“The Public Works of Art Project ‘professional wage’ was not food fallen from above. It was won by the persistent demands of organized artists.”

—Boris Gorelick, Artists’ Union organizer1

NONE OF THE RELIEF PROGRAMS that employed artists during the Great Depression—the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) or the Works Progress Administration Federal Art Project (WPA-FAP)—were gifts from a benevolent government. Instead, artists demanded that these programs be created, and when they were, they lobbied to protect them. The Artists’ Union—established in New York City and later expanded to other cities—was the leading voice for unemployed artists during the Great Depression. It was comprised of a militant group of artists organized into a trade union of painters, printmakers, and sculptors. Together, they advocated for more positions in the federal art projects, better pay, and better working conditions; as well, they organized against funding cuts and layoffs.

![]()

In 1933, a small group of around twenty-five artists and writers in New York City began meeting at the John Reed Club—named after the late journalist, founder of the American Communist Party, and the only American ever buried at the Kremlin—and drew up a manifesto. It read, in part, “The State can eliminate once and for all the unfortunate dependence of American artists upon the caprice of private patronage.”2

The group settled on the name the Unemployed Artists Group (UAG) and began lobbying and demonstrating for federal and state jobs for artists. In September, they petitioned Harry L. Hopkins, one of Roosevelt’s closest advisers and one of the architects of the New Deal, and called upon him to create opportunities for muralists, sculptors, graphic artists, and other visual artists to decorate public buildings and to work on public art projects. This call helped create the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP)—a temporary relief program that was established in November 1933 and ended less than six months later.

The PWAP was flawed from the start. The selection process for the six-hundred-plus artists was left in the hands of Juliana Force, the director of the Whitney Museum, and much to the objection of the Unemployed Artists Group, she selected established gallery artists—many of whom were not in need of assistance. In response, the Unemployed Artists Group—renamed the Artists’ Union—staged a total of nine demonstrations outside the Whitney that spurred a change in this procedure. Afterward, artists were called to work in order of their registration number. Eventually, 3,800 artists were assigned to projects, typically lasting from six weeks to three months, and that paid between $27 and $38.25 per week. And when the PWAP was left to expire, the Artists’ Union helped lobby for a new program—the WPA-FAP.

In 1935, the Federal Art Project would launch a new era of temporary relief programs, albeit at a reduced wage—$24 per week for most areas of the country. That same year the Artists’ Union drafted the framework for a Federal Art Bill designed to make government funding of the arts permanent. The Artists’ Union felt that only the federal government had the resources to employ large numbers of artists. In addition, they believed a Federal Art Bill would help promote and distribute visual art throughout all corners of the nation. Artists’ Union organizer Chet La More summarized, “We contend that painting, literature, and theaters do not belong to a top group; that they do not belong to people who can pay $1000 for a painting, and who can pay Broadway prices to see a play. The finer things in life belong to all the people in a democracy.”3 This vision—a permanent arts program—would not arise, but temporary relief programs under the banner of the WPA-FAP would.

The Artists’ Union

“Art has turned militant. It forms unions, carries banners, sits down uninvited, and gets underfoot. Social justice is its battle cry!”

—Mabel Dwight, WPA-FAP printmaker4

Prior to the start of the WPA-FAP, the Artists’ Union in New York City was already a well-developed organization, and by the end of 1934 it had upward of seven hundred members. Meetings were held every Wednesday night, and attendance often fluctuated between two and three hundred people; crisis meetings would draw upward of six hundred.5

Locals were also formed across the country, in Philadelphia, Boston, Springfield (Massachusetts), Baltimore, Woodstock (New York), Cedar Rapids, Detroit, Chicago, Cleveland, St. Louis, Los Angeles, and elsewhere.

By 1936, the WPA-FAP employed more than five thousand artists and well over a thousand of these artists were Artists’ Union members, spread out across eighteen states. Many of the Artists’ Union members, though not all, were also affiliated with CP USA and Communist campaigns. Others were fellow travelers, sympathetic to communism and socialism and the movement against war and fascism. The Artists’ Union, however, distanced itself from direct Communist ties, stating that it would not align itself to any political party. Instead, its primary role was economic—helping unemployed artists obtain work in federal and state art programs, and advocating for the arts to reach all Americans. In short, the Artists’ Union became the mediators between artists and PWAP (and then WPA-FAP) administrators, settling grievances between workers and administrators and threatening to take direct action if needed.

On November 30, 1936, more than 1,200 artists, writers, actors, and actresses gathered in protest in New York City over WPA funding cuts and layoffs. Two days later, on December 1, more than four hundred Artists’ Union members gathered outside the WPA administration offices on Fifth Avenue and Thirty-ninth Street while 219 demonstrators stormed the offices and occupied them. The administration’s response was to call in police, who proceeded to assault them. Twelve Artists’ Union members were badly injured and taken away in ambulances, including Philip Evergood and Paul Block (who had led the demonstration), and all of the demonstrators were arrested.

Artists’ Union demonstration, ca 1936–1937; Byron Brown pictured right front (Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution)

In jail, some gave fake last names to the authorities, claiming to be Picasso, Cézanne, da Vinci, Degas, and van Gogh. A couple days later, the 219 individuals arrested were arraigned in court on December 3, found guilty of disorderly conduct, and given a suspended sentence.

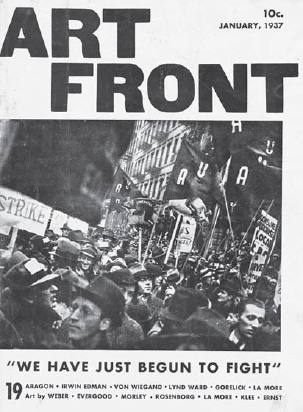

More protests would follow. On December 9, some 2,500 WPA workers orchestrated a half-day work stoppage of all art projects to protest pending dismissals. Three days later, artists joined in with 5,000 other WPA workers in a picket at the central WPA office. The January 1937 cover of Art Front—the Artists’ Union’s official publication—documents their capacity to demonstrate. Visualized is a street packed with protesters; prominent among them are Artists’ Union signs and red banners with the “AU” letters. Also held up high are cutout images of pigs with top hats—a likely reference to bankers.

Art Front (cover), January 1937, (Ben Shahn papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution)

These demonstrations produced results. The street protests, the police brutality at the WPA offices, and the resulting press caused Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia to make an emergency trip to Washington that resulted in funds not being cut. Gerald M. Monroe writes, “While average employment on the WPA as a whole decreased 11.9 percent from January to June 1937, employment on the four Arts Projects increased 1.1 percent.”6

However, this temporary reprieve was short-lived. In April 1937, President Roosevelt and Congress pushed through a 25 percent cut of all WPA funding that did not spare artists. In late June, WPA-FAP employees began receiving their pink slips, setting off another wave of sit-ins by the Artists’ Union and others—writers, musicians, actors, and actresses—who occupied the WPA offices in Washington, DC. In New York, six-hundred-plus demonstrators occupied the Federal Arts Project Office and held Harold Stein, a New York City Art Project administrator, captive for fifteen hours. There, he was ordered to call his superior in Washington, DC, and relay the strikers’ demands that all cuts should be rescinded. Eventually, Stein signed an agreement that the layoffs would be delayed, but in reality Stein had no power in stopping the cuts from eventually going through.

These actions alone represented a new militancy among artists as they began to realize their collective strength. Stuart Davis, the first editor for Art Front, wrote:

Artists at last discovered that, like other workers, they could only protect their basic interests through powerful organizations. The great mass of artists left out of the project found it possible to win demands from the administration only by joint and militant demonstrations. Their efforts led naturally to the building of the Artists’ Union7

Others were less apt to pay compliments to these tactics, or to the Artists’ Union. Olin Dows, an artist and the director of Treasury Relief Art Project (TRAP), believed the actions were counterproductive: “It was grotesque and an anomaly to have artists unionized against a government which for the first time in its history was doing something about them professionally.”8 And Audrey McMahon, head of the New York City Art Project, argued that the Artists’ Union, along with other radical art groups, tarnished the image of the entire WPA-FAP, for it led the public and conservative members of the government to see all artists as radicals.9 But, the Artists’ Union represented the workers’ perspective, not management’s. They held little faith in the sincerity of government bureaucrats and believed that it was the artists’ ability to organize that had led to artists being included in the WPA programs in the first place.

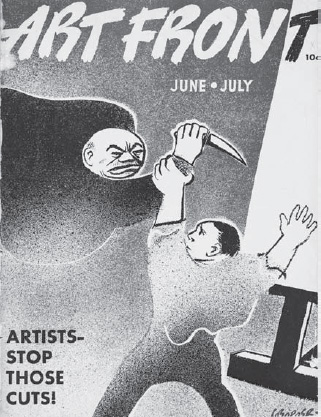

Art Front (cover), June/July 1937, (Ben Shahn papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution)

Rental Policies, Ambulances, and Solidarity Actions

Other campaigns and solidarity actions also defined the Artists’ Union’s efforts. The Artists’ Committee of Action—a loose confederation of artists that was aligned with the Artists’ Union and had been initially created in opposition to the destruction of Diego Rivera’s mural at Rockefeller Center—led the call for Mayor LaGuardia to establish a city-funded, artist-run Municipal Art Gallery and Center in New York City. LaGuardia backed the idea, and on January 6, 1936, a municipal gallery was opened at 62 West Fifty-Third Street. However, two provisions irked Artists’ Union members. First was an “alien” clause that prohibited foreign-born artists from exhibiting. The second was a clause that prohibited art that “might offend the administration” from being exhibited.10 In response, Artists’ Union members threatened to withhold their work if the two clauses were not removed, and the LaGuardia administration, not wishing to generate negative press, relented.

Not content with this success, the Artists’ Union called for an expansion of the Municipal Art Center in an article published in Art Front. The Artists’ Union envisioned an additional building where a “Circulation Library could be maintained for the rental of art works, paintings sculptures, etc., to institutions and private individuals, at a rental payable to the artists.”11 They also envisioned that this space could house a free public art school that could double as a lecture space to help popularize visual art. Lastly, they envisioned the New York Municipal Art Center as a model that could be duplicated:

The artists of New York made a good beginning. Let it be an incentive to all artists throughout the land. Build Municipal Art Centers in every city in the U.S.A.!12

Municipal art centers were not established across the country, but other campaigns that the Artists’ Union advocated for saw modest gains. The American Society of Painters and Gravers (ASPG), the Artists’ Union, and the American Group led the charge for a rental policy whereby artists would receive a small fee for exhibiting their work in museum shows—1 percent per month of the price of the work with a $1,000 maximum and a $100 minimum. Einar Heiberg of the Minnesota Artists’ Union reasoned:

Should a group of musicians play without recompense, for instance, simply because a hall had been provided? Should a singer give a program without remuneration simply because of the donation of a stage and possibly an accompanist? The artists felt there was no logic in the protests of the museum directors, and felt there was as much value in a given work of art as there might be in an orchestration, or a song, or a dental extraction. Prestige acquired from the hanging of a picture might bring the artists a lot of pretty words and some encouragement, but very few groceries.13

Many museums immediately rejected the idea as preposterous, arguing that it lacked a precedent and insisting that artists should be thankful for the exposure and the prestige of showing within their halls. Some even threatened to stop showing contemporary art if the rental fee was insisted upon, but artists held their ground. They urged artists to refuse to show in museums that did not pay the fee. Chet La More wrote in the January 1937 issue of Art Front:

Important national exhibitions have been badly dented by refusals to show. In Baltimore the 1936 Maryland Annual was reduced to a farce by the boycott. In Minnesota important concessions have been won regarding local exhibitions and in St. Louis the artists carried out a splendid public campaign, refusing to show, picketing the Museum, and running a counter exhibition.14

These nationally coordinated campaigns signified just how organized artists were in the 1930s and how successful they were in defending their rights to employment, but this should not confuse the fact that these same artists also rallied behind the economic rights of other workers. Joseph Solman explains:

The Artists’ Union and the National Maritime Union (NMU) were two of the most active participants in aiding striking picket lines anywhere in New York City. If the salesgirls went out on strike at May’s department store in Brooklyn a grouping from the above-mentioned unions was bound to swell the picket lines. I recall some of our own demonstrations to get artists back on the job after a number of pink dismissal slips had been given out. At such times everyone was in jeopardy. Suddenly from nowhere a truckload of NMU workers would appear and jump out onto the sidewalk to join our procession.15

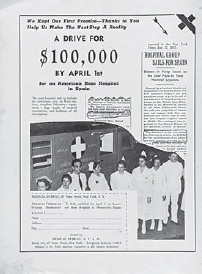

Other solidarity actions looked overseas. The Artists’ Union raised $659.27, along with food and clothing donations, that were sent to two organizations allied with the Loyalist cause during the Spanish Civil War: the Spanish Anti-Fascist Committee and Labor’s Red Cross for Spain.16 More impressive, the Artists’ Union sent two fully equipped ambulances to Spain as part of the Artists and Writers Ambulance Corp (under the sponsorship of the Medical Bureau of the American Friends of Spain) that aided the Loyalists in their fight against the Nationalists and General Franco.17 All told, the Corp was comprised of twenty ambulances, fifteen surgeons, forty-five nurses, and medical supplies.18

Advertisement in Art Front, March 1937, (Ben Shahn papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution)

Some Artists’ Union members also volunteered to fight. Paul Block, who had led the December occupation of the New York WPA-FAP administration offices, became one of 2,800 Americans who traveled to Spain and joined the International Brigades. These U.S. volunteers formed several combat battalions and noncombat units (medical and transportation) and became collectively known as the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. Block, himself, became a commander, and was killed in action in 1937 in Belchite, Spain, while leading the Lincoln Brigade’s 3rd Company into battle.19 Block’s sacrifice was not unique. Thirty-five members of the national Artists’ Union went to Spain and served as ambulance drivers or soldiers, and half of them were killed during the war.20

Artists and Organized Labor

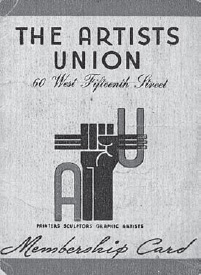

Solidarity actions defined the ethos of the Artists’ Union. The coalition of artists did not view themselves as acting in isolation: members largely self-identified themselves as workers who were part of the labor movement. The Artists’ Union logo made this clear. Centered between the “A” and “U” was a clenched fist that held the “U” for union, as if it were to be branded with an iron implement. This design showcased the Artists’ Union’s commitment to militant struggle and their emerging commitment to organized labor.

Their writings in Art Front did as well. Meyer Schapiro wrote in the November 1936 issue that artists needed to win over the support of other workers if they expected to win their own demands:

It is necessary then, if workers are to lend their strength to the artists in the demand for a government-supported public art, that the artists present a program for a public art which will reach the masses of people. It is necessary that the artists show their solidarity with the workers both in their support of the workers’ demand and in their art. If they produce simply pictures to decorate the offices of municipal and state officials, if they serve the governmental demagogy by decorating institutions courted by the present regime, then their art has little interest to workers. But if in collaboration with working class groups, with union clubs, cooperatives, and schools . . . then they will win the backing of the workers.21

Artists’ Union membership card, (Harry Gottlieb papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution)

This concept of visualizing the concerns of labor took root in the Artists’ Union. Clarence Weinstock wrote in the December 1936 issue of Art Front that Artists’ Union members had begun reaching out to other unions and asking trade unionists about what types of images they wished to see exhibited at their headquarters. The Artists’ Union, under the subcommittee Public Use of Art Committee, received numerous responses. Weinstock explains:

The International Ladies Garment Workers Unions suggests five groups of subjects: emigration of garment workers from Europe in the 1890’s and 1900’s; working conditions in the garment industry at that time—the sweatshops; the fire which led to the dressmakers’ strike of 1905 . . .

The Transport Workers Union wants: the history of transportation in New York City: the history of the union . . . scenes in the steel industry; the Irish transport strike of 1911–13 . . .

The Union of Dining Car Employees needs works showing the effect of speedup on dining car employees; the battle for union recognition on the Santa Fe . . . exploitation of women employed in hotel dining rooms and kitchens; anti-lynching subjects . . . Negro discrimination. . . .

The Amalgamated Housing Corporation of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers’ Unions suggests a series showing how New Yorkers live and the contrast of life under a system of profit economy with that under a cooperative economic system.22

Other requests came in from the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the Musicians’ Local 802, and the Bricklayers’ Local 37, among others. Here, the Artists’ Union placed their efforts in the service of working-class movements, but other writings in Art Front situated the Artists’ Union as not just in solidarity with organized labor, but as part of the movement itself. The June 1936 issue of Art Front included a report-back from the Artists’ Union eastern district convention that read, in part:

Artists’ Unions should cooperate locally with the A.F. of L. on all possible measures. Affiliation will have to pend the formation of National Organization. As the building trades are opposed to the artists, while the other unions such as musicians and teachers and bookeepers [sic], etc. favor us, it is probable our best opportunity is through the Committee for Industrial Organization (Lewis). We will only enter on the basis that we maintain our own jurisdiction.23

The Artists’ Union first became affiliated with organized labor when they voted to apply for a charter with the American Federation of Labor (AFL) in 1935 and the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in 1937. Yet because the Artists’ Union had fewer than two thousand members, the majority of whom were based in New York City, they could not become a national charter, so they merged with a CIO local—the United Office and Professional Workers of America (UOPWA)—that was comprised of bookkeepers, stenographers, office workers, and insurance agents. In December 1937, Philip Evergood, the Artists’ Union president, announced that the Artists’ Union would be renamed the United American Artists–Local 60 and it was here that the concept of “artist as worker” became most realized.

Both advantages and disadvantages came with this merger. The artists within Local 60 had the backing of a strong union, but they lost much of their independence, which affected their militancy. The UOPWA placed the artists within a drab office space and suggested that meetings be held monthly, instead of weekly. UOPWA president Lewis Merrill demanded that the Artists’ Union drop their clenched-fist logo, along with the red banners that they used in street demonstrations.24 These calls from above curtailed the artists’ creativity and signified how Merrill had completely failed to understand how artists worked or how their skill set could aid the broader labor movement.

The artists in the AU also had other adversaries. Their primary employer—the federal government—had cut the majority of artists’ positions by 1939, sending artists back to the ranks of the unemployed. Lacking hope for permanent federal patronage, Merrill advocated in 1942 that artists should seek out work in private industries. This failed to materialize in any substantial way, and later that year the United American Artists–Local 60 disaffiliated from the UOPWA, ending the artists’ formal association with labor and ending much of the activity of what had been the Artists’ Union. Left behind, however, was a legacy of one of the most successful groups to ever organize large numbers of artists around economic issues—one that became closely aligned with organized labor instead of isolated in a hermetic art scene. The Artists’ Union signified a brief era when visual artists realized their collective power, and one where artists identified themselves as workers.