Protesting the Museum-Industrial Complex

ART IS NEVER NEUTRAL. Neither are art museums. On October 31, 1969, Jon Hendricks and Jean Toche of the Guerrilla Art Action Group (GAAG) entered the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and went up to the third floor, where Kazimir Malevich’s painting Suprematist Composition: White on White was on display.1 When the guard turned his back, Hendricks and Toche carefully removed the famous painting, rested it up against the wall, and attached a signed manifesto in its place. The text read, in part:

We demand that the Museum of Modern Art decentralize its power structure to a point of communalization. Art, to have any relevance at all today, must be taken out of the hands of an elite and returned to the people. The art establishment as it is used today is a classical form of repression. Not only does it repress the artist, but it is used:

1.) to manipulate the artists themselves, their work, and what they say for the benefit of an elite working together with the military/business complex.

2.) to force people to accept more easily—or distract them from—the repression by the military/business complex by giving it a better image.

3.) as propaganda for capitalism and imperialism all over the world. It is no longer a time for artists to sit as puppets or “chosen representatives of” at the feet of an art elite, but rather it is the time for a true communalization where anyone, regardless of condition or race, can become involved in the actual policy-making and control of the museum.2

The manifesto closed by stating:

We demand that the Museum of Modern Art be closed until the end of the war in Vietnam. There is no justification for the enjoyment of art while we are involved in the mass murder of people. Today the museum serves not so much as an enlightening educational experience, as it does a diversion from the realities of war and social crisis. It can only be meaningful if the pleasures of art are denied instead of reveled in. We believe that art itself is a moral commitment to the development of the human race and a negation of the repressive social reality. This does not mean that art should cease to exist or to be produced—especially in serious times of crisis when art can become a strong witness and form of protest—only the sanctification of art should cease during these times.3

Seconds after the painting had been removed from the wall a plainclothes museum guard ran up to the two artists, ripped the manifesto off the wall, and instructed Hendricks and Toche to leave the room for further questioning. They refused. Instead, they calmly explained that they wanted a representative of the museum to meet with them and receive their demands. More guards arrived and asked the artists for their names, addresses, and phone numbers. At the same time, Hendricks furnished another copy of the manifesto and held it up for museum patrons to read. Eventually the director of public relations, Elizabeth Shaw, and the director of exhibitions, Wilder Green, arrived on the scene, and Hendricks and Toche explained to them that they had no intention to harm the painting. Instead, they had chosen the once-revolutionary work of art as a symbolic site to present their manifesto. Shaw and Green promised to deliver the document to the Board of Trustees, everyone shook hands, and Hendricks and Toche left the museum.

![]()

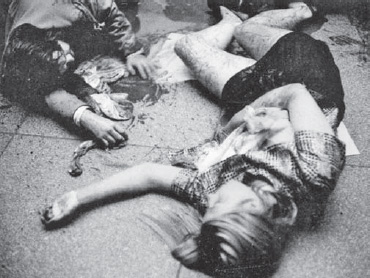

A month later, on November 18, GAAG returned to MoMA, this time accompanied by two other artists, Poppy Johnson and Silvianna. In the midafternoon, the four participants walked to the center of the main lobby. The two men were dressed in suits and ties, and the women were dressed in street clothes. Hidden beneath their clothes were bags of beef blood. Simultaneously the four participants threw 100 copies of their manifesto, “A Call for the Immediate Resignation of All the Rockefellers from the Board of Trustees of the Museum of Modern Art,” onto the ground.

Next they began screaming, slamming into one another, and tearing at one another’s clothes. The bags of blood burst all over them and onto the floor. In short order, a crowd of museum patrons, responding to the disturbance, formed a large circle around GAAG and watched in silence. Screams turned to moans as the four participants sank to their knees and slowly tore at their own clothes in acts of individual anguish. Each participant then laid down in the pool of blood, breathing heavily from the sudden burst of physical exertion.

The action directly referenced the carnage in Vietnam and the violent imagery that was broadcast to millions of Americans via the evening news: a handcuffed Vietcong prisoner executed on a Saigon street, a nine-year-old girl running naked down a village road after being severely burned by a South Vietnamese napalm attack, Buddhist monks setting themselves on fire to protest religious discrimination by the Roman Catholic president Ngô Đình Di

![]() m in South Vietnam. From 1965 to 1975, more than seven million tons of bombs were dropped on Vietnam—twice the total used in World War II. The result of the decade-long war: more than one million civilian casualties, more than 1.1 million dead Vietcong soldiers, and more than 58,000 U.S. soldiers killed in action.

m in South Vietnam. From 1965 to 1975, more than seven million tons of bombs were dropped on Vietnam—twice the total used in World War II. The result of the decade-long war: more than one million civilian casualties, more than 1.1 million dead Vietcong soldiers, and more than 58,000 U.S. soldiers killed in action.

GAAG, A Call for the Immediate Resignation of All the Rockefellers from the Board of Trustees of the Museum of Modern Art, November 18, 1969 (photograph by Hui Ka Kwong, copyright Guerilla Art Action Group)

Thus GAAG’s Bloodbath performance was meant to suggest a literal interpretation of current events. When the four artists stood up, the crowd applauded in unison. An unidentified man, presumably a museum employee, shouted, “Is there a spokesman for this group?” Hendricks responded, “Do you have a copy of our demands?” The man replied. “Yes, but I haven’t read it yet.”4 GAAG then left the museum and shortly thereafter two policemen arrived. The manifesto left by GAAG read, in part:

We as artists feel that there is no moral justification whatsoever for the Museum of Modern Art to exist at all if it must rely solely on the continued acceptance of dirty money. By accepting soiled donations from these wealthy people, the museum is destroying the integrity of art. These people have been in actual control of the museum’s policies since its founding. With this power they have been able to manipulate artists’ ideas; sterilize art of any social protest and indictment of the oppressive forces in society; and therefore render art totally irrelevant to the existing social crisis.5

The text included information that connected the dots between the Board of Trustees and militarism. It noted that David Rockefeller served as the chairman of the board of Chase Manhattan Bank as well as chairman of the Board of Trustees for the Museum of Modern Art. The Rockefellers owned 65 percent of the Standard Oil Corporation, a company that had leased one of its plants to United Technology to manufacture napalm. David and Nelson Rockefeller also owned 20 percent of McDonnell Aircraft Corporation, which was involved in chemical and biological warfare research. GAAG called on artists to boycott MoMA. “If art can only exist through their blood money, then no art. Let’s take art out of their bloody hands,” declared Hendricks. “Let’s not let them use us.”6

![]()

Hendricks and Toche had formed GAAG in 1969, and they remained the core of the group throughout its existence. Toche was born in Belgium and came to the United States in 1965 when he was thirty-three. The FBI described him on March 27, 1974, as a “professional troublemaker, foreign agitator, peacenik, dirty commie, flag-burner, big tall burly bearded hairy man called Toche/Hendricks.”7 Toche, for the sake of clarification, later added that he was a “dissident artist, twice a political prisoner in the USA, human and civil rights activist, and civil liberties worker.”8

GAAG was formed during a critical stage of the protest movement against the Vietnam War. The Tet Offensive of January 1968 had cast doubt on claims that the war would soon be over, much less “won.” Shortly thereafter, CBS Evening News anchor Walter Cronkite told his audience, “The bloody experience of Vietnam is a stalemate” and the war was “unwinnable.” President Johnson remarked to an aide, “If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost Middle America.” In late March, Johnson announced that he would not run for reelection. Later that year, the Democratic National Convention in Chicago would be defined by what took place outside the convention hall: the Chicago police brutally dispersing tens of thousands of antiwar demonstrators. In 1969, the rising number of U.S. casualties, the unpopularity of the draft, and news of the My Lai massacre cemented public opposition against the war. On November 16, 1969, three days after the My Lai story broke, 500,000 people demonstrated in Washington, DC.

GAAG’s activism against the museum took place within this context. They had no desire to march peacefully but chose instead to agitate people in positions of power. On one occasion, GAAG asked MoMA director John Hightower to hold a press conference and pour a gallon of beef blood over his head, slowly repeating the line “I am guilty, I am guilty, I am guilty.” Hightower easily (and unfortunately) dismissed this request, but he could not help but be affected by the interventions that took place within and just outside MoMA’s doors.

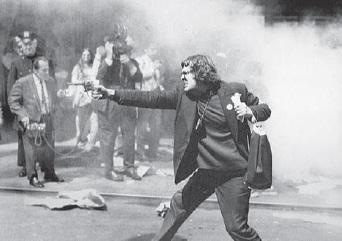

On May 2, 1970, GAAG participated in a staged “battle” outside MoMA that called on the museum to establish a “Martin Luther King Jr.–Pedro Albizu Campos” Study Center for Black and Puerto Rican Art. In typical GAAG fashion, Hendricks and Toche pulled up to MoMA in a rented white Cadillac limousine. Hendricks stepped out wearing a sign that read THE DIRECTOR. Toche wore a sign that read THE TRUSTEE. GAAG then placed a chicken-wire fence in front of one of the doors to protect the museum from the “enemy.” The “enemy” in this case was the large crowd of African American and Puerto Rican artists who had assembled on the sidewalk as part of the protest/performance. Hendricks “The Director” and Toche “The Trustee” began yelling hysterically, “There is no such thing as black and Puerto Rican artists” (an actual quotation from the director of MoMA’s Department of Architecture and Design, Arthur Drexler).9 At one point, Adrian Garcia and Ralph Ortiz rushed the chicken-wire barricade and planted a Puerto Rican independence flag at the barricade. All the while, Hendricks fired a toy gun at the crowd and set off smoke bombs. Toche “The Trustee” was eventually dragged into the crowd, his clothes ripped apart, and then once “dead,” he was thrown into the limousine, along with Hendricks.

GAAG recalled, “At this point, several police cars were already surrounding the area. A policeman peered into the limousine at ‘The Trustee’ crumbled up on the floor and asked: ‘Is he dead?’ As the limousine sped off, ‘The Director’ was able to throw an ignited smoke-bomb into the crowd.”10 Remarkably, GAAG was not arrested for this action. Art had provided the cover—the confused police did not know whether the action was a protest or a sanctioned performance.

Art Workers and Art Strikes

GAAG’s controversial performances shared little in common with the typical solitary studio artist. They related more to the draft resisters and the activists who demonstrated in the streets, occupied college administration buildings, and burned draft records. GAAG asserted that the overwhelming majority of artists and museums were complicit with the dominant system and were thus part of the problem. They asserted that the museum could change if it wanted to; that MoMA—as a nonprofit institution—was in fact a public institution and should represent and listen to the public’s concerns. They also asserted that art could change, that it could become autonomous from the moneyed interests of the art world.

GAAG, Staged “Battle” Outside of MoMA, May 2, 1970 (photograph by Jan van Raay, copyright Jan van Raay)

Other activist art groups in NYC echoed these concerns. The Art Workers’ Coalition (AWC), a group with which GAAG associated, was active from January 1969 to late 1971 and was open to any artist, filmmaker, writer, critic, or arts administrator who wished to join. The anarchic structure and rotating cast of players created myriad projects, but fostered less group identity and cohesion. And unlike GAAG, its three-hundred-plus members were divided between those who had a stake in the art world and those who “wished to tear it down.”11

Artists’ rights and critiquing the power structure of the museum (the Board of Trustees) lay at the heart of the AWC. On January 3, 1969, at 3:45 in the afternoon, Greek artist Vassilaki Takis stunned museum guards at MoMA when he and five of his cohorts walked up to his Tele-Sculpture, clipped the wires, unplugged his work from the wall, and carried it down the hall to the museum’s garden. There, he and his supporters staged a sit-in, demanded to meet with a museum administrator, and were eventually met by Bates Lowry, Director of MoMA. Takis explained that although the museum owned his sculpture, he did not want his work included in that particular exhibit. Takis insisted that the work not be exhibited in the museum without first seeking his consent. Furthermore, he demanded that MoMA host a public hearing on artists’ rights to discuss the strained relationship between artists and the museum. The impromptu meeting ended when Takis received a verbal agreement that his work would not be reinstalled in the show, and that the museum would consider a public hearing.

This action inspired the call to form the AWC. It led to a series of meetings at the Chelsea Hotel, where artists discussed how they could assert their rights and make the art world more accessible to the communities who felt excluded by art institutions. Those who helped form the AWC included Takis, Hans Haacke, Lucy R. Lippard, Carl Andre, Tsai Wen-Ying, Faith Ringgold, Irving Petlin, Dan Graham, and John Perreault, among others.

The name of the group itself was compelling—artists as workers and artists united as a coalition. However, visual artists, unlike theatre artists or professional actors and actresses, were not represented by organized labor in the 1960s.12 Instead, artists worked largely alone and were celebrated for their individuality. The AWC represented an opportunity to break with this model: for individual artists to come together collectively and to agitate for change.

The AWC chose the museum as a site of protest for numerous reasons. The critic and former AWC member Lucy R. Lippard writes, “Artists perceived the museum as a public and therefore potentially accountable institution, the only one the least bit likely to listen to the art community on ethical and political matters.”13 Many artists considered the museum as their own, arguing that without artists, an art museum would cease to exist. Artists also chose museums as a site to demonstrate for many of the same reasons students chose to demonstrate on college campuses: familiarity, ownership, and organizing a natural constituency of potential supporters. As Robert Morris stated in May 1970, “Museums are our campuses.”14

However, artists, as a collective body, did not have easily defined occupations or places of work. Instead they were scattered across hundreds of occupations. They could not shut down an industry the way unionized workers could.15 In fact, much had changed since the 1930s and the examples set forth by organized artists, including the Artists’ Union. The militancy of labor unions and strikes had been curtailed in the late 1930s and 1940s with the Second Red Scare and the Wagner Act that gave workers the right to collective bargaining but impeded their ability to strike.

The Vietnam War helped fuel an upsurge in activism, but the antiwar movement was largely disconnected from organized labor and workers’ issues. Instead, as Roman Petruniak writes, the “AWC were founded upon a more diffuse sense of social angst and frustration.”16 The tipping point was the Vietnam War. “For many of those on the Left, by 1969 the War in Vietnam had eventually come to represent everything that was wrong with America. Analogously, for the art-workers of the AWC, MoMA had come to symbolize everything that was wrong with the art world.”17

One of the first actions by the AWC was to present a list of thirteen demands to MoMA in February 1969 (a list that was later modified to nine demands aimed at all art museums). The original thirteen demands included artist representation on the Board of Trustees, an artists’ curatorial committee, two free evenings a week, the creation of an artists’ registry, artists’ control of the exhibition of their own work, and rental fees given to artists for exhibiting their work. The AWC also called on the museum to become active in advocating for artists’ economic welfare and housing, the creation of an African American and Puerto Rican art section in the museum, and museum programs in African American and Puerto Rican neighborhoods. The modified list of nine demands eventually called for equal gender representation in exhibitions, museum purchases, and selection committees.18

The majority of these demands fell on deaf ears at first, although some ideas were enacted in the years to come in many art museums, including one free day per week and marginal improvements in representing more women artists and artists of color. The AWC, however, was not looking toward changes to occur decades down the road. They were advocating for immediate change during a period of crisis.

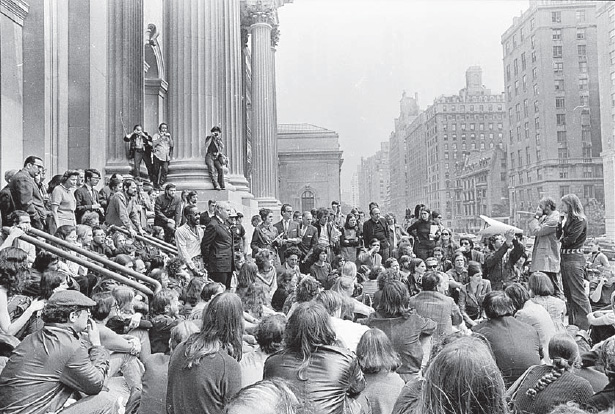

On May 22, 1970, the AWC called an “art strike” in response to the U.S. invasion of Cambodia, as well as the events at Kent State University and Jackson State College, where the National Guard opened fire and killed student demonstrators. Specifically, the AWC called on New York City art museums and galleries to shut their doors for a one-day moratorium in protest of the war.

The Art Strike was inspired by Robert Morris, who had asked the Whitney Museum to shut down his solo show on May 15, several weeks before it was scheduled to close. Julia Bryan-Wilson writes that Morris “declared himself ‘on strike’ against the art system and further demanded that the Whitney close for two weeks to hold meetings for the art community, to address both the war and general dissatisfaction with the art museum as an agent of power. In Morris’s view, ‘A reassessment of the art structure itself seems timely—its values, its policies, its modes of control, its economic presumptions, its hierarchy of existing power and administration.’ ”19

The Whitney refused Morris’s request but relented when he threatened to organize a sit-in at the museum. The following week, the “New York Art Strike Against War, Racism, and Repression” (Art Strike) was launched. Museums that participated included the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Jewish Museum, along with fifty commercial art galleries. Others museums partially closed down. MoMA and the Guggenheim remained open but waived their admission fees. MoMA also screened an antiwar film program and the Guggenheim, in GAAG-like fashion, removed all the paintings from its walls.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, however, refused to close down, and was targeted by the AWC as a result. On the day of the Art Strike, Robert Morris and Poppy Johnson led a demonstration at the Met; protesters crowded onto the front steps, held up signs, and made speeches. Visitors who wished to attend the museum had to “cross the picket line.”

However, the idea of an art strike was ripe with contradictions and symbolic of the marginalized position of the AWC, that in the words of Petruniak remained “vague and unproductive due to the lack of a viable or organized Left.”20 For one, those calling the strike against the Met were not museum employees. If anything, the action was more closely aligned with a consumer boycott, one that prevented the public from consuming art for the day.21 As a targeted boycott, the action served as a litmus test to see which institutions would follow through with the AWC call and which institutions would side with the antiwar cause. Those that did were temporary allies. Those who refused were targeted for protests. Yet the real issue was not the name but the choice in tactics. At best, the Art Strike was symbolic; at worst, the one-day boycott offered these institutions an easy way to show solidarity with the antiwar movement while forestalling substantive change. Yet the demonstration let the Met know that the public was watching and holding it accountable. Moreover, the action mobilized hundreds of artists and directed attention to the issue of artists’ rights and the power structure of the museum and its relationship to war.

New York Art Strike, Metropolitan Museum, May 22, 1970 (photograph by Jan van Raay, copyright Jan van Raay)

Fundamentally, the AWC exposed another key contradiction: they identified as workers, but workers did not necessarily identify with them. Meaning that the largely white, college-educated “art workers” were the ones who were radicalized, not the blue-collar working-class population. The AWC likely identified more with the Old Left—the idea of the 1930s worker who was tied to organized labor (and the CP USA)—instead of the 1960s or 1970s working class that was largely perceived by the Left as being antagonistic to the counterculture and the antiwar movement. This was the same perceived “silent majority” that would later help elect Richard Nixon and later Ronald Reagan.

This gap between the “art workers” and other workers was made clear when the AWC had an antiwar poster printed by the Amalgamated Lithographers Union in NYC. They agreed to print it, but were largely dismissive of the AWC and their cause: protest against the war. If anything, the AWC could relate more to the “workers” at MoMA. They both shared a common interest in art and intellectualism. Thus, the art world became their audience and their target for reform. Lucy R. Lippard stated that the AWC “provided an extremely important consciousness-raising experience for the art world.”22 She adds:

Carl T. Gosset Jr., Construction Workers Protesting an Anti-War Rally at the Subtreasury Building, New York Times, May 9, 1970 (copyright Carl T. Gosset Jr./New York Times)

Before 1969, very few people were aware that artists had any civil rights whatsoever, few knew how the political structure of the art world affected the art, or related art to the politics of real life. Very few people were aware of the economic enmeshment of the arts institutions and trustees in things like wars and military coups and exploitation all over the world—and how these things were reflected in the insidious commodity image of art objects.23

The AWC spurred this public awareness, but they also influenced MoMA employees. In June 1971, MoMA employees formed PASTA (Professional and Staff Association) that organized 112 out of 461 museum employees. Significantly, their internal publication, ORGAN, featured the AWC on the front and back cover of their July 1970 issue, signifying how the AWC had inspired their own efforts to organize. Ironically the “art workers” became the MoMA employees in the fall, when PASTA was formally recognized by MoMA as a labor union.

PASTA union button

Meanwhile, the AWC remained outside the boundaries of organized labor yet crucial in inspiring other workers to organize.24

Q: And Babies? A: And Babies.

Confrontation against the museum was one political tactic of the AWC, another was to collaborate with the museum on antiwar projects. In November 1969, the AWC Poster Committee, a subcommittee of AWC, invited MoMA to co-sponsor the poster Q: And Babies? A: And Babies that addressed U.S. war atrocities in Vietnam, specifically the My Lai massacre. The collaborative approach was significant. Protest posters and graphics from twentieth-century movements in the United States nearly always derived from below—from groups and individuals who are marginalized. In the case of the AWC Poster Committee, a small activist-art group collaborated with a powerful cultural institution that embodied the upper-class art world. Hence, AWC’s tactics was to ask MoMA to forgo its class interests and to place its institutional name and credibility behind the protest movement. In essence, the AWC asked MoMA to join the antiwar movement.

The image that the AWC selected for the poster was a color photograph by Army photographer Ronald L. Haeberle; it showed dozens of Vietnamese women, children, and babies gunned down by U.S. soldiers on a rural dirt road. Superimposed over the photo was text from a Mike Wallace CBS News interview with Pvt. Paul Meadlo, who had participated in the My Lai massacre. When Wallace asked Meadlo if the order was to kill women and babies. His answer was “And babies.”

This harrowing response helped expose an incident that the U.S. military had tried to keep suppressed for more than a year: the day that a U.S. Army platoon under the command of Lt. William Calley entered the village of S

![]() n M

n M

![]() (or My Lai), March 16, 1968, and opened fire on everyone present. Men, women, children, and babies were gathered up, made to stand next to a ditch, and then were shot to death with M16 rifles and M60 machine guns. The U.S. military estimated that the number of Vietnamese killed was between 175 and 500; reports from Vietnamese civilians put the death toll at 567.

(or My Lai), March 16, 1968, and opened fire on everyone present. Men, women, children, and babies were gathered up, made to stand next to a ditch, and then were shot to death with M16 rifles and M60 machine guns. The U.S. military estimated that the number of Vietnamese killed was between 175 and 500; reports from Vietnamese civilians put the death toll at 567.

Haeberle documented the gruesome aftermath with a government-owned camera and turned the black-and-white negatives over to the Army. Yet he also took color photographs with his own camera and film. These images existed outside the Army’s knowledge, and he later released them to the media. On November 12, 1969, journalist Seymour Hersh broke the story of the My Lai massacre to a global audience. Thirty-five newspapers carried the story, and some, including the Plain Dealer (Cleveland), reproduced Haeberle’s images. A week later, on November 20, CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite began its newscast with some of Haeberle’s images from the massacre. Four days later, Mike Wallace’s interview with Pvt. Paul Meadlo appeared on the same network. Additionally, a ten-page spread of Haeberle’s color photos appeared in LIFE magazine.

The effect of the photos on the U.S. public was intense. The public had seen brutal images of the war on the nightly news and in print, but Haeberle’s photographs were different. These images struck a moral chord, triggering profound questions: How could the U.S. Army consider children and babies to be the enemy? How could soldiers shoot babies? How could this action win the “hearts and minds” of the Vietnamese people?

The AWC, recognizing the power of the My Lai images for furthering the antiwar cause, quickly set up a meeting with administrators at MoMA, with the intention to create a poster that could be widely distributed through museum and art networks. Irving Petlin noted, “I feel the museum [MoMA] should issue a vast distribution of a poster so violently outraged at this act [My Lai] that it will place absolutely in print and in public the feeling that this museum—its staff, all the artists which contribute to its greatness—is outraged by the massacre at S

![]() n M

n M

![]() .”25

.”25

On November 25, 1969, the AWC Poster Committee (Irving Petlin, Jon Hendricks, and Frazer Dougherty) sat down with Arthur Drexler (director of the Department of Architecture and Design) and Elizabeth Shaw (director of public relations), along with other members of the museum’s staff.26 By the end of the meeting it was decided that the AWC would design the poster and cover printing costs for 50,000 copies. MoMA would handle shipping costs and would distribute the poster to other museums in the United States and around the world. MoMA would also lend its name to make it easier for the AWC to seek out a printer and gain permission rights for the photograph. The meeting ended, however, without MoMA fully committing to the project.

Artists’ Poster Committee: Irving Petlin, Jon Hendricks, Frazer Dougherty, Q: And Babies?, 1970, offset lithograph (photograph by Ron L. Haeberle, image courtesy of the Center for the Study of Political Graphics)

Nonetheless, the AWC moved forward. Haeberle gave the AWC permission to use his image free of charge, the Amalgamated Lithographers Union in NYC agreed to print the image—reportedly in exchange for a drawing donated by Alexander Calder—and businessman Peter Brandt covered the paper costs.

At the same time Arthur Drexler began to get nervous about associating MoMA’s name with the project. He began to question what his bosses—the Board of Trustees—specifically MoMA’s board chairman and founder of CBS Inc., William S. Paley—would think of the poster. In fact, when Drexler did finally present the image to the board, the project was immediately canned. A follow-up MoMA press release read, in part:

The Museum’s Board and staff are comprised of individuals with diverse points of view who have come together because of their interest in art, and if they are to continue effectively in this role, they must confine themselves to questions related to their immediate subject.27

In short, the board stated that antiwar art was not “art.” Ironically, perhaps, the AWC had made a similar claim, arguing that “The Coalition [AWC] is under no illusion that the poster is art. It is a political poster, a documentary photograph treating an issue that no one, not even the most ivory tower esthetic institution, can ignore.”28

However, the issue at hand was not whether the poster was “art” but the power dynamics within the museum. The AWC had shined a light, much in the same way that GAAG had, on the issue of corporate power—specifically the top-down decision-making process of the Board of Trustees and the control that they wielded over the museum. The statement by the board was a calculated effort to deflect attention away from their own complicity in an unpopular war. They falsely asserted that the board and the museum staff were one and the same and that the duty of a museum was to concern itself with issues of art and aesthetics only. In short, they tried to present the idea that MoMA was neutral on the war, when in fact MoMA, as directed by the Board of Trustees, was anything but. The board at MoMA (much like the boards at the vast majority of elite cultural institutions) was comprised of hyperwealthy individuals who represented some of the most powerful corporate and media entities in the country. If anything, the AWC should have expected the board to turn down their project. Their only misstep was not to inform the 700 to 1,000-plus staff members at MoMA who knew little to nothing about the collaborative project, and would have more than likely supported it and pressured the board to try to allow the curators to carry through with the co-authored project.

Undeterred by the rejection, the AWC went ahead and distributed 50,000 copies of the poster through informal art networks and activist networks. The AWC also issued a press release that chastised the board’s decision, calling it a “bitter confirmation of this institution’s decadence and/or impotence.”29

Unable to collaborate with MoMA, the AWC returned to the familiar role of a marginalized group fighting against a powerful institution. On January 3, 1970, a group from the AWC gathered on the third floor of MoMA in front of Picasso’s famous antiwar painting Guernica and held up copies of the Q: And Babies? A: And Babies poster in front of it.30

Demonstration at the Museum of Modern Art in front of Picasso’s Guernica by a group from the Art Workers’ Coalition protesting the Museum of Modern Art’s reneging on their agreement to co-produce the Artists’ Poster Committee’s poster Q: And Babies?, January 3, 1970 (photograph by Jan van Raay, copyright by Jan van Raay)

They also set four wreaths beneath it. Artist Joyce Kozloff sat in front with her eight-month-old baby, and Father Stephen Garmey, an Episcopalian minister and chaplain at Columbia University, read a memorial service in honor of the victims at My Lai. His service interspersed verses from the Bible with horrific extracts from the My Lai article from LIFE magazine, and closed with a poem by Denise Levertov. As he read, supporters held up copies of the AWC poster in the air. MoMA chose not to have museum guards stop the demonstration. Less than a week later, on January 8, the AWC returned to Guernica and staged a lie-in on the day of a Board of Trustees meeting. The AWC demanded to speak with the board, but were refused. In an interview given forty-plus years after this action, Jean Toche conveyed succinctly the political motives of the AWC, GAAG, and the broader movement that had inspired it: “They [museums] have become essentially a capitalist tool—a tool for entertainment and a tool to augment the financial wealth of the art world. Change them or destroy them.”31