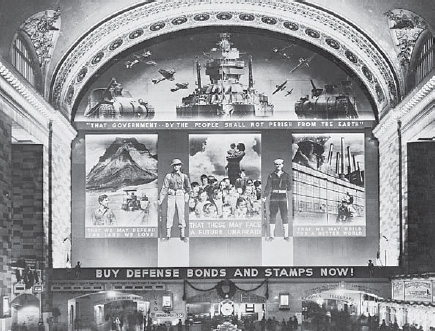

To protect the funding from cuts, WPA-FAP administrators offered the services of the art programs to the war effort to justify the public spending, and to deflect criticism that the programs were havens for Communist art and organizing. By June 1940, Holger Cahill recommended that all art projects focus on defense-related concerns, and by the end of the year the majority of WPA activities had shifted to the production of art for the armed forces and the Office of Civilian Defense.26 Projects included graphic artists making training aids, posters, and silk screens of rifle-sight charts for target practice. Sculptors created models for war machinery, and painters worked on murals for military bases and painted camouflage on ships, tanks, and other objects. The Farm Security Administration (FSA) photographers were transferred to the Office of War Information (OWI) and instructed to make glowing images of the nation preparing for war. One of the photographers, John Vachon, remarked, “We photographed ship yards, steel mills, aircraft plants, oil refineries, and always the happy American worker. The pictures began to look like those from the Soviet Union.”27

As problematic as these OWI projects were, they did not last long. Roosevelt gave the orders that all federal art projects were to come to a close by 1943, noting that the WPA had served the country with distinction and “earned its honorable discharge.”28

Arthur Rothstein, War bond mural, Grand Central Station, New York, New York, 1943 (LC-USF34-024494-D, Library of Congress)

The ease by which the art programs could be cut was telling. From the start, the government had envisioned the programs as temporary relief efforts, lacking longevity, which still left artists as marginalized members of society, engaged in a practice that was not valued as a essential part of the cultural well-being of the nation. Jacob Kainen of the Graphics Art Division stated:

One of the tragedies of the WPA-FAP was that the artists were treated as beggars by the relief-oriented policies of the WPA . . . their creative problems were not understood, and their work was grossly undervalued.29

Their work was also discarded. At the conclusion of the WPA-FAP, numerous paintings and other objects were sent to a government warehouse, where they were subsequently auctioned off for cheap to a handful of second-rate dealers who knew about the closeout sale. Work that didn’t sell was then later destroyed. Discarded also was Cahill’s progressive vision of a nation where art and culture would flourish in all corners of the country. Instead, a few epicenters for visual art would remain viable in New York City, Los Angeles, and to a lesser-degree Chicago. This left many visual artists at the mercy of the free-market system (galleries) to either sink or swim; most sank.

Stuart Davis, Art Front(cover), May 1935 (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)