Resistance or Loyalty: The Visual Politics of Miné Okubo

IN 1939, MINÉ OKUBO was studying art in Europe on a University of California–Berkeley scholarship when she faced a terrible predicament—how to escape a war zone. England and France had declared war on fascist Germany, and Okubo managed to flee, taking the last passenger boat from France back to the United States. Safe at home, she went to work painting murals for the Works Progress Administration–Federal Art Project (WPA-FAP). However, she had inadvertently returned to another war zone. The Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941, shattering any sense of normalcy in the United States.

Days after the attack on U.S. soil, Okubo’s father was taken into custody by the FBI and held without charges. Thousands of other Japanese Americans—primarily community leaders, fishermen, and newspaper editors—would also be apprehended.1 In the weeks and months to follow, a curfew was established from eight p.m. to six a.m. for Japanese Americans on the West Coast and Hawaii. Bank accounts were frozen and individuals could not travel outside a five-mile radius of their home—an order that was initiated to prevent “possible” future attacks.

The federal government and the media depicted Japanese Americans as an enemy within. Lt. Gen. John L. DeWitt, head of the Western Defense Command, said:

In the war in which we are now engaged racial affinities are not severed by migration. The Japanese race is an enemy race and while many second and third generation Japanese born on United States soil, possessed of United States citizenship, have become “Americanized,” the racial strains are undiluted. . . . It, therefore, follows that along the vital Pacific Coast over 112,000 potential enemies, of Japanese extraction, are at large today.”2

DeWitt’s recommendation to the Roosevelt administration was that all Japanese Americans and Japanese aliens on the West Coast and Hawaii should be apprehended and placed into wartime concentration camps. His paranoia was met with skepticism.

Attorney General Francis Biddle wrote a memo to President Franklin D. Roosevelt opposing DeWitt’s call for evacuation. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover also concluded that internment camps could not be justified for security reasons and there was little to no evidence to support the claim that Japanese Americans were aiding the Japanese emperor.

Nonetheless, the media beat the drum of wartime hysteria and racial profiling. The Los Angeles Times editorialized, “A viper is nonetheless a viper wherever the egg is hatched—so a Japanese American, born of Japanese parents—grows up to be a Japanese, not an American.”3 By March of 1942, a national survey found that 93 percent of Americans approved of internment camps for Japanese aliens, and 59 percent favored the internment of Japanese Americans.4 Dissenting voices—apart from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU)—were few and far between.

President Roosevelt, however, had the final word. On February 19, 1942, he signed Executive Order 9066, allowing the secretary of war to prescribe military areas where “the right of any person to enter, remain in, or leave shall be subject to whatever restrictions the Secretary of War or the appropriate Military Commander may impose in his discretion.”5 In essence, Roosevelt allowed DeWitt and the U.S. military to strip Japanese Americans of their citizen rights, due process, and their civil liberties.

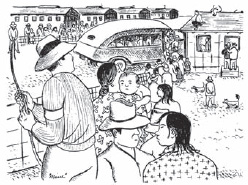

Miné Okubo, “Waiting for Military Police Bus with Personal Belongings,” Citizen 13660 (courtesy of Miné Okubo Estate)

The evacuation process began promptly after Roosevelt’s signature. Japanese American communities were often given just a matter of days to report to assembly centers, forcing them to lose everything—homes, businesses, farms, possessions, and careers. Despite no evidence of wrongdoing, more than 110,000 Japanese Americans, nearly two-thirds of whom were American citizens, were sent to assembly centers and then to wartime concentration camps run by the War Relocation Authority (WRA).6

On May 1, 1942, Okubo and her brother, Toku, were sent to the Tanforan Assembly Center in San Bruno, just south of San Francisco. Other family members were sent to different camps. As they boarded the buses, they wore tags that reduced their family name to a number: 13660.

Throughout her time in the camps—at Tanforan and later at the Topaz concentration camp in Utah—Okubo produced more than two thousand sketchbook drawings with a specific audience in mind: “Being an artist, I decided to record my whole camp experience. I had many, many friends on the outside and I thought this would be a good way to repay them for their kindness in sending letters and food packages and telling us that we were not forgotten.”7 Okubo’s audience would also extend beyond her immediate friends. She published her drawings in the Topaz Times (the official camp paper) and Trek (an arts and literary publication produced by internees at the Topaz camp) that reached the internee population. Most notably, she reached a mass audience when Citizen 13660, her personal narrative about her camp experience, was published in 1946, shortly after the end of the war and her January 1944 release.

Citizen 13660 told Okubo’s story, but it also performed another important function. It helped counter the government’s sanitized version of the wartime concentration camps. The U.S. government had attempted to control the public image and memory of the camps by depicting them as places free of hardship, where Japanese Americans were enjoying a “pioneer” lifestyle in the western lands of the United States.8 Okubo told a different story—images and text about internees living behind barbed wire and guard towers, in extreme weather conditions, where sorrow, boredom, and anxiety were commonplace. She also documented stories of survival and perseverance—internees adapting to the harsh environment, making do, and creating community and culture within a concentration camp. She documented the human spirit and captured the humor, creativity, and ingenuity of thousands of people confined within a one-mile radius.

Significantly, Citizen 13660 was not a “history” of Tanforan and Topaz. It was Okubo’s personal narrative of her experience during wartime—one that tells the story of an ordinary citizen who, at age thirty, found herself confined within a camp. Okubo was not an activist or an organizer when she was imprisoned. She was a passive observer and a model prisoner. Her drawings and text critiqued the internees who organized and spoke out as much as they critiqued the racist federal policy that had created the camps. Citizen 13660 presents an odd, but compelling, case for the role of art within movements and in recording history—especially a history that the U.S. government did not care to broadcast. Her images and text directly challenge the historical amnesia and the control of the images of the internment camps by the federal government. Okubo also obscures aspects of the internment history itself by giving little attention to the actual resistance that took place in the camps, leaving readers with an incomplete, yet still important, portrait of camp life.

Tanforan

Okubo’s Citizen 13660 presents a chronological timeline of her wartime experience—one that guides the reader from her travels through Europe during the fall of 1939 to Berkeley to the Tanforan Assembly Center, and finally to her imprisonment at the Topaz wartime concentration camp. In nearly every image, Okubo is present in the picture plane acting as a guide, either as the central figure or standing on the edge of the frame, showing the viewer what she herself was looking at. A good example is a drawing of the first time she entered her “living quarters” at Tanforan. Okubo places herself at the far left of the page, looking into two small rooms that had recently housed horses at the racetrack-turned-prison. Okubo cuts away the wall of “stall 50” so the viewer can see the poorly constructed room in its entirety. By presenting herself in each image, she encourages the viewer to empathize with her situation, and she presents herself as both a participant and observer.9

Miné Okubo, “First View of Stall 50 at Tanforan,” Citizen 13660 (courtesy of Miné Okubo Estate)

This was a political act. Okubo’s self-positioning says, “I can’t believe this is happening to me,” as well as, “This should not be happening to me,” thus defending her rights to American citizenship. But Okubo presents herself as more than just a citizen; she presents herself as an artist.

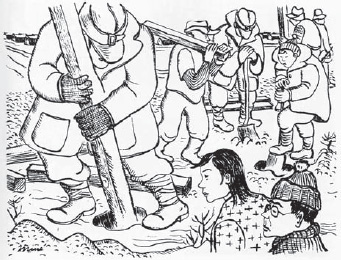

Miné Okubo, “Army Inspection at Tanforan,” Citizen 13660 (courtesy of Miné Okubo Estate)

In one image, Okubo documents the Army conducting a routine search of the barracks for contraband, a list that included weapons, ammunition, shortwave radios, Japanese literature, and cameras.

She shows us an inspector studying one of her letters as a military policeman stands guard. Okubo sits on the bed and presents herself as a naïve, childlike artist cutting paper with a scissors. Around her is her art: paper streamers hang from the ceiling, a paper hat coiled like a snake is on her head, a cut-out animal sculpture sits on the floor, and an overly simplistic drawing of a horse hangs on the wall. Significantly, the drawings and sculptures that she presents in her room were not representative of her illustrative style or chosen subject matter that formed the basis of Citizen 13660. Neither were they like the sophisticated illustrations that she would later do for the Topaz Times or Trek.

Instead, Okubo seems to be playing a trick on the inspectors, making them believe that she (and by extension her art) was harmless and not worthy of their attention. Her approach paid off, for none of her drawings were confiscated, and neither was she ever reprimanded. Whether this was due to the content and style of Okubo’s images or the military police failing to see anything subversive in her work is unknown. What is clear is that Okubo was free to sketch throughout Tanforan and the next internment camp that she and her brother were sent to: Topaz.

Pro-Japanese or Pro-Administration

“After being uprooted, everything seemed ridiculous, insane, and stupid. There we were in an unfinished camp, with snow and cold. The evacuees helped sheetrock the walls for warmth and built the barbed wire fence to fence themselves in. We had to sing ‘God Bless America’ many times with a flag. Guards all around with shotguns, you’re not going to walk out. I mean . . . what could you do? . . . I tried to make the best of it, just adapt and adjust.”

—Miné Okubo10

At Topaz, Okubo found herself in a barren, hostile environment of high winds, little vegetation, and alkaline dust that covered everything in sight, including the ten thousand internees who were crammed into one square mile comprised of forty-two blocks of housing barracks, mess halls, and administration buildings. When she arrived, she was handed a copy of the Topaz Times that described Topaz as the “Jewel of Utah.”

Okubo’s drawings depict these hardships. One visualizes internees hard at work, putting up the very wires and posts that would keep them fenced in.

Miné Okubo, “Evacuees Fencing Themselves in at Topaz,” Citizen 13660 (courtesy of Miné Okubo Estate)

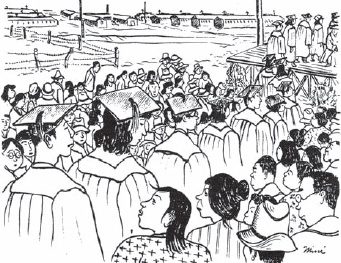

Another shows her and her brother scavenging late at night, and against camp rules, for materials to build rudimentary furniture for their room. Another drawing, created near the end of her imprisonment, depicts a high school graduation ceremony. Lacking are any signs of joy that one might associate with a celebration marking an important life achievement. Okubo depicts the graduates with serious expressions—some downcast—and is careful to document the barbed-wire fences and the housing barracks in the background, informing her readers that these were high school graduates behind bars.

Yet even within this image it is difficult to know what Okubo is really thinking about the scene and the circumstances that she documents. Elena Tajima Creef writes: “Throughout the pages of Citizen 13660, we are allowed a glimpse of the personal and the public spaces inside the camp, but we are never allowed any such glimpse into the private space of Okubo’s interior self. . . . Okubo never shows or tells us what she is actually feeling; instead, she gives us a brilliantly detailed—though somewhat detached—record of the internment experience.”11

Miné Okubo, “Topaz High School Graduation,” Citizen 13660 (courtesy of Miné Okubo Estate)

However, readers of Citizen 13660 can make assumptions about Okubo’s thought process through the topics that she omits or those she pays minimal attention to. Page after page depict her and other internees resisting the harsh elements of the Utah desert, but few images depict people resisting the actual internment process itself. And when she does depict people resisting, she criticizes rather than supports them.

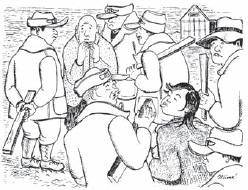

For example, one of her images from Topaz depicts her railing against an older male prisoner who was attempting to organize other prisoners against the government’s “loyalty” questionnaire and the call for male internees to register for the armed services. In this image, Okubo sticks her tongue out at the organizer and the group of men that gathers near him. Her text reads, “Strongly pro-Japanese leaders in the camp won over the fence-sitters and tried to intimidate the rest. In the end, however, everyone registered.”12

Here, Okubo greatly oversimplifies the matter and places the organizer in the role of the antagonist. She labels him as “Pro-Japanese”—akin to the “enemy”—and presents him as a troublemaker, someone whose efforts are detrimental to the other internees. Her position was not unique; a political divide did exist within the camp, especially between the Nisei (children born to Japanese people in a new country) and the Issei (first-generation immigrants from Japan). Scholar Laura Card writes that officers of the Nisei-led Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) urged cooperation with the government—including turning in dissenters—as well as peaceful acceptance of internment. They felt that cooperation was necessary to dispel any stereotypes of disloyalty and “mitigate the present circumstances and perhaps have a lien on better treatment later.”13 Okubo chose the route of cooperation, raising questions about how resistant her artwork was compared to those who put much more on the line. Individuals who spoke out and organized against their imprisonment, the “loyalty” tests, and registration into the armed forces risked being sent to other camps, physical violence, and even death.14 Okubo, by contrast, risked very little by quietly documenting her displeasure with the camps in a book that was published after her release. Her chosen tactic was to “adapt and adjust,” but she does a disservice to those who did organize by either not telling their stories or by stereotyping them simply as “Pro-Japanese” and disloyal, for their position was far more complex than she allows her readers to see.

Miné Okubo, “Okubo Reaction to ‘Pro-Japanese’ Camp Leaders,” Citizen 13660 (courtesy of Miné Okubo Estate)

Organized Resistance

Other stories and experiences by internees fill in the gaps missing in Okubo’s text. During the evacuation order, Minoru Yasui (Oregon), Fred Korematsu (California) and Gordon Hirabayashi (Washington) all refused to leave their homes, stating that Roosevelt’s order was unconstitutional. The three individuals filed a lawsuit and took their case all the way to the Supreme Court, which sided against them in Hirabayashi v. United States (1943), Yasui v. United States (1944), and Korematsu v. United States (1944)15 In the assembly centers and the ten wartime concentration camps, resistance was omnipresent, particularly during the summer of 1943. This was when internees were forced to fill out a questionnaire that tested their “loyalty.” For example, question 27 was directed at draft-age males and asked, “Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the US or combat duty, wherever ordered?” Question 28 was directed to all internees: “Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faith-fully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, or any other foreign government, power, or organization?”16 This created a serious predicament for nearly one-third of all residents in the camps. Heather Fryer explains that it “asked non citizens to renounce all ties of loyalty to the Empire of Japan. Ineligible for citizenship in the United States, these older Japanese were asked to make themselves stateless in order to regain their freedom.”17

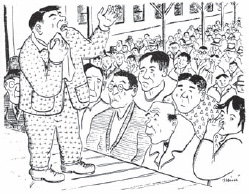

Miné Okubo, “Topaz Meeting In Response to Loyalty Tests,” Citizen 13660 (courtesy of Miné Okubo Estate)

The results of the questionnaire had profound consequences. Those who answered “yes” were slowly released and resettled predominantly in the Midwest and Northeast. Those who answered “no” were sent to the Tule Lake camp in California. Close to 1,300 detainees, one-tenth of all Topaz residents, were sent to Tule Lake during the fall of 1943. Included were all those who said they wished to return to Japan along with the “no-no’s”—those who were given a second chance to change their answers to the questionnaire but refused to do so. Family members wishing to stay together also were sent to Tule Lake. Okubo reduces this epic moment at Topaz to a handful of pages. She shows outright disdain toward those who resisted the questionnaire and those who resisted joining the military. In one key image, she depicts an all-male audience—older internees (presumably a large percentage of whom were Issei)—listening to a camp organizer in a meeting space. The speaker and the audiences are upset and crying and Okubo depicts herself holding her nose in disgust. Her text reads, “Center-wide meetings were held, and the anti-administration rabble rousers skillfully fanned the misunderstandings.”18 Here, she again casts organizers in a negative light and grossly oversimplifies them as disloyal—that is, “anti-administration rabble rousers.”

Consider the case of Frank Emi, who was imprisoned at the Heart Mountain Internment Camp in Wyoming. Emi, much like those interned at Topaz, spoke out against the questionnaire. He posted his questionnaire on the camp’s mess-hall doors with a handwritten message that read: “Under the present conditions and circumstances, I am unable to answer these questions.”19 This act of resistance was not isolated. Kiyoshi Okamoto, a California high school teacher and former soil tester in Hawaii, became a leader in Heart Mountain against unjust and racist policies. He gave a speech during a mass meeting and urged Nisei to stand up for their rights as U.S. citizens. He then taught those in attendance about their constitutional rights. Together, Okamoto, Emi, and others helped form the Fair Play Committee (FPC), which declared that internees would not cooperate with the draft unless their citizenship rights were honored first. More than four hundred Nisei attended the meetings; the group had two hundred dues-paying members, and three hundred FPC members refused to be drafted.

Camp administrators responded by going after the leadership. Emi and six other leaders of the FPC at Heart Mountain were arrested and “indicted for conspiracy to violate the Selective Service Act and for counseling others to resist the draft.”20 In court, Emi continued to speak out:

Miné Okubo, (map) Trek, Vol. 1, No. 2 February 1943, Central Utah Relocation Center, Project Reports Division, Historical Section, Special Collections and Archives, Topaz Internment Camp Documents, 1942-1943 (MSS COLL 170) (Utah State University Merrill-Cazier Library, courtesy of Miné Okubo Estate)

We, the members and other leaders of the FPC are not afraid to go to war—we are not afraid to risk our lives for our country. . . . We would gladly sacrifice our lives to protect and uphold the principles and ideals of our country as set forth in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, for on its inviolability depends the freedom, liberty, justice, and protection of all people including Japanese-Americans and all other minority groups.”21

His courageous act of resistance led to him and six other FPC leaders being sentenced to four years at Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary in Kansas. They were housed with the general population, considered criminals for refusing to fight for a government that had placed them in concentration camps without due process. After the war, an appeals court overturned their conviction and President Truman granted a presidential pardon on December 24, 1947, to all draft resisters, including the Nisei.

However, Okubo chastised similar individuals who organized at Tanforan and Topaz. Her text following the loyalty questions at Topaz is instructive. She notes “the ‘disloyal’ were finally weeded out for eventual segregation.”22 She adds in a later illustration, “The program of segregation was now instituted. One of its purposes was to protect loyal Japanese Americans from the continuing threats of pro-Japanese agitators.”23 And she comments on the “loyal” internees who were transferred from another camp to Topaz: “Twelve hundred loyal citizens and aliens were transferred from Tule Lake to Topaz. Their arrival once more brought excitement to our now relatively peaceful city.”24

Miné Okubo, “Evacuees Arrives from Tule Lake,” Citizen 13660 (courtesy of Miné Okubo Estate)

At the same time, she devoted only two pages to the murder of sixty-three-year-old James Wakasa, who was shot in the chest and killed when he walked too close to the barbed-wire fence that defined the perimeter of the camp. Instead, her drawings focuses on the women who made paper wreaths for his funeral—a passive response that documents the chain of events but offers up little critique when it was needed.

Visual Testimony

Okubo was rewarded for her decision not to agitate those who controlled her freedom. She, along with all the other internees who answered “yes” to the key questions on the loyalty tests were slowly transitioned out of the camps. Okubo herself was given the opportunity to leave Topaz in 1943, but she decided to stay until January 1944 to finish her sketches of camp life before moving to NYC for an illustration job. Fortune magazine had seen her illustrations in Trek and offered her the chance to illustrate their special issue on Japan. The publication wanted Okubo to shine a light on the internment experience, and the WRA was not only aware of her new opportunity but also approved of it. Each internee who left the camp had to provide the WRA with references (be it their new landlords, employers, or education programs), and all references were carefully screened. Greg Robinson argues that this process indicates that the WRA promoted Okubo’s work and viewed it as beneficial, for it aligned with their new objectives to reintegrate Japanese Americans back into society.25 Many Japanese Americans were dissuaded from returning to their homes on the West Coast, and were sent to the East Coast instead. Again, Okubo is remarkably subdued with regard to this gross injustice. In her introduction for the 1983 reprinting of Citizen 13660, she writes, “For the Nisei, evacuation had opened the doors of the world. After the war, they no longer had to return to the Little Tokyos of their parents. The evacuation and the war had proved their loyalty to the United States.”26

Miné Okubo, “Women Creating Paper Floral Wreaths for Funeral,” Citizen 13660 (courtesy of Miné Okubo Estate)

Okubo’s quote epitomizes the ironies and contradictions that surround her work. She both criticizes and compliments federal internment policy. Moreover, she both exposes and obscures this history. Her perspective on how the camps personally affected her is equally mixed. She states that it was positive from a creative standpoint. “I am not bitter. Evacuation had been a great experience for me because I love people and my interest is people. It gave me the chance to study human beings from cradle to grave, when they were all reduced to one status.”27 Yet, she also writes that the internment camps were a “tragic episode” and that “some form of reparation and an apology are due to all those who were evacuated and interned.”28

This stance is admirable, but her critique came late. Okubo’s drawings and writing were not outspoken against WRA policy in the 1940s. That said, it was dangerous to be outspoken, considering that Okubo was a prisoner and she had no way of knowing when or if she would be released. Thus understanding her text first and foremost as a prison memoir is important—that by simply detailing her experiences she shined a negative light on the policy of the federal government. Additionally, her text became more influential as the decades passed, for it introduced the chilling history of the internment camps to a new generation of readers, ones who knew little to nothing about the camps’ existence.

And despite the shortcomings of Okubo’s text that demonstrated little solidarity with other internees whose politics differed from hers, she nevertheless told her story and did so in a manner that was accessible and allowed readers to empathize with her situation. In doing so, she opened up a host of questions, including how one defines resistance. Certainly Okubo was not engaged in the “resistance” in the camps if we define resistance through an activist perspective of organizing and directly challenging power. But her book did expose the history of internment camps to a large audience. Her images and text acted as a call for never again—a stance that she echoed in a 1983 interview: “I am a creative, aware person . . . an observer and reporter. I am recording what happens, so others can see and so this may not happen to others.”29 Throughout her adult life, Okubo continued to tell the story of the internment camps through interviews, illustrations, and testimonies. In 1981, she testified before the United States Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Citizens at the New York City hearing. Okubo stressed the need for the public to be informed about the history of the camps and, to close her testimony, she presented the Commission with visual evidence—a copy of her book, Citizen 13660.