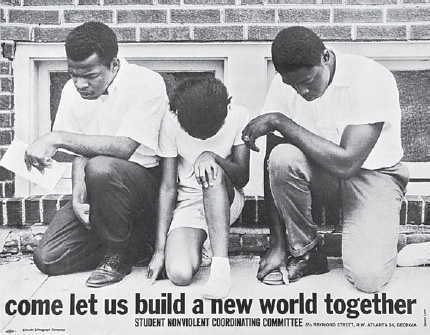

Come Let Us Build a New World Together

IN MID-JULY 1962, DANNY LYON had just finished his junior year at the University of Chicago, studying photography and history, when he decided to hitchhike south 390 miles from Chicago to Cairo, Illinois. A friend in Chicago had been arrested in Cairo while demonstrating against segregation, and Lyon wanted to see the emerging civil rights movement for himself. He brought with him a Nikon F camera, film, and the name of a contact person.

In Cairo, Lyon’s contact brought him to a community-organizing meeting, where he heard Charles Koen, a sixteen-year-old high school student and leader in the Cairo Nonviolent Freedom Committee, address a small crowd. He also heard John Lewis speak. Lewis was a student leader of the Nashville lunch-counter sit-in movement and the Freedom Rides and had joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in June, a month prior, as a field secretary. Following the speeches, Lewis and Koen led the group to the city’s only public swimming pool—one that was still segregated, despite a state mandate demanding otherwise. Lyon recalls:

There was no press . . . no film cameras, no police, and no reporters. I had my camera, and I ran along as this brave little group marched through the sunlit and mostly empty streets of a very small American town. With the exception of a few young black men, everyone else who was watching seemed to hate and deride the demonstrators, many of whom were children.1

When the group arrived at the pool, they stopped outside the building and prayed. Afterward, the group went into the middle of the street and sang. The peaceful demonstration was ruptured when a white man drove his pickup truck at the crowd. Everyone stepped aside, except for a thirteen-year-old African American girl, who stood her ground, refused to move, and was knocked down by the truck.

Lyon’s signature photograph of the day featured this thirteen-year-old girl kneeling down in prayer with Lewis to her left and Koen to her right. A year later, SNCC printed ten thousand copies of the image as a poster with text that read COME LET US BUILD A NEW WORLD TOGETHER. Posters sold for $1 and helped raise much-needed funds.2

SNCC poster, Come Let Us Build a New World Together, 1962, photograph by Danny Lyon (copyright Danny Lyon/Magnum Photos; image reproduction: Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan)

SNCC chose Lyon’s image for good reason. It documented themselves (student activists) and their chosen tactics for the movement (nonviolent direct action.) The text of the poster was an invitation and recruitment pitch, pulling activists into the movement. For Lyon, the photograph signified day one of a two-year journey that would send him across the far expanses of the South, working as a white artist within a black-led movement to end segregation and racial discrimination.

![]()

SNCC was the most radical of the Southern civil rights organizations, one that began as a student group and evolved into a cadre of full-time organizers.3 SNCC focused on direct-action campaigns and embedded itself in rural communities of the Deep South and for months, if not years, engaged in long-term campaigns that sought to develop and support local leaders.4 This work was exceedingly dangerous, for it existed outside the gaze and the protection of the mass media that typically added a certain level of safety from violence as perpetrators sought to keep their most heinous acts out of sight. Thus, SNCC, by necessity and by its own ingenuity, had to create media to provide protection and document its work on the ground. Mary King, SNCC communications secretary, stated, “It is no accident that SNCC workers have learned that if our story is to be told, we will have to write it and photograph it and disseminate it ourselves.”5

When SNCC was first launched in 1960, three administrative departments were established at the Atlanta office: coordination, communications, and finance. SNCC director of communications Julian Bond and his staff worked around the clock, sending out press releases to media contacts across the country. They also edited the monthly SNCC newsletter The Student Voice, produced promotional materials, printed posters, and created other forms of ephemera. All of this work was dependent on field reports.

In 1962, Bond issued a twelve-point internal memo to SNCC workers in the field:

It is absolutely necessary that the Atlanta office know at all times what is happening in your direct area. When action starts, the Atlanta office must be informed regularly by telephone or air mail special delivery letter so that we can issue the proper information for the press. (Atlanta has the two largest dailies in the South; we have contacts with the New York Times, Newsweek, UPI, and AP, the two wire services; we have a press list of 350 newspapers, both national and international).6

Bond added:

Please delegate one or two people to take photographs of the action. If you have facilities to develop films immediately where you are, have the pictures developed and send the shots to us. If there are no facilities, send the roll(s) of film to us in manila envelopes air mail special delivery addressed personally to James Forman or Julian Bond, along with descriptions of what the photographs are about.7

The Atlanta office did the rest, disseminating the images to the nation and the world.

![]()

Danny Lyon’s introductory experience in Cairo had propelled him to head farther south in August—to the SNCC office in Atlanta. The only problem was that when he arrived, the office was empty. The entire staff was in Albany, Georgia, another 150 miles south. When he finally located SNCC workers in Albany, he met James Forman, executive secretary of SNCC, for the first time. Lyon recalls:

Forman treated me like he treated most newcomers. He put me to work. “You got a camera? Go inside the courthouse. Down at the back they have a big water cooler for whites and next to it a little bowl for Negroes. Go in there and take a picture of that.”8

Back in Atlanta a darkroom was set up in the closet of the SNCC office, and Lyon was given a credit card for air travel, allowing him to rush to hot spots across the South at a moment’s notice.

With Forman’s blessing, I had found a place in the civil rights movement that I would occupy for the next two years. James Forman would direct me, protect me, and at times fight for a place for me in the movement. He is directly responsible for my pictures existing at all.9

Forman understood the power that photographic images had on the public’s visual consciousness. He was one of a handful of civil-rights activists/leaders who carried a camera with him, a short list that included Malcolm X, Robert Zellner (SNCC), Wyatt Tee Walker (SCLC), and Andrew Young (SCLC).10 In late March 1963, one of his photographs appeared in the New York Times, exposing how local sheriffs had used police dogs to attack black demonstrators who were attempting to register to vote in Greenwood, Mississippi. Forman was arrested, but SNCC field secretary Charles McLaurin managed to wrestle his camera away from the police officer during the tussle. “Knowing that those photographs—later to be seen around the world—would get into the right hands,” reflects Forman, “was one of the biggest help to my morale in jail.”11

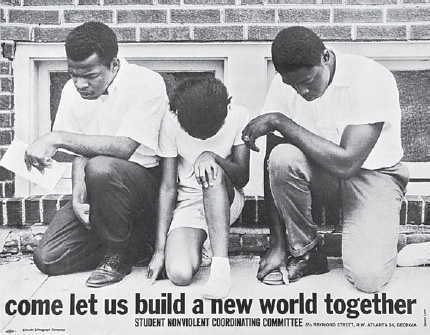

Lyon documented similar types of events in other locations, including Albany—actions with the camera in mind. When tense moments were not available, SNCC created them. “Albany was quiet when I was there, so two people went out and got arrested on my behalf. The picture of Eddie Brown, a former gang leader, being carried away by police with a look of beautiful serenity on his face was reproduced in college papers and SNCC fund-raising flyers.”12

Danny Lyon, Eddie Brown Calmly Being Carried off by the Albany Police, 1963 (from Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement, copyright Danny Lyon/Magnum Photos)

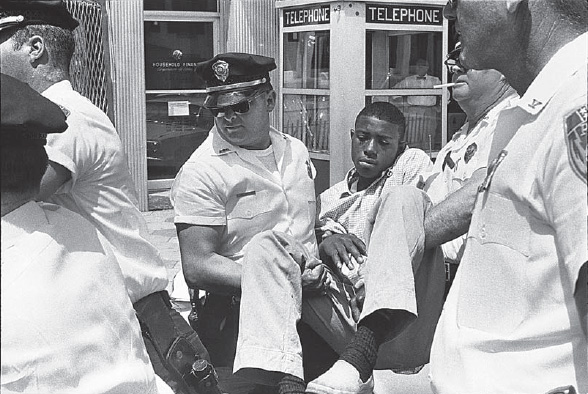

Much of Lyon’s best work took place off the beaten path. In August 1963, Lyon traveled to southwest Georgia to investigate a report that thirty-two teenage African American girls had been locked up for weeks in the county stockade outside of Leesburg. The girls had been arrested for demonstrating in Americus in July and August and were being held without charges in abysmal conditions—a single room without beds, no working sanitation facilities, and one meal allotted per day. Lyon writes, “For all practical purposes the girls, many as young as thirteen . . . had been forgotten by the world, including SNCC’s Atlanta office, which had its hands full.”13

On route to Leesburg, Lyon met up with an activist from Americus, and the two devised a plan. Lyon would hide inside the car as they approached the jailhouse. His companion would go inside and distract the lone jailer while Lyon snuck out of the car and walked behind the building to take pictures through the bars.

The plan worked. Lyon went undetected, and in a matter of days his photographs were delivered to a U.S. congressman, who promptly entered them in the Congressional Record. The uproar that followed resulted in the girls being released in early September. Lyon wrote:

Danny Lyon, Leesburg, Georgia Stockade, 1963 (from Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement, copyright Danny Lyon/Magnum Photos)

Until that moment I don’t think I had really been accepted into SNCC. After all, SNCC people were activists. Most of them went to jail routinely. They did things. It was one of their finest qualities. All I did was make pictures. But in Americus, my pictures had actually accomplished something. They had gotten people out jail.14

Lyon was being too self-critical. His photographs and those of other SNCC photographers played a prominent role in the success of the organization. Besides, SNCC photographers were not simply documentarians, they were artists and fieldworkers, entrenched in the daily work of community organizing and movement-building. Photographers had become the eyes of the civil-rights movement.

Mississippi

“When you made a move on Mississippi, one of the things you had to do was come to grips with your own mortality . . . This is not going to be big demonstrations with lots of television cameras with people around watching . . . when we went on those highways in the middle of the night . . . you had to think that you would never live to see your home again.”

—Charles McDew, SNCC15

In the summer of 1960, SNCC organizer Bob Moses toured Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana to seek out and cultivate local leaders. In Cleveland, Mississippi, he met Amzie Moore, head of the Cleveland NAACP. Moore persuaded him that the greatest asset that SNCC could provide them was to help organize a voter registration campaign. Moses agreed, and by August 1961, SNCC opened its first voter registration school in McComb, right in the heart of Klan country.16 By fall 1962, Moses was in charge of six offices and twenty field secretaries.17 He described his philosophy as such:

You dig into yourself and into the community to wage psychological warfare, you combat your own fears about beatings, shootings and possible mob violence; you stymie, by your mere physical presence, the anxious fear of the Negro community . . . you organize, pound by pound, small bands of people . . . you create a small striking force . . . The deeper the fear, the deeper the problems in the community, the longer you have to stay to convince them.18

Fear was an understatement, for violence upheld white supremacy. On June 12, 1963, Mississippi NAACP leader Medgar Evers was assassinated by a gunshot blast to his back. The year before, federal protection was required to guard James Meredith when he became the first African American to enroll at the University of Mississippi. White students rioted. Two people were killed, 160 people were injured, and 28 gunshot wounds were reported. The majority of those wounded were federal marshals.

Danny Lyon, On the Road to Yazoo City, Mississippi, 1963 (from Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement, copyright Danny Lyon/Magnum Photos)

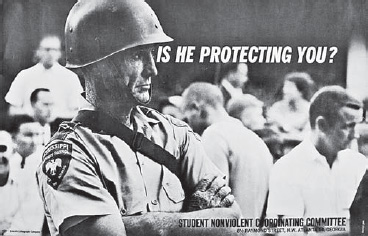

This was the climate that SNCC operated in when they chose Mississippi to be their primary location to launch a voter registration drive. SNCC offices were firebombed and SNCC workers were routinely jailed, beaten, and shot at. Some were killed. SNCC fieldworker Frank Smith stated, “There is no protection against Mississippi . . . Only the Federal government can protect us and it won’t.”19

SNCC poster, Is He Protecting You?, ca. 1963, photograph by Danny Lyon (copyright Danny Lyon/Magnum Photos; image reproduction: Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives and Radicalism Photograph Collection, Tamiment Library, New York University)

One would expect that the vast majority of photographs that SNCC took in Mississippi would have documented the extreme levels of violence and police brutality. Instead, the opposite was the case. The majority of photographs that Lyon and other SNCC photographers took were images of organizing drives and movement-building: mass meetings, literacy training workshops, canvassing, voter-registration drives, and time spent simply hanging out together.

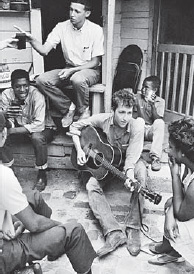

Lyon’s photographs in 1963 include, among others, an image of James Forman talking on the phone inside the Greenwood office; Bob Moses, Charles Sherrod, and Randy Battle conversing with an elderly woman on her porch during a voter-registration drive in rural Georgia; and a young Bob Dylan playing guitar behind the Greenwood office while a small crowd gathers, some listening, some talking among themselves.

What is so remarkable about these images is how ordinary the scenes are. One would never get the sense that these individuals were operating within one of the most dangerous counties in the United States. They are almost contemplative, lacking any sense of fear or violence—the antithesis of the types of photographs that mainstream media outlets were running in their coverage of the civil-rights movement. Instead, Lyon’s images project the “nit-and-grit” of daily organizing work, by the people who built the civil-rights movement.

The reality of life behind the work was quite different, of course, in a place where simply possessing a camera could lead to arrest or worse. In 1962, Lyon was arrested in Cleveland, Mississippi, for taking photographs in the street near Amzie Moore’s house. The police officer told Lyon that he had to pay $1,000 bond to be “engaged in the business of photography.”20 His final warning to Lyon after letting him go: “If I see you anywhere I’m going to kill you.”21

Danny Lyon, Bob Dylan Behind the SNCC Office, Greenwood, Mississippi, 1963 (from Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement, copyright Danny Lyon/Magnum Photos)

Lyon did not heed the police officer’s advice. He returned regularly to Mississippi throughout 1963 and 1964 and photographed SNCC activities throughout the state. In 1964, he documented SNCC’s most ambitious and controversial activity to date—the Mississippi Summer Project.

In late 1963, SNCC laid the groundwork for a summer campaign that was designed with three goals: a statewide voter-registration drive, the establishment of freedom schools throughout the state, and the formation of a new political party—the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.22

The most controversial aspect of the plan was the recruitment of 1,000 white, middle-class college students, primarily from northern states, who would fill the volunteer ranks. Many in SNCC felt that the addition of so many white volunteers would disrupt SNCC’s race and class balance. SNCC was a black-led organization, and many of its positions in Mississippi were filled by those who were native to the state and had grown up as sharecroppers. Bob Moses, the director of the Summer Project, held the final word in the matter; he would not be part of an organization that was not integrated.

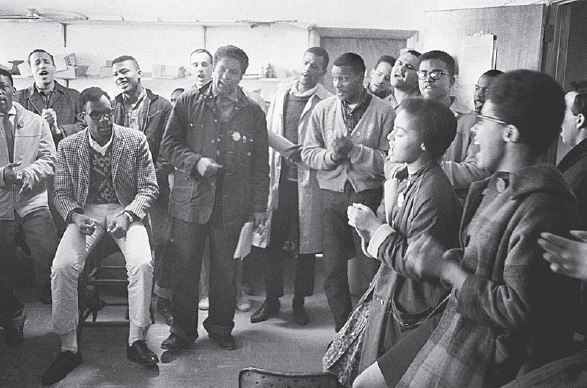

Danny Lyon, James Forman Leads Singing in the SNCC Office on Raymond Street in Atlanta, 1963 (from Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement, copyright Danny Lyon/Magnum Photos)

There were also tactical reasons for bringing in a thousand white volunteers. The mass media would scarcely cover events taking place in rural Mississippi, so SNCC reasoned that the “heated atmosphere caused by the presence of many volunteers, especially whites, would force the federal government to intervene—possibly with the use of troops.”23 Confrontation would result in media attention. Forman asserted:

White people should know the meaning of the work we were doing—they should feel some of the suffering and terror and deprivation that black people have endured. We could not bring all of white America to Mississippi. But by bringing in some of its children as volunteer workers, a new consciousness would feed back into the homes of thousands of white Americans as they worried about their sons and daughters confronting “the jungle of Mississippi,” the bigoted sheriffs, the Klan, the vicious White Citizens’ Councils.24

In early 1964, SNCC began visiting northern college campuses to recruit students. Each volunteer had his or her portrait taken and was asked to fill out a list with “names of the applicants’ Congressional representatives, the names of their college and hometown newspapers . . . organizations they belonged to . . . and ten people who would be interested in receiving information about their activities.”25

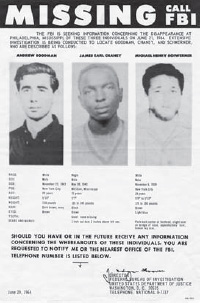

Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner, Missing, Call FBI poster (call number: Ephemera/Civil Rights/1964/Box 5, 1961–1969, MDAH Collection)

The worst possible news to report came early on. On June 21, days before many of the volunteers had arrived in Mississippi, three civil-rights workers disappeared—two affluent white college students from New York (Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman) and one black Mississippian (James Chaney). The three had been arrested by the police in Philadelphia, Mississippi, and released late at night into the waiting hands of the Klan, who worked in collusion with the local police sheriffs.

The FBI found their bodies six weeks later. Each had been shot at point-blank range. The terrible outcome and the fear that it generated might have scared away many of the summer volunteers, but the opposite occurred. It strengthened their resolve. SNCC itself grew stronger, and its work expanded.

SNCC’s emphasis on photography also grew in 1963 and 1964. Lyon was no longer the principal SNCC photographer. SNCC Photo was established and enlisted more than a dozen photographers to also document the movement. The multiracial group included black photographers Clifford Vaughs, Joffre Clark, Fred deVan, Rufus Hinton, Bon Fletcher, Julius Lester, Norris McNamara, and Francis Mitchell; the Latina photographer Mary Varela; the Japanese Canadian photographer Tamio “Tom” Wakayama; and the white photographer Dee Gorton.26 Additionally, Matt Herron, a white photojournalist from New York, organized the Southern Documentary Project, modeled after the Farm Security Administration’s (FSA) photography work in the 1930s.27 The driving concept behind the project was to document organizing activities other than demonstrations—in other words, everyday life. For a project adviser, Herron consulted with Dorothea Lange.

Other photography “heavyweights” who lent assistance to SNCC included Richard Avedon, who helped train a number of SNCC photographers in his studio. He also convinced Marty Forscher, the owner of a famous camera shop in NYC, to donate film and more than seventy-five cameras to SNCC over a three-year period.28

As photographers spread out across Mississippi and the southeast, darkrooms were built in Tougaloo, Mississippi, and Selma, Alabama. Photographers became active participants in the movement. According to Leigh Raiford, “Almost all served in the field on voter registration, literacy training or direct action programs, visually documenting the people they worked with and the events, demonstrations, and projects they helped organize.”29

Some of the images produced that summer included one by Matt Herron that documents a freedom school in Mileston—one of forty-one schools that were established that summer in Mississippi and were attended by more than 2,000 students.30 Other images depict door-to-door canvassing. During the course of the summer 1,600 African Americans were successfully registered to vote out of the approximately 17,000 who attempted to do so.31 But the numbers are misleading. Long-term gains ultimately eclipsed short-term loses. A flood of media attention focused upon Mississippi when Schwerner, Goodman, and Chaney went missing. During the Summer Project, the SNCC Jackson office received two to three visits or calls per day from the AP, UPI, NBC, ABC, and CBS, along with extensive reports in the New York Times and the Washington Post, among others.32 As a result of the media rush and the organizing campaign, the stranglehold that whites had over state and local politics began to crumble in the years that followed as more and more African Americans registered to vote and black candidates were elected into public office.

Following the Summer Project, SNCC would undergo a sea change. A weeklong SNCC staff meeting in Waveland, Mississippi, in November ended with eighty-five new members—mostly white, northern college students who had been with the organization for less than six months—being added to the staff. This decision ruptured the racial and class composition of the group and led to future tensions that would tear the organization apart.33 Lyon left after the Summer Project. The SNCC that would emerge would become almost unrecognizable to him, and many others. In December 1966, Stokely Carmichael replaced John Lewis as SNCC’s chairman. Nonviolence became a thing of the past. SNCC now stood for black power and the right to self-defense.34 By 1969, SNCC fell apart, for all intents and purposes, but their legacy and many accomplishments remain intact. From an art perspective, SNCC stands as one of the rare examples of a social justice organization that placed a premium on artists as key contributors within a movement. SNCC understood how images worked, and how they should be disseminated. While most organizations let outsiders from the mainstream press cover their struggles, SNCC knew better. It created staff positions for photographers—a decision that aided the movement and enriched the lives of the artists who joined their ranks. In a letter to his parents in February 1964, Danny Lyon wrote, “The Danville pamphlet, a poster that makes money for SNCC, even selling pictures and passing the check on to SNCC; these things have, for a brief moment given me a satisfaction previously unknown to me.”35